CHAPTER 12

ACCELERATE

After we got hit, the Boss saw me and said, “We gotta talk.” He got in the turret, put his hand on his face and just looked at me for a long time. No words. I broke down, bawling. I wanted to go home. He said, “I’ll send you home, but we’ve got guys here who need you. This is your decision point.” I stayed.

MOTHER

Until writing this book, I had not fully grasped that the need to change the timing, tempo and tenor of Operation Medusa had arisen at one bizarre meeting at the residence of the Governor of Kandahar. A meeting I wasn’t even there for.

Here’s the background. Operation Enduring Freedom began as an American operation but from the outset was structured to make way for an International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) to start taking over operations as early as 2002. The process was designed in slow, measured stages, with the turnover of Regional Command South scheduled for July 31, 2006. During the first half of that year, everyone in Afghanistan knew that command of international forces would shift from the Americans to ISAF. They also knew the Taliban were gearing up to try their luck against the NATO rookies.

In the meantime, Ben Freakley and his brigade commander John Nicholson were going head-to-head with Taliban in Regional Command East, an area slightly smaller than Nova Scotia, and one that U.S. senator Joe Biden had famously dubbed the most dangerous place on earth. Obviously he had never visited RC South.

As the July 31 turnover in RC South approached, Freakley knew he had limited time to use the considerable air and ground assets at his disposal to settle matters in RC East before the Taliban turned their attention to Kandahar.

After that, RC South could have access to all those critical enablers, all those force multipliers, probably somewhere around the end of September or early October. That was the assumption we worked under. It’s why we planned Medusa as more of a staged event, with the kinetic Phase 2 (Strike) not starting until we had all those enablers at our disposal.

SHANE SCHREIBER

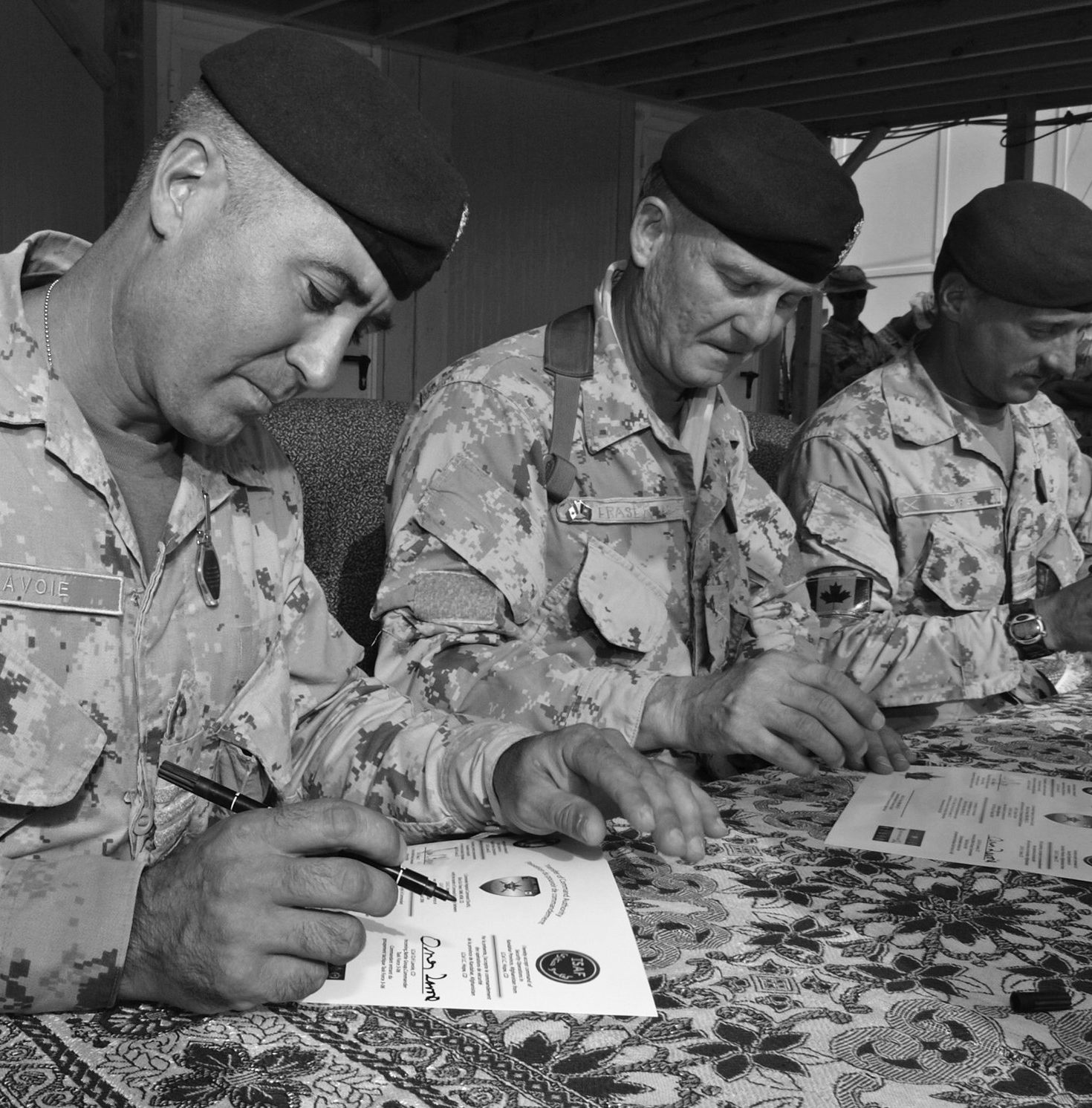

By mid-August, Omer Lavoie’s 1st Battalion, The Royal Canadian Regiment had arrived in Kandahar, and the transfer of command on Saturday, August 19 had Omer take over the Task Force 3-06 battlegroup. Till then that group had been known as Task Force Orion, commanded by Ian Hope and centred around his own 1st Battalion, Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry. Everything was ticking along as planned. Then Governor Asadullah Khalid called a meeting.

Governor Khalid was a rebel and difficult to work with. Early in 2006, we had rated him as effective, but that assessment would change. He always played for his own gain. To shore up his power base, he kept two advisors inside his tent. The first was Mullah Naqib, the tribal elder for Arghandab District who was incredibly influential, having come into notoriety for pushing the Soviets out of his area. In particular he was known for taking out three Russian tanks with his own RPG and then personally executing thirty Russian soldiers, apparently with some relish. His district never had problems with the Taliban, because Mullah Naqib gave them full, free and unquestioned transit through his territory to places like Panjwayi. They could bring all the troops, weapons and munitions they wanted across his turf, and no doubt be well fed and quartered as they did. Governor Khalid relied on Mullah Naqib for many reasons: he had constant access to the Taliban leadership, he was already bent and therefore manipulable, and he would happily lie to anyone.

Ahmed Wali Karzai was his other close confederate. Wali was one of President Hamid Karzai’s three brothers and had served as a key ally to the U.S. military in the south of Afghanistan from the moment they arrived. He too was corrupt and under the active surveillance of other organizations—who, rumour had it, were paying him to get things done when it suited them. An entrepreneur—as much as anyone on the take who double-deals and uses public money to pay off his friends could be dubbed entrepreneurial—Wali Karzai also strong-armed his way into the position of chairman of the Kandahar Provincial Council. He used that position to his advantage from 2005 until his own head of security assassinated him with one pistol shot to the head and one to the chest in July 2011. No one was surprised; it was the ninth assassination attempt against Wali in as many years.

So with Mullah Naqib and Wali Karzai as close advisors and co-conspirators, Governor Asadullah Khalid felt untouchable. But he, like so many, had a weak spot—unquenchable ambition. He wanted as much power as Wali’s now-famous brother Hamid, and to get it he knew he would have to land a plum job in Kabul one day. I knew that about him. Once, when we were at a meeting with Khalid and his retinue listening to a load of political doublespeak that screamed do it our way or else, I’d had enough. Khalid was trying to get us to hire his own police for our security, thereby putting his henchmen where they could watch us and report. He could then pass on our plans to the Taliban. It was a clumsy attempt at infiltration and, as soon as he made the suggestion, I drew him aside for a private word. I don’t recall if I asked everyone to leave the room or just led him down the hall to his own office, but no guards, no police and no interpreters were present. I told him, “Enough of this bullshit, Khalid. You think you’re tough, but I’m Dave Fraser and I’m the biggest, meanest warlord in this part of the country. I’ve got more men, more weapons and more ammunition than you’ll see in your whole miserable life. I know you’re corrupt. But I have friends everywhere. I can stop you from getting any position in Kabul you could ever dream of having. So no more busting NATO’s balls down here. Agreed?”

Governor Asadullah Khalid was a young, ambitious and well-connected politician. He was close to the Karzai family (Hamid Karzai was president of the country at the time) and ran the province out of his pockets. He had numerous cell phones that he would answer any time they rang (even in meetings), and he would often run off because of what he’d been told in the call. When I first met him, it was not uncommon for him to charge out of the office, jump into his SUV and head straight into some firefight with his AK-47. That was simply how he did business. He could speak very good English and had business dealings in the U.S. Khalid was probably a businessman more than he was a politician. He was always working on the margins, which made things more difficult than they should have been; however, he had energy and wanted to get things done. That was important, and we did get a lot done. Khalid was inexperienced, but he was smart enough to learn from the advice he was given by the small circle of tribal advisors he had around him. Only once did I have to intervene and explain to him the way things were going to be. We did this with just him and me, ensuring he never lost face with the team, and after that meeting we worked well together. He was one of those individuals you liked, though you knew that he was somewhat grey and you needed to keep a finger on him. He was the future of the country and he needed to be allowed the time to grow, which he did. But you could never take your eye off him.Credit 23

And he agreed. After that, while we never trusted him, he never gave us any more trouble. In return, we never let him lose face in public. Tit for tat.

On August 17 and 18 I had hunkered down with my assistant chief of operations Shane Schreiber and our planning team to go over our plan for Operation Medusa in detail. We were already in the middle of Phase 1, shaping the battle by playing whack-a-mole. The Taliban were the moles, and our artillery was the mallet. We were still tracking a likely start date for decisive ops some time in mid to late September. While we had been given priority of resources (read air cover) through August (mostly because of the countrywide change from Operation Enduring Freedom to NATO, and local turnovers including the Canadian task force in Kandahar, the British task force in Helmand and the Romanian task force in Zabul)—that was for that month only. Remember, back then we were still thinking that in September, those resources would be swung back to RC East for their own offensive operation against the Taliban. But we knew we had three or four more weeks in the first phase of Medusa to play whack-a-mole with the enemy, collect intelligence, get Omer’s troops in shape, rally the political and tribal leaders, prepare the population and continue detailed planning for the upcoming combat phase.

My plan was to attend the transfer of command authority (TOCA) ceremony on August 19, in which Omer Lavoie and the RCR would relieve Ian Hope and his PPCLI, then shoot up to Kabul to brief Generals Richards and Freakley, the ISAF Regional Assessment Board and the Canadian Advisory Team. That done, I’d head to Ottawa to brief the Minister of National Defence on what we were up to. I’d also have time to brief General Mike Gauthier, Rick Hillier and Prime Minister Harper on the upcoming operation, and then attend two change-of-command ceremonies in Edmonton two days later.

After the TOCA, I jumped on a plane to Bagram and was gone. That afternoon, Ian and Omer came over to the RC South headquarters and met our deputy commander Steve Williams, chief of staff Chris Vernon and Shane Schreiber. At around 1400 hours they received an urgent invitation from Governor Khalid to be in his compound by 1700, so they fired up Ian and Omer’s TAC and convoyed into Kandahar. I’ll let Shane tell the story.

We got there on time. There with the governor was Haji Lala, the chief of one of the local Panjwayi tribes who, our intelligence had confirmed, was a senior Taliban commander. Beside him were other tribal elders including Haji Amitullah, a man we strongly suspected to have Taliban affiliations of his own. Wali Karzai showed up later. It was a weird vibe. People we knew to be traitors were sitting right there smiling at us.

The governor got to the point. He opened by saying, “I understand that you have heard that my friend Haji Amitullah is making a deal with the Taliban.” All of us on the RC South staff expected the governor to now deny that allegation and vouch for his friend. Instead he said, “Friends, I am here to tell you what you have heard is absolutely true.”

Boom.

There was a moment of stunned silence and disbelief. The Governor of Kandahar had just outed Amitullah in our presence, essentially signing this guy’s death warrant. It was a bit of a brain-grenade. He went on: “Some of these other leaders are also speaking to the Taliban.”

Double boom.

“They are talking to the Taliban because the Americans are leaving, and ISAF says it won’t fight because ISAF is here just for rebuilding. So the Taliban are telling the people that they alone have been left to look after security in Kandahar. If that is true, what choice do my friends have but to make deals with the Taliban?”

Omer Lavoie and I had never met before the Afghanistan mission. He joined my brigade during our operational evaluation and shadowed 1 PPCLI. Following that, he was fed our reports from theatre as he prepared his unit to take over from Ian Hope’s task force. When I met Omer again, it was during the handover in theatre and it was one of the busiest transitions we had during our tour. Omer was operationally experienced and passionate about his unit. He had done much to get ready for the mission, but nothing could have prepared him for the tempo that he faced when he arrived. His 1 RCR did not have the opportunity for acclimatizing in theatre like other units. They were put to the test immediately. Omer was ably assisted by one of the best regimental sergeant majors I have seen, Bobby Girouard, as well as his deputy Marty Lipcsey and some good company commanders. 1 RCR, up until then a battle-untested formation, had to learn on the job, so to speak. It took its toll on Omer, who felt the weight of command because of his love for his soldiers. Nevertheless, he did it and the unit was successful—albeit at a terrible cost. Command is a lonely position, and for Omer it was more lonely given that he arrived at the height of the biggest battle we would fight during our tour.Credit 24

Shane Schreiber was my brigade chief of staff when I took over 1 CMBG. He essentially ran the staff and ensured everything was coordinated. Never have I met someone as smart or brilliant as Shane. He was well read, could write like no one else and had a work ethic that was commendable. I was thrilled to have him as my cos. He was well liked by all and was a focal point in the HQ. Shane never showed he was feeling the pressures of the job and was always good working with people, even when they needed a kick. He had a way of getting the most out of everyone. He was my go-to guy. I think if we had not had Shane, our operations would not have been as effective. The operational tempo we had trained for paled in comparison to the real thing, and Shane managed all of this with apparent ease. It was his intellect coupled with his work ethic that made the impossible possible. He did make me laugh many times. During our operational training mission in Wainwright, we had planned a complex brigade operation—“a symphony in five acts.” During the night, someone higher up changed something, trying to make it easier for us, but the reality was that it undid all of our preparations for the next day. At about 0200, Shane told the staff to wake me up because this was going to take my intervention and approval. He sent Darcy Hedon, one of our great officers, to do the honours, reasoning that I wouldn’t growl at being awakened by Darcy, whereas I might if it were Shane. Smart move.Credit 25

Triple boom.

Chris Vernon asked calmly, “What makes you think ISAF won’t fight?”

The governor then alluded to an ISAF information campaign surrounding the recent launch of the Afghan Development Zone concept promoted by General David Richards. He shot back, “That’s precisely what you, ISAF, are telling us. You are here for development and not for fighting. Here…read what you said.”

Quadruple boom.

A vigorous conversation ensued in which both the will and the capability of ISAF to take on the Taliban were more than questioned, they were openly denied. To demonstrate RC South’s commitment, Chris Vernon explained the concept of operations for Medusa, which had already received endorsement from the Afghan government in Kabul and this very governor in Kandahar. ISAF was about to demonstrate its will and capability to defeat the Taliban on the doorstep of his city. We would produce a demonstration of firepower that the people of Kandahar could not help but see. It would be a highly public destruction of the Taliban, just like a showdown at high noon in a Western movie.

That raised an eyebrow or two.

“One concern from ISAF’s perspective,” I pointed out, “is the strong likelihood of collateral damage. RC South and coalition forces have been roundly condemned for the level of such damage inflicted on locals. We’ve been criticized by President Karzai, by you, Governor, and by other officials.” They didn’t know as we did that the damage in question had been inflicted largely by special operations forces and not our brigade. But we knew that taking on the Taliban in a conventional fight would risk significant collateral damage. “I guarantee you,” I said, “that we are going to break your compounds and smash a lot of stuff trying to get at the Taliban, so you’ll have to find a way to not criticize us for taking the measures you’re asking for.”

The governor and many of the other tribal elders in the room nodded their heads. One who had not yet spoken said, “Go ahead and break what you must. We cannot live in our homes. We cannot use our compounds with the Taliban there. It is all useless to us. If you must destroy it to drive out the Taliban, so be it.”

Chris Vernon added, “You must move your people out of harm’s way. No one will be safe from the firepower we’re going to throw at this.” The Afghans looked at each other and came to a quick agreement. “We will get them out of the way. We will bring them to the city or elsewhere to make sure that they are safe.”

To the conventional military mind, warning the public (and therefore the enemy) of an impending attack is an egregious violation of operational security, but we had to do it. We agreed to publicly inform both locals and Taliban that they had two weeks to leave the area. Anyone left in Pashmul or Zhari would thereafter be considered an enemy and be destroyed. To maintain operational security and keep the Taliban guessing, we wouldn’t say exactly when or from which direction we were coming, but by God we were coming.

The meeting went on with some great lines being spoken. Steve Williams, our American deputy commander, gleefully promised Haji Lala that he would walk hand-in-hand with him over “the smashed rubble of Pashmul” as Christina Green, our Canadian CIDA rep at the far end of the room, quietly went pale. Haji turned to me and in a breathless whisper asked, “Did the American just promise to destroy the village to save it?” “Not quite,” I answered. “I think he meant to say that by the time we are done, Pashmul will be safe enough to walk around without any fear of the Taliban. But yes, also a bit damaged.”

We got back to RC South headquarters around 2100. I quickly wrote up a meeting report explaining to ISAF headquarters that this was “ISAF’s last, best chance to demonstrate not just ISAF’s capability, but more importantly its will to defeat the Taliban in the vital province of Kandahar.” I had Chris Vernon review it and then sent it to ISAF HQ around 2300 that night. Through the evening, Chris Vernon and I had also been on the phone to the ISAF chief of staff explaining the extraordinary meeting we’d just come from and impressing on them how Medusa was now more important than ever, not just to Kandahar and RC South, but to NATO as a whole.

SHANE SCHREIBER

I never saw Shane’s report. Our email system was encrypted and secure, so after leaving headquarters at Kandahar Airfield I no longer had access. As a result of that meeting and the subsequent change in ISAF priorities, Operation Medusa’s strike phase would now begin much earlier than originally scheduled—but I didn’t know that until the day Rick Hillier and I were together attending the change-of-command ceremonies in Edmonton. His cell phone rang. He answered, listened quietly, then looked up and passed me the phone.

Twenty seconds later I knew I had to go back.

A key consideration as I returned was whether I would call back the members of the Posse from their leave. They had departed only a few days before, and they all deserved and needed a rest. Their families needed them too. I understood that they would be supremely annoyed with me, but their displeasure would be bearable given what they had already been through. I decided not to interrupt their break.

I was sitting at the kitchen table when my wife, Shelley, said, “Hey, Dave Fraser is on TV!” And there he was, talking about Operation Medusa. I just thought, “That sure as hell better be file footage.” But a banner on the screen read LIVE FROM KANDAHAR. I blew a gasket. I stormed out to the garage, threw a bunch of things around, then after a long time came back in the house very quiet. The Boss was deliberately keeping us out of theatre, and we couldn’t do our job, which was to support and protect him. We were letting him down.

DAVID “BUCK” BUCHANAN

Commanders are busy people, and without a good staff around them they will simply not be able to handle the volume of work that they have to. Working as the executive assistant (EA) to a French general in Sarajevo, I learned that staff are critical in allowing generals to think, lead and provide guidance. If the general is doing more than that, the staff are not doing their jobs. When I arrived in Edmonton to take over the brigade, I had a personal assistant but no EA, which was going to be critical in theatre. I met David Buchanan during our operational evaluation exercise. He ran our ISTAR capabilities and was an artillery officer. I was so impressed with his talents, I made him my EA and said he could do any other tasks as required. It was one of my best decisions. “Buck” was my gatekeeper and managed everything that went in or out of the office. He was the source for anyone who wanted to know what I thought. Buck was a no-nonsense gunner who could manage volumes of detail with ease. He took care of everything, allowing me to think, lead and provide guidance. When Buck spoke, we all listened. He was also diplomatic in working behind the scenes to ensure that I was focused. Buck might not have been the most sociable person to others, but then again, others did not fully appreciate the burden or volume of what went on inside my office. Buck was one of the unsung heroes of this mission.Credit 26

I was in the Maldives with my wife when I turned on BBC and saw the Boss telling the media that Operation Medusa had started. I flipped. I totally flipped. I said, “I need to be there. I’m leaving. I’m getting off this fucking island.” Trina said, “What are you gonna do, swim back?”

BILL “MOTHER” IRVING

In theatre I still had some members of the Posse who had taken their leave earlier. I also had our newest close protection team member Adam Seegmiller and my personal assistant Greg Chan with me. I determined that we could use the team on hand. We would just have to scrounge transportation until the rest of the Posse came back from leave as scheduled. To this day, I am still in the doghouse for not having called everyone back.

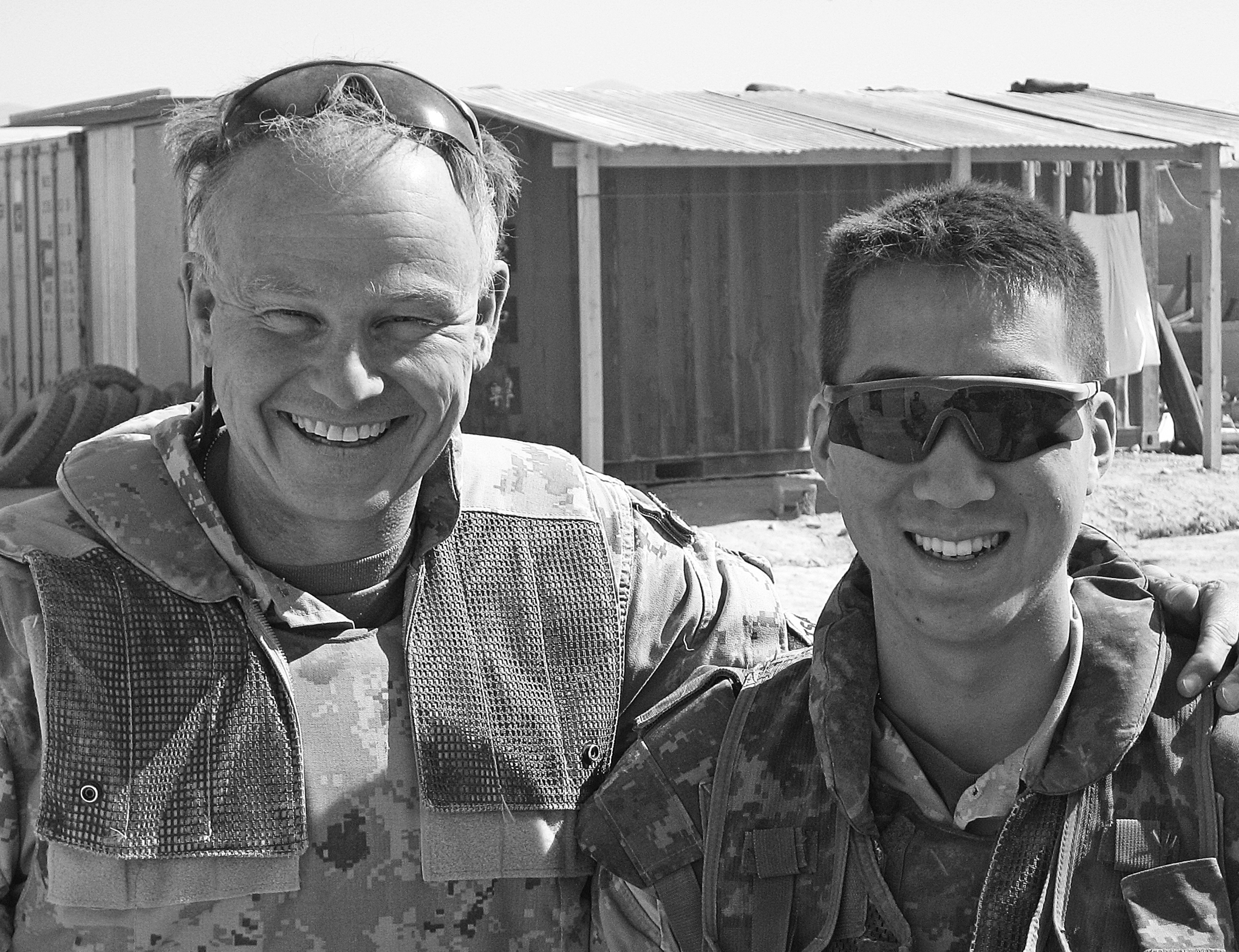

Greg Chan was my personal assistant. A Patricia officer, he joined the Posse just before we launched Operation Medusa after five months in theatre. He proved to be one of the best officers I have ever had the pleasure to work with. He immediately fit into our team, which was a blessing as we were entering the most difficult stage of the mission. When he arrived, much of the Posse were going on a well-deserved period of leave, but then the start date for Medusa was advanced for vital strategic reasons. So at the height of the fighting, it was just Greg who had to manage the office along with everything else that was going on. He understood me completely without my having to say much. He had a great personality, anticipated our needs, coordinated effectively and did an outstanding job. We all benefited from Greg’s sense of humour, which during those days was much needed and appreciated. By the end of Medusa, he was justifiably tired.Credit 27