Whatever works best is what I do. I don’t have any aesthetic thing about one or the other.

Terry Gilliam (Adams 2010)

Terry Gilliam made the transition from illustrator to movie-maker when he made his first animation for We Have Ways of Making You Laugh (1968). With a £400 budget and a two-week deadline, he volunteered to translate the potentially funny but seemingly unusable ‘tapes of terrible punning links between records made by disk jockey Jimmy Young’ into visual language (Marks 2010: 18). Inspired by the technique of avant-garde filmmaker Stan Van Der Beek, Gilliam explains, ‘I could do what I do – cut-outs. So I got pictures of Jimmy Young, cut his head out and drew other bits and pieces and started moving the mouth around’ (Monty Python and McCabe 2005: 113). Gilliam’s ability to make such visual spectacles on the cheap using found material has become one of the director’s trademarks. From his Monty Python’s Flying Circus (1969–74) animations to his live-action films and computer-generated art, he has forged his own distinct aesthetic of cinematically dense, textured worlds that are mundane yet absurd, hallucinogenic yet barren, and bursting with gadgetry and grotesquerie. His rich aesthetic sensibility reflects such influences as German Expressionism, Ray Harryhausen, Hieronymus Bosch, Alfred Hitchcock, Lewis Carroll, Mad magazine, and a Chevrolet assembly line.1 These influences and experiences coalesce in his animation and live-action production design to satirise modern dehumanisation and apocalyptic dystopia via neo-Victorian design, absurdist medievalism, intestinal ducts and anachronistic technologies. By examining his animation and his live-action film, especially his first solo-directed film, Jabberwocky (1977), this chapter traces the ways in which Gilliam’s aesthetic has influenced and incorporated the visual style and movement known as ‘steampunk’, a postmodern aesthetic and rebellious movement mixing Victorian imagery and steam-powered technology.

Gilliam’s aesthetic is immediately recognisable yet difficult to define. Peter Marks underscores the difficulty of categorising the filmmaker at all because of the hybridity that he and his films embody (2010: 2–6). This is partly geographical, for the native Minnesotan has lived in England since the late 1960s. As Marks details, Gilliam’s filmography fits within a range of ‘UK Film Categories’, some of which combine American and British finance and some US productions that incorporate British finance, ‘creative involvement’, or ‘cultural content’ (2010: 45). The director’s films also blend genre categories, such as the ‘previously undemographed medieval comedy market’ with Monty Python and the Holy Grail (1975), which he co-directed with Terry Jones, and Jabberwocky, his solo directorial debut (Marks 2010: 10; McCabe 1999: 63). Gilliam describes his work as ‘reactive’ – an ‘alternative’ to ‘the way the world sees itself, or the way the world is being portrayed’ (Adams 2010). Both reactionary and revolutionary, Gilliam’s approach to filmmaking manifests both the process and aesthetic we now describe as steampunk.

Like Terry Gilliam as filmmaker, steampunk is difficult to define because it is, as Rachel Bowser and Brian Coxall write, ‘part of this, part of that’ (2010: 1). Steampunk’s suffix denotes its status as an artistic movement distinguished by countercultural themes that focus on ‘underground movements, marginalised groups and anti-establishment tendencies’ (Remy 2007). Whereas cyberpunk is concerned with a data-powered world, steampunk focuses on the material and industrial world. By convention, steampunk deploys intertextuality, pastiche, bricolage and anachronism (see Pagliassotti 2009). Gilliam’s aesthetic – and the kind of anarchist, rebel ideology it embodies – both exemplify and inspire the slippery tenets of steampunk, in particular historical anachronism, claustrophobia, pastiche, some ‘invocation of Victorianism’ and machinery: wires, gears, cogs and ducts – lots of ducts (Bowser and Coxall 2010: 1).

Bowser and Coxall explain elsewhere: ‘steampunk is about things – especially technological – and our relationship to things’ (2009). In contrast with the slick contemporary design of surfaces that the consumer can only stroke and tap but not open and/or repair (such as the recent generation of Apple devices), steampunk exposes the innards of things and society by making them visible. Bowser and Coxall identify one defining element of steampunk as ‘the invocation of Victorianism’, for example, stories set in London or ‘in a future world that retains or reverts to the aesthetic hallmarks of the Victorian period … or a text that incorporates anachronistic versions of nineteenth-century technologies’ (2010: 1). Steampunk’s appearance is characterised by the Victorian industrial: ‘dirigibles, steam engines, and difference engines built out of brass rods and cogs, cogs, cogs’ (2010: 16). The cogs are particularly significant because steampunk’s insistence on the visibility of labour makes it more than an aesthetic. Gilliam’s development as an artist coincided with the historical period in which the elements that would become steampunk emerged. Cory Gross describes this moment in history – that is, the My Lai massacre, the Summer of Love, Woodstock, the Stonewall riots, the moon landing, the avant-garde cinema of Stan VanDerBeek and Kenneth Anger – as a time in which ‘the romance of the Victorian Era’ and other ‘threads were fermenting that would, by the late 70s, mark the rebirth and eventual solidification of what would come to be known as Steampunk’ (2008).2

As a movement, steampunk also performs ‘a kind of cultural memory work, wherein our projections of fantasies about the Victorian era meet the tropes and techniques of science fiction, to produce a genre that revels in anachronism while exposing history’s overlapping layers’ (Bowser and Coxall 2010: 1). By interweaving different time periods and by making visible the inner workings of an object or system, steampunk criticises capitalism’s historic ‘lack of mercy’ in its treatment of ‘both the haves and have nots’ (Nevins 2008: 10). In its insistence that we confront labour in visible, material forms, steampunk teaches us ‘to read all that is folded into any particular created thing – that is, learning to connect the source materials to particular cultural, technical and environmental practices, skills, histories and economies of meaning and value’ (Forlini 2010: 73). As Dru Pagliassotti suggests, ‘by recycling and rethinking history’s lost dreams and obsolete technologies within the context of contemporary historical awareness, steampunk is poised to offer the world, with an ironic wink and a shiny brass-and-wood carrying case, a vision of the future that offers cautious hope instead of dystopian despair’ (2009). However, both hope and despair characterise Gilliam’s movies, which embody the optimism of the Victorian period’s exciting possibilities and emerging technologies, as well as the dystopian result of these same technologies: the unspeakable slaughter of World War I. In particular, his narratives that are told from a child’s perspective – Time Bandits (1981), The Adventures of Baron Munchausen (1988) and Tideland (2005) – open up fantastic visions of endless possibilities and reflect his sense that children are as intelligent as adults (if not more so), albeit less experienced: ‘Their minds are just as active – more so, in fact, because they haven’t been limited and defined yet. To them, wonderful things can happen’ (Sterritt and Rhodes 2004: 17). The child’s subjective point of view, however, stands in stark contrast to Gilliam’s adult worlds of hyperconsumerism (Time Bandits), war-mongering (Baron Munchausen) and neglect (Tideland) and serves also to underscore the ‘scathing indictment of modern culture’ that characterises his films and steampunk itself (Jones 2010: 103).

Steampunk as Aesthetic and Process

Gilliam’s aesthetic also evokes the artistic influences listed above, and he has yet to describe his production design as steampunk, per se. Nevertheless, its distinctive look, ideology and themes permeate much of his production design and approach to filmmaking and have done so since before the term ‘steampunk’ was coined in 1987 in a letter written by K. W. Jeter in Locus magazine (see Di Filippo 2010). Bruce Sterling and William Gibson’s The Difference Engine (1990) is credited as the literary progenitor of modern steampunk, and Jules Verne and H. G. Wells are cited as steampunk’s aesthetic inspiration, but, as Paul Di Filippo points out, ‘the ex-Python gets too little credit as an outlier of the steampunk movement’ (ibid.). However, Gilliam’s steampunk vision has inspired a new generation of artists, such as ‘Datamancer’ (Rich Nagy), who credits Brazil as part of the inspiration for his innovative brass and wood laptop computer embellished by shiny gears and an ornate crank power switch (see Frucci 2007).

Yet Gilliamesque steampunk does more than expose labour and celebrate Neo-Victorian craftsmanship. Two of Brazil’s initial working titles, Brazil, or How I Learned to Live With the System SO FAR and 1984½, explicitly invoke, respectively, Stanley Kubrick’s critique of nationalist militarism and George Orwell’s critique of nationalist totalitarianism, thus anticipating what Pagliassotti conceives of as steampunk’s ideology. Pagliassotti argues that its Neo-Victorianism ironically challenges Victorianism’s affection for nationalism and ‘the propagation of cultural imperialism’ by not ‘adopting all of the Bad Old Ideas of Victorianism … not its sexism, racism, classism, poverty and other ills’ (2009). Similar to the Victorian images that populate Gilliam’s early animation for Monty Python’s Flying Circus, the Pythons play a squad of Tommies in Monty Python’s Meaning of Life (1983) in ‘Part III, Fighting Each Other’ and give Captain Biggs (Terry Jones) several timepieces, including an ornate Victorian clock, for his birthday.

The delicate craftsmanship of the glass-encased clock with exposed ornate gears and its absurd appearance in a desolate, muddy trench highlight its contrast with the senseless and brutal war machine of World War I, particularly when Blackitt (Eric Idle) takes a bullet in the chest before the rest of the troops are killed, one by one. This satire of oppressive totalitarianism that treats humans as utilitarian automatons frequently appears in Gilliam’s production design, from his medieval tales to his science fiction and opera, via motifs of Neo-Victorian gears and dials fused with cogs, clock faces, keyboards and the ubiquitous ducts.

Such an industrial leitmotif characterises the interrogation room in Twelve Monkeys (1995) where scientists in the future evaluate Cole (Bruce Willis) as a ‘volunteer’ for time travel. In the introductory scene, after Cole’s visit to the desolate winterscape above the underground shelter, figures in elaborate rubber suits and protective masks scrub him with mops and hoses from a distance. Clean and naked, he draws blood from his own arm with a Victorian syringe in an exam room observatory populated by machines composed of exposed sprockets and automated pistons. Next, guards lead him into the interrogation room while an announcer’s voice informs over a loudspeaker, ‘there will be socialization classes in 0700’. One guard declares him ‘clear from quarantine’, and another scans the barcode on Cole’s neck. At his captors’ direction, Cole lets himself be mechanically restrained in a chair that lifts him into the air so that the scientists can communicate with him at a remove, broadcasting their faces and conversation through multiple small screens and speakers that adorn a brass-covered globe. The flywheels, dials and other guts of the scientists’ computers are exposed in a series of glass-topped tables, onto which clutter brass instruments, a variety of clocks and multiple gauges.

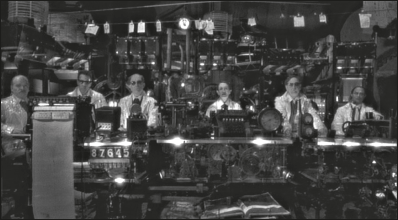

Celebrating the Captain’s birthday in the trenches in Monty Python’s Meaning of Life

Dystopian steampunk in Twelve Monkeys

The industrialised complex of exploitation via Neo-Victorian mechanics imprisons Cole in a dystopian future run by a totalitarian regime of ‘rational’ scientists. Gilliam’s production design particularly embodies steampunk’s ‘harsh view of reality’, in which, as Bruce Sterling has observed, ‘anything that can be done to a rat can be done to a human being. And we can do most anything to rats’ (Remy 2007). In Twelve Monkeys’ future, the scientists experiment on people with dehumanising technology that is also faulty, such as when Cole and a fellow traveler are sent into the trenches of World War I.

The scientists’ dependence on scavenging together a working laboratory out of whatever materials can be salvaged and recycled after the virus devastates the global population has less dystopian roots in Gilliam’s creative process, which principally engages steampunk’s deployment of bricolage. His meshing of outdated and updated technological fashions both anticipates and reinforces steampunk’s focus on historical anachronism. As a cartoonist for Help! magazine (1960–65), which was created by Mad magazine founding editor Harvey Kurtzman, Gilliam became skilled in creating ‘fumetti – photo comic strips that essentially played like a movie storyboard with characters speaking in word bubbles, with Gilliam often writing, casting, and photographing them himself ’ with a ‘16mm Bolex camera and a tape recorder (McCabe 1999: 16, 18).3 As Gilliam remembers, ‘We were always stealing film from trash cans and drawing on it. We’d animate right on the clear film’ (McCabe 1999: 18). When he began working as an animator in London on the children’s television show Do Not Adjust Your Set (1967–69, with Michael Palin, Eric Idle and Terry Jones) and on We Have Ways of Making You Laugh (1968), he honed this approach to his innovative ‘cutanimation’ that flourished on Monty Python’s Flying Circus. To create his cut-outs, he spent time at the British Museum looking for free materials from ‘a lot of dead painters and a lot of dead engravers’ to draw and cut into moveable parts that he would place in a setting and photograph two frames at a time, making the filmmaker, in his own words, the ‘premier cut-out animator of the era’ (McCabe 1999: 24; Gilliam 2006).

The opening credit sequence of the first episode of Monty Python’s Flying Circus revels in the anachronisms created through Gilliam’s bricolage process. As Bowser and Croxall observe, ‘anachronism is not anomalous but becomes the norm’ in steampunk (2010: 3). Marks writes that Agnolo Bronzino’s Venus, Cupid, Folly, and Time (circa 1545) provides the giant foot that crushes many an unsuspecting angry old man, television set, or ‘fat balding gent’ (2010: 22). In Gilliam’s animations, this motif reverses the deus ex machina of the Renaissance, creating machinery out of God. Philippe de Champaign’s Cardinal de Richelieu (1633–40) lasciviously pursues a woman lying naked on a steam-powered train. Rembrandt’s allegorical painting of his wife as the Roman goddess of Spring (1635) hides her face before cherubs from Nicolas Poussin’s Adoration of the Shepherds (1633–34) frolic overhead. In turn, the cherubs bat around a disembodied head until, like a fighter jet, one dive-bombs Richelieu and a cartoon figure inflating the black and white photographed head of a man from a nineteenth-century portrait. Sixteenth- and seventeenth-century images romp with the characters from Edison’s early film The Kiss (1896) and other such ‘photographs, airbrushed figures and images that might have been taken from Victorian magazines or posters’ (ibid.). The pastiche of fine art and grotesque created via bricolage defines one element of Gilliam’s aesthetic and creates a ‘cultivated but irreverent stream of consciousness, one that is witty, risqué and subversive’ and an introduction to the ‘world that would become known as “pythonesque”’ (Marks 2010: 23). Yet it is the Gilliamesque ‘watcherly’ world, pace Roland Barthes (1975), of Eisensteinian montage that exposes its own mechanical workings even as it demands that the viewers translate the meaning of the juxtaposition of images.

Gilliam’s animation relishes embellishments of Victorian imagery and the proliferation of tubes in steampunk as process and aesthetic. In the introduction to Monty Python’s Flying Circus: Terry Gilliam’s Personal Best DVD (2006), which features many of his most popular animations for the television series, the director tells the viewer that he is trapped in a dungeon to protect the ‘truth’ about the comedy troupe. In his tongue-in-cheek revisionist history, he explains, ‘In the sixties … before South Park [1997–]’, the BBC had approached this ‘world-famous’ cartoonist to make his own ‘glorious’ all-animated show. This project, however, was destroyed by the introduction of live-action sketches developed by ‘some college boys that I found rather down on their luck in Piccadilly Circus selling their well-educated bodies for drugs’. When the implied viewer flips a switch, an explosion transforms Gilliam into a cut-animation version of himself in a steampunked basement studio. As the filmmaker cut-out bounces around the room in wide-eyed panic, two television monitors stacked together play a Monty Python skit and an excerpt of Gilliam’s animation. The studio is powered by the amputated hand of God from Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel, shooting electricity into a cog hooked to the editing board, a machina ex deo. Large ducts curve from the foreground and stretch across the ceiling, one supporting a radioactive warning-sign over a doorway that emits a glowing green light. The Gilliam cut-out cartwheels away as a spotlight searches the room from above. He cowers as a robot disguised as a camera lowers into the room and seizes the animated artist, squeezing him into blood spatter before curtains fall triumphantly on the grisly scene. The gleeful moment of violence in which creation destroys its creator is emblematic both of the dystopian themes that Gilliam’s filmography explores and of the steampunk aesthetic that influences (and is considerably influenced by) his work (see Di Filippo 2010).

The aesthetic elements at work in his Personal Best introduction cultivate explicit steampunk animation. In one featured introductory credit sequence, the roses that blossom into the series’ title reveal, as the camera tracks back, that they grow from the bald head of a man who is submerged in what appears to be a puddle of urine. Bronzino’s giant foot stomps on this bizarre image, and then the scene cuts to a factory that mockingly anticipates the dehumanizing mechanical systems of entrapment seen in both Brazil and Twelve Monkeys. Surrounded by an ornate system of pulleys, prongs, flywheels and cylinders, a tripod raises a short, mustachioed man into the centre of the frame. An amputated hand hanging from pistons reaches to pluck his head from his neck, then another piston on the right side of the frame shoots out and punches his torso from his body before a third piston attached to an amputated foot kicks a torso onto his legs.

When the manufacture of the Frankensteinian creature is complete, the head is reattached to the feathered torso, and a leg emerges from the piston, kicking it from the tripod stool. The figure tumbles onto a conveyer belt emerging from a coiled duct. In the background, cogs and gears continue to grind, and the hand, now holding a box, collects the hybrid man-chicken from the belt and sets him into another frame with an indistinguishable landscape. A cut-out of a grinning male face wearing Victorian-era glasses initiates more odd events, which result in the chicken man hatching from the egg before flying a Monty Python Flying Circus banner across the sky. These factory images comically evoke the grim, inhuman hypercapitalist nightmare of Fritz Lang’s German Expressionist masterpiece, Metropolis (1925), especially its introductory scene, which portrays human workers as mechanical parts that manufacture the urban industrialisation and traps them in an unending capitalist system dependent on cruel exploitation of labour.

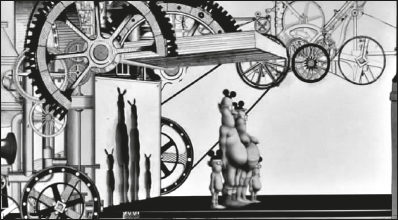

The pastiche creature absurdly undergoes creation and re-creation for mass production that recalls Orwell’s Fordist themes as well as Gilliam’s early job on a Chevrolet assembly line, which he describes as his ‘ultimate nightmare’ (Christie & Gilliam 2000: 19). This Gilliamesque steampunk factory also appears in the introductory sequence of The Meaning of Life, this time mass-producing identical versions of pudgy families adorned in Mickey Mouse ears from a richly-detailed system of gears, cogs and pulleys.

Such a critique embodies steampunk’s anti-establishment tendencies as well as Gilliam’s own distaste for Disneyland, which originated when the amusement park conglomerate, suspicious of his long hair, refused to let him enter. While at the park to review new rides for LA Magazine, he ‘noticed the barbed wire along the top of the fence – Disneyland had become a kind of concentration camp. Truth, justice, and the American/Disney way were getting confused’ (McCabe 1999: 31). Jason B. Jones argues that such an indictment of modern culture ‘is one of the pleasures of steampunk … and that indictment somehow becomes simultaneously both more damning and more acceptable by being voiced from the [mechanical] moment of that culture’s birth’ (2010: 103). Eric Idle’s song lyrics about humans being ‘self-replicating coils of DNA’ play over these images, further augmenting this animation’s industrial anticipation of steampunk.

German Expressionist labour in Monty Python’s Meaning of Life

Gilliamesque steampunk synthesises the economising practice of reusing found material with a critique of exploitative economic policies, which he develops thematically in Jabberwocky and Brazil, although this concept also appears elsewhere in his films. When the Pythons made Monty Python’s Holy Grail, his idea to use coconut shells to mimic horses clopping solved the financial problem of horses being too expensive to employ for the knights. The Crimson Permanent Assurance (1983), a short live-action mini-movie Gilliam created for The Meaning of Life, also predicates its critique of Reagan/Thatcher economic policies on bricolage. It opens in the ‘bleak days of 1983’ when insurance agents who struggle ‘under the yoke of their oppressive new [American] corporate management’ transform their Victorian building into a pirate ship that sails ‘the wide accountancy’ to fight The Very Big Corporation of America. The ageing agents-cum-pirates battle their oppressive executive leadership with fan blades that become swords, create daggers out of stamps and letter holders, and trim sails made of Acme Construction cloths hanging from construction scaffolding. A similar collaboration that combines Gilliam’s thrift with contemporary social satire also created the computers that automate bureaucratic kidnapping and torture in Brazil in an organic moment of bricolage. George Gibbs, the production effects supervisor, found cheap teletype machines, which motivated Gilliam to remove the housing and replace it with ‘the smallest screen we could find: it was like sculpture. Pretty much the whole film was done that way. And you end up with a look that you could never design because you can’t think of it’ (McCabe 1999: 118). That Gilliam practices such thrift to create props, which manufacture a totalitarian system that automates the torture of citizens without due process, engages the irony implicit in steampunk’s bricolage.

Intertextually conjoining the archaic with the contemporary, Gilliamesque steampunk crams frames with anachronistic, ornate structures that expose human exploitation in industrial systems of economic and nationalist domination. In one Flying Circus animated sequence, World War I-era Tommy hats converge as a fleet of flying saucers that travel past a monk who has paused from chanting Latin for lunch and then past a British officer whose duct-like neck snakes from his collar. The hat-saucers spawn World War I British soldiers into a waiting trench, raising the spectre of the Great War while Gilliam was avoiding being sent to the war in Vietnam (a war he opposed). Decades later, these cut-outs culminate in filmic and live-action expression in Gilliam’s 2011 production of The Damnation of Faust. Cinematic footage of soldiers projects over the titular character in the depths of his despair before Mephistopheles leads him to serve in a makeshift army field hospital. In the opera’s overlapping of media, the lightness of Pythonic humor takes on the darkness of the rise of fascism amidst Berlioz’s lyrics from 1846. In The Damnation of Faust Gilliam’s German Expressionist influences saturate his darkly satiric and tragic pastiche of the Holocaust, yet the production – glorying in the merging of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries – somehow retains the spark of humour so pervasive in his early Monty Python animations and his computer-generated imagery in The Imaginarium of Doctor Parnassus (2009).

In another introductory sequence from Monty Python’s Flying Circus, Bronzino’s foot hops by a tiny house, its ankle propping up a woman in Victorian dress. The British Pythons emerge from the house and slide into a black hole that becomes a human oesophagus, landing in the stomach and gurgling through the intestinal plumbing, depicted as interlocking pipes set in motion by a series of pistons, before a primate burps them out of the system. These industrial signatures of Gilliam’s style reflect his fascination with ‘the innards of everything, whether it’s people or machines. The inner workings of things have always intrigued me … I’m curious about how things work, how the guts of a system function, and the sound of plumbing is always comic’ (McCabe 1999: 36). This plumbing fascination is also reflected in a moment of Monty Python’s Meaning of Life’s introduction when a fat, TV-watching man dissolves into a liquid that seeps into a drain and enters the steampunk Disney family-producing factory described above. Its imagery not only bears Gilliam’s aesthetic fingerprint of anachronism but also serves the intent to make labour visible shared by both steampunk and the auteur. The production design bursting with ducts in Brazil, he says, ‘was a result of looking at beautiful Regency houses, Nash terrace houses, where, smashing through the cornices, is the wastepipe from the loo’ (McCabe 1999: 141). This is but one visible manifestation of his conception of time: ‘all these times exist right now and people don’t notice them. They’re all there’ (ibid.). Time, for Gilliam, is not anachronistic but synchronic, making industrialisation and imperialism trans-historical.

While promoting Brazil in Chicago, Gilliam responded to questions about the ducts by pointing out the typical invisibility of the labour that produces the energy and materials we often unthinkingly consume: ‘“Well, don’t you realize what’s behind the walls and the suspended ceiling and under the floor in this room we’re sitting in?” It seemed these kids had no idea of the connections needed for all these things, and of the price to pay. I said there was this balance I was dealing with – what is the price? – and they were stunned by that’ (Christie & Gilliam 2000: 130–1). Similar to the black clouds of pollutants that trail behind contraptions in Gilliam’s collaboration with his long-time creative partner Tim Ollive, the explicitly steampunk trailer for 1884: Yesterday’s Future,4 and Gilliam’s Metropolis-like renditions of factories, the retrofitted ducts expose the guts of society and the labour and price of privilege, both Victorian and contemporary.5 As the director explains, the initial idea for Brazil emerged when he was doing research on the Renaissance period and came across a text from the 1600s at the apex of the witch-hunts: ‘This was a chart of the costs of the different tortures and you had to pay for those inflicted on you; if you were found guilty and sentenced to death, you had to pay for every bundle of faggots that burned you. I started thinking about the guy who was a clerk in the court and had to be present while the tortures were going on, to take down testimonies’ (Christie & Gilliam 2000: 130). The use of anachronism to highlight contemporary social issues via centuries-old imagery is one of the director’s aesthetic and thematic trademarks, for, as he says, ‘constantly shifting perception is really important to me’ (Wardle 1996).

Frequently, such perceptual shifts and anachronistic juxtaposition, such as the Vulcan’s factory in The Adventures of Baron Munchausen building ‘intercontinental ballistic missiles’, as Marks explains, serve both a steampunk agenda and ‘a satirical purpose’ (2010: 119). The single scene that Gilliam directed in Monty Python’s Life of Brian (1979) features the sudden appearance of a spaceship, which abducts Brian (Graham Chapman) and engages in intergalactic warfare before crashing back into Jerusalem. The scene playfully interweaves one mythology into another, though without discrediting the need for mythology and fantasy.6 Rather, it reflects Gilliam’s fascination with the medieval worldview ‘where reality and fantasy were so blended’ (Gilliam 1999). This sequence, with its invocation of alternative history, is also characteristic of steampunk pastiche. The movie’s tale of Brian (a marginalised figure who ends up crucified with several other outcasts after he is heralded as a prophet along with Jesus Christ) is reminiscent of what Mike Perschon describes as steampunk’s ‘post-colonial anti-Empire sentiment’ (2009), which informs Monty Python’s satire of the Roman Empire in particular and of empire in general.

The Steampunking of Lewis Carroll: From Pythonesque to Gilliamesque

Though seemingly anachronistic, this last section analyses the ways in which the director’s aesthetic and approach to filmmaking has always already been steampunk by comparing his first solo project with the trailer for 1884. For his first almost completely live-action movie, Gilliam brought the nightmarish creature from Lewis Carroll’s nonsense poem ‘Jabberwocky’ (1872) to life to explore what the director characterises as ‘the idea of a world where the terror created by a monster is good for business’ through ‘a collision of fairy tales’.7 Though three Pythons appear in the cast, as Michael Palin notes in the DVD commentary, the movie is a significant departure from a Monty Python comedy, in part, because ‘the entire British comedy establishment is in this film’ (Gilliam and Palin 2001). Jabberwocky follows the tale of Dennis Cooper (Palin), who dreams of taking stock and marrying the scornful girl next door, Griselda Fishfinger (Annette Badland). With his aspirations of mediocrity, remarks Gilliam, Dennis anticipates Brazil’s ‘clerk-bureaucrat’ Sam Lowry (Jonathan Pryce): ‘his father is a craftsman, a barrel-maker, but Dennis is more interested in accounting. He’s like a guy somewhere in the Midwest who aspires to own a used car lot’ (Christie & Gilliam 2000: 66). After his disappointed father (Paul Curran) disowns him from his deathbed in a scene resembling Caravaggio’s chiaroscuro in The Death of the Virgin (1605–6), Dennis strikes out to ‘make good’ in the city and return to marry Griselda. Instead, through a series of misadventures, this counter-epic hero winds up accidentally killing the Jabberwocky that terrorises the Kingdom of Bruno the Questionable (Max Wall), thus earning him the fairy tale ending that, says Gilliam, ‘we’re all told we want’, but that he does not seek: one-half of the kingdom and the hand of the Princess [Deborah Fallender]’ (McCabe 1999: 70). Though only one scene bears the steampunk aesthetic, the director’s filmmaking philosophy and process bear steampunk’s anarchist ideology.

While the film was not well received by reviewers expecting a Monty Python movie or viewers disappointed by the scatological and bloodily violent realism of Gilliam’s anti-heroic fairy tale world, New York Times critic Vincent Canby described it favourably, noting its use of pastiche as ‘a wickedly literate spoof of everything from Jaws through Ivanhoe to The Faerie Queen’ (1977). Canby noticed its mock epic aim and lauded Jabberwocky as ‘a comedy with more blood and gore than Sam Peckinpah would dare use to dramatize the decline and fall of the entire West. The world through which Dennis stumbles ever upward is an unending landscape of misery, torture, filth, slop buckets, sudden death, and all-round decay … showing us the past as it supposedly really was’ (ibid.). Gilliam’s medieval pastiche combines the grim and grimy realism of a crumbling castle and the medieval sewer system with the grotesquely beautiful canvases of Peiter Bruegel and Hieronymus Bosch. The dust that coats King Bruno and his helpmate Passelewe (John Le Mesurier) – and that cleaners futilely and endlessly attempt to sweep – composes the failing architecture that Gilliam characterises in his commentary as symptomatic of ‘the whole regime’. He uses actual paintings as ‘historical shorthand’, creating a canvas montage on which the camera tracks to reveal pertinent details, while the narrator explains the story and then reconfigures the visual elements in the paintings into the mise-en-scène.8 The movie is a visually stunning work of art that comically confronts the viewer with the filth and excrement of both the human system and a bureaucratic system of commerce based on members-only employment and dependent upon fear to subjugate citizens to that system.

Satirising that system in Jabberwocky’s city market, a man sells fast-food rats on a stick, and merchants whip human beasts of burden to speed them through rush hour to meet with King Bruno. As Marks explains,

A key target of this satire are the merchants who first appear on their way to see Bruno, riding in sedan chairs that correspond to modern limousines. Held aloft by their bearers, they discuss market fluctuations and economic predictions. But underlying antagonisms and competitiveness force them to ‘accelerate’ their sedan chairs in a ludicrous race that mercilessly exploits their bearers while exposing their mutual hatreds and fundamental duplicity. Under-cranking the film briefly at this point recreates the frenetic pace of a silent movie car chase. (2010: 51)

Steampunk ‘oil change’ for Jabberwocky’s knights

Gilliam subtly emphasises this satire of economic exploitation in King Bruno’s castle, in which he foregrounds servants working. They sweep and clean the dust constantly falling from the royal interiors while merchants beg the king to stop the tournament of knights jousting for the privilege of fighting the monster, an argument the bishop supports since the monster keeps church attendance at record highs.

Gilliam’s DVD commentary typically reveals the intricate labour behind every scene. For Jabberwocky, he explains that he hated Rock Hudson’s perfect teeth in the 1950s, so the characters’ blackened ones offered ‘the most anti-American statement I could make’ (Gilliam and Palin 2001). The director’s long-running resistance to the US military empire, then so recently embroiled in the quagmire of Vietnam, as well as his appreciation and practice of creative craftsmanship over mediocre repetition, emerge in Jabberwocky’s script and illustrate steampunk’s rebellious, anarchic ideology. Gross argues that steampunk’s ideology ‘mythologizes the self-reliant, DIY [Do-It-Yourself] tinkerer or artist’, which describes Gilliam’s bricolage on Jabberwocky. In the DVD commentary, Gilliam expresses frustration with the wires being visible in the joust scenes, but such mechanical slippages in special effects actually exemplify steampunk’s aesthetic, slippages that would re-appear in the staging of his 2011 opera, reminding the audience of the machinery required to create the live-action magic. As he explains in the commentary, the film’s shoestring budget frequently allowed only one take, producing such accidental anachronisms as a truck in the background of a battle scene. But his movie-making and live-action labour proves often consciously, and even anarchically, steampunk.

To create the medieval set that would inspire John Boorman to order his crew on Excalibur (1981) to watch the film fourteen times, Gilliam and his staff recycled sets from both Oliver! (Carol Reed, 1968) and The Marriage of Figaro (Jean-Pierre Ponnelle, 1976) (see Gilliam and Palin 2001). Moreover, while Blake Edwards was making one of the Pink Panther movies, Gilliam would ‘borrow’ from the castle set: ‘We were guerilla film-makers out there, stealing and scavenging what we could’ (Christie & Gilliam 2000: 67). In the penultimate scene when Dennis accidentally vanquishes the monster, Gilliam literally recycles found objects by burning tyres for smoke effects and draping actual animal carcasses around the quarry, all of which Palin describes as going ‘beyond the rules of filmmaking’ (Gilliam and Palin 2001). In a simultaneously post-apocalyptic/meta-industrial revolution process, while filming Jabberwocky, Gilliam developed a bricolage strategy still in use on his sets. He would have the crew ‘assemble a kit of bits and pieces that we could carry around with us everywhere so that we could always get a shot: things like a piece of foreground, the edge of a building, a little Lego kit of parts’, which he would film at different angles to make them look different (Christie & Gilliam 2000: 79). Essentially his cogs of movie production, this kit made possible his chiaroscuro mise-en-scène, particularly when he would use black velvet drapes instead of building higher sets to achieve lighting.

Because the production was running out of money when the factory scene was shot, the crew played extras and reused pieces of sets from other scenes in the armourer’s workshop. Thus the flagellates’ wheel becomes a gear in the scene, anticipating steampunk’s aesthetic. Pulleys hoist knights like cars so mechanics can work on their armour and give them ‘oil changes’ from underneath. Humans move in automated rhythms, pump air to power the steam, grind on millstones, labour hamster-like in wheels, and form a crude production line. Gilliam states that this scene anticipates Brazil’s depiction of dehumanising production: ‘The cogs are always human. I think people use machinery as a way of avoiding machinery, but still somebody either is the machine, or is in control of the machine or has bought the machine. It’s always intrigued me how people are the system, and not the technologies’ (McCabe 1999: 72). The oil change visuals particularly emphasise this sense of bodily technology and Gilliam’s sense of bricolage, as the oil is derived from dinosaur fossils and pumped into human bodies, or at least their technological carapaces. When Dennis takes stock of the scene and interrupts the chain of human labour to suggest a more efficient method, his misplacement of but just one cog sets off a comical chain of destruction.9 Labourers scream as they drop from the works; gears pick up the fallen and roll out of the shop. Like the suffocating dust that coats the royalty in its crumbling castle, levers and pulleys smash the humans beneath them, victims of the economic dependence on automation – and of Dennis, the efficiency expert.

So begins Gilliam’s steampunk, and, if 1884: Yesterday’s Future emerges from postproduction, we shall see its full embodiment. In December 2010, Variety announced that Gilliam was working with Ollive on 1884, an explicitly steampunk, tongue-in-cheek parody of George Orwell’s 1984 (1948) as voiced by former Pythons. According to an executive producer, 1884 ‘imagines a film made in 1848 with steam power, narrating a tale of laughable imperialist derring-do and espionage set in a futuristic 1884 when Europe is at war’ (Woerner 2010; Hopewell & Keslassy 2010). Though Gilliam’s role is listed as a ‘consulting producer’, and is thus more supportive than directive, this development appears to be the culmination of elements that have become recognisable as ‘Gilliamesque’ throughout his career. The movie’s official website features a mock-up of a newspaper that buttresses its title ‘The Daily Empire’ with warring dirigibles.

One of Steam Driven Films’ trailers explains that 1884 will ‘explore the murky world of Victorian foreign policy’ and ends with a battalion of US Marines riding balloons kept afloat by steam-powered riverboat wheels. In another, a Master of Ceremonies appears onstage in London’s Old Red Lion Theatre to announce ‘the miracle of the steam motion image projection system’, a steampunk projector into which an operator shovels coal. The projector plays a movie ‘made with steam power’ that features a brass spaceship whirling past the moon and trailing an anchor. In the London of 1884, steam-powered dirigibles and dangling double-decker buses exhale black clouds of pollution as they soar past Londoners pedalling flying bicycles through noxious smog while a paperboy hawks news of the lunar landing. A scientist squints into an ornate brass telescope to see firecrackers launched from the moon that announce ‘WE’RE HERE!’ claiming the moon as a colony of the British Empire. Mockingly, the trailers’ imagery affirms Gilliam’s and steampunk’s anti-Empire ideology and celebrates what Gilliam always does best: strip away the sheen of nostalgia for some fictitious past in which life was somehow better and render in exquisite detail the historical processes that recycle humans into expendable objects, assembling the crude and cruel empires that eventually crumble under the self-indulgence of the powerful and exploitation of the cogs.

Notes

1 Inspired by Harvey Kurtzman’s Mad magazine, Gilliam cites Kurtzman as his ‘hero’ and worked as an assistant editor on Help!, which was also created by Kurtzman (Adams 2010).

2 Coincidentally, Michael Garrison’s television series The Wild, Wild West (1965–69), which infused the western genre with science fiction and the aesthetic that would become known as steampunk, was broadcast at the same time Monty Python was forming.

3 Though Gilliam did not design it during his tenure at Help! John Cleese appeared in the fumetti, ‘Christopher’s Punctured Romance’, about a man who develops an obsessive ‘relationship’ with his daughter’s Barbie doll (see Crossley 1965; Wardle 1996).

4 Whereas this film was initially slated for a 2012 release, the Internet Movie Database lists it as still being in post-production at the time of writing.

5 Tim Ollive and Terry Gilliam have collaborated on Monty Python’s Life of Brian, Time Bandits, Brazil, The Adventures of Baron Munchausen, The Fisher King (1991), Twelve Monkeys, Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas (1998), and The Imaginarium of Doctor Parnassus (2009).

6 George Lucas praised this scene, which Gilliam had done ‘just to show’ directors such as Lucas and Steven Spielberg ‘that you could do it for a couple [sic] fivers instead of millions’ (Marks 2010: 60; Christie & Gilliam 2000: 98–9).

7 Jabberwocky uses existing paintings to illustrate bits of the story and a cartoon background, in which an animated iris slams shut on the ‘fairy tale’ ending but the rest is live-action. In Carroll’s Through the Looking Glass (1865), Alice finds the ‘Jabberwocky’ nonsense text in a book and says it is ‘all in some language I don’t know’ (Christie & Gilliam 2000: 65).

8 As Marks describes, ‘sections of the panel “Hell” from Bosch’s The Garden of Earthly Delights, depicting horrendous human suffering, are spliced with Bruegel’s similarly unsettling The Triumph of Death’ (2010: 48). As the narration continues to explain the darkness of the Middle Ages, Gilliam also juxtaposes Bruegel’s Tower of Babel to envision the horror of the monster with serene pastoral scenes in his ironically titled The Merry Way to the Gallows (ibid.).

9 Ironically, Gilliam notes in the commentary, the first visible injury happens to a worker whose finger kept getting smashed by another extra during filming.

Works Cited

Barthes, Roland (1975) S/Z: An Essay, trans. Richard Miller. New York: Hill and Wang.

Bowser, Rachel and Brian Coxall (2009) ‘Material History: The Textures, Timing and Things of Steampunk’. Paper presented at the annual convention of the South Atlantic Modern Language Association, Atlanta, GA, 6 November.

——(2010) ‘Introduction: Industrial Evolution’, Neo-Victorian Studies, 3, 1, 1–45.

Christie, Ian and Terry Gilliam (2000) Gilliam on Gilliam. London: Faber.

Crossley, Dave (1965) ‘Christopher’s Punctured Romance’, Help!, May, 15–21.

Forlini, Stephania (2010) ‘Technology and Morality: The Stuff of Steampunk’, Neo-Victorian Studies, 3, 1, 72–98.

Gilliam, Terry (1999) ‘Director’s Commentary’, Monty Python and the Holy Grail (1975). Directed by Terry Jones and Terry Gilliam. Culver City: Sony Pictures.

——(2006) ‘Special Features: Terry Gilliam’s Featurette: Episode Four’, Monty Python’s Flying Circus: Terry Gilliam’s Personal Best. DVD. Directed by Terry Gilliam. New York: A&E Home Video.

Gilliam, Terry and Michael Palin (2001) ‘Special Commentary’, Jabberwocky (1977). DVD. Directed by Terry Gilliam. Culver City: Sony Pictures.

Jones, Jason B. (2010) ‘Betrayed by Time: Steampunk & the Neo-Victorian in Alan Moore’s Lost Girls and The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen’, Neo-Victorian Studies, 3, 1, 99–126.

Marks, Peter (2010) Terry Gilliam. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

McCabe, Bob (1999) Dark Knights and Holy Fools: The Art and Films of Terry Gilliam. New York: Universe.

Monty Python and Bob McCabe (2005) The Python’s Autobiography. London: Orien.

Nevins, Jess (2008) ‘Introduction: The 19th-Century Roots of Steampunk’, in Ann VanderMeer and Jeff VanderMeer (eds) Steampunk. San Francisco: Tachyon, 3–11.

Sterritt, David and Lucille Rhodes (2004) Terry Gilliam: Interviews. Jackson: University of Mississippi Press.