It’s one thing to get lost in your own madness, but to become lost in somebody else’s madness is weirder.

Terry Gilliam (Lafrance n.d.)

This chapter considers the discourse around fantasy articulated by Terry Gilliam’s The Fisher King (1991). In particular, it examines the film’s central concern with fantasy storytelling and the mental condition of psychosis, which for Sigmund Freud involved the psychotic subject in a defensive movement away from external reality towards a newly-substituted alternative reality. Significantly, The Fisher King is not the first film (nor the last) where Gilliam explores the connections between fantasy storytelling and psychosis and their implications. For example, in Brazil (1985) Sam Lowry’s (Jonathan Pryce) escape into fantasy ultimately means that he is unable to save himself from physical torture in the real world, suggesting that fantasy might be seen as a dystopian rather than a utopian space. And in Twelve Monkeys (1995) L. J. Washington (Frederick Strother), an asylum inmate, most explicitly expresses the link between fantasy as escape and madness. He says of his diagnosis (while dressed in a black dinner suit, bow tie and pink bunny slippers):

I don’t really come from outer space … It’s a condition of mental divergence … I am mentally divergent in that I am escaping certain unnamed realities that plague my life here. When I stop going there, I will be well.

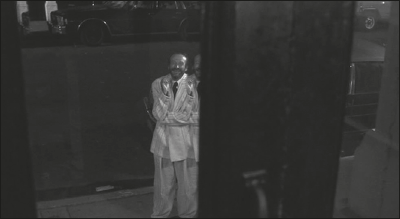

The Fisher King, however, sees fantasy as both an escape and as a redemptive healing space, as Parry (Robin Williams) is rescued from a life of psychotic reality divergence by Jack Lucas (Jeff Bridges) because Jack is able to enter into Parry’s strange medieval fantasy. This chapter, therefore, reflects on The Fisher King’s psychotic, fissured fantasy world and the implications that it might have for an audience lost ‘in somebody else’s madness’.

The Fisher King tells the story of four people – Jack, Parry, Anne (Mercedes Ruehl) and Lydia (Amanda Plummer) – all in different ways trapped in their unhappy lives. Jack is a successful but cynical, shallow and narcissistic New York shock jock who arrogantly goads an unstable caller, Edwin Malnick (Christian Clemenson), into shooting dead seven diners at ‘Babbitts’, a fashionable bar, and then shooting himself. One of Edwin’s victims is Parry’s wife, and the trauma forces Parry first into catatonic shock and then into a defensive fantasy. Having sabotaged his own career and blighted his life, Jack mooches off his long-suffering girlfriend, Anne, whom he feels unable to properly love. The fourth character, Lydia, is a mousy, unfulfilled office worker whom Parry loves from afar.

The film opens on Jack in his role as radio cult personality interviewing callers in order to abuse them and belittle their problems. Our first view of Jack is an extreme close-up of a mocking mouth that fills the frame. Peter Marks observes that while this and other similar shots ‘render him both sensual and monstrous, a figure verbally dominant but visually indistinct’, this first partial sight of Jack establishes him ‘as a fractured or incomplete character, intellectually sharp … but malicious, superior and emotionally vacuous’ (2010: 140). When the camera pulls back it reveals his small, cramped studio, which, as Keith James Hamel remarks, looks like a prison cell, ‘given that the lighting provides chiaroscuro shadows that streak down the walls and resemble jail cell bars’ (2004). Gilliam supports this reading by saying that ‘everything [Jack’s] in is a cage of one sort or another’ (Morgan 1991: 169). Hamel and others also note that Gilliam commonly traps his characters within cages while granting them varying degrees of success at breaking free from them (2004).1 Jack’s cage-like cell functions, according to Marks, as both a fortress and a prison, and suggests that he is confined by his narrow, jaded view of the world; this suggestion is confirmed by his description of the diners at Babbitt’s (possibly named after the materialistic, middle-class and self-satisfied eponymous hero of Sinclair Lewis’ 1922 satirical novel), which he dismisses as a ‘chic yuppie watering-hole’ (2010: 140). He tells Edwin that ‘these people … can’t feel love. They can only negotiate love moments. They’re evil … They’re repulsed by imperfection and horrified by the banal – everything America stands for … They have to be stopped before it’s too late. It’s us or them.’ These casually uttered words, which we come to realise perfectly sum up the nature of Jack’s own emotional prison, have a devastating effect on Jack and Parry’s lives.

The scenes prior to the news report that reveals the massacre at Babbitt’s echo with the mantra, ‘Forgive me’, which Jack repeats nine times as he rehearses for a part in a TV sitcom because he is ambitious to move on from being merely a voice on the radio. The repetition foreshadows Jack’s desperate need for redemption when we find him three years later, having exchanged his luxury lifestyle for a cut-price one and become ‘an intolerant, paranoid, self-pitying misanthrope’ (LaGravenese 1991: 14). He makes a drunken suicide attempt after asking a wooden Pinocchio doll whether ‘ya ever get the feeling sometimes … you’re being punished for your sins?’ Following this, as he is preparing to jump into the East River with weights strapped to his ankles, two vigilante youths who mistake him for a homeless drunk try to set him on fire. A quixotic Parry rushes to his rescue armed with an assortment of found objects refashioned to function as the accoutrements of a medieval Grail knight. Until now both Parry and Jack have been living in a form of limbo as a result of emotional trauma, and the rest of the story charts their developing relationship, mutual redemption and eventual release from their respective cages.

Parry is clearly written as a psychotic character; Freud makes the following concise distinction between neurosis and psychosis. He says, ‘neurosis is the result of a conflict between the ego and its id, whereas psychosis is the analogous outcome of a similar disturbance in the relations between the ego and the external world’ (1993: 213). That Parry suffers from this kind of disturbance becomes evident as the plot unfolds. While twentieth-century New York life continues around him, Parry, previously Henry Sagan, a medieval history professor, retreated into an alternative medieval reality in order to escape the emotional pain involved in acknowledging and remembering his wife’s death, therefore becoming ‘this Parry guy’. The historical past becomes his defence mechanism with which to disavow his personal history, and appropriately enough the verb ‘to parry’ means ‘to ward off’ with ‘a countermove’ to ‘block’ or to ‘turn aside’.

Parry’s defence complies with Freud’s view of psychosis: ‘We might expect that in a psychosis … two steps could be discerned, of which the first would drag the ego away … from reality … while the second step of the psychosis is … intended to make good the loss of reality … by the creation of a new reality which no longer raises the same objections as the old one that has been given up’ (1993: 223). He is similar to many protagonists in Gilliam’s films (such as Sam Lowry in Brazil, Hieronymus Munchausen (John Neville) in The Adventures of Baron Munchausen (1988), James Cole (Bruce Willis) and Jeffrey Goines (Brad Pitt) in Twelve Monkeys and Jeliza-Rose (Jodelle Ferland) in Tideland (2005)). Although Parry is a chaotic figure vibrating on the border of insanity, he nevertheless at times demonstrates total wisdom. His original surname, ‘Sagan’, plays with the words ‘sage’, a character of ‘ancient history or legend traditionally regarded as the wisest of humankind’, and ‘saga’, a ‘story of heroic achievement’.2

Parry’s ‘new reality’ is recreated out of fragments of his previous academic life. Freud writes:

In a psychosis, the transforming of reality is carried out upon the psychical precipitates of former relations to it – that is, upon the memory-traces, ideas and judgements which have been previously derived from reality and by which reality was represented in the mind. But this relation was never a closed one; it was continually being enriched and altered by fresh perceptions. Thus the psychosis is also faced with the task of procuring for itself perceptions of a kind which shall correspond to the new reality; and this is most radically effected by means of hallucination. (1993: 224)

Parry lives in the basement boiler room of the apartment block that he inhabited before the tragedy and his subsequent illness. He rationalises and accounts for his new reality and his basement home by describing himself as ‘the janitor of God’, which coheres with his medieval Grail knight identity, which in turn is constructed out of memory fragments (‘psychical precipitates’) from his previous reality as a medieval history professor. His psychosis is exhibited as he hears voices, sees ‘little fat people’, believes himself to be on a quest for the Grail, and yearns after Lydia, whom he implicates in his medieval fantasy by writing her as a damsel in distress whose affections he must earn by performing heroic deeds. As new characters or objects arrive in his life, such as Jack or the Grail, he then also writes them a role that corresponds to his new identity. In this way Parry’s turbulent fantasy existence is conducted on the margins of modern city life, and the two worlds are linked, so we can share in Parry’s hallucination via Gilliam’s employment of fantastic architectural styling. There are castellated mansions, monumental tower-blocks and Dante-esque streetscapes populated by the city’s down-and-outs that build to an ‘evocation of New York City as a magical landscape filled with medieval flourishes and hellish visions of danger’ (Morgan 1991: 153).

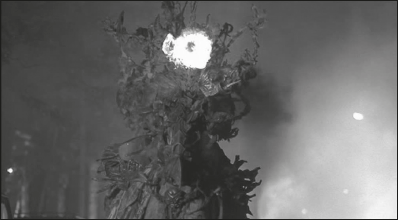

If our first sight of Jack is fragmented, then as Marks notes, ‘our first view of Parry is also visually occluded’, and in the scene where he rescues Jack he ‘appears magically in silhouette, speaking the words of the knight he believes himself to be, but filtered through Gilliam’s particular brand of antic humour: ‘Hold varlet, or feel the sting of my shaft!’ (2010: 141). As we get to know Parry and his world it becomes clear that two medieval motifs are used to express his psychotic break from reality. The first is the Red Knight – a mysterious, fire-breathing, galloping spectre, half horse and rider, and half dragon – which pursues and terrifies Parry. The second is the Holy Grail. After rescuing him from the ruffians, Parry tells Jack that he has been ‘chosen’ to retrieve the Grail, which belongs to a Fifth Avenue billionaire.

Learning that Parry’s madness is a result of his actions, Jack firstly attempts (and fails) to obtain redemption from the prison of his guilt by giving Parry money. Parry’s response is an act of generosity: he gives the money away to a ‘real’ down-and-out. This gesture highlights the cultural and temporal differences between the two characters: Jack inhabits present-day, materialist New York where money is the signifier of status, while Parry lives, at least in his mind, in an antique world of the spirit where hard currency has no currency, and where the duty of a knight-errant is to care for the poor and helpless. It is obvious that Jack’s parole cannot be purchased so easily.

The film is, after all, a fairy tale of redemption, and at its heart lies the eponymous legend of ‘The Fisher King’, an ancient source text adapted for many Christian-themed redemption stories including Chrétien de Troy’s Perceval, le Conte du Graal (12th century), Wolfram von Eschenbach’s Parzival (13th century) and Sir Thomas Malory’s Le Morte d’Arthur (1485), all of which explore the tale of a knight of King Arthur’s court and the quest for the Holy Grail, as Jim Holte notes in this volume (see also Weston 1920). Parry tells Jack his version of the ‘The Fisher King’ story while they lay on the grass in Central Park.

As in Parry’s story, the Fisher King of many of the adaptations of the traditional tale suffers from a wound that will not heal until Perceval, a somewhat foolish knight yet one pure of heart, enables his cure by means of the Holy Grail. Elements of both Parry and Jack’s lives echo that of Perceval, and Gilliam says that ‘both of them is a Fisher King and both of them is a Fool’ (Morgan 1991: 156). Parry’s name is clearly based on Perceval and its many versions, such as Parsifal, Parzival, Percival and Peredur. Jack himself, while his name can be read as a version of ‘knave’ (meaning a male servant, a young prince, or even rogue), is also a onetime ‘king’ of the New York airwaves, who actively sought ‘a life full of power and glory and beauty’, and was guilty of great arrogance. He played with fire (goading Edwin to stop the yuppies), and while it was Parry (and indeed Parry’s wife) who were most obviously wounded, Jack also suffered a reversal of fortune of a type commonly depicted in the genre of tragedy (see Sternberg 1994).

The story that Parry tells reiterates many of the film’s wider themes. It shows the power of fantasy and myth to act as a precipitate of and a window through which to view the struggles of the individual. Its theme suggests the folly of not recognising the value of what is being offered, and instead searching after material wealth at the expense of spiritual or psychological worth. The story is also about active denial, refusing reality. It is also a story about compassion, helping those who are in need of help, and about how the self-serving are not really alive. Finally it is about identity slippages, for example, as Jack and Parry both vie for the position of Fool and the King.

Although the tone and style of the tale of ‘The Fisher King’ place it in a medieval setting, its message adapts easily to modern New York. And although the King’s wounds are apparently physical, Parry’s version implies that the real wounds are in fact psychological: ‘Life lost its reason. He couldn’t love or be loved’, and ‘Sick with experience, he began to die.’ These phrases echo Jack’s words to Edwin when he says that the ‘yuppies’ are unable to feel love, but he might also be referring to himself because until the final scenes he is unable to love Anne. Both ‘The Fisher King’ story and the film are concerned with healing the human spirit, and the film attributes story itself with redemptive power.

In the medieval tale, it is an act of hubris – the Fisher King reaching into the fire after the Grail whilst believing himself ‘invincible, like a god’ – that causes his apparently incurable wound. In the film, Jack’s inflated narcissism leads him to abuse his responsibility as broadcaster. Gilliam reminds us how far Jack has fallen when he has Jack drunkenly tell the Pinocchio doll about Friedrich Nietzsche’s idea of ‘higher man’ from part four of Thus Spoke Zarathustra (1892), which features a collection of characters, two of whom are kings and one a voluntary beggar. Zarathustra, like Parry, and perhaps also like Jack, is forced into convalescence as the world of men has made him ill, ‘sick still from my own redemption’ (Nietzsche 2006: 176). Jack tells Pinocchio that, according to Nietzsche, ‘There are two kinds of people … People destined for greatness … And then there’s the rest of us … the Bungled and the Botched … the expendable masses.’

At the film’s start Jack clearly believes himself to be the former kind, ‘destined for greatness’, but in fewer than seventeen minutes into the film he has reached the point where he feels himself to be ‘one of the Bungled’. When he eventually returns to broadcasting, towards the film’s end, he again refers to himself as ‘Bungled’, but it is not until he realises finally that ‘there is nothing special’ about him, that his journey of self-discovery reaches the point where he can redeem himself by curing Parry. The cure involves bringing Parry the Grail, symbol of divine grace, of salvation, resurrection, redemption and cure. The Grail is also truth, and in the context of this film, truth means having self-knowledge, and the healing process of safely releasing repressed memory from its guarded chamber in the unconscious.

Parry’s moment of self-knowledge and recovered memory is still some ways off as he finishes telling his tale of ‘The Fisher King’ to Jack. He says: ‘I think I heard that at a lecture once.’ We have already seen the typescript of the tale, kept hidden from Parry by the janitor, and we know that he authored this version of the tale himself in his previous existence as Henry Sagan. As Parry begins to consider how he knows of the story, memories of his own past threaten to break through his defence and in a classically Freudian gesture the repressed returns, in this case in the form of the Red Knight. Freud notes that ‘probably in a psychosis the rejected piece of reality constantly forces itself upon the mind, just as the repressed instinct does in a neurosis’ (1993: 224). A ‘screen memory’ may lie close to a significant (repressed) memory but not have any other obvious connection, and as such the hallucinated Red Knight is associated with Parry’s rejected reality. At the same time the Knight is both a substituted symbol inserted in place of the traumatic memory and a mechanism for displacing it.

On this occasion Parry succeeds in blocking his memory and the Red Knight withdraws, but successful repression is only temporary as the trauma catches up with him in a later scene. This later scene takes place after, having failed to buy his own redemption with hard cash, Jack plays Cupid between Parry and Lydia. This second shot at salvation fails, too, because the moment when Parry seems about to attain his love object is marked with terror. Parry and Lydia exchange a kiss outside Lydia’s apartment which triggers a flood of memory; the vision of the Red Knight rears up and Parry is again pursued by the (k) nightmare of his defence-symbol after Parry mistakes a neon sign outside Lydia’s apartment for the sign over the door of the bar where his wife was murdered.

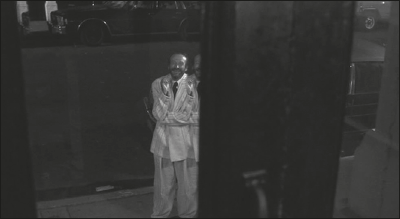

Parry sees the sign (and the viewer also sees the sign through Parry’s eyes). He is positioned outside the apartment building, while the camera is inside, looking out at him through the glass doors. Parry moves to his left, and his image is caught in the splitting effect of the glass door’s bevelled edge. We see two Parrys, side by side. The camera pans in from the long shot to a close up of Parry’s face, split into two overlapping images, clearly literalising his psychotic mind-state.

Parry the fissured king standing outside Lydia’s apartment

Parry in two minds as the repressed returns

In a typically Gilliamesque reversal, the kiss that Parry and Lydia share is the switch that leads ultimately to Parry’s catatonic state. Instead of the fairy tale prince kissing Sleeping Beauty awake, Gilliam gives us Parry’s princess kissing him to sleep. Before he can find the solace of sleep, though, Parry’s surge of love and the awakening of his sexuality undermine his defensive medieval fantasy and activate his memory of the kiss between him and his wife immediately before she is shot.

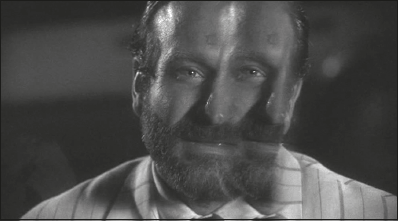

The gruesome, carnal image of the Red Knight pursues Parry as he flees through the streets of Manhattan. The sequence is intercut with scenes from his memory as he is forced to recall it. This is a moment of retroactive understanding for the viewer who is obliged to review what they know of the Red Knight, the exact identity of which has been unclear up to this point. The flashbacks reveal that the look of the Red Knight is partly composed from the grisly appearance of Parry’s wife’s head after she has been shot and partly from the image of Parry’s own face as he is splattered with gore. The Red Knight also carries a strong association with the shooter, Edwin. This becomes evident as an image of the Knight blasting fire is placed either side of the image of Edwin firing his shotgun. Until this moment of revelation (for both Parry and the viewer), the death scene had been hidden behind a composite image of the sensory images Parry received immediately prior to and immediately after the traumatic moment of death. So the blast from the gun, the blood and the affect of fear and horror had metamorphosed into the Red Knight, both in Parry’s mind and in our vision.

The Red Knight, the inside of Parry’s defence

The image of Parry’s wife after the shooting

Henry Sagan, mid-trauma

Two other images from earlier in the film link the images of the bloodied faces and the Red Knight. These linking images are found in Parry’s basement home. The first is painting of a knight on the wall. The paint has run and looks like dripping blood, and there is a tiny skull stuck onto the knight’s helmet. The other image is a page torn from a manuscript showing the picture of a knight, this time with the head obliterated by a starburst of red paint. The Red Knight therefore is the inside of Parry’s defence literalised on screen. The viewer sees the knight when Parry sees him, and so is also inside Parry’s mind, seeing Parry’s hallucination as it threatens the eruption of the repressed unconscious into his conscious mind. The Red Knight is the dangerous fissure in the fabric of Parry’s (and the film’s) fantasy world, just as the original moment that it resembles is the wound that caused the fissure in Parry’s reality that drove him to seek refuge in fantasy. Of course it is not the Red Knight itself that Parry fears, but what it represents, which is the horrific scene of his wife’s death.

Painting of a knight from Parry’s wall with skull and bones

Manuscript image of a knight with an exploding head

Parry runs from the Red Knight through the streets of New York to the place where he first encountered the suicidal Jack and where he is now met by the same vigilante youths who severely beat him. The only recourse left open to Parry is to retreat into catatonia which keeps him unconscious in his hospital bed while a (temporarily) unaware Jack leaves Anne, and prematurely resumes his radio career, believing for a while that his debt to Parry has been paid. His conscience is not clear though as he agonises to an unresponsive, bedridden Parry about his own responsibility and role. Finally, because, as Gilliam says, ‘the film is about becoming selfless and breaking down the ego’, he leaves the hospital to retrieve the Grail (Christie & Gilliam 2000: 196).

Jack breaks into Langdon Carmichael’s castellated mansion dressed in a Parryesque combination of medieval-looking garments and using equipment harvested from Parry’s grotto-like home. Once Jack takes Parry’s delusion seriously it starts to take on a physical reality. At one point Jack (and the audience) hears the Red Knight’s mount neigh, and he says: ‘I’m hearing horses now, Parry would be so pleased.’ Shortly after this he sees Edwin on the stairs. Morgan says that ‘as Jack becomes totally drawn into Parry’s world, effectively becoming Parry, the film gets more and more skewed towards that point of view, where it doesn’t show New York for what it is but as Parry himself sees it’ (1991: 157).

Parry’s cure is finally realised when Jack brings him the cup that he believes to be the Grail. Although it is Jack who has carried the Grail to Parry and who brings about his cure, the action also results in Jack’s own redemption, a major turning point in his journey being the moment when he decides to save Carmichael from accidental suicide.

There has been an exchange here. Parry and Jack are now both the King and the Fool; they have cured each other. This complicates the structure of ‘The Fisher King’ tale, in which Perceval hands the King the Grail (which is by his bedside all along). In the tale this gesture heals the King of his wounds, whereas in the film it heals them both. On waking, Parry says: ‘I had this dream, Jack. I was married to this beautiful woman. You were there too. I really miss her Jack. Is that okay? Can I miss her now?’ Having slipped back into sanity and reality, and at last freed from their respective cages, Parry’s of denial, and Jack’s of soul-sickness, they can start living again. Jack is reunited with Anne and Parry with Lydia.

It is typical of Gilliam to blend the ordinary and the extraordinary in a way that suggests the irredeemable entanglement of madness, fantasy and dreams, and in itself this points towards his status as a creator of troubling (psychotic) worlds on screen. Many commentators have noted the connections between cinema and the dream state, which Freud compared with the psychotic state as they both involve ‘a complete turning away from perception and the external world’ (1993: 215). The dreamer and the psychotic may both turn away from the external world, but a key difference is that the psychotic carries the dream world, the divergent reality, into everyday, waking life whereas the dreamer does not. Therefore, the boundaries between fantasy and reality in psychosis are indistinct or nonexistent, as indeed they are in all of Gilliam’s films. For example, in the final scenes of Brazil it is impossible to identify the moment when the viewer moves from objectively watching Sam being strapped into the torturer’s chair, to being inside Sam’s mind as he hallucinates an alternatively reality where he is rescued by Archibald Tuttle (Robert de Niro) and Jill Layton (Kim Greist). Similarly, in The Fisher King, the camera repeatedly moves seamlessly from an external, objective viewing position, such as one of witnessing the dialogues between Parry and Jack, to an intersubjective position also able to share Parry’s distinctive point of view.

One such moment of intersubjective viewing occurs in the only scene in which Gilliam deviated significantly from LaGravenese’s screenplay. This scene takes place in Grand Central Station during the evening rush hour as Parry waits for Lydia on her way home from work. As Parry sees Lydia enter the station the hurrying commuters suddenly stop rushing, pair up and start waltzing. Lydia sways gracefully through the crowd of dancers followed by Parry. Just as suddenly, the commuters resume their hectic onwards rush as Lydia passes beyond Parry’s orbit. Peter Travers writes of this scene in Rolling Stone that ‘in a breathtaking scene … Parry follows Lydia to Grand Central Station and watches her in love-struck awe, oblivious to the fact that the rest of the rush hour crowd has broken into a waltz’ (1991). This reading, then, uses the dancing couples as a way of representing Parry’s single-minded obsession with Lydia. We are in Gilliam’s mind’s eye, seeing Grand Central Station as he sees it.

An alternative way to think of this scene, though, is that we share the point of view of Gilliam’s onscreen stand-in, Parry. He does not see the world as Jack does, for whom the station is just another ordinary public New York space. Parry’s vision is filtered through his romantic sensibility that, like Gilliam’s, finds magic, beauty and meaning lying just under the surface of the mundane. But we should remember that one of the functions of the Fool is to produce utterances that, although they might sound like nonsense, actually constitute truth and wisdom. For example, Parry loves Lydia and sees her as beautiful, graceful and transformative of any place she inhabits, and by the end of the film that is what she has become. Nevertheless, no matter which reading is accepted, the scene remains a metonymical, symbolic moment strongly suggestive of Gilliam’s persistent relationship in his films with reality/fantasy, sanity/madness and rationality/romance.

It is not sufficient, though, for the viewer to be able to see the world through Gilliam/Parry’s eyes because the magical transformation has also to work within the narrative between characters, as well as beyond it, between film and audience. Parry’s unconscious response to Jack as ‘the one’ who has been sent to heal his psychic wounds by securing the Grail is answered when Jack does finally enter into Parry’s fantasy, and it is Jack’s participation in Parry’s delusion that affects the cure. So, in The Fisher King fantasy not only provides an escape from reality but is also the cure for life’s ills. This suggests that Gilliam shares a view of fantasy as transformative in common with J. R. R. Tolkien, author of The Lord of the Rings novels (1954–5), which he saw as a particular ‘gift’ of fantasy, which Tolkien named ‘recovery’. He used the term to express his belief in the power of fantasy to alter the way we look at our everyday world, so that we (re-)gain a clear view. Tolkien also considered fantasy to possess among its valuable gifts that of escape and consolation. Escape does not, for him, carry negative connotations. Instead, he means the word to be understood as ‘departure’ and ‘imagination’. Tolkien says that escape is ‘very practical, and may even be heroic’; this is because it enables us to gain insight, and to learn again the value of things, which we might else have forgotten (1966: 33–99). It is clear that Parry and Jack both escaped into fantasy for good reasons and it is also clear that fantasy served them both well in the end.

Finally, fantasy’s third gift, for Tolkien, is consolation, which is the joy we feel at the miraculous or surprising turn of the happy ending from the possibility of tragedy. Tolkien calls this moment Eucatastrophe, when catastrophe is averted, and explains, ‘the eucatastrophic tale is the true form of fairy-tale and its highest function’ (1966: 85). Not to be outdone The Fisher King has four endings. The first is when Jack is conducting the sing-along in the mental hospital and Parry is reunited with Lydia; in the second Jack declares his love to Anne; the third sees Jack and Parry reunited, lying naked on the grass; and the fourth sees fireworks over the New York skyline. Marks writes that the ending in which ‘a fireworks display … traces out THE END in the sky, harks back to the fantasy endings of Jabberwocky and Baron Munchausen, signalling that, for all its tough take on the reality of contemporary New York, a space remains for the miraculous’ (2010: 149).

In addition to possessing Tolkien’s three gifts, the film also follows the ancient and universal mythic structure of the quest, which has the protagonist(s) leaving home to undergo trails and challenges, battle with the monster, journey to hell, face a real or symbolic death, and return to life renewed, often to be rewarded by marriage (see Eliade 1963). Furthermore, in The Encyclopedia of Fantasy, John Grant sees The Fisher King as an ‘instauration fantasy of a very high order’ (1999: 354). In turn, John Clute notes the definition of ‘instauration’ as ‘restoration after decay, lapse or dilapidation’ and as ‘the action of restoring or repairing; restoration, renovation, renewal’; he identifies instauration fantasies as those ‘in which the real world is transformed’, often focusing on ‘processes of learning’ tending to ‘emphasize its difficulty’ (1999: 501). Grant says, ‘when we see the Red Knight we are experiencing a perceptual shift that allows us access to a perfectly valid alternative reality; and the kitsch goblet does indeed restore the Fisher King to life’ (1999: 354).

Like The Fisher King, as an instauration fantasy frequently contains ‘within its text a fictional book, whose title is that of the real text, and whose contents reveal … the true story’ (Clute 1999: 501). These fantasies usually begin in the mundane world and involve a slippage into the magical world (Parry’s mind). Clute says that the threshold tension between worlds commonly invokes ‘feelings of stress’, perhaps due to a ‘sense of the precariousness of the psyche’ at these moments; later he remarks that there is a ‘constant interrogative tonality’ to such self-reflexive narratives that ‘point to themselves as being “stories” which extends to the “nature of fiction itself”’ (ibid.). In the end, Clute says that the instauration fantasy ‘is a story about finding out the truth, and living with the consequences’, and he remarks that on the edge of the millennium it was ‘the cutting edge of fantasy – the place where fantasy has no excuse not to be’ (ibid.). All of this points to Gilliam as a skilled fantasist who regularly invites us over the threshold into his idiosyncratic world, and if it is ‘weird’ being in somebody else’s madness, at least he is in there with us.

Notes

1 For example, Kevin and the dwarfs are caged in Time Bandits (1981); dream girl Jill is caged in Brazil (1985); cages in the form of the Sultan’s torture organ and the King of the Moon’s bird cage appear in The Adventures of Baron Munchausen (1988) and James Cole is imprisoned in a Panopticon-like cage in Twelve Monkeys (1995).

2 All definitions come from the Oxford English Dictionary.

Works Cited

Christie, Ian and Terry Gilliam (2000) Gilliam on Gilliam. London: Faber.

Clute, John (1999) ‘Instauration Fantasy’, in John Clute and John Grant (eds) The Encyclopedia of Fantasy. London: Orbit, 500–2.

Eliade, Mircea (1963) Myth and Reality, trans. W. R. Trask. New York: Harper and Row.

Freud, Sigmund (1993 [1924]) ‘The Loss of Reality in Neurosis and Psychosis’, Alan Tyson and James Strachey (eds and trans.) On Psychopathology: Inhibitions, Symptoms, and Anxiety and Other Works, vol. 10, Harmondsworth: Penguin, 219–6.

Grant, John (1999) ‘The Fisher King’, in John Clute and John Grant (eds) The Encyclopedia of Fantasy. London: Orbit, 354.

LaGravenese, Richard (1991) The Fisher King: The Book of the Film. New York: Applause.

Marks, Peter (2010) Terry Gilliam. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Morgan, David (1991) ‘Interviews with Terry Gilliam’, in Richard LaGravenese (ed.) The Fisher King: The Book of the Film. New York: Applause, 153–71.

Nietzsche, Friedrich (2006 [1892]) Thus Spoke Zarathrustra, Adrian Del Caro and Robert Pippin (eds. and trans.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Sternberg, Doug (1994) ‘Tom’s a-cold: Transformation and Redemption in King Lear and The Fisher King’, Literature/Film Quarterly, 22, 3, 160–9.

Tolkien, J. R. R. (1966) ‘On Fairy-stories’, in The Tolkien Reader. New York: Random House, 33–99.