The imagination of a boy is healthy, and the mature imagination of a man is healthy; but there is a space of life between, in which the soul is in a ferment, the character undecided, the way of life uncertain, the ambition thick-sighted: thence proceeds mawkishness, and all the thousand bitters which those men I speak of must necessarily taste…

John Keats, in his preface to Endymion (1818: 60)

It was just a coincidence, but around the time of my parents’ divorce, I watched Terry Gilliam’s Time Bandits (1981) dozens of times on HBO. Enthralled at twelve or thirteen, I never sensed that critics might call it ‘a lot of frippery’ (Rea 2004: 51). It was about a boy I recognised, Kevin (Craig Warnock), who was about my age, with a rich, imaginative fantasy life, a world of books and head-bound adventure. I admired him immensely. And even though I had no idea then who Terry Gilliam was, I now know why Gilliam also identifies with Kevin (see McCabe 2004: 139).

Gilliam’s film frames Kevin’s fantasy life and his encroaching transition to adulthood amidst the architecture of inattentive middle-class parents (played by David Darker and Sheila Fearn) and suburban ennui. Kevin’s rather simple search for a family interested in him also reveals acutely the fissures that real-world problems relating to questions of good and evil, parental roles, mind-dulling capitalism and (un)fulfilling employment reveal. Kevin is so immersed in his fantasy life that he is unaware – indeed, unable – to fully understand, let alone articulate, the weight of the world from which he comes and to which he is (probably) going. Part of this immaturity expresses itself in Kevin’s uncritical perspective regarding his beloved heroes, many of whom he meets during the course of the film. This phenomenon is akin to what Patricia A. Matthew and Jonathan Greenberg believe happens with Children’s Literature students, many of whom have beloved and critically uncomplicated childhood memories of classic children’s stories. Like Kevin, and myself before the divorce, these students ‘encounter … children’s texts during the very time of life when they are unconsciously absorbing ideological codes [so] their emotional investment in the ideological legitimacy of such texts is high – so high that these texts appear, ironically, to be uniquely free of ideology’ (2009: 218). Of course, nothing is free of ideology, regardless of the level at which someone is reading (or not) a text. The question Gilliam then poses is whether Kevin’s adventures will direct him down the path of lifelong inquisitiveness and childlike excitement, even as he matures and begins to see cracks in the system, or whether he is doomed to suffer the same fate as his trapped parents.

Despite the omnipresent child-like gaze through which much of the film can, on one level, be viewed, Gilliam – an adult ever suspicious of the world adults have created – seems most interested in the light this gaze casts on the myriad adults around Kevin. Similar to Karen Lury, who watches children in film in order to ascertain ‘the way in which [they] manage not their apparent strangeness, but how they can reveal the strangeness of the world in which they live’ (2010: 14), I am interested in the warped social milieu which adults have created for Kevin. Likewise, Gilliam uses Kevin’s initially uncritical and innocent eye to revisit fairy tales and ancient heroes, because the modern adult world no longer allows (and/or encourages) substantive heroes or meaningful dreaming. In turn, these fairy tales come to life and do what fairy tales are supposed to do: they allow the child ‘to learn language and master the linguistic conventions that allow adults to do things with words, to produce effects that are achieved by saying something … Fairy tales help children move from that disempowered state to a condition that may not be emancipation but that marks the beginning of some form of agency’ (Tatar 2010: 6). Time Bandits, then, is about this process of maturation through stories. But what happens when the adults Kevin has in his life do not say anything of substance? For what purpose is Kevin maturing? Will he be able to choose a different path? What stories from his own life will he learn to emulate? Will he become his parents?

Ian Christie, citing Tzvetan Todorov, argues that Gilliam’s narratives operate in the realm of fantasy, of hyper-reality, where the rational still applies, but the irrational seems, at times, even more persuasive: ‘Gilliam’s heroes … innocents all … are engaged in quests, which lead them into perilous worlds of illusion, poetry and nonsense … latter-day descendents of the heroes of the Grail legend’ (2000: viii).1 Within the context of the film, another word for this fantasy world might be ‘suburbia’. It is precisely these early framing scenes of exaggerated reality (in Kevin’s house) that situate Time Bandits as, at its heart, a wholly ‘suburban’ film. Gilliam announces as much in the opening frames when the camera focuses on a celestial map of some kind (which we will later see is key to the plot) before zooming through it, plunging through outer space and down to earth through the clouds, and then landing on a suburban housing tract (the film ends in almost the opposite manner – the camera withdrawing from earth much the same way it arrived – with the addition of disembodied hands folding up the map).

Gilliam critiques suburbia at the expense of, to use Keats’ term above, immature adults who, alienated from their own existence, are unable to imagine a life of substance, so incapable of living their own lives apart from coveting the material goods held aloft by distant marketing gods. But Gilliam offers hope for the next generation. It is only through Kevin’s eyes, even if he himself is not fully aware of what he is seeing, that this film offers any hope. Peter Marks argues that children, for Gilliam, work ‘as protagonists or as critical observers of the actions and failings of adults … [and, thus] Kevin’s youthfulness [is] social satire’ (2010: 66, 68). Gilliam chronicles the experiences of little people (both Kevin, still a child, and his band of time travellers, who are not taken seriously by almost anyone, including their Godhead employer) who still dare to dream, and argues that all anyone wants is to have both something meaningful to do and a supportive family. Gilliam savages the latter twentieth-century’s fetishised adult and parental construct of the world, the Disneyfied, consumerist version of reality.

Time Bandits explores this disconnect between parent and child. Here it is not the child demanding the latest consumerist fad; rather, the child yearns for an idealised, idolised and mythologised past of love, adventure, community and, ultimately, of family. Put simply, Kevin still dreams of a life of endless possibility, unconstrained by his suburban walls, because he has not yet learned to view them as either barriers or a false security. His parents, meanwhile, repeat only what they are told they want by the ‘idiot box’ in their ‘living’ room, having turned their dreams over to the higher wisdom of game shows and commercials. It is the parents who seem to equate parental duty and love with providing the latest in material excess for their home. Kevin, however, wants only a family to be interested in his interests and is thus forced to light out for his own territory of dreams.

In so doing, Kevin follows a long line of (stereotypically) boyish, imaginative adventures. Like Huck Finn before him, youth is not only not a hindrance but a boon, because of the open-mindedness and adaptability that comes with a still undeveloped sense of cynicism. As in all quests, Kevin doesn’t remain on his own for long, but is joined by a loveable, rather disgusting cast of diminutive adults, his merry band of little men. Kevin joins, as Gilliam calls them, a community of ‘dwarfs’ (Thompson 2004: 5), who at first seem to be on the same quest as his parents: to accumulate things.2 Joseph Campbell tell us that Kevin’s adventure begins in timeless fashion, for all it takes for a hero is, usually, ‘[a] blunder – apparently the merest chance – [which] reveals an unsuspecting world, and the individual is drawn into a relationship with forces that are not rightly understood’ (1973: 51). I saw in Kevin’s journey, and his contention with large and powerful forces beyond his control, my own experience. Here was a young person who lived largely on his own, which, though for different reasons, is what divorce did to me. Kevin is unaware of his coming fall into adulthood and does not realise the fears ahead of him, even as Gilliam’s narrative subtly highlights them for an adult audience.

Because most film critics see Time Bandits as a children’s film, analysis of its cogent critique of suburbia has been lacking. Though neither the US nor the international trailer make the claim, critics mutually agreed that Time Bandits is a family film, often because they do not know how else to classify it. Vincent Canby writes that the film ‘means to appeal as much to very young moviegoers as to their parents, and that’s a problem. These dual objectives result in a film that lands somewhere in between’ (1981). Stanley Kauffmann admits that, initially, he ‘didn’t know Time Bandits was a children’s picture’ (1981: 25). Roger Ebert muses, ‘perhaps Time Bandits does work best as just simply a movie for kids … I’m not sure that’s what Gilliam had in mind’ (1981). But if it is primarily a children’s film, critics note there are some problems; that is, what might be non-threatening to a child in a Disney-type movie is shot in Gilliam’s realistic, if exaggerated, manner and perhaps not really aimed at children. For instance, David Sterritt notes some ‘gross’ moments, like ‘a hungry hero gnawing on a rat’ (2004: 17). Additionally, the film contains such non-kid-friendly elements as Napoleon’s firing squads, Evil Genius’s (David Warner) exploding minions, an arm ripped off in an arm-wrestling contest, the trademark Gilliam rabble that is dirty, ignorant and helpless, as well as a general atmosphere that is so dark it’s a wonder anyone could think it was a kid’s movie. Perhaps thanks to these and other reviews, Time Bandits became ‘a surprise hit in US theaters, suddenly making [Gilliam] a bankable director’ (Lyman 2004: 27); that is, parents went with their children to see the film. And even Gilliam admits to wanting to ‘do a kid’s film, and all these things came out … I wanted to work at a kid’s level through the whole thing, and the kid would be the main character’ (Thompson 2004: 5). But shooting at a kid’s level is not the same as making a kid’s film.

Kevin is the heart of the film, but he is, in his just-prepubescent state, unable to appreciate that which a discerning audience can: namely, that the adult world ahead, comprised of unappreciated work and imaginations controlled by television, is an existence he has little hope of escaping. But, there is hope. The quest at the centre of Time Bandits is simple enough. Kevin, a boy who lives in his own head and among the legends and heroes about which he reads endlessly, goes on a journey. Not knowing if he is dreaming or awake (there are clues suggesting both possibilities at once, a common plot device in films as diverse as The Wizard of Oz (1939) and Hot Tub Time Machine (2010)), he gets sucked up into his own myth-making. One night, there appears in his bedroom a group of small men who have emerged from a time travelling door conveniently located in his wardrobe. Kevin follows them and, after a series of adventures through and beyond time, confronts, finally, the embodiments of both good and evil during a bizarre, quasi-humorous, cataclysmic battle.

Gilliam explains his film: ‘Fantasy/Reality. Lies and truth is an extension of that, and it’s about age and youth. Also death, birth, all those things … a boy going through space and time and history, and never knowing whether it was real or a dream’ (Morgan 2004: 41). Time Bandits is something of an anti-fairy tale, one that deconstructs the fairy tale promise of latter-twentieth-century middle-class suburban existence. ‘Certain fairy tales’, Jack Zipes explains, ‘have become almost second nature to us and not simply because they have become part of an approved hegemonic canon that reinforces specific preferred values and comportment in a patriarchal culture – something that they indeed do – but rather because they reveal important factors about our mind, memes, and human behavior’ (2008: 110). Just as my own parents’ divorce caused me to challenge the stereotypical myths of suburbia as providing default answers to elusive questions, Time Bandits critiques multiple common mythologies. And though Kevin may never quite understand the border between fantasy and reality, the film leaves no doubt that Kevin cannot escape the everyday-world of harsh reality.

If not quality, Kevin and his parents do spend time together

When we first meet Kevin, we see him sitting at the kitchen bar counter, back to the camera. He is poring over an at-first unidentified book while his parents watch television. This scene – short but important – is a reverse angle from the perspective of the television, which commands a complete view of the family tableau before it. Though not a pretty picture, this is appropriate, as the television directs the family’s (in-)action. The father is dressed in a blue tracksuit of some kind (ostensibly suggesting he has exercised after work, but more probably just being what he wears during leisure time) while the mother is in pink loungewear. Seemingly middle-class, work now done, they relax, uncritically enjoying the pitfalls of their station: ennui disguised as choice, inadequate purchasing power disguised as potential upward mobility, and co-habitation disguised as family bonding.

Like medieval barons seated on their thrones – a couch and recliner, they sit in their gendered-appropriate places, á la All in the Family (1968–79) – they are lord and lady of their manor. And yet their apparent peace cannot last, for, as Daniel Thomas Cook argues, ‘conceptually, leisure and consumption appear to be at odds with one another [because] leisure, often conceptualized by theorists and practitioners as an escape from the vicissitudes of productive life, can itself hardly escape the pull of capital’ (2007: 304). This clash of titanic ideas is certainly present here, for the relaxing parents discuss only topics related to material possessions and their sense of inadequacy before this altar. With mail-order catalogues, petty conversation about the neighbours, television and substantive parental duties ignored, they are multi-tasking two decades before the phrase came into vogue.

This scene contains three conversations, a classic suburban palimpsest: Kevin speaking excitedly to his unheeding parents about the ancient world, mother with father and television with parents. Gilliam, with his American roots, well knows the original promotion of the television as being central to the middle-class home. Many early shows representing suburbia on television, especially in 1950s/60s America, ‘created an imaginative vision of a landscape devoid of social competition and striving, a place altogether free from any outside connection to the social and economic concerns of the world “outside”’ (Beuka 2004: 72). And while such programming – the safe and the scripted – may gloss over substantive investigation into real world concerns in favour of a world where father knows best (and, what’s more, can prove it in 23 minutes!), commercials have long represented the crack in the façade. Relentlessly pushing material inadequacy in the service of capitalism, commercials corral viewers, even getting louder so they can still be heard during a trip to the kitchen or toilet. In the world of Kevin’s parents, the programmes themselves are extended commercials, exploiting insecurities and promising false hope. In the show the parents are watching – a game show called ‘Your Money or Your Life’ – the non-winning ‘winning’ options indicate the invisible barrier confronting the middle-class: there is no winning.

Kevin glances up periodically to throw out facts about the ancient Greeks and their fighting ways. ‘Dad’, Kevin asks of the air and, sadly, probably not really of his father, ‘did you know that ancient Greek warriors had to learn 44 ways of unarmed combat? Did you know the ancient Greeks could kill people 26 different ways! … And this king, Agamemnon, he once fought…’ Kevin isn’t so much competing with the television as ignoring it. For how could Kevin compete with the allure of a new kitchen? Though the house’s kitchen is, the screenplay tells us, a ‘modern, fully gadgeted kitchen’, it cannot compare with the space-age graphics of the kitchen on the television. The mother engages the television’s omniscient voice that, like a vampire and with more or less the same intentions, she has unwisely invited into her home, as seen in the screenplay:

Voiceover on TV: Yes, folks … Moderna Designs present the latest in kitchen luxury. The Moderna Wonder Major All Automatic Convenience Center-ette. Gives you all the time in the world to do the things you really want to do! … A washing machine that cleans, dries and tells you the time in three major international cities! A toaster with a range of fifty yards! And an infrared freezer/ oven complex that can make you a meal from packet to plate in 15½ seconds.

Attempting to mask her insecurity, the mother shrugs her shoulders at this positively amazing information. While it is obvious they do not have such a kitchen – a Center-ette, no less – the mother tries to re-exert her superiority over the inferiority-inducing television kitchen by, oddly, claiming that the neighbours have an even better kitchen: ‘The Morrisons have got one that can do that in 8 seconds … Block of ice to Boeuf Bourguignon in 8 seconds … [with feeling] lucky things.’ In her Jungian study of food, Eve Jackson argues that hunting and gathering are part of what make us human; according to the Greeks, the sacrifice of another being (meat eating) defined ‘the conscious as opposed to the instinctual’ (1996: 46–57, 61). But what of a society where hunting and gathering means going to the grocery store and where kitchens prepare our food without us? Are we still fully human? The answer purports to be yes, but only if we can combat this challenge to our humanity in other ways, as the father meekly tries to do: ‘Well, at least we’ve got a two-speed hedge cutter.’ If there is hope for Kevin, it doesn’t appear to be on this path.

The suburban frame of the film set, Kevin’s adventure begins in his bedroom, that sphere of false respite from parents’ control. This scene is, suggests Owen Gleiberman, classic Gilliam: ‘I think of the archetypal Terry Gilliam image – it’s there in both Brazil and Time Bandits – as a peaceful, tranquil setting suddenly disrupted by a force of great violence’ (2004: 34). This great violence is a medieval knight, in full battle regalia, emerging from Kevin’s wardrobe before galloping off into the forest. Kevin pulls the blankets over his head and his room returns, the knight gone even as the night endures. Investigating, he finds a picture of the same knight in the same forest on his wall. But just as he is about to write it off as a dream, his father bursts in and demands to know what all the noise is about. So, the next night, after Kevin has waited for his microwaved food and blended pink drink to ‘go down’ (a prerequisite, his parents argue, of being able to go to bed), he is ready with flashlight and Polaroid camera. But nothing happens; he falls asleep.

When the wardrobe again opens on the second night, it is not a knight, but a band of small, strange men. Kevin shines his torch on them and they panic, scattering like cockroaches. Kevin does not know it yet, but this group will become like a family to him. Suddenly, a giant glowing head appears and chases the dwarfs and Kevin down a corridor that appears out of nowhere. This giant head belongs to Supreme Being (Ralph Richardson), who intones deeply (godhead voiced by Tony Jay): ‘Return what you have stolen from me. Return the map. It will bring you great dangers. Stop now.’ At this point in his young life, Kevin understands little of his parents’ everyday experience. That is, suburbia is designed to reduce anxiety, danger and the need to depend on a map for life’s direction. But the result of this Frankensteinian way of living – which was thought by some to be the culmination of all the best parts of a community – has often been the opposite of that which was intended. In post-World War II suburbia the formerly external, large-scale fears of invasion and the need to defend one’s family against all enemies foreign and domestic are meant to be, but never can be, confined behind closed doors. If our homes are our castles, then the often isolating effects of suburbia mask the dangers which, as Supreme Being accidentally suggests, have always come with risk and a purpose to life. A map represents life outside one’s front door, and there is no doubt such a pursuit brings with it great dangers. Kevin’s parents retreat each night to their castle, keen in their desire to avoid the dangers that Supreme Being lays out, thinking that they have vanquished such threats from without. Still innocent, however, Kevin is not ready to acquiescence.

The conflicts detailed above are seen in every one of Kevin’s escapades, beginning in 1796, at the Battle of Castiglione in northern Italy, a ‘reality’ which Kevin embraces immediately. Finally away from his stultifying suburban life, he is ecstatic to see history come alive in such a way. True to his child-like nature, he takes no empathetic notice of the death and suffering around him. Sneaking into the embattled city, Kevin and the Time Bandits meet Napoleon (Ian Holm), who watches puppets beat each other on stage with much amusement. This whole episode is predicated on Napoleon’s size and how his perceived inadequacy is the cause of him trying to do his best at his chosen line of employment, that is, as conqueror of Europe: ‘Five foot one and conqueror of Italy,’ he says; ‘Not bad, huh?’3 Despite causing fear and death throughout the continent, or perhaps because of this, Gilliam suggests that Napoleon’s conquests are merely to prove his mettle as a (still small) man. Kevin, however, sees only the ‘great’ Napoleon.

Planning theft, the Time Bandits perform an impromptu, ridiculous act for the emperor, which degenerates into them hitting and slapping each other. Terrified that he has failed in his job to amuse the Little Corporal, the theatre owner (Charles McKeown) looks to commit suicide, but Napoleon is thrilled to find people even smaller than himself and intervenes. He tells Kevin: ‘Young man, you stick with these boys, you have a great future.’ Napoleon then dismisses his generals, appoints his new little friends to his staff, and, at dinner, gets drunker and drunker, while contemplating famous short people of history. Meanwhile, Randall (David Rappaport) and the others, looking ridiculous in their too-big uniforms with their too-big hats, at a too-big table with piles of looted gold and treasure, look nervously on, checking their pocket watches, like a certain famous White Rabbit. Everyone in this scene is just a worker (or sees himself as such) wanting to be appreciated, from the theatre owner to the generals, to Napoleon, to the Time Bandits (‘We’re international criminals. We do robberies!’ says Fidgit [Kenny Baker] proudly), and all are loaded with grievances. Though perhaps less spectacular in the suburbs, this sense of needing respect and appreciation for one’s daily output, and often not getting it, is a common source of family breakdown, one that perfect lawns and wide streets cannot assuage.

Next stop: Sherwood Forest. Again, Kevin meets a hero and is bewitched by him, though Gilliam paints Robin Hood (John Cleese) as not the beloved quasi-historical figure in which we so desperately want to believe (and the fact that Hollywood continues to return to this myth shows its endurance), but as a benevolent dictator, something of a forest dandy. Cleese’s Robin Hood is just trying to be successful at his day job of thievery, and in his desire to get ahead observes no honour among his colleagues. He marvels at the Time Bandits’ haul. ‘It was a good day, Mr Hood’, Randall replies, as if discussing cleaning out the inbox on his desk with his boss. Only when Robin Hood thanks them for the contribution to the poor does Randall understand that there is no getting ahead in this world, no rising above one’s station. In fact, even the poor must suffer in return for the Time Bandits’ unwitting beneficence. Gilliam’s trademark rabble stand in line for a handout, where each recipient is promptly hit in the face – men and women alike – by one of Hood’s men. Is this necessary, Robin Hood wonders? Yes, he is assured by his henchmen, it is. There is no free lunch. Hood’s parting gesture is to ask the Time Bandits to stay: ‘There’s still so much wealth to redistribute.’ Kevin, however, sees only a potential family unit, and would like to stay, but he’s pulled away mid-sentence by Randall and the boys.

Kevin then meets Agamemnon (Sean Connery), who credits the boy, an apparent gift from the gods, with helping to slay the Minotaur. The king takes Kevin home, but something is not right in the Agamemnon household. His wife (Juliette James) is unhappy that he returns alive from his travelling for work, it being his responsibility as king to kill the threat from the Minotaur (and, if this is the same Agamemnon from The Odyssey, we know he will later be murdered by his wife and/or her lover). ‘The enemy of the people is dead!’ bellows Agamemnon, as he beckons Kevin to his side. Back in the office, Agamemnon blithely condemns three nobles to death and tells his courtiers to ‘remind the queen that I still rule the city’. Kevin catches none of this, as he occupies himself sketching out great battle scenes, thinking perhaps that this latest potential father is merely busy at work. Though Kevin wants Agamemnon to teach him swordfighting and killing, the king wants to teach him tricks and to use his wits. For the king also wants to be a father, and he has now found a willing son. Kevin says, ‘You know, I never, ever want to go back.’ Young Kevin sees his emasculated suburban father and pines instead for children’s fairy tales where killing others is exciting and romantic. Gilliam the director knows the fantasies of young people even as his Agamemnon knows the weight of everyday headaches, king or not.

Having been spirited away from ancient Greece by his fellow Time Bandits at the moment he was to become Agamemnon’s son and heir, Kevin and company next escape into and out of the dinner pot of a hard-working ogre with back problems. They then wander a desert before running into, like so many people trying to get ahead, an invisible wall, which is broken by the bones – literally – of those who have come before. It is shattered by a skull Randall throws in a fight in order to retain leadership of a group that has agreed to be leaderless. Fairy tales, Maria Tatar argues, can be transformative for their readers and, further, ‘function as shape-shifters, morphing into new versions of themselves as they are retold and as they migrate into other media’ (2010: 56). This lesson of hope and struggling ever onward despite the odds, however, is not a lesson that Kevin learns at home. Instead, he learns it from his new companions who, unlike his parents, have not given up on whatever fairy tale dreams they had as children.

Stepping through the formerly invisible barrier, the Time Bandits arrive at their goal: the fortress of Evil Genius, a boss who, true to his moniker, is merciless to his idiotic sycophants. He believes he needs only the stolen map in order to set himself up as the rightful ruler of the universe. And why does he qualify for this job advancement? Because, he says, he has ‘understanding’. Of what, a minion asks? ‘Digital watches’, he begins:

And soon I shall have understanding of videocassette recorders and car telephones. When I have understanding of them, I shall have understanding of computers. When I have understanding of computers I shall be the Supreme Being. God isn’t interested in technology. He knows nothing of the potential of the microchip. Silicon revolution. Look how he spends his time: forty-three species of parrots; nipples for men.

This is an argument Kevin’s parents know well; essentially, it is the same argument used for the modern kitchens they see on their television. Evil Genius knows what humans want and knows what they will sacrifice (peace, family, self-dominion and so on) to get it. In fact, he has tricked the Time Bandits into coming to his lair by putting words in the mouth of the dumbest bandit: the ‘greatest thing man could want: the goal of everybody’s hopes and dreams … the most fabulous object in the world’. In a significant line that shows Kevin moving toward both maturity and understanding by challenging the model his parents have bequeathed to him, he asks, sceptically, about this modern-day Grail: ‘do you always have to go after money?’

Ignoring Kevin, they run pell mell through a labyrinth and toward an apparent gameshow, a trick by Evil Genius. Studio lights flash, the darkness is illuminated; cheesy game-show music plays; the promises of a beautiful, gleaming Moderna Designs kitchen looms ahead. A sleazy, well-dressed game show host descends the stairs, intoning ‘And here they are, the winners of the most Fabulous Object in the World’. Kevin warns them not to go; he knows through much personal experience that such an Object is but an illusion. Even when Evil Genius produces likenesses of Kevin’s parents, dressed in showbusiness glitter, he is not convinced: ‘It’s a trap!’ he yells. And it is, for the game show host is Evil Genius and Kevin’s parents his minions, now dressed in the same plastic as his living-room furniture, indicating that they have given up all subjectivity for the love of the commercial object.

For the final confrontation, Evil Genius steals the map from Kevin in order to ‘remake man in our own image’. His use of the possessive pronoun is interesting here, as he appears to be referring to himself and his minions. Consequently, he means that he wants man (and woman) to be but a sycophant, ready to do his bidding and not the apparently free-thinking individuals who have long frustrated and elated philosophers and mass manufacturers of all stripes. The film posits, then, that he will not have much work to do with the adults in the world, for he knows how to lure them: shiny objects of technology (and this was before the internet; he didn’t know how right he was). But Kevin, still a child, presents the real problem; Evil Genius knows he ‘is stronger than the rest … a very troublesome little fellow’. Only children (Kevin) and their toys appear to have a chance to defeat Evil Genius. On a Sherman tank, Randall rides to the rescue; other Time Bandits bring to the fight (through time portals) knights, ancient Greek archers, Old West cowboys with six-shooters, and even a small spaceship. But these are no longer children’s toys but real weapons of war and violence, and thus doomed to failure. Gilliam explains this scene as being shot from a kid’s approach to evil: ‘There was a kid, he’s got to go to battle with evil with all these toys you have, your cowboys, your Indians, your knights, that’s what it’s all about. I wanted the messiness of a kid’s playroom’ (Klawans 2004: 152). However, Evil Genius defeats them all, killing Fidgit in the melee. All seems lost.

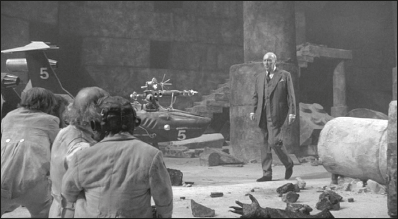

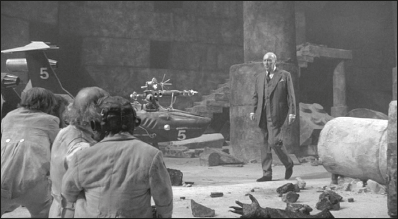

Gilliam knows how to fill a scene with well-placed, meaningful items which, taken in sum, further his arguments. For example, we see the moment just after Evil Genius turns into coal-like stone and explodes in a cloud of flame and smoke. In walks Supreme Being, dapper in a grey suit, a proper elderly British gentleman. A father. Or, a boss. Supreme Being, despite creating the world, abhors a mess and he demands that every piece of Evil Genius be cleaned up (his coal-hand outstretched in the lower right of the frame, in one more attempt to beckon the Time Bandits toward evil). Supreme Being also hates time wasted, so he re-animates Fidgit, if only because being dead is ‘no excuse for laying off work’. The independent contracting jig (theft across time) now up, Randall returns to his supplicating, worker-bee ways. These are unfortunate lessons that Kevin has been taught in his own suburban home, and if he has any chance, he must reject them. But Supreme Being, Randall’s boss, is not having any of it: ‘Of course you didn’t mean to steal [the map]. I gave it to you, you silly man … Do you really think I didn’t know? I had to have some way of testing my handiwork. I think it turned out rather well, don’t you? [Randall looks at him incredulously.] Evil, turned out rather well.’ Order. The system. All is restored and work can resume, which is what Supreme Being desires as proof that he is in charge. Kevin then comes face to face with the ultimate hero: the deity. And, Gilliam suggests, Kevin finds him lacking, for Supreme Being employs dubious explanations and deceitful practices similar in nature to his suburban parents, all in the name of expressions of power and desire for order.

Time to clean up the playroom

Like many employers, Supreme Being is unconcerned when his logic falls apart. Despite claiming to have intentionally set the Time Bandits’ actions in motion, he then demotes the Time Bandits, before taking credit for being a benevolent employer:

Ah, you certainly were appallingly bad robbers. I should do something very extrovert and vengeful with you. Honestly, I’m too tired. I think I’ll just transfer you to the undergrowth department, bracken, small shrubs, that sort of thing. With a 19 per cent cut in salary, backdated to the beginning of time. [Randall and others bow and thank Supreme Being.] Well, I am the nice one … Come on then, back to Creation. They’ll think I’ve lost control again and put it all down to Evolution.

But if the Time Bandits are chastened and accept the order of the powerful and the powerless, Kevin does not know enough to withhold his questions, so he challenges Supreme Being about the nature and importance of Evil in the world:

Kevin: You mean you let all those people die just to test your creation?

Supreme Being: Yes. You really are a clever boy.

Kevin: Why did they have to die?

Supreme Being: You may as well say why do we have to have Evil?

Randall: [Stepping in front of Kevin] Oh, we wouldn’t dream of asking a question like that, sir.

Kevin: Yes, why do we have to have Evil?

Supreme Being: Ah… [Walks away behind a column before suddenly returning] I think it’s something to do with Free Will.

Supreme Being is not used to being questioned in such a manner and, although he seems to agree with his own answer, it also appears after all these millions of years of creation, he just threw out a term humans have been using against themselves for a long time. But why eschew free will, as Kevin’s parents have? The joke, it seems, is on those of us who would go along with the very mythologies we have created to explain our modern world, with its curious mix of business and torpor. Perhaps, the film argues, adults are not so different from how, according to Matthew and Greenberg (2009), children also accept uncritically their own childhood stories.

The fortress of Evil Genius now tidied up, only one of the Time Bandits shows any concern for Kevin (and it is not Randall), but is told by Supreme Being that, no, Kevin cannot come along and join their ‘family’. In a cloud of smoke, they are gone; in this same smoke we return to Kevin’s bedroom where he is being rescued by firemen. ‘Someone’ left something burning in the toaster and it has now burned down the house, which might signal a warning to the parents: next time, purchase the deluxe new kitchen or suffer the consequences. While Kevin is being hustled out by a fireman, his parents, already safe, are worrying about the kitchen equipment. The mother wants to go back in to save the appliances: ‘Let go. I’ve got to save it … I’m going in for the toaster! … Honestly, Trevor, if you’d been half a man you’d’a gone in there after the blender.’ Contrary to how it was sold to him, suburban consumerism has destroyed the father’s last vestiges of masculinity.

And then the final twist, which David Sterritt claims ‘is downright bizarre for a children’s film – an unexpected and unsettling twist that may disconcert young moviegoers’ (2004: 17). Several things happen at once: one of the firemen is Agamemnon/Sean Connery; Kevin looks through his Polaroids confirming that his dream was a reality (or, is his reality a dream?); and, he sees an overlooked chunk of Evil Genius – which caused the fire – in the just-recovered toaster. Kevin warns his parents: ‘Mom. Dad. It’s evil. Don’t touch it!’ Naturally, they do not listen to their child and immediately both put a hand on the ‘concentrated evil’, their last act of marital solidarity. They promptly explode, Kevin and neighbours in bathrobes looking on, the fire crew driving away. Gilliam says that ‘Munchausen had a happy ending, so did Time Bandits. Brazil has an ending that was right for that piece’ (Wardle 2004: 91).4 Yet this ‘happy ending’ leaves Kevin alone in the world, suddenly orphaned. Gilliam expands:

I think it’s a reaction against American films where the learning experience is easy and things work out well … The line that I’ve always liked is when Fidget says, ‘Can he come with us?’ and the Supreme Being goes, ‘No, he’s got to stay here and carry on the fight.’ Now that’s an incredible thing to say in a kids’ movie like that, that it is a battle, that it is a fight, and it doesn’t mean that good wins and bad loses. (McCabe 1999: 98–9)

Kevin’s father is of no help and his alternate father figure, Agamemnon, is now reduced to a kindly fireman, one who probably winks at all the children of burned down houses and who does not even know he is supposed to be a father figure. Kevin now realises consciously for the first time that he is largely on his own (whether or not his parents are actually dead), and, though tragic, this awareness will hopefully aid him going forward. Perhaps the ending, then, is not so much happy as hopeful, as Kevin has moved to maturity and demonstrated that he will not passively accept the suburban inertia, which for so long has been his only model.

* * *

Randall Jarrell writes that ‘a story may present fantasy as fact, as the sin or hubris that the fact of things punishes, or as a reality superior to fact’ (1994: 6). Looking back, I see that before my parents’ divorce I viewed the world in much the same way that Kevin does up until the film’s conclusion. Blending history with the present, confusing mythology and fairy tales with facts, Kevin and I were, as children, unconcerned with adulthood and unable to critique our own fantasies outside of our small worlds. And even though Kevin is presented with the idea, again and again, that his heroes are not all that heroic after all, he is not able to see this at first. The reality that Kevin learns when he watches his parents explode is similar to what I learned all those years ago through the divorce. And yet while Kevin’s parents may be far from perfect, the prospect stretches before him that neither are the ‘real’ heroes he met along his journey and, for now, his solipsistic, materialistic, overwhelmed and alienated parents (or, the memory of them at least) are all he has.5 Kevin and I learned together what young store clerk Sammy learned, through a sudden life-changing decision, in John Updike’s short story, ‘A&P’: ‘and my stomach kind of fell as I felt how hard the world was going to be to me hereafter’ (2004: 601).

Notes

1 For more on Todorov and Gilliam, see Marks (2010: 54, 72–4). Regarding Gilliam and the Quest for the Holy Grail, see Tony Hood’s chapter in this volume.

2 Gilliam argues, ‘But a kid isn’t going to sustain a film, so he’s surrounded with a gang of interesting characters, but they’ve got to be the same height as the kid, so we’re talking about dwarfs, folks’ (Thompson 2004: 5). This immediately recalls other famous dwarfs in movie history, including Disney’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937), who are diamond miners. A key difference is that the Time Bandits want to steal wealth, not work for it, as millennia of unsatisfying work for Supreme Being is what prompts them to try larceny. Further, Gilliam’s dwarfs are not as sweet and cuddly as the munchkins Dorothy meets in The Wizard of Oz (1939); and, though devious, the Time Bandits do not willingly work for ‘the Man’ as do the Oompa Loompas in Willy Wonka & The Chocolate Factory (1971) and Charlie and the Chocolate Factory (2005). Nevertheless, there exists a little bit of all these characters in the Time Bandits.

3 Of course, theatre within theatre within theatre is a common theme for Gilliam the Python. Interestingly, Gilliam claims not to have realised that he has similar theatre scenes set in besieged cities in both Time Bandits and The Adventures of Baron Munchausen (1988) until a reporter pointed it out to him. Then, considering this semi-coincidence, he says: ‘I think it’s me, just making a statement about what is important in life. It’s about how the theatre and entertainment and art, no matter how dire the world is, has to be kept alive’ (Klawans 2004: 158).

4 Here Gilliam refers not to the studio-generated ‘Love Conquers All’ version of Brazil, but his own preferred ending. This classic Hollywood battle is discussed in greater depth elsewhere in this volume.

5 I shared this with Kevin, I believe, even though my own parents were quite different from his, perhaps only qualifying on this list of issues as being, at times, overwhelmed. For their lifelong love and support, this chapter is dedicated to them.

Works Cited

Beuka, Robert (2004) SuburbiaNation: Reading Suburban Landscape in Twentieth-Century American Fiction and Film. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Campbell, Joseph (1973) The Hero with a Thousand Faces. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Christie, Ian (2000) ‘Preface’, in Ian Christie and Terry Gilliam, Gilliam on Gilliam. London: Faber.

Cook, Daniel Thomas (2007) ‘Leisure and Consumption’, in Chris Rojek, Susan M. Shaw, and A. J. Veal (eds) A Handbook of Leisure Studies. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Gleiberman, Owen (2004) ‘The Life of Terry’, in David Sterritt and Lucille Rhodes (eds) Terry Gilliam: Interviews. Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi, 30–5.

Jackson, Eve (1996) Food and Transformation: Imagery and Symbolism of Eating. Toronto: Inner City Books.

Jarrell, Randall (1994) ‘Stories’, in Charles E. May (ed.) The New Short Stories Theories. Athens, OH: Ohio University Press.

Kauffman, Stanley (1981) ‘Stanley Kauffmann on Films’, The New Republic, 11 November, 25.

Keats, John (2009 [1818]), Elizabeth Cook (ed.) John Keats: The Major Works: Including Endymion, the Odes and Selected Letters. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Klawans, Stuart (2004) ‘A Dialogue with Terry Gilliam’, in David Sterritt and Lucille Rhodes (eds) Terry Gilliam: Interviews. Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi, 141–69.

Lury, Karen (2010) The Child in Film: Tears, Fears and Fairytales. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Lyman, Rick (2004) ‘A Zany Guy Has a Serious Rave Movie,’ in David Sterritt and Lucille Rhodes (eds) Terry Gilliam: Interviews. Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi, 26–9.

Marks, Peter (2010) Terry Gilliam. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Matthew, Patricia A. and Jonathan Greenberg (2009) ‘The Ideology of the Mermaid: Children’s Literature in the Intro to Theory Course’, Pedagogy: Critical Approaches to Teaching Literature, Language, Composition, and Culture, 9, 2, 217–33.

McCabe, Bob (1999) Dark Knights and Holy Fools: The Art and Films of Terry Gilliam. New York: Universe.

——(2004) ‘Chemical Warfare’, in David Sterritt and Lucille Rhodes (eds) Terry Gilliam: Interviews. Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi, 135–40.

Morgan, David (2004) ‘The Mad Adventures of Terry Gilliam’, in David Sterritt and Lucille Rhodes (eds) Terry Gilliam: Interviews. Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi, 36–46.

Rea, Steven (2004) ‘Birth of Baron Was Tough on Gilliam’, in David Sterritt and Lucille Rhodes (eds) Terry Gilliam: Interviews. Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi, 47–51.

Sterritt, David (2004) ‘Laughs and Deep Themes’, in David Sterritt and Lucille Rhodes (eds) Terry Gilliam: Interviews. Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi, 16–29.

Tatar, Maria (2010) ‘Why Fairy Tales Matter: The Performative and the Transformative’, Western Folklore, 69, 1, 55–64.

Thompson, Anne (2004) ‘Bandit’, in David Sterritt and Lucille Rhodes (eds) Terry Gilliam: Interviews. Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi, 3–15.

Updike, John (2004) The Early Stories: 1953–1975. New York: Ballantine Books.

Wardle, Paul (2004) ‘Terry Gilliam’, in David Sterritt and Lucille Rhodes (eds) Terry Gilliam: Interviews. Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi 65–106.

Zipes, Jack (2008) ‘What Makes a Repulsive Frog So Appealing: Memetics and Fairy Tales’, Journal of Folklore Research, 45, 2, 109–43.