Europeans and Globalization: Does the EU Square the Circle?

Silvia Merler

Introduction: Europe and Globalization

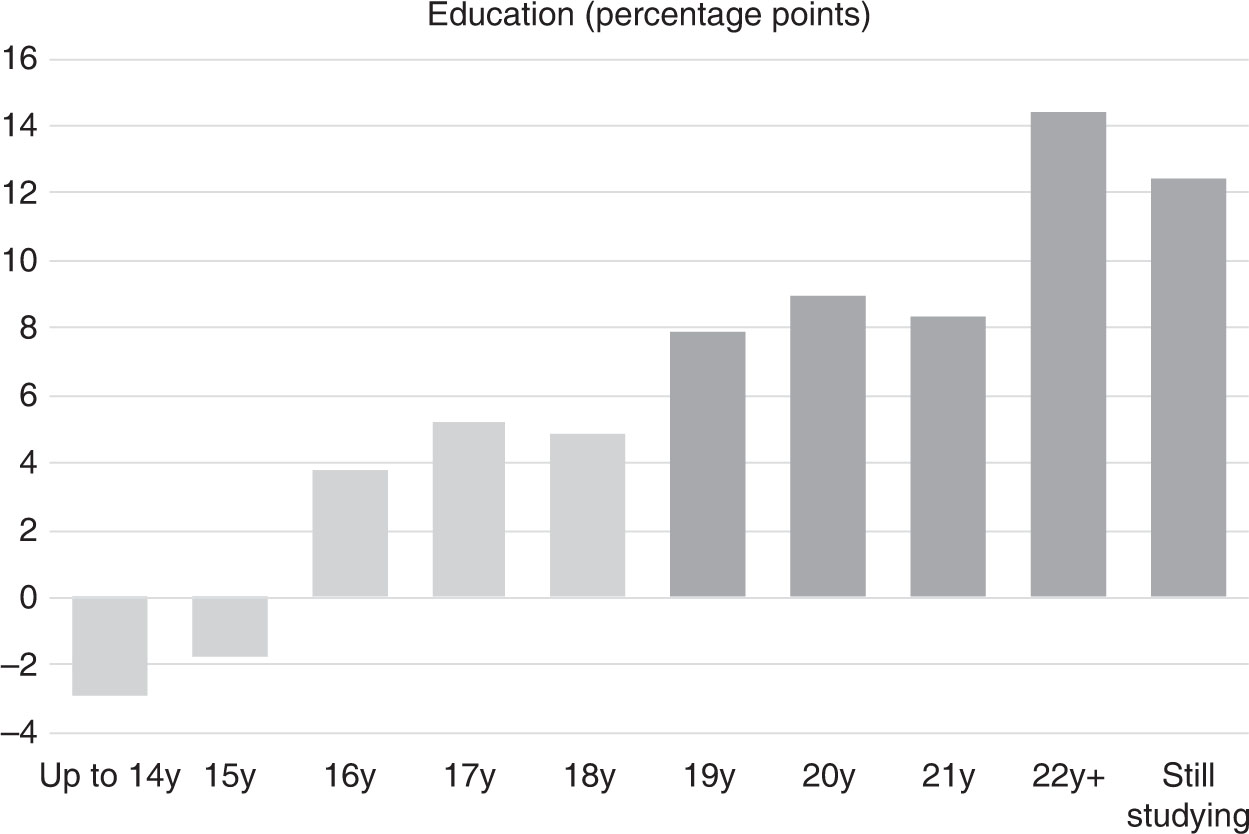

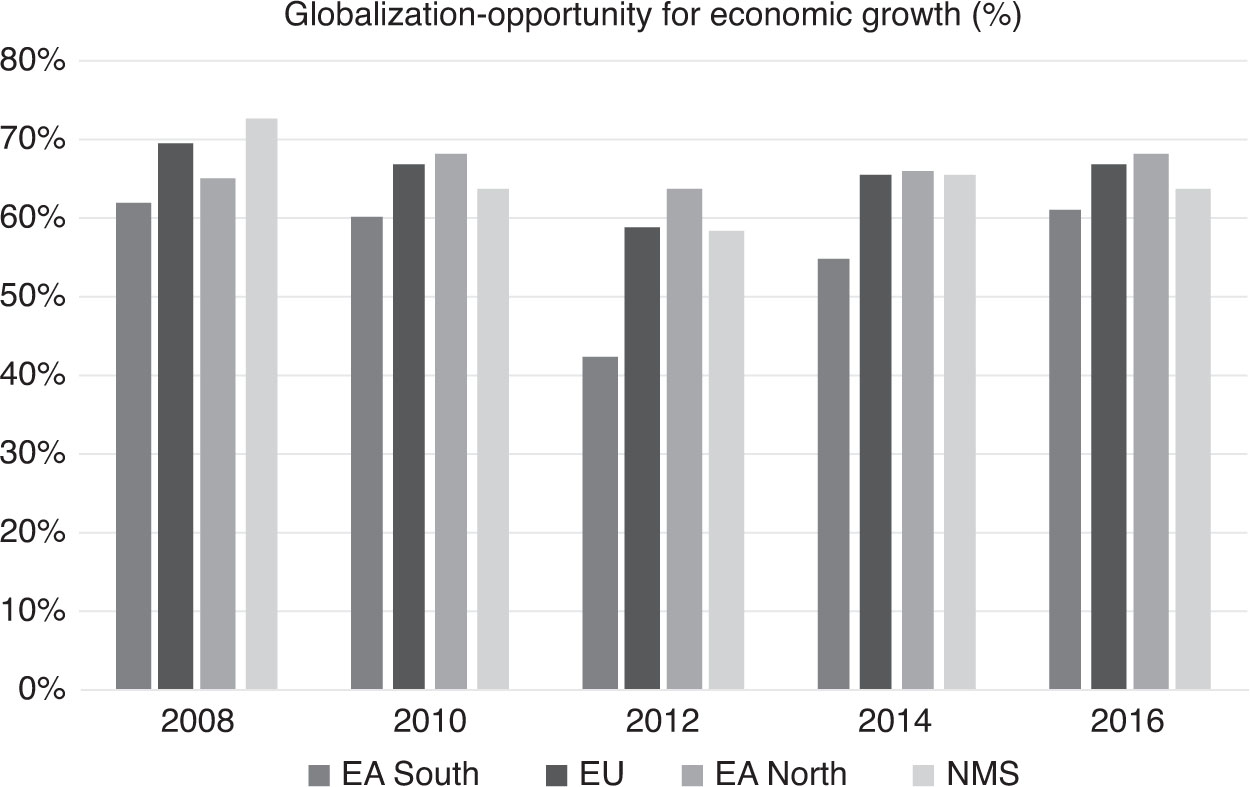

In recent years, few issues have been as controversial as globalization, or as politically salient. Overall, globalization is a complex phenomenon offering an opportunity for economic growth, but with potentially negative social implications that it is not straightforward to assess. This uncertainty is reflected in the difficulty of envisioning a response to the potentially negative consequences of globalization. Europeans’ assessment of globalization as an opportunity for economic growth is mixed (Batsaikhan and Darvas, 2017). At the European Union (EU) level, 70 per cent of respondents to the Euro-barometer survey stated that they strongly or at least somewhat agreed with the idea that globalization could be an opportunity for economic growth. The proportion dropped by more than ten points during the crisis, and has recently bounced back, although with significant differences across countries (Figure 4.1).

There is no lack of literature suggesting the EU has an important role to play vis-à-vis globalization. Buti and Pichelmann (2017) argue the process of EU integration has traditionally been conceived as a way to square ‘Dahrendorf’s quandary’1 between globalization as an opportunity for growth, social cohesion and political freedom, by allowing for catch-up economic growth and convergence while preserving Europe’s social models. Wallace (2000) argues that the impact of globalization in Europe has to be read through an experience of ‘Europeanization’. In Europe, efforts to manage cross-border connections are part of the historical experience and the geographical arrangement of the continent. This long history in turn produced a set of embedded features that shape European responses to cross-border connections. And the pattern of European responses exhibits certain specificities that make Europe as a region different from most other regions in the world. Europe has considerable capacity for collective engagement, but is diffusely managed depending on the issues being addressed. Wallace sees hard cooperation as achievable on political economy issues, and claims that Europeanization is sufficiently deeply embedded to act as a filter for globalization. Jacoby and Meunier (2010) argue that the advocacy of managed globalization – an approach that is neither ad hoc deregulation nor old-style economic protectionism – has been a primary driver of major EU’s policies in the past. Antoniades (2008) argues that economic globalization emerged in the EU as a debate on the nature and future of Europe. On the one hand, the EU was instrumental in bringing about the globalized post-Cold War economic order, by aggressively promoting the principles and policies upon which this economic order has been based. On the other hand, this proactive engagement was translated within the EU into a highly polarized and antagonistic public discourse that led to an identity crisis. After 2005, this discourse started to change due to the rise of flexicurity as a new way to think about Europe’s place and orientation in the global political economy. Bini Smaghi (2007) argues that EU citizens believe globalization is influenced far more by the EU than by national governments, which creates a ‘demand’ for more ‘Europe’ in the globalization process – to which Europe does not seem to be responding. In the light of this long-standing debate and the recent economic crisis, understanding what is driving Europeans’ economic assessment of globalization and what role they see for the EU can help to understand if the EU has been instrumental in squaring Dahrendorf’s quandary. It is also important from a policy perspective, because it constitutes a valuable background against which to evaluate recent EU economic and social initiatives.

FIGURE 4.1 European’s perception of globalization.

Source: Eurobarometer (69.2; 73.4; 78.1; 82.3; 86.2).

Europeans’ Attitudes towards Globalization

In this chapter, we investigate empirically how Europeans’ economic assessment of globalization is influenced by specific socio-economic characteristics, and whether these have changed with the crisis. We also look at how Europeans’ assessment of globalization is mediated through the conception that Europeans have of the role of the EU. To do so, we use two waves of opinion surveys (Eurobarometer) conducted regularly by the European Commission across all Member States – one wave before the crisis (2008) and one after (2013).2 The two Eurobarometer waves that we selected include questions that ask respondents to state their degree of agreement on selected statements about globalization. One of the questions asks whether respondents agree that ‘globalization is an opportunity for economic growth’:3

QUESTION (2008 wave): For each of the following statements, please tell me whether you strongly agree, somewhat agree, somewhat disagree or strongly disagree: ‘Globalization is an opportunity for economic growth’

1. Strongly agree

2. Somewhat agree

3. Somewhat disagree

4. Strongly disagree

5. DK

We use this question to construct a binary dependent variable that equals 1 if a respondent strongly or somewhat agreed with the statement that globalization is an opportunity for economic growth and 0 otherwise. This variable allows us to gauge the extent to which Europeans share the view that globalization has economic benefits to offer, and estimate how different factors affect the probability that respondents will express a positive view of globalization.4

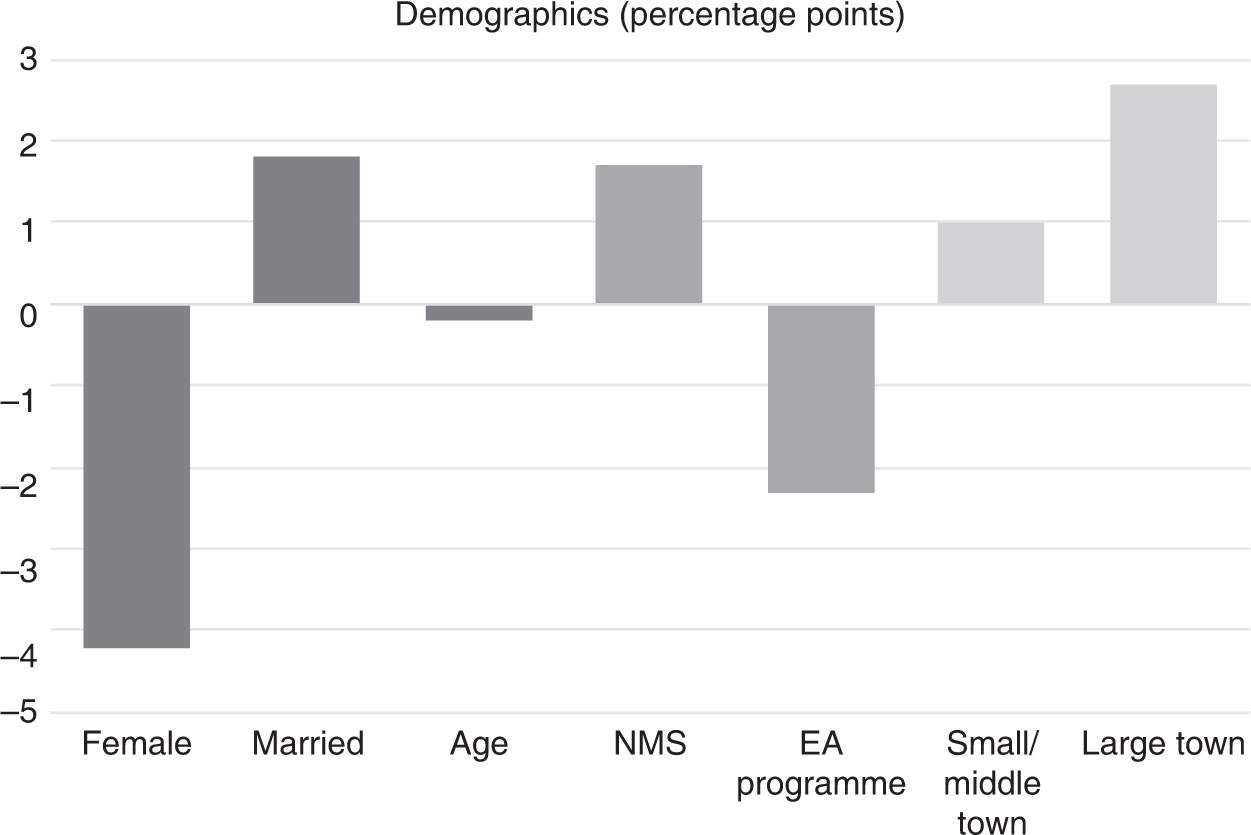

A first group of factors that we consider are characteristics of the respondents, such as their age, gender, marital status, what kind of community they live in (a rural area/village, a small city or a large city) and their level of education. We look at whether respondents are unemployed and whether they have experienced economic hardship.5 A second group of variables aims at capturing the respondents’ assessment of the national and European economic situation. In the two surveys that we use, interviewees were asked to state whether they considered the domestic situation of the economy or employment better or worse than the average in EU countries.6 Lastly, the Eurobarometer asks respondents to state what the EU ‘means to them personally’, and reports the number of individuals who answer with specific terms, which we use to investigate how Europeans’ view of the role of the EU is related to their perception of globalization.7 We also include specific controls for individuals in new member states and euro area countries that have been subject to the EU/IMF adjustment programmes, to understand whether they systematically differ in their assessment of globalization from the rest of the EU (Figure 4.2).

FIGURE 4.2 Demographics.

Source: Own estimates based on Eurobarometer (69.2; 73.4; 78.1; 82.3; 86.2).

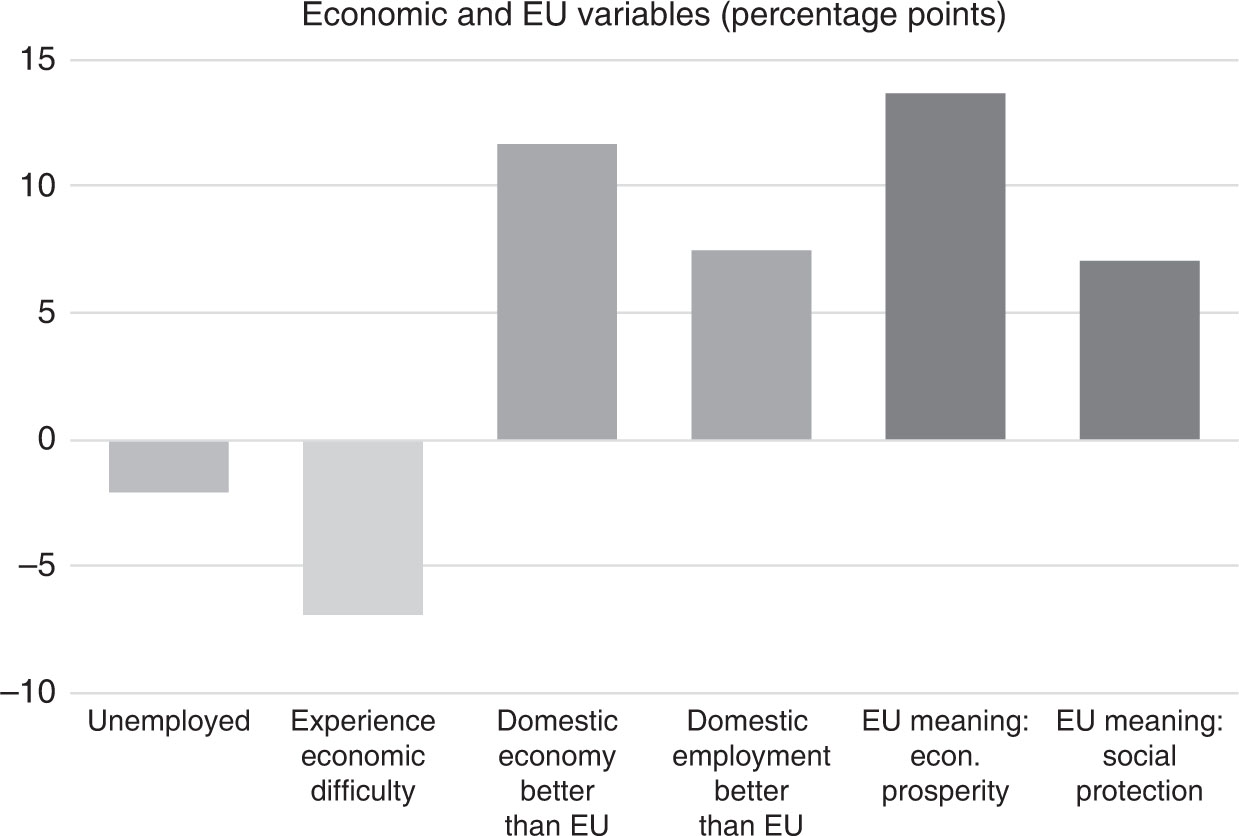

Demographic characteristics appear strongly correlated with respondents’ opinion about globalization as an opportunity for economic growth (Figure 4.2). Women appear more sceptical than men, as their probability of expressing a positive opinion is between 5.8 and 4.1 percentage points lower than for comparable men. Married individuals tend to hold a slightly more favourable opinion than comparable unmarried ones, and older respondents tend to be more sceptical, although the marginal effect is small. A negative time trend appears to exist between 2008 and 2013, suggesting that respondents’ assessment of globalization as an opportunity for economic growth deteriorated over time, most likely capturing the effect of the global financial crisis and the euro crisis. There also seem to exist differences across countries, with respondents in New Member States being more positive, and respondents in EA countries that experienced an EU/IMF adjustment programme being more negative, than respondents in the rest of the EU. Respondents’ views about globalization are unsurprisingly also influenced by the type of community they live in, which may be a proxy for the effect of exposure to a more (or less) cosmopolitan environment. Compared to respondents living in rural areas/villages, respondents living in large cities are consistently more likely to state that globalization is an opportunity for economic growth, while respondents living in small cities are still more positive than the rural group, but the effect is smaller (Figure 4.3).

Education is also an important factor whose effect seems to be non-linear. Respondents who left school when they were 14 years old are less likely to see globalization as an opportunity for economic growth than respondents with no full-time education, although the result is not statistically significant. From 16 years on, every additional year of education is associated with an increase in the probability of holding a positive view about the economic opportunities of globalization, but the strongest effect by far is among people with very high educational levels (20, 21 and 22 years) and among respondents who are still studying, probably capturing the positive effect of respondents’ younger age (Figure 4.3). Similar effects are found in Batsaikhan and Darvas (2017).

Respondents’ personal economic situation is also strongly and significantly correlated with their likelihood of perceiving globalization as an opportunity for economic growth. Unemployed respondents are between 2 and 3.8 percentage points less likely to answer positively than people who are employed, all else being equal. Respondents who have experienced economic difficulties – difficulties paying bills – are between 5.5 and 10.8 percentage points less likely to see globalization as an opportunity for economic growth than people who did not experience the same economic hardship, all else being equal (Figure 4.4).

Coming to the role of the EU, the perception of the domestic economy’s relative position with respect to the EU average is significant. Respondents who see the domestic economy as lagging behind the rest of the block are 10–12 percentage points less likely to see globalization as an opportunity for economic growth. Similarly, those who see the domestic employment situation as worse than the EU average are about 6.6–7.9 percentage points less likely to have a positive view of globalization. What the EU ‘means’ to respondents seem to matter for their view about the economic side of globalization. Those who see the EU as meaning ‘economic prosperity’ are nearly 14 percentage points more likely to see globalization as an opportunity for economic growth. The correlation is of 7–9 percentage points among those who see the EU as meaning ‘social protection’. These findings are not exceptional within the literature (Edwards 2006). Looking at 17 developed and developing countries, ‘values’ are a powerful explanation for variations in public opinion; they have more explanatory power than evaluations of the economy or partisanship, and roughly the same explanatory power as skill levels. Balestrini (2014) finds that citizens’ views of their country’s direction, the state of democracy, and whether EU membership is beneficial explain their attitudes towards globalization to a greater extent than education.

Policy Initiatives

The previous section highlighted some important features relating to Europeans’ perceptions of globalization. First, an individual’s economic situation (whether they are unemployed or experience difficulties paying bills) is an important factor, but national relative position in the EU seems to matter even more: people who see their country doing worse than the EU average in economic or employment terms are more sceptical in their assessment of globalization. Moreover, the perception of the EU’s role is very important: respondents to whom the EU ‘means’ economic prosperity and social protection are more likely to see globalization as an opportunity for economic growth. Since the financial and euro crisis, EU institutions and economic policies have been called into question. The EU is often portrayed as the promoter of a neo-liberal paradigm, blind to the social implications of its economic prescriptions. The need for change was acknowledged by the European Commission’s president, Jean-Claude Juncker, who, in his opening statement before the European Parliament plenary session, stressed the need to reverse the high rate of youth unemployment, poverty and loss of confidence in the European project. Buti and Pichelmann (2017) rightly point out that EU institutions and policies are prone to populist attack not only from this economic angle, but also from the perspective of identity, expressed as fear of European ‘homogenization’. They argue that the EU faces a difficult trade-off between more involvement in distributional issues, as the economic view of populism would prescribe, and less involvement in member-states’ affairs as the ‘identitarian’ view would imply. The EU created a European Globalization Adjustment Fund (EGF) in 2007 to co-fund policies to help workers negatively affected by globalization find new jobs. Claeys and Sapir (2018) provide an evaluation of the EGF and find the programme was politically high profile but its economic effectiveness is more difficult to evaluate – although estimates suggest only a small proportion of EU workers who lost their jobs because of globalization received EGF financing. More recent initiatives – such as the Juncker Investment Plan or the Youth Guarantee – can be read as an attempt to strike a balance between the perceived need for stronger EU involvement while avoiding ‘intruding’ into sensitive national competences.

Investment Plan

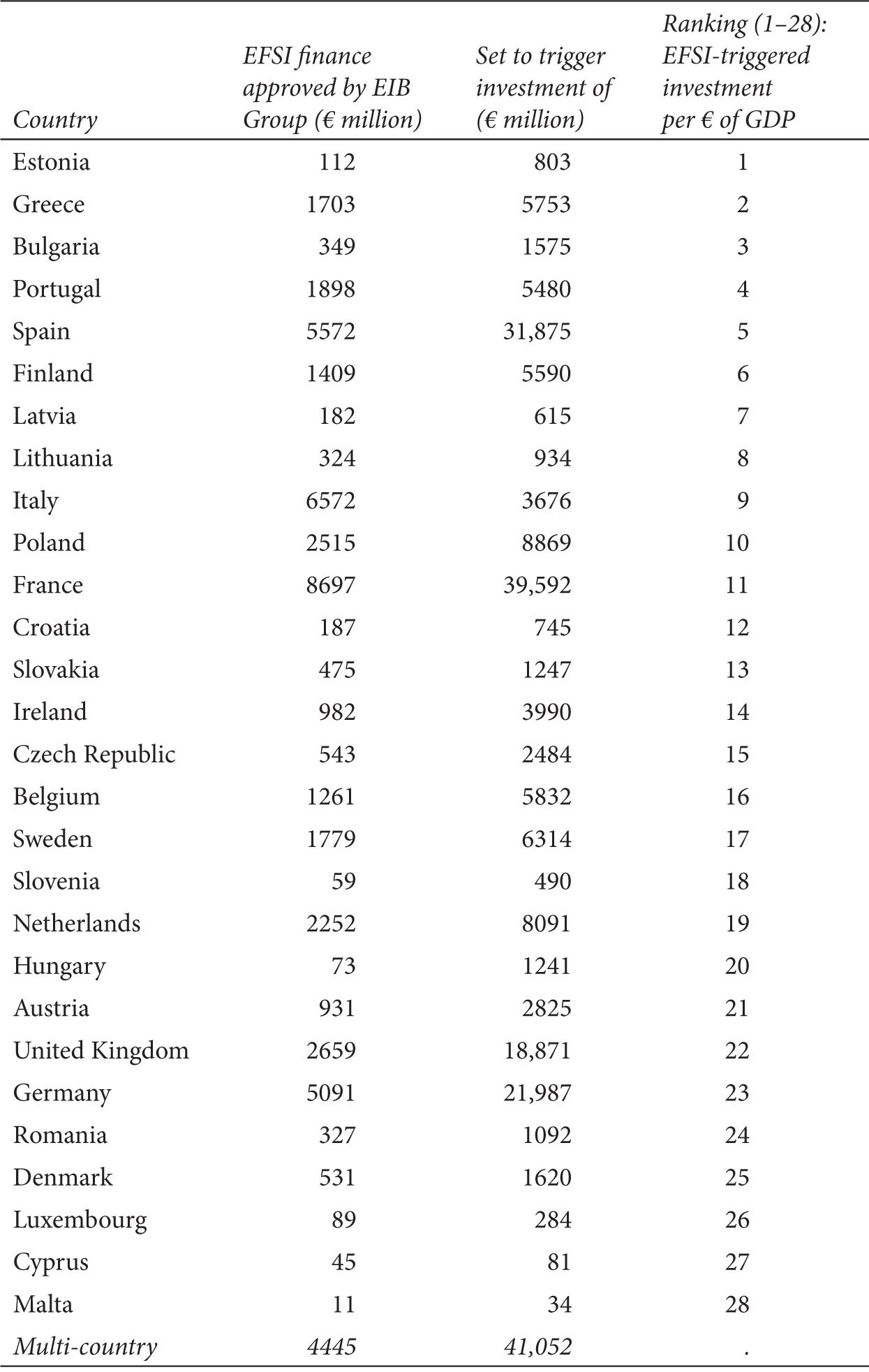

The Investment Plan for Europe (‘the Juncker Plan’) consists of three objectives: (i) remove obstacles to investment; (ii) provide visibility and technical assistance to investment projects; and (iii) make smarter use of financial resources. These objectives are served by three pillars. First, the European Fund for Strategic Investments (EFSI), which provides an EU guarantee to mobilize private investment and where the European Commission works together with the European Investment Bank (EIB). Second, the European Investment Advisory Hub and the European Investment Project Portal provide technical assistance and visibility of investment opportunities. Third, improving the business environment by removing regulatory barriers to investment both nationally and at the EU level. As of 12 December 20178 based on approved projects, 81 per cent of the 315€ billion target had been reached. Table 4.1 shows the ranking of countries in terms of the expected triggered investment in percentage of GDP, as well as the total EFSI financing.

EFSI is not geographically earmarked and according to the December 2017 data, all EU countries had been reached. However, the EU15 received about 89 per cent of all EFSI funding, whereas the rest of the EU received only 11 per cent (excluding multi-country operations). An external evaluation by Ernst and Young (2016) reports that reasons mentioned for lower EFSI support in Central and Eastern Europe are the competition from the European Structural and Investment Funds (ESIF), less capacity to develop large projects, less experience with Public Private Partnerships, a less developed Venture Capital market, and the small size of projects (Figure 4.5A and 4.5B).

One positive aspect – especially in light of the results in the previous section – is the fact that three of the top five recipients in terms of total investment as a percentage of GDP are countries that experienced EU/IMF macroeconomic adjustment programmes during the crisis (Greece, Portugal and Spain). In terms of sectors, energy and research-development-innovation have the largest number of projects, but investment in energy-related projects is by far the largest sector. There are also numerous multi-sector projects, which receive a sizable share of investment. The key question is whether the projects financed through EFSI are really additional that is, projects that would never be financed otherwise. On this, there are some sceptical views. Claeys and Leandro (2016) look at similarity of EFSI and regular EIB projects and find only one out of 55 projects for which no similar EIB standard project exits. Ernst and Young (2016) find that respondents to surveys and interviews indicated that some of the financed projects could have been financed without EFSI support, meaning that these investments could be interpreted as not being fully additional (although the perception is not homogeneous).

Youth Guarantee

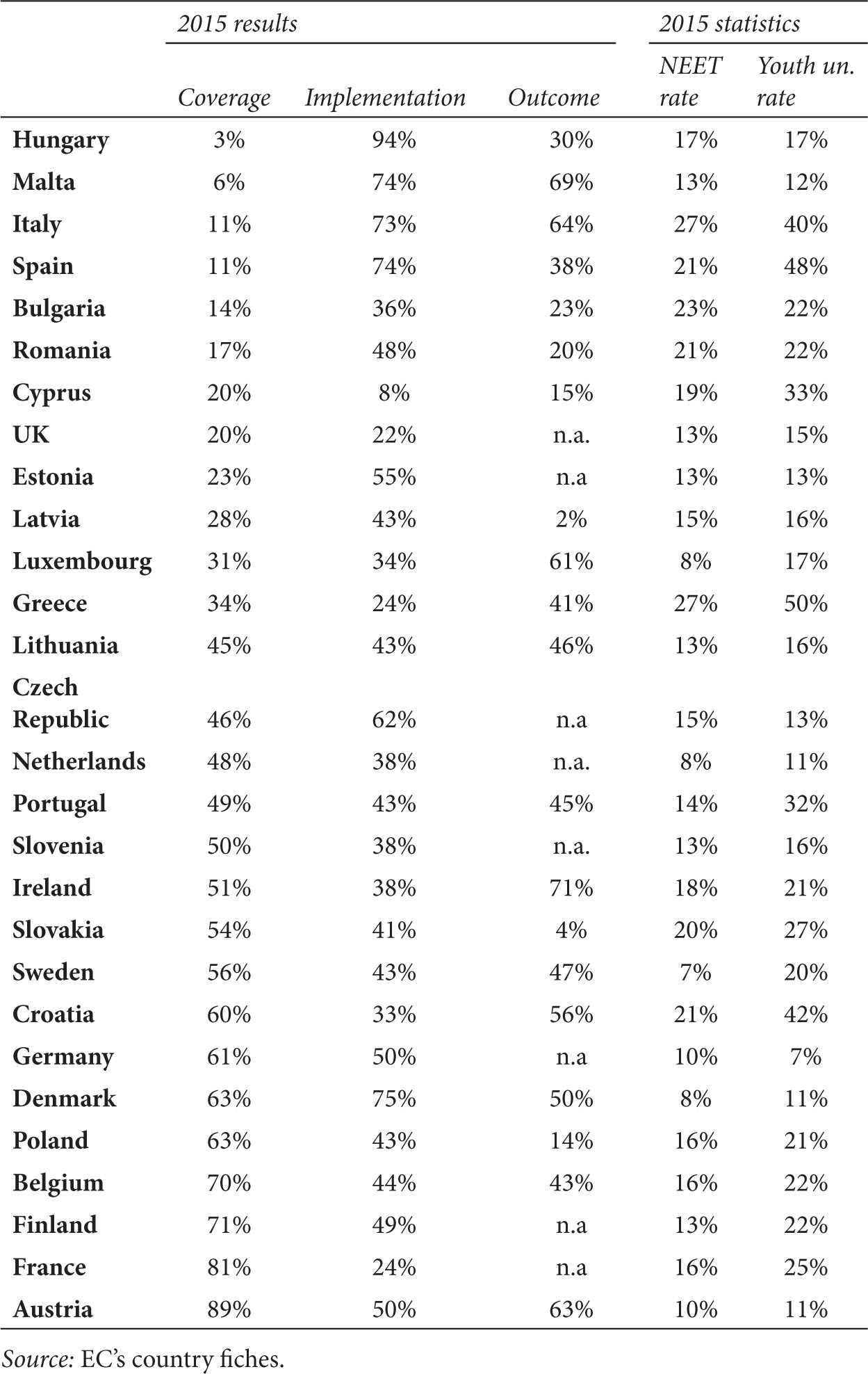

The rise of youth unemployment has certainly been one of the most visible effects of the euro crisis. The Youth Guarantee is a commitment by Member States to ensure all those under the age of 25 years receive a good quality offer of employment, continued education, apprenticeship or a traineeship within four months of leaving formal education or becoming unemployed. The Youth Employment Initiative (YEI) is one of the financial instruments launched to support the guarantee, and provides support to young people living in regions where youth unemployment was higher than 25 per cent in 2012 – it was subsequently topped up in 2017 for regions with youth unemployment higher than 25 per cent in 2016. The total budget of the Youth Employment Initiative is €8.8 billion for 2014–20 – increased in 2017 from an initial €6.4 billion. Youth unemployment has been going down since 2015, but the key question is how much this is due to cyclical factors, as opposed to policy action. The most recently available country-level data on the implementation of the Youth Guarantee (as of 2015) are reported in Table 4.2. Coverage – i.e. the percentage of young people not in education, employment or training (NEET) – tends to be low (less than 50 per cent in 16 out of 28 countries) and implementation – i.e. the take-up of an offer within four months – is also below 50 per cent in 18 out of 28 countries. A special report of the European Court of Auditors, released in April 2017, looks in depth at Ireland, Spain, France, Croatia, Italy, Portugal and Slovakia and concludes that implementation is lagging behind. The ECA point out it seems not to be possible to address the whole NEET population with the resources available from the EU budget alone, and that the YEI gave very limited contributions to the achievement of the Youth Guarantee’s objectives.

FIGURE 4.5A EFSI statistics.

FIGURE 4.5B EFSI statistics.

Note: Including approved and signed projects; amounts for some projects are not disclosed

TABLE 4.2 Youth Guarantee across EU countries

Conclusion

Few issues have been as controversial and as politically salient in recent years as globalization. Opinions differ as to the link between globalization and inequality on one hand and growth on the other. Mirroring these differences, there is no more clarity on the policy side as to how the so-called ‘losers’ of globalization should be compensated. In Europe, there is a long-standing conception of EU integration as a way to square the circle between globalization, social cohesion and political freedom. Advocacy of managed globalization has been identified in the past as a primary driver of major EU policies. Since the financial and euro crisis, however, EU institutions and economic policies have been increasingly called into question. The EU is portrayed as the promoter of a neo-liberal paradigm, blind to the social implications of its economic prescriptions by Eurosceptic parties that often advocate forms of protectionism. The need for change was acknowledged by European Commission’s President Jean-Claude Juncker who, in his opening statement before the European Parliament plenary session, stressed the need to reverse the high rate of youth unemployment, poverty and loss of confidence in the European project. The data analysed in this chapter highlights that economic factors, both at the individual and country level, are important to understand Europeans’ economic assessment of globalization. Interestingly, individual economic indicators – such as personal unemployment or economic difficulties – matter, but they matter less than people’s assessment of their countries’ economic position vis-à-vis the EU average. This emphasizes one additional reason why fostering income convergence across the EU is important.

Whether this is still possible after the crisis of last decade is a legitimate question. But the rise of Euroscepticism that we have witnessed in national elections testifies to the importance of this objective. Besides economic factors, the perception of the EU as an avenue of economic prosperity and social protection is important, with people who associate the EU with these features displaying a more positive view of globalization as an opportunity for economic growth. This highlights the importance of EU action and it seems to have been acknowledged by EU policy-makers themselves, as mirrored in the Juncker Agenda. To date, however, the results of flagship initiatives are mixed. The European Globalization Fund seems to be improvable, potentially in terms of its scope, which could be enlarged beyond globalization to assist workers displaced by intra-EU trade and off-shoring that result from the working of the single market (see Claeys and Sapir 2018). While the EU investment plan is clearly advancing – although with mixed reviews when it comes to the additionality of the projects financed with EFSI funds – the Youth Guarantee seem to be far from achieving its targets. While these are steps in the right direction, the EU does not yet appear to have succeeded in squaring the Dahrendorf challenge, establishing itself as a successful mediator between its citizens and the challenges of globalization.

Notes

1. Dahrendorf (1995) argued that to stay competitive in a growing world economy, countries would be obliged to adopt measures that could inflict irreparable damage on the cohesion of the respective civil societies, or to implement restrictions of civil liberties and of political participation.

2. Details about the survey are available at http://www.gesis.org/eurobarometer-data-service/survey-series/standard-special-eb/sampling-and-fieldwork/. The data was downloaded from GESIS’ archives. We use wave EB 69.2 in 2008 and EB 79.3 in 2013. This is because while almost all waves of the survey include the basic attitudinal questions on globalization that we use to construct our dependent variable, only few waves include some of the questions that we rely on for constructing independent variables.

3. The answering options are worded slightly differently in the 2013 wave, where instead of ‘strongly agree/disagree’ the answer states ‘totally agree/disagree’ and instead of ‘somewhat agree/disagree’ we have ‘tend to agree/disagree’. Overall, however, they are comparable.

4. By running a Logit model of our dependent variable on six incremental sets of independent variables. Our dataset is a pooled cross-section of 52,355 observations from Eurobarometer over two years (2008 and 2013).

5. This is defined as someone declaring that they experienced ‘difficulties paying bills’ either most of the times or from time to time.

6. We construct dummy variables equalling 1 for those who answered they saw the domestic situation as either ‘much better’ or ‘somewhat better’, which will help us capture the effect of perceived relative positioning within the EU.

7. We construct a dummy variable equal to 1 for those people who mentioned ‘economic prosperity’, another dummy equalling 1 for those who mentioned ‘social protection’ and a third dummy equal to 1 for those mentioning ‘unemployment’. On top of these variables, we sometime include country dummies, or area dummies identifying new member states and euro area countries that have been subject to the EU/IMF adjustment programmes.

8. See http://www.eib.org/efsi/efsi_dashboard_en.jpg.

References

Antoniades, A. ‘Social Europe and/or global Europe? Globalization and flexicurity as debates on the future of Europe’, Cambridge Review of International Affairs 21(3) (2008).

Balestrini, P. P. ‘Public opinion regarding globalization: The kernels of a “European Spring” of public discontent?’ Globalizations 12(2) (2015) pp. 261–75.

Batsaikhan, U. and Z. Darvas. ‘Europeans rediscover enthusiasm for globalization’, Bruegel blog (2017).

Bhagwati, J. In Defense of Globalization (Oxford, Oxford University Press 2004).

Bini Smaghi, L. ‘Globalization and public perceptions’, Dinner speech by Lorenzo Bini Smaghi, Member of the Executive Board of the ECB at the joint meeting of the GEPA-GPA-GSPA (2007).

Bourguignon, F. The Globalization of Inequality (Princeton, Princeton University Press 2015).

Buti, M. and Pichelmann, K. ‘European integration and populism: addressing Dahrendorf’s quandary’, LUISS Policy Brief (January 2017).

Claeys, G. and A. Sapir ‘The European globalization adjustment fund: Easing the pain from trade?’, Bruegel Policy Contribution, Issue 5 (2018).

Collier, P. The Bottom Billion: Why the Poorest Countries are Failing and What Can Be Done About It (Oxford, Oxford University Press 2007).

Dahrendorf, R. ‘Economic Opportunity, Civil Society and Political Liberty’, UNRISD Discussion Paper 58, Geneva (March 1995).

Dollar, D. ‘Globalization, poverty, and inequality’ in Weinstein (ed.) Globalization: What’s New? (New York, Columbia University Press 2005) pp. 96–128.

Edwards, M. S. ‘Public opinion regarding economic and cultural globalization: Evidence from a cross-national survey’, Review of International Political Economy 13(4) (2006) pp. 587–608.

European Court of Auditors ‘Special report No 5/2017: Youth unemployment – have EU policies made a difference?’ (2017). Available on ECA’s website at: https://www.eca.europa.eu/en/Pages/DocItem.aspx?did=41096 (Accessed 16 July 2018).

Ernst and Young. ‘Ad-hoc audit of the application of the Regulation 2015/1017 (the EFSI Regulation)’, Final report (14 November 2016). Available on the EC’s website at: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/sites/beta-political/files/ey-report-on-efsi_en.pdf (Accessed 16 July 2018).

Jacoby, W. and S. Meunier. ‘Europe and the management of globalization’, Journal of European Public Policy 17(3), (2010) pp. 299–317.

Merler, S. Convergence in Europe: arrested development? (Council for European Studies, Columbia University, 14 July 2016). Available at https://ces.confex.com/ces/2017/webprogram/Paper16319.html (Accessed 20 July 2018).

Rajan, R. G. Fault Lines: How Hidden Fractures Still Threaten the World Economy (Princeton, Princeton University Press 2010).

Sapir, A. ‘Globalization and the reform of European social models’, Journal of Common Market Studies 44(2) (2006) pp. 369–90.

Wallace, H. ‘Europeanization and globalization: Complementary or contradictory trends?’ New Political Economy 5(3) (2000) pp. 369–82.

Weinstein (ed.) Globalization: What’s New? (New York, Columbia University Press 2005).