Social Democracy in an Era of Automation and Globalization

Jane Gingrich

The last years have not been kind to social democratic parties. The political earthquake election of Donald Trump in the United States, the British Brexit vote, and rising populism across Europe are the most recent manifestations of a longer-term unsettling of traditional political alignments, an unsettling that has cost social democratic parties almost everywhere. In the European national elections of 2017, only in Norway did the Social Democrats maintain power (with a smaller vote share); in the French presidential election, the first-round vote share of the Socialist Party candidate fell from 29.4 per cent in 2012 to 7.4 per cent; the German Social Democrats fell from an already depleted 25.7 per cent to 20.5 per cent of votes; while the Dutch Labour party sunk from 24.8 per cent in 2012 to 5.7 per cent. British Labour, which increased its vote share in 2017, forms a notable exception, albeit not a victorious one.

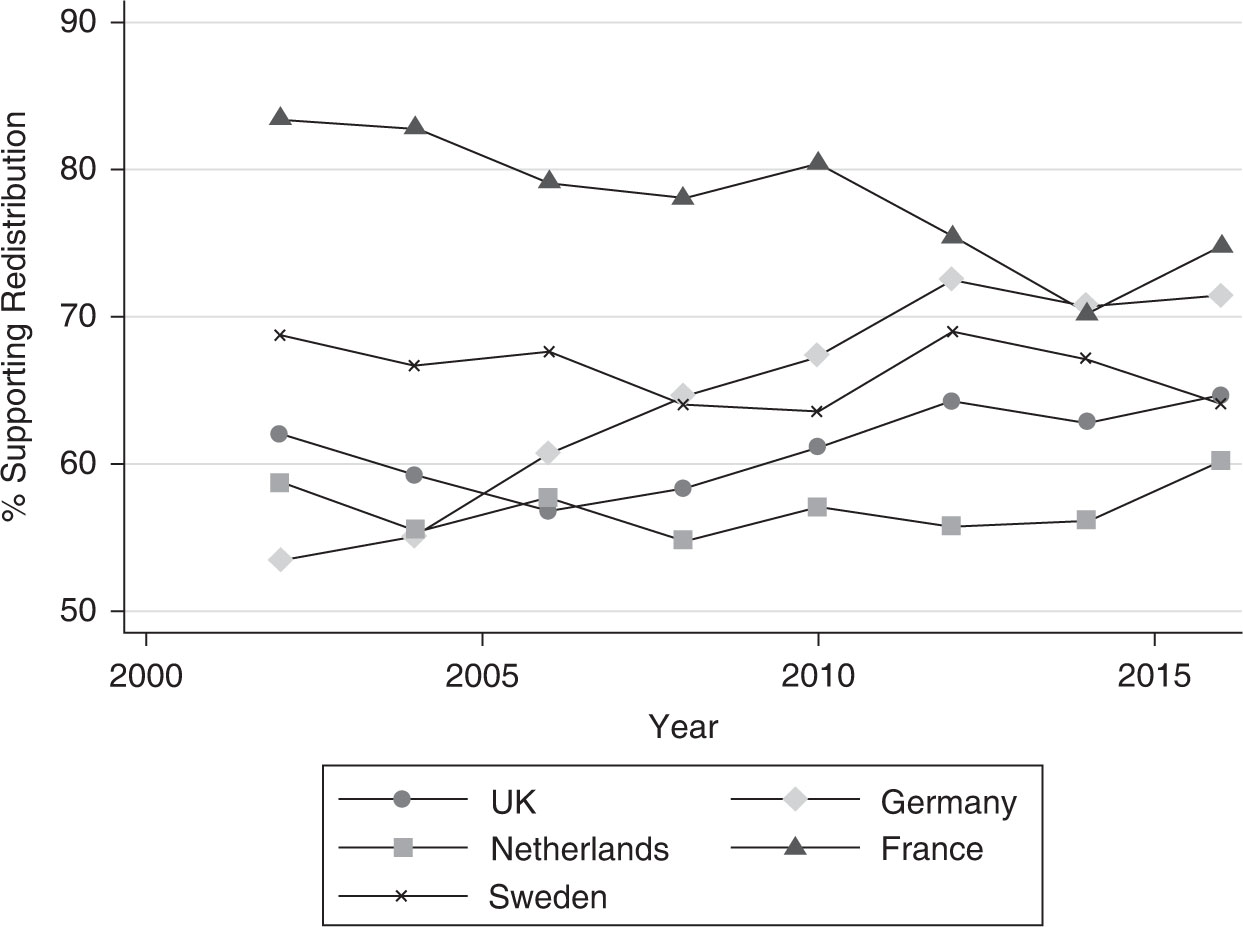

This electoral decline of social democratic parties comes at a time when many of their core values remain both economically and politically viable, and indeed, are in ascendency in some contexts. Employers and mainstream economists have, in some cases, called for more (not less) investment in skills and infrastructure (e.g. Heckman 2011), and recent work by the OECD and International Monetary Fund (Cingano 2014; Ostry 2014) has pointed to the deleterious consequences of inequality on long-run growth. Voters, too, support an active state. Figure 13.1 displays public opinion data from five European nations taken from the European Social Survey (2016), and shows that in all cases, a majority of citizens report to support income redistribution, and in most cases, average support has risen over the last decade. Why has the mainstream left not captured more of this basic support for left-wing economic policy? Can it reverse this changing tide?

This paper follows much work in political science to argue that the left’s woes are in part due to structural changes in the economy that have both created economic challenges and altered the social bases of the left’s electoral support. The following pages focus on these economic policy changes, although other policy dilemmas, such as those around immigration, cultural liberalism, and nationalism are also relevant.

FIGURE 13.1 Public support for redistribution in five EU countries.

In focusing on economic change, this paper argues that structural pressures manifest through a series of policy challenges that individually the mainstream left is well placed to address, but that collectively, it has faced more difficulty in reconciling. The changing structure of labour markets has meant that left parties concerned with inequality and poverty have faced the simultaneous policy challenge of expanding skills among workers and attracting ‘good’ jobs to changing local labour markets while also continuing to address the needs of their traditional constituencies, many of whom have been displaced (directly or indirectly) by economic change. At the same, social democratic parties have faced a very different electoral environment, as the class structure has radically changed (Oesch 2016).

The challenge of addressing individual and geographic vulnerability in post-industrial labour markets and maintaining traditional vote share have often pulled in different directions, with left parties either prioritising policies that create more economically competitive citizens and regions, without the political visibility or stability of past appeals, or maintaining traditional class and community support without longer term policies able to address economic change.

The paper outlines these challenges, and then suggests some lessons for moving forward.

The Post-Industrial Challenge: Skills and Communities

In examining the turbulent fortunes of left parties in the post-financial crisis era, scholars and pundits alike have pointed to the deeper economic and political roots of social democratic decline (e.g. Beramendi et al. 2015). Both global economic integration and the automation of many manufacturing jobs have altered the economic structure of advanced industrial economies, radically reshaping the types of skills demanded in many labour markets. Through the 1980s and 1990s, many labour economists pointed to the growing compatibility between new technologies and higher levels of general skills (e.g. university degrees), meaning that the economic returns to higher-skilled work have grown (Goldin and Katz 2009; Berman and Machin 2000). This shift hit those in mid-skilled ‘routinisable’ jobs particularly hard, with declining employment in traditional industrial jobs as well as many types of clerical work (Autor et al. 2003; Goos and Manning 2007). As industrial jobs disappeared, newly created jobs often required either higher levels of skills or lower levels of pay.

These structural changes in the labour market have created new policy challenges in addressing individual level risk and vulnerability. While scholars debate the relative contribution of technology, globalization and other factors to growing inequality, there is no doubt that across most advanced industrial economies income inequality has risen since the 1980s, and low-skilled individuals are bearing the brunt of these shifts. In many contexts, relative increases in the wages of low-skilled citizens have lagged behind their higher-skilled counterparts – even as the size of the high-skilled workforce has expanded – and in the post-financial crisis period low-skilled citizens have been hit particularly hard (OECD 2014). Some workers have lost jobs, but perhaps more importantly, new cohorts of low-and mid-skilled workers have faced difficulty finding work, or finding high quality work.

The disappearance of industrial jobs and rise of new service sector work has not only created new categories of vulnerable workers but also vulnerable geographic regions. Post-industrial labour markets have often privileged more concentrated urban areas (Moretti 2012), placing pressure on declining industrial regions. These geographic shifts have meant that entire places, as well as workers with particular types of skills, have faced tough economic adjustment.

FIGURE 13.2 EU relative employment loss in manufacturing 1991–2014.

Since 1991, all 15 European Union (EU) countries have lost employment in manufacturing, but this loss affected some regions more than others. Figure 13.2 shows a scatter plot of relative employment loss in manufacturing between 1991 and 2014, and the percentage of local employment in manufacturing in 1991 in UK, France and Germany.1 Figure 13.2 illustrates substantial variation in regional experiences. Some regions have been harder hit by industrial decline than others, with the industrial regions of the UK, for instance, losing more jobs than their counterparts in Germany. Equally, the adjustment path has varied even in regions with similar levels of decline; some have faced higher rates of unemployment than others; French regions, for instance, face higher long-run levels of unemployment than their similarly affected British counterparts (Eurostat 2016).2

Maintaining living standards in regions where upwards of half of industrial jobs have disappeared, or where there is persistently high unemployment, can be challenging. Even those regions that have avoided high levels of unemployment, such as the industrial regions of the UK, have faced difficult economic adjustment. Figure 13.3 shows the tremendous variation within and across European countries in productivity levels, as demonstrated by the map of gross value added per capita across European regions in 2014. This regional variation matters for policy-makers concerned with equity in living standards within a country.

FIGURE 13.3 GVA per capita across Europe’s regions in 2014.

Why do these changes matter for the left? At first glance, new post-industrial pressures offer opportunities for left parties, as economically left policies are often compatible with improved economic performance. In the long-run, many argue that public investment in skills is likely to be growth producing (Krueger and Lindahl 2001). Moreover, as job creation in declining regions is often anaemic, with labour mobility not offsetting the decline, some argue that public investment in the infrastructure of deindustrialising regions can improve productivity. For instance, a recent working paper by economists Anna Valero and John van Reenan (2016) suggests that the expansion of universities in an area can enhance regional growth. Put differently, public investment in both skills and local job creation can boost long-run growth above and beyond a laissez-faire minimalist approach. There is a seeming economic and equity ‘win-win’ to certain kinds of public spending, as investment in both skills, and physical infrastructure that diffuses skills and technologies to a broader set of citizens and communities, promises to be growth- and equity-producing.

This congruence between economic adjustment and left policy goals has not gone unnoticed in either policy or academic circles. Indeed, work on the political economy of post-industrial transition has pointed to the potential complementarity between economic growth and expanded equity by investing in the supply side of the economy (Boix 1998). However, this shift to the supply side and the ‘win-win’ scenario for the left has faced two major challenges in practice.

First, while expanding education and skills, and regional infrastructure is potentially equity creating in the long-run, in the short-run, maintaining equity still requires some conventional income security programmes to address economic dislocation. Addressing the vulnerabilities of lower-skilled workers, or mid-skilled workers employed in newly created lower-skilled jobs, and of local labour markets facing decline, often requires both new types of policies – investments in skills, training, education and active labour market policy – while also maintaining many traditional policies (e.g. pensions, unemployment insurance) and public service investment to compensate individuals and communities hit by economic change.

Spending on education and skills, while also investing in public infrastructure, and providing security to those hardest hit by economic changes, proved, in many cases to be beyond the capacity (or some might argue, the political will) of many left-wing governments, leading some to prioritize new spending over income security, while others attempted to slow the pace of economic adjustment while maintaining compensatory spending. I will argue below that these choices created tough trade-offs.

Second, next to these economic challenges, the voting base of the left has changed, and the new ‘win-win’ economic and equity creating policies often did not create durable ‘wins’ at the ballot box.3 Early work by Herbert Kitschelt (1994) and others, pointed to the growing gap between more culturally-oriented left voters and more traditional economic constituencies. As the manual working class has declined in numbers, and new urban service-oriented workers (both low and high skilled) have increased, the electoral base of left support has radically changed (Gingrich and Hausermann 2015; Gingrich 2017). However, for left parties, swapping industrial workers for the new urban service sector workers often meant moving from relatively developed organizational structures linked to trade-unions and local party affiliates to both less developed structures of mobilization and less attached voters.

These changes have, in many countries, meant that traditional left voters have shrunk in number, while newer voters are more willing to switch among left and centrist parties. With weaker links to organized labour, social democratic parties have increasingly relied on policy appeals and issues of competence to attract voters. However, as mentioned above, their policies have often been constrained, and policies alone have often not been enough to create secure centre-left voting blocs.

Social democrats then have faced a triple challenge: to address the real vulnerabilities and fallout created by structural economic change; to support dynamic and inclusive labour market adjustment both for individuals and regions; and to maintain vote share. The following sections suggest that parties often favoured one or two of these goals over others, struggling to combine all three. The final section returns to the possibilities inherent in the current moment, suggesting that aspects of left policy remain popular, are often economically efficient, and more equitable than the alternatives.

Social Democracy Constrained

In an early study of the challenge of addressing post-industrial economic adjustment, political scientists Torben Iversen and Anne Wren (1998) pointed to what they called the ‘trilemma’ of the transition to the service economy. Iversen and Wren argued that as productivity growth was slower in services than in manufacturing, the transition to a service based economy threatened to create new income equality by driving a wedge between the returns to those in productive industrial jobs and lower productivity service jobs. Governments could address this inequality by employing service workers in the public sector, a strategy that came at a cost of budgetary restraint, or by limiting service job growth, a strategy that threatened higher levels of unemployment. For Iversen and Wren, there was an inherent three-way trade-off among budgetary control, lower unemployment, and inequality, of which, at most two were achievable. Iversen and Wren argued that the Anglo-American countries were largely accepting higher levels of inequality, while the Continental European countries opted for higher unemployment, whereas the Scandinavian countries opted for greater public spending.

The development of the service sector has proven complex, as have national responses to it, but nonetheless, Iversen and Wren’s initial insight that trade-offs exist in how national political economies approached deindustrialization remains crucial. These differences have had important implications for the way social democratic parties have adjusted.

The Anglo-Approach – Visible Skills and Technocratic Redistribution

For both the United States and the UK, the experience of the 1980s and 1990s was of a more direct market-oriented approach to changing industrial structures, which produced, particularly in the case of the UK under the Conservative Thatcher governments, a sharp and prolonged shock to the manufacturing sector with rising income inequality through the 1980s. Similar patterns, albeit to differing extents, occurred through the Anglo world.

While the nature of political control varied across the Anglo countries, by the mid-1990s, many left parties were looking to reorient their appeal in the face of both electoral decline and the changing economic structure. Social democrats (or their mainstream left equivalents) in these countries faced the challenge of attracting new middle-class voters while also addressing the needs of traditional constituents in the face of rising inequality and stagnating wages.

In response, both in the United States and UK, and to a lesser extent elsewhere, mainstream left parties adopted a ‘third way’ mantra, ostensibly promising to make the market work better for all. The solution to squaring middle-class votes with more equity in the economy lay in supporting the development of individual skills, access to the labour market, and greater individual responsibility (Giddens 2013).

This approach generally accepted the inevitability of structural economic change – both globalization and automation – and eschewed policies to limit or blunt the pace of change. Moreover, instead of emphasising more traditional welfare programmes and public management to compensate for economic changes, Third Way left parties promised to achieve more equity by supporting the development of better jobs for a wider group of citizens. In so doing, Third Way politicians focused in particular on labour markets, promising to ‘make work pay’, while limiting – rhetorically – more traditional passive forms of redistribution such as cash transfers to the unemployed.

The key to do doing so involved investment in skills and the expansion of work opportunities. Most prominently, this approach involved the expansion of more general skills. In the UK, New Labour staked much effort on expanding the quality of schooling and the number of pupils leaving school with basic qualifications, while also expanding access to universities and higher education. Between 2000 and 2015, the percentage of the 25–64-year population with tertiary (university) education, expanded from 25 per cent to 45 per cent in UK, 22 per cent to 44 per cent in Ireland, 27 per cent to 44 per cent in Australia, and 40 per cent to 56 per cent in Canada. The United States, which started with a higher baseline expanded less, from 36 per cent to 45 per cent (OECD 2016).4

While much has been written on the ‘neo-liberal’ turn in the left, it is worth pointing out that third way policies did have a strong statist element to them. In the UK, the Blair and Brown governments substantially increased spending and central managerialism (Chote et al. 2010), while American Democrats pushed hard for both new health programmes and expanded regulation around education.

However, even as third-way left parties through the 1990s and 2000s called for, to quote New Labour, ‘education, education, education’, left parties recognized that a long-run investment in skills alone was not sufficient: addressing poverty, inequality, and vulnerability also required current spending on workers and other vulnerable groups such as children and the elderly. The result was that the left tended to combine an emphasis on skills and public services with a more technocratic approach to redistribution.

Technocratic redistribution, here, refers to the use of lower visibility and less overt forms of government spending, such as tax credits to support work or benefits targeted to families with children, rather than traditional spending programmes such as unemployment benefits. Through the 1990s and 2000s, both under left and non-left governments, in many Anglo countries, the real value of unemployment benefits fell. At the same time, however, most of these countries, often under left control, expanded alternative forms of income support. In the United States, alongside the welfare reforms of the 1990s (supported by both Democratic President Clinton and the Republican Congress), the expansion of tax credits for low income families with a worker became a central tranche of income support. In the UK, New Labour also expanded tax credits to families, as well as child benefits, cutting child poverty. Combined, these shifts meant a move towards less income support for the childless adults (pensioners have fared better), but more income support for families, particularly low-income families.

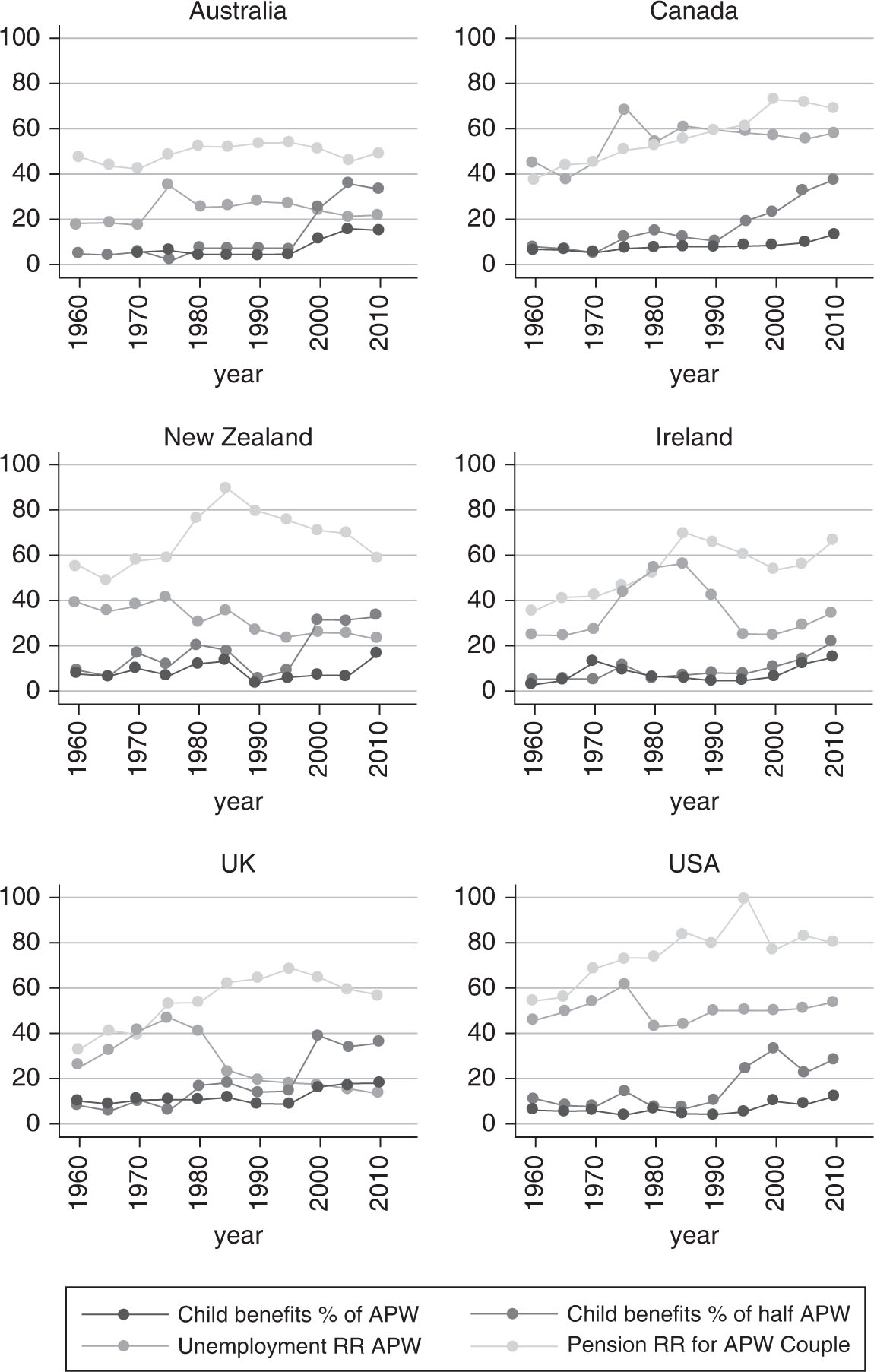

Figure 13.4 combines data on unemployment and pension replacement rates – the amount of income the average worker might anticipate during a spell of unemployment/during retirement as a percentage of the wages of a ‘standard’ worker in manufacturing – and child benefits as a percentage of average wages and low-earners’ (half of average) wages. What Figure 13.4 shows is that across the Anglo countries, child benefits, particularly for low-income working age adults, became increasingly important, even as unemployment benefit rates fell.5 Traditional income support programmes did indeed change, but the state continued to play a crucial role in redistributing resources and reducing poverty.

FIGURE 13.4 Income support programmes in major industrialized countries.

Technocratic approaches were often a reaction to a political moment in which many voters were less sympathetic to redistribution, and in particular, more passive redistribution (Cavaille and Trump 2015). However, technocratic redistribution often meant the individuals and communities who received it felt less vested in the system, and often more beleaguered, than past voters linked to organized labour or more visible benefits. As Geoff Evans and James Tilley (2012) show in the UK, working class voters (and other groups) increasingly saw little difference among political parties, despite the large increase in spending and reduction in poverty under Labour. By contrast, middle class urban voters supporting education and skills are increasingly quite securely linked to left policies, but not necessarily a given party.

In sum, while the expansion of educational access and the shift in the distributive structure of benefits had important effects, these policies in the short-run left much of the underlying market structure in place – low wage and low-productivity jobs remained a key part of the political economy, as did uneven geographic patterns of growth. At the same time, unlike earlier policies, such as building the NHS in the UK, or the New Deal in the United States, third way policies created fewer direct vested interests or mobilized voters linked to left parties themselves. The result was a less durable coalition around parts of the welfare state than the past, making parts of it more vulnerable, and political support more ephemeral.

Continental Path – Compensation and Liberalization

Social democratic parties in many Continental European countries were initially more reticent about cuts to traditional welfare programmes and less supportive of expanding higher general skills than their Anglo counterparts. However, as the costs of this approach – both politically and economically grew – many of these parties did move to a more reformist position, often with serious electoral consequences.

The extent of de-industrialization has varied substantially across the European continent, with some regions, particularly in Germany, retaining a strong industrial base. However, as elsewhere, both automation and globalization have put pressure on these labour markets.

During the 1980s and the 1990s, unlike in Britain, many Continental countries moved to slow the pace of change, and ease the burdens on workers. Oftentimes, this approach involved the expansion of benefits, particularly early retirement and disability benefits, to would-be displaced workers. Through the 1990s, labour force participation of older men fell, in 1995, across the EU-15 countries, only 39 per cent of men aged 55–64 were still active in the labour force, ranging from a high of 68 per cent in Sweden, to a low of 24 per cent in Belgium (European Commission 1996).

The expansion of access to early retirement often drew on cross-party policy, or collectively bargained benefits, and was not specific to social democratic parties (e.g. see Hemerijk and Visser 1997 on the Netherlands), yet these moves put social democratic parties in a particular bind. David Rueda (2005) has characterized this bind in terms of a conflict between social democratic constituents with secure jobs and benefits and younger cohorts of workers outside of this system. Initially, many social democratic parties found it hard to take the Anglo path. Their constituents in the manufacturing sector and unions resisted moves to liberalize labour markets or cut traditional unemployment and pension benefits, and for fiscal and political reasons new expenditure on active labour market policy in addition to existing benefits was seen as infeasible. The result was through the 1990s, in both Continental and Southern Europe, older industrial workers, and to a lesser extent the communities they inhabited, maintained both greater protection from structural change and compensation for it, but younger workers often faced new insecurities in finding permanent high-quality employment.

In response, in some contexts, social democrats began to reconsider their compensatory approach. In the Netherlands, the Dutch Labour party in the early to mid-1990s, moved towards supporting more labour market flexibility, with support for skills and active labour market policy. In Germany, the SPD-led Schroeder government also adopted a ‘third way’ rhetoric, which preceded a fairly substantial liberalization of the labour market for temporary employment, and cuts to some traditional benefits like unemployment insurance.

It is outside the bounds of this paper to evaluate the economic efficacy of these changes, but politically, they put social democrats in a difficult position, as these policies were not well received by the traditional voting base, and at the same time, did not create stable support elsewhere. Hanna Schwander and Philip Manow (2017), writing about the cuts and liberalization introduced by the SPD in Germany through the Hartz reforms, argue that while the direct consequences of the reforms on social democratic voters were more limited than is often assumed by the popular press, indirectly, they were highly consequential. Schwander and Mannow argue that the reforms played a crucial role in expanding the popularity and stability of left-wing competitors to the SPD, namely the Linke party, by mobilising voters that lost out from change. At the same time, those that benefitted from the changes in terms of job creation, often continued to face income insecurity, and offered less clear allegiance to the social democrats.

Again, we see the challenge of combining a more technocratic set of policies aimed at accomplishing a goal – here job creation – with electoral imperatives.

The Scandinavian Path – a Model for Social Democracy?

Throughout the post-war era, left parties in the Nordic countries were famously electorally successfully, and today, social democratic parties across the Nordic countries continue to command sizeable vote shares. These parties have also changed, however, in the face of changing industrial and electoral conditions.

While the small, open Nordic economies had long had high levels of trade and exposure to global economic currents, as elsewhere, the combination of increased financial globalization and technological shifts put pressure on domestic manufacturing industries, and spurred a growth of services. As Iversen and Wren (1998) argue, the Scandinavian countries responded to early pressures of de-industrialization by both expanding the public sector and largely maintaining the institutions of wage compression through extensive union bargaining. Structural shifts, combined with an early push to expand female labour force participation, created both a supply and demand for public sector jobs.

The basic contours of this early strategy are in place today. Close to a third of employees in Sweden, Denmark and Norway work in the public sector (compared to an OECD average 21.3 per cent) (OECD 2015). Equally, while unionization rates have fallen in the Nordic countries, a half to two thirds of workers in these countries are still union members, membership levels that dwarf all other European countries, with the exception of Belgium.

This combination of high levels of unionization and the development of high quality service sector work in the public sector, has led political scientist Kathleen Thelen to influentially characterize the Nordic path as one of ‘embedded flexibilization’. Thelen argues that the long-standing investment in skills, combined with explicit bargains between service and manufacturing unions, meant that the Nordic countries were able to transition to more flexible labour market structures without the surge in inequality experienced in the Anglo-world.

Social democrats in the Nordic countries maintain a strong base, and while inequality has substantially increased, these countries continue to have a more egalitarian labour market and electoral success. But differently, this combination appears to square the circle for social democrats, providing them with an economically viable and equitable strategy for growth, which continues to maintain strong links to traditional mobilising agents in unions.

This path, while a long-run model in many ways for social democrats elsewhere, has also faced some challenges. As elsewhere, the combination of traditional working-class voters and newer middle classes within the social democratic base has caused some tensions – notably over migration – but also over the management of public services and greater competition and choice within the public sector (Gingrich 2011). However, in contrast to elsewhere, the ongoing structure of unionization, and in particular the growth of unionized public-sector jobs, has given social democratic parties a continuing base for mobilising around equity issues.

The Post-Industrial Responses: Effective, Visible and Cross-Class?

The above analysis is meant to show that social democratic parties have faced significant challenges, and there is no one-size fits all, off the shelf, approach to economic, social and political success. However, these structural challenges equally do not mean that the mainstream left is doomed. There is appetite for left policies, and in post-industrial economies where skills matter greatly and private employers alone are often not investing sufficiently in skills and infrastructure, there are many areas in which left policies offer both the possibility to expand growth and to improve social equity. Even where spending is less pro-growth, the public often supports spending to help those facing challenges.

The task then for the left is to build and mobilize stable networks around these policies. General investment in skills and more technocratic redistribution alone may not build allegiances to the mainstream left that are as stable as more traditional policies and links to organized labour previously provided. Supporting traditional policies and organized labour, however, has often led to a shrinking base and long-term concerns about growth and employment. The Scandinavian approach of maintaining unionization and expanding the public sector offers some lessons for elsewhere, but may not be fully replicable.

A few potential lessons however, come out of the above experience. First, policies alone may not be enough to build support bases, policies need to be visible to voters and their intermediaries. While third way left parties emphasized efficient solutions, and through the 2000s, often defined the best policy as the one that was least noticeable policy – tax credits, behavioural incentives, ‘nudges’, and so on – efficiency is only one desideratum of good policy. As argued through this paper, efficiency and equity can be highly compatible in the post-industrial economy, but micro-policy efficiency does not guarantee long-run allegiance by voters. Policy-makers on the left may need to consider policies that allow voters to understand the role of the state, by making clear and visible appeals.

Second, in the long-run, skills are absolutely crucial to any successful left strategy. Raising the skills and capacities of citizens is both normatively and economically desirable. But, in the short-run, skills alone are not enough, and mainstream left parties need to support individuals and communities affected by structural economic change. While most left parties clearly recognize this, and electoral support for redistribution and labour market regulation varies, these policies and skill-based investments should not be substitutes. Education can only be one tranche of left policy towards labour markets.

Finally, mobilising public sector workers is likely to be a vital part of any economic and political strategy for social democratic parties, but it alone is not enough. While expanding the public sector workforce has been an important part of the long-run Nordic strategy both economically and politically, elsewhere, conservative parties have often mobilized against public sector workers. This mobilization is particularly virulent in the United States, with a number of states taking more restrictive positions towards public sector workers.

Mobilization of the young, private sector workers, and other groups outside the labour force will be important to the long-run success of social democratic parties. In an era of declining unionization, other forms of mobilization have emerged, such as Organizing for America around the Obama campaign. These organizational strategies have often successfully brought voters to the polls, but struggled to create networks outside of electoral cycles (something that contrasts to quite successful grassroots mobilization through the Tea Party and churches for the Republican party). Investing in greater mobilization is crucial to the long-run success of social democrats.

The above paragraphs are not meant to advocate a return to inefficient policies or machine politics, but rather, to suggest that connecting the efficient and popular policies to durable electoral support requires some attention to the way policies are perceived by voters and the organizational structures on the ground that sustains them.

Notes

1. These data are compiled from the European Regional database (Cambridge Econometrics 2014) and exclude one Scottish region (UKM6) for presentational ease.

2. The average unemployment rate between 1991 and 2014 in French regions with greater than 20 per cent industrial employment in 1991 was 9.5 per cent, whereas in similar British regions it was 6.3 per cent over this period (author’s calculation, from European regional yearbooks and Eurostat).

3. In addition, in some context, growing income inequality has led to concerns of disproportionate policy influence by higher income voters or interest groups (Gilens 2012).

4. The rate of increase in higher education has been slower in some Continental countries. The Nordic countries, see below, have similar levels of education, but began expansion somewhat earlier. The Southern European countries also dramatically expanded higher education during this time, but from a lower baseline.

5. The data on pension and unemployment replacement rates come from the CWED-2 dataset (Scruggs 2014). The data on child benefits are from the Child Benefit Dataset (SOFI 2015).

References

Ansell, Ben W. ‘University challenges: Explaining institutional change in higher education’, World Politics 60(02) (2008) pp. 189–230.

Autor, David H., Levy, Frank and Murnane, Richard J. ‘The skill content of recent technological change: An empirical exploration’, The Quarterly Journal of Economics (2003) pp. 1279–333.

Beramendi, Pablo, Häusermann, Silja, Kitschelt, Herbert and Kriesi, Hanspeter. The Politics of Advanced Capitalism (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press 2015).

Berman, Eli and Machin, Stephen. ‘Skill-biased technology transfer around the world’, Oxford Review of Economic Policy 16(3) (2000) pp. 12–22.

Boix, Carles. Political Parties, Growth and Equality: Conservative and Social Democratic Economic Strategies in the World Economy (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press 1998).

Chote, Robert, Crawford, Rowena, Emmerson, Carl and Tetlow, Gemma. ‘Public spending under Labour’, Institute for Fiscal Studies (2010).

Cingano, Federico. Trends in Income Inequality and its Impact on Economic Growth (OECD, Paris 2014).

Cambridge Econometrics. European Regional Database (Cambridge, Cambridge Econometrics 2014).

European Commission. European Regional Yearbook (multiple years).

European Social Survey Cumulative File, ESS 1–7 (2016). Data file edition 1.0. NSD – Norwegian Centre for Research Data, Norway – Data Archive and distributor of ESS data for ESS ERIC.

Gilens, Martin. Affluence and Influence: Economic inequality and political power in America (Princeton, Princeton University Press 2012).

Gingrich, Jane. ‘A new progressive coalition? The European left in a time of change’, The Political Quarterly 88(1) (2017) pp. 39–51.

Gingrich, Jane and Häusermann, Silja. ‘The decline of the working-class vote, the reconfiguration of the welfare support coalition and consequences for the welfare state’, Journal of European Social Policy 25(1) (2015) pp. 50–75.

Goldin, Claudia and Katz, Lawrence F. The Race between Education and Technology (Cambridge MA, Harvard University Press 2009).

Heckman, James J. ‘The economics of inequality: The value of early childhood education’, American Educator 35(1) (2011) p. 31.

Iversen, Torben and Wren, Anne. ‘Equality, employment, and budgetary restraint: the trilemma of the service economy’, World Politics 50(04) (1998) pp. 507–46.

Kitschelt, Herbert. The Transformation of European Social Democracy (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press 1994).

Moretti, Enrico. The New Geography of Jobs (New York, Houghton Miin Harcourt 2012).

OECD. Government at a Glance (Paris, OECD 2015).

OECD. Education at a Glance (Paris, OECD 2016).

Oesch, Daniel. Redrawing the Class Map: Stratification and Institutions in Britain, Germany, Sweden and Switzerland (New York, Springer 2016).

Ostry, Jonathan David, Berg, Andrew and Tsangarides, Charalambos G. Redistribution, Inequality, and Growth (International Monetary Fund 2014).

Rueda, David. ‘Insider–outsider politics in industrialized democracies: the challenge to social democratic parties’, American Political Science Review 99(01) (2005) pp. 61–74.

Schwander, Hanna and Philip Manow. ‘ “Modernize and Die”? German social democracy and the electoral consequences of the Agenda 2010’, Socio-Economic Review 15(1) (2017) pp. 117–34.

Scruggs, Lyle, Jahn, Detlef and Kuitto, Kati. ‘Comparative Welfare Entitlements Dataset 2. Version 2014–03’, University of Connecticut and University of Greifswald (8 July 2014). Available at http://cwed2.org (Accessed 16 July 2017).

SOFI, Social Policy Indicators SPIN, The Child Benefit Database. Technical report, Stockholm University (2015).

Thelen, Kathleen. Varieties of Liberalization and the New Politics of Social Solidarity (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press 2015).

Valero, Anna, Van Reenen, John et al. ‘How universities boost economic growth’, Technical report, Centre for Economic Performance, LSE (2016).

Visser, Jelle and Hemerijck, Anton. A Dutch Miracle: Job growth, welfare reform and corporatism in the Netherlands (Amsterdam, Amsterdam University Press 1997).