11

The Experience of Slavery

Harriet Beecher Stowe studied slavery in Kentucky for her novel Uncle Tom's Cabin, and one reason the book was a best seller and the drama based on it played to overflow crowds in the North was that she brought to life in fiction the most heartbreaking aspect of Kentucky slavery—the breakup of families when slaves were sold and taken away to the Lower South, many of them chained in coffles. The story begins on the Kentucky farm of Mr. Shelby, a kind master who loves his slaves and treats each one with respect. But the fictional Mr. Haley, a slave trader, comes to purchase slaves—many slave traders came to Kentucky from 1830 to 1860 to purchase slaves and take them South—and Shelby owes Haley money and is forced to sell Uncle Tom, a Christian family man with a wife and children and the leader of the slaves on the plantation. Haley takes Tom away, and, eventually, he is beaten to death by Simon Legree, an evil slave owner, in Texas. Stephen Collins Foster recognized the pathos in the story, and, from the point of view of Uncle Tom longing to return to his home in Kentucky, he wrote the song Poor Uncle Tom, Good Night, with the chorus:

Oh good night, good night, good night

Poor Uncle Tom

Grieve not for your old Kentucky home

You'r bound for a better land

Old Uncle Tom.

Foster later changed the lyrics and renamed the song “My Old Kentucky Home, Good-Night!” In 1928, Kentucky adopted it as the state song.1

Slavery was part of Kentucky society from the earliest beginnings. When

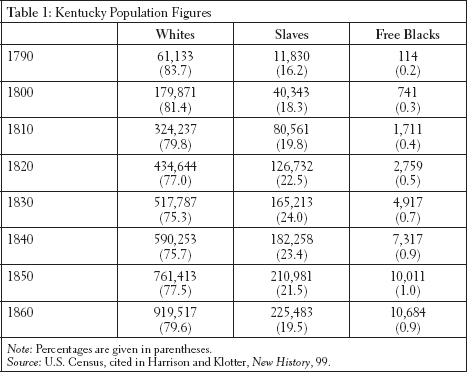

the first white settlers entered the area, they brought slaves with them. In 1773, when Daniel and Squire Boone attempted to settle several families in the Bluegrass region, they brought an unknown number of slaves. By the turn of the nineteenth century, there were 40,343 slaves, or 18.3 percent of a total Kentucky population of 220,955, and there was a steady increase in the number of slaves to 225,483 in 1860. However, the percentage of slaves in the total population reached a high in 1830 at 24 percent. A decline in slaves as a percentage of the population began at that point and continued until the end of slavery in 1865.2

With regard to slavery, Kentucky adopted Virginia law and practice, which viewed slaves as chattel property. A slave code was adopted in 1798 to regulate the activities of slaves with their masters and the wider community. However, these codes were not always enforced. Laws concerning slavery were added throughout the first half of the nineteenth century to include the right of owners to emancipate slaves in a will, the provision that owners were to be compensated for slaves executed for capital crimes, and the prohibition of sales of alcohol to slaves and free blacks. Slaves were prohibited from owning property, moving throughout the community without a pass, owning a firearm, and congregating. Kentucky law did not recognize slave marriages, and the children of a female slave were the property of her owner. Unlike many other southern states, Kentucky did not pass a law prohibiting the teaching of slaves to read and write, but few slaveholders actually educated their bondsmen. State laws were supplemented by codes passed in various communities to confront the issues and fears of a white population as time passed.3

Many white Kentuckians owned slaves, but the average number owned was relatively small, and Kentucky masters had the reputation of being more humane than overseers and masters in states with larger plantations. The 1850 census listed 139,920 white families in the state, and 28 percent, or 38,385, owned slaves. Relative to the other slave states, this was a high percentage; only Virginia with 55,063 and Georgia with 38,456 had more families who owned slaves. However, among the 38,385 people who owned slaves in Kentucky in 1850, only five held more than one hundred, while 88 percent held fewer than twenty, and 24 percent owned only one. In 1850, the average holding in Kentucky was 5.4 slaves, and in this regard the state ranked thirteenth among the fifteen slave states. South Carolina had an average of 15 slaves per family of white slave owners, and Mississippi had 13.4. Only Missouri with 4.6 and Delaware with 2.8 averaged fewer than Kentucky.4

Another distinctive feature of Kentucky as a slave state was the relatively lower percentage of slaves in the population. In 1860, when the population of Kentucky was 19.5 percent slave, that of Virginia was 30.7 percent, that of Mississippi 55 percent, and that of South Carolina 57 percent. The distribution of slaves was most concentrated in the Bluegrass region, with large numbers in the south-central region and in Henderson and Oldham counties on the Ohio River. In 1860, 21 of Kentucky's 109 counties had a slave population over 30 percent, but 23 of the 109 had under 5 percent. The lowest percentages of slaves were in the eastern mountains and the northern and west-central portions of the state.5

Because cotton, rice, and sugar were not profitable crops in the region and so many slaves lived on small farms, slavery did not come to dominate the Kentucky labor force as it had in other southern states. On small farms, slaves lived and worked alongside their white masters. They performed the everyday duties that helped make a farm profitable, such as animal husbandry, crop planting and production, transportation of goods to market, home manufacture of cloth and soap, and clearing and maintaining land. Hemp proved a valuable commodity for Kentucky farmers, and its cultivation encouraged the growth of slavery. Most of the crop was sent south in the form of rope, raw bagging used to wrap cotton bales, and rough cloth for slave clothing. Kentucky dominated the supply of hemp to the Lower South prior to the War of 1812.6 Slaves did most of the work on hemp farms and in the factories where hemp was processed. For a successful hemp crop, the soil needed to be “deep, loamy, and warm and should contain an appreciable amount of humus…. The Bluegrass region of Kentucky, owing to its deep, calcareous and highly fertile soil, was well adapted to the production of this staple.”7 Although cultivating a hemp crop was not as labor intensive as cotton or tobacco, it required year-round attention. Hemp farmers said that they believed that African Americans best understood how to grow, harvest, break, and hackle the wood stalks to extract a high-quality fiber.8 One white slave owner remembered that cutting and breaking hemp “was the hardest work done on a Kentucky farm.”9 Male slaves dominated the cultivation of hemp, and their use in breaking the hemp stalks continued as long as the crop was grown in the state.

The use of slaves in hemp production went beyond the field to manufacturing. As early as 1809, Thomas Bodley and Company in Lexington advertised for ten “Negro” boys and five men to work in the factory spinning and weaving hemp cloth. John Wesley Hunt employed between forty and fifty slaves in his hemp factory in 1806—he rented at least ten and owned the others. When he decided to leave manufacturing in 1813, he auctioned off his sixty skilled slaves, and they included African American men, boys, and women. By the middle of the nineteenth century, there were 159 hemp factories in Kentucky, one-third of the national total, that employed close to three thousand African Americans. In 1860, the number of those employed in Kentucky hemp factories had increased to five thousand, with most found in Lexington and Louisville.10

The task system was used in hemp production both in the field and in the factory. Field workers on one Jefferson County farm were required to cut a “land,” about a twelve-foot-wide span, and most could finish by early afternoon. When it was time to break the stalks, each man was to break 100 pounds of hemp each day. For each pound over 100, a slave would be paid one cent. Thomas Bullitt, who lived at Oxmoor Plantation in Jefferson County, remembered that most men could break 125-160 pounds in a day. The fibers would be weighed carefully by the white master at the end of each day, and overage pay was handed out at the end of the week. In the factory, slaves were also given tasks to perform and were paid two to three dollars for any overwork.11

Slaves worked in most aspects of the Kentucky economy. They were employed in the Bath County ironworks, the Clay County saltworks, and the iron and lead mines of Caldwell and Crittenden counties.12 The most common jobs for slaves were as field hands, carriage drivers, house servants, seamstresses, stable boys, and dairymaids. Field hands were the most isolated from the outside world as their world revolved around the field and slave quarters. They rose before sunrise and worked until sunset.13 On some farms, women were excluded from fieldwork and were supervised by the mistress of the property. The women “were required to take care of their families; to keep their houses clean; to spin; to sew, and to do housework.”14 House servants cooked, cleaned, did laundry, and cared for the sick. Their position tended to isolate them from the larger slave community, but many preferred the station because they considered the work easier. Henry Bibb, born in Shelby County in 1815, worked at washing, furniture polishing, and scrubbing floors. One slave had the duty to keep flies off the dinner table, and another, a blind boy, carried water in a bucket on his head from the spring to the house each day.15 House servants had better clothes and were trained to have better manners; they would eat the same food as the white family. Some of these slaves also learned to read and write, which led many to adopt “an air of superiority over the field hands.”16 The opportunity to work as a domestic could benefit a slave in the development of a close relationship with the master, and this could mean a better chance at emancipation. Robert Wickliffe, the largest slaveholder in Kentucky, manumitted only one slave at his death—his personal manservant, William Box.17 However, the close proximity to the master might also lead to abuse. While Henry Bibb worked as a house servant, he recalled that his mistress had him “rock her and keep off the flies. She was too lazy to scratch her own head, and would often make me scratch and comb it for her…make me fan her while she slept, scratch and rub her feet; but after awhile she got sick of me, and preferred a maiden servant to do such business.”18 The mistress of Annie B. Boyd would stick her with a pin each night if she fell asleep before completing her chores for the day. Boyd reported that she was “a mean woman.”19

Many slaves had special skills used on farms and in towns; these slaves were blacksmiths, weavers, spinners, carpenters, and horsemen. In 1849, the advertisement “Negro Lawyer at Auction!” appeared in the Louisville Courier, offering for sale a “yellow man” who was “a very good rough lawyer.” While the seller could not recommend the slave for representation in the Court of Appeals, he could “make out legal writings, and is thoroughly adept at brow-beating witnesses and other tricks of the trade.”20 In 1838, Stephen Bishop, a slave, began giving guided tours of Mammoth Cave and discovered many of the cave's most famous attractions through his own explorations. Slaves delivered mail, they built roads, fences, and bridges, and they worked in hotels and restaurants as cooks, waiters, and maids. Others worked at the docks or on riverboats that traveled the Ohio, Kentucky, Green, Cumberland, Barren, and Tennessee rivers. Lexington merchants and brothers John Hunt Morgan and Calvin Morgan rented out two slave crews on boats on the Ohio and Mississippi rivers in the late 1850s. Steamboat accidents made it a dangerous life; living conditions were damp and unhealthy, and between voyages overseers put the crews to work scouring decks and rolling barrels and cotton bales on the levee.21

Some slaves did not work directly for their masters but were hired out. The process of hiring out allowed manufacturers some flexibility in that they could vary the size of their labor force on the basis of current market trends and gave small farmers the benefit of slave labor if they did not have the capital to purchase a slave. In urban areas, slaves would be hired out as hemp workers, cooks, washerwomen, housemaids, hotel waiters, porters, draymen, mechanics, and deckhands and cabin servants on steamboats. Rates ranged widely on the basis of skills and the needs of the market, but a one-year contract ranged from $75.00 to $150.00 a year plus the cost of boarding. The week between Christmas and New Year's Day was a period of intense negotiation, and numerous newspaper ads described the bondsmen and-women for hire; most contracts ran from January 1 to Christmas Day.22 While owners were responsible for property taxes due on the slave, contracts stipulated that employers had to provide boarding, clothing, and proper treatment for the hiring term. When a slave hired out by Robert Wickliffe's daughter Mary fell ill and did not receive adequate care, Wickliffe reprimanded the hotel proprietor, J. H. Shopshire, for neglect. Shopshire acquiesced to the chastisement and responded: “I know it is our duty to keep the negro during his sickness and have him properly attended…. [He] is in very comfortable quarters and will receive all the attention or probably more than the law would require of us.”23

Hiring out also held advantages for the slave. Many of those contracted to work in urban areas found themselves with unsupervised time after their daily work was over. In the factory, many supervisors used the task system with quotas of work to encourage production. After finishing a task, a slave might be paid a bonus for any additional work performed. In the 1850s, a slave might earn two to three dollars a week. These bonuses, saved over the course of several years, could provide the slave the opportunity to purchase his and his family's freedom. Some slave owners wrote into hiring contracts that a portion of the payments for additional work would go to the owner, but a slave could save the remainder of his bonuses for personal use. The same payments also occurred on the hemp farm, and slaves on farms could make extra money with small gardens they were permitted to cultivate. The more industrious slaves also made mats, shoes, and chairs in their spare time to sell.24

Slave owners in Kentucky often viewed themselves as benevolent masters who provided for their slaves from birth to death. One Kentucky master confided to his diary that he had not made any money from his slaves but that all proceeds had been used to care for the old and the young in his possession. He wrote: “I have supported my negroes and not they me.”25 Robert Wickliffe, who owned close to two hundred slaves and was, therefore, the largest slaveholder in Kentucky, often referred to his slaves as “family” in letters to his own children.26 Historian Eugene Genovese described slavery as a paternal system under which masters viewed themselves as caring fathers of their slave children. This mind-set allowed whites to view the labor of their slaves as a willing exchange for provision and protection.27 This is illustrated in the comments made by Thomas Bullitt when he reflected on the slaves his family owned in Jefferson County: “According to my best impression the negro in Kentucky—at least on my father's place—having been born in slavery, knowing for himself or his race no other condition, did not repine; did not aspire to anything beyond it. If not happy, they were contented, and were certainly capable at times of great fun and pleasure.”28

Slaves were provided with many of their basic needs. It was never in the best interest of the slave owner to mistreat those in his possession. The value of a slave's labor was his best protection from harm and the best motivation for masters to provide the necessities of life. Slave clothing was most often made of homespun and would be dyed with sassafras, berries, or indigo. Women slaves might wear the castoffs of the mistress, and small children would run naked or in shirts that reached to their knees. On small farms, slaves would be given clothing according to need, but, on large farms, allotments would be made in the spring and fall. By studying the newspaper ads for Kentucky runaways, it is apparent that their clothing was quite varied. Pants ranged from stripes to plaids and from twills to Kentucky jeans. Shirts were of blue linen, checked linen, cotton, plain linsey, calicos, kerseys, and more. Descriptions also mentioned waistcoats, overcoats, fur hats, and woolen caps. The amount of clothing slaves possessed was never great, and it is estimated that they were able to change clothes about once a week.29

Some masters purchased ready-made clothing for slaves, and merchants made a clear distinction between clothes made for whites and those made for African Americans. Those stocking items for slave use advertised “negro goods,” and clothing for white people was labeled “fashionable…for ladies and gentlemen.”30 On larger farms, clothing was made on-site for the slaves. Will Oats, a former slave, remembered that his family “all wore home made clothing, cotton shirts, heavy shoes, very heavy underwear; and if they wore out their winter shoes before the spring weather they had to do without until the fall.” Bert Mayfield described the scene each year when the slaves received their new clothing: “On Christmas each of us stood in line to get our clothes; we were measured with a string which was made by a cobbler. The material had been woben [sic] by the slaves in a plantation shop. The flax and hemp were raised on the plantation.”31 At Robert Wickliffe's Piedmont Farm in Bath County, two slave women rejected the clothing being made by the overseer's wife. They spoke impudently to the white woman and pronounced that the clothing rations at a neighboring farm were much better.32

Slave quarters also varied. On farms with only one or two slaves, the slaves would live in the same house as the family and sleep on the floor in a loft area. On larger farms, separate quarters were provided, and conditions depended on the means of the master. Some were brick cabins, but most were log with a stone or brick fireplace and a dirt floor. The cabins were usually one room with a loft and totaled about one to two hundred square feet. Wes Woods, another former slave, described the living situation on the farm where he grew up:

There were three or four cabins for the slaves to live in, not so very far from the house…. Our cabin was one long room, with a loft above, which we reached with a ladder. There was one big bed, with a trundle bed, which was on wooden rollers and was shoved under the big bed in the daytime…. The cabins were built of logs and chinked with rock and mud. The ceiling was of joists, and my mother used to hang the seed that we gathered in the fall to dry from these joists. Some of the chimneys were made with sticks and chinked with mud, and would sometimes catch on fire. Later people learned to build chimneys of rock with big wide fire places, and a hearth of stone, which made them safer from fire.33

The slave diet consisted of the basics of any lower-class southern diet: meat, meal, and molasses. One master told a northern visitor that the slaves met on Sunday mornings to receive “four pounds of pork…a peck of meal, and a half gallon of molasses.” On special occasions, the master might give out a ration of coffee, sugar, candy, and fresh meat. The amount of food was usually adequate, especially those crops in season and during good production years. Even if rations were small, slaves were permitted to tend small gardens from which they could supplement their diet with fresh vegetables and herbs. These gardens produced sweet potatoes, Irish potatoes, watermelons, cantaloupes, strawberries, corn, and squash. Some farms had orchards where the slaves found peaches, apples, and pears. Chickens added eggs and the occasional fryer for meal variety, and masters encouraged slaves to hunt raccoon, rabbit, squirrel, and other animals with firearms regardless of the slave code. Slaves baked small game in ovens, and small fish were “rolled in meal and cooked in a big skillet” to be eaten with corn pone. By present nutritional standards, the slave diet was high in fat and lacking in calories and nutrients because of the cooking processes used.34

Masters also cared for their slaves' medical needs. The billing records of doctors indicate that slaves were treated along with white families for illnesses and injuries. The health of a slave was important to masters, for a slave who could not work was not worth the cost to maintain. Robert Wickliffe paid bills for the bleeding of slaves, doctor's attendance at births, and the setting of broken bones. In 1854, Wickliffe fired the overseer of his Owingsville farm for shooting a recalcitrant slave, yet he simply reprimanded another overseer for whipping another slave. The value that Wick-liffe placed on the health and well-being of his slaves is apparent. While a whipping might rob the farm of a slave's labor for a day or two, a gunshot wound was potentially fatal and could lead to a significant loss of property. On many farms, the white mistress looked after sick slaves. Thomas Bullitt recalled his mother's actions when several slaves came down with typhoid fever. She placed a slave nurse in charge of each patient and then each night before bed and again around one o'clock in the morning “went the rounds of the cabins to see their condition and to give directions.” Another former slave remembered: “The white folks looked after us when we were sick. used dock leaves, slippery elm for poultices. They put polk root in whiskey and gave it to us.”35

Diligent care, however, was not extended to those slaves who misbehaved and failed to do their duty. Slave codes, established in Kentucky in 1798 and throughout later years in various communities, restricted the movement of slaves and regulated their relations with whites. The willingness of Southerners to prosecute slaves charged with crimes proved that their “property” was, in fact, something more. Slaves who normally lived outside the boundaries of legal rights were brought into the legal system for punishment. Slaves charged with misdemeanors did not receive jury trials, but felony charges required a trial by jury and a defense counsel. Convictions presented communities with the problem of how to punish a slave. Because they owned no property, levying fines was useless; jail sentences robbed the owner of his slave's work during the period of incarceration; and death sentences terminated the owner's right to property. Misdemeanor convictions usually resulted in a severe whipping, and a felony conviction in cases of rape, arson, murder, or burglary was punishable by death. If a death sentence was passed, the state would assess the value of the slave and pay the owner for his loss from public funds. Until 1847, Kentucky law allowed slaves convicted of capital crimes and sentenced to death to plead “benefit of clergy.” A judge would sometimes grant the benefit when the conviction was based on little or no evidence, as with arson, which was very difficult to prove. The judge would sentence the convicted slave to an alternate punishment of flogging or branding in the palm of the hand.36

On the farm, whipping was the most common form of punishment. Henry Bibb, who escaped slavery in the 1830s and wrote a narrative of his experiences, referred to his childhood in Kentucky as being “flogged up; for where I should have received moral, mental, and religious instruction, I received stripes without number.”37 A former slave remembered seeing “a light colored gal tied to the rafters of a barn, and her master whipped her until blood ran down her back and made a large pool on the ground.” Another stated that, when the master thought his slaves were not working hard enough, “he would tie them up by their thumbs and whip the male slaves till they begged for mercy.” Persistent runaway slaves were branded on the chest or body, cropped on the ear, or had an iron band attached to their ankle. In some cases, iron collars with bells would be attached to the neck to prevent a slave from successfully hiding from the master. The ultimate punishment for a slave was to be sold “down the river.” For the slave, this “was a genuine terror” because it was “a permanent separation from his family and friends” and “an introduction into new and untried conditions, which to his mind were terrible.” Thomas Bullitt remembered his father selling only one slave, a woman named Caroline, who was “defiant and uncontrollable.”38

Kentucky law prohibited masters from abusing their slaves and provided that they must take care of them when they were old and infirm. Public opinion usually kept most masters' behavior in check, and prosecutions of whites for slave mistreatment were rare.39 However, some cases were so severe that local authorities had to take action. Such is the case of Lilburne and Isham Lewis. The Lewis brothers, nephews of President Thomas Jefferson, lived on a plantation in Livingston County. They were known for their cruel treatment of the numerous slaves they owned, and many of their slaves ran away. The night of December 15, 1811, Lilburne and Isham were drunk, and they decided to make an example of George, one of the recent runaways who had returned after a brief stint in the nearby woods. They ordered George to get water from the spring using a glass pitcher that the brothers claimed was one of their late mother's heirlooms. While the slave left on his errand, the other slaves were gathered at gunpoint in the largest slave cabin as witnesses of the lesson. George returned to the cabin begging for mercy because he had broken the pitcher. Isham ordered George tied up, and Lilburne brought in a meat block and large ax. In front of a horrified group of slaves, Lilburne proceeded to strike George in the neck with the ax, killing him as he drunkenly lectured them about obedience. He continued to chop George into pieces, and, to cover their actions, the brothers burned his body in the fire until late into the night. After warning their slaves not to tell, the two were convinced that their secret was safe.

However, that night the New Madrid earthquake struck, and the chimney in which George's body had been burned collapsed. The slaves were ordered to hide the bones within the rebuilt chimney, but another wave of earthquakes caused another collapse, and a dog came by and carried off a jawbone. A neighbor noticed the dog chewing on the bone and notified authorities. They searched the Lewis farm, found the remains of George, and arrested Lilburne and Isham. While out on bond, they were indicted for murder, and the sheriff returned to their farm on April 10, 1812, to bring them to jail for trial. Well aware of community sentiment and their arrest, the two decided to take their rifles and kill each other. Lilburne accidentally shot and killed himself, and Isham, in shock, ran away to hide in the woods. He was captured and put in the county jail, where he was charged as an accessory to his brother's murder. He was sentenced to be hanged but escaped from the jail never to be seen again. Rumors circulated that he traveled south to Natchez and was later killed at the Battle of New Orleans.40

Even in the face of cruelty, slaves had little recourse against their masters, as seen in the case of Caroline Turner. The wife of retired judge Fielding L. Turner, Caroline was a cruel mistress with a temper. Her husband admitted that she had caused the death of six servants by severely beating them. In the spring of 1837 in Lexington, she lost her mind while whipping a slave, grabbed a small slave boy, and threw him out a second-story window to the paved courtyard below. The slave was crippled for life, and Judge Turner had Caroline confined in the lunatic asylum. She protested; the asylum authorities ruled her sane and released her. She was not charged for the assault. Her husband attempted to protect his slaves from her cruelty by stipulating in his will that his slaves were to go to his children and not his wife. However, Caroline had portions of the will overturned and received a few slaves. On August 22, 1844, she was beating a young slave named Richard when he struck back at her and strangled her to death. He was apprehended in Scott County and tried for murder. Although Caroline Turner's history of cruelty was well-known, Richard's act of self-defense was too much for Kentucky society to handle. He was convicted and hanged in the Fayette County jail yard on November 19, 1844.41

Despite cases of cruelty and the lack of help from white authorities, bondsmen and-women did resist their enslavement in numerous ways. The most common form of resistance was the slowdown of work. But slaves also feigned illness and destroyed property, such as tools and crops. Arson was commonly used to destroy outbuildings or manufacturing operations in urban areas. There were nine suspicious manufacturing fires in Lexington during the six years before the War of 1812. John Wesley Hunt had his hemp buildings set afire twice. The first time in 1807, a slave boy was convicted of arson and sentenced to be hanged. After rebuilding, the establishment was again set ablaze in 1812, this time by two slave boys under the age of fifteen. The two were sentenced to death, but in a controversial decision Governor Charles Scott pardoned the pair because of their age.42

Stealing food items was commonly recognized by masters as a subtle form of resistance. This was almost expected among many white slave owners and tolerated as long as items taken were not sold for money. One slave woman decided to take some of the cookies she was making for the white family. She placed them under a cushion on a chair to avoid detection, but the mistress's pet parrot cried, “Mistress burn, Mistress burn,” when she entered the room. The cookies were discovered and the slave whipped. However, the bondswoman exacted her revenge the next day by killing the pet parrot. More severe forms of resistance involved slaves mutilating themselves to avoid work or even in some cases committing suicide. There were also a few instances when slaves attacked or killed an overseer or master. Jim Kizzie, an overseer in Henderson County known for the free use of his whip, was seized by several slaves in a tobacco field August 4, 1862. Using their suspenders, the slaves formed a noose and strangled him. Five slaves were arrested and charged with murder. Four of the five were acquitted, but the leader, named Daniel, was executed on February 6, 1863, in front of a crowd of local slaves brought in by their masters to witness what happens to a rebellious slave.43

White society most feared a general slave insurrection or uprising. In 1811, a year following the uncovering of an insurrection plot in Lexington, the state legislature made any involvement in a rebellion punishable by death. Another plot was stopped in Boone County in November 1838, and six of the slaves involved escaped across the Ohio River and found their way to Canada. Widespread rumors of a Christmas Day insurrection circulated throughout the state in 1856, and in most cases the slaves had more to fear for their safety than did the whites because in times of panic white authorities would accuse innocent blacks of violent revolt. There were some disturbances in Clarksville, Tennessee, that turned into a report that six hundred slaves were headed north to Hopkinsville on their way to freedom. Various lynchings and slave roundups occurred across the state as rumors of slaves destroying telegraph lines, killing whites, and participating in other vicious plots circulated.44

One slave insurrection struck fear in the hearts of whites in central Kentucky. Citizens of Fayette County awoke on the morning of August 5, 1848, to discover that, overnight, approximately seventy-five slaves had armed themselves and escaped. There were reports that the group was headed to the Ohio River. Many in the community were shocked to learn that a Centre College student, Patrick Doyle, had aided the group. Doyle sought personal fame through his actions and had only a week earlier escaped a Louisville jail cell for trying to sell several free blacks he lured from Cincinnati. An immediate search party was formed and a five-thousand-dollar reward offered. Three days later, the slaves were surrounded in a hemp field on the border of Harrison and Bracken counties; some shots were fired, but the group surrendered. Forty-seven African Americans went through a three-day trial in the Bracken County Circuit Court, where they were found guilty. Three of the forty-seven were hanged on October 28, 1848. Patrick Doyle, whose real name was Edward J. Doyle, was apprehended and taken to Lexington, where he pled guilty to the charge of insurrection in the Fayette County Circuit Court. He was sentenced to the state penitentiary for twenty years on October 9, 1848.45

While most slaves did not resort to arming themselves against their masters, running away was a method of resistance that they did use. Some runaways left their masters for short periods of time in order to avoid an upcoming punishment or work schedule. In this case, the slaves generally stayed in the area close to their home and returned to some form of punishment from the master. Henry Bibb commented: “I learned the art of running away to perfection. I made a regular business of it.” Another former slave remembered that, once, when a runaway returned to the farm, “my old master picked up a log from the fire and hit him over the head.”46

Other runaways left their homes for freedom in the North. This scenario was a greater possibility for slaves in Kentucky than for those in the Deep South because of the long border with free states. State law made it illegal to help slaves escape, and many residents, even those who opposed slavery as an institution, would turn in escaped slaves. A careful study of fugitive-slave narratives revealed that the majority of slaves who escaped to the North found very little help while in a slave state. The underground Railroad, which was very active across the Ohio River from Ripley to Cincinnati, was unknown by many Kentucky slaves, who did not find help from abolitionists until after crossing the river on their own.47 Newspapers would carry ads run by masters looking for runaways in rivertowns. The Licking Valley Register carried the following ad on August 10, 1844: “$20 Reward. Ranaway [sic] from the subscriber, living 6 miles southwest of Danville, in Boyle county, on the morning of the 24th inst. a NEGRO MAN, named FENORITY, Though commonly called and answering to the name of ‘NOTT.’ Nott is about 20 years of age, 5 feet 8 or 9 inches high, spare made, shows his teeth in speaking, and has the two upper front teeth broken off. He can read and write and he may have forged free papers or a pass.”48 A. Irvine offered fifty dollars if Nott was captured in “a more remote part of the State.”49

Not all slaves who attempted a border crossing were successful. Many fugitive slaves were captured as they crossed or once they reached the other side. The Covington Journal reported an escape attempt by seven slaves from Washington, Kentucky, on September 9, 1849. While trying to cross the Ohio River, their small boat capsized, four of the group drowned, and the remaining three were captured and put in jail to await return to their masters. One of the most famous escape attempts in Kentucky history was that of the Garner family, and it is illustrative of the lengths that some bondsmen and-women went to in order to escape slavery. In late January 1856, the eight members of the Garner family, along with nine other neighboring slaves, left Boone County at night to cross the river to Cincinnati. using a horse and a sled, they quickly proceeded to the river just below West Covington, where they crossed the frozen Ohio on foot. At daybreak, they entered Cincinnati and broke into two groups to avoid suspicion. The Garners made inquiries at several locations for a man named Kite who was a former slave from their neighboring area. Their presence on the streets drew attention and led to their betrayal. Pursuers learned the location of the family and surrounded the house, which had been locked and barred. The family, not wishing to return to slavery, put up a fight. Simon Garner fired several shots as the men entered the room, but he was apprehended and dragged outside. Margaret Garner, realizing that the return to slave life was imminent, grabbed a butcher knife from the table and cut the throat of her three-year-old daughter, not wishing to see the child returned to bondage.

She attempted to kill the other three children and herself but was overpowered and taken to jail. After a two-week trial to determine what should happen, the family was returned to their owner, Archibald K. Gains. A Cincinnati newspaper reported that, as they returned to Boone County, the boat began to sink, and Margaret and her infant were thrown into the river. The infant drowned, but Margaret expressed little remorse for she believed that the child had escaped a worse fate. Eventually, both she and her husband, Simon, were sold downriver in New Orleans, and it was reported that Margaret died in 1858 of typhoid fever.50

Kentucky slaves used the creation and sustaining of family life to help counteract some of the hardships of slavery. Even though Kentucky law did not recognize slave marriages, slave owners generally encouraged their slaves to find mates. The best situation would be for a slave to find a mate on the same farm; however, this was not always possible. If a prospective spouse lived on another farm, permission from both masters had to be obtained. Some owners might reject such an arrangement, but many granted their permission. Some slaves began marriage at once by living together, but others had wedding ceremonies led by the owner or a local black preacher. The most common ritual associated with slave marriages was “jumping over the broomstick,” where the couple acknowledged their married state by stepping over a broomstick on the ground. Slave weddings were joyous occasions and were often followed by a large meal, dancing, and singing. Masters viewed slave marriages as a way to tie individual slaves to their farm or interests. Married slaves, and especially those with children, were less likely to run away. Religious convictions at the time also reinforced the idea of marriage for slaves even though it was an extralegal institution. The fact that many slaves were brought under church discipline for adultery gives evidence that the church gave the black family a legitimacy that did not exist in secular society.51

Although a household might not have both father and mother present, the family was an important institution. Interviews with former slaves indicated that several did not remember fathers or grandfathers but recalled family life with mothers, grandmothers, and siblings. These individuals described their family as having been headed by a woman, and this reflects the nature of slavery in that the father may have been sold or was living elsewhere. On the other hand, many interviewees stated that they remembered two-parent households. Madison Campbell, who grew up in Madison County, remembered both his father, Jackson, and his mother, Lucy, and a maternal grandfather who lived on a neighboring farm until he purchased his own freedom. His maternal grandmother had been sold south from another local farm, and Campbell could not recall her. He experienced little in the way of physical punishment throughout his childhood and carried with him as his greatest fear the threat of separation from family. He married, and his wife and children lived on another local farm. Eventually, the extended family was separated through the death of the master. Campbell's mother, four of his brothers, a sister, and several nieces and nephews were sold. The widowed mistress kept Campbell, his father, and one sister. He convinced the owner of his wife to hire him to keep his own immediate family together. Although husband and wife each would later be sold locally, Campbell purchased his own freedom and remained close enough to his wife and children to reunite with them after the Civil War.52

Many masters honored marriage ties and tried to avoid separating families unless they were in severe economic need. But individual slaves were still pieces of property, and the bonds of marriage and family could prove tenuous. Steve Kyler, a Garrard County slave, had over years of being hired out earned enough money to purchase his freedom. When his wife's owner planned a move, Kyler's former master arranged to purchase Cynthia and gave the bill of sale to Kyler. Years later, Kyler found himself in serious debt, and his creditors sued him for payment in court. Kyler believed that he had nothing to fear because he owned no real property and that the courts would order him to pay as he could. However, in the summer of 1856, law enforcement officials arrived at Kyler's door to take Cynthia for sale and debt repayment. After retaining Allen Burton as his lawyer, Kyler filed a temporary injunction to stop the sale, and his case went to the Garrard County Circuit Court. Allen Burton argued before the court that Kyler's former master understood that Cynthia was a wife only and not a piece of slave property when he handed the bill of sale to Steve. The creditors argued that no provisions had been made in the master's lifetime or in his will for her freedom and that, therefore, she remained property that could be sold for debt payment. Kyler lost the circuit court case and appealed to the Kentucky Court of Appeals. Ruling in favor of the circuit court, Justice Wheat commented: “Marriages between slaves have no legal effect.” Cynthia was again taken and sold to pay Kyler's debts.53

Despite these harsh realities, the men and women held in bondage created a life within the boundaries established by white society and slave law. This creation of a unique culture is the greatest and most far-reaching act of resistance in the period of African American slavery. One of the finest examples of this culture is the music and songs performed by slaves throughout Kentucky. On his family's Jefferson County hemp farm, Thomas Bullitt noticed a distinct difference between the types of songs the slaves sang in that they related to their work. At corn-shucking events, the songs were “sung rapidly on a high key with great vigor.” However, the songs performed as the slaves returned from a day working in the hemp fields were “slow, and if not melancholy in themselves, fell with pathos on the ear of the listener.” The songs were a reflection of the feelings and experiences of many slaves. Those of a religious nature spoke of heaven and the promise of deliverance and rest from the labors of this world. Many of the improvised songs included satire that would not be tolerated in everyday speech. One song heard in the Bluegrass region was the following:

Heave away! Heave away!

I'd rudder co't a yallar gal

Dan work foh Henry Clay

Heave away, yaller gal, I want to go.54

Music was an important part of the African American community in Kentucky. Numerous slaves and slave owners remarked on the spontaneity and prevalence of music at gatherings. Saturday evenings were times reserved for gatherings on farms, usually under the watchful eye of some whites. One slave remembered: “After their work in the fields was finished on Saturday, they would have parties and have a good time. Some old negro man would play the banjo while the young darkies would dance and sing.” Other celebrations surrounded holidays or were part of the annual farm rituals of planting and harvest. Eliza Ison of Garrard County recalled that at corn-shucking time “the neighbors would come and help. We would have camp fires and sing songs, and usually a big dance…. Some of the slaves from other plantations would pick the banjo, then the dance.” Former slave owner Thomas Bullitt wrote: “They loved to dance, and often danced without music except ‘patting'—that is, patting with the hands on the knees; and this they learned to do to perfection, giving and keeping ‘time’ to the dance. Such dances were usually by one or two negro men for the amusement of themselves and the others. To ‘pat Juba’ and to ‘dance Jim Crow’ were inspiring. ‘Once upon the heel tap / And then upon the toe / And ev'ry time I turn around / I jump Jim Crow.’”55

Contemporary white observers frequently misinterpreted the improvisation and rhythmic quality of African American music as evidence of the happiness of slave laborers. Slave music came to be viewed as evidence of the satisfaction that African Americans derived from their place in society. “[The songs] expressed at once the simple joy of life—of active life—and of rivalry in the work on hand,” wrote Thomas Bullitt. While apologists of slavery used the developing musical culture to justify their position, such labor songs provided repetition that sped up work and relieved the boredom of many of their tasks. But many of the same white observers were quick to note the unique quality of African American music compared to the other popular songs of the day: “Where they got them or who composed them I do not know…. Of one thing I feel quite sure—they were not the work of white men. They were the spontaneous expression of negro thought and feeling.”56

Saturday evening and harvest celebrations were not the only times that African Americans used music. Several Kentuckians commented on the singing of slave coffles as they moved through the state for sale in the Deep South. One observer was told that the singing was “an effort to drown the suffering of mind they were brought into, by leaving behind their wives, children, or other near connexions and never likely to meet them again in this world.”57 Another man heard the slaves slated for sale on a riverboat singing:

O come and let us go where pleasure never dies,

Jesus my all to Heaven is gone,

He who I fix my hopes upon.

His track I see and I'll pursue

The narrow road till him I view

O come and let us go,

O come and let us go where pleasure never dies.58

Those who refused to take part in the singing were whipped by the slave trader.

Music also speeded the work within the hemp factories of Lexington. A New England traveler heard some African American workers

drown out the noise of the machinery by their own melody…. The leader would commence singing in a low tone—“Ho! Ho! Ho! Master's gone away.” To which the rest replied with rapidity, “Ho! Ho!—chicken-pie for supper, Ho! Ho!—Ho! Ho!”…When they get tired of this, anyone who had a little fancy—and precious little would answer the purpose, would start something equally as sentimental; to which the rest again responded, at the same time walking backward and forward about their spinning, with great regularity, and in some measure keeping time with their steps.59

On the hemp farm, once the wagons were laden with the day's work and the walk back to the house began, “the negroes formed behind and beside it and began to sing. They kept singing until they got nearly in, when voluntarily they stopped.”60

In one unique situation, music became a skill to be marketed and an eventual escape to freedom. In 1844, a case was brought in Louisville against the owners of the steamboat Pike for carrying three slaves, without the owner's permission, from Louisville to Cincinnati, where they escaped. The case indicated that the owner, C. Graham, had given the slaves permission to live in Louisville with a free black named Williams in order to learn music and to travel throughout the area to perform. The three had an estimated value of fifteen hundred dollars each and were trained not only as musicians but also as dining-room servants. Graham complained that the loss of their services at the house he ran in Harrodsburg Springs would cost him five hundred dollars for one season. The freedom of movement allowed by the musical abilities of this trio led to their ability to move north and make their escape to Canada.61

Superstition existed in some segments of Kentucky slave society, but apparently it was not as prevalent as it was in other places of the South. Henry Bibb told of going to an old conjurer for a potion to change his owner's feelings of anger toward him to love. Bibb paid cash for a formula of cow manure, red pepper, and the white person's hair that he had to cook in a pot and then grind into a powder. Bibb was to sprinkle the powder in his master's bedroom and on his personal items, which he did during his normal chore of lighting a fire in the bedroom every morning and evening. But the results proved less than effective: “This all proved to be vain imagination. The old man had my money, and I was treated no better for it.” Most slave superstitions revolved around ghosts and evil spirits, and those closely mirrored the same folktales and beliefs held by whites.62

The question most debated by historians regarding slavery in Kentucky is whether it was more humane than slavery in the Lower South. It is true that, for the individual slave, daily life depended on how he or she was treated by the master or his overseer, and it is true that abundant anecdotes are available to support either cruelty or benevolence. Harold Tallant elucidated the enlightening theme that explains how Kentuckians were willing to discuss emancipation but refused to abolish slavery—they held fast to the necessary-evil defense. Today, as then, it is agreed that slavery was evil. Why was it necessary? Henry Clay answered several times that immediate emancipation would result in race war, anarchy, and dictatorship, which would destroy liberty. When he said this in a speech in Lexington on November 13, 1847, Frederick Douglass replied in a public letter: “How do you know that any such results would be inevitable? Where, on the page of history, do you find anything to warrant even such a conjecture?” Douglass argued that history, the voice of reason, and God's will revealed that it was always safe to do what was right. Where did Clay and his fellow Kentuckians get the idea that immediate emancipation was unsafe? There were many published arguments to that effect, but could it be that one day Clay looked into the eyes of one of his fifty slaves and saw the depth of suffering and resentment in his soul? Perhaps many Kentucky slave owners reflected on the resistance of their bond servants—expressed in many ways and realized with Thomas Jefferson that with slavery they had the wolf by the ears and could not safely hold on or let go.63