5

Half Horse and Half Alligator

War of 1812

Kentucky has an enduring legacy of military tradition dating back to the frontier; today, military and police snipers still use the term Kentucky windage, which initially referred to adjusting the Kentucky long rifle after the first shot to allow for wind and other variables. Shawnee warriors and Indians from other tribes attacked Kentucky settlers who depended on the militia for protection. Kentucky militiamen responded with preemptive raids deep into Indian territory; they took the initiative and went on the offensive, taking the war to the enemy and burning villages and destroying the winter supply of corn. Total war on the frontier gave birth to the legend that Kentuckians were superior fighters: sharpshooters with long rifles who seldom missed and “Long Knives” who fought ferociously in hand-to-hand combat. The Shawnee and other tribes of the Northwest developed a special hatred and fear of Kentuckians that increased during the American Revolution and reached its height in some of the most escalated retaliatory violence of the War of 1812. Legendary fame sometimes has a dark side, and for the Kentucky fighting man in the War of 1812 at times it meant being a special target; sometimes it involved the impossible challenge of measuring up to the heroic myth.1

On the American frontier, Indian fighting was total war characterized by the killing of noncombatants and prisoners of war and lack of respect for enemy corpses. In the intense conflict of the War of 1812 in the Northwest, an unconfirmed tale reported that, on the day of the Battle of the Thames, several Indian mothers drowned their babies because they had heard that Kentuckians slaughtered infants. Faced with the prospect of fighting Kentuckians, sometimes Indians would shout, “Kentucky! Too much!” and run away. According to a story told by a Frenchman residing in French-town, on the Raisin River in the Michigan Territory in the winter of 1812, an elderly Indian was smoking with a white man by the fireplace in the white man's home when news came that American soldiers were approaching. “Ho, the Americans come. I suppose Ohio men come, we give them another chase,” the Indian said, referring to a recent fight. But soon the Americans appeared, and, when the Indian saw that they were tall Kentuckians, he shouted “Kentuck!” picked up his rifle, and ran into the woods. The tale is unconfirmed, but that it was told indicates something about how Kentuckians were regarded. A Kentucky volunteer wrote early in the war: “The Indians at Piqua are panic struck at our coming. I am informed they will be off as soon as possible.”2

When Kentuckians participated in the campaign to recapture Detroit from the British and Indians in 1812, retaliatory violence escalated, and wounded Kentucky prisoners were murdered. The demand for retaliation was so great that Kentucky militia commanders warned their men not to kill captured enemy warriors. At the peak of the violence on the eve of the Battle of the Thames, when General William Henry Harrison's army of Kentuckians was about to avenge the Indian atrocities in the earlier Battle of the River Raisin, Harrison issued an order forbidding the murder of prisoners of war. “Kentuckians: Remember the River Raisin,” he said, but he went on to explain that it was to be only during the fighting—when the firing stopped, they were to refrain from taking revenge on their detested enemies. William M'Carty's history of the war stated that, when British general Isaac Brock issued a proclamation defending the use of Britain's Indian allies, he was referring to the Kentucky militia when he stated that the Americans had men in their camp who were “a ferocious and mortal foe, using the same mode of warfare” as the Indians.3

Kentuckians celebrated the reputation of the Kentucky state militia; they were honored that the Kentucky citizen-soldier had what historian Mary Ellen Rowe called “a fierce military tradition,” and they were proud that Kentucky soldiers and civilians were considered unparalleled in patriotism. Throughout the nation, the militiaman symbolized republicanism and public service; when summoned, he brought his musket and was willing to risk his life for the community. The militia was a fraternal organization that brought the people together for regular drills, reception of visiting dignitaries, and celebration of patriotic days, such as July 4 and Washington's birthday. An editorial in the Cincinnati Times during the Civil War praised Kentuckians for their legacy of militarism and patriotism. During the Kentucky gubernatorial election of 1863, a pro-Union editor in Cincinnati commended Kentucky for remaining true to Henry Clay's love for the Union and not seceding, and he challenged Kentucky voters to elect the Union Democrat Thomas E. Bramlette. “The country has never made a call upon Kentucky for men, or for money, but all that has been asked, and more, has been forthcoming,” he declared. “When the British invaded the infant State of Ohio, her people marched nobly to the rescue, and the bones of patriots whiten the plains of the Raisin, the Sandusky and the Thames to-day.” This was an exaggeration, but it demonstrates how great Kentucky's reputation had become; the reference to the bones whitening in the sun refers to the abuse of the dead bodies of Kentuckians in the War of 1812.4

The Western Citizen in Paris, Kentucky, concluded: “There is something in the very air of Kentucky which makes a man a soldier.” A Boston merchant on business in Kentucky in 1813 said that Kentuckians were “the most patriotic people [he had] ever seen or heard of.” He said that in New England it would be considered madness for a forty-or fifty-year-old man to volunteer to fight in Canada but that in Kentucky it was “considered glorious, as it really is.” Eastern journalists and politicians praised Kentucky as the example to emulate in military courage and patriotic enthusiasm. Niles' Register reprinted an editorial from the Albany, NY, Argus stating: “There are no people on the globe who have evinced more national feeling, more disinterested patriotism, or displayed a more noble enthusiasm to defend the honor and rights of their common country.” Several of the most prominent national heroes in the war were from Kentucky, and the reputation of the Kentucky militiaman as a legendary, romantic figure increased after the War of 1812. The song The Hunters of Kentucky on the Kentucky militia in the Battle of New Orleans declared that “ev-ry man was half a horse, and half an alligator,” and one of the song sheets was illustrated with two small militiamen standing at attention on each side and in the center a large ferocious monster, front half rearing, attacking horse and rear half alligator with huge, slashing tail.5

Throughout the diplomatic conflict with Great Britain that led to the War of 1812, Kentuckians demanded retaliation for violation of American honor and dignity. They discounted England's war with Napoleon and regarded British restrictions on American trade with France as directed against the United States, not France. They viewed Shawnee Indian chief Tecumseh's Indian confederacy as a threat but concluded that the British in Canada were behind Indian hostility. They believed that war with Britain was desirable and inevitable, and they welcomed it. In 1811, when Tecumseh's half brother Tenskwatawa, “The Prophet,” attacked the army of William Henry Harrison, governor of the Indiana Territory, and Harrison's men counterattacked and won the Battle of Tippecanoe, many Kentuckians were convinced that Britain ordered the attack as the opening blow in a war against Americans on the frontier. A broadside distributed in Kentucky declared: “War! War! War! The Blow is Struck.” Many Kentuckians believed that the British had to be driven out of Canada before peace could come with the Indians. Henry Clay said in the Senate on February 22, 1810: “The conquest of Canada is in your power. I trust I shall not be deemed presumptuous when I state, what I verily believe, that the militia of Kentucky are alone competent to place Montreal and Upper Canada at your feet.”6

During the war, the myth developed that Kentucky militiamen were more aggressive than those of other states and more willing to cross the international border into Canada. It is true that during the early part of the war, through the Battle of the Thames, many Kentuckians from counties north of the Kentucky River eagerly volunteered and invaded Canada without hesitation. One Kentucky mother approved when her fifteen-year-old son left for the war in 1813, saying: “I would despise him, if he did not want to go!” In some counties, nearly every available man volunteered, but, in others, men had to be drafted and served reluctantly. It was characteristic of militias to willingly defend their home state but hesitate to fight elsewhere, and, in the War of 1812, except for the northwestern theater, this was true for Kentucky men; they were extremely hesitant to go to New Orleans, for example. Since most of the fighting in the war was along the Canadian border, much attention was given to the fact that units of militia from Ohio, Pennsylvania, and New York balked at crossing the border during active campaigns. Kentuckians established such a reputation early in the war on the Detroit front that legend incorrectly portrayed them as always ready to go anywhere to defend the flag.7

Congress declared war on June 18, 1812, and Kentuckians celebrated jubilantly. The chief war hawk, Henry Clay, led all of Kentucky's congressional delegation in voting for war except Senator John Pope, who said that France was just as guilty as England and that the United States should have declared war on both. Pope's opinion made sense, but he was condemned throughout the state and burned in effigy in Nicholasville and Mt. Sterling. Every member of the state's congressional delegation volunteered for military duty except Clay and Pope. The people celebrated jubilantly with illuminations—lighting of homes and public buildings at night—and firing of cannon and muskets. “Kentucky seems ready to precipitate itself, en masse upon the British and their infernal allies the Indians,” reported the Kentucky Gazette. Henry Clay came home to Lexington in July 1812, and, when he saw how enthusiastic Kentuckians were for war, he was frightened by the passions that were unleashed.8

Kentucky was the key to the war in the Northwest because west of the Appalachians it had more residents than any other state and its economy was the most advanced. President James Madison relied on militias to fight the war, and in the West he relied on the Kentucky militia. Theodore Roosevelt wrote: “A militia force was the most brittle of swords which might give one true stroke, or might fly into splinters at the first slight blow.” This being true, the most fortunate development in Kentucky in the war was the election of the first governor of Kentucky, Isaac Shelby, to a second term. Shelby realized that the Kentucky militia was a brittle sword, and he was an outstanding leader who knew that, in reality, the state's patriotism had its limits. He was born near Hagerstown, Maryland, and, when he was about eleven, his family moved to western Virginia. When he moved to Kentucky in 1783 and settled in Lincoln County, he was famous for leading the assault that turned the tide of the American Revolution in South Carolina and earned him the sobriquet “Hero of King's Mountain.” He was sixty-one years old when elected governor in August 1812, and, at five feet, eleven inches in height, he had the appearance of a gentleman. Energetic and commanding, he stood out in a crowd, and at first he might seem haughty. But, in conversation, he was vivacious and overflowing with good feeling; everyone who knew him delighted in his company, and they said that he had no enemies. He had light hair, a high forehead, prominent nose, and large, blue eyes, uniquely piercing and stern but at the same time clear and tender—an early historian said that his eyes were “living flames.”9

Isaac Shelby realized that Kentucky militiamen would fight fiercely and successfully only under the right circumstances—otherwise they were unreliable. They required a respectable commander, a man of status and property whom they knew and were honored to follow. They needed to feel a sense of urgency and to have confidence that their community approved of their goals, and they needed to go on the offensive and return home shortly, preferably within sixty days. Shelby knew that they preferred riding in the cavalry to walking as infantry. The expectations the people of Kentucky had at the beginning of the war were as brittle as their militia. Kentuckians were confident that the British were so overwhelmed fighting Napoleon in Europe that they and their Indian allies would be easily and quickly defeated; Kentucky militiamen would capture Canada in one brief campaign and be back home on their farms within a few months. Shelby's axiom of war exactly suited the situation: “To march an army at a critical moment to act offensively is an object ever to be desired.”10

The first threat to the brittle sword of the Kentucky militia was that the War Department had named a stranger as commander of the Northwestern Army, and Shelby, the governor-elect, agreed with the outgoing governor, Charles Scott, that this must be changed. Scott had no problem recruiting the state's quota of two and a half regular army regiments and fifty-five hundred militiamen. Orders came from Secretary of War William Eustis that Scott was to send a detachment of eleven hundred men to unite with an army that was to reinforce Detroit. General James Winchester from Tennessee was the army commander. He was born in Maryland and fought in the Revolutionary War, rising to the rank of captain. He moved to Tennessee and fought in several Indian campaigns, winning promotion to brigadier general of the militia. He was a Tennessee state senator and speaker of the state Senate, and on March 27, 1812, he was commissioned a brigadier general in the regular U.S. Army. Even though Winchester was a veteran, the Kentucky militiamen did not respect him. Private Elias Darnall wrote in his journal: “Being a stranger and having the appearance of a supercilious officer, he was generally disliked.” Several said that they preferred General William Henry Harrison. The militiamen probably made their complaint at a review held in Georgetown, Kentucky, on August 16 as a farewell before reporting to the rendezvous at Newport. Governor Scott was present, and Henry Clay was the featured speaker. He reminded the men that Kentucky was famous for bravery and made the statement that became a watchword to inspire the men just before battle: “You have the double character of Americans and Kentuckians to sustain.”11

Clay, Scott, Shelby, and others felt uncomfortable that Kentucky was sending its contingent into the war under a commander they did not respect, and the matter took on urgency when General William Hull surrendered Detroit on August 16, the day of Clay's speech. Scott was near the end of his tenure, and when, on August 25, a few days before his term ended, he held a meeting with Shelby, Clay, and others, they agreed—on their own, without any authority from the War Department—to appoint William Henry Harrison as commander of the Northwest Army, including the Kentucky militia detachment. Harrison was the foremost military leader in the West and popular in Kentucky. When he was appointed, the Kentucky Gazette exclaimed: “Huzza for the hero of Tippecanoe.”12

President James Madison concurred with the change, and Harrison joined the army on August 31 between Lebanon and Dayton, Ohio, and, as he proceeded toward Canada, he divided his army into three columns. They were to march northward on three parallel routes and meet at the rapids on the Maumee River. The Kentucky militia regiments were united with a detachment of about 250 fellow Kentuckians in the Seventeenth U.S. Infantry to compose the left column of over 1,300 men under Winchester. Thus, the Kentucky militia had an overall commander they respected but an immediate commander they did not. Ironically, for the present campaign, Winchester displayed more initiative than Harrison. All three columns stalled under the frustrations of inadequate roads and heavy rains, snow, and insufficient supplies. Alarmed that it was taking so long, Shelby, now as governor, dispatched riders galloping from Frankfort with letters encouraging Harrison to march on to Detroit. Winchester's column reached the farthest, arriving on the upper Maumee River by October, but there they camped for about two months.13

Meanwhile, without authority from the War Department, Shelby organized a diversionary raid on Tecumseh's allies in Indiana and Illinois that was supposed to support Harrison. It was the infamous Hopkins Raid, named for its commander, Kentucky congressman and militia major general Samuel Hopkins. In organizing the raid, Shelby complied with several of the basic requirements for militia success: the term of service was thirty days, the volunteers were mounted, and they respected their fellow Kentuckian Hopkins. But there was no sense of emergency or feeling among the people of Kentucky that the Indians of the prairie were a threat to the state or to Harrison's army, and Hopkins proved to be a failure as a military leader. The two thousand raiders were inadequately organized, and discipline broke down. Deep into Illinois, the guides got lost and could not find the Kickapoo and Peoria villages. The Indians found the raiders, however, and set the grass on fire around them. The raiders survived the fire, which was at night, but the next day, with their morale broken, the men in the ranks voted unanimously to withdraw. Hopkins wanted to continue, but, facing mutiny, he could not. The raid failed; Shelby and a court of inquiry exonerated Hopkins, but the Kentuckians were very disappointed.14

General James Winchester surprised people by reaching the Maumee River first and then again by taking the offensive before Harrison. In December, he had his nearly thirteen hundred Kentuckians build sleds to move their baggage down the frozen river to the Maumee River rapids, near Grand Rapids, Ohio, today, where they were to meet Harrison and the other two columns. On December 30, they started, but soon the horses gave out, and the men took turns in six-man teams pulling the sleds. This was challenging on the ice, and on January 2, 1813, it started snowing, the storm lasting for two days and nights, accumulating two feet and making the sledding more difficult. They trudged on and on January 10 arrived at the rapids, where they erected a fortified camp on the north bank. They found corn to eat, and warm clothing made by women in Kentucky arrived on January 15. Morale improved, and word spread through the camp that there was abundant food and shelter thirty-five miles to the northeast in the small village of Frenchtown, the present-day Monroe, Michigan, lightly guarded by fifty Canadian militia and one hundred Indians. Winchester met with the officers, and they discussed the fact that Frenchtown was only eighteen miles southwest of Fort Malden, where there was a strong enemy force. Should they wait for Harrison before moving? No, the officers favored an immediate attack, so on January 17 Colonel William Lewis marched with 550 men, and Colonel John Allen followed with 110.15

When the raiders came within three miles of Frenchtown, the next afternoon Lewis formed them in battle order and had the battalion commanders read his battle order. “Soldiers!” he said, “your ancient enemy is before you. The wrongs that he has inflicted upon your country are fresh in your memory. That country calls upon you this day to vindicate her honor…. In the hour of battle remember what the Patriot Orator said to you at Georgetown…and all will be well.” They crossed the frozen Raisin River at about three o'clock in the afternoon and skirmished with the smaller force in the village, driving the enemy into the woods to the north and capturing the town. The Kentuckians lost thirteen men killed and fifty-five wounded. When a burial party went to the battlefield the next day, they found that twelve of the thirteen Kentucky dead were scalped, stripped, and left naked in the snow. An unconfirmed statement, written three years later, stated that, during the fighting, the militia tore an Indian's body “literally to pieces.”16

That night, while a courier went toward Winchester's headquarters with Lewis's report, the men feasted on apples and cider and plentiful food in the town and felt completely warm for the first time in weeks. When Winchester received the report, he awakened to the danger—his detachment was divided in the vicinity of a strong enemy. Immediately he headed to French-town with about 250 men, followed some distance behind by another 250, Kentuckians of Seventeenth U.S. Infantry under Colonel Samuel Wells. Winchester arrived at the village on the morning of January 20 and camped his men beside the Kentuckians already there, with the Raisin River in their rear and within a picket fence or stockade that surrounded the houses of the thirty-three families of Frenchtown in a semicircle. Wells arrived at about three o'clock that afternoon, and there was no space for his regiment inside the fence. Therefore, Winchester posted the regulars outside the fence in an open field to the right. Winchester should have ordered the regulars to throw up a breastwork because they were totally exposed to a frontal assault and nothing anchored their right flank. Winchester had about one thousand men in the village, but they were so vulnerable that he said later that he would have withdrawn had he not wanted to leave the fifty-five wounded men behind. Furthermore, the Seventeenth Infantry had only ten rounds of ammunition per man.17

The next day, January 21, civilians brought reports that a British force was nearby; Winchester and his men went to sleep that night expecting an attack the next morning. Winchester posted sentries at the edge of the camp but none along the road the enemy was expected to use. At 6:00 A.M. on January 22, the men awoke to the ominous sound of British drums in the woods to the north. They checked their rifles and were ready to fight when they heard the “crack” of a musket fired by one of their sentries. It was a warning shot, but it struck the head of a British soldier in the advance and killed him instantly. The British were led by Colonel Henry A. Proctor of the Forty-second Infantry Regiment, commander at Fort Malden. He had camped five miles away during the night, and he had plentiful ammunition, three small cannon, 597 British regulars and Canadian militiamen, and over 600 Indians led by the Wyandot chief, Roundhead. He deployed his artillery and regulars in the center and the militiamen and Indians on the left and right flanks.18

The British attacked, and the Kentucky militia behind the fence held firm, but the Seventeenth Infantry in the field was totally exposed to artillery and musket fire, and after twenty minutes it retreated, and the men were surrounded by Indians who had rushed in on their exposed right flank. The Indians took a few prisoners but shot and scalped over one hundred Kentuckians within a few minutes. Colonel Allen was killed; Winchester and Lewis were stripped and taken to Roundhead, who sent them to Proctor's headquarters, where Winchester surrendered his entire command. Major George Madison, in charge of militia inside the fence, had repulsed several assaults and was still fighting. At one point he called for a volunteer to set fire to a tall barn 150 yards toward the enemy line. He feared that the British might use the barn for sniper fire over the fence. Ensign William O. Butler volunteered, raced across the field of fire, set the barn on fire, and returned safely but with clothing shredded with bullet holes. He survived to fight in the Mexican War and become a candidate for governor of Kentucky in 1844. Finally, a British soldier appeared with a white flag and a message from Proctor that Winchester had surrendered. Madison feared that, if he complied with the surrender, the Indians would massacre his men as prisoners. Only after Proctor promised that all prisoners would be safe did Madison have the men stack their rifles.19

Madison surrendered about midday, and immediately Proctor began making arrangements to withdraw. He ordered that the eighty wounded Kentuckians be left behind in houses in Frenchtown until sleighs could be sent for them. There was tension in the air, and Madison could see anger in the faces of the Indians who were milling about and seemed to be waiting for the British to leave. He was chilled to the bone when he saw that Proctor assigned only four or five regular soldiers to remain in Frenchtown to defend the wounded prisoners. He gathered the walking prisoners as close together as possible and attempted to keep them together as the march began. A short distance out of Frenchtown, individual Indians and Indians in small groups sprang out of the woods and assaulted the prisoners, beating, tomahawking, and knifing several and dragging others away.20

That night in Frenchtown, Indians looted and found whiskey and in a drunken state began attacking the wounded prisoners, tomahawking them in their beds, scalping them, and dragging them outside, where they were stripped and some decapitated. They set fire to two of the houses where prisoners were lodged, and tomahawked the men who attempted to escape. An estimated forty to sixty-five of the wounded men were murdered, and their naked, frozen bodies were left on the snow. Six months later, Colonel Richard M. Johnson's mounted regiment marched through Frenchtown and, according to Robert B. McAfee's journal, discovered the bones of thirteen or fourteen of the men scattered along the road for three miles, “the Indians having dug them up. (they cry aloud for revenge!).” Johnson had his men bury them. Almost four months after that, some of the same or additional bones were whitening in the Michigan sun, and, on October 15, Governor Shelby sent a party to bury them. In the fighting, on the march to Fort Malden, and in the massacre on the Raisin River, the American force lost at least four hundred men killed.21

Battle of the River Raisin, January 22, 1813. Lossing, Pictorial Field-Book of the War of 1812 (1869), courtesy Kentucky Historical Society.

Eleven days after the battle, a courier arrived in Frankfort in the evening when Governor Shelby and many others were at the theater. They called Shelby out, and the courier handed him General Harrison's letter reporting the defeat and massacre. The news spread immediately through the audience, and people began quietly walking out and leaving for their homes. Some probably had relatives in the battle because eighty-eight militiamen from Franklin County were in one of the companies involved. Nearly everyone knew at least one of the men, and the entire county was grief stricken. “You see fathers going about half distracted, while mothers, wives and sisters are weeping at home,” wrote an observer. The Kentucky legislature was at the end of its session and planning to adjourn without any other action on February 3, the day after the news arrived. Instead, it convened for business and passed a bill authorizing three thousand militiamen for a term of six months' service.22

“The melancholy event has filled the state with mourning, and every heart bleeds with anguish,” wrote Shelby to Harrison. Transylvania University students wore black crepe armbands for thirty days. When the honeysuckle bloomed, the survivors began coming home individually and in small groups; in Frankfort, militia officials arranged to fire a cannon on the capitol grounds to announce an arrival. Families rushed into town from all directions, hoping to see their son or husband. When Lieutenant Peter Dudley returned to Frankfort, he announced that he was recruiting a company to avenge the dead, and one hundred men volunteered immediately. Kentuckians gradually absorbed the news, and, analyzing the war, they agreed that an early conquest of Upper Canada was impossible.23

Dudley's successful recruiting in Franklin County was unusual; Governor Shelby seemed almost overwhelmed with the feeling that, on the command level, he was alone. His confidence in General Harrison dissipated when the general failed to move rapidly on Detroit, and Winchester's failure in the Battle of the River Raisin seemed to confirm that only Kentucky officers could lead Kentuckians. He had no confidence in Secretary of War John Armstrong, who replaced Eustis on January 13 and who proposed the ridiculous idea of replacing the militia with a large regular army. Shelby had never had confidence in the federal government to adequately address military requirements in the West, but now he had nowhere else to turn. He agreed with most Kentuckians that land operations could not defeat the British in Upper Canada until the navy took control of Lake Erie. He wrote to administration officials pleading for that and promising that such a victory would restore hope to the people of Kentucky.24

Shelby was hoping for a lift in morale to encourage recruiting because men were not responding to the call of the General Assembly for three thousand militiamen after the Battle of the River Raisin. Kentuckians had lost confidence in the Madison administration, and they were not eager to participate in another disaster. Then came an urgent request from Harrison for a new contingent of Kentucky men to help defend against Colonel Proctor, who might attack any day. Harrison had constructed the new Fort Meigs on the Maumee River in northern Ohio, and he was defending it and the U.S. border with only one thousand men. Shelby responded, but he had to use a draft, and the draftees and substitutes enrolled were not of the same quality as the men of 1812. He finally obtained one thousand men and sent them forward under General Green Clay, second cousin of Henry Clay and a prosperous planter and political leader from Madison County. By the time Clay's force approached, Proctor was besieging Fort Meigs with a force more than twice the size of Harrison's. Proctor had five hundred regulars, five hundred Canadian militia, and about twelve hundred Indians led by Roundhead and Tecumseh. He had shelled the fort for four days with cannon from both sides of the river, with considerable psychological impact on Harrison and the men in the garrison but little physical effect.25

As Clay approached, floating down the river with his men in eighteen flat-boats, he sent Harrison a message that he was only two hours away. Harrison replied with orders for Clay to divide his force and launch a raid on the artillery position on the north bank opposite the fort. Clay was to have the raiders capture and spike the cannon and quickly return to their boats and proceed to Fort Meigs. It would have been extremely risky to attempt such a raid with regular soldiers; with militia it was even more hazardous. Clay obeyed and sent Lieutenant Colonel William Dudley with eight hundred men in twelve boats to spike the artillery. Clay and the other four hundred landed, fought their way through the Indians around the fort, and arrived safely with over sixty casualties. Dudley surprised and surrounded the British batteries and captured the guns, and he was ready to withdraw in success when Indians fired on his men from the woods on their left and one of his companies went in pursuit. Dudley had not authorized this, but he pushed forward with the rest of his men, down the river toward Proctor's main camp and into an ambush the Indians had organized. Suddenly, the left column of raiders was caught in an Indian cross-fire, and those on the right ran head-on into a strong detachment of Proctor's army and additional Indians. The Kentuckians fought but were outnumbered and overwhelmed. Dudley was killed, and the entire force that participated in capture of the artillery was either killed, wounded, or captured. Of his 800 men, only the 150 men who stayed with the boats escaped.26

Proctor now had an opportunity to obey international law and provide for the safety of another group of Kentucky prisoners of war, but tragically he failed again. He had the prisoners placed under a guard of fifty British regulars and marched a few miles downriver to old Fort Miami, an American Revolutionary War fort that was in ruins but was used as a British supply depot. The number of guards was totally inadequate, and, as the column marched, Indians ran alongside, whooping, taunting and cajoling, and robbing the prisoners of watches, money, and clothing. At the entrance of the fort, Indians formed a gauntlet and, yelling at the top of their voices, slashed at the prisoners with knives and tomahawks. When the prisoners reached the interior of the fort, Indians climbed on the walls and began shooting them with their rifles. Private Russell of the Forty-first Infantry Regiment attempted to stop the killing, and an Indian shot and killed him. At least forty men had been killed when Tecumseh came galloping into the fort and ordered a halt to the shooting. He told the murderers that they were cowards. As soon as he saw Proctor, he shouted: “Begone! You are unfit to command. Go and put on petticoats!” The raid and massacre were on May 5, and on May 9 Proctor closed the siege and withdrew, leaving Harrison still in command of Fort Meigs.27

Dudley's Defeat. Lossing, Pictorial Field-Book of the War of 1812 (1869), courtesy Kentucky Historical Society.

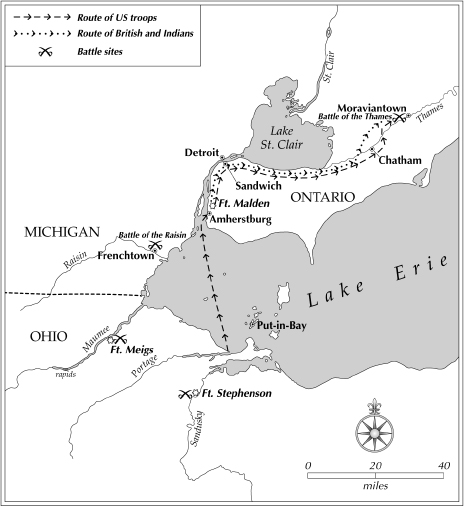

In Kentucky, the news of Dudley's defeat seemed almost unbearable. Again a Kentucky militia force had been defeated and Kentucky prisoners murdered. Shelby's reaction demonstrates how war brings out the strength of character in some leaders. He realized that it was time for extraordinary endeavor—volunteering was down, and the people were discouraged, but he knew that Kentucky militiamen could be successful if they were led properly. He was sixty-two years old, but he decided to lead the men himself—he would take to the field and go with the men to Canada. Out of the darkness and gloom, he rose to the occasion and realized his finest hour—on July 31, 1813, he released a widely circulated handbill calling one more time for men, for a new army of Kentucky mounted volunteers. “I will lead you to the field of battle,” he said, “and share with you the dangers and honors of the campaign…. Fellow Citizens! Now is the time to act; and by one decisive blow, put an end to the contest in that quarter.” The term of enlistment was sixty days, and the rendezvous was in Newport in one month. Men responded enthusiastically in some counties, but he had to order a draft for fifteen hundred men south of the Kentucky River.28

Governor Shelby had been phenomenally unlucky to this point in the war, but, about the time that he issued his draft order, his luck changed. In his proclamation, he stated that he believed that the Madison administration was determined “to act effectually against the enemy in Upper Canada.” Now came news that Congress had passed legislation providing more adequate funding, and then newspapers reported that President Madison had requested an embargo on shipping. A few days later, the embargo failed in Congress, but the fact that Madison requested it was a positive sign. And, while drafting and volunteering were under way, thrilling news came of the most heroic story of the war involving a Kentuckian and one of the most valiant of the entire war—a twenty-one-year-old regular army major and his 160 regular soldiers from Kentucky had defeated General Proctor and the army of the Battle of the River Raisin and Dudley's defeat!29

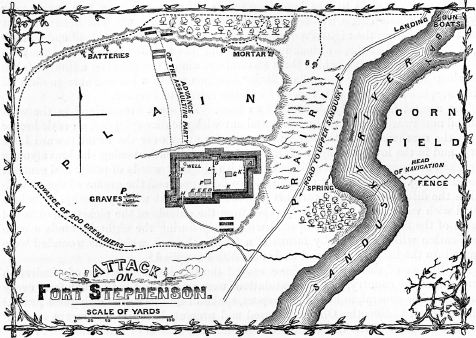

The account was like something from a romantic novel, but it was true, and it came when Kentucky and the nation needed a lift in morale. Proctor had besieged Fort Meigs a second time, and withdrawing he decided that, rather than returning to Canada empty-handed again, he would go for a sure thing by capturing tiny Fort Stephenson ten miles from Lake Erie up the Sandusky River. He had almost fourteen hundred men, including Indians, and gunboats and three six-pound cannon—it seemed like attacking a mouse with an elephant. Harrison learned about the plan and, assuming that the fort was already lost, ordered Major George Croghan to burn it and retreat. Croghan refused and answered: “We have determined to maintain this place, and by Heaven, we will.” He was well aware that a major could not disobey his commanding general's direct order, and, therefore, he went in person to consult with Harrison at Fort Meigs and convinced him to withdraw the order.30

Proctor and his army landed on August 2, 1813, and he ordered the disciplined Forty-first Infantry to lead the assault, expecting that they would easily capture the fort. Croghan had only one cannon, “Old Betsy,” and, when the Forty-first came within range, Old Betsy commenced firing nails and grapeshot into their ranks. Then the Kentucky sharpshooters opened with their rifles, and Proctor reported that it was “the severest fire I ever saw.” The Indians quickly ran away, but the Forty-first fought bravely for two hours, losing every officer and one-fifth of its men before Proctor called off the attack and sailed back up the river. Croghan had one man killed and seven wounded. The victory had no strategic significance, but it was the psychological turning point of the war. Historian Mary Ellen Rowe wrote: “Finally, an American force, and one outnumbered perhaps three to one, withstood a direct assault by British regulars and repulsed them decisively. Americans all over the Northwest celebrated the victory.”31

Attack on Fort Stephenson. Lossing, Pictorial Field-Book of the War of 1812 (1869), courtesy Kentucky Historical Society.

Shelby's luck had, indeed, changed. Croghan's victory came in time to raise morale and encourage recruiting before the rendezvous in Newport. The governor did not know how many men would report, and he was much encouraged when he met thirty-five hundred volunteers in Newport. Then, as they marched north through Ohio, he received even more wonderful news—on September 10 the military turning point of the Northwest came with Oliver Hazard Perry's victory over the British fleet on Lake Erie. This was what Shelby and Kentuckians had wanted all along, and now it ensured that the present Kentucky land expedition could invade Canada. When Harrison learned of Perry's victory, he prepared for the invasion by establishing new headquarters on Lake Erie near the Portage River where his army could use Perry's fleet to cross to the Canadian shore.32

Finally, everything was coming together. Shelby joined Harrison on the Lake Erie shore on September 15, and into the camp rode Colonel Richard M. Johnson and his regiment of beautifully mounted Kentucky volunteers. Harrison sent Johnson moving by land toward Detroit and used Perry's fleet to transport the rest of his army on September 27 to the landing beach near Amherstburg, Canada, and from there they marched to Sandwich across the Detroit River from Detroit. Two days later, he sent a force to occupy Detroit. Johnson's regiment reached Detroit on September 30 and ferried across the river to Sandwich on October 1. The Americans landed in Canada without opposition. When Perry achieved naval dominance on Lake Erie, Proctor realized that he could no longer hold the Detroit frontier, and, therefore, he withdrew from Fort Malden and the coast on September 27, retreating slowly along the north bank of the Thames River. Now that Harrison's main body was united and in Canada, it was time to pursue and destroy Proctor's army. Therefore, Shelby could hardly believe it when Harrison suggested that he wanted to delay because most of his regulars' equipment had not arrived. Shelby and his officers told him that they refused to wait, and they forced him to move on October 2 without the equipment. At that moment, the impatience of Shelby and the Kentucky militia served the nation well; if Harrison had delayed, Proctor might have escaped.33

Shelby was succeeding in taking advantage of the strengths of the militia, and he had never seen morale this high in a military force. Partly it derived from Perry's victory dramatized by the voyage across Lake Erie in boats and ships, four of which were captured from the British fleet and now had the stars and stripes on their masts. Perry's sailors were the heroes of the hour, and it filled a man with self-confidence to be with them and identify with their great and total victory. Perry's success infused the entire land expedition with momentum and a spirit of success when Perry himself joined the march as an aide to General Harrison. Finally, they were invading Canada and taking the initiative against Proctor and his regulars. And another thing that infused the command with esprit de corps was the presence of Richard M. Johnson and his men—one of the best-trained militia regiments in the war. He was commissioned colonel in the regular army, and he recruited the regiment himself under authority of the secretary of war by publishing a broadside on March 23, 1813, two months after the Battle of the River Raisin. He declared that the purpose of the regiment was to win honor and glory by avenging the massacre of fellow “countrymen and friends, by the savages, under British influence.” The men were to dress in a black hunting shirt and black neck-scarf and bring a strong horse, a rifle or musket, tomahawk, and butcher knife, and, if possible, a sword and pistol. The term of enrollment was four months. Johnson's call was directed at gentlemen of means who could afford to equip themselves, and the result was an elite band of fighting men who were self-confident and proud. Johnson and his regiment personified Kentucky's ideal in the war; when he became a legendary hero, a popular poem designated him the “perfect pattern of heroic worth.”34

Few things were simple in the War of 1812, and Johnson and his men had come to this moment in a roundabout way. The men had rendezvoused at Newport on May 22, 1813, and those who lacked arms were furnished them. They arrived at Harrison's headquarters on May 31, 1813, and for over thirty days Johnson enforced a strict training routine of drills, parades, and lengthy patrols. It was during this period that he sent the burial detail to Frenchtown. On July 5, Johnson received orders from Secretary of War John Armstrong to march four hundred miles into Illinois to reinforce a post there. This was an incredible order, a waste of resources, but Johnson brought the regiment home to Kentucky to prepare for the long march. He dispersed the men and was supposedly still preparing for Illinois when, on July 30, he received orders from Harrison to join the invasion of Canada.35

Johnson was a friend of Thomas Jefferson's, and he identified with small farmers struggling to pay their debts; he was a champion of the common man who later, after the election of 1824, became an ardent supporter of Andrew Jackson. He would be eulogized as “the beau ideal of the soul and the chivalry of Kentucky.” He was born October 17, 1781, in the frontier settlement of Beargrass, later named Louisville. His family moved to Bryan's Station in Fayette County a few months after he was born. He attended Transylvania University, studied law, and opened a law practice in Scott County. He was elected in 1804 to the state legislature and in 1807 to the U.S. House of Representatives, where he had been one of the war hawks and where he was still a member. With friends he was gentle, personable, and kind-hearted, but he loved to fight, and one could see it in his appearance. The English author Harriet Martineau observed: “His countenance is wild, though with much cleverness in it; his hair wanders all abroad.” When he was vice president of the United States, he heightened the effect of his flaming red hair by presiding over the Senate wearing a red vest. He had a thundering voice and was an eloquent speaker who appreciated the rhythm of words. Campaigning for reelection as vice president, he said of his War of 1812 commander and the presidential nominee of the opposing party, William Henry Harrison: “The history of the West is his history; for forty years he has been identified with its interests, its perils, and its hopes.” After Henry Clay, he was the most popular statesman in Kentucky, and, when he spoke, he touched the soul of his audience.36

Wearing his black hunting shirt and riding his beautiful white mare along the north bank of the Thames River that day, Johnson would cross the threshold of fame and become the “tried patriot warrior.” He and his American comrades had the advantage of outnumbering the enemy over two to one. General Harrison had left many men on garrison duty in Detroit and posts on the Canadian shore, but he had 3,120 men: 120 regulars, 2,000 Kentucky militiamen under Shelby, and 1,000 Kentucky militiamen under Johnson. Colonel Proctor had fewer than 500 regulars and about 1,000 Indians. By October 4, Harrison's advance was threatening Proctor's rear guard, and, on October 5, about two miles west of Moraviantown, Proctor carefully selected a position to make his stand. The road ran along the river, which anchored his left while a large swamp with trees and heavy undergrowth covered his right. In between was a partially wooded strip of land from two to three hundred yards wide with a small swamp in the center and heavier woods toward his rear.37

Colonel Proctor had been in the British army all his life, and he was well schooled in the value of the infantry volley fired on the defensive against an assault. But he had been in Canada since the beginning of the war and had learned to adapt. British army training directed that he should form his regular infantrymen in close order where the two ranks could alternate firing and loading and lay down a deadly stream of musket balls that would usually repel any frontal assault. Instead, Proctor arrayed his men in open order in two lines in the woods for protection. They were deployed more like Indians or American militiamen than British regulars. Perhaps he was adjusting to the fact that he was outnumbered, but the deployment may have added to the demoralization of his men. They had not eaten for some time, and they waited in line of battle for three hours, during which Proctor shuffled and reshuffled them. Proctor's position had the advantage that his flanks were entirely secure, but the small swamp in the center made it necessary to divide the battle line, and this would have made it difficult to shift for reinforcement of a weakened part of the line. Proctor expected his regulars to halt the advance of the American infantry and set them up for the coup de grace of his plan—in the almost impenetrable swamp on his right he positioned Tecumseh's warriors, who were to fire into the American left flank, rush to Harrison's rear, and capture the retreating Yankees as they ran away toward Detroit.38

Invasion of Canada and Battle of the Thames, October 5, 1813. Dick Gilbreath, University of Kentucky Cartography Lab.

Battle of the Thames. Lossing, Pictorial Field-Book of the War of 1812 (1869), courtesy Kentucky Historical Society.

The sun was shining, and it was midafternoon when Harrison deployed his force to attack. Shelby's men were to fight dismounted, and Harrison arrayed them and his regular infantry in two lines across the field, with a third line in reserve. Johnson's men were to fight mounted, and he placed them on his left with orders to flank the Indians. Then, in his greatest moment as a tactician, he kept thinking about Proctor's open ranks and how the veteran British regulars were behind trees. One of the greatest abilities of a commander is discretion, the ability to look at an enemy force and decide whether an attack will succeed. Harrison used discretion and changed his plan: “I therefore determined to refuse [i.e., defend] my left to the Indians and to break the British lines at once with a charge of the mounted infantry. The measure was not sanctioned by any thing that had been seen or heard of, but I was fully convinced that it would succeed. The American backwoodsmen ride better in the woods than any other people. A musket or rifle is no impediment to them, being accustomed to carry them on horseback from their earliest youth.” Harrison shifted his infantry to the rear in reserve, where they could prevent a flanking attack by the Indians, and ordered Johnson's mounted riflemen to assault the British line.39

When Johnson formed his regiment for the attack, he saw that the area between the small swamp and the river was too narrow for his men and horses. Therefore, he divided them into two battalions, sending his brother James leading the battalion adjacent to the river, and he himself leading the other half against the British lines on the left. Harrison directed that Johnson was to walk the horses forward until the enemy fired their first volley and then order the assault. When the horsemen got within range, the British fired, and, with smoke rising through the trees, Johnson shouted: “Forward, Charge!” The mounted Kentuckians spurred their beautiful horses into a run, and suddenly a cry arose from their throats and from the infantry standing in reserve. It was a thundering, intense chant that resounded through the trees and was repeated and repeated with ever-increasing resonance and volume: “Remember the Raisin! Remember the Raisin!”40

Firing their rifles, Johnson's horsemen rode through the British lines, between the infantrymen in a mounted charge like Confederate colonel John Singleton Mosby used later in the Civil War. In the British rear, they turned about and formed a loose net to capture the British as they retreated. Harrison's report said: “In one minute the contest in front was over.” Actually, it took about ten minutes, and some of the British men fired two or three shots. One soldier on the British right recorded that he fired only once. However, when Johnson's battalion on the left reached the British rear, the Indians struck with galling fire from the large swamp. Johnson ordered his men to dismount and return the fire, but the Indians were so well covered they had the advantage. Therefore, to lessen the number of casualties, Johnson adopted the desperate tactic of the “Forlorn Hope,” in French, enfants perdus or “lost ones.” He called for twenty volunteers to rush the Indians and take their fire, enabling the rest of the men to close on them before they could reload. This meant almost certain death, but twenty men immediately came forward, including the man Johnson placed in command, William Whitley, a sixty-four-year-old pioneer who was one of the earliest settlers of Kentucky. Johnson named Whitley as commander, but he led them himself, still mounted on his white mare, which made him an obvious target. At the edge of the swamp, they were struck with withering fire, and Whitley and fourteen others were killed and four wounded. Only one of the Forlorn Hope escaped unharmed.41

Johnson ordered the rest of his men to advance on foot into the swamp, and Shelby sent a detachment of reinforcements. The Kentuckians fired one shot and closed with the Indians in hand-to-hand fighting, with Johnson in the lead. He was struck by five bullets and was wounded in the thigh, hip, left hand, and left arm, wounds that would cause him pain for the rest of his life. Pushing into the swamp, his horse was hit the seventh time and fell dead under him, and at that moment an Indian ran toward him with his tomahawk raised to strike. Johnson killed the man with his pistol. He did not know the Indian, but some of his men said he was Chief Tecumseh. It is certain that Tecumseh was killed in the fight, but whether the Indian Johnson shot was Tecumseh has never been determined. Proctor escaped, but his carriage, hat, sword, and trunk of letters were captured.42

The victory was complete: twelve British regulars were killed, twenty-two wounded, and over six hundred captured. The enemy army of the Battle of the River Raisin and Dudley's Defeat was destroyed. Every cannon of Proctor's army was captured, including three captured from General John Burgoyne in 1777 and retaken by the British in Detroit. American battle flags captured at Detroit, the Battle of the River Raisin, and Dudley's Defeat were recaptured. The victory, following Perry's on Lake Erie, gave the United States temporary control of Upper Canada, crushed Tecumseh's confederacy, and in effect ended the War of 1812 in the Northwest.43

When the news came home to Kentucky, the people were almost beside themselves; they began celebrating with poems, speeches, and legendary stories and continued commemorating the victory for the next fifty years. President Madison commended Harrison, Shelby, and Johnson for delivering “a decisive blow to the ranks of the enemy.” Five years after the battle, Whitley County, Kentucky, was named for Whitley, and Isaac W. Skinner's Kentucky; a Poem, published in Frankfort in 1821, compared him to Homer's Hector. Congress presented gold medals to Shelby and Harrison and a ceremonial sword to Johnson. Within a few years, Johnson became more and more identified as the one who killed Tecumseh. When Andrew Jackson entered his second term as president, Johnson's friends started promoting him for the Democratic presidential nomination in the election of 1836. His friend William Emmons published a campaign biography, The Authentic Biography of Colonel Richard M. Johnson, claiming that, in the Battle of the Thames, Johnson was shot twenty-five times, and stating that he probably killed Tecumseh. In 1834, Richard Emmons's play Tecumseh, of the Battle of the Thames was popular, and in Johnson's campaign in 1836 his supporters chanted: “Rumpsey dumpsey, rumpsey dumpsey, Colonel Johnson killed Tecumseh!”44

Johnson never won the presidential nomination, but the Democratic convention in Baltimore in 1835 nominated him for vice president, and one of the convention speeches lauding him as the nominee labeled him “Old Tecumseh.” In the campaign, he was frequently called “Old Tecumseh” and “Hero of the Thames.” The Battle of the Thames loomed large in the 1836 campaign as Harrison was one of the Whig Party nominees opposing Democrats Martin Van Buren and Johnson. During Johnson's campaign, he accepted an invitation to speak to a large crowd in Cincinnati. When he paused for a moment in his discussion of national issues, a heckler in the rear of the hall shouted: “Were you at the Battle of the Thames?” He answered: “I was, and what of it?” “Are you the hero of that battle?” “That's a very singular question,” Johnson said, and he launched into a description of his role in the battle. He told how during the fighting with the Indians in the swamp he had been wounded five times and his horse had taken six bullets. Moving deeper into the marsh, he jumped his horse over a log, and the horse was hit the seventh time and collapsed, pinning Johnson's leg so that he could not dismount when a tall, handsome Indian approached with his tomahawk raised, ready to throw. “I pulled out a loaded pistol from my holsters and shot him. They say it was Tecumseh I shot. I care not, and I know not. I would have shot the best Indian that ever breathed under such circumstances, without inquiring his name, or asking the ages of his children.”45

At that point he paused, and the audience broke into “a deafening roar of applause.” Then a second heckler, obviously not a Democrat, shouted: “Where was General Harrison then?” Johnson looked the querist dead in the eye, and, lowering his voice to the tone of a volcano about to erupt, he replied: “He was in the very spot where the Commander-in-chief ought to have been.” He was amid the whizzing bullets ready to charge with the dismounted men if required, Johnson said. Then raising the volume of his voice, he thundered: “No one must attempt to tickle my fancy by intimating, in my presence, that General Harrison is a coward!” His popularity in Kentucky continued, and in 1843 Johnson County was named for him.46

After the Battle of the Thames, Kentuckians calculated that they had done enough, and for the rest of the war they were reluctant to volunteer. This contradicted the legend of Kentucky's model patriotism and was embarrassing when the British invaded New Orleans. The army that defeated Napoleon was invading the United States, and Louisiana governor William Claiborne and General Andrew Jackson pleaded with Governor Shelby to send reinforcements. Secretary of State James Monroe assigned Kentucky a quota of twenty-five hundred militiamen, and Jackson expected Kentucky to live up to its reputation. Facing the crisis of his career, Jackson was seriously disappointed. First, the Kentuckians were late arriving. He had already fought the invaders twice—first with a night attack and then with an artillery duel—when finally on January 2, 1815, his friend General John Adair from Mercer County, Kentucky, appeared and reported that a force of twenty-two hundred Kentucky militiamen were on the way and would arrive within a few days. Adair said he had to mention, however, that only one-third of the men were armed “and those very indifferently.” Jackson answered: “I don't believe it! I have never seen a Kentuckian without a gun and a pack of cards and a bottle of whiskey in my life.” Behind this humorous quip was deep disappointment: Jackson had hoped that Kentucky would send men ready to fight, and he felt insulted that the state sent him unarmed men; it violated the militia tradition to send men into the field without arms. He wrote Monroe that he had no guns to give the Kentuckians and that, therefore, they were useless to him. The Kentucky men arrived in New Orleans on January 4, 1815.47

Jackson was never one to emphasize spit and polish, but he felt embarrassed over the appearance of the Kentucky militiamen because they marched into New Orleans looking like an army of destitutes. The weather was chilly, but many were dressed in rags, and with no weapons to carry many used both hands to hold their pants up and their shirts together. They had no tents, and many had no bedding or cooking equipment. When Governor Shelby received Monroe's order in October, he complied by calling out twenty-five hundred men and ordering them to go down the Ohio and Mississippi rivers on boats to New Orleans. But men from the more prosperous families generally refused to report, and Shelby resorted to a draft; many of the men were, according to him, “drafts & substitutes from amongst the poorer kind of citizens.” Some were criminals who enrolled to have their sentences commuted. Shelby lacked adequate state or federal funds to equip them or even provide rations.48

Governor Shelby had no state funds to purchase boats, and General James Taylor, quartermaster of the Kentucky militia, stepped forward. Taylor was one of the pioneers who founded Newport, and within twenty years after the war he would invest in banking, manufacturing, and other ventures and rise to become northern Kentucky's most wealthy and influential citizen. He had emigrated from Virginia, and, in 1803, his second cousin, Secretary of State James Madison, approved his proposal to move Fort Washington army post from Cincinnati to Newport with the new name of Newport Barracks. He donated five acres, and the War Department selected him as superintendent of construction for the fort. Early in the War of 1812, he served as General Hull's quartermaster in the ill-fated Detroit campaign. For the New Orleans expedition, he mortgaged some of his personal land holdings for six thousand dollars to purchase the boats that transported the militia to New Orleans. He was seventy-nine years old in November 1848 and near death when the presidential election occurred. Another one of his cousins, Zachary Taylor, was one of the nominees for president. The election judges came to his mansion and recorded his vote for his kinsman. “I have given the last shot for my country,” he said.49

The people of New Orleans, however, were grateful to the men, and their hearts went out to them. Citizens took up a collection of six thousand dollars, and the Louisiana legislature appropriated another six thousand dollars. With the money, civic leaders purchased cloth, and women volunteered to make cloaks, shirts, pants, and other garments. General John Thomas was in command of the Kentucky division, but he was unwell and had Adair take over. On the afternoon before the decisive battle of January 8, 1815, Jackson gave Adair a tour of the parapet his men had erected five miles south of the town on the east bank of the Mississippi River. He asked Adair what was lacking, and Adair replied that Jackson needed a reserve corps that could be moved into the front line to reinforce the men bearing the brunt of the British attack. Jackson agreed and asked Adair to deploy as many Kentuckians as were armed as that reserve. Some of the men had rifles, but Adair began asking around and soon learned that several hundred rifles were in the armory in New Orleans. He led a detachment into the city that night and obtained enough small arms to bring his strength of armed men up to about one thousand. At 4:00 A.M. the day of the battle, Adair moved his command forward to the center of the line, where they united with over three thousand Tennessee militiamen under General William Carroll. There was no more fateful place in the world to be that day than in the center of Jackson's line, where the British concentrated their assault.50

The British commander was the talented general Sir Edward Michael Pakenham, who had an army of eight to ten thousand disciplined veterans. Including Adair's Kentuckians, Jackson had over five thousand men behind the parapet, and Pakenham expected every one of them, as untrained, undisciplined militiamen, to run away at the first volley by his regulars. When the fog lifted at about 8:00 A.M. and the bright sunshine appeared, the Kentuckians looked over the breastwork, and there, 650 yards away and stretching for as far as one could see, stood the magnificent British army of fifty-three hundred beautifully dressed men. White belts crossing their scarlet uniforms gleamed in the sunshine, flags fluttered in the breeze, and drums were beating in unison. In the rear, men were holding fascines and ladders to breach the breastwork after the Americans started running.51

Both sides cheered, and the British began moving steadily forward. When they reached within five hundred yards, the American artillery began firing, and, when they came within one hundred yards, General Carroll yelled, “Fire! Fire!” Jackson shouted, “Stand to your guns, don't waste our ammunition—see that every shot tells.” Carroll's men were in four lines; the first line took careful aim and fired and stepped to the rear to reload, making way for the second line to step up and fire, and then the third line and the fourth line. This meant that their fire was almost continuous, and their accuracy was deadly. “Our men did not seem to apprehend any danger,” recalled one of the Kentuckians, “but would load and fire as fast as they could, talking, swearing, and joking all the time.” Historian Robert Remini wrote: “The Tennessee and Kentucky riflemen never seemed to miss a target, so skilled were they. With each shot a red coat collapsed to the ground.” Pakenham was hit in his bridle arm, and his horse was killed. He mounted another, and grapeshot struck his thigh and killed this horse. Then another shot struck him in the groin; he lost consciousness and was taken to an oak tree in the rear, where he died. After twenty-five minutes, the ground in front of Carroll's position was covered with the red uniforms of the dead and wounded. A Kentucky militiaman recorded that it looked like a sea of red. Among the three thousand who came within range of Jackson's fire, over two thousand were killed or wounded.52

Jackson ordered a cease-fire and walked the battle line congratulating his men and acknowledging their cheers. Then, hearing gunfire across the river, he realized that a British detachment was attacking his artillery battery on the opposite shore. He and Adair stood on the levee and watched through a field glass. They could not see clearly, but the flashes moved north, beyond the battery, and Jackson realized that his men on the west bank had been defeated. Since he was thirteen years old, he had dreamed of totally defeating a British army, and the repulse on the west bank denied him of that pleasure. At the moment, he did not know whom to blame, but historians agree that Jackson himself was at fault. Instead of accepting responsibility, however, he unjustly placed the entire blame for the American defeat on the west bank on a detachment of two hundred Kentucky militiamen.53

The brave Kentuckians Jackson blamed probably suffered through the most exhausting and physically challenging twenty-four hours of any of the American detachments in the battle that day. On the morning of January 7, the day before the battle, they numbered four hundred, and, since they were unarmed, they were ordered to shovel and work on the parapet. At nightfall, their commander, Colonel John Davis, received orders to march the detachment five miles to New Orleans, take the weapons in the armory, cross the river on ferries to the west bank, and march south to reinforce the small American force protecting the artillery on the west bank opposite the parapet. They started toward the city at 7:00 P.M., and, when they arrived, they discovered that Adair had already taken the rifles. Nevertheless, Davis somehow obtained two hundred rifles, and, leaving half the men in the city, he moved south with the two hundred men who were armed. When he arrived at the artillery battery, it was 4:00 A.M.; his men were exhausted from having gone without sleep and walking the last few miles on a road that was knee-deep in mud and water.54

Davis reported to Louisiana militia general David Morgan, whom Jackson had posted in an impossible position. Morgan had only 420 Louisiana militiamen and now, with Davis's force, 620; he was expected to protect the artillery against a force of British regulars landing in boats and marching north against him. Morgan made a bad situation even worse by dividing his men into three detachments in the hope that one of the detachments would be lucky enough to be at the point on the riverbank where the enemy landed to fire on them as they disembarked. But the British force of 440 men under Colonel William Thornton landed below Morgan's positions, first routing his small advance detachment of Louisianans, and then moving against Davis and the Kentuckians. Outnumbered, they had no choice but to withdraw to the main defensive line, and Morgan placed them on his right, where they were openly exposed to flanking attacks on both the right and the left. When Thornton saw Morgan's line, he identified the weak points on the right and left of Davis and focused his attack on those positions. The Kentuckians again had no choice but to retreat. Morgan withdrew as well, but he and Davis had given time for the gunners to spike all their cannon and throw them into the river. Thornton occupied the empty artillery battery, but it was a barren victory because his mission was to arrive hours before the battle on the east bank, seize the cannon, and turn them on Jackson's main line during the main battle.55

There was no glory for anyone on the west bank that day, but it was unfair to blame the Kentuckians. The next day in his report to Monroe, Jackson wrote incorrectly that Morgan would almost certainly have won the engagement if the Kentuckians had not “ingloriously fled, drawing after them, by their example, the remainder of the forces; and thus yielding to the enemy that most fortunate position.” Historians agree that Jackson left the west bank vulnerable by placing so few men there, and it is a fact that he refused to heed advice to send additional reinforcements. Jackson's anger and bias against the Kentucky militia was evident again in his report when he slighted the contribution of Adair and the Kentucky riflemen who fought in the center of his line on the east bank. He stated that the Kentucky division added “very little” to his strength because only “a small portion” of them were armed.56

Few people outside Kentucky paid any attention to Jackson's unjust evaluation of the role of Kentuckians in his great victory. A broadside on the streets of New York City proclaimed that “the bravery of the Kentuckians, the Tennesseans &c. will be handed down to the latest posterity.” For decades, theater audiences nationwide applauded the song The Hunters of Kentucky, and, in praising Adair's men on the east bank, the lyrics made no mention of the fight on the west bank. But Adair challenged Jackson's report, and correspondence between the two of them in 1815 and again in 1817 sold a great many newspapers in Kentucky. Editors who supported Henry Clay gave the controversy prominent coverage: not only did it represent conflict in Jackson's political camp with his friend and supporter Adair, but it also symbolized justice for Kentucky veterans. Everyone knew about Jackson's record of dueling, so, when Adair accused him of being “loud, noisy, and abusive” like a town bully, Adair himself appeared brave and heroic. Adair had the last word, and his final letter praised the Kentucky militia for volunteering, risking a long passage of a thousand miles, and serving faithfully and decisively without proper food, pay, or weapons. And what was their reward from Jackson, he asked? The answer was “reproach and abuse.”57

The controversy made Adair a popular hero in Kentucky and contributed to his election as governor in 1820. Jackson's disparagement and his stubborn refusal to retract it echoed through Kentucky politics and public celebrations until the Civil War. Whigs used it against Jackson in the presidential campaigns of 1824, 1828, and 1832. On August 3, 1830, Clay spoke in Cincinnati against Jackson's veto of the Maysville Road bill. He said it fell heavily on Kentucky and seemed unfair given the state's unparalleled support of the nation in battle, including the fight by Jackson's side in the glorious Battle of New Orleans. Until the Civil War, towns throughout the nation celebrated every January 8 with almost the same enthusiasm as the Fourth of July. However, in Kentucky January 8 reminded people of Jackson's insult. On the twenty-fifth anniversary of the battle, January 8, 1840, the General Assembly discussed honoring Jackson and the victory by firing one of the cannon captured at the Battle of the Thames. A state senator said that it would be an affront to Kentucky veterans to explode gunpowder to honor Jackson. The senators deliberated and finally agreed not to mention Jackson but to fire the salute in honor of “the brave American officers and soldiers” in the Battle of New Orleans.58

In the War of 1812, nonregular Kentucky soldiers demonstrated that they could fight as well as regulars. With the support of a small detachment of regular army soldiers, they won the strategic Battle of the Thames, which, with Perry's victory on Lake Erie, achieved American control of Upper Canada. Kentucky volunteers participated effectively in the main Battle of New Orleans, and, even though it was fought after the Treaty of Ghent, the victory on the battlefield confirmed that the treaty would not be renegotiated. Kentuckians were proud that Henry Clay was one of the five commissioners who negotiated the treaty. On the other hand, Kentucky's fighting men also demonstrated the truth of Theodore Roosevelt's objection that militia could be an undependable, brittle sword. The Hopkins Raid was lengthy and fatiguing, and many became sullen and deserted, contributing to the failure. At Dudley's Defeat, the men showed a lack of discipline by not withdrawing when the raid had succeeded, and the result was disastrous.

Publicity and public opinion emphasized the positive contributions, with the result that Kentucky emerged with more than its share of heroes, and romantic poems and songs mentioning Kentuckians such as George Croghan, William Whitley, Isaac Shelby, and Richard Johnson kept alive the legendary image of the Kentucky fighting man. In Kentucky, this meant that men of military age were expected to live up to the ideal and be prepared to shoulder their rifles and fight for their nation when summoned. An English traveler observed in the mid-nineteenth century that “Kentuckians have the character of being the best warriors of the United States,” and a member of the Louisville Legion preparing to leave for Mexico in 1846 assured his wife that, if there was a fight, he and his friends would demonstrate “Kentucky spunk.”59