9

Surgery, Medical Botany,

and Science

1800–1825

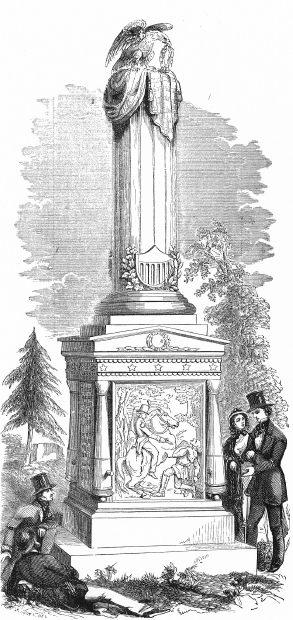

Rarely in history does an innovator make a discovery in a life-and-death situation that overturns the traditional wisdom of centuries; when it happens, it is even more exceptional when history gives that innovator clear and unchallenged credit for the breakthrough. Dr. Ephraim McDowell accomplished this, and Kentuckians honor him, along with Henry Clay, as one of the greatest heroes in their state's history. When Congress invited the states to donate two statues to National Statuary Hall in the U.S. Capitol, Kentucky selected as their subjects Clay and McDowell. McDowell's statue was unveiled on March 3, 1929; the New York Times identified him as an “eminent physician and surgeon.” Both statues were by New York sculptor Charles H. Niehaus, who donated his two clay models to Kentucky; they were bronzed and installed in the Kentucky capitol rotunda in November 1930.1

McDowell is recognized throughout the world as the father of abdominal surgery for performing the first ovariotomy in history in Danville, Kentucky, in 1809. He was born on November 11, 1771, in Augusta County (later Rockbridge County), Virginia; his parents brought him and his siblings to Kentucky when he was eleven years old. He attended school in Kentucky and returned to Virginia to study medicine under Alexander Humphreys of Staunton. After a few years, he went to Scotland to study anatomy and surgery at the University of Edinburgh, the leading medical school of the day. Many medical students at the time attended lectures for a year or two and left without an M.D. degree, and so it was with McDowell—he came home in 1795 and began practicing in Danville. In 1802, he advanced in society by marrying Sarah Hart Shelby, daughter of Kentucky's first governor, Isaac Shelby.2

Word spread that, when he operated, his patients nearly always recovered, and his fame reached central Tennessee, where seventeen-year-old future president James K. Polk was in excruciating pain with a bladder stone and recurring urinary infections. Polk came to Danville in 1812; McDowell operated, and Polk went home with the stone in his pocket. Fourteen years later, he thanked McDowell for changing him from a boy “with pallid cheek, oppressed and worn down with disease,” into “the man of today in full enjoyment of perfect health.” By 1828, McDowell had performed the same operation, a lithotomy, thirty-two times, and all the patients recovered, a remarkable accomplishment in the days before anesthesia and antisepsis.3

Frequently, physicians who were baffled by their cases would summon McDowell. About three years before the Polk surgery, in December 1809, two Green County doctors asked him for assistance with Mrs. Jane Crawford, who lived on a farm near Greensburg, sixty miles southwest of Danville. She and her husband, Thomas Crawford, had four children, and a fifth child had died in infancy. She was forty-five years old and thought she was past her fertility, but her doctors told her she was pregnant with twins. By the end of the tenth month, she was in terrible pain, but there were no labor and no birth. McDowell arrived and, after becoming acquainted with the family, asked Mr. Crawford for permission to examine his wife. He consented, and after the examination McDowell told them Jane was not pregnant but had a tumor on an ovary.4

Mrs. Crawford asked McDowell whether he could remove the tumor, and he answered that his professors in Scotland taught that women with ovarian tumors had no choice but to suffer in agony for about two years unless God performed a miracle and healed them. His professors said that the danger of infection from opening the abdomen was so great that death was inevitable. Anesthesia was over thirty years in the future, and, because surgery was so painful, the number one goal of most surgeons was speed; the rule was “more haste, less pain.” It was believed that a patient could not survive an operation that lasted more than three minutes—the length of an amputation. There was no knowledge of microorganisms and no asepsis or sterile operating environment until the late nineteenth century. Therefore, the surgery student was warned not to open the major cavities of the body and expose them to the atmosphere because the patient would die and the surgeon would lose his peace of mind.5

On the other hand, McDowell knew that female animals survived spaying, and he had seen male patients wounded in Indian fighting who survived abdominal wounds that remained open for several hours before surgery. “If you think you are prepared to die,” he told Mrs. Crawford, “I will take the lump from you if you will come to Danville.” He did not say the operation was a surgical procedure—he said it was an “experiment,” but she immediately agreed and later told her friends she was going to Danville for “the experiment.”6

The examination in the Crawford home was on December 13, 1809; about a week later, she made the journey to Danville on horseback, over two or three days, with the tumor resting on the saddle horn. On Christmas morning on a table in his home office, McDowell performed the operation, assisted by his nephew, Dr. James McDowell. Crawford's only diversion was reciting Psalms she had memorized. The surgery lasted twenty-five minutes. The tumor weighed twenty-two and a half pounds. Five days later, she made her bed, and twenty-five days after the surgery she went home and lived another thirty-eight years. After her husband died years later, she moved to Graysville, Indiana, to live with James Crawford, one of her sons who was a Presbyterian minister. She died at James's home on March 30, 1842, at the age of seventy-eight.7

McDowell performed the operation successfully on three additional patients and in 1817 published an article in the medical journal Eclectic Repertory, published in Philadelphia. Eventually, he conducted a total of eleven ovariotomies. He was a quiet man, reluctant to promote himself—he wrote the article only after years of urging by his friends, who emphasized that the knowledge thus conveyed would save many lives. When his article made the news, the London Medico-Chirurgical Review condemned him, and Philip Syng Physick, a prominent surgery professor at the University of Pennsylvania, denied that it was a breakthrough. However, the Medical Society of Philadelphia announced the surgery almost immediately as pathbreaking, as a positive breakthrough. Several years later, in 1825, the University of Maryland awarded McDowell an honorary degree. Active in the community, he was one of the founders of Centre College and served as one of the college's trustees for its first ten years.8

Ironically, McDowell died at the age of fifty-eight on June 25, 1830, and his symptoms closely matched those of appendicitis. If he truly had appendicitis, the appendectomy that became common by the twentieth century might have saved his life. He became more famous after his death, and, during the Civil War, a patent-medicine company used his name to endorse “cures” for impurities in the blood and for syphilis. The ads claimed, inaccurately, that McDowell was a member of the Royal College of Physicians of Ireland and that he had published articles in a prominent British medical journal. In 1879, the Kentucky State Medical Society dedicated a monument in his memory in Danville, and, in 1935, the Kentucky Medical Association unveiled a monument in McDowell Park in Danville to Jane Crawford. McDowell's home and apothecary shop have been restored and are open to the public. In 1959, the U.S. post office recognized the 150th anniversary of the famous surgery with a four-cent McDowell stamp, released in Danville.9

McDowell entered the profession with an apprenticeship with Alexander Humphreys of Staunton, Virginia, and most physicians in early Kentucky were educated in apprenticeships with practicing physicians. A few doctors were among the early settlers, and they taught their students traditional medical theory and practice, which dated back to ancient Greece and Rome. They usually fought measles (often referred to as “eruptive fever” and often quite dangerous), typhoid fever, and other “mal-arious” (literally “bad air”) diseases under the theory that the body was out of balance and health could be regained by restoring the balance through home remedies, diet, stimulating tonics, and especially depletive therapy such as bleeding and purging. Surgery was usually limited to the setting of fractures, the treatment of wounds and superficial growths, and amputations. Kentucky moved forward in medical education with the creation of the Medical Department at Transylvania University in 1799. Dr. Samuel Brown taught as professor of chemistry, anatomy, and surgery; Dr. Frederick Ridgely was professor of the practice of physic, materia medica, and midwifery. Nevertheless, few students were enrolled until the department was reorganized and enlarged in 1817; until then, most Kentucky physicians trained as apprentices. But, with the arrival of Horace Holley, things changed. From 1818 to 1827, under his able leadership, Transylvania University developed one of the finest medical departments in the country.10

The best medicine is prevention, and one Kentucky physician immediately recognized the value of vaccination for smallpox when he first read about it. English physician Edward Jenner's discovery that cultured cowpox virus would immunize against smallpox without infecting the person was published in 1799, but, nevertheless, physicians in Boston, New York, and Philadelphia were slow to vaccinate. In Lexington, Professor Samuel Brown showed no such hesitation—he began vaccinating; by 1802, he had immunized five hundred people. Brown was a Virginia native with an M.D. degree from Aberdeen University. After practicing and teaching at Transylvania for several years, in 1806 he moved to the Deep South, where he owned and managed plantations in Mississippi and then Alabama. He was supervising the farming on his plantation near Huntsville when President Horace Holley persuaded him to return to Transylvania as professor of the theory and practice of medicine in 1819. Well-known in his day among scientists, he was a member of the American Philosophical Society and a friend of Thomas Jefferson, who appointed him as an adviser on Indian culture during preparations for the Lewis and Clark expedition. He contributed to the Kentucky economy by analyzing cave nitre and announcing that it was valuable for manufacturing gunpowder. John Wesley Hunt and others profited by marketing large quantities of gunpowder during the War of 1812.11

A brave Kentucky surgeon, Dr. Walter Brashear, made medical history in 1806 in Bardstown. He operated on a local young man identified in the record only as “a mulatto lad” and slave. He was seventeen years old and was in great pain with a leg severely mangled in an accident. It was a complex fracture of the thigh bone with bruising and laceration of the entire limb. The only answer was amputation, but amputating at the hip was so complicated and difficult that it had never been done in America as far as Brashear or anyone knew. Later, when Civil War surgeons performed the operation on wounded soldiers, it had one of the highest mortality rates of any surgery. The young man was fortunate to have Brashear as his physician because he had the heart of an adventurer; he had the courage to innovate. Brashear studied at Transylvania University, earned his M.D. degree under Benjamin Rush in Philadelphia, and signed on as the surgeon of a clipper ship for a voyage to China. The surgery in Bardstown was without benefit of known precedent or protocols; Brashear amputated the leg at the hip, and the young man recovered and lived a long life. Actually, although Brashear apparently never knew it, Baron Dominique Jean Larrey, chief surgeon of Napoléon's army, and other surgeons in Napoléon's army had performed the amputation earlier. Today, Brashear is somewhat of a legend on the Internet, where he is credited with performing the first hip-joint amputation in world history.12

Another pathbreaking Kentucky surgeon in the days before anesthesia and antiseptics was Benjamin W. Dudley, who advanced aneurysmal surgery and pioneered in the treatment of traumatic epilepsy in America with trephination, according to medical historian Porter Mayo. Among Kentuckians, however, Dudley's greatest fame resulted from his phenomenal success in removing bladder stones, in lithotomies. Dudley performed the surgery 225 times to McDowell's modest 32, and, moreover, he achieved a phenomenally low mortality rate of only 1.3 percent. Dudley was born in Spott-sylvania County, Virginia, on April 12, 1785, and with his family moved to Bryan's Station, Kentucky, the next year. In 1797, the family moved to the Lexington area, where Dudley apprenticed to popular Transylvania University professor of medicine Frederick Ridgely.13

In 1804, Dudley enrolled in medical school at the University of Pennsylvania and graduated with an M.D. degree in 1806. He practiced in Lexington for four years and left for Europe in 1810 for further training. In Paris, he studied for three years under world-renowned surgeons, such as Dominique Jean Larrey. He studied in London for another year under English surgeon Sir Ashley Cooper and others and earned a diploma from the Royal College of Surgeons. When he returned to Lexington in 1816, he was one of the best-educated surgeons in America. In 1817, Transylvania University gave him special status as the leading faculty member in the Medical Department by employing him in two separate teaching positions: professor of anatomy and professor of surgery. His double salary and recognition caused a great deal of jealousy and may have contributed to the duel with his fellow faculty member William Richardson discussed in the next chapter. But Dudley believed that he fully deserved being set apart, and he never allowed envy to deter him. He affected the manners of upper-class Paris and dressed formally like a French aristocrat; he had dark curly hair, long tapered sideburns, a large nose, slightly upturned lips, and penetrating eyes that communicated a sense of superiority.14

Success made Dudley domineering; with his patients he was gruff and unbending. He told them that they could scream as loud as they wanted but that they were not to move. Once, a patient squirmed, and Dudley shouted:

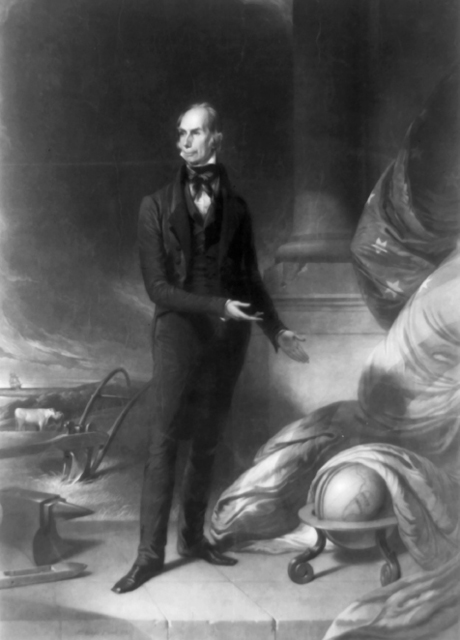

Henry Clay represented the hope of Kentuckians in global progress and freedom. John Neagle, engraved by John Sartain, Library of Congress.

Artists attempted to portray one of the features of Henry Clay's great speeches—he made sweeping, dramatic gestures with his long arms and pointed emphatically with his right index finger. James Wise, engraved by John Sartain, Library of Congress.

Henry Clay pleaded for preservation of the Union in the U.S. Senate in 1850. P. F. Rothermel, engraved by Robert Whitechurch, Library of Congress.

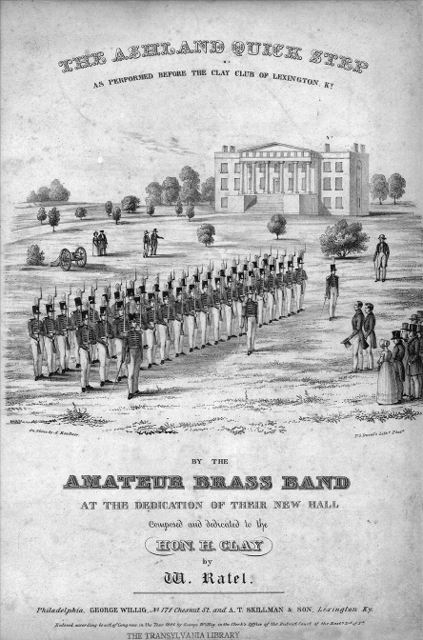

Henry Clay reviewing a militia company on the campus of Transylvania University. Sheet Music, The Ashland Quick Step, Henry Clay Collection, Transylvania University Library.

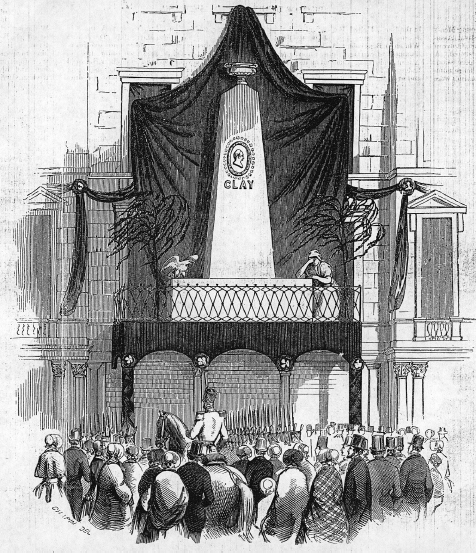

Henry Clay was the most popular man in America when he died. For his funeral procession in New York City, Stewart's department store and other businesses were decorated in mourning. Gleason's Pictorial Drawing Room Companion, August 14, 1852.

Richard M. Johnson became famous as “Old Tecumseh” for reportedly killing Chief Tecumseh in the Battle of the Thames. Ballou's Pictorial Drawing Room Companion, June 10, 1854, courtesy Martin F. Schmidt, ed., Kentucky Illustrated: The First Hundred Years (1992).

This popular song idolized the Kentucky militia in the Battle of New Orleans. The Hunters of Kentucky, Filson Historical Society.

Large flocks of Carolina parakeets, now extinct, flew to Big Bone Lick to drink the brine. The numbers in the illustration identify whether a bird is male (1), female (2), or young (3). Carolina Parakeet, in John James Audubon, The Birds of America, with a foreword and captions by William Vogt (1937; reprint, New York: Macmillan, 1946), pl. 26.

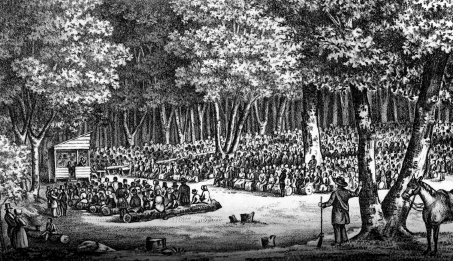

Camp meeting during the Great Revival, 1801. Kentucky Historical Society.

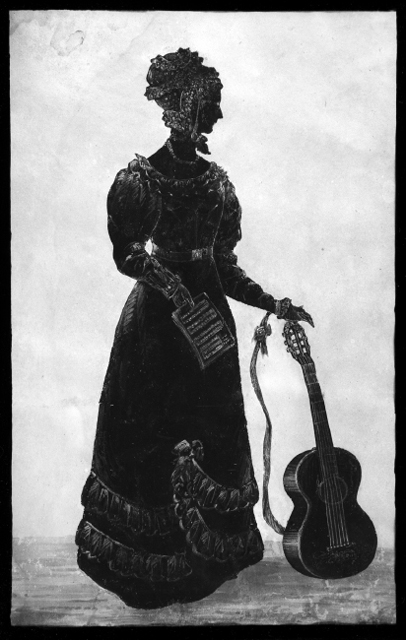

Mary Austin Holley, wife of Transylvania University president Horace Holley and a talented poet, song lyrics writer, and guitarist, contributed to early Kentucky's cultural renaissance. Mary Austin Holley silhouette, photograph of the original, Horace Holley Collection, Transylvania University Library.

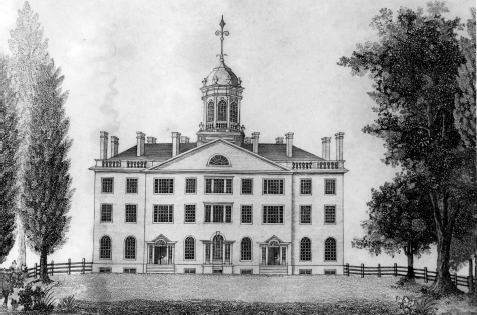

(Above) Principal Building, Transylvania University, 1818. Transylvania University Archives Photographs. (Below) Architect Gideon Shryock designed Transylvania University's Morrison Hall, dedicated in 1833. Old Morrison, J. Winston Coleman Jr. Photographic Collection, Transylvania University Library.

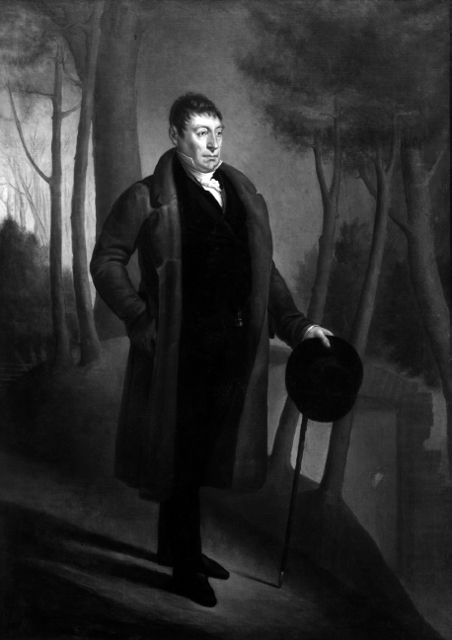

General Lafayette was impressed with Kentucky's patriotic spirit and progress in manufacturing, education, and culture. The Kentucky General Assembly commissioned Kentucky artist Matthew Jouett to paint his portrait. Matthew Jouett after Ary Scheffer, Kentucky Historical Society Library.

(Above) The outstanding sports painter Edward Troye painted the racehorse Lexington, foaled in the Bluegrass in 1850. Edward Troye, Lexington, J. Winston Coleman Jr. Photographic Collection, Transylvania University Library. (Below) Battle of Buena Vista. Library of Congress.

(Above) Battle of Buena Vista. Currier and Ives lithograph, 1847, Library of Congress. (Below) Gallant Charge of the Kentuckians at the Battle of Buena Vista. Currier and Ives lithograph, ca. 1847, Library of Congress.

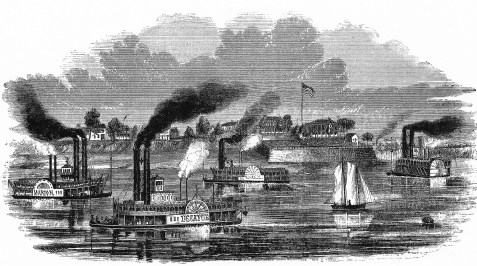

(Above) Kentuckians celebrated advances in the speed of steamboats, and the Louisville area manufactured some of the fastest, most luxurious “floating palaces.” “Rounding a Bend” on the Mississippi: The Parting Salute. Currier and Ives, ca. 1866, Library of Congress. (Below) Before 1850, Louisville was the Ohio River steamboat transshipment center. In the 1850s, Cincinnati surpassed Louisville in shipping, and Newport and Covington participated in the area's economic growth. The flag waves over Newport Barracks. Martin F. Schmidt, ed., Kentucky Illustrated: The First Hundred Years (1992).

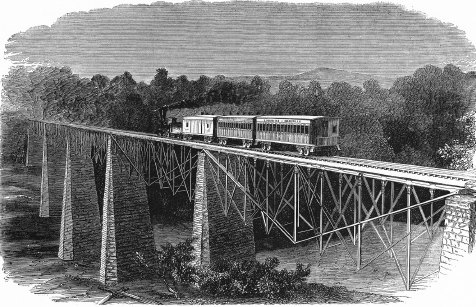

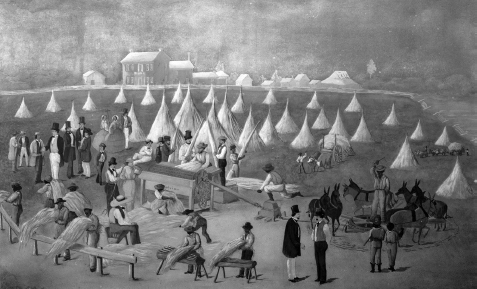

(Above) The Louisville and Nashville Railroad reduced travel time to Nashville to less than ten hours. This engraving portrays a train on the Green River bridge. Harper's Weekly, February 25, 1860, in Martin F. Schmidt, ed., Kentucky Illustrated: The First Hundred Years (1992). (Below) The process of harvesting hemp was labor intensive, and many Kentucky slaves were involved throughout the Bluegrass region. Kentucky Historical Society.

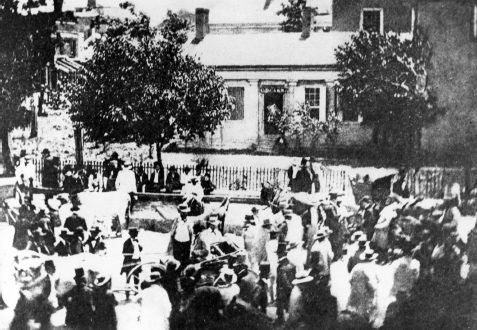

Slave auction on Cheapside, Lexington. J. Winston Coleman Jr. Photographic Collection, Transylvania University Library.

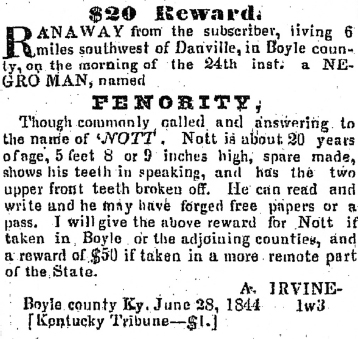

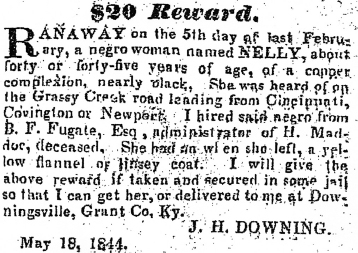

(Above) While Kentucky law never prohibited the education of slaves, many masters shunned the practice to prevent the forging of free papers. Licking Valley Register, August 10, 1844. (Below) Runaway ads often included descriptions of clothing to help identify escaped slaves. Licking Valley Register, August 10, 1844.

Lexington Main Street, 1859. J. Winston Coleman Jr. Photographic Collection, Transylvania University Library.

Confederate President Jefferson Davis led the war of proclamations with the goal of persuading Kentuckians to secede from the Union. Frank Leslie's Illustrated, March 9, 1861, Library of Congress.

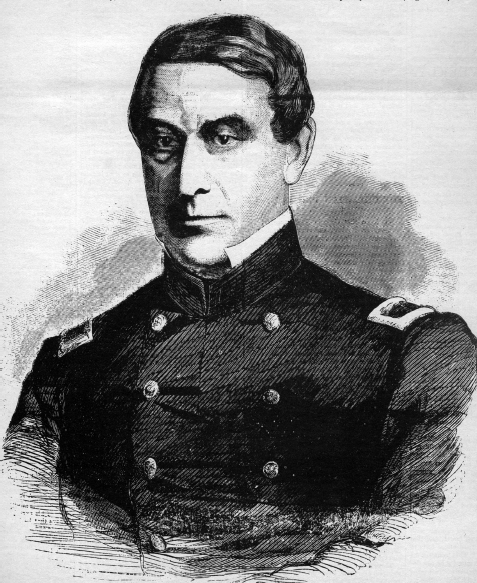

Robert Anderson, “the Hero of Fort Sumter,” was the Union's first Civil War hero. Harper's Weekly, January 12, 1861, courtesy Eva G. Farris Special Collections, W. Frank Steely Library, Northern Kentucky University.

Confederate general Albert Sidney Johnston. Library of Congress.

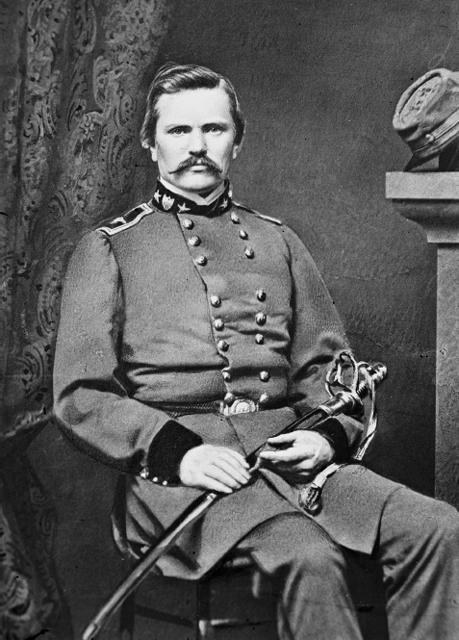

Confederate general Simon Bolivar Buckner. Library of Congress.

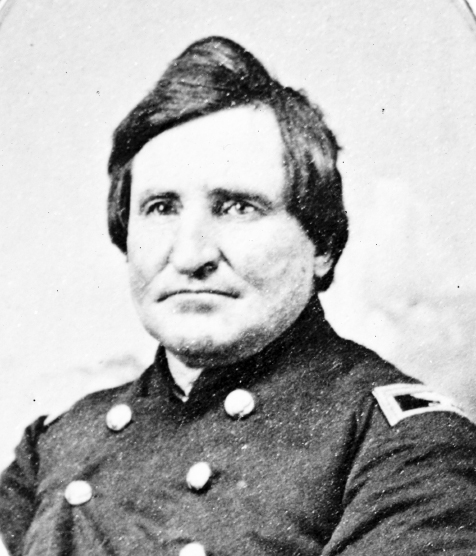

Union colonel Frank Wolford. Library of Congress.

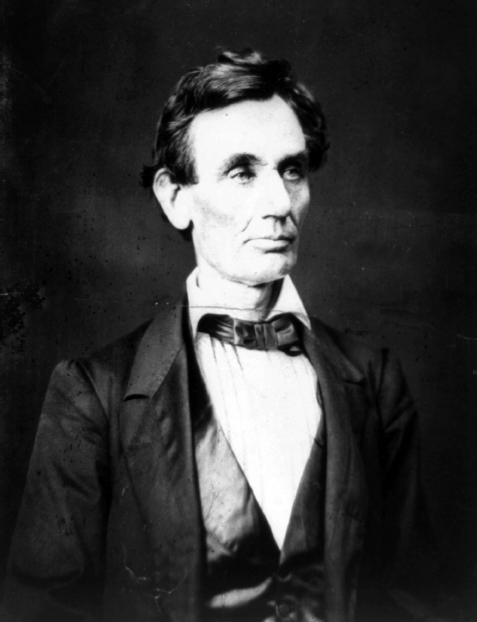

Abraham Lincoln began freeing Kentucky's slaves as quickly as possible given the necessity of keeping the vital state in the Union. He dreamed of the day when Kentuckians would be united in freedom and equality. Lincoln as presidential candidate, Library of Congress.

“Be still, Sir, or I'll send your soul to Hell in half a second.”15 Continually striving for success, Dudley used every weapon in his armamentarium. To take advantage of the prayers of the friends of his patients, he scheduled his most difficult operations during Sunday morning worship. “Young gentlemen,” he told his student assistants, “be ready to move to a certain house by the ringing of the last church bells.” Like McDowell, he insisted on a clean operating environment. Somehow he had come to the conclusion that filth contained “the seeds of disease” and that unboiled water carried poisons. He had his instruments washed in boiled water, and each patient was thoroughly bathed in boiled water. In 1935, an article in the journal Annals of Medical History declared that he used “the essentials of modern surgical practice half a century before the principles underlying them had been revealed.”16

The removal of bladder stones dated back to ancient times, but few surgeons other than McDowell and Dudley had the courage to perform the operation. Dudley's first lithotomy to attract the attention of the Kentucky Gazette was his November 26, 1817, operation in Lexington on an adult male. The stone weighed nearly two ounces and was one and three-quarters of an inch long. He had performed the surgery one time previously, at some undetermined earlier date, on a small boy in Paris, Kentucky. McDowell's success in Danville was being duplicated in the Bluegrass, and the Kentucky Gazette trumpeted: “Our Medical College, Kentucky, the western country at large may well be proud of a professional man of the skill and talent of Dr. Dudley.” Dudley had an amphitheater constructed at his home, and there he taught his classes. McDowell's mantle fell on him when McDowell died in 1830, and Dudley's students admired him from then to his retirement in 1850 as the most successful surgeon in Kentucky. At one point he operated on a blind man who was twenty-one years old and had been blind from birth. He briefed his class on the surgery, and, when it was time to remove the bandages, he brought the patient to class. The young man had confidence that he would be healed and said that the first sight he wanted to see was the face of his surgeon. The bandages were taken away, and he looked at Dudley, looked around the room, and with a thrilling “cry of delight” shouted that he could see.17

The forward-looking vision of Virginians and Kentuckians who created Transylvania University, the first university west of the Appalachian Mountains, shared the same positive view of national development as Henry Clay's as expressed in his American System. Clay's vision of the future greatness of the nation influenced President John Quincy Adams when Adams presented his first State of the Union address on December 6, 1825. Clay was Adams's secretary of state and one of his advisers, but the speech was the president's. Adams declared that “the spirit of improvement is abroad upon the earth” and that the federal government should encourage “geographical and astronomical science,” agriculture, commerce, manufactures, art, and literature. “Liberty is power,” he said, and the federal government should sponsor exploration of the West Coast, adoption of a uniform standard of weights and measures, a national university, an astronomical observatory, and extensive construction of roads, canals, bridges, and other internal improvements. With the idea of a national university, he out-Clayed Henry Clay because Clay did not believe that federal spending on higher education was supported by the same constitutional principles as spending on a national bank or internal improvements. Adams's Jacksonian Democratic opponents ridiculed the speech as the dangerous idea of a schoolboy, a mockery of the limits of the Constitution on the power of Congress. Andrew Jackson said he shuddered at this despotism that violated “the voice of the people.” Today, most Americans agree that Adams was right and Jackson wrong; the nation has gone far beyond nearly all his proposals in one way or another.18

When Adams spoke of the spirit of improvement and interest in science, he was attempting to further the awakening of interest developing in medicine, mathematics, and science in American colleges. It was a continuation of the nationalism and buoyant spirit abroad in the land from the close of the War of 1812. Kentuckians participated in the enthusiasm and, like Adams and Clay, moved far ahead of their time in their vision. Many of the Kentucky leaders, including several Kentucky governors, were almost a century ahead of their time when they attempted to make Transylvania University in Lexington a great nonsectarian state university supported with funding from the Kentucky state government. The trustees of the institution conducted a national search and succeeded in recruiting Horace Holley, a great, ideal president who shared their vision. Holley agreed with John Quincy Adams that there should be a national university, and he wanted each state to have one major state institution. With Holley as president, Transylvania achieved greatness and national ranking for a few years, but the idea of a state-supported university met some of the same kind of opposition that Adams and Clay faced on the national level; seventeen days after Adams's speech, Holley resigned, signaling the eclipse of Kentucky's vision.19

The dream dated back to 1780, when Kentucky was a county of Virginia and the Virginia legislature chartered Transylvania Seminary as a state-supported college with a land grant of eight thousand acres. It opened in Lexington in 1797, and on January 1, 1799, the Kentucky legislature approved the union of Transylvania Seminary with the Presbyterian Kentucky Academy to create the new institution of Transylvania University. However, from 1804 to 1815, Calvinistic Presbyterian leaders dominated the board of trustees, and the school was essentially a Presbyterian seminary. Then, amid the euphoria of the Battle of New Orleans and what seemed to be victory in the War of 1812, Henry Clay and other liberals opposed to Presbyterian Calvinism determined to seize control of the school, recruit a great president, and develop outstanding law and medical departments. They adopted “the ideal of a great central state university, open to all religious denominations, and conducted on liberal principles.” And, remarkably, the Democratic Republican governor Gabriel Slaughter and the controlling Democratic Republican Party in the General Assembly fully supported Holley and his vision.20

Liberals recommended Holley, and the Presbyterian-dominated board of trustees elected him on November 11, 1815. Then, the board members learned that Holley was pastor of a Unitarian church, and they rescinded the election. The Kentucky House of Representatives enacted a bill to reorganize the board in order to overthrow Presbyterian dominance, and, even though it failed in the Senate, the point was made. The board reconsidered, and on November 15, 1817, a bare majority voted to elect Holley. Obviously, if Holley were to succeed, he needed a new board, and, in December 1817, the legislature gave him a new board—it dismissed the old trustees and elected thirteen new ones, including Henry Clay, all of whom favored Holley.21

Horace Holley was an outstanding leader—people who knew him well realized that only once in several generations would you meet a man like him. He had studied at Yale, he was a member of the board of overseers at Harvard, and he could have been president of any university in the East or could have had almost any executive position. He was born in Salisbury, Connecticut, and, when he was a student at Yale, he adopted Calvinism. Some Kentuckians thought that he was still a Calvinist, but he had become a Unitarian and was pastor of the Unitarian South End Church in Boston. He was an excellent administrator and a brilliant conversationalist who could talk with anyone; when he listened, one-on-one, he leaned forward and with his expressive dark brown eyes looked a person straight in the eye so that the individual knew Holley was paying attention and that he cared about a person as an individual. His high forehead was balding, and his nose was long, but his manners were elegant, and there were unusual strength and charisma in his presence.22

Boston had several eloquent speakers but no better orator than Holley. He moved gracefully, stirred the audience with his silver-toned voice, and lit up the room wherever he appeared. But here was no Aaron Burr-type self-promoter; his strength of character ran deep, and there is no better evidence of this than his intimate friendship with John Wesley Hunt and his family. Hunt gave no quarter to hypocrisy or superficiality—he was a righteous pillar in Christ Church Episcopal—and he was one of Holley's closest friends in Lexington. The two families spent many evenings in each other's homes. After the dream of legislative support died and Holley was under attack, he sent Hunt a letter thanking him for his support. “With your friendship for me I am entirely satisfied, and place unreserved confidence in the sincerity and simplicity of your declarations of respect and good will,” he wrote.23

Holley knew that there was opposition to his Unitarianism, and, before he accepted the presidency of Transylvania, he came to Kentucky to consider how much support there was for him and for a state university. He wanted to evaluate support among the trustees, clergy, and laymen. He was aware that the previous board rescinded his first election, and he received a warning from Presbyterian attorney James Fishback of Lexington that some people opposed his liberal theology. Holley was warmly received, however, by Henry Clay and other board members, Governor Slaughter, and other prominent citizens, and he was given many parties and dinners. He accepted invitations to speak in Episcopal, Baptist, and Methodist churches, and they responded warmly. Governor Slaughter was Baptist, and he and Baptist leaders promised to enroll their sons in the university and encourage their state legislators to approve appropriations for the school. Most Presbyterian clergy, however, regarded him as unorthodox, and they did not invite him to speak in their churches. On the other hand, the elders of one of the Presbyterian churches in Lexington invited him to speak, and he was well received. Many Presbyterians from other churches in the area attended and seemed to approve of him.24

Holley was surprised to find Lexington more beautiful than he had expected, “more comfortable and genteel.” He wrote a letter of acceptance, mentioning that he appreciated the wide popular support of his appointment and that he had a great expectation that the legislature and the community would sustain the university. He mentioned that Lexington was the Athens of the West and that therefore Kentucky as the Attica of the West was in an ideal position to establish a state university that would lead the Mississippi Valley. Before returning to Boston, he wrote his wife that he had accepted the position. “For the sole purpose of doing good,” he wrote, “I had rather be at the head of this institution than at the head of an Eastern college. The field is wider, the harvest more abundant, and the grain of a most excellent quality…. This whole Western country is to feed my seminary, which will send out lawyers, physicians, clergymen, statesmen, poets, orators, and savants, who will make the nation feel them.”25

One of Holley's priorities was to further the study of science. At his induction, he was given the key to the university, a Bible, and, according to a report in the Kentucky Gazette, “a volume of science, as an indication that instruction in knowledge and literature was his peculiar duty as head of an institution of learning.” Transylvania had the reputation of being the first university in the West, but, before he arrived, it was a small institution with less than eighty students and an incomplete faculty. From 1799 to 1818, it granted only twenty-two degrees. Holley realized that the key to a great state university was its faculty, and he began by strengthening the faculty of the Academic Department, the core of the university, the home of the liberal arts and the sciences. He volunteered to teach mental and moral philosophy and moved Robert Bishop from that position to teach natural science. Bishop later became an effective president of Miami University in Ohio. Holley's interest in strengthening the science faculty was demonstrated in his attempt to recruit Benjamin Silliman, the famous Yale chemistry professor. Silliman declined, but Holley was successful in employing Constantine Rafinesque, one of the greatest natural science teachers of the day.26

Holley's greatest achievement in science was strengthening the Medical Department, but the single act that had the greatest long-term scientific impact was his appointment of Constantine Samuel Rafinesque as the first professor of natural history in the Academic Department in 1819. Indeed, the final evaluation of Rafinesque's contribution in identifying Kentucky plants with medicinal value remains to be made by future generations. Many of the plants he identified are used today in healing drugs, but others remain to be explored. Not only that, Rafinesque was one of the best, most innovative science teachers in his day and one of the most colorful and eccentric professors in Kentucky history.27

His parents named him Constantine for Constantinople, the city of his birth. His father was a French merchant, and his mother was born in Germany and grew up in Greece. Soon after Constantine was born, the family moved to Italy, and there he mostly educated himself by reading in every branch of natural science. He lacked a tutor in science, and this left him with a severe gap in his education—no one taught him the critical method of thinking, and throughout his career he lacked discipline in scholarship; he was sloppy and careless, and his credulity destroyed the respect that fellow contemporary scientists might have had for him. As a young man, he came with his brother to Philadelphia from 1802 to 1805 and then lived in Sicily for ten years, where he married and had two children, made and sold medicine, and studied natural science on his own. In 1815, he left his wife and children in Sicily and emigrated to the United States. His wife, Josephine, heard that he was drowned in a shipwreck and quickly married the Italian comedian Giovanni Pizzalour. Rafinesque felt betrayed and never reconciled or reunited with Josephine.28

Rafinesque's great dream in life was to teach natural science in an American university, and Holley fulfilled it for him. But Rafinesque's passion for research and his scattered, unfocused approach to life resulted in the position not being permanent. That was still in the future when he moved to Lexington and started teaching, however. His students said that he was extremely well-read—he knew his subject and taught it well. He organized field trips and provided active-learning training in the collection and classification of flora and fauna. One of the first science teachers to bring living specimens to class, he displayed hundreds of plants, insects, and fish, and the room was so full of objects one scarcely knew where to look. In his fascinating lectures on ants, he said that ant colonies had generals and privates, and lawyers, and, after great battles, doctors and nurses to care for the wounded. “I would now give any reasonable sum to hear him repeat one of his lectures,” one of his students recalled later.29

Holley encouraged professors in the Academic Department to open their classes to people not enrolled as full-time students; Rafinesque was far ahead of his time in welcoming women into his classes and treating them with respect as intellectual equals. For fees, Lexington women took advantage of the opportunity, and his first course on natural history in the fall of 1819 had twenty-eight students, sixteen of them women. Medical students signed up as well to learn how to treat their patients with medical botany. Off the curriculum, Rafinesque taught courses in Spanish, French, and Italian and medical botany to the public. The learning was far advanced and most valuable, but the great bonus was watching Rafinesque and feeling his tremendous enthusiasm for his subject. He was one of the oddest-looking men Lexington had seen—he was short and stout, with delicate hands and small feet, and his huge balding head and large, intense black eyes seemed too large for his body. There was agreement that his appearance was “singular” (Audubon's word), meaning that his clothes never seemed to fit and he dressed in a nankeen waistcoat and wide Dutch pantaloons. His prominent French accent was delightful, and, as a pathbreaking scholar who published prolifically, he would get totally absorbed lecturing, and the tail of his white shirt would escape from his pants.30

His love for science and scientific research came out in his lectures and his daily conversation. He wrote that his most satisfying moments in life were his solitary field trips in the Kentucky wilderness searching for new plants. “I never was happier,” he wrote, “than when alone in the woods with the blossoms” or resting on the bank of a quiet stream.31 In 1821, Rafinesque conducted a research trip to Big Bone Lick in Boone County. This was a highlight for him as a scientist, and he wrote an article, “Visit to Big-Bone Lick,” reporting his visit in the Monthly Journal of Geology and Natural Science. Big Bone attracted visitors for several reasons. It was one of many mineral-spring resorts in Kentucky. These offered large hotels and bathhouses, and with the popularity of hydropathy—the art of healing from drinking or bathing in mineral water—one could not only enjoy the music and lectures but also justify taking off from work to “take the cure” for backache or some other lingering ailment. In 1803, a stagecoach line opened from Lexington to one of Kentucky's most popular spas, Olympian Springs in Bath County. Big Bone Lick had the special attraction of connecting to Indian folklore, paleontology, Lewis and Clark, and the debate on whether the European environment was superior to that of America. Most Kentuckians admired President Thomas Jefferson, and, when he opened the Mississippi River permanently by purchasing the Louisiana Territory, they gathered in grand public celebrations. Then, when Jefferson involved Kentuckians in the Corps of Discovery for the Lewis and Clark expedition, people followed the project and its relationship to Big Bone Lick with interest.32

Big Bone Lick was in the bend of the Ohio River in northern Kentucky, and visitors marveled at how accessible it was, only a few miles of easy walking from the Ohio River on a well-beaten path made through the forest by buffalo herds. On the frontier, travelers, scouts, and surveyors were relieved when they were able to walk on such paths; they called them buffalo roads, and there were four leading to the lick, one from each direction. Eyewitnesses reported that these buffalo traces were unusually distinct and wide enough for two wagons to meet without stopping, with soil as packed as a highway.33

Before the European hunters and settlers arrived, Shawnee and other Native American tribes came to Big Bone Lick to kill game, make salt, and paint designs on the trees. Game was so plentiful that even the most lazy, inefficient hunter could easily acquire more meat than he could take away. Large herds of buffalo, deer, elk, and other animals from distant parts swam the Ohio and Licking rivers and other streams, converging on the salt spring to drink the brine that apparently was nearly perfect for their taste and physiological needs. When they came close enough to smell the spring, they stepped up their pace, ran to the brine, and drank ravenously. Modern naturalists have identified twenty-two species of animal fossils in the lick. The hunting was so productive that Native Americans passed down a legend that the Great Spirit gave a special blessing to the humans and the deer and other small game at Big Bone.34

Big Bone Creek flowed through the twenty-acre clearing, and around the sulfurous-brine spring was a large, muddy marsh of about three-quarters of an acre. Surrounding it when the Europeans first came were hundreds of large bones whitening in the sun—tusks ten feet long, teeth called grinders weighing from four to twenty pounds, huge thigh bones, and vertebrae as large as footstools. Observers were astounded at the number and size of the bones. Today, historians are amazed at how many hundreds of bones were taken away and either lost in shipment or distributed throughout the United States, France, and England.35

In 1766, during his second visit to Big Bone, Indian trader George Croghan collected several hundred pounds of bones and sent a box of grinders and tusks to his friend Benjamin Franklin in London. He estimated that, when he left, there were still thirty skeletons of the great, unidentified animal at the lick. General William Henry Harrison collected thirteen hogsheads of bones in 1795, which were lost when the flatboat transporting them capsized west of Pittsburgh. After the Civil War, Nathaniel Southgate Shaler, a Kentuckian from Newport and recently appointed professor of paleontology at Harvard University, took away a wagonload. In 1936, reflecting on all the bones taken away, Kentucky state geologist Willard Rouse Jillson declared: “Such a profusion of bones! Such a multiplicity of individuals! Such a charnal [sic] house in nature!”36

Native Americans had never seen such a large animal, but tradition among the Shawnee and Delaware tribes claimed that the bones were from huge animals that had gathered around the salt lick to prey on the herds of deer and other game that came to drink. Legend had it that they would attack with one mighty leap and crush and devour the bodies of their prey, chewing with their giant teeth crowned with knobby surfaces. There was great fear that these giant animals would attack humans and apprehension that they would consume the game needed by humans for food. The Great Spirit intervened and killed all the giant animals with lightning bolts, except one big bull that escaped across the Ohio River and retreated into the wilderness beyond the Great Lakes.37

One of the travelers attracted to Big Bone Lick in 1810 was American ornithologist Alexander Wilson. In his classic American Ornithology, first published in seven volumes (1808-1813), he reported that he was not disappointed. He saw large flocks of pigeons and Carolina parakeets landing on the edge of the pond to drink the brine. Today, the Carolina parakeet is extinct, and it is regrettable because in the wild the birds were a natural wonder with bright yellow, green, and orange feathers. “They came screaming through the woods in the morning, about an hour after sunrise, to drink the salt water, of which they, as well as the pigeons, are remarkably fond,” Wilson wrote. They drank their fill and flew together into the sun, landing nearby on a tall tree. They filled every twig of the tree, and, for Wilson, the sun shining on their colorful plumage was “a very beautiful and splendid” sight.38

It took about an hour to walk from the Ohio River to Big Bone; when the traveler arrived, the forest opened, and he stood on high ground surrounding the twenty-acre clearing and saw the tall trees surrounding the clearing and the other three buffalo roads. He stepped down into the valley and walked through the bones to the edge of the marsh. Around the spring he might see open pits left by previous visitors who dug into the ground for bones. Five or six feet below the surface he might see bones protruding from the walls of an excavation, washed free by the rain.39

The unusual quantity of bones at Big Bone Lick may have resulted from the relatively lower salt content in the water. This made it less desirable for saltmaking but attractive to the animals and birds. Settlers boiled salt at the lick until about 1812, but salt manufacture ended after more productive licks were located. One had to evaporate five or six hundred gallons of brine to produce one bushel of salt, and other licks were several times more productive. Visitors approaching the spring noticed the strong smell of sulfur because the mineral water contained sulfur as well as salt. Settlers called it sulphur-saline spring water, and, after Kentucky was settled, this attracted people with medical problems, who came to drink and bathe in the water for healing through its mild medicinal quality. John Filson noted that one person with itch was cured after only one bath. Therefore, not long after saltmaking ended, a health spa opened at Big Bone Lick. Guests came for a week or two and lodged in the Clay House, a hotel named in honor of Henry Clay, located west of the spring. They lounged on the hotel's spacious veranda overlooking the valley and the row of bathhouses to the northeast. Near the hotel was a grove of tall oak and elm trees, and in the shade of their branches there was an open pavilion where at night guests danced and listened to music.40

The site was also famous as the place where Mary Ingles escaped from her Shawnee Indian captors. People in that generation were intrigued with accounts of settlers captured by the natives. This was one of the aspects of Daniel Boone's experience that made him a romantic frontier hero—he was captured by the Shawnee and, before his escape five months later, was adopted by Chief Black Fish and given the name Big Turtle. Mary Ingles was extremely well-known for having been captured in 1755 near present-day Blacksburg, Virginia, and taken to the Shawnee villages on the Scioto River in Ohio. After about two months, members of the tribe took her with them to Big Bone to make salt, and she and another woman captive escaped and walked along the banks of the Ohio and Kanawha rivers back to Mary's home. Kentucky Route 8 marks her escape and is named Mary Ingles Highway in her honor.41

However, the event that put Big Bone Lick on the map and turned all eyes on northern Kentucky was John Filson's book published in 1784 in Wilmington, Delaware. Filson was a native of Pennsylvania who had taught school and invested in land in Kentucky. He sought to encourage settlement to capitalize on his investment. Few books have been published at such an opportune moment; the great surge in immigration to Kentucky was just beginning that year and would continue for the next two decades. Kentucky had 73,077 residents by 1790, 220,995 by 1800, and 406,509 by 1810. They came mostly from Virginia, North Carolina, and Pennsylvania, and many had a copy of Filson's book and a copy of his map, initially published separately in the same year in Philadelphia. Filson wrote in the preface that the book was a complete guide to travelers bound for Kentucky.42

Filson's map—the first published that featured Kentucky—shows Big Bone Creek and at the salt springs has the notation “the large Bones are found here.” In the book, under “Curiosities,” Filson discussed the bones and how they were causing excitement among naturalists and laymen alike: “Specimens of them have been sent both to France and England, where they have been examined with the greatest diligence.” The bones were examined by naturalists such as Dr. William Hunter, prominent anatomist and physician for Queen Charlotte. Hunter had studied Big Bone Lick specimens in the royal collection in the Tower of London and determined that the giant animal was an unidentified quadruped, carnivorous, and probably extinct. Filson theorized that Native American tribes, “in perpetual alarm,” united and fortunately killed them all, for “how formidable an enemy to the human species, an animal as large as the elephant, the tyrant of the forests, perhaps the devourer of man!”43

Filson's report on Big Bone Lick struck a chord with readers because the big bones were the center of attention in the great naturalist question of the day, an emotional debate that involved patriotism and pride in the new nation. Filson was well read and was familiar with the writings of the distinguished French naturalist George Louis Leclerc de Buffon. Filson respected Buffon, characterizing him as an “ingenious” student of world climates. But Filson realized that, in America, Buffon was popularly known for publishing, before the American Revolution, the theory of American degeneracy, an idea that had strong support among European scientists. Buffon's theory asserted that New World soil was inferior and the climate too wet and humid for the growth of strong life forms, including humans. He said that Native Americans were weak and cowardly and that the only forms of life larger in America than in Europe were frogs, reptiles, and insects. When Filson's book appeared, Americans were determined to defend the United States by refuting and ridiculing Buffon's thesis. A few years later, Alexander Hamilton argued in one of the Federalist articles that one reason for ratifying the Constitution was to create a national government strong enough to create a navy; this would prove incorrect Buffon's arrogant claim that the air was so inferior in the New World that, when European dogs arrived, they stopped barking.44

The most obvious “proof of Buffon's ridiculous thesis seemed to be that America had no elephants or any other animals as large. Filson wrote of the bones from Big Bone Lick: “The bones themselves bear a great resemblance to those of the elephant. There is no other terrestrial animal now known large enough to produce them.” By comparing the unknown animal—called at the time the American incognitum from Latin for unknown—to an elephant, Filson may have been refuting Buffon. But elephants have smooth teeth, whereas the American animal's grinders with knobby crowns might mean that it ate flesh. Filson pointed out that Dr. Hunter had concluded that the animal's grinders indicated that the American incognitum was carnivorous. This made the huge animal more powerful and ferocious than an elephant; the American animal was, in Filson's words, “that prince of quadrupeds.”45

Thomas Jefferson, the leading American naturalist, realized that Buffon's theory was both wrong and biased, but he generally respected Buffon's work and determined to refute his ignorance with dramatic, scientific facts. When someone gave him a giant grinder from Big Bone Lick before the American Revolution, he recognized it as proof that the American environment had supported an animal as large as an elephant; since he had not yet accepted the idea of extinction, he thought that the creature might still be alive in the unexplored land beyond the frontier. Jefferson knew that a few big bones had been discovered along the Hudson River in New York, but he was more excited by the many big bones at Big Bone Lick.46

The year after Filson's book appeared, Jefferson rebutted Buffon in his Notes on the State of Virginia, first published in France in 1785. Referring chiefly to bones discovered at Big Bone Lick, he delighted in declaring: “The skeleton of the mammoth (for so the incognitum has been called) bespeaks an animal of six times the cubic volume of the elephant. The grinders are five times as large.” Dinosaurs had not been discovered yet, and he wrote accurately according to knowledge of the time that the American incognitum was “the largest of all terrestrial beings.”47

Jefferson's book was the deathblow to the theory of American degeneracy, but the mystery of the American incognitum remained. What was it? Did it still live? Did its grinders mean that it ate animals and humans? What would its entire skeleton look like? Jefferson wanted a collection of bones from Big Bone Lick to study these questions. The day before he sent his manuscript to the publisher, he asked Daniel Boone to deliver his December 19, 1781, letter to George Rogers Clark, commander of Fort Nelson at the Falls of the Ohio, requesting Clark to visit the salt lick, collect some of the teeth, and send them to him. Clark was unable to follow through, and the next opportunity came when Jefferson was president of the United States and sponsoring the Lewis and Clark expedition. By then, public interest in the American incognitum was intense. American poets and journalists fanned the flames by publishing poems and essays ridiculing Buffon. It would be most exciting if research could provide a complete understanding of the incognitum. In 1799, when Jefferson was president of the American Philosophical Society, he had distributed a printed appeal for an entire skeleton. Finally, a complete skeleton was found on a farm near Newburgh, New York, and it went on display in Charles Willson Peale's Philadelphia Museum in 1801.48

Jefferson celebrated Peale's exhibit, but he still wanted his own collection. When he briefed Meriwether Lewis for the Lewis and Clark expedition to explore the Northwest Territory, he asked him, on his trip down the Ohio River, to stop at Big Bone Lick and collect some of the bones for him. Lewis was a Virginia native serving as the president's private secretary. With Jefferson's approval, he selected as his cocommander Kentuckian William Clark, the younger brother of George Rogers Clark. Lewis and William Clark had served together as army officers in Indian fighting, and Lewis was familiar with Clark's skills and experience as a frontiersman. William Clark was born in Virginia, but his family moved to Louisville when he was about three years old, and he grew up on the Kentucky frontier. Lewis wrote to Clark inviting him to participate and asking him to recruit men for the Corps of Discovery. “Find out and engage some good hunters, stout, healthy, unmarried men, accustomed to the woods, and capable of bearing bodily fatigue in a pretty considerable degree,” he wrote. Clark signed up nine Kentuckians from the Louisville area, and they became famous as “Nine Young Men from Kentucky.” They made a vital contribution as hunters of game on the journey. The trek was so strenuous that a high-calorie meat diet was required, and they proved capable of providing six to nine pounds of meat per day for the thirty-three-man party. James J. Holmberg revealed that several of the soldiers added to the group later were from Kentucky and concluded that half the men in the expedition were Kentuckians or had significant connections to the state.49

Jefferson directed Lewis to stop in Cincinnati on his way to meet Clark in Louisville, to view and report on the Big Bone Lick bones in the enormous new collection of Dr. William Goforth, and then go to Big Bone Lick. Lewis visited Goforth in Goforth's home in Cincinnati and was impressed with the number of fossils; there were so many grinders that they filled a wagon, and the load was so heavy that four horses were required to pull it. The teeth, Lewis wrote Jefferson, “weigh from four to eleven pounds, and appear…precisely to resemble a specimen of these teeth” that he had seen in Philadelphia. Lewis visited the lick and collected a large tusk and two teeth and shipped them in crates down the Mississippi River. Jefferson was very disappointed to learn that the bones were lost when the boat sank at the landing in Natchez.50

Jefferson directed Lewis and Clark to study the animals in the Northwest and collect specimens, including any bones of the incognitum they might find. He expected and hoped that the Indian legend that the animals left Big Bone Lick for the northwestern wilderness might prove true and that the explorers would return with skins, skeletons, and tusks from a live herd. In a 1797 memoir for the American Philosophical Society, he wrote: “In the present interior of our continent there is surely space and range enough for elephants and lions.” In a letter written shortly before the expedition, he declared that Lewis and Clark might find living American incognitum.51

Lewis and Clark and the men Clark had recruited left Louisville on October 26, 1803, spent the winter preparing, and set off up the Missouri River on May 14, 1804. They collected and shipped to the White House animal skins and skeletons, including a few that were unidentified. They found no fossils of the American incognitum, and there were obviously no elephant-like animals alive in the Northwest. On September 23, 1806, they returned to St. Louis, and on November 5, 1806, William Clark and others returned to Louisville. Among the gifts that William Clark brought his family was a bighorn sheep horn for his sister Fanny Fitzhugh. It remained in the family until 1929, when family members donated it to the Filson Historical Society.52

Still determined to solve the mystery, Jefferson turned to William Clark. In January 1807, Lewis and Clark were reunited in Washington, DC, where they were welcomed as heroes. Jefferson was most pleased; having appointed Clark as Indian agent for the Louisiana Territory, he decided to ask him to lead an excavating party to Big Bone Lick. Clark agreed, and, on his journey down the Ohio River to take up his duties, he stopped in the area and employed ten laborers for the digging. They worked for several weeks, excavating three large boxes of bones that made it safely down the Mississippi River and up the East Coast.53

The shipment went safely through New Orleans, and, when the boxes were delivered to the White House, Jefferson was almost beside himself. At last, he had a large number of bones from the place that was the center of attention for naturalists. He had the crates unpacked and invited his friend Dr. Caspar Wistar to help him arrange and classify them. Wistar was a physician and fellow American Philosophical Society member who had been helping Jefferson research the mystery. Jefferson and Wistar determined that there were over three hundred specimens, including long-sought bones for the head. He now had four jawbones, numerous grinders, and several pieces of the head. At last, Jefferson's curiosity was satisfied. He came to the conclusion—as other naturalists were deciding about the same time—that the animal was a herbivore, that it ate plants, including small tree limbs. But the distinct knobby teeth set it apart as a new species different from the Siberian mammoth, which had smooth teeth. Now, having Lewis and Clark's report, he realized the American incognitum was extinct.54

Jefferson had financed Clark's excavation with his personal funds, so he was free to distribute the fossils as he wanted. He kept some and sent some to the American Philosophical Society in Philadelphia and others to the National Institute of France in Paris. He believed that the bones sent to Paris resulted at last in the naming of the American incognitum as the mastodon. Actually, it had already been named the year before by French naturalist Georges Cuvier, who wrote that it was extinct, different from living elephants and the Siberian mammoth, and so needed a new name. He named it the mastodon, from the Greek words for breast and tooth, since the protuberances on the grinders resembled a woman's breasts. One of Jefferson's visitors at Monticello in 1815 saw the head of a mastodon on the wall of his large room of collections of stuffed animal heads and Indian artifacts.55

Dinosaurs were not discovered and named until 1841, and until then the American mastodon ruled the prehistoric animal world in American popular culture. In January 1831, there was much excitement in Louisville over a new exhibit of Big Bone Lick fossils. Captain Benjamin Finnell, who lived near Big Bone, displayed the enormous collection he had taken from the site. It included twenty-two tusks, some nearly eleven feet long and weighing over five hundred pounds. Ignoring science, Finnell advertised that patrons could view the bones of a carnivorous monster with feet up to forty-eight inches long and a body twenty or thirty feet in height and nearly sixty feet long. Reporting on the exhibit, the Louisville Journal declared that the animal was king of the wilderness, “a mammoth among mammoths,” as cruel as a panther, as swift as an eagle, and as terrifying as the angel of death. It crushed pine trees with its feet, and, when it drank from a lake, the water level was lowered.56

In Big Bone Lick, the natural historian Stanley Hedeen demonstrates that Big Bone Lick was the birthplace of American paleontology. Cuvier completed the identification of the American incognitum, but it was established as an unknown animal by William Hunter on the basis of his study of bones from Big Bone Lick in the Tower of London. In 1936, Jillson pointed out that there were collections from Big Bone Lick in London, Paris, and Philadelphia and at the Smithsonian, Harvard University, Princeton University, and the University of Rochester. Today, he would have included Big Bone Lick State Park and the Behringer-Crawford Museum in Covington. In 2009, the National Park Service recognized Big Bone Lick State Park as a national natural landmark. Big Bone Lick had so many excavations and yielded so many bones that it had no rival in the solving of the mystery of the American incognitum.57

During his 1821 visit to Big Bone Lick, Rafinesque visited an Indian mound near the site and collected plants and fossils. He wanted to excavate for more fossils, but the owner prohibited digging under the mistaken notion that digging would dry up the mineral spring. At Transylvania, he displayed the fossils along with plant specimens and minerals in the university's natural history museum that he had established and for which he served as curator. He established the first botanical garden in the West, the Transylvania Botanical Garden, and led the state legislature as far as it was willing to go into natural science—he convinced the state Senate to approve a charter for the botanical garden, but the House of Representatives refused. Undaunted, he created a joint-stock company and sold shares, including two to Henry Clay. The garden company purchased a ten-acre lot on the south side of East Main Street, hired a gardener, and had trees planted. Rafinesque's goal was to teach farmers how to grow better fruit and profit from the cultivation of new vegetables, grains, rhubarb, castor beans for castor oil, and ginseng and to teach medical students how to use valuable materia medica, plants used in medicine. He planned to grow enough opium in the garden to cover expenses.58

His article on the Big Bone Lick visit was one of many. Indeed, he published at a frantic pace: over two hundred articles and many books, many of both published at his own expense. The problem was that Rafinesque was not respected by botanists in his day. They considered him a renegade—he did not follow the rules. He “disregarded the rules of classification and consciously or not, mocked the orderly and widely recognized system,” wrote his biographer Leonard Warren. He did not recognize in his writings the findings of predecessors; he did not credit them with their discoveries. He did not accept criticism, and, when a scholar criticized his work, he declared the person his enemy; he said that all his enemies were less intelligent than he. And it was most deadly to his reputation as a serious scientist that he declared unconfirmed myths to be scientific truth. He reported Audubon's imaginary fish as authentic, and he sometimes verified tales of folklore as scientific fact, as when he described a mythical one-hundred-foot-long Massachusetts sea serpent.59

Fellow Transylvania professors in the Medical Department treated him with cool forbearance, but some scientists who reviewed his writings called him a “crack-brained” quack engaged in wild speculations. He counterattacked by calling the regular physicians murderers who rejected curative plants in favor of poisonous drugs. He had measles while in Lexington and claimed that he recovered by avoiding their treatment. Rafinesque's magnum opus, however, reached out to the regular medical profession and attempted to inform doctors that in Kentucky they were surrounded by many plants valuable in treating their patients. Medical Flora; or, Manual of the Medical Botany of the United States of North America, published in 1828 and 1830 in Philadelphia, resulted from eight thousand miles of travel and fifteen years of research before, during, and after his years at Transylvania. Most of the collecting and classifying occurred in Kentucky during his tenure on the Transylvania faculty. His goal was to provide physicians, pharmacists, and people treating themselves valuable information about medical plants and helpful suggestions in their use. The two volumes were affordable and small enough to carry into the woods on collecting expeditions.60

Regular physicians attacked the book even though Rafinesque described the medical uses of many of the plants listed in keeping with regular medical practice of the time. But members of the botanico-medical movement, who advocated medical botany and challenged the regular doctors for using bleeding and harsh drugs, regarded the book with much respect and found it useful. It sold reasonably well and was Rafinesque's most profitable book. It identified ninety-nine medicinal plants and described how to use them. Forty-eight were listed as valuable in the first two official federal government drug and treatment manuals, the United States Pharmacopeia, published in 1820 and 1830. Fifty-one of the plants are used in medicine today, and the therapeutic value of many others is yet to be determined.61

In Medical Flora and other works, Rafinesque reported discovering, classifying, and naming sixty-seven hundred botanical specimens. David Starr Jordan declared him “the Daniel Boone of American science”; Leonard Warren concluded that he was “the first to describe—however imperfectly—and name a universe of plants and animals.” Medical historian Michael Flannery considers him a hero in the medical history of Kentucky and declares that Medical Flora “ranks as a major contribution to the literature of American medical botany.” Only in the late twentieth century with the rise of alternative therapies and their emphasis on herbal remedies has he become fully appreciated. Around 1900, leading botanists reevaluated him, and some of his plant names were recognized: 84 by one authority and 740 by another. In 1929, some of his plant species were included in the important Index Kewensis, a comprehensive list of the plants of the world. As Flannery has pointed out, Rafinesque found the flora of Kentucky rich in medical uses; not only have Kentucky plants had a powerful influence on the botanico-medical movement, but in the future systematic phytopharmaceutical researchers may also discover that the Kentucky plants he discovered may have therapeutic value.62

Horace Holley and his wife, Mary, were kind to Rafinesque, and they deserve credit for his staying at Transylvania as long as he did. They invited him to their home frequently and welcomed him warmly, which was important because he had few friends. He expressed gratitude by teaching Mary Italian and writing poems addressed to her. President Holley had the university grant him an honorary M.A. degree in 1822 and served with him as a fellow officer of the Kentucky Institute, the state's first scientific society—Holley was president and Rafinesque secretary. The incident that led to Rafinesque's resignation developed when he lost his focus and began spending his time on a bizarre banking scheme that he created. All his life, he had lived slightly above the poverty level, and he dreamed of creating a system that would make him and other poor people prosperous. He came up with his “Divitial Invention,” a savings bank that would divide its profits with small investors. Depositors would receive tokens to use as currency in the bank's branches. He took an unpaid leave from the faculty to go to Washington, DC, in the spring of 1825 to patent the idea and attempt to persuade eastern capitalists to invest in his bank.63

While Rafinesque was gone, enrollment continued to increase, and Holley needed space in the main building to house a student. Rafinesque had two rooms, one for his quarters and the other for his books, supplies, and collections. Holley had all his possessions moved into one of the two rooms. Rafinesque had been appointed librarian, and, while he was absent, he was removed from the position. When he returned, he was outraged and reacted by gathering his belongings and moving into lodgings off campus. He taught a course in botany in November 1825 and then resigned. He accused Holley of hating “science and discoveries” and pronounced a curse on him and the university. One of the themes of the Rafinesque legend today is the idea that the curse resulted, within a few years, in Holley's death of yellow fever and in the burning of the main college building.64

Rafinesque contributed to President Holley's introduction of science into the curriculum of the Academic Department, but Holley's greatest achievement—creation of an outstanding medical school with a national reputation—contributed to placing Kentucky in the center of scientific investigation in the nation. The Medical Department was created in 1799, but it lacked a complete faculty and a full program of instruction until the trustees reorganized it in November 1817 as part of their state university vision. The trustees hired several excellent medical professors. Holley's greatest recruit in the department was Dr. Charles Caldwell. Holley persuaded Caldwell to move to Lexington in 1819 from Philadelphia, where he taught at the University of Pennsylvania and had a national reputation as a teacher, writer, and public speaker. He was born in North Carolina and had an M.D. degree from the University of Pennsylvania. His main weakness was an attraction to theories that most scientists and physicians rejected, such as phrenology, the theory that bumps on the skull related to personality development. At Transylvania, he taught a course in phrenology but, nevertheless, inspired in his students “a love of science, and an ambition to excel,” according to his fellow medical professor Lunsford P. Yandell. Caldwell's greatest contribution to the university was as a fund-raiser—he was effective in convincing the state legislature and the city of Lexington to support the university. He has been criticized for focusing too much on the Medical Department and not raising adequate money for the Academic Department, but professors in the Academic Department used some of the teaching resources he acquired for the Medical Department. In 1821, having gathered thirteen thousand dollars for the purchase of books and instruments for the Medical Department, he went to London and Paris and made “one of the largest, if not the largest, purchases of its kind by an antebellum college,” according to Eric H. Christianson. When Holley arrived, the Medical Department had 37 students, and enrollment increased to 281 in the fall of 1825. By strengthening the faculty and providing first-rate equipment, books, and journals, Hol-ley gave the Medical Department a national reputation equal to that of the University of Pennsylvania and Harvard University. Indeed, under Holley, the Medical Department was the crown jewel in the Athens of the West.65

Similarly, Holley transformed the law school from a struggling institution with an inadequate faculty to a nationally respected department. He taught two courses on Blackstone at no charge and recruited several new professors, including former U.S. senator Jesse Bledsoe and William T. Barry, later Andrew Jackson's postmaster general, U.S. senator, and lieutenant governor of Kentucky. The greatest period of the Law Department began under Holley. Word spread throughout the nation that Transylvania University was an outstanding school, and many young men from the Atlantic states crossed the mountains into Kentucky for their college education. University enrollment increased from about seventy to over four hundred students from fourteen states in 1826. In January 1820, when Jefferson was preparing to create the University of Virginia, he recommended in the meantime that Virginia youths go to Transylvania in Kentucky or Harvard in Massachusetts, and he declared that of the two he preferred Transylvania because Kentucky was more similar to Virginia in culture. The university had 383 students in 1821, more than Harvard or Yale. From Mississippi came young Jefferson Davis, and, when he served in Congress, he counted seventeen Transylvania classmates serving in the House and Senate.66

One of Holley's successes was public engagement with Lexington and the Bluegrass community. Fathers and mothers appreciated that women could enroll in individual classes, and people enjoyed attending public lectures by the professors on campus. The faculty gave lectures to the public on subjects such as chemistry, natural history, geology, and agriculture. The Lexington city government supported the university with six thousand dollars of the money for Caldwell's purchase, and the citizens raised three thousand dollars for faculty salaries. The public, faculty, and students under Holley supported science in the curriculum and, throughout the history of the institution, have maintained strong support of the school.67

Holley realized that employing a great faculty, creating first-rate medical and law schools, and providing equipment to teach science courses would be expensive, and, when he accepted the presidency, he expected that state funding would be forthcoming. There was a honeymoon with the state legislature for a couple of years, but the national panic and depression of 1819 and its political fallout in Kentucky brought an end to the dream. From 1818 to 1822, the legislature appropriated $11,935 to its state university, almost half of which was the five-thousand-dollar grant in 1820 “for the specific purpose of purchasing books and apparatus” for the Medical Department. Yet the depression was the worst in the nation's brief history, and Transylvania University and Horace Holley became whipping boys in the bitter political contest between those favoring debtor relief and those opposed. Henry Clay attempted to remain above the fight, but the relief forces portrayed him as antirelief, and he was. Since he was a friend of Holley's and a trustee of the university, the Relief Party attacked Transylvania and Holley as part of its attack on Clay. The Relief Party identified with Andrew Jackson and egalitarianism, and it succeeded in portraying Holley and the university as elitist.68

Given the depression and the New Court (Relief)-Old Court (Anti-Relief) controversy, it is remarkable that Transylvania was funded as well as it was. In addition to the $11,935 for the Medical Department, in 1821, when the university was $26,000 in debt, the legislature appropriated $20,000 from the profits of the Bank of the Commonwealth of Kentucky. Caldwell and Holley had done well in obtaining this money, but it came with a slap on the wrist—the legislature warned Transylvania not to get into debt again. Holley realized that further state support was unlikely. When the relief forces won majorities in the legislature and the relief advocate Joseph Desha was elected governor in 1824, Holley went to Frankfort and lobbied for Transylvania, but he was treated coldly in comparison to how he was welcomed earlier. When Desha addressed the legislature in November 1825, he declared that Transylvania was not a school of the common man. “It seems that the State has lavished her money for the benefit of the rich, to the exclusion of the poor,” he said. He exaggerated the level of support that had been given and condemned Holley for living in a home furnished by the university and accepting a salary of three thousand dollars a year, twice that of the governor. The next month Holley pointed out that the state was refusing to support its state university, and he resigned.69

Meanwhile, since February 1819, Holley had come under a fierce social and theological attack by leaders in the Presbyterian Church. They accused him of delivering sermons to the students in chapel that proclaimed Unitarian theology. They accused him of playing cards, going to horse races, dancing at ballroom dances, and approving theater productions by the students on campus that he attended. Holley was extremely popular in Lexington, and his friends answered that he attended races, dances, and the theater but that he did not play cards. He was so popular in the city that Lexington newspapers would not print the attacks; they were published in out-of-town newspapers. Part of community relations for Holley was entertaining in his home, and there were parties for James Monroe, Andrew Jackson, the Marquis de Lafayette, and other visiting dignitaries, and many evenings groups of students were invited to his home for concerts. Holley's enemies condemned these parties for corrupting the students with secular songs. One evening, one of the attackers reported, a group of students left in protest because the music was secular.70

The trustees accepted Holley's resignation and persuaded him to remain another year. Finally, in the spring of 1827, he and his family departed for New Orleans, where he was planning to start a new school. That summer the heat was oppressive, and, for relief, he and Mary and their young son, Horace Austin, left on a ship for New York. Holley contracted yellow fever and died at sea on July 31, 1827, at the age of forty-six. He was buried at sea off the Dry Tortugas. After the glorious days of President Holley, Transylvania's professors still taught science with outstanding library holdings and up-to-date scientific apparatus, and the Medical Department continued educating physicians who treated thousands of patients, but medical education began a lengthy, gradual decline in the state.71