CHAPTER 4

If It’s Called “Arctic Spring,” Why Is It from Florida?

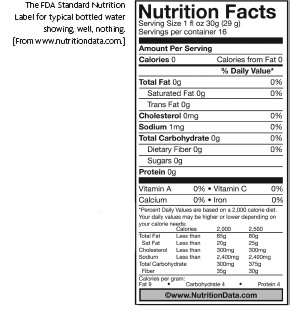

Calories, 0; Fat, 0; Cholesterol, 0; Sodium, 0;

Total Carbohydrate, 0; Protein, 0.

—Typical information on a bottled water

label in the United States

“Alaska Premium Glacier Drinking Water: Pure Glacier Water from the

Last Unpolluted Frontier” was actually drawn from Public Water System

#111241 in Juneau.

—Brian Howard, E—The Environmental Magazine1

ONCE UPON A TIME, when you bought Poland Spring bottled water it actually came from the famous Poland Spring in the state of Maine. Today, Poland Spring is no longer a “source” but a “brand.” The water in the bottle might come from Poland Spring, or it might come from Clear Spring, Evergreen Spring, Spruce Spring, Garden Spring, Bradford Spring, or White Cedar Spring—other Maine water sources owned by Nestlé Waters North America. There is no way to know. And Nestlé isn’t saying.

Poland Spring water has a long history. In 1845 the Ricker family began to bottle local spring water. They sold it in grocery stores in clay jugs—three gallons for 15 cents—and wooden barrels to sea captains and other travelers. By 1860 claims of health benefits, paid advertisements, and word of mouth had increased sales substantially, and Poland Spring water was being sold as far away as “the Deep South and the Far West.” In 1895 the water won top honors “over all the other waters of the world” at the Chicago World’s Fair. It won the Grand Prize for water at the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair, and the Ricker family went on to build bottling houses and a major resort that hosted celebrities such as Mae West, U.S. presidents Cleveland and Taft, and business leaders. Demand continued to grow throughout the twentieth century, putting more and more pressure on the limited flow of the original spring. There were rumors that the spring stopped flowing in 1967 because of excessive pumping of the groundwater feeding the spring.2 In 1980 The Perrier Group, later to become Nestlé Waters North America, purchased Poland Spring as one of their flagship brands, which also include Perrier and Arrowhead Spring. By the early 2000s sales of Poland Spring water exceeded $600 million a year and the demand for water had skyrocketed. In order to keep up, Nestlé had to find other sources of supply, and the name “Poland Spring” became a “brand” rather than a specific source.

Not all consumers were happy with the change. A class-action lawsuit filed in Connecticut Superior Court in 2003 contended that Nestlé was guilty of false advertising by implying on their labels that the water comes from Poland Spring.3 The suit alleged that the production of Poland Spring depends on source wells drawing more than six million gallons of water a year, none of which comes from the original Poland Spring, and some of which are vulnerable to surface contamination. Similar suits were filed in Massachusetts and New Jersey Superior Courts. Without admitting to any wrongdoing, in September 2003 Nestlé Waters agreed to settle this class-action suit, step up quality control, and pay $10 million over five years in discounts to consumers and contributions to charities—but there was no requirement that they clarify their labels.4 In 2009 I asked a representative of the company what fraction, if any, of Poland Spring water now comes from the actual Poland Spring, how much Arrowhead Spring water is in Arrowhead brand bottled water, and how much real Perrier Spring water is in the Perrier brand bottled water? After several months and communications, as this book was going to press, the company had still refused to release this information.

What is really in the water bottles we buy? We know, or hope, that it is water, but it turns out we rarely know what kind of water it is, or precisely where it comes from, even if it has a famous name or historical association. We assume—perhaps mistakenly—that it is clean and safe to drink, but we don’t know how it was treated, who tested it, or what the results were. We want it to taste good, but we aren’t told details of the mineral composition, which determines the actual taste.

All we know is what we’re told on the label, and what we’re told on the label in the United States is minimal and misleading. What might a good water bottle tell you? Should it clearly and honestly describe what kind of water is actually in the bottle? Which spring or municipal system the water comes from? What kind of purification treatment, if any, it has received? Should the label accurately specify the detailed mineral composition of the water, which affects the taste? And finally, what if labels told the consumer where to go to get up-to-date information about where to see detailed water-quality tests, to ask for more information, or to file complaints?

Current bottled water labeling laws in the United States require none of these things. There are rules in the U.S. about some of these things, but these rules are inconsistent and inconsistently applied, and bottled water labels often do more to conceal information than reveal it. In order to provide at least some help for consumers, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration is supposed to oversee a set of labeling rules that apply to some (though not all) of the bottled water sold in the United States. First of all, the FDA defines bottled water as “water that is intended for human consumption and that is sealed in bottles or other containers with no added ingredients except that it may optionally contain safe and suitable antimicrobial agents.” So no added ingredients. (“Vitamin waters” and other “enhanced” water drinks are considered to be more akin to carbonated soft drinks or fruit drinks.)

The FDA further restricts the names that can be used to describe the water—not the commercial brand name, but how the kind of water itself is to be identified.5 This name is called the “identity.” According to the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FFDCA): “A bottled water product must meet the appropriate Standard of Identity and bear the required name on its label or it may be deemed misbranded under the FFDCA.”6

The most common Standards of Identity are shown in the box on the next page. But don’t expect these names to offer much enlightenment. Despite, or maybe because of, the great diversity of these “identities,” the average buyer is unlikely to understand the differences among “distilled,” “deionized,” and “purified,” or among “well,” “spring,” ground,” and “artesian” water. And consumers deserve to know much more.

In contrast to U.S. labeling requirements, the European Community requires that labels on natural mineral waters and spring waters sold in Europe include the following mandatory information:

(a) A statement of the analytical composition, giving its characteristic constituents,

(b) The place where the spring is exploited and the name of the spring, and

(c) Information on any treatments used to process the water before bottling.7

The failure to provide clear labels on U.S. bottled water leads to consumer confusion. Arrowhead Spring Water, for example, also bottled by Nestlé, used to come from the actual Arrowhead springs on the slopes of the San Bernardino mountains, but now, like “Poland Spring,” it is just a brand name for water that comes from many different springs across southern California. Nestlé has even proposed tapping a spring in Colorado and calling it Arrowhead.8 Consumers no longer know the specific source of the water in the bottle they buy or if it is from a mix of sources.

U.S. “Standards of Identity” for U.S. Bottled Waters

“Artesian water” or “artesian well water” is water from a well tapping a confined aquifer in which the water level stands at some height above the top of the aquifer. Artesian water may be collected with the assistance of external force to enhance the natural underground pressure.

“Ground water” includes water from a subsurface saturated zone that is under a pressure equal to or greater than atmospheric pressure. Ground water “must not” be under the direct influence of surface water as defined by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA),* though determining “direct influence” is dicey, at best, as I discuss later.

“Mineral water” is water containing not less than 250 parts per million (ppm) total dissolved solids (TDS), coming from a source tapped at one or more bore holes or springs, originating from a geologically and physically protected underground water source. No minerals may be added to this water. If the TDS content is below 500 ppm, the label is supposed to say “low mineral content”; if the TDS content is above 1,500 ppm, the label should read “high mineral content.” There is no requirement to list the individual minerals or their concentrations.

“Purified water” is water that has been has been treated by distillation, deionization, reverse osmosis, or other “suitable processes,” and that meets the definition of “purified water” in the United States Pharmacopeia (twenty-third revision). Major bottlers like Coca-Cola, Pepsi Co, Nestlé, and others produce and sell “purified water” that often originates from municipal water systems.

“Sparkling bottled water” is water that, after treatment and possible artificial replacement of carbon dioxide, contains the same level of carbon dioxide as water directly from the source.

“Spring water” is water derived from an underground formation from which water flows naturally to the surface of the earth. Spring water is to be collected only at the spring or through a bore hole tapping the underground formation directly feeding the spring.

“Sterile water” is water that meets the requirements under the “Sterility Test” in the Twenty-Third Revision of the United States Pharmacopeia.

“Well water” is water from a hole bored, drilled, or otherwise constructed in the ground, which taps the water of an aquifer.

* In the Code of Federal Regulations, 40 CFR 141.2

Even when the water comes from a municipal water supply, which is increasingly the case, the bottler does not have to state which one, or describe whether or not the water goes through additional processing. Coca-Cola’s Dasani, Pepsi Co’s Aquafina, and Nestlé’s Pure Life brands come from dozens of different bottling plants, which treat local municipal waters so they all taste the same. If you buy Dasani in the San Francisco Bay Area, you’re probably getting water bottled at their plant in San Leandro. Buy Dasani in southern Michigan and it probably originated as municipal water in Detroit. But the bottlers don’t have to say and they often package their bottle in a way to draw on the cachet of spring water.

Until mid-2007 bottles of Aquafina offered no indication that the water originates from local tap water systems, and even today it has a lovely logo designed like a mountain range. Curious consumers might have seen a small “P.W.S.” on the label, but until advocacy groups pressured the company to actually spell out “public water source,” most consumers probably had no idea that they were drinking reprocessed tap water. In announcing the change, Pepsi Co spokeswoman Michelle Naughton spun, “If this helps clarify the fact that the water originates from public sources, then it’s a reasonable thing to do.”9 At the same time that Pepsi Co announced their intention to modify their labels, Nestlé announced it would be changing its labels to “identify the source of the water, whether it’s from a municipal supply or ground-water well source.”

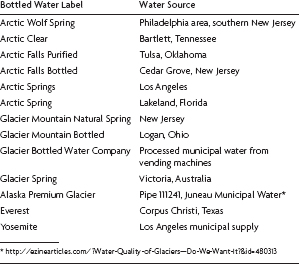

Other and more egregious naming abuses abound (see the table below, “The Water Comes from Where?”). “Arctic” is a hugely popular name for bottled water, symbolizing the legendary purity of the far frozen (albeit now rapidly melting) north, as are pictures and graphics of pristine frozen wildernesses or snow-covered mountain tops. Yet “Arctic Spring” water comes from Florida, while “Arctic Falls Bottled Water” and “Arctic Wolf Spring” brands come from New Jersey. “Arctic Falls Purified Water” is from Oklahoma and “Arctic Clear” from Tennessee. The consumer might reasonably expect that any bottled water with the name of Glacier would be lovingly collected by hand at the melt face of a pristine wilderness ice field, but no, sorry. “Glacier Mountain Natural Spring Water” is bottled in New Jersey. “Glacier Mountain Bottled Water” comes from Logan, Ohio, southeast of Columbus. The last time glaciers were seen in what is now New Jersey or Ohio was more than 10,000 years ago. The “Glacier Bottled Water” Company sells filtered municipal water from vending machines at grocery stores. Even “Alaska Premium Glacier” bottled water apparently came from the municipal water system in Juneau, “specifically, pipe # 111241.”10 At least it’s really from Alaska, for whatever that’s worth.

The Water Comes from Where?

These kinds of misleading names aren’t the exception—they seem to be the rule. “Yosemite” brand bottled water comes from the Los Angeles municipal water system. “Everest” brand water, complete with a picture of a tall snowy mountain on the bottle, comes from southeastern Texas, and while there are many big things in Texas, Mount Everest isn’t one of them.

Don’t expect regulators to step in and challenge these kinds of misrepresentations. Even with the FDA Standards of Identity, there are almost no requirements for truth in branding. Thus, a bottler can name a product “Glacier Bottled Water” but cannot call it “glacier water.” Even the made-up names of Dasani and Aquafina are created by branding companies based on the responses of focus groups. When asked what the name “Dasani” means, Coca-Cola executives described consumer testing that “showed that the name is relaxing and suggests pureness and replenishment.”11 Is there any surprise consumers are easily fooled and misled?

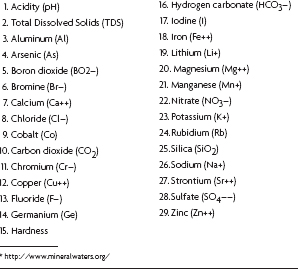

So what is taking up all the space on the label? Other than graphic images of mountains or water or company logos, there is one more major component to a bottled water label in the United States—the standard FDA nutrition table. Because bottled water is considered a food product, the FDA requires bottlers to include the general “Nutrition Facts” food label on the bottle. We’ve all seen this standard label on food packages, which requires information be provided to the consumer on a range of things, from calories to fat content to vitamins. For real food, these labels can be useful. Not for water. Note the “information” on one such label that appears on a typical water bottle. No calories, no fat, no cholesterol, no sodium, no carbohydrates, no sugars, no protein, no vitamin A, no Vitamin C. Well, duh. None of these things are found in water. But there are things in water, lots of things. Even very clean and safe water has lots of dissolved minerals in it, and the composition of these minerals plays an important role in taste. By requiring bottled water in the United States to apply the standard food label, bottlers and regulators are misleading consumers about the safety, quality, and composition of that product, while at the same time failing to provide any useful information about what kinds of minerals are actually present. Compare the U.S. FDA label with the information typically presented on bottled waters in Europe, shown on page sixty-one.

More than a decade ago, the FDA concluded that it would be “feasible for the bottled water industry to provide the same type of information to consumers that the Safe Drinking Water Act requires” of public water systems, but they have taken no action to require the industry to do so, and apparently have no intention at present to do so.12 There have been various attempts to strengthen and expand the kinds of information provided on water bottle labels, but these have almost always been beaten down by the industry. One recent example is California, which, in 2007, modestly tried to expand the information provided to consumers on water bottles, with bills from both the State Assembly and Senate. One provision of the Senate bill required that, as of January 1, 2009:

Each container of bottled water sold at retail or wholesale in this state in a beverage container shall include on its label, or on an additional label affixed to the bottle, or on a package insert or attachment, all the following:

(1) The name and contact information for the bottler or brand owner.

(2) The source of the bottled water, in compliance with applicable state and federal regulations.

(3) A clear and conspicuous statement that informs consumers about how to access water quality information…. 13

The bill was supported by a broad coalition of consumer and community groups, public interest organizations, water utilities, and government agencies, including the Consumer Federation of California, the Association of California Water Agencies, the California League of Conservation Voters, Environment California, the Sierra Club, Environmental Defense, the Natural Resources Defense Council, Latino Issues Forum, the San Francisco Public Utilities Commission, and many more. Weak as it was, it was opposed by the California Bottled Water Association, California Chamber of Commerce, California Grocers Association, and the International Bottled Water Association. Why? The IBWA argued that “there has been no consumer demand for such measures,” despite the fact that consumer groups strongly supported the California bills.14 Some bottlers and representatives of the FDA tried to argue that there is not enough room on the label for this information, or that it would be too complicated or expensive to changes labels, even though some bottlers seem to find plenty of space and money to prepare fancy labels.15 Nestlé Water North America actually has nine separate messages rotating through their bottled water labels, bragging about how environmental they are, how little plastic their eco-friendly bottles use, and so on.16

Mineral Constituents Typically Listed on European Mineral Water Labels*

The California legislature passed both bills, and Governor Schwarzenegger signed the Senate bill into law on October 13, 2007. While the new labels were supposed to be in place by January 2009, as of March 2009 many bottles of water on the shelves of my supermarket still lacked the new labels. Until better regulations on labeling are put in place, and are properly enforced, consumers will remain in the dark about what’s really in the bottles of water we buy.

Ultimately, consumers should ask why bottled water is considered a “food” in the first place and whether it would make more sense to treat bottled water as, well, water, with the same rules, protections, and safeguards as tap water. A perfect example of the confusion generated by the FDA’s regulations is the unusual case of “spring water.” This class of bottled water dominates the U.S. market and consumers seem to prefer the cachet of spring water to processed municipal waters. But is it any better tasting or any safer? In order to answer this, we must first understand what spring water is and where it comes from.