The Hunger Games films appeared in a context in which what happens in a movie theatre has become only one aspect of cinema, and in which the once tight connection between youth culture and cinema has been dispersed by closer associations between youth and other media. A presumption that young audiences are key to the commercial success of any major film nevertheless remains crucial to the Hunger Games. As we have argued, the Lionsgate films sought to leverage youth-oriented conventions within the blockbuster action genre, but the importance of the pre-existing fandom of the YA novels also needs to be considered here. This fandom brought its own interpretative debates to reception of the films, impacting not only the scale and breadth of their success but the kinds of marketing and merchandising that would work for this franchise. Moreover, the discourses on gender and (im)maturity that pervade fan practices are relevant to the life and afterlife of the franchise.

A now long history of scholarship offers widely varying accounts of what fandom offers fans, and how they relate to the objects they admire.1 These range from ideologically blind immersion in the culture industry, as theorised by Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer in the 1940s (2002), to the integration of consumption into media production in the figure of the ‘prosumer’ (Jenkins 2006). Henry Jenkins claims he has ‘watched fans move from the invisible margins of popular culture and into the centre of current thinking about media production and consumption’ (2006: 12). While cultural producers have long tracked fan activity, in recent decades they have increasingly taken up fan media for promotional purposes in ways that complicate the relationships between fans, producers, and products. Whether understood as ‘transmedia’ assemblage or as signs of ‘post-cinema’ dispersal, fan practices of popular citation have played a crucial role in the Hunger Games franchise.

Scholarship on cinematic images of youth has often focused on the way films reflect the changing experience of adolescence in the world from which they emerged. Sometimes this argument traces broad changes in the evolution of popular cinema, but often it is focused on more specific youth experiences, periods, or locations. As most spectacularly successful examples of youth cinema are American, most scholarship has focused on American adolescence, and the Hunger Games, too, is shaped by many American tendencies in stories about youth. There is nevertheless a more general set of issues at stake. Timothy Shary argues that cinema has seemed especially able to capture ‘the nature of adolescence’ and specially exemplary of ‘youth culture’, ‘fluctuating on a continual basis with the various whims of time’ (2014: 1). However, the relation between youth on screen and youth in the audience has clearly changed since the 1980s’ ‘Generation Multiplex’. As John Belton records (2014), decades of film criticism have seen signs of cinema’s decline in new forms of audiovisual culture, including new modes of filming, editing, projection, and distribution. Drawing on Rick Altman’s account of this ‘crisis historiography’, Belton argues that cinema should was always not ‘a single stable object of study but a site where its identity is always under construction’, dependent ‘on the way users develop and understand it’ (2014: 463). This chapter foregrounds relations between what is traditionally cinematic about the Hunger Games and its extensions into other modes of cultural production, from advertising to fan practices, focusing on the politics of genre and image that unite the franchise.

We cannot understand a transmedia franchise like Hunger Games by focusing only on its official published texts. Of course, we might analyse one, or the set, of the Hunger Games films without reference to the books, let alone to fan productions or the critical commentary that surrounds, informs, and responds to them. But what we want to call the affective map offered by the Hunger Games unfolds further than that, and draws its impact from elements beyond any precise textual component. We take the term ‘affective map’ from the work of Steven Shaviro. Summarising his book on Post Cinematic Affect (2010), Shaviro notes that:

Cinema is generally regarded as the dominant medium, or aesthetic form, of the twentieth century. It evidently no longer has this position in the twenty-first. So I begin by asking, what is the role or position of cinema when it is no longer what Fredric Jameson calls a ‘cultural dominant,’ when it has been ‘surpassed’ by digital and computer-based media?

(Shaviro 2011)

The book itself answers this question with the ‘affective map’ idea, treating ‘media works’ as ‘machines for generating affect, and for capitalizing upon or extracting value from, this affect. As such, they are not ideological superstructures, as an older sort of Marxist criticism’, like Adorno’s, ‘would have it’ (Shaviro 2010: 3). Rather, such works ‘lie at the very heart of social production, circulation, and distribution’ and centrally gain their effectiveness from the ‘affective labour’ of consumption (3–4). Our use for Shaviro here is to stress that textual analysis alone cannot capture how films work as ‘affective maps, which do not just passively trace or represent, but actively construct and perform, the social relations, flows, and feelings that they are ostensibly “about”’ (6). Attention to what matters to expected and actual audiences is important for understanding how the Hunger Games films are affected by their generic, historical, and industrial context.

Images of youthful promise and rebellion have long been key drama for cinema. In numerous films, especially those seeking a youth audience, youthful screen rebels resist limits and oppressions in their personal lives, or built into the institutions that train and monitor them. Such films range from sex comedies to art drama. There is often, however, an inverse relation between the scale of the risks faced by young protagonists and a film’s generic realism. For example, there may be grim personal consequences in youthful gangland drama, with a measure of social commentary framing the risks involved, but when focusing directly on large-scale social harm, realism is generally qualified, either by satire (Election [Payne 1999]; Dear White People [Simien 2014]) or by a measure of fantasy which allows young people to improbably bear the burden of social resistance (Red Dawn [Milius 1984]; Tomorrow When the War Began [Beattie 2010]). The latter approach encompasses speculative cinema and its televisual equivalents. Stories of youth in war zones are thus not often adapted to youth cinema. This is partly because of the restrictions on images of young people as subjects or objects of violence imposed by internationally connected national censorship and classification systems (see Cole, Driscoll, and Grealy 2018). These systems presume that realistic violence risks disturbing the young, whereas fantasy violence is part of expected genres for young people, from fairytales and comic books to film and television. Realistic images of youthful violence are also presumed to present dangerously imitable acts that immature minds are not equipped to put in context. A further reason for avoiding realistic violence is the generic convention that young heroes are singularly exceptional, which tends to exclude realistic war stories.

Both fantasy and realism are key to the integration of speculative and youth cinema. Horror and science fiction were crucial among the new subgenres of youth cinema that emerged in the 1950s, as film industries struggled with challenges posed by television and suburbanisation and strove to capitalise on the newly visible distinctiveness of youth culture (Doherty 2002). Both Doherty and Mark Jancovich (1996) have stressed the importance of young audiences for monster movies at this time, with Doherty foregrounding Hollywood exploitation of youth as its key audience demographic, and Jancovich focusing on its allegorical dimensions, including its capacity to represent psychosocial adolescent drama. On the side of science fiction, technology offered similar opportunities to speculate on selves, bodies and societies in states of becoming, as Elizabeth Hills suggests in her work on the machine-human assemblage as action hero (discussed in chapter two). Both monster and science fiction film have thus influenced how youthful speculative literary heroes are adapted to film, but the Hunger Games novels were not only science fiction but also gothic romance, and this, as well as their blockbuster action style, must be considered in any assessment of the films’ audience. Speculative worlds are necessarily incomplete, leaving considerable room for alternative audience investments and interpretations, making such media works more amenable to generating dedicated fandoms. Any overview of fan hubs, on social media or websites, demonstrates how speculative fiction dominates media fandom. The ‘endlessly deferred narrative’ of sci-fi and fantasy ‘creates a trusted environment for affective play’ (Hills 2002: 104), which is both a draw for individual fans and the premise of practices that extend the text’s scope far beyond its initial conception.

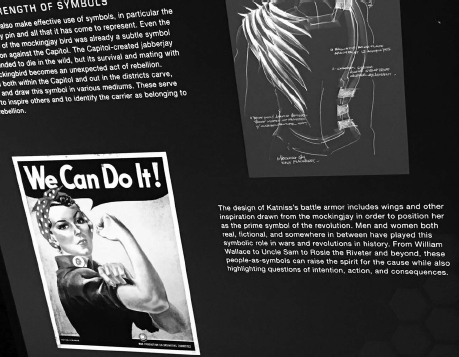

From July 2015 to March 2017, a Lionsgate-licensed exhibition on the making of the Hunger Games films (Figure 5.1) travelled across four locations, from New York City to Louisville, Kentucky (Jennifer Lawrence’s hometown), via San Francisco and Sydney, Australia (where both authors of this volume live).2 While the massively successful travelling Harry Potter exhibition was its likely model (launched April 2009 and still touring at the time of writing), the pedagogic design of the Hunger Games exhibition was somewhat misplaced for an audience not centred on families with children. It was also dominated by a large merchandise emporium somewhat at odds with the franchise’s political narrative. Despite such problems, there was much to interest us in this exhibition, which focused on production (especially costume) design but had a final room displaying the results of a fan-art competition. Most of this art clearly interpreted the Hunger Games through the lens of the Lionsgate films, but it also demonstrated that the franchise overall depended heavily on the fanbase for the Collins novels.

The Hunger Games Fandom Wiki (http://thehungergames.wikia.com) has had a much longer life, beginning with fans of the books and still generating daily updates to its fan feed. Like other Hunger Games fansites, it indicates overall consistency with the workings of other popular media fandoms. Shared knowledge is key, including knowledge accumulation like this wiki, which juxtaposes the novels and films while also distinguishing between them, and features fan shorthands like ‘D12’ for District 12. Socialisation is also important, including social media links. In fan productions, the usual pairing attachments and related conventions are apparent, demonstrating diverse and sometimes competing interpretations of the narrative. While most fan paraphernalia (licenced and otherwise) focuses on Katniss, fanfiction always encourages specialisation, niche subcommunities, and experiments with story variation. Disagreements are thus as important as consensus (Johnson 2007), including over the correct pairing for Katniss, or even what to call key ‘ships’ (short for relationships). For example, serious Katniss/Peeta shippers tend to use Everlark, but Peeniss is also used, usually to satirise the pairing.3 While the films now dominate visualisation of the story, the differences they introduced are frequently marked, and widely disparaged in some fan communities even as fan knowledge has sometimes been overtaken by the films and canonised by Collins’s role as co-producer. One example is speculation over how the map of Panem would exactly correspond to the contemporary US, which Film 2 ended with the authorised map (Figure 1.1) that was then incorporated into the exhibition.

The pleasure in exhaustively knowing a world which attracts fans to speculative fiction strengthens associations between fandom and immaturity, but the pleasure in textual immersion and shared passion has also been particularly associated with women (e.g. Radway 1984). As Joli Jensen points out, there have long been two dominant images of the fan – ‘the obsessed individual and the hysterical crowd’ (1992: 9) – respectively associated with youth and femininity. Girls have thus seemed like archetypal fans, as in Adorno, or in later studies of pop music and fanfiction (Hills 2002: 73), although many devoted fans are actually older women, even for YA franchises (e.g. Dorsey-Elson 2013). Jensen argues that the pathologisation of fans which sees them as immature ‘is based in, supports, and justifies elitist and disrespectful beliefs about our common life’ and cuts us ‘off from understanding how value and meaning are enacted and shared in contemporary life’ (1992: 26). But while taking fan practices as key elements of the Hunger Games franchise aligns with some key tenets of media studies, blockbuster films have also typified another kind of hierarchy – a critical framework that positions ‘spectacle versus narrative’ and ‘merchandizing versus authentic art’, with ‘each opposition [restaging] a clash between valued culture and devalued economy’ (Hills 2003: 181). The presumption that the appeal of blockbusters is ephemeral and inauthentic is shifted by a fan focus given that the ‘cult blockbuster’ is built on durable fan investments (182) rather than being merely an ‘“event” movie’ (183).

The blockbuster category gained new currency in the 1970s and 1980s, referring to massively successful films such as Jaws (Spielberg 1975) and Die Hard (McTiernan 1988), redefined, as Geoff King argues, by their ‘intensity’ and ‘abundance’ (2003: 118) – terms he takes from Richard Dyer’s account of entertainment film utopia discussed in chapter four. They also had at least a superlative relation to realism. Action and speculative film genres each provide additional opportunities for intense and abundant special effects. Fantasy and science fiction themselves emphasise novelty, while also offering additional rewards for fans who collectivise around interpretation of media works, and are in turn inclined to repeat viewings and an array of profit or publicity-generating fan activities (Jenkins 2006). While t-shirts and posters have been licenced to promote Jaws and Die Hard, authorised merchandising for the Hunger Games was not only much broader but prioritised youth, from dolls (Figure 0.1) and school supplies to makeup ranges. The youth- and female-oriented demographics of the franchise’s durable fanbase is also evident in fan productions shared, traded, and sold among fans.

Although fans have often been viewed as obsessive, and have often regarded themselves as gatekeepers to properly discriminating appreciation of their fan objects (Hills 2002), recent scholarship has followed the lead of writers like Hills and Jenkins in stressing the increased intersection of consumer/fan roles and consumer/producer roles. ‘While simultaneously “resisting” norms of capitalist society and its rapid turnover of novel commodity,’ writes Hills, ‘fans are also implicated in those very economic and cultural processes’ and the conventional opposition ‘between the “fan” and the “consumer”, falsifies the fan’s experience by positioning fan and consumer as separable cultural identities’ (2002: 29). Jenkins further complicates producer/consumer oppositions by focusing on the diverse ways producers now aim to engage fan attachment, and all these complications are apparent in fan relations to the Lionsgate films. They are also shaped, for many fans, by the Hunger Games’ internal story about the politics of media consumption.

An impressively diverse range of Hunger Games fan productions is (still) available on hubs like etsy, redbubble, or cafepress, or tagged on Pinterest: replica costumes and accessories from the films; fan art on myriad surfaces, from posters to water bottles and phone cases; clothing and accessories bearing images from or commentary on the books/films; and homewares like cushions, bath salts, and cookie cutters. The crossovers between fan-product and producer-product to which Jenkins points in Convergence Culture (2006) are very apparent, including licencing of a Hunger Games ‘store’ on cafepress and, perhaps most significantly, the forms of fan interactivity built into Lionsgate’s promotional website, Capitol.pn, which even coined a URL extension for the nation of Panem (see frontispiece).4 Lionsgate courted fans in complex ways through this site, which leveraged an extensive fanbase using proven digital fan-exploitation tactics. A key entry point to Capitol.pn was assignment of an official ID that allocated that user a home ‘district’. While the ‘sorting hat’ on the Harry Potter fan extension site, Pottermore (www.pottermore.com), requires answers to a quiz, ostensibly reflecting the user’s personality, Capitol.pn replicated Panem’s structural inequity and randomly assigned these districts. Once a member, fans could learn more about their district (and others) and also read the polished design magazine Capitol Couture, which featured the work of costume, makeup, and set designers, while also reflecting the hyper-stylised lifestyle of Capitol residents.

The Capitol.pn site changed to match the film series narrative – first becoming an explicit propaganda tool for President Snow, but eventually taken over by the rebels and renamed resistance.pn (the frontsipiece uses one of the new images this involved). New participatory elements were also introduced across this campaign, from hashtags like #ohsocapitol to the opportunity to digitally tag buildings with Mockingjay symbols (Bourdaa 2016: 96). Hannah Mueller credits the commercial acumen and fan engagement in this strategy:

This kind of storytelling across different media requires audiences to trace all the narrative threads on different platforms if they want to feel like they have all the relevant knowledge, and it rewards those who do with the feeling of being part of an interpretative community of insiders. At the same time, transmedia storytelling facilitates brand loyalty, because it forces consumers to engage with or buy different products associated with the brand.

(2017: 140)

Content was often linked to additional opportunities for fan consumption, so that, for example, Katniss’s superficial branding as a fashion designer within the Book/Film 2 storyline was linked to a licenced clothing line available for purchase (Bourdaa 2016: 95).

Many fans responded positively, with sites like ‘Welcome to District 12’ excitedly tracking changes (www.welcometodistrict12.com/p/communicuff.html). But as the fan commentary on Tumblr scrolling down the side of that site indicates, fans also debated the appropriateness of such marketing. Melanie Bourdaa stresses antagonism between the Capitol.pn channelling of fan enthusiasm and what she calls ‘fan activism’, by which ‘fans “took back the narratives” and focused their energies towards something more meaningful to them’ (2016: 90). This included objecting to appropriation of fans’ local activities to promote the Lionsgate product in ways that ironically mirrored how the Capitol uses the lives of district tributes. Bourdaa particularly targets ‘fanadvertising’ – content produced by fans, like hashtagged Instagram photos, and incorporated into the campaign as a form of unpaid ‘digital labour’ (100). Both Mueller and Bourdaa note real-world activists using the three-finger salute popularised by Katniss, sometimes with serious consequences. But fan activism more usually focused on articulating links between the story and real-world politics. Bourdaa highlights the Harry Potter Alliance’s campaign, which used the Hunger Games films to promote consciousness of poverty and hunger: tackling ‘economic inequality on several levels as well as the disparity between the Hunger Games franchise’s poignant content and its vapid, exploitative marketing strategy’ (The Harry Potter Alliance 2015). HPA’s message that ‘the hunger games are real’ belonged to a broader position, addressing many fandoms, that ‘fantasy is not only an escape from our world, but an invitation to go deeper into it’ (2015). Their Tumblr campaign, like Capitol.pn, mirrored the structural impoverishment of the districts, being

divided into 12 sections, echoing the 12 districts of Panem: access to healthcare, to households, to education, gender equalities, environment, violence … After choosing a cause to defend, fans were then given precise, concrete action plans to follow, which were written by dedicated fans.

(Bourdaa 2016: 100)

Bourdaa is right to say the Capitol.pn campaign focused on the ‘glamour’ of the Capitol rather than the ‘roughness’ of the districts or The Games. But, as the exhibition stressed, this site was meant to be read as initially manifesting the perspective of the Capitol:

The District Heroes and District Voices campaigns in turn highlighted the Capitol’s vision of the districts. They feature noble, hard-working, and loyally patriotic citizens who take pride in the products their homes provide for the good of Panem and who unquestioningly welcome and follow the wisdom and guidance of their leader, President Snow.

(Lionsgate 2017)

The rewriting of the Capitol.pn, as the rebels won and displaced Capitol propaganda with their own, was not as visible as the viral pleasures or antagonisms of the Capitol Couture photoshoots. Similarly, the site’s clear references to fascist iconography, as well the surrealism of couture fashion, often disappeared in the wider circulation of its images.

Lionsgate marketing/merchandising attempted to interpellate fans of the story’s critique of consumption and propagandistic control as well as less self-consciously critical fans. Collins weighed in on the subsequent debate to flag this ambivalence as part of the adaptation:

The stunning image of Katniss in her wedding dress that we use to sell tickets is just the kind of thing the Capitol would use to rev up its audience for the Quarter Quell … That dualistic approach is very much in keeping with the books.

(quoted in Graser 2013)

While meta-fandom sites like The Mary Sue overviewed the best and most innovative Hunger Games merchandise (Polo 2012), offering both positive and negative perspectives, other fans did not always take such self-reflexivity as a sufficient defence. On an advertisement for CoverGirl’s Capitol Collection makeup sets framed as ‘Get Your Bougie Capitol Self Some Hunger Games Makeup’, one fan protested that they ‘didn’t think anything could miss the point worse than Great Gatsby-themed parties or The Help-themed cookware’ (Dries 2013).

One of the most faithful elements of the Hunger Games film adaptations is the way they translate Katniss’s first-person narration into the identificatory figure of movie star Jennifer Lawrence. At the time Film 1 was cast, Lawrence was still a new face, and cinematographic emphasis on her youthful appeal was key to keeping Katniss at the heart of the films even in the most spectacular action sequences. It would be a mistake to discuss the Hunger Games without considering Lawrence’s role in its success.

Studies of stars and fandom have noted the difficulty of converting child or adolescent stardom into adult stardom (O’Connor 2010). Since there have been recognisable youth film genres, young stars have struggled to continue that fame in later years: Mary Pickford, Clara Bow, Shirley Temple, Sandra Dee, Tatum O’Neal, Molly Ringwald, Lindsay Lohan. There are youth cinema stars who continued on to outstanding adult careers, including Mickey Rooney, Johnny Depp, Leonardo DiCaprio, Jake Gyllenhaal, Ron Howard, and Sean Penn. But even where art film and youth drama overlap this more rarely happens for girl-stars, and Lawrence belongs among the obvious exceptions, with Sally Field, Jodie Foster, and Drew Barrymore. Around the time she was cast in the Hunger Games, Lawrence was also cast in Silver Linings Playbook (Russell 2012), for which she won an Academy Award, a Golden Globe, and a Screen Actors Guild award, among others. The director of that film, David O. Russell, has come to represent a crossover point between mainstream and art film success, and so has Lawrence. During the 2011–2012 season in which she won these awards, Lawrence not only featured in Film 1 but in another blockbuster speculative film, X-Men: First Class (Vaughn 2011), as well as other films that continue to be less known. Lawrence was cast for all three star-making films on the back of a relatively small-budget success, Winter’s Bone (2010), written and directed by Debra Granik, where, as in the bigger films, Lawrence plays a young, wily survivor. While filming for the Hunger Games series, Lawrence continued to play more acclaimed roles in dramatic films, like American Hustle (Russell 2013) and Joy (Russell 2015), but Katniss remains a signature role and her most financially successful in box-office terms – although not for her personally, as we will discuss later.

In March 2011, then, when the casting of Katniss was announced, a combination of relative newness and an established fanbase led inevitably to debate. It was by no means clear to fans of Collins’ novels that she was the ideal Katniss Everdeen. One fan response, reprinted from a student newspaper in Huffington Post and then spread across social media, condemned the choice for removing the racial ambiguity of ‘olive-skinned’ Katniss in the novels. Eva Schuler was scathing about the casting call’s brief for Katniss as ‘Caucasian, between ages 15 and 20 … “underfed but strong”, and “naturally pretty underneath her tomboyishness”’ (Schuer 2012). For other fans, she was too old: 21 by the time Film 1 began shooting, while Katniss was 16. However, reception of her potential as Katniss improved over the coming year. Shooting for Film 1 began three months before Silver Linings Playbook (in July 2011), and both followed the shooting of X-Men: First Class in the northern summer of 2010 and premiering around the time Film 1 went into production. While Winter’s Bone had been successful, it was neither a blockbuster nor a family- or youth-oriented film, and Film 1 thus piggybacked on the success of Lawrence’s role as Raven/Mystique in the X-Men franchise, with the advantage that the heavy makeup she wore as Mystique allowed more identification between Lawrence and Katniss. Lawrence’s blockbuster success drew audiences to her more acclaimed dramatic roles far more than it dignified any artistic claims for the Hunger Games films, although her acting was highly praised. Our point is more broadly that the identification of Katniss with Lawrence was, and continues to be, important to the success of the franchise. We cannot subtract from the Hunger Games either Lawrence’s cinematic or extra-cinematic image, including her credibility as a young female actor vocal about additional pressures on young women in the film industry, and representing herself as a feminist.

In October 2015, Lawrence published an essay, ‘Why Do I Make Less than my Male Co-Stars?’, in the feminist newsletter Lenny (co-created by Lena Dunham, creator of HBO’s Girls). Here, she wrote about trying to have creative input as a young female star:

I’m over trying to find the ‘adorable’ way to state my opinion and still be likable! F*ck that. I don’t think I’ve ever worked for a man in charge who spent time contemplating what angle he should use to have his voice heard. It’s just heard.

(Lawrence 2015)

Lawrence never distanced herself from popular roles in the wake of her artistic acclaim, and she did not distance this political stance from the Hunger Games either, crediting it to having lived with Katniss for four years: ‘I don’t see how I couldn’t be inspired by this character. I mean I was so inspired by her when I read the books – it’s the reason I wanted to play her’ (Miller 2015).

In the popular public sphere, as well as in academic scholarship, many feminists see more problems than benefits in such girl-star feminism. Roxane Gay, for example, claims that such voices as Lawrence’s may raise awareness ‘about what [feminism] means and what the movement aims to achieve’, but that a price is paid when it takes ‘a pretty young woman’ to have ‘something to say about feminism’ before ‘that broad ignorance disappears or is set aside because, at last, we have a more tolerable voice proclaiming the very messages feminism has been trying to impart’ (Gay 2014). The Hunger Games has thus become entangled not only with relations between screen girlhood and feminist theory but with debates about celebrity feminism, for which several key voices have been actresses known for girl hero roles, including Emma Watson, who played Hermione in Harry Potter; Kristen Stewart, who played Bella in Twilight; and Maisie Williams, who plays Arya in HBO’s Game of Thrones.

This vein of celebrity feminism has sometimes undermined oppositions between elevated modes of political or artistic discourse and popular culture, as well as critiquing categorical definitions of feminism (see Taylor 2016). Asked about her most recent film at the time of writing, the art production Mother (Aronofsky 2017), Lawrence said:

‘To me, this is incredibly feminist in the way that these Victorian, patriarchal novels show these loving, amazing husbands that are very slowly and delicately taking away their wives’ dignity’ … Lawrence … was reading ‘Jane Eyre’ during the shoot. ‘To be a feminist movie, we don’t have to all be women and all be aggressive. Before we knew what feminism was, people were writing these novels that showed women’s strength being drained from them’

(quoted in Setoodeh 2017)

With this context in mind, the ease with which feminism becomes a test to be failed in the analysis of girl characters like Katniss is continuous with the dismissal of feminism when the speaker fails an implicit test of ideal feminist subjectivity.

Lawrence’s commentary on how she, and other girls and women, might relate to the highly manicured self-images which are her professional stock in trade are also relevant here. It comprises another image of Lawrence, circulating whether she is being dismissed or praised – which is not to deny, reversing Gay’s point earlier, that some price is paid when hostile dismissal of feminist voices is a form of feminist credentialing. In response to praise for her understated version of glamour, Lawrence argued the film industry should seek

a new normal-body type … Everybody says, ‘We love that there is somebody with a normal body!’ And I’m like, ‘I don’t feel like I have a normal body.’ I do Pilates every day. I eat, but I work out a lot more than a normal person. I think we’ve gotten so used to underweight that when you are a normal weight it’s like, ‘Oh, my God, she’s curvy.’ Which is crazy. The bare minimum, just for me, would be to up the ante.

(quoted in Brown 2016)

Our point is not to hold Lawrence up as any resolution of anxious ‘postfeminist’ discourse, or to deny that feminism can be commodified, although whether that undermines its capacity to do any feminist work is another question. Earlier in 2017, Lawrence was photographed in a US$710 t-shirt by Dior, for which she is ‘brand icon’, bearing the slogan ‘we should all be feminists’. This featured on the cover of Harper’s Bazaar and spawned a ‘trend alert’ column on The Fashion Spot website, titled ‘We Should All Be Wearing Feminist Tees’ (Tai 2017). Predictably, this inspired both social media scorn and columns on how to find more affordable versions.

Lawrence’s acclaim as an actor is no more important to the Hunger Games franchise, considered as a whole, than her place as a feminist commentator, including her insistence that her feminism is not disallowed by her evident cultural advantages. This relates directly to the characterisation of Katniss which, while it may be dismissed as trivially girly by writers like Stephen King (see introduction), offers images of leadership and courage. The importance of feminist change is equaled by the importance of acknowledging feminist change. The prevalence of popular girl heroes (even while they still work as a surprise), and the viability of a celebrity prepared to be outspoken about ongoing gender inequalities, both belong to an important historical trajectory in which youth film not only has something to say but offers a litmus test.

Katniss does not offer any solution to the structural inequities of Panem. But, in Guy Debord’s terms, Katniss creates a series of situations that expose the intolerable stratification and authoritarianism of Panem – including the berries, Rue’s grave, and most of all killing Coin – and she facilitates others. She helps, we could argue, make a new map of Panem, which brings us back to the media work as ‘affective map’. For Shaviro, these are maps of how it feels to live in the world, but maps in this sense can be interpreted, used, and mean in many ways. Shaviro credits his conception of ‘map’ to Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari, who claim that ‘What distinguishes the map from the tracing is that it is entirely oriented toward an experimentation in contact with the real’ (1987: 12). The media work as affective map is, then, a speculation – like Snow’s troublesome ‘hope’ and Jameson’s or Dyer’s ‘utopia’. The situations Katniss helps create refer to a reality beyond them that also encompasses Lawrence’s dissatisfaction and uncertainties.

At the end of the Hunger Games, riddled with uncertainty about the future their children will face, Katniss embraces Peeta’s suggestion that at least they can help them ‘understand’ the world ‘in a way that will make them braver’ (Book 3: 456). Speculative fiction can create situations in this sense because, like all fantasies, it is simultaneously impossible and socially determined – real and unreal. For contemporary readers Katniss is, at least in part, an assemblage of fantasies about girlhood, and one in which feminism plays an integral role. The Hunger Games, like speculation in general, is not instructive but aspirational. Katniss raises the possibility, including for fans like Lawrence herself, of refusing the authority and coherence of spectacle – of refusing the idea that, to turn a fannish phrase, resistance is futile. To quote President Snow: ‘If a girl from District Twelve of all places can defy the capitol and walk away unharmed, what is to stop them from doing the same?’ (Book 2: 25)