Civil conflicts are incredibly complex. While there may be similar factors that influence relationships, tactics, strategies, and patterns of violence, each situation is also unique because of the way in which those factors interact. Two conflicts may seem very similar at first glance but end up with entirely different outcomes. As they evolve, unique aspects of the participants, geography, group goals, resources, and relative capacities can result in dramatic changes. These realities make examining patterns of violence problematic. Frequently, the nuances of each case are what matters.

Some intrastate conflicts are enduring in nature. They tend to ebb and flow, involving periods of armed struggle intermixed with times of little to no violence. Efforts to address underlying grievances and bring about conflict termination may occur, but in such cases resolution attempts are frequently unsuccessful, leading some to label them as “intractable” or as enduring rivalries (Kriesberg 1998).1 Other conflicts, however, may be episodic, or short-term affairs involving a brief period of armed struggle that terminates and never reemerges. Intrastate conflicts can vary in intensity as well. Some, although lasting for decades, may involve low-level violence and displacement, whereas others may experience extremely high levels of violence and occur at various times throughout the conflict history or over a short period of time. The intensity of episodic conflicts can vary in similar ways. Further, intrastate conflicts can vary dramatically in terms of the tactics employed by the actors involved. In some cases, innocent bystanders are targeted, sometimes on a massive scale, while in others, guerrilla warfare dominates or negotiations are prevalent. What accounts for these divergent experiences? By taking a closer look at the actions and reactions occurring within intrastate conflicts over time, one can get a better sense of how and under what conditions conflicts unfold and how more enduring rivalries evolve as compared to their more episodic counterparts. This book examines both specific rivalries that have evolved between actors over time and the more general context of the conflicts.

Examining the dynamic interactions of actors engaged in intrastate conflicts is challenging. Nonstate actors tend to be secretive. This may be necessary in order to survive against their typically more powerful opponent. Rebels may exaggerate their numbers or their support in order to achieve legitimacy. Although such actors may have access to weaponry, it is often unclear what the acquisition channels are or the types of weapons they possess until they are used on the battlefield. Governments in the midst of armed conflict also may not be forthcoming with information about their actions. Repressive approaches to dealing with such opposition may be frowned upon by international actors. As a result, it is not always immediately clear what a government has done when it engages with its nonstate opponent. Of course, over time, its actions, along with those of its opponents, typically become a part of the historical record, which is examined in the form of a series of conflict case studies. Although it may not always be clear what exactly transpired, which actors and how many were involved and under what conditions, through the use of historical and archival accounts a general sense of how intrastate conflict actors interacted and the tactics they employed can be developed. Patterns of violence can also be recognized and analyzed to determine what contributed to changes.

Among the most important aspects of civil conflicts are the decision-making processes that occur on both sides about whether to attempt to resolve their differences through peaceful negotiations or to resort to violence, and if one or both sides choose to employ violence, do they also include campaigns of terror? According to Coker (2002), one of the consequences of globalization has been a shift from instrumental violence (between states or communities) to expressive violence (carried out as a form of communication or ritual, or for a symbolic purpose). Factors that contribute to this decision-making process include politics, economics, military considerations, ideologies, and cultures. Another important influence is the role elites and leaders play as compared to that of rank and file members of groups (Cronin 2002/2003).

What follows is a framework that seeks to explain patterns of violence and group dynamics in intrastate conflicts by examining rebel group actions, their tactic selection processes, and the addition or subtraction of additional players. Each of these factors influences and is influenced by the others; the various combinations of factors determine to a large extent the direction any particular conflict will take. This focus is a particularly neglected aspect of conflict dynamics that involves factors related to the rebel group and its conflict with the government. This is not to say that government capabilities, actions, and other characteristics are not important. In fact, they are. But they are presented here as an intertwined relationship of the group, its characteristics, and its capabilities.

Actors engaged in civil conflict make tactical choices in order to achieve their political goals. Their choice in tactic will influence subsequent decisions by conflict opponents as each set of actors makes revised assessments of their position in the conflict relative to their opponent. These actions and reactions are the factors that influence the direction that a conflict will take and how long it will ultimately endure (Olson Lounsbery and Pearson 2009). Tactical decisions and the impact subsequent actions have on the patterns of violence in a conflict are important in understanding their progression. There are a large number of factors that have been identified in the literature that have the potential to influence the tactics of nonstate actors.2 However, these characteristics alone do not provide a sufficient understanding of conflict dynamics. What is necessary is that researchers gain insight into the interaction of the variables as the conflict evolves.

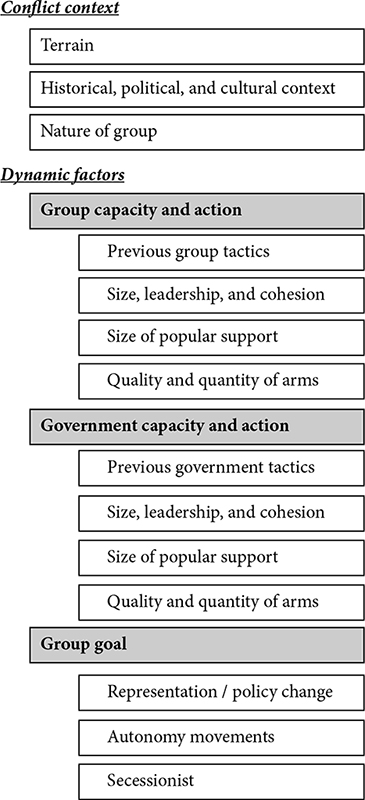

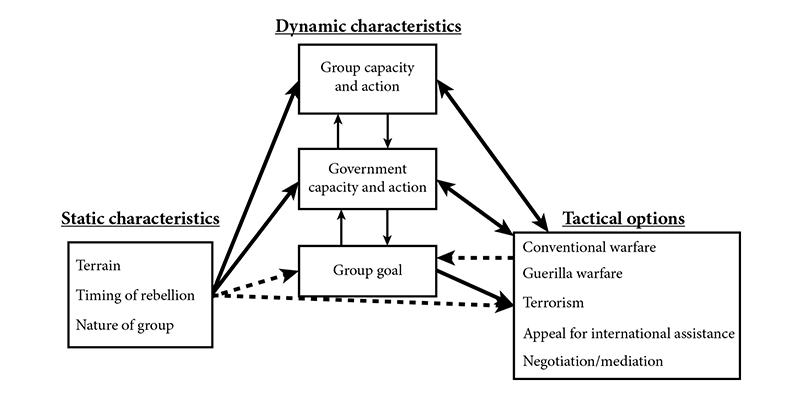

Group and government decisions to employ one set of tactics over another at any point is likely influenced by two sets of factors. The first is thought to be static in nature involving the context of the conflict, while the second set of factors is more dynamic in nature and evolves over time.

Conflict actors are impacted by the environment in which they operate. The characteristics of the conflict environment are primarily static or slow to change. A country’s terrain, for instance, is unlikely to experience significant alteration due to ongoing strife but would likely influence tactical decisions made by rebels and government actors as each pursues their goals. Available mountainous or jungle terrain may allow insurgents to evade governmental pursuit more effectively than those operating in urban settings, for example (Fearon and Laitin 2003). Conflict occurring with such terrain advantages would be expected to endure longer than others.

Conflicts and rivalries unfold in the context of the nation’s political, social, and cultural history as well. Factors such as colonial legacies (Henderson and Singer 2002) and group identity hierarchies (Gurr 1993) lay the foundation for the types of conflicts that may emerge, but they also are likely to influence tactical choices, and therefore conflict progression. A conflict that emerges out of a history of unfair treatment during a country’s colonial history, which itself becomes embedded in the nation’s culture, may make the targeting of civilians, particularly of opposing identities, more acceptable than those emerging under a different historical and cultural context, for example.

A third static factor of the conflict environment thought to influence tactical decisions has to do with the nature of the group itself. Groups that tend to be defined by their ethnic, religious, or cultural identity have a tendency toward more secessionist goals (see Gurr 1993), whereas ideological groups are typically more focused on regime change or political revolution (see Licklider 1995 and Regan 2000a for further discussion of this conflict dichotomy). Groups, and therefore rivals, that define themselves in ethnic, religious, or cultural terms that they view are different than the identity of their government may also find terrorist tactics more acceptable than ideological groups that wish to change the nature of the political regime but do not necessarily see themselves as a distinct identity relative to the rest of the population. As a result, the nature of the group engaged in the conflict will likely influence what sorts of tactics will be acceptable in order to achieve conflict goals.

Although conflict progression may be influenced by these static factors, the action-reaction sequences that unfold over time are dynamic in nature. Understanding the changing environment that influences tactical decisions is the next topic for discussion.

In contrast to the static variables, those that are dynamic are more likely to shift over the course of the conflicts in reaction to other factors. Each set of actors engaged in a conflict may be affected by the actions of the others or by societal reactions. These variables influence the future decisions and actions of both nonstate actors and their government. They are expected to behave similarly regardless of which takes action.

The tactics that each actor employs will likely have an impact on the selection of tactics by others involved. Today’s actions can be expected to influence tomorrow’s decision making and subsequent actions taken. Government repression, for instance, may result in increased support for a nonstate group, or it could cause an opponent to engage in more violent actions. In fact, some groups may engage in violence in the hopes of driving their government to become increasingly repressive (Bueno de Mesquita and Dickson 2007; Bueno de Mesquita 2005).3 This could increase the support for nonstate actors both domestically and internationally, as these communities unite in rejection of the government’s use of violence. This demonstrates that groups and governments understand that their actions will provoke reactions from the other and emphasizes the importance of studying the dynamic interactions of the combatants. Tactical decisions, and therefore conflict progression, are thought to be influenced by the relative nature of group and government capacity, as well as group goals.

Group size, its leadership, and its cohesion are determinants of capacity. When one actor in a conflict has a significant numerical disadvantage, it may feel compelled to resort to nontraditional tactics (terrorism or guerilla warfare) in order to cope with the asymmetry (Olson Lounsbery and Pearson 2009). An increasing disadvantage with respect to size may also drive a group toward increasing levels of violence. As the size of a group or number of government troops devoted to a conflict increases, one would expect the engagements to move away from terrorism and toward other tactics. One of government’s advantages in intrastate conflict is that it not only usually enjoys a numerical advantage in the number of troops but also often has the ability to determine the proportion of its troops that it will commit at any given time. Governments may therefore have a surge capacity that is not enjoyed by the nonstate combatants. Confidence emerging from the size of one’s group relative to its opponent is likely to deter that group from engaging in good faith negotiations, choosing instead to pursue uncompromising military victory. Leadership and cohesion are also important factors and are discussed in greater detail below.

FIGURE 1.1 Characteristics of Tactical Choice

As indicated, civil war and rivalry research tends to view rebel groups, as well as their opposing governments, as both static and singular. Simplifying conflict to a set of bilateral interactions helps with systematic analysis but does little to capture the realities of the relationships. As conflicts evolve, participants may be altered in a number of different ways. One of the more common intragroup changes in the midst of civil war involves group cohesiveness. What may have originally started as a bilateral set of interactions between the government and one rebel group may become multilateral, involving several groups. Governments may experience internal divisions as well. For the most part, governments are more likely to present a united front toward rebellion, but members within the government may disagree over the approach or on issues unrelated to the rebellion. Segments of the government’s military could potentially revolt and join the rebellion. Internal divisions tend to weaken all parties, and divided governments are no different.

There are many different issues that could lead to a division among rebels. Cunningham (2006) argues that there are three reasons for splinters to form: differing policy preferences, leadership disputes, or disagreements within the group over the strategy to pursue. It is suggested here that policy preferences may involve differences over group goals. Leadership disputes may emerge simply because of clashing egos or serious differences of opinion over how best to pursue group goals, or what those goals ought to be. Leadership differences may also emerge over group strategy.

One might also expect that success, or lack thereof, on the battlefield might bring to light differences within groups. If a group is doing well in its military campaign, there is probably less of a chance that disagreements over policy or strategy will occur. Potential leadership rivals are also likely to be held at bay. When, however, battlefield losses accumulate or earlier successes cannot be repeated, members may begin to reevaluate leadership, strategy, or policy (i.e., group goals), thus creating conditions conducive to splintering. Battlefield losses and a general lack of success in a military campaign tend to force groups and governments to reassess a military approach (i.e., policy preferences or choice of strategy). In such situations, negotiations are possible, which can have significant implications for intragroup cohesiveness.

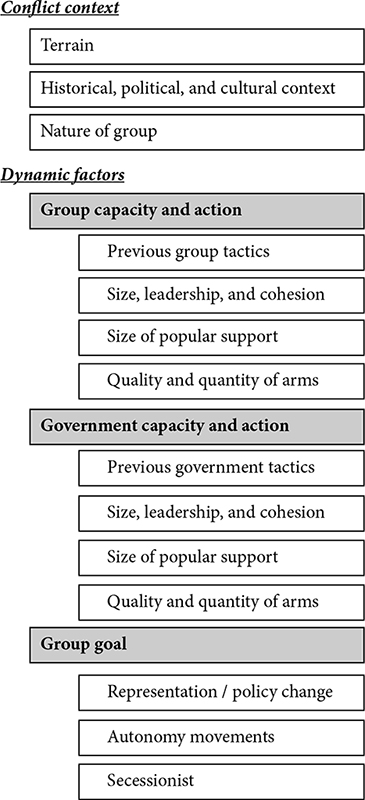

It seems counterintuitive that attempts to negotiate a peace could contribute to escalation of violence and the splintering of groups. The fact is, however, that negotiated settlements rarely result in lasting peace. As Licklider’s (1995) study demonstrated, while military victory tends to be a relatively stable outcome for civil conflict (regardless of the desirability of such an outcome), less than 13 per cent of negotiated settlements were able to sustain peace after five years. Part of the reason for this may be that one side or the other enters into the negotiations in bad faith. They may be bowing to international pressure to engage in the negotiations or trying to gain some strategic advantage through participation. However, they may have no intention of following through on whatever agreement is struck. One might expect such a scenario when one group appears to be losing the military struggle and another winning.

FIGURE 1.2 Negotiation Processes Cause Factions within a Group to Splinter

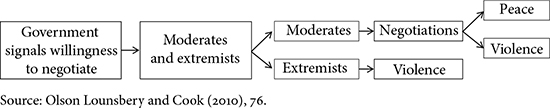

A contributing factor could also be that groups and governments are not unitary actors, as has been indicated. Both sides tend to involve a range of members, from those who can be considered more moderate to those who are more extreme, each of which will have its own motivations to negotiate or not. When they splinter, a more moderate faction is likely to emerge along with a more extreme faction. Multiple splinters will similarly result in a range of factions from moderate to extreme (Bueno de Mesquita and Dickson 2007). Even if the leaders on each side engage in negotiations in good faith and have every intention of honoring the agreement, their followers or other elites could disagree with the settlement or the negotiation process. “Despite the successful negotiated outcomes that can result between major parties, a common effect of political processes is the splintering of groups into factions that support the negotiations (or their outcome) and those that do not” (Cronin 2006, 25). This dynamic is captured in Figures 1.2 and 1.3. If the leadership of either side lacks the capacity to enforce the agreement among their own members, violence can reemerge.

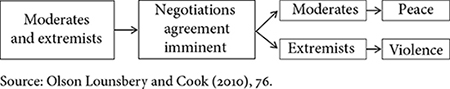

Of course, splintering may occur before negotiations emerge. Such splintering is still going to produce more and less extreme factions. This can work to the government’s advantage. If the government seeks to come to terms with the moderate faction(s) (i.e., negotiate), it can potentially isolate the more extreme members by co-opting selected group members. In diminished numbers, extremist factions could potentially be defeated more easily. By negotiating with one faction, that relationship de-escalates, while at the same time the government is likely to escalate its campaign against the more extreme group or groups (Driscoll 2012). Splintering, in turn, can lead to increased violence in one conflict dyad as the extremists who objected to the negotiations vow to continue the fight, and a de-escalation in another if an agreement is reached with more moderate factions. This divide-and-rule dynamic is depicted in Figure 1.3. The increased intensity on the negotiation-resistant dyad could potentially be short lived, however. The capacity of the splinter faction will be significantly diminished. In order to survive, a shift in tactics may be necessary.

FIGURE 1.3 Government Uses Negotiations with the Intention of Splintering a Group

When a civil war government indicates its willingness to engage in negotiations to end a conflict, the possibility of groups emerging that wish to “spoil” negotiations becomes problematic. “Peace creates spoilers because it is rare in civil wars for all leaders and factions to see peace as beneficial. Even if all parties come to value peace, they rarely do so simultaneously, and they often strongly disagree over the terms of an acceptable peace” (Stedman 1997, 7). A spoiler can be either a party to the conflict or external to the process. A spoiler will always be an actor who does not find peace to be in his or her interest. In some cases, the existence of a portion of the group could be threatened by the conflict’s termination (Bueno de Mesquita 2005). If individuals have based their identities on group membership, settlement may be an unbearable threat. As a result, splinter factions tend to prolong civil wars (Cunningham, Gleditsch, and Salehyan 2009; Driscoll 2012).

In addition to the presence of a spoiler, there are other factors that may have an impact on group splintering. Previous research has demonstrated that there are specific conflict characteristics that statistical analysis shows predispose groups to splintering (Olson Lounsbery and Cook 2010). Group splintering may be more likely early or late in the conflict as compared to the times in between. Early on the group has yet to establish strong leadership and group cohesion. Later in the conflict fatigue and disagreements may be more likely, and groups tend to be more likely to engage in negotiations (Cronin 2010). The intensity of the violence, as measured in casualties, also tends to increase the likelihood of splintering. The size of a group may also influence splintering. As the size of the group increases, the likelihood of splintering decreases. It is also more likely that splintering will occur when the conflict is over territory rather than over ethnicity.

Clearly, group divisions complicate the conflict process and have significant implications for patterns of violence. Divisions within the government may escalate conflict, but when rebels splinter, the implications for government action are more complex. If the government is doing well in its military campaign (or perceives it is doing well), it is unlikely to change its course of action. If there is doubt, however, as to the ability to succeed fully, the government may choose to de-escalate with a more moderate group while escalating with another.

It should be clear at this point that when rebel groups decide to part ways, for whatever reason, their ability to wage war against a typically stronger government is diminished. Their resources are fragmented, and the government may use those divisions against one another. This recognition may result in coalition forming among rebel groups. What is known about rebel group coalitions is somewhat limited and can be considered a neglected area of research.4 One can, however, speculate that coalitions emerge because larger groups are more likely to achieve success on the battlefield. If members can overcome their differences and present a united front, they stand a better chance of winning. The decision to unite or reunite is a rational decision, as a result, because groups want to maximize their utility (Bottom et al. 2000). Creation of a rebel group coalition requires, however, that more moderate and more extreme members compromise on group goals, strategy, or leadership, or perhaps on all three. Players will in essence be forced to give up their preferences that may have led to the splintering in the first place. Riker (1962), in his work on political coalitions, has referred to this as “shaving the quota.” Because coalition forming requires shaving the quota, coalitions are likely to emerge when groups are failing on the battlefield. They may also be viewed as tenuous peace agreements.

Rebel group and governmental leadership are central to this discussion as well. Charismatic leaders who have the ability to persuade and woo followers can dramatically increase a group or government’s capacity. Boulding (1989) has described this type of power as integrative. It costs less than leaders who have to employ threats or inducements to gain membership or following. Rivalries and the groups involved that include charismatic leadership can sometimes become heavily dependent on that integrative power and the personality involved. When that leader is arrested, killed, or otherwise deposed (sometimes referred to as decapitation of the group), those movements or governments may collapse. Further, where leadership personality plays a central role in defining a rival, efforts to collaborate across conflict actors may be challenged by the egos involved.

As indicated earlier, civil wars are particularly complex because states may actually be engaged against multiple rebellions at once. All of these rebellions will share a common enemy (i.e., the government). As a result, it is possible that coalitions may be formed not just within any one conflict among rebels with a shared identity, but coalitions may also be formed across conflicts. By uniting two or more rebel factions across conflicts, rebels enjoy larger numbers, shared resources, and potentially a greater chance of success. These types of coalitions are significantly challenged if there are divergent goals, leadership, and strategy. But they do, nonetheless, occur. Regardless of whether rebel coalitions form across conflicts or within one (i.e., between factions), rebels who emerge as a united front, creating one entity with increased capacity, will typically do so with the hopes of escalating the conflict in pursuit of a rebel victory. It should be noted, however, that even without coalition building the presence of multiple rebellions in a state dilutes a government’s capacity to respond to any one conflict, as it must divide its resources against multiple rivals.

Popular support is another important resource for civil war actors. Both the government and groups benefit from increasing levels of public support for their side. Supported groups can see their capacity increase as recruiting and fundraising are facilitated and safe houses and other assistance are provided. More important, a group that experiences high levels of public support would have less impetus to resort to terrorism, as attacks on civilians would likely be counterproductive, unless the civilians are seen as complicit with the government’s actions. Further, rebels with significant support may be able to use that support as leverage at the negotiating table, making nonviolent approaches more likely. If public support for the group was never experienced or decreased significantly, it could increase the group’s willingness to resort to terrorism. The same arguments apply to governments engaged in conflict. During periods of high support they will find more public compliance with taxation, laws, and calls for the draft, for instance. Attacks on the public under these conditions would likely undermine a government’s goals.

Quality and quantity of arms will also have an impact on tactical decision making. Access to superior firepower has an obvious impact on the capacity of combatants. As such access decreases, more aggressive tactics may be employed in attempts to offset perceived or real military inferiority. This is related to popular support in that groups with high levels of support may have additional funds to purchase more or better weaponry. Increasing parity in weapons between combatants would favor traditional military maneuvers or guerilla warfare rather than terrorism (Sislin and Pearson 2001). In some cases in identity-based conflicts, groups can augment their support by fundraising within their diaspora community (i.e., people of the same kinship group who have fled, often because of fighting, and now live abroad). Of course, armaments are expensive and are easily depleted in battle. As a result, the ability of a group or its government to fund its campaign is important. The government has a clear advantage in this regard as it can typically tax its population and utilize wealth produced by the state to buy weaponry through legal channels (barring any weapons embargo that may be put in place). Rebels rarely have this resource building capacity and tend to fund their endeavors in several ways. They may look to outside assistance (discussed in depth later in this chapter), they may acquire their weapons through theft or success on the battlefield (Pearson et al. 1998), or they may capture resources such as diamond mines or oil fields.

Finally, group goals are treated as dynamic in this study. Although group goals can be multiple in nature and complex, three primary goals have been identified. The first goal is representation, policy, or regime change. Groups may engage against the government in attempts to have their interests included more fully in the policy process or to change the nature of the system itself. Groups with such goals are unlikely to engage in terrorism. Their goals are to get more participation in the existing regime, not to eliminate it. Violence in such a case would likely be counterproductive. The second and third goals are often referred to as self-determination movements. These are the most common forms of violent political conflict within states (Marshall and Gurr 2003). Autonomy movements may seek greater self-rule but are attempting to achieve this within the existing governing system. Secessionist campaigns have the greatest chance to result in violence against civilians, as their goal is to remove themselves from the existing system entirely. Seceding groups are no longer bound by societal norms or the desire to remain within the state system. Goals can change during the course of conflict. It may be that frustration leads a group to progress from demands for policy change to seeking secession as their calls for change are unheeded by government. However, it could also be the case that a group’s goals begin with autonomy or secession.

Collier and Hoeffler (1998) have suggested that rebels are frequently motivated more by greed than by grievance issues. Rebels may be more interested in capturing state resources than any true reform. In such campaigns, greed goals are rarely stated as such. Instead actors tend to couch their movements in the more altruistic goals identified above. If greed is an underlying motive of leadership, however, it should be expected that tactical decisions will be influenced by that reality. Terrorism may be more likely, but so too may negotiated outcomes. Resources are more easily negotiated than goals that are more closely tied to group identity (Rothman and Olson 2001). Rebel leaders may be willing to come to terms with revenue sharing of a diamond mine, for example.

As was previously stated, no one variable discussed above provides an adequate explanation for strategic and tactical decisions during conflicts. Only by understanding the dynamic interaction among these variables can one hope to gain insight into why groups and governments behave as they do. It is only recently that scholars have started to study the dynamic aspects of civil wars (see the work of Olson Lounsbery 2005; DeRouen, Bercovitch, and Wei 2009; Olson Lounsbery and Pearson 2009). Figure 1.4 presents an interaction framework that illustrates the process that leads to ebbs and flows in political violence.

FIGURE 1.4 Tactical Choice Interaction Framework

In addition to the static and dynamic variables, the figure also lists potential tactical options that are available to the combatants. In the text above, factors that may cause rebels to turn toward or away from terrorism were discussed. Those are examples of this kind of shift in tactics in response to dynamic interactions. In this section, the focus is on tactical options and what might influence their selection.

Rebels engaged in an intrastate conflict with government have already made the decision to take up arms and engage in armed conflict. Once that armed conflict ensues, groups reconsider their approach in light of both performance on the battlefield and the behavior of their opponent. Armed insurrection can take three different forms: conventional warfare, guerrilla warfare, or terrorism. These tactical decisions are not mutually exclusive. Conventional warfare is distinguished from guerrilla warfare by the way in which nonstate actors engage with the government. Guerrilla warfare by definition involves hit-and-run tactics allowing rebels to engage briefly with the government followed by a retreat to a safer place. Conventional approaches to armed conflict involve more sustained combat.

One of the challenges in studying this phenomenon is making the distinction between terrorism and other forms of political violence. It is particularly difficult to differentiate between guerrilla warfare and terrorism, as both are asymmetric warfare strategies employed by the disadvantaged combatant.5 There are a huge number of potential definitions of terrorism from which one could draw. Even before 9/11 brought the issue into the mainstream, Bruce Hoffman identified 109 separate definitions for terrorism in the scholarly literature (Hoffman 1998, 35–40). A common distinguishing characteristic among the definitions is the targeting of civilians or so-called innocents (see, for example, Feldmann and Perala 2004, 104). This raises the question of what combatant characteristics and conflict dynamics may push a group to identify citizens as legitimate targets for violence.

Given the Global War on Terrorism and its prominence as an issue in international relations, this is something that must be better understood. Attacks against civilians may be conceptualized as the most extreme manifestation of political violence. Both groups and governments may target civilians during the course of conflict. On occasion, civilians are targeted because of their perceived support for one side in the conflict. At other times, violence may become completely indiscriminant. Rebel groups and governments in the conflict may decide to engage in violence against civilians.

At the onset of strife it can be assumed that the government will enjoy many strategic advantages over the rebel group. A potential disadvantage for the government, however, may be an inability to distinguish civilians from combatants, who by definition will be unlikely to wear a uniform or insignia. This can lead to confusion about what a government’s intentions were when attacks killed civilians. The ability of a group to choose one tactic over the other is a function of its capacity vis-à-vis the government, terrain, and group goals. All are thought to escalate a conflict and contribute to more enduring violence should such tactics prove successful.

As the conflict progresses, armed or violent tactical options may be replaced by a desire or a need to negotiate a resolution, particularly if other approaches are failing. Negotiations involve unassisted efforts by rebels to engage in a dialogue with the government over issues of the conflict aimed at resolution, or at least conflict de-escalation. Due to the typically asymmetric nature of intrastate conflict, unassisted negotiations do not occur as frequently as third-party assisted, or mediated, attempts. This is not to say that negotiations do not occur in intrastate rivalries, but when they do occur, they rarely address underlying grievance issues of the rivalries (Olson Lounsbery and Cook 2010). In order to get parties to come to the negotiating table in good faith and address core conflict issues, third-party influence is frequently necessary.

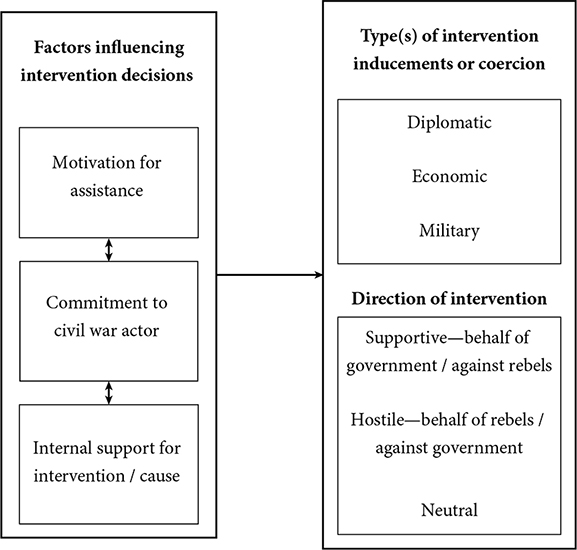

Intrastate rivalries, despite the fact that they tend to be “internal” struggles, tend to draw attention from the outside world. Further, civil wars and rivalries are generally contagious (Forsberg 2009). Violence, whether on purpose or unintended, draws attention from other states and the international community. In fact, intervention into civil wars is a frequent occurrence (Regan 2000a). External actors, whether nation-states or intergovernmental organizations, become involved in civil wars by offering financial aid or threatening sanctions (economic intervention), troops or military aid (military intervention), or third-party assisted mediation (diplomatic intervention). According to Pearson and Baumann (1993), interventions vary depending on the direction of intervention. External actors may be motivated to support an ally government, but they might also choose to intervene in support of the rebellion. Not all interventions are as specifically targeted, however. Some may be designed to be neutral in nature, with the goal of stopping the fighting. Civil wars may also involve intervention in the form of cross-border raids as neighboring countries find themselves impacted by fleeing refugees or rebels. The impact of the internationalization of civil wars is well explored, but its relationship to tactical decisions and conflict patterns is complicated by several factors. Some of these factors relate to interactions already discussed, while others emerge as new complicating processes. In order to understand the intervention-conflict progression relationship better, one must recognize that all interventions are not alike. What motivates intervention will impact its type (diplomatic, economic, military) and direction (at whom the intervention is targeted), which will then determine, along with other factors, how it influences patterns of violence.

Figures 1.2 and 1.3 demonstrate what the impact of diplomatic intervention may be on the subnational actor engaged in conflict. Figure 1.4 suggests the factors that would motivate a civil war actor to seek outside assistance. Figure 1.5 depicts the decision-making dynamics of the international intervener, which is another significant piece of the puzzle. The motivation for such assistance may or may not be a request made by a civil war actor. The appeal for international assistance in the group tactic options box in Figure 1.4 captures this type of request. This is not to say that an international actor would not decide to intervene without receiving a request from the government or rebels, but the focus here is on understanding why groups or relevant governments would choose to make such a request as a tactical decision.

By definition, civil wars occur within the borders of a recognized nation-state with one of the warring parties being the government of that state (Small and Singer 1982; Gleditsch et al. 2002). As a result, international legal norms that value state sovereignty would suggest that civil war states would naturally be hesitant to request or allow an intrusion into their own affairs. As mentioned previously, for the most part at the onset of a conflict, civil war governments enjoy a preponderance of power (Bapat 2005). Under these conditions, a government is unlikely to request external assistance in any form because such action may convey weakness and potentially challenge the validity of that government’s sovereignty. At the onset, a government facing internal armed challengers would typically attempt to use this initial advantage to deal with the opposition swiftly. It is fairly unlikely at this stage that a civil war government will view external intervention, in any form, as either necessary or beneficial.

FIGURE 1.5 International Intervention Dynamics

Should the armed conflict continue despite initial attempts by the government to alleviate the threat, however, requests for external assistance become more likely. Bapat (2005) has suggested that civil war governments are most likely to request assistance once it becomes clear that their military efforts alone are not bringing about a swift enough end to the insurrection. If requests for military intervention on behalf of a civil war government are granted, this will likely signal an escalation of the conflict as the government ratchets up its efforts to defeat the rebels. Governments are unlikely to request diplomatic assistance (which could potentially lead to a mediated settlement) at this time, as it would be inconsistent with the goal of defeating their opponents militarily. Economic interventions allow civil war governments to address potential grievances, thereby undermining support for armed factions that may have used such grievances as a rallying cry. Under these conditions, one would expect that economic intervention would also signal an initial escalation of conflict followed by de-escalation if the rebel support base becomes undermined. If, however, military or economic intervention assistance does not achieve the desired military victory for the government, requests by the civil war government for diplomatic intervention in the form of third-party-assisted negotiations become more likely. This phase, when it involves the failure to produce a military victory, can be characterized in many situations as a mutually hurting stalemate that is ripe for resolution (Zartman 1989; Zartman and Touval 1985). The fear of further loss and the fatigue of fighting can lead actors to reevaluate and reconsider their commitment to violence (Zartman 1993; Fison and Werner 2002; Powell 2004; Slantchev 2003). Fighting is expensive, and costs accumulate over time. Actors tend to look for alternatives to fighting when victory remains elusive and costs continue to be incurred (Greig 2001; Zartman 2000). Diplomatic intervention then becomes an alternative worthy of consideration.

It is not the case that all such calls for mediation involve a mutually hurting stalemate, however. If a civil war government makes requests for military or economic assistance, but those fall on deaf ears, are not reciprocated to the extent necessary to win the war, or simply do not produce the desired result, a situation can arise where the rebel group faction(s) move closer to achieving military victory. A civil war government, facing defeat, may seek external diplomatic assistance for the purpose of negotiating an exit to the conflict or a safe departure from the country. Whether negotiations are being sought to end a stalemated war or to complete a victory, the expectation is that, if successful, de-escalation becomes very likely. If requests fall on deaf ears, however, a failed negotiation may result in the escalation of violence. If intervention is too limited to assure victory, de-escalation is likely regardless of the outcome of the talks. Military victory will bring about resolution regardless of whether the former leaders find their own safe haven or are able to negotiate a role in the postwar government.

Relative to their governments, rebels are more inclined to seek external assistance early in the conflict, albeit for similar reasons. Although the international legal norm valuing sovereignty would suggest that most interventions will occur on behalf of the civil war government and with its consent, in practice this is not always the case. When such interventions do occur on behalf of rebels, their situation tends to be improved regardless of intervention type. Given the asymmetric power relationship, and the already perceived legitimacy of the civil war government, rebels are at a distinct disadvantage early in the conflict. When external actors decide to intervene on their behalf, the nonstate actor’s cause can gain legitimacy.

For rebels, diplomatic intervention may occur in some important ways. First and foremost, as conflict unfolds and violence ensues, external actors may call for talks. While those calls may be unheeded by warring governments for reasons mentioned above, the suggestion of such discussions serves as recognition that assistance is needed. Should talks emerge where the mediator advocates on the nonstate actor’s behalf, rebels are more likely to elicit peace agreements, and the provisions of such agreements are likely to be more meaningful, such as power sharing (Olson Lounsbery and DeRouen 2015; Svensson 2009). As conflict continues, however, if rebels have had negative experiences in negotiations, their preference for diplomatic assistance may wane. Further, if they are able to receive material forms of intervention, which actually work to bolster their capabilities, a diplomatic solution may no longer seem to serve their needs.

Economic intervention on behalf of rebels can also improve their chances. Engaging in armed struggles requires weaponry, which rebels typically lack as compared to their governmental opponent, especially early in the conflict. Even over time, however, rebels will need to replace spent weapons or to arm additional recruits. As a result, absent some other form of revenues, rebels frequently look to outsiders for assistance (whether it be economic aid, training, or actual foreign military intervention on their behalf). An influx of such resources can allow groups to continue the fight or escalate a conflict in significant ways.

The most expensive form of intervention from the perspective of the intervener is foreign military intervention. When it is forthcoming, however, the power hierarchy of the conflict can be changed dramatically, increasing the chances for rebel victory (Balch-Lindsay, Enterline, and Joyce 2008). Given the asymmetric nature of most civil wars, it is not uncommon for rebels to seek such assistance. Of course, doing so means that rebels will lose some of their autonomy and decision-making ability. This was the case with the Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA) when NATO engaged with Serbia on their behalf. The KLA was forced to accept what they perceived as unacceptable terms or face complete withdrawal of support (PBS 1999). The desire to maintain their autonomy may deter rebels from seeking foreign military intervention, though they are more likely to accept such assistance than the opposing government.

Actors engaged in intrastate conflict make tactical decisions repeatedly over time. Many issues factor into each decision, including their capacity vis-à-vis their opponent, prior successes and failures, and goals. At various times in a conflict or rivalry rebels and governments may choose to employ violent approaches (i.e., conventional warfare, guerrilla tactics, or terrorism), seek outside assistance, or make appeals for dialogue. These tactics could be cycled through sequentially or could be entered into at any point. In fact, groups and governments are likely employing more than one tactic at a time.

Static factors may have an influence on each aspect of the dynamic conflict but will not be altered by them. Static factors may also have some impact on group goals and the choice of tactic, by bracketing the range of possible responses. It would be unlikely that any of the static characteristics would be a determining factor for a group’s goals. Tactic selection is clearly a very dynamic process. The tactic being pursued by each side is heavily impacted by the conflict dynamics identified in this chapter as well as by the other side’s previous actions, providing a feedback decision-making loop. Groups and government may pursue the same tactics over a long period of time, or their behaviors could change in reaction to some event. Tactical decisions influence escalation and de-escalation and determine the strategies that are adopted by not only combatants on both sides but by international actors as well.

To evaluate the theoretical framework presented here, conflict chronologies were created using the New York Times, Keesing’s World News Archive,6 and published interviews with key actors, scholarly research, and reports on each of the six countries and the conflicts occurring within them. Chronologies were comprehensive in nature capturing events, such as battles/attacks, negotiations, interventions, and group dynamics, but also discussions of group and government capacity, such as troop levels or territory captured. Through the use of chronologies, not only could group and government tactics be identified, but the conflict environment and the context under which tactical decisions were made, such as engaging in negotiations or shifts toward targeting civilians, could be better examined. What follows is the application of the theoretical framework presented on each of the countries examined here. The variables identified in the frameworks are drawn from the case chronologies.