Sri Lanka’s civil conflict has been characterized by continued waves of violence. The country’s Sinhala and Tamil populations have vied for governing power since independence. By 1983, the situation erupted into civil war, with the Tamils fighting for an independent homeland in the northern and eastern regions of the country. The violence escalated and de-escalated through more than twenty-five years of conflict, with lulls in violence resulting in the civil war’s classification into four distinct periods, Eelam Wars I–IV. Fighting peaked in 2008–2009 with over eight thousand casualties per year, as the sides fought to the military defeat of the dominant Tamil rebel group, the Tamil Tigers (UCDP). This case is unique, as compared to the others in this book, because it is a single protracted rivalry and because the Tamil Tigers were an innovative terrorist organization.

Sri Lanka is an island in the Indian Ocean off the southern tip of India. The geography of the country consists of largely low, flat rolling plains, with some mountainous terrain in the south and central regions. The fact that it is an island, sharing no borders with neighboring countries, likely limited the amount of intervention in the country’s civil wars, aside from that of India, whose own Tamil population incentivized intervention. Tactics on both sides tended to focus on trapping the other side with their backs to the sea. The rebel groups engaged largely in guerrilla tactics, as well as terrorism, as they did strike civilian targets.

The conflict in Sri Lanka is rooted in British colonial rule. The British, using their common divide-and-rule practices, favored the minority Tamils versus the Sinhala majority, resulting in their disproportionate representation in universities and in employment in government and business at the time of independence. Some Sinhalese also perceived the Tamils as being collaborators with the imperialist British rule (Bhattacharji 2009). Singer (1992) cited arguments that the north and east of the country, where the Tamils have traditionally been concentrated, had so little agriculture or industry that the Tamils had to become better educated and enter these types of employment as there were no other options. It is likely that neither the British colonial powers nor those who ruled Sri Lanka upon its independence understood the extent or complexity of the societal fragmentation of the country (Little 1994). The Sinhala, having achieved majority rule upon independence, reacted to this perceived disproportionate representation of the Tamils aggressively. Tamils were denied citizenship and the right to vote. The Official Language Act of 1956 declared Sinhalese to be the official language of the country. In 1963, university admissions policies were changed to give significant preference to Sinhalese applicants (Raman 2009). This was followed in 1971 by a revision of the university system that drove Tamils out of university teaching and research positions (Nieto 2008, 576–577). In addition, “from 1956 to 1970 the proportion of Tamils employed by the state fell from 60% to 10% in civilian employment and from 40% to 1% in the armed forces” (577). The new constitution of 1972 went so far as to eliminate minority protections that were included in the 1947 constitution (Hopgood 2005). These actions served to demoralize and disenfranchise the Tamil population of the country, as well as leaving them geographically isolated and concentrated. The situation was so egregious as to have caused Hopgood (2005) to comment that “for nearly six decades, since the former British colony of Ceylon secured its independence in 1948, the Tamils have experienced systematic and unrelenting discrimination from the majority Sinhalese population in Sri Lanka” (43). According to DeVotta (2000), in addition to these problems, the Tamils perceived that government resources were unfairly allocated. This included Sinhala resettlement policies (discussed later in the chapter) and the unfair allocation of international aid given to stimulate development or even funds designated to foster recovery from the 2004 Asian tsunami.

In addition to these factors, the Sri Lankan Tamils objected to a resettlement campaign that was undertaken by the government, which resulted in the movement of largely Sinhala citizens from the south and west into the traditional Tamil areas of the country. The Tamils saw this as a form of colonization of their homeland. The Tamils felt that the programs were put into place with the purpose of diluting their concentration in historically Tamil-occupied regions. This would have the effect of diminishing Tamil impact on elections and undermining their persistent claim that their territorial concentration was justification for autonomy or independence (DeVotta 2000).

The Sri Lankan situation is dominated by one major rivalry, that of the Sinhala versus the Tamils. There were actually a number of different Tamil groups who claimed to represent the interests of the Tamil minority population. However, none approached the persistent power versus government that the Tamil Tigers did. In part, this can be attributed to the Tigers’ tendency to work to defeat rival Tamils.

TABLE 4.1 Timeline of Key Events in Sri Lanka’s Conflicts, 1956–2012

Date | Event |

1956* | Sinhalese designated official language of Sri Lanka |

1972* | New constitution seen by Tamils as giving Sinhalese permanent social and political dominance |

1976* | Liberation Tigers of Tamil Elam (LTTE) got its name and began low-level campaign |

July 23, 1983* | Killing of 13 SLA soldiers by an LTTE landmine led to a backlash of anti-Tamil violence and beginning of the Sri Lankan civil war |

August 1984* | LTTE declared full-scale revolution |

May 1985* | By this time LTTE controlled Jaffna City and much of the peninsula, formed a temporary alliance with other pro-independence Tamil groups |

May 1986* | Sri Lankan Army (SLA) offensive |

September 1987* | Indian Peacekeeping Force (IPKF) arrived, was quickly drawn into conflict with the LTTE, and suffered significant losses |

September 1989* | IPKF declared ceasefire with LTTE |

March 1990* | IPKF withdrawn from Sri Lanka |

June 19, 1990 | LTTE reportedly used a chemical agent against Sri Lankan Armed Forces installation, the first known chemical attack by a guerrilla or terrorist organization (Hoffman 2009) |

March 1991* | LTTE assassination of Defense Minister Ranjan Wijerante |

May 1991† | Assassination of Indian president Rajiv Gandhi by the LTTE |

May 1993† | Assassination of Sri Lankan president Ranasinghe Premadasa; LTTE denied responsibility |

November 1994* | Chandrika Kumaratunga elected president of Sri Lanka. Promised talks with LTTE, loosened economic restrictions on LTTE-held areas, and arranged a ceasefire. |

April 1995* | After many breaches, a truce and talks broke down |

January 31, 1996* | LTTE suicide bombing killed 80 in Colombo |

July 1999† | Assassination of Sri Lankan member of Parliament Neelan Thiruchelvam, a Tamil who was working on a peace initiative with the government |

1999* | Fighting escalated, with the advantage shifting between the LTTE and government troops throughout the year |

December 1999† | Two suicide bombings in Colombo by the LTTE, one of which injured President Chandrika Kumaratunga; 21 died in the attacks |

2000* | Norway engaged in mediation |

April 2000* | Months of fighting resulted in LTTE capture of the Elephant Pass, the largest defeat of the SLA in the war. LTTE operated as a conventional army rather than using guerrilla attacks. |

June 2000† | LTTE assassination of Industry Minister C. V. Goonaratne |

April 2001* | LTTE ended ceasefire, and SLA mounted a failed offensive in Jaffna |

2002* | Indefinite ceasefire signed by both sides; Sri Lankan Monitoring Mission (SLMM) created to maintain the peace |

2003* | LTTE pulled out of peace talks after six rounds, but ceasefire held |

2004* | “Karuna faction” defected from LTTE, was initially defeated by LTTE, but then joined forces secretly with the SLA |

December 26, 2004* | Asian tsunami devastated the eastern and northern regions dominated by the LTTE, which resulted in a lull in hostilities. Death toll for Sri Lanka was set at 30,000. |

2005* | Tensions increased as the LTTE accused the government of refusing to distribute tsunami aid to Tamil areas in an attempt to force a settlement on the LTTE |

August 2005† | LTTE assassination of Foreign Minister Lakshman Kadirgamar |

2006* | The ceasefire eroded |

April 2006* | Peace talks were canceled as violence escalated in the east |

July 2006* | Eelam War IV began at the end of July |

2007* | Fighting continued, with government mounting offensives on all fronts |

January 2, 2008* | The government officially abrogated the ceasefire of 2002 followed by the SLMM departure on January 16. Government forces continued on the offensive against the LTTE, which fiercely resisted but was becoming increasingly isolated. |

January 2008† | LTTE assassination of member of Parliament from the United National Party, T. Maheswaran |

January 2008† | LTTE assassination of Nation-Building Minister D. M. Dassanayake |

February 2008† | Assassination of two members of the group Tamil Makkal Viduthalai Pulikal (TMVP) by the LTTE |

April 2008† | Assassination of Highway Minister Jeyaraj Fernandopulle |

January 9, 2009* | Government forces won the battle for Kilinochchi and retook the Elephant Pass |

2009* | Government offensives won victory after victory as it forced LTTE troops into a smaller and smaller territory |

May 18, 2009 | Government declared victory over the LTTE |

May 19, 2009 | Government announced that Prabhakaran’s body had been found |

April 2011‡ | UN declared that both the Sri Lankan government and the LTTE committed atrocities against civilians during the civil war and called for an international investigation |

March 2012‡ | UN Human Rights Council urged Sri Lanka to investigate war crimes. Sri Lanka argued this violates its sovereign rights. |

Sources: *Keesing’s World; †Bhattacharji (2009); ‡BBC News (2015a). | |

Sri Lanka gained its independence from the United Kingdom (UK) in 1948. Since that time it has been plagued with violent conflict. As mentioned previously, the violence has centered on the relations between Sri Lanka’s ethnic groups, the majority Sinhala (74 percent), who are largely Buddhist, and the minority Tamils (18 percent), who are predominantly Hindu. The country’s religious fragmentation also includes about 7.8 percent Muslims, a group that has been targeted with discrimination and violence recently. The Tamils are further divided by the distinction between the Ceylon Tamils and Indian Tamils. Ceylon Tamils have a long history on the island, and many seek to have their ancestral territories turned over to them to establish an ethnic homeland (EELAM). The Indian Tamils were brought over to work on tea plantations in the nineteenth century and settled in the center of the country. They have exhibited limited interest in establishment of a homeland for Tamils and have not been prone to rebellion, in spite of the Sri Lankan government’s refusal to grant them citizenship. Various factions of Sinhala and Tamils disagreed about strategies and the desirability of a mediated end to the fighting.

In elections, the Buddhist Sinhala identity was championed by political parties and student movements, culminating in the development of the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP) in the 1970s. The JVP’S tactics and importance varied over time. It attempted to overthrow the government in 1971 when it staged a major revolt. The participants in the movement were largely poor, rural Sinhalese who were frustrated with their lack of opportunity (Tambiah 1986). This action brought about a disproportionately brutal governmental repression resulting in an estimated twenty thousand deaths within a few weeks’ time (CQ Press 2007b; Tambiah 1986). The group returned to prominence in 1989–1990, which is discussed in greater detail below.

The most important, powerful, and persistent Tamil group in Sri Lanka was the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE or Tamil Tigers), which formed in 1978 as a student uprising. Over the course of the conflict, there were other groups that emerged to champion the cause of the Tamil people. Some sought a political solution (Tamil United Liberation Front, or TULF, for example), while others fought for independence (such as the LTTE). Even among the groups dedicated to the concept of Eelam, however, there was disagreement about the strategies and tactics that were acceptable and the extent to which the LTTE should end up ruling the new state once it was achieved. There were additional factions between the native Tamils and those that immigrated to Sri Lanka from Tamil Nadu to work on tea plantations during the British colonial period. In later stages of the conflict, there was also a major divide between the eastern and northern Tamil factions, with the east complaining that the north was ne glecting its interests. Singer argues that at the “height of Tamil militancy there were at least five major militant groups and at least 32 factions among them” (Singer 1992, 714). None of these challengers to the LTTE’S power lasted long against dedicated LTTE resistance. Throughout the conflicts with other groups the leader of the LTTE, Velupillai Prabhakaran, decried the disunity as undermining the Tamil cause and claimed to be in favor of the various groups uniting (Pratap 1984; Hindu 1986; annual Heroes Day speeches). However, his actions to eradicate competing groups are not indicative of such a desire. It is possible that the Tamils could have fared better against the Sri Lankan government if the various Tamil factions had been able to engage in collective action rather than fighting among themselves (Lilja 2010). However, the divide between the eastern and northern Tamils and the fear some had of Prabhakaran’s dominance kept such unity from ever developing.

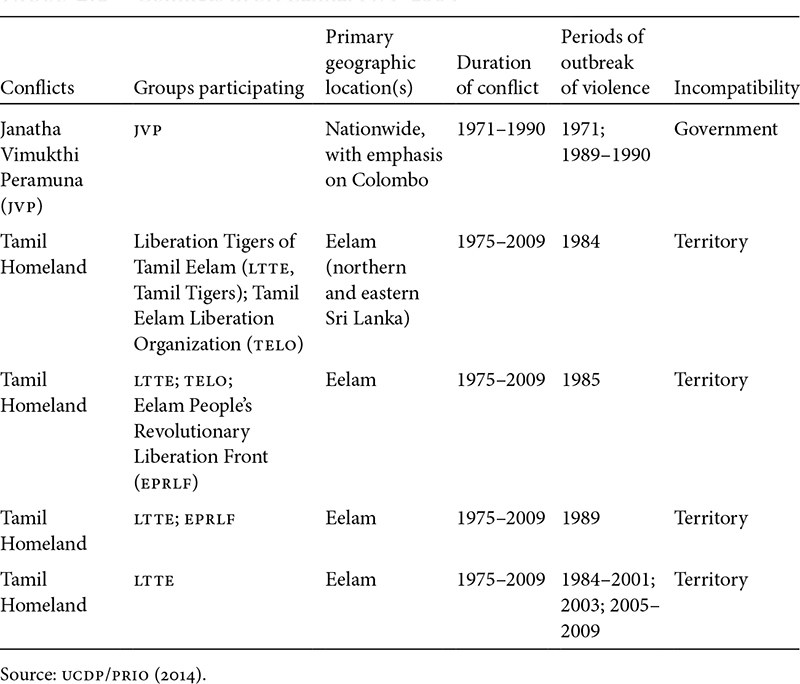

TABLE 4.2 Conflicts in Sri Lanka, 1971–2009

The conflict was characterized by continued strikes and retaliatory attacks. Both the government forces and the rebellious groups seemed unconcerned about civilian casualties. The LTTE was an innovative group that engaged in a wide variety of guerrilla and terrorist tactics in its attempts to address the power asymmetry it had with the government. It pioneered (invented, per the FBI [Bhattacharji 2009]) the use of suicide vests, engaged in suicide bombings as a strategic campaign, extensively involved women in the organization, had a small air force and navy, used chemical weapons at one point in an attempt to keep the government from increasing its capacity, deployed landmines in large numbers (estimated in 2002 to be over 1.5 million), and had an international system for fundraising and training. The group reportedly also trafficked in drugs to raise funds. The group was so sophisticated that in 2007 its air force carried out small-scale aerial bombing campaigns (Saddique 2007). All these actions were undertaken to increase group capacity relative to the government. The Sri Lankan armed forces engaged in numerous large-scale bombings and military campaigns geared toward isolating or eradicating the LTTE.

The LTTE attacked both Sri Lankan military and civilian targets. Within the civilian population it particularly targeted Sinhala and Muslim citizens. It has been argued that the LTTE occasionally did this in order to draw the government’s fire, which it could then depict as repression in order to stimulate support in Sri Lanka and abroad (UCDP). It was also not uncommon for violence to erupt after elections (for instance, in 1958 and 1977) if portions of the society were concerned that the outcome of the election would disadvantage their group (Little 1994). The LTTE would also target Tamil civilians who were seen to be complicit to the government’s cause or any Tamil group that attempted to become a peer competitor for Tamil allegiance. The LTTE has been accused of using children as soldiers, sometimes kidnapping them and compelling them to serve (U.S. Department of State 2009c).

Throughout the conflict, the government declared states of emergency on a fairly regular basis. During such times, rights of citizens were constrained significantly. In 1961, for instance, all citizens who lived in the Jaffna district, which was dominated by Tamils, were required to surrender all firearms to the government (New York Times 1961). Other common government tactics to control the violence included restricting the flow of information by rescinding freedom of the press, banning foreign media from the country, or engaging in extensive censorship in times of struggle (De Silva 1981). This complicates information gathering about the conflict and throws suspicion on casualty counts circulated by the government, as independent verification was not common. Disappearances, mass arrests, and the holding of prisoners incommunicado and without charges for lengthy periods of time were also common practices.

The Sri Lankan civil war began in 1983. Periods of attempted negotiated settlement of the conflict have included 1985, 1989–1990, 1994–1995, and 2001–2002 (Nadarajah and Sriskandarajah 2005). Throughout the conflict Prabhakaran would use talks to his advantage, using the time, and sometimes intentionally delaying the proceedings, to rearm and rebuild the strength of his forces (Ramesh 2007).

The number of people killed in the civil war is estimated at about seventy-five thousand (New York Times 2009). In 2009, government forces defeated the Tamil Tigers and then proceeded to punish Tamil citizens for the actions of the Tigers. Since that time the Tamil-related violence in the country has diminished considerably. However, it is impossible to determine whether the conflict is truly terminated or if it is merely in a lull, as so little time has passed between the defeat of the Tamil Tigers and the publication of this book, and the grievances of Sri Lanka’s Tamils have yet to be addressed. While military defeat tends to bring about longer-lasting conflict termination, resurgence of violence after such a defeat is not unprecedented.

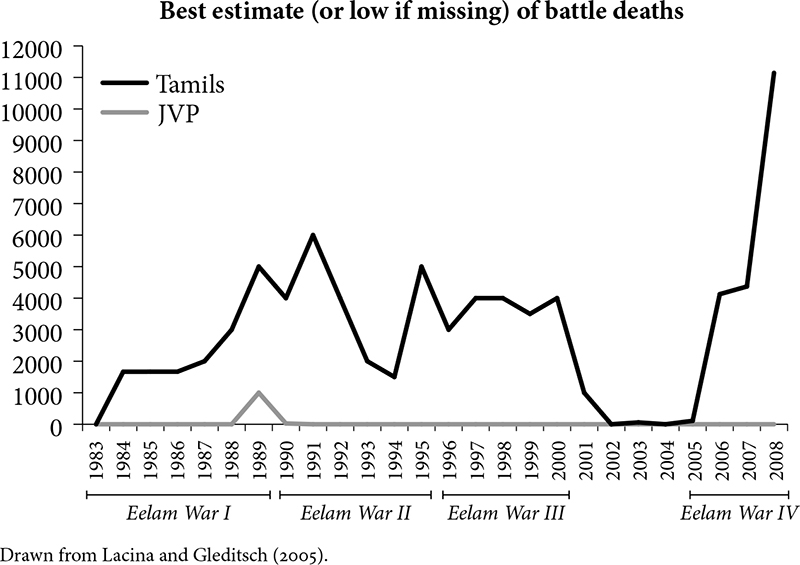

The Sri Lankan civil war has been divided into four distinct periods, which are referred to as Eelam Wars I–IV (UCDP). Each period begins with an increase in violence and ends with a subsequent decrease. The discussion of rivalry progression and conflict dynamics is divided into sections accordingly, as the Eelam Wars correspond with periods of escalation and de-escalation.

From the time of independence the Tamil population became increasingly dissatisfied with their situation and their ability to achieve any remedy for it through the policy process. In the early 1970s, student groups championing the rights of the Tamils flourished in the country. From this student movement, as many as thirty-six militant Tamil groups arose. A political party, the Tamil United Liberation Front (TULF), emerged. After political actions for change produced no progress, the TULF began organizing militant groups, one of which was the Tamil New Tigers (TNT, 1972–1976). This illustrates the shifting of the group’s goal from policy change and representation to the use of violence but was not yet a point where autonomy or independence was sought. Beginning in May 1976 the TNT was led by Velupillai Prabhakaran, who changed the group name to the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) and began the process of eliminating competitors inside and outside of his group (B. Hoffman 2009). Essentially, Prabhakaran assassinated anyone he deemed to be too moderate in pursuit of the Tamil cause.

The creation of the LTTE was followed by the government’s response in the form of the passage of the Prevention of Terrorism Act in 1979, which gave government forces the right to arrest, imprison, and hold incommunicado and without trial for up to eighteen months anyone accused of unlawful activity. Amazingly, the new law was applied retroactively, resulting in the abuse of many Tamils already in custody (DeVotta 2000). Beginning in the 1980s, numerous dissatisfied Tamil groups formed, with some supporting peaceful routes to change and others espousing the use of violence, but all had significant disagreements with the LTTE that were largely based on tactics and the perceived negative attitude about eastern Tamils held by those in the north. By the mid-1980s, there were almost forty identified groups devoted to the creation of a Tamil state (DeVotta 2009). At the same time as the LTTE was battling government forces, it was fighting against these groups to maintain its position as the sole voice of the Tamil cause. These conflicts were relatively short and limited in intensity. The LTTE’S superior training, funding, weapons, and discipline allowed it to defeat these competing groups (UCDP; DeVotta 2009).

FIGURE 4.2 Patterns of Violence in Sri Lanka, 1983–2009

Tensions between Sinhala and Tamil entities grew through the end of the 1970s and into the 1980s. Singer has argued that “there were ‘race riots’ in 1956, 1958, 1978, and finally the worst in July 1983 in which 1,000 innocent Tamils were killed and tens of thousands made homeless” (Singer 1992, 713). This 1983 riot was essential in mobilizing support behind the LTTE and other Tamil militant groups. In July 1983, an LTTE landmine killed thirteen Sinhala soldiers, resulting in enormous backlash against Tamils in the country. Sinhala citizens rioted; burned Tamil houses, businesses, and property; and killed and injured thousands of Tamils. According to Spencer, in some cases entire suburbs of the capital city of Colombo were “razed to the ground” (Spencer 1990, 616). Tambiah goes so far as to refer to the Sinhala rampage as an “orgy of killing of Tamils in Colombo” (Tambiah 1986, 15). Estimates of the number of Tamils killed in the fighting range from five hundred to two thousand (UCDP). Thousands more Tamils lost their property and became refugees. Enough of these refugees settled in Tamil Nadu in India to cause Indira Gandhi to become concerned, perhaps more about their potential to destabilize the region in India rather than about the Tamil plight, and to commit her government to training and financing Sri Lankan Tamil militants (Little 1994).

In the 1983 civil war the Sri Lankan government forces not only were slow to protect Tamil civilians (as they had been accused of previously), but openly assisted the Sinhala rioters or saw themselves as mere observers (DeVotta 2000). Regarding the violence, Human Rights Watch (1995b) observed that police and military personnel watched while Tamils were attacked, and in some cases they carried out violence against civilians themselves. Government officials were accused of stimulating and coordinating the anti-Tamil violence. Four days after the riots ended, President J. R. Jayawardene made a statement in which he decried the violence perpetrated by Tamil groups rather than condemning the pro-Sinhala attacks (Human Rights Watch 1995b, 88–89). One of the government’s responses to the beginning of the civil war was the passage of a controversial constitutional amendment in August 1983 that prohibited support or advocacy of independence that would threaten the country’s territorial integrity (Nadarajah and Sriskandarajah 2005).

The LTTE used these events to their benefit, emphasizing the violence and government’s disinterest in stopping it to recruit new members, raise funds domestically and with the Tamil diaspora abroad,1 and purchase weapons. These were clearly efforts to increase the group’s capacity. Throughout the conflict, the LTTE shifted funding and weapons sources as international actors altered in their backing of the group, which served to diminish the group’s capacity. Typically the support came from entities within states that had a significant Tamil diaspora presence. Obtaining resources became increasingly difficult as more and more states deemed the LTTE a terrorist organization and prohibited trade and financing arrangements with the group. By August 1984, the LTTE forces had swelled in numbers, were using more sophisticated weapons, and were shifting somewhat from guerrilla tactics to sustained attacks (Keesing’s World, September 1984, 33099). This fed an increase in the violence in the conflict as the LTTE’S increased capacity allowed it to combat government forces more effectively.

Once the war broke out in 1983, the Indian government began to train and equip the Tamils, who had close ties to the Indian state of Tamil Nadu. The LTTE drew on support from this area of India for much of its existence (maintaining and increasing its capacity), though the sponsorship of these activities shifted from official Indian government support to that of the citizens of Tamil Nadu when, in 1985, peace talks between Sri Lanka and the LTTE failed and India began to push for peace along a different path. Hassan argues that this was, at least in part, due to India’s desire to keep the Sri Lankan Tamil activities from stimulating dissent in Tamil Nadu (Hassan 2009, 7). The flight of thousands of Sri Lankan Tamils to Tamil Nadu to avoid the violence added to the Indian dilemma.

The 1985 peace talks were facilitated by Rajiv Gandhi but failed to make progress. Tamil political groups came together to form an umbrella organization to represent Tamils and agreed on demands that they should put before the government. These included recognition of Sri Lankan Tamils as a separate nationality, creation of a Tamil homeland by joining the northern and eastern sectors, and the right of all Tamils residing in the country to citizenship (which was denied to Indian Tamils at the time). The government refused to even consider these points as a start for negotiations. The Tamil United Liberation Front (TULF) then countered in December with an autonomy arrangement, which would have given the Tamils a high level of local autonomy, loosely based on the Indian model of federalism (Pfaffenberger 1987). While the government argued it could acquiesce to some of these demands, it refused to allow for the uniting of the northern and eastern regions or its designation as a homeland for the Tamil population. This undermined the negotiation process. While the moderate TULF found the government’s position “reasonable” (Pfaffenberger 1987, 158), the more militant factions rejected it. Prabhakaran complained that the TULF was “retarding the liberation struggle,” that it failed to take concrete steps, and that it was attempting to stifle the revolution (Pratap 1984, 2).

In 1985 and then again in October and November 1986, the government increased its arms acquisitions (Sislin and Pearson 2006). These purchases, which represent clear attempts by the government to increase its capacity, preceded the initiation of major government offensives against Tamil-held areas (Sislin and Pearson 2006). These included cutting the LTTE’S supply lines (Hindu 1986).

Subsequent negotiations between the Sri Lankan and Indian governments led to the signing of the Indo–Sri Lankan Agreement on July 29, 1987. Shortly after the agreement was signed, thousands of Indian troops were engaged in Sri Lanka under the auspices of the Indian Peacekeeping Force (IPKF, numbering around eighty thousand troops). It is perhaps telling that the agreement involved the governments of the two countries, but not any of the rebel organizations. From the Tamil perspective, the most significant provision of the agreement was that it allowed for the northern and eastern provinces to be merged into a single administrative district and recognized those areas as the traditional Tamil homeland. In addition, the agreement provided for amnesty for political prisoners (Rupesinghe 1988). Prabhakaran reluctantly agreed to a ceasefire for a short time when it became clear the agreement was going to go ahead over his objections (Ghosh 1999). However, the Tamils soon took up arms to continue the fight for a Tamil homeland against the government, IPKF, and Tamils they identified as being complicit with the agreement.

India’s involvement in both peacekeeping and conflict is explained by Carment and James (1996) as stemming from three main factors. First was the Sri Lankan refusal to offer permanent citizenship to the Indian Tamils who had lived in the country for generations, resulting in the more than 975,000 Indian Tamils being stateless people. Second was the Congress Party’s need to maintain the support of two major Tamil Nadu parties in order to win the state. Third was the existing strong ties between the Sri Lankan Tamils and the citizens of Tamil Nadu, including military training camps (Carment and James 1996, 543–544). A fourth possible explanation is provided by DeVotta (2009), who argues that the Indian government was displeased by the Western-leaning tendencies of the Sri Lankan government and was seeking to undermine it (1029). From an outsider’s perspective, the perplexing thing about this accord is that it was intended to restore peace to Sri Lanka but included no LTTE representation in its negotiations or implementation. The announcement of the agreement surprised many and, perhaps as a result, was met with mixed reactions (Rupesinghe 1988).

While the Indian troops were sent to Sri Lanka as a peacekeeping force, the situation devolved into an armed struggle, effectively intensifying the violence that was already occurring in the country. By October the LTTE was fully engaged against the IPKF. The Sinhala rejected the presence of the IPKF almost as intensely as the LTTE did. This resulted in the eventual collaboration between the Sri Lankan government, led at this point by President Ranasinghe Premadasa, and the LTTE to drive the Indian forces out of the country (Hopgood 2005, 49). This included talks with the LTTE, which had been weakened by its struggle against the IPKF (Little 1994). The situation strained relations between Sri Lanka and India, as a timetable for the removal of the Indian troops was difficult to agree upon and implement. Fighting throughout the time that the Indian troops were in Sri Lanka was fierce. According to Little (1994), the conflict with the IPKF had the unintentional consequence of strengthening the LTTE and extending the conflict.

The Indo–Sri Lankan Agreement, in particular its offer of amnesty to Tamil militants who denounced violence and engaged politically, also had the effect of turning some Sinhalese forces and left-wing actors against the Indian troops and Sri Lankan government (CQ Press 2007b). This brought about episodic violence as the JVP returned to prominence and gained strength in the aftermath of the signing of the agreement. The JVP “launched a death squad campaign in which backers of moderation among both communities [Sinhala and Tamil] were systematically targeted” (Sisk 2009, 154). Such violence from a group devoted to Buddhism seems out of character. However, the actions were undertaken as an obligation in defense of the faith. The violence has also been attributed to young, impoverished, extremist Buddhist monks who felt deprived within the Sri Lankan political system (Little 1994). By the end of the year, the group had significantly increased its capacity by amassing weaponry and was engaged in assassination of its competitors. This included the targeting of the families of prominent members of the Sri Lankan military. The government’s response was repressive, with the ensuing conflict causing over a thousand fatalities before the end of 1989. The violence continued, though at a lower level (sixty-one fatalities), into 1990 (UCDP). Through the remainder of the conflict, the JVP stood in opposition to any peace settlement that devolved power or gave autonomy to Tamil regions. However, the group did so through its role as a political party rather than through violence.

The constant fighting and conflict with the Indian military as well as that of Sri Lanka had significantly diminished the capacity of the LTTE. This resulted in its willingness to seek accommodation and the signing of a ceasefire agreement in 1987 (UCDP). Another factor that contributed to the group’s fatigue was the fact that during 1987 it was also engaged in armed conflict with the Tamil Eelam Liberation Organization (TELO). This was related to the north/east divide among Sri Lankan Tamils, the fact that Prabharakan wanted the LTTE to be the sole voice for Tamils, and his belief that other Tamil organizations were too moderate. TELO was the second most powerful Tamil group at the time but had poor discipline and leadership, leading to its defeat by the LTTE (J. Richards 2014). Though the LTTE emerged victorious, this additional fight divided its capacity between the conflicts with TELO and government forces, further diminishing its capacity.

Indian troops were finally withdrawn in March 1990. By that time, the combined fatality rate was over twelve thousand, with another five thousand wounded (Hassan 2009).

In spite of the ceasefire to which Premadasa had reluctantly agreed, once the Indian forces withdrew from the country the LTTE reengaged in the fight with the Sri Lankan government. In general, the 1990s saw a shift in the nature of warfare in Sri Lanka from guerilla attacks on government forces to more traditional military offensives between territories controlled by either side (Nadarajah and Sriskandarajah 2005). In spite of the fact that the group had been weakened, it retained sufficient capacity to engage the government.

While the Sri Lankan Armed Forces enjoyed significant numerical superiority over the LTTE rebels in the 1990s (240,000 Sri Lankan Armed Forces versus about 10,000 rebels), the government attempted to further increase its capacity by promoting anti-LTTE paramilitary forces (Nieto 2008, 578). This may have been due to the poor preparation of the Sri Lankan Armed Forces. Several sources point to the limited training and equipment in the Sri Lankan Army as a contributing factor in government’s inability to defeat the LTTE (Nieto 2008; Hopgood 2005).

In early 1990, the LTTE stepped up its attacks against Sri Lankan military bases and managed to seize control of the Jaffna peninsula in the north, which became the seat of power for the LTTE until 1995 (UCDP). In early June the LTTE launched a series of attacks on police stations. The government responded with massive bombing campaigns, which included the use of napalm. On July 22, a mass grave was uncovered by government forces. In it were as many as two hundred dead policemen who had been blindfolded and shot in the back of the head. They were believed to be from the more than six hundred who were captured during the LTTE police station raids. From June 11 to August 17, 1990, as many as 3,350 deaths were recorded as resulting from the conflict (Bandarage 2009).

Another important LTTE event in 1990 occurred when it surrounded a military encampment in East Kiran, a peninsula in the Batticaola district, on June 11. The LTTE continued to hold the camp under siege until June 21. The government succeeded in breaking the siege by successfully bringing in a column of troops by sea. The importance of the incident was the reaction of the LTTE to the impending arrival of the relief troops. According to Bruce Hoffman (2009), when the LTTE sensed that the advantage in capacity would shift to the government with the arrival of reinforcements, it deployed barrels of chlorine gas upwind of the besieged camp (469–470). Hoffman attributes the use of chemical weapons, at least in part, to the LTTE’S diminished ability to acquire and import quality weapons at this time. This is a clear example of a group’s shift in tactics based on a perceived impending shift in the relative capacity between itself and the government.

Violence during Eelam War II peaked with an estimated 6,400 fatalities in 1991 (UCDP). In the late 1980s, the Jayawardene government signed a proclamation that merged the northern and eastern provinces for administrative purposes, which was a stated goal of the Tamils. This created the North-East Provincial Council. In 1990, before the complete withdrawal of Indian troops, the North-East Provincial Council approved a resolution declaring independence for the region. In June 1990, Premadasa dissolved the council and called for new elections. In response, the LTTE engaged in a new wave of violence against both government and competitive Tamil entities (CQ Press 2007b).

In November 1993 the government suffered its worst losses to date when a single LTTE attack killed more than 500 soldiers and forced another 1,500 to withdraw from a base in Jaffna. This defeat, scandals that had weakened Premadasa, and his subsequent assassination in 1993 may have contributed to the government’s willingness to enter into negotiations in 1994 and contributed to the lull in the conflict (Little 1994; Gargan 1993). Prabhakaran indicated that he hoped the new government would be amenable to talks but emphasized that the provision of autonomy was an important factor in whether he would find peace proposals acceptable (Prabhakaran 1994). This marked the end of Eelam War II.

Chandrika Kumaratunga became president of the country in 1993. Her father had been the prime minister of Sri Lanka until 1959, when a Buddhist monk assassinated him. Her husband was assassinated in 1988, just as his political career had started to progress (Dugger 2000). She took office in an environment of national dissatisfaction with the costs of the continued conflict and a belief that military victory could not be achieved. She “came to power with a mass sentiment that through negotiation she would pursue an end to the war” (Sisk 2009, 154). Negotiations began again in 1994, resulting in a ceasefire on January 8, 1995. There was agreement that power would be devolved to the Tamil areas. However, the LTTE exited the talks in 1995, after which the government continued to negotiate with moderate Tamil groups in an attempt to marginalize the LTTE (Sisk 2009; Prabhakaran 1995). The peace process was, of course, opposed by Sinhala and Tamil extremists.

When the LTTE intensified its violence in response to the failure of the talks, the government shifted its policy for dealing with the group. It had been willing to negotiate a settlement of the conflict. Significant damages imposed on the government by the LTTE in April 1995 shocked it into action, and its goal shifted toward one of complete military victory (UCDP). The government felt the urgent need to increase its capacity versus the rebels (Saravanamuttu 2000, 156).

July 1995 marked the beginning of another massive offensive (Leap Forward) by the Sri Lankan government. The aim of the action was to weaken the LTTE in its stronghold of Jaffna and reinitiate peace talks with the group. The government mobilized over ten thousand troops along with air and sea missions in the Jaffna peninsula. The LTTE initially offered little resistance, but after five days it mounted a serious counteroffensive that included surface-to-air missiles and a large number of suicide missions (Bullion 1995). This was followed later in 1995 by the Riviresa offensive, which mobilized twenty-one thousand soldiers and heavy artillery in Jaffna. This effort caused over five hundred thousand refugees to flee the region and eventually trapped two thousand LTTE rebels in a single town. In November the government declared that military spending had increased by 33 percent to support its attempts to intensify military operations (Subramanian 1995). The Sri Lankan government was clearly emphasizing increasing its capacity by concentrating forces in problem areas and by prioritizing military spending.

A new agreement was released in August 1995. It gave significant autonomy to Tamil areas. The agreement failed to have impact, however, as some Sinhala felt it gave too much to the Tamils while extremist Tamil populations felt it gave too little. The LTTE responded with a major attack in Colombo, marking the resumption of hostilities.

In 1995 the Sri Lankan government achieved a major victory as it drove the LTTE from its long-term stronghold in Jaffna. By 1996 the government had achieved additional military victories, effectively driving the LTTE into the jungles and putting them on the defensive from 1996 to 1998. This defensive period coincided with the October 1997 U.S. Department of State designation of the LTTE as a foreign terrorist organization (FTO; U.S. Department of State 2009c). This U.S. action impacted the LTTE’S ability to raise funds, acquire weapons, and gain concessions from the international system. During this time, the LTTE strategy in the north was primarily a conventional war against the Sri Lankan military. In the east the strategy was more focused on guerilla tactics, while in the south the group engaged in a bombing campaign (UCDP). This can be attributed to the fact that the Tamils in the north had a stronger capacity versus that of the government than those to the east.

In July 1996, the LTTE overran a government base at Mullaittivu in the northeast of the island, inflicting heavy losses on government forces. The government responded with a massive offensive against Kilinochichi, where the LTTE had relocated its headquarters after being driven out of Jaffna. It seems there were fewer than five hundred combined government and LTTE fatalities, but hundreds of thousands of civilians were displaced (Human Rights Watch 1997).

Two major attacks by the LTTE took place in the late 1990s. The first occurred when a four-hundred-kilogram bomb was detonated in the business district of Colombo on October 15, 1997, killing eighteen and injuring more than one hundred. Two possible motives have been given for the attack: that the group was attempting to raise morale after suffering losses in Jaffna or that the attack was a response to the U.S. State Department’s designation of the LTTE as a foreign terrorist organization (De Rosayro 1997).

The second major attack was on January 25, 1998, when the LTTE used an explosives-filled truck to attack one of the holiest Buddhist temples in Sri Lanka, the Temple of the Tooth. The temple housed a tooth that is believed to be one of Lord Buddha’s and was revered as the holiest Buddhist site on the island (DeVotta 2000, 55). It had, however, become closely associated with Sinhala chauvinism, as successive prime ministers gave speeches from the temple in which they emphasized the importance and dominance of Buddhism in the country (Little 1994). The Sinhala Buddhists believe that Sri Lanka is intended to be a country dedicated to the preservation of Buddhism (Pfaffenberger 1987, 157), making this a particularly despicable attack in their eyes. This sparked a major round of ethnic rioting as Sinhala and Tamil nationalists clashed, pushing fatality rates up to over 3,500 in 1998 as compared to the previous two years, when there were fewer than 3,000 battle deaths (UCDP). In response to the LTTE’S attack on the Temple of the Tooth, the government outlawed the group. The government had previously avoided banning the organization, as that would complicate peace negotiations and any attempt to grant the Tamils autonomy (Human Rights Watch 1999b; Economist 1998). An outlawed organization would lack standing in such legal venues. These two attacks on civilian targets were likely the result of the LTTE’S recent losses and associated reduction in capacity.

By June 1998, the government had banned all news coverage of the civil war by either local or foreign media (Human Rights Watch 1999b). The government claimed to have gained control of a number of key sites in September 1998, including the highway that serves as a lifeline for Jaffna. Over a thousand died in the fighting. On September 6, Prabhakaran called for talks with the government (Rotberg 1999).

The LTTE had halted the Sri Lankan Army’s offensive and wiped out the gains they had achieved through their stepped-up operations by November 1999. The LTTE recaptured several military bases and the supply road to the Jaffna peninsula. On November 27, Prabhakaran called for the government to remove its forces from Tamil lands and enter into peace talks (Prabhakaran 1999). This was typical of Prabhakaran’s tendency to attempt to negotiate from a position of power. While the government was engaged in track two diplomacy consistently, a formal round of talks did not emerge from Prabhakaran’s call.

The late 1990s were a period of rearmament for the government (UCDP). It continued to seek weapons and counterterrorism training internationally throughout the early 2000s, with those activities becoming increasingly effective after the 9/11 attacks and the global antiterrorism actions that followed. The Sri Lankan government seemed at this time to be focusing on increasing its capacity.

Track two negotiations (e.g., typically behind-the-scenes discussions) had taken place in the 1990s and carried over into the early twenty-first century. These laid the groundwork for resumption of talks in 2000, with Norway agreeing to serve as mediator.

Fighting raged throughout 2000. By the end of the year, in spite of some significant military accomplishments, the LTTE was exhausted, sought negotiations, and declared a unilateral ceasefire (UCDP; Sisk 2009). This resulted in a de-escalation of the conflict and the eventual end of Eelam War III. The government maintained its insistence that the group agree to negotiate unconditionally, which hindered talks until 2001. Those talks, the subsequent ceasefire agreement, and the additional talks that followed are discussed further in the section on negotiations. Importantly, however, throughout the negotiations period the LTTE exhibited a willingness to accept an autonomy agreement rather than independence (UCDP), marking a significant shift in the group goal. Pressure was put on the LTTE by the 9/11 attacks, which caused the UK and other world powers to join the United States in designating the group a terrorist organization (Sisk 2009). The increased international activities to interdict the flow of weapons to terrorist organizations and block fundraising and the movement of money internationally significantly impacted the LTTE’S ability to maintain its capacity level (Sisk 2009; Ganguly 2004). In addition to the troubles the LTTE was experiencing, “clearly one major incentive for both sides was that the war had reached the point of stalemate” (CQ Press 2003).

While there was a lull in the fighting from 2001 to the resumption of violence in 2005, there was a great deal of ongoing activity between the government and LTTE. A memorandum of Cessation of Hostilities was signed on February 22, 2002. The agreement, which was never very effective, included provisions for decommissioning weapons, opening the Elephant Pass road, and permitting civilian air traffic into Jaffna (Sisk 2009). One of its primary functions was to facilitate six rounds of talks from September 2002 to 2003. The focus of those talks was on humanitarian issues, reconstruction, normalization of relations, and, at least at one point in November and December 2002, a political solution to the underlying dispute (UCDP). Mayilvaganan (2009) has argued that these negotiations never bore much fruit due to the lack of sincerity on both sides (25). This negotiation process differed from others in that a peacekeeping mission was established to monitor the ceasefire. It was called the Sri Lanka Monitoring Mission (SLMM) and consisted of members from Norway, Sweden, Finland, Denmark, and Iceland (Hassan 2009). In spite of the ceasefire and the SLMM, neither side was willing to discuss or come to an agreement on the core issues of the conflict. The ceasefire was violated frequently, and the situation gradually returned to one of insecurity and violence. The SLMM withdrew in 2008, and the government launched renewed offensives against the LTTE. Funding to the military was increased, which allowed for a 40 percent increase in the size of the Sri Lankan Armed Forces (Hassan 2009).

By April 2003, however, the LTTE accused government negotiators of slow implementation of the agreed-upon reconstruction activities and “attempting to marginalize the organization” (UCDP). This resulted in a deadlock in negotiations and the eventual LTTE withdrawal, which marked an endpoint of effective negotiations in the country. While other attempts were made, they had little to no impact on either side’s conduct, regardless of their content or intensity.

The situation was exacerbated by an important splintering event in LTTE history in March 2004. LTTE Colonel V. Muralitharan (known as Karuna) wrote to Prabhakaran to express his dismay at what he felt was the mistreatment of the eastern Tamils by the LTTE and requested that the eastern wing be permitted to function separately (Ratnayake 2004). He argued that the northern leaders of the movement treated the eastern members as second class and that eastern leaders were denied adequate representation in leadership positions (Sri Lanka Project 2004). Karuna also complained separately about eastern troops being deployed to northern battle areas, leaving their home territories unprotected (Ratnayake 2004). In a second letter, Karuna wrote to the SLMM and asked if he could arrange a separate truce for his troops. Karuna was subsequently expelled from the LTTE on March 6. He took with him five to six thousand fighters, or about a third of the LTTE’S military forces (Ratnayake 2004). This move clearly diminished the LTTE’S capacity, especially in the north of the country, from which Karuna’s forces would have been drawn. Ratnayake (2004) argues that this rift was actually the manifestation of wealthy Tamil interests in the north and east attempting to negotiate the best possible peace for their region, at the potential expense of Tamils elsewhere. This may indicate that Karuna had doubts that the LTTE had the capacity to defeat the government. Lilja (2010) argues that while the LTTE had the leadership and capacity to mobilize its members for war, it lacked comparable skill to lead them toward peace.

Karuna’s military battled Prabhakaran’s LTTE for control of eastern territories and was largely defeated (CQ Press 2007b). He then shifted strategies toward one of seeking political accommodation for the eastern Tamils from the government. Karuna eventually started a political party and served in the Sri Lankan government. For the negotiations process, the Karuna split was important in that it exacerbated tensions between the LTTE and the government and seriously weakened the LTTE. The LTTE declared that the government was supporting Karuna’s faction in an attempt to diminish the LTTE’S power (Wax 2009). While this may not have been the government’s intent, it certainly was one of the outcomes.

The ceasefire of 2002 was frequently violated by both sides. While there had been hope that the 2004 Asian tsunami would create a more peaceful environment, this was not to be. In the immediate aftermath of the disaster, all sides seemed willing to put aside their grievances to respond to a true national tragedy. An estimated thirty thousand Sri Lankans were killed in the tsunami, with many of them in the contested eastern region. However, after this initial rapprochement, the tragedy became an additional bone of contention, as decisions about how to distribute international aid increased tensions and violence (CQ Press 2007a). It was June 2005 before a controversial deal could be struck that would allow the LTTE to have any share in the international funds pledged for tsunami relief efforts (Human Rights Watch 2006). Violence built significantly through 2005, and the ceasefire had collapsed completely by 2006. In particular, in April 2006 there was an LTTE campaign of suicide bombings against the military in Colombo,2 attacks against naval installations, and in May an attack on a naval convoy. By June the LTTE and the Sri Lankan government were fully engaged militarily (Sisk 2009, 160).

In 2006, Sri Lankan president Mahinda Rajapaksa maintained a two-pronged policy toward the LTTE, seeking negotiations at the same time as retaliating for any damages inflicted by the group. However, as the year progressed, the government withdrew officially from the 2002 ceasefire, negotiations were abandoned, and fighting intensified. August 2006 saw an increase in the intensity of the violence as the LTTE undertook a large number of attacks. In October 2006, the LTTE sent peace monitors with the SLMM home to their respective EU countries. It has been argued that the LTTE’S actions in the latter half of 2006 were designed to sidetrack talks that were to take place in late October in Geneva (CQ Press 2007a). In the aftermath of those talks, it seemed neither side was sincere in its desire to participate. Rather, international aid donors had pressured both into attending (Chopra 2006).

On June 19, 2007, President Mahinda Rajapaksa sought to increase government capacity through the expedited recruitment of fifty thousand additional troops in order to “maintain the momentum of military successes in the east” (Lanka Newspapers 2007). The expansion was to be funded through cutbacks in other government spending.

Sri Lankan government forces undertook major ground offensives against the LTTE in 2007, particularly in the east of the country, bringing “the eastern part of the country back under government control for the first time since 1994” (UCDP). Governmental offensives in 2007 significantly weakened the LTTE (UCDP), which certainly contributed to its tactical decision making as the war came to its conclusion. The LTTE’S actions in the last phases of the conflict have been condemned (as have the government’s, which are discussed below) by the United Nations and various humanitarian organizations. After the government created safe zones into which civilians could flee the fighting, LTTE actions denied civilians access to these secured areas. During this period, the LTTE has been accused of shooting civilians who were trying to leave conflict areas, firing artillery near known camps for internally displaced persons (IDP), using IDP and hospitals as shields for their camps and equipment, and continuing to carry out suicide attacks against civilians who were not in areas of active conflict (Report of the Secretary-General’s Panel 2011).

On January 2, 2008, the government officially declared its abrogation of the 2002 ceasefire agreement. The agreement had been ineffective for a while, but neither side wanted to be seen as the one that had ended it, so it remained in place (UCDP). The conflict escalated significantly after the announcement. In September 2008, the Sri Lankan Army started a major offensive to capture remaining rebel territories in the north (UCDP).

In February 2009, the LTTE issued a call for a ceasefire. The government, which had by this time managed to overtake all of the group’s strongholds and was close to a military victory, ridiculed and dismissed the ceasefire request (Fuller 2009). Fighting leading up to the government’s victory in May 2009 was intense and claimed thousands of lives (UCDP). The government captured the town of Kilinochichi, retook the Elephant Pass so it could supply Jaffna, captured numerous LTTE camps, and drove the group into an increasingly smaller area to the east. According to the International Crisis Group, almost all of the LTTE’S political and military leadership was killed in the fighting (UCDP).

As mentioned previously, the government’s ruthless execution of the last phases of the war has been decried by the United Nations and many international human rights organizations. In response to the international community’s concerns over the plight of civilians in conflict areas, the government set up safety zones to which they could flee. The Sri Lankan government is accused of using large-scale shelling against various areas during the last phases of the conflict, including the safety zones. Like the LTTE, the Sri Lankan government has been accused of significant human rights violations in the conduct of the conflict, especially at these late stages. It fired into the safe zones established to protect civilians and shelled humanitarian relief areas including a UN hub and International Committee of the Red Cross and Red Crescent ships. The government stands accused, in fact, of causing the majority of civilian casualties toward the end of the conflict through its indiscriminant shelling campaigns (Report of the Secretary-General’s Panel 2011).

The capacity of the LTTE organization plummeted with the death of Prabhakaran in May 2009. Not only had the organization’s numbers been decimated by the government’s onslaught, but it also lost the central figure of the group’s capacity to mobilize support at home and abroad. His leadership style was totalitarian and consistent with Weber’s definition of charismatic leadership, which emphasized that the leader’s personality is fundamental to the group’s existence (Jordan 2009, 726; Weber 1964, 358). Leadership of the LTTE was so closely tied to Prabhakaran that, according to Hoffman, members pledged their allegiance to him each day rather than to the country or the cause (Hoffman 2009, 466). Both Nieto (2008, 583) and Sisk (2009, 160) predicted that peace would not be possible until Prabhakaran either died or stepped down from power.

After the cessation of hostilities, in 2010, the European Union ended Sri Lanka’s preferential trade relationship with it based on the human rights abuses committed by the government during the war. In April 2011, the UN argued that both sides had committed atrocities against civilians and recommended an investigation into war crimes. This was followed in 2012 by a resolution of the UN Human Rights Council, which called for the Sri Lankan government to investigate its abuses, which was met with resistance from the Sri Lankan government, which argued that the demand violated its sovereignty. The UN’S calls were essentially rejected by the government, which said in August 2014 that a UN delegation sent to the country to conduct an independent investigation would not be allowed to enter the country (BBC News 2015a). In February 2015, the United Nations agreed to defer release of its report on potential war crimes after the Sri Lankan government argued that the country was experiencing a new era of cooperation. The United Nations agreed to delay the release of the report based on the government’s assurance that it would cooperate with the continued investigation and conduct a credible domestic investigation as well (Sengupta 2015).

Meanwhile, in the north and east of the country the Tamil National Alliance, an ethnic Tamil party, was consolidating political power. In 2011 elections, the group won two-thirds of the seats in local councils in the former war zone. In September 2013 elections, the Tamil National Alliance won seats in a semi-autonomous northern provincial council, with 78 percent of the vote (BBC News 2015a).

Relative capacity was clearly an important element in the continuing rivalry between the government of Sri Lanka and the LTTE. Both sides actively courted external support for funding, training, and weaponry. The tactics employed by the LTTE were impacted by its perception of its capacity, with more terrorism and guerrilla tactics being employed when it was at a disadvantage and more traditional tactics of warfare being used when it felt superior. In one remarkable instance, it even attempted to use chemical warfare to keep the government from expanding its capacity in a specific geographic location.

Intervention also impacted the patterns of violence. Indian intervention mobilized both the JVP and the LTTE into higher levels of violence as both sides objected to the presence of Indian forces on the island. Foreign diplomacy also was an intervening factor. The U.S. inclusion of the LTTE on its list of foreign terrorist organizations may have triggered an escalation of LTTE violence. It certainly constrained the group’s fundraising and weapons acquisition activities. The events of 9/11 further hindered the group’s ability to increase its capacity. In the aftermath of that terrible incident of terrorism, countries around the world increased their restrictions on dealings of all types with designated terrorist organizations.

One of the relatively distinctive aspects of this case as compared to others in the book is the incredible importance of charismatic leadership on the rivalry. Quality of leadership is a factor in capacity. Prabhakaran’s personal power and charisma emboldened and strengthened the LTTE. Group members reportedly felt aligned with him against the government, rather than feeling allegiance to a cause or the country. This benefited the group so long as he lived, but it became a serious weakness upon his demise. No reports were found that indicated he was grooming a successor. If he were, it likely would have been among his top generals, however, and many of those were killed or captured along with him in 2009. The group’s capacity was so tied to the personal power of Prabhakaran that it is unclear if the group could have continued under different leadership.

In the Sri Lankan case we see both sides seeking to negotiate when they have the advantage as well as when they are at a disadvantage to their competitor. Prabhakaran preferred to negotiate from a position of power, but when his group faced truly dire circumstances, he might also request talks.

This case also illustrates a progression in group goal. Initially, when there were student riots, the goal was to gain awareness for the unfair treatment of the Tamils and to gain policy change to help alleviate their plight. When such policies were not forthcoming, the TULF and subsequently LTTE sought various autonomy arrangements with the government. The JVP’S vigorous objection to any arrangement that might have benefited the Tamils kept autonomy agreements from coming to fruition.

As mentioned previously, at the time of publication of this book it is still too early to determine if the rivalry has indeed terminated. Government forces managed to damage the LTTE organization profoundly with the killing of Prabhakaran and most of the other group leaders in 2009. However, as Hassan (2009) argues regarding Sri Lanka and others have argued more generally, military victory did nothing to address the underlying grievances that drove the Tamils to violence in the first place. In contrast, others argue that military victories, though violent, lead to longer-lasting peace than negotiated settlements. The fact that Karuna and representatives of more moderate Tamil groups have received seats in government may help to satisfy some Tamils that their voices are being heard. It may also be that the group capacity of the LTTE was so devastated by the government that it cannot resurge in the future. It is simply too early to tell if the rivalry is truly over. However, there were no reports of Tamil violence found for 2015, which could indicate that Tamils are currently satisfied with trying to have their grievances redressed through representation and policy change rather than through the use of violence.