Myanmar has experienced eight different intrastate conflicts (Gleditsch et al. 2002) and over thirty armed factions or rivals (Ballentine and Nitzschke 2003) in its short history, making it a country with a very complicated conflict history.1 It involves both ideological and identity-based rivalries. Despite the repressive nature of the ruling military junta (which has changed over the country’s history), the central government has never actually achieved control over its entire polity at any point, although it has certainly done better in this regard lately. The trajectories of the conflicts involved have been significantly impacted by the role of external actors, as well as intergroup collaborations. As a result, it is an ideal candidate to examine conflict dynamics when the state is faced with violence from multiple potential foes.

Myanmar stands out among the cases examined elsewhere in this book. Not only has conflict been lengthy and enduring in Myanmar, but the relationships that exist among the many conflict actors intertwine as interconflict collaboration unfolds or collapses. The country of Myanmar is situated in Southeast Asia bordering Thailand, Laos, China, India, and Bangladesh, which made cross-border activity with neighboring countries and rebels a major challenge. This access had a significant influence on the capacity of many nonstate actors and the choice of tactic employed by the groups involved. Grundy-Warr (1993) has suggested that political and military conflicts in Myanmar are best explained in light of the country’s cross-border space. First and foremost, the ability for rebels to find sanctuary from army pursuit allowed for some groups to employ hit-and-run tactics for long periods of time successfully. Thailand, in particular, provided consent for some of Myanmar’s rebel factions to establish bases on its soil beginning in 1954. This permission was revoked in 1988 when Thailand negotiated logging rights with the Rangoon government (Human Rights Watch 1998). Both decisions changed the capacity of rebels to wage their war against the government. Similarly, Bangladesh served as a sanctuary for others fleeing from governmental offensives several times over the country’s history. More recent decisions to close that border to refugees have led to a humanitarian disaster. In the north, the border with China benefited several Myanmar rivals through assistance and safe havens as well. In light of the country’s location relative to its neighbors, it is not surprising that this case involves more conflicts of the enduring nature than others examined in this book.

In addition, Myanmar’s terrain is ideal for groups engaged in guerrilla warfare. In particular, the central Irrawaddy delta, which is sandwiched between steep, rugged mountainous regions and jungle terrain, is well suited to such tactics. Guerrilla warfare is indeed the most prevalent form of violence employed by all rebel factions in the country. This terrain has allowed rivals to take and hold territory, effectively creating rebel group strongholds. The territory in the northeastern portion of the country bordering Laos is also ideal for growing poppies. Rebels have been able to capture this resource, increasing their capacity in the process. The money generated from the drug trade has also changed the nature of some groups from those engaged in identity-based secessionist movements to profit-driven splinter groups that have subsequently shifted their tactical choices.

The historical and cultural experience of Myanmar has also played into the trajectory of conflict within its borders. The terrain discussion is relevant to this experience. The lowlands and highlands of Myanmar are not only conducive to rebellion, but they also involve spatial dichotomies (Grundy-Warr 1993). The ethnic majorities that live in the highlands are distinct from the national majority Burman in the lowlands. These differences were exacerbated during colonialism, when the British decided to administer the Shan States and northern Burma, ethnically different areas from Burma proper, as separate, distinct entities (Taylor 2008; Holliday 2008). Divide-and-conquer techniques were employed in Arakan, with Rohingya Muslims receiving preferential treatment over Buddhist Rakhines. As independence approached, the leaders of the Shan States, including the Shan, Da-nu, Pa-O, and Wa, along with representatives from the Chin, Kachin, and Karen, met and formed the Supreme Council of the United Hill Peoples (SCOUHP). When they met again in February 1947 they did so with revolutionary leader Aung San, who agreed to full autonomy for the frontier areas and equality for all races, resulting in the Panglong Agreement (Ethnic Nationalities Council 2007; Silverstein 1997). Aung San was a leader whom other minorities could trust to fulfill this promise. However, he was assassinated in July of the same year. Given the historical animosities and cultural differences that were exacerbated during colonial times, the new Burman leaders that emerged were unable to establish that same relationship, nor did they fulfill the promise of the Panglong Agreement. The fact that it existed became a focal point for minorities living in the frontier areas whenever negotiations were introduced. In fact, the Ethnic Nationalities Council, located in Chaing Mai, Thailand, and representing the Arakan, Chin, Kachin, Karen, Karenni, Mon, and Shan States, still proclaimed “Long Live the Spirit of Panglong!” on its website commemorating the sixtieth anniversary of the agreement.

TABLE 5.1 Timeline of Key Events in Myanmar’s Conflicts, 1946–2003

Date | Event |

February 5, 1946 | Karen National Union established |

February 22, 1946 | Red Flag splintered from the Communist Party of Burma (CPB) |

March 1946 | Burmese Army began first counterinsurgency operations |

January 4, 1947 | Burma became independent |

March 1947 | Mon National Defense Organization established |

April 4, 1947 | CPB and Rangoon government experienced first bout of violence |

August 9, 1948 | Rebellion in Karenni states |

December 1948 | U Nu invited CPB leaders to peace talks, which were rejected |

April 6–8, 1948 | Inconclusive peace talks with Karen National Union (KNU) |

January–March, 1950 | Chinese Kuomintang (KMT) crossed into Burma from China |

February 1951 | Burmese Army and KMT fight |

March 1954 | Thai authorities allowed Karen and Mon rebels to set up camps along Thai border |

January 20, 1956 | cpb indicated it wanted to discuss peace |

June 1956 | U Nu resigned |

March 1, 1957 | U Nu returned as prime minister |

September 26, 1958 | U Nu announced new government led by Ne Win |

October 28, 1958 | Ne Win formed new government |

January 1960 | Ne Win visited China and signed a mutual nonaggression pact |

May 1960 | CPB again indicated it was willing to negotiate |

March 2, 1962 | Ne Win took control and jailed U Nu, as well as Shan and Karenni leaders |

March 3, 1962 | Constitution was suspended, and Parliament was dissolved |

April 1, 1962 | National amnesty provided for all rebels followed by talks with Mon, Chin, Karenni, Kachin, CPB, and Shan |

July 7, 1966 | China indicated its disapproval of Ne Win regime; suspension of aid followed |

January 1, 1968 | CPB launched new attack with Chinese support |

January 15, 1968 | Kachin and CPB leaders agreed to military cooperation |

December 15–18, 1973 | Shan State Army established link with CPB. Both Shan and Karen rebels visited China. |

January 3, 1974 | New constitution adopted without autonomy provisions |

June 29, 1974 | United States and Burma signed antidrug agreement |

November 11–15, 1975 | Ne Win visited China, resulting in nonaggression agreement |

July 5–6, 1976 | Kachin Independence Organization and CPB agreed to end their intergroup conflict. Kachin began purchasing weapons from China. |

February 11, 1978 | Government offensive in Arakan resulted in massive refugee flows into Bangladesh |

Aid agreement between China and Burma announced | |

November 19, 1979 | China reduced its support for cpb |

September 23, 1980 | CPB proposed peace talks |

October 17, 1980 | Peace talks began with Kachin Independence Organization (KIO) |

May 9, 1981 | Government called off talks with KIO |

March 12–18, 1988 | Student unrest in Rangoon |

July 23, 1988 | Ne Win resigned. Sein Lwin takes power. |

August 12, 1988 | Sein Lwin resigned. Replaced by Dr. Maung Maung. Protests continued. |

September 18, 1988 | State Peace and Development Council established |

December 14, 1988 | Thailand and Burma agreed to logging rights |

February 20, 1989 | CPB leaders encouraged to retire in China |

April 17, 1989 | Wa troops captured CPB headquarters |

May 27, 1989 | Burma became Myanmar |

September 2, 1989 | Ceasefire signed with Shan State Army (SSA) |

January 1990 | KIA faction made peace with government |

March 27, 1990 | Pa-O rebels signed agreement with government |

April 21, 1990 | Palaung rebels signed agreement with government |

1994 | Ceasefire agreement with Karenni National Progressive Party |

1995 | KNU headquarters taken by Myanmar Army |

2003 | KNU signed ceasefire with government |

Source: Lintner (1994); UCDP. | |

The groups that make up the armed identity-based conflicts are distinct in culture and language from the politically dominant Burman. While the Panglong Agreement seemed to embrace diversity within the newly forming state, subsequent administrations have either undermined that position or, worse, moved in the direction of attempts at assimilation. President U Nu’s 1960 “Burmanization” campaign, which communicated his intent to make Buddhism the national religion, serves as an example. The Kachin, the leadership of the Karen, and the Muslims in Arakan took exception to this policy. Neither the Karen nor the Arakanese were in any position to escalate conflict at that point, but the Kachin Independence Army (KIA) was formed in response. Despite efforts to force assimilation, changes in cultural identity were slow to occur and certainly were resisted. The region’s colonial and historical background regarding its various identities challenged such a shift even more so. This experience of unfulfilled promises as the country achieved independence has fed into the enduring nature of the conflicts examined here.

The largest, most successful campaigns against the Rangoon government took the form of Communist insurrection. Communism emerged early in Myanmar’s history. After a history of colonial exploitation and animosities over its status relative to India, the independence movement took on a nationalistic fervor aimed at ridding the newly emerging state from external economic intervention (Thompson 1948). As a result, Burma’s revolutionaries (the Anti-Fascist People’s Freedom League, or AFPFL) had leftist-leaning ideologies. The socialist faction of the movement, however, emerged as the country’s leadership upon independence, having expelled the Communist Party of Burma (CPB) in 1946 (Thompson 1948). At this point, the Burmese Communists could have elected to present a united opposition to the AFPFL. Instead, the CPB expelled Thakin Soe, a more radical Communist (Lintner 1994). He went on to set up the Communist Party (Red Flag), which itself supported the Rohingya separatists in the Arakan conflict presented below. Thakin Than Tun emerged as the leader of the CPB, also referred to as the White Flags, a much larger faction. Both groups waged war with the central government of Burma until 1989, when the Communist insurrection disintegrated (UCDP/PRIO 2014) as a result of diminished group capacity. The AFPFL, originally led by revolutionary hero Aung San, included its militia or People’s Volunteer Organization (PVO). A large portion of the PVO emerged as a rebel faction opposed to the new government along with the Red Flags and the larger CPB. All of these organizations together are considered part of the Communist conflict.

The breakup of the CPB resulted in the Wa emerging into their own right with about twelve thousand troops that formed into the United Wa State Army (UCDP/PRIO 2014). The UWSA took over the CPB headquarters at Panghsang and much of the CPB drug trade, including agricultural fields and strategic trade routes. The group was permitted to administer this territory upon the signing of its own ceasefire in 1989 (globalsecurity.org n.d.).

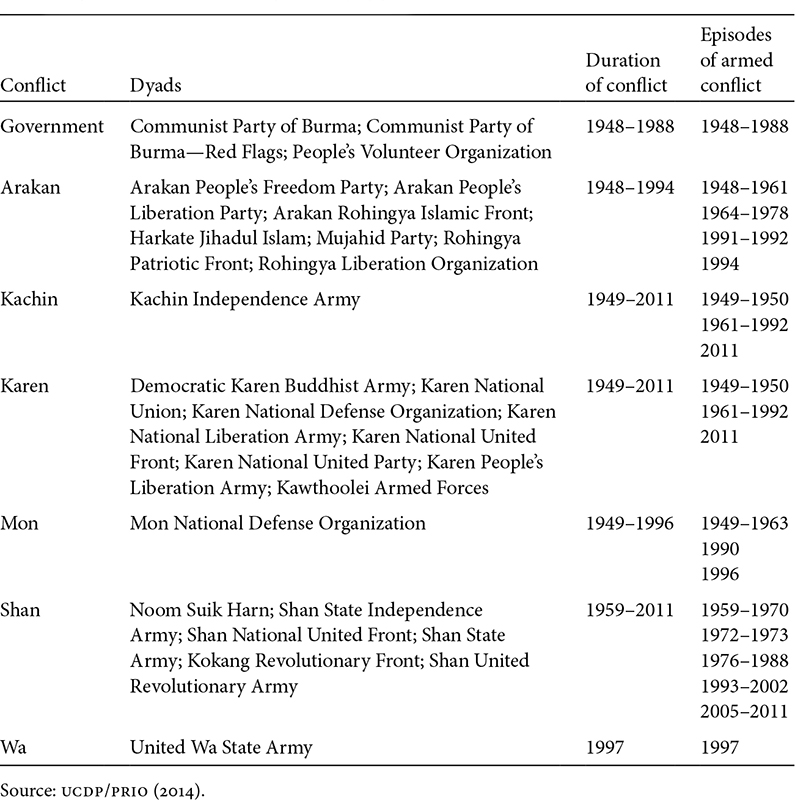

TABLE 5.2 Conflicts in Myanmar, 1948–2011

The remaining conflicts in Myanmar were and are identity-based in nature, although several factions within the conflicts were either sympathizers with the CPB or entered into convenient coalitions with larger, well-connected rebel groups. Armed insurrection by the Arakan and Karenni began almost immediately after independence in 1948, and the following year the Mon and Kachin also rebelled. The most effective of these groups appears to have been the Karen. They are an ethnically distinct group located in the Irrawaddy delta and along eastern Myanmar. The Karen National Union (KNU), and its militia (Karen National Defense Organization, or KNDO), emerged early in the conflict following the massacre of Karen by the pro-Japanese Burma Independence Army, launching its first offensive at independence in 1948 (Lintner 1994). The majority of Karen are Buddhist (60–70 percent), with the remaining members adhering to Christian or animist religions. The rebel leadership, however, was predominantly Christian, which became a factor facilitating group splintering in 1994 and the creation of the Democratic Karen Buddhist Army (DKBA) (Minorities at Risk 2009).

According to its 1949 manifesto, the Karen were waging a war for the right to self-determination, equal rights, and democracy (Rajah 2002). Other Karen insurgent groups include the Karen National United Party (KNUP), the Kawthoolei Armed Forces (KAF), the Karen National United Front (KNUF), the Karen People’s Liberation Army (KPLA), and the Karen National Liberation Army (KNLA) (Lintner 1994). Collectively, these groups comprise the Karen conflict.

Another rivalry that emerged early in Myanmar’s history came from the Arakan State (currently Rakhine) in western Myanmar near the East Pakistan (now Bangladesh) border. The majority of Arakan are Rohingya Muslims of Arab, Persian, and Moorish descent. Their citizenship has been questioned repeatedly by the Rangoon government through several immigration and citizenship laws implemented over time, resulting in various human rights violations (Human Rights Watch 2012). Immigration enforcement in Arakan has involved military operations, mass arrests, and forced relocation. These operations and interethnic violence have resulted in significant refugee flows into Bangladesh. The Rangoon government has also denied the Rohingya property rights, educational opportunities, and more recently, has targeted birth control policies aimed at limiting population growth (Guardian 2015). There were two main rebel groups in the Arakan rivalry: Arakan Rohingya Islamic Front, the more moderate faction, and the Rohingya Solidarity Organization (RSO). The Rohingya Patriotic Front, Rohingya Liberation Army, Arakan People’s Freedom Party (APFP), and the Harkate Jihadul Islam were also active, but smaller in size (Lintner 1992). The Arakan People’s Liberation Party (APLP) was a Buddhist faction that sought independence for Arakan as well.

The Shan rebellion in northeastern Myanmar emerged about ten years after independence. Under the newly independent government, the Shan operated with the understanding that they would be able to secede if they chose to do so after ten years. The Shan share a common religion with the dominant Burman but are culturally and linguistically different (Minorities at Risk 2009). In 1958, the Rangoon government refused to accept Shan secession, which led to the creation of the Noom Suik Harn (Young Warriors) with fewer than 450 men, and began the Shan rivalry with the state. In 1960, the Shan State Independence Army (SSIA) emerged as a splinter group that took refuge in the northern Wa hills and recruited new members (Lintner 1994). The Shan National United Front (SNUF) was also created at this time from the Young Warriors. A coalition was formed in 1964, creating the Shan State Army (SSA), which included the SSIA and SNUF as well as the Kokang Revolutionary Front (KRF), a rebel group from a Chinese-dominated portion of the Shan States. From this coalition, the Shan United Revolutionary Army (SURA) branched into its own splinter faction.

The Chinese Kuomintang (KMT) was also active in Shan territory, although certainly not part of its enduring rivalry. Both the Shan and the KMT, however, found it lucrative to engage in the drug trade, which made for an unfriendly alliance. Interestingly, the Shan also cooperated with the CPB, which allowed them to also receive weapons from China. This decision caused a rift in the Shan rebellion. Although the Shan continued to engage in intrastate warfare, several warlord-type factions emerged, driven more by profit than political concessions (Lintner 1994), including the SURA and the Shan United Army (SUA), which eventually formed a coalition and became the Mong Tai Army (MTA) in 1985 (UCDP/PRIO 2014).

The Kachin are involved in another intrastate conflict in Myanmar. Similar to the Karen, the Kachin are largely Christian and are culturally and linguistically distinct from the Burman majority. They reside in the northern-most territory bordering China and India, distant from the Burmese capital. Economic and insurgency challenges early in Myanmar’s history resulted in underdevelopment and resentment in this region. Following U Nu’s “Burmanization campaign” in 1960, the Kachin Independence Organization and its rebel army, the Kachin Independence Army (KIA) formed. Unlike in other conflicts discussed, the KIA did not experience dramatic intragroup shifts in the form of splintering. It did, however, form a coalition with the CPB. Initially, the two groups fought one another as the CPB extended its influence in northern Burma, but by 1976, the two were working together against their common enemy (UCDP/PRIO 2014). As of the time of writing, the KIA continues to exist and has once again been identified as an insurgent organization by the government of Myanmar (UCDP/PRIO 2014). Fighting continues, but so too are negotiated efforts to resolve the conflict.

Each of the conflicts examined in this chapter is enduring in nature, having engaged in a conflict trajectory that extends over much of the country’s history since independence. The groups identified and described above are by no means the only armed factions or even the only ethnic insurgents operating in Myanmar, however. The Karenni, the Pa-O, the Kokang, and the Lahu are among other smaller groups that have worked alongside those mentioned in opposition to the government. In order to examine the theoretical framework presented, however, analysis is limited to the larger, more persistent conflicts.

Clearly, Myanmar involves a complex set of interactions across a range of actors engaged in a number of armed conflicts. While each of the conflicts examined here has its own conflict trajectories, these histories parallel each other at times and intersect at others. Tactical decisions by armed rebels in Myanmar are similar, however, and are heavily influenced by the same set of factors.

First and foremost, conflicts in Myanmar, whether ideological or ethnic in nature, are heavily influenced by outside actors. At times, countries such as China and Thailand have provided military support, aid, safe havens, and other resources, allowing groups such as the Communist Party of Burma, the Kachin Independence Army, and the Karen National Union to battle the government from a bolstered position. Under such circumstances, it is not surprising that those groups shied away from negotiation tactics, choosing instead to pursue an armed campaign designed to capture territory with the ultimate goal of secession or revolution. When that outside support shifted toward the Myanmar government, the position of these groups faltered. Negotiations were then possible, but with a much improved position for the government. This is evident throughout the conflict progressions presented below.

Some groups in Myanmar relied less on outside support and more on generating their own resources, while others were able to gain from both. Success in controlling drug routes or the ability to sell timber to Thailand gave groups in the Shan, Wa, and Karen conflicts access to resources. While timber trade allowed the Karen to resist negotiation attempts, access to the drug trade led some groups, such as those involved in the Shan and Wa conflicts, to accept the negotiation terms offered by the government in the early 1990s because it allowed them to continue to have access to that stream of revenue and control of the territory.

Myanmar conflicts have also been heavily influenced by intergroup dynamics. When groups such as the CPB and the KIA worked together against the government, both with the support of the Chinese, they were able to make significant progress in gaining territory. In such situations, again, negotiations were much less likely, while guerrilla and conventional warfare were pursued. When those arrangements either collapsed or were torn apart through decreasing outside support, the government was able to take advantage of the situation and target negotiations to one group at a time, thereby turning them against one another.

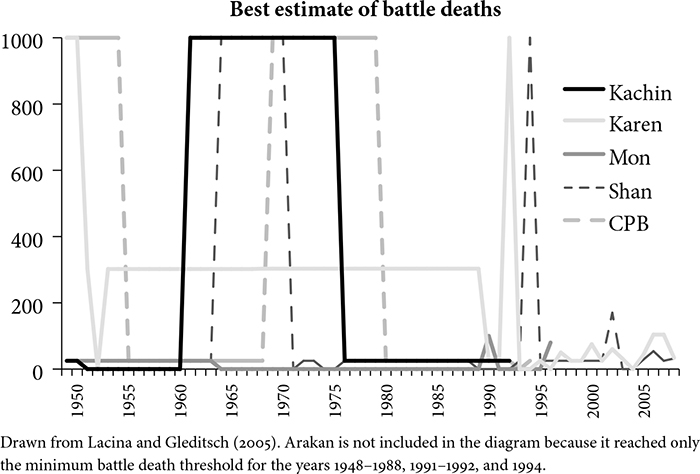

FIGURE 5.2 Patterns of Violence in Myanmar, 1948–2008

What follows is a discussion of the ebbs and flows of both the ideological and ethnic conflicts in Myanmar, illustrating how they unfolded over time and how they interacted with one another.

The Communist insurrection is the only ideological conflict in Myanmar. The expectation is that this type of conflict would be the most threatening to the Rangoon regime and, therefore, the most likely to experience high levels of intensity and sustained violence. It did indeed last forty years. Armed conflict involving various factions of the Communists and the Rangoon government emerged in April 1948 as the government launched a full-scale attack against the rebels from Rangoon to Mandalay (New York Times 1948). The insurrection was undertaken by members who had been a part of the country’s independence movement led by the “30 Comrades.” Not only had they participated in an armed rebellion against a colonial regime, but they were active participants (fighting on behalf of the British) in the Second World War. As a result, the leftist-leaning faction that emerged to become the Communist conflict was well equipped, at least initially, to engage in conventional warfare, which is what it did. When U Nu approached Communist rebels in late 1949 requesting negotiations, the rebels, given their size, responded with an emphatic “no.”

As discussed in chapter 1, the number of rebels that any one conflict can claim is only part of the group capacity picture. It is obvious, having reviewed the number of armed factions present in Myanmar’s history, that the cohesiveness of groups is also likely to influence their capabilities vis-à-vis the government. The message delivered to U Nu in early 1950 came from a unified force, as the various factions of Communist insurgents had met and responded as one. According to Lintner (1994), by 1950, the CPB claimed 15,000–18,000 fighters, plus an additional 1,500–2,000 Red Flags and 4,000 from PVO. Comparatively, U Nu’s military had experienced significant defection as it was split along both ideological and ethnic lines. Defection levels for the Burmese military were to the point that the CPB had a clear advantage. U Nu’s decision to seek negotiations made sense in light of this information. The unified Communist insurgency in the form of the People’s Democratic Front (PDF) was short lived, however, and the tide began to turn in 1950. Amid a fractured PDF, the Burmese army that had been ravaged by mutiny was able to rebuild with massive assistance from neighboring India. This began a general theme in Burmese conflict history whereby escalation and de-escalation are closely linked to external support and the extent to which weapons were available. Early insurrections by the CPB, KNU, and others were made possible by weapons in the countryside that had been used to fight Japanese forces in World War II (Lintner 1994). This fact, along with the diminished capacity of the newly formed Burma military, allowed the CPB and KNU to make early advances. Those weapons, however, were either used up or required new ammunition over time, forcing rebels to capture weaponry in battle, which both groups were able to do at times, or seek outside support. The government, on the other hand, was able to make up through requests for outside assistance what it lacked in personnel and equipment. In 1950 the lack of progress for both the CPB and KNU rivalries was largely accounted for by the decisions of outside actors to supply the Burmese army (Lintner 1994).

The Rangoon government was the beneficiary at this time. Support from India was followed by military assistance from the United Kingdom and the United States in response to their larger regional concerns. Just when the Communist insurgency was experiencing its second bout of splintering, the government was consolidating. By the end of 1950, in a little less than a year, Rangoon was able to reestablish control over all towns seized by the Communist groups in the previous two years (Lintner 1994), creating a lull in the previously hot conflict that lasted until 1968. The Communists were certainly not defeated, but their effectiveness waned.

In 1953, the dominant Communist faction, the CPB, reached out for external assistance. The Communist revolution in China had succeeded, resulting in the fleeing Kuomintang taking up residence in northeastern Burma. The CPB sought assistance from China while, interestingly, offering to combine forces with Rangoon to defeat the KMT rebels (Lintner 1994). Both requests fell on deaf ears, although China was indeed sympathetic to the CPB’S cause. At the time, however, the Chinese were not willing to risk alienating the Burmese government, which itself was battling the KMT.

The CPB shrunk significantly following government successes through the late 1950s and 1960s. However, the New Year’s Day offensive in 1968, which was launched by the CPB from China, brought about a period of relative strength for the CPB, where it effectively gained control over most of northeastern Burma, including the Wa hills. The capacity of the CPB at this time included twenty-three thousand armed rebels. It was at this time that the Wa were incorporated into the CPB army (UCDP/PRIO 2014).

China made the decision to provide aid, weaponry, and training to the CPB in 1968, which led to the CPB offensive that proved successful until the Chinese again changed their view and policy regarding Burma. In the meantime, the new capacity of the CPB allowed them to challenge the Rangoon government successfully, to the extent that by the mid-1970s they controlled a twenty-thousand-square-kilometer section of northeastern Burma (Lintner 1994). Further, China was also willing to provide weapons to other groups, including the Kachin, as long as they recognized the CPB as the dominant insurgent group. Failing to make progress in northeastern Burma given the renewed strength of the CPB and its allies, the government shifted its attention to the floundering Red Flags in the Irrawaddy delta in 1970. Government troops forced the Red Flags to withdraw in 1975 (UCDP/PRIO 2014).

Rangoon, having experienced its earlier bout of military defection, worked to consolidate and grow its forces as well. In the mid-1970s, there was a rumored division within the armed forces of Burma between those operating against the ethnic insurgents in the frontier regions (led by General Tin U) and those operating in and around Rangoon. As a result, Ne Win purged the military of the pro–Tin U supporters, effectively consolidating the military and its loyalty even further (Lintner 1990; Maung 1990; Silverstein 1997; Schock 1999). In 1991, it appeared that Ne Win once again had some concerns over the loyalty of his military, resulting in orders to “shoot deserters on the spot” (Lintner 1991). This order came at a time when the government was engaged frequently with ethnic rebels and among some reports that local militias had joined the insurgencies (Lintner 1991). The Rangoon government also formed local militias, called the Ka Kwe Ye (KKY) or “home guards,” to increase its numbers. The first KKY was set up in 1963 to combat the Shan (C. Brown 1999). In addition, the military had grown in size dramatically over time and became more pervasive in Burmese society (Lintner 1994). In the period following the pro-democracy movement, the army had grown to twice its earlier size, approximately 380,000 (Economist 2005). This, coupled with the junta’s willingness to sacrifice civilians in its campaign against ethnic rebels, brought many groups engaged in armed conflict to accept ceasefires even without political concessions.

In 1979, the CPB was forced to find other avenues of funding when the Chinese decided to decrease their aid and assistance. This led the CPB to also take advantage of the lucrative opium trade, as their territory accounted for a significant amount of the opium fields (C. Brown 1999). Earlier CPB leadership had been against participating in the drug trade. The assistance of China was further reduced in the late 1980s. With the Burmese government courting investors and providing access to resources, China was anxious to take part. As a result, the CPB and Kachin leaders were pressured by their former financiers to retire to the Yunnan province inside Chinese borders. A CPB ceasefire with Rangoon was finally reached in 1989. This prompted the Kachin to follow suit, but not until a June 1992 Kachin offensive into northwest Burma had failed (Lintner 1993). With a significant loss in group capacity, both the CPB and Kachin were brought to the table. No political concessions were offered, but the offensive against them stopped.

The 1979 shift in Chinese policy resulted in a de-escalatory phase for the CPB, bringing about what appeared to be the ultimate termination of the conflict in 1989. A short-lived Communist-inspired All Burma Student’s Democratic Front (ABSDF) took up arms against the government following nonviolent demonstrations in 1988 that resulted in government repression,2 but this armed conflict with the government was terminated as many of their collaborators began negotiating agreements with the State Law and Order Restoration Council (SLORC).

The UWSA also claimed large numbers, having emerged from the CPB. According to the Wall Street Journal (2010), the Wa have a private army of as many as twenty thousand. The UWSA was able to take advantage of the splintering and then the demise of the CPB, as well as the surrender of the drug lord Khun Sa (Shan United Army), and expanded its operations (Cornwell 2005). The Communist armed rivalry may be terminated, but Wa activity continues.

Despite theoretical expectations, ethnic conflicts have been long in duration and equally intense at times. Although the government has not been engaged in a battle for its survival (the only exception being the Karen’s unsuccessful push toward Rangoon early in its conflict), it is clear that the animosities between various ethnic insurgents, the Karen and Rohingya (discussed further below) in particular, served as fuel for the fire. The military’s willingness to target civilians as a tactical choice has demonstrated such. The length of these rebellions in light of the nature of the conflicts can also be attributed to the country’s terrain, which was addressed previously. Each of these ethnic insurrections was able to take advantage of the mountainous and jungle terrain that they call home. Karen. The Karen National United Party emerged in the delta working closely with the CPB, sharing the Rangoon government as a common enemy (UCDP/ PRIO 2014). The first period of escalation coincided with that of the CPB and Red Flags in a display of intergroup collaboration, where they effectively took over parts of eastern and central Burma where much of the Karen population lived. The KNDO, which also gained experience fighting in World War II, began with the same conventional warfare approach as the CPB but shifted to guerrilla warfare after losing a May 1949 battle over Insein (Lintner 1994). Following a few years of heavy fighting, a lull emerged until 1955, when the KNU of eastern Burma experienced a renewed campaign by Rangoon against their remaining strongholds (Lintner 1994). By 1956, it appeared the Karen were close to defeat along with the CPB, although it was at this point that the Karen (and the Mon) were able to establish rebel camps in neighboring Thailand. The conflict continued, however, and escalated again in 1971 as the KNUP, an armed faction within the Karen conflict, cooperated with the CPB. With the conclusion of the Communist hold in the delta in 1975, the KNUP was forced to reunite with its KNU counterparts in the east.

A subsequent government offensive in early 1984 led to another period of escalation for the Karen conflict (Lintner 1994). What followed was a series of government offensives, with the army capturing more Karen territory. The Myanmar offensive against the Karen began in 1989 and brought about the fall of Manerplaw (Rajah 2002). Fighting between ethnic insurgents and the Rangoon government was the norm during 1991. Pursuing rebels gave the government something of a diversion from repressing political dissent in Rangoon and elsewhere. What seemed to have shifted at the time, however, was the location of fighting, which was taking place in the Irrawaddy delta (ironically, where much of the fighting took place early in the CPB and Karen conflicts), not in the border areas (Lintner 1991). This shift was the result of a Karen offensive to break out of their limited Manerplaw stronghold and extend their influence west toward Rangoon.

In 2004, the KNU was engaged in discussions with General Khin Nyunt, preparing to settle on a ceasefire arrangement. He was relieved of his duties at that time (which appeared to be the result of division within the government), and the KNU returned home (Economist 2004). Conflict escalated dramatically around 2005 when the military moved the capital to Pyinmana (Mullany et al. 2008), and the SLORC began a violent campaign of forced removal of Karen from eastern Burma (Human Rights Watch 2005).

The KNDO, KNU’S militia, boasted large numbers as well (nearly twelve thousand in the early 1950s according to Lintner [1994]). It too began with conventional warfare and, for the same reason, moved to embrace guerrilla warfare around the same time as the CPB, although not entirely. Having once established a base of operations in Manerplaw, they continued to employ conventional warfare tactics until the fall of that base in 1992 (Rajah 2002). As one of the last ceasefire holdout groups, the Karen were able to draw popular support from the civilian Karen population, numbering 2,122,825 (6.2 percent of the total population), according to the government’s 1983 census (Silverstein 1997).3

The cohesiveness of the Karen, or lack thereof at times, had also impacted the conflict and its progression. Although several Karen groups emerged early in its history, particularly as the Karen resistance was split between those in the eastern hills and those in the Irrawaddy delta, the factions continued to collaborate against the central government. This geographic split, later involving a political orientation division as well, meant that the government could focus in either one direction or the other. In other words, the Karen power in numbers was indeed diminished because the force was not concentrated. This is what the government did when it focused on the Karen in the Irrawaddy delta (along with the Red Flags) in the early 1970s. The KNU forces were compelled to flee and join their KNU counterparts in 1975.

A more significant splinter, however, occurred when the Buddhist elements in the KNU perceived their Christian leadership as unrepresentative of all Karen and defected to the Burma military following a decision to build sacred sites, pagodas in particular, in Karen-held territory (Hayami 2011). Later this group created the DKBA (1994), which agreed to a ceasefire with Rangoon the following year. Before this, however, the Buddhist Karen led the Myanmar military through the minefields surrounding Manerplaw, leading to its fall (Rajah 2002). After the ceasefire of 1995, the DKBA also aligned itself with Rangoon and actually took up arms against their Karen brothers of the KNU.

In addition, the inability of the central government to control the frontier areas allowed insurgents to set up tollgates gathering revenue by taxing trade on jade, teak, and opium, among other resources (Ballentine and Nitzschke 2003). As mentioned, the drug trade has been a significant revenue generator for many rebel groups. Although the KNU did not participate in the drug trade (Grundy-Warr 1993), the Shan and the Wa did. The ability to participate in the drug trade within the Golden Triangle has allowed rebel groups to purchase weapons to continue their conflicts, but it has also created divergent interests. Khun Sa, for example, reached the top of the wanted list of the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) for his participation in the drug trade. Although the SUA, Khun Sa’s Shan United Army, had the appearance of an insurgent group in pursuit of political goals, the interests of Khun Sa and those around him became increasingly led by the motive to increase profits (Cornwell 2005). Several of the armed conflicts have been transformed in this regard with insurgent armies, warlords, and the state benefiting from continued violence (C. Brown 1999).

Myanmar has been the benefactor of outside assistance many times through its history (Holliday 2005). Often this assistance has come at crucial times. This occurred early on with India, but also more recently in the post-1988 election debacle.4 Trade and support from its regional partners provided the central government with the resources it needed to continue to repress dissent and wage warfare against those groups that have fought ceasefire arrangements. The recent development of a pipeline from Arakan through Myanmar to China’s Yunnan province is expected to provide the Myanmar military with at least $29 billion over the next thirty years (Jagan 2009). It has also benefited the government in that it drew China’s support of a UN Security Council veto of a measure that would have required the country to release all political prisoners, engage in dialogue, and end widespread human rights abuses (UN News Centre 2007). The Myanmar army continues to receive and purchase weapons from China, Russia, Ukraine, and Singapore (Jane’s 2012), which has allowed the army to increase its capacity.

The 1989 timber agreement between Burma and Thailand was a serious blow to the KNU rebels, who had been operating in the previously rebel-friendly Thailand (Grundy-Warr 1993). The Karen and Mon (a conflict not covered here) had been able to operate from bases in Thailand and purchase weapons since 1953, which had dramatically increased their capacity. While Thailand continued to push its neighbor to come to talks with the rebels because of its history with these groups, the change in policy also gave permission for the Burmese army to pursue those rebels across the border. Thailand further moved to assist its neighbor in 2003 with the repatriating of refugees and illegal immigrants in an agreement that also promoted cooperative trade and drug eradication activities (Yin Hlaing 2004).

Because of the resource opportunities and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) policy of constructive engagement (Holliday 2005; Economist 1992), the SLORC named Thailand, China, Pakistan, and Singapore as its supporters. Even Japan, which originally suspended aid in light of the 1988 uprising, refused to join in the Western boycott because of its interests in the country (Schock 1999). Demonstrating that this support has changed over time, however, both Thailand and China helped to foment rebellion in Myanmar with the arming of rebel factions and providing safe havens at earlier times. When they did so, those rebellions did well. A shift in their policy and their alliances changed the trajectory of those conflicts significantly.

Arakan. An additional conflict was initiated in western Myanmar, by the Arakan People’s Liberation Party but joined by the Mujahid rebellion in 1948. The groups worked closely with the Red Flags, although that group was itself the smaller of the Communist factions. The groups did well early on in their campaign. By August of that year, the Rangoon government could claim very little territory in the western region bordering Bangladesh (UCDP/PRIO 2014). However, most of the territory in northern Arakan was recaptured as the numbers of Mujahid dwindled from several thousand in 1948 to “just a handful” in 1950 (Lintner 1994). For the most part, the rivalry seemed to enter a lull at this time, although in 1954 some political concessions had been offered (Lintner 1994), suggesting that resolution might have been possible. One-sided violence reignited, however, in 1978, when the government initiated Operation Naga Min, a massive offensive effort to identify illegal immigrants (Kamaluddin 1992). The government effort caused more than two hundred thousand refugees to flee to Bangladesh (UCDP/PRIO 2014; Lintner 1994). The implementation of a citizenship law in 1981–1982 also contributed to the flight of people across the border (Minorities at Risk 2009). The mass exodus of refugees brought international attention and ultimately forced the Rangoon government to repatriate the refugees following negotiations with Bangladesh. A similar exodus occurred in 1992 following a renewed operation in Arakan by the Myanmar military.

In 1989, the Rohingya were permitted to form political parties and managed to get four members elected. That permission was revoked by General Ne Win in 1991, however, and two of those elected were arrested and tortured (Silverstein 1997). More recently, intercommunal violence and government policies have resulted in Rohingya fleeing or being forcibly removed from their homes. With Bangladesh and other regional states unwilling to allow for the same mass of refugees as in the past, Rohingya were confined to makeshift camps with little to no resources or have taken to makeshift boats in the hope of finding sanctuary, generating large-scale humanitarian crises in the process (Atlantic 2015). The armed conflict that existed early in Burmese history has been in large part replaced by one-sided violence by the government and communal violence between the generally Buddhist Rakhine and the predominantly Muslim Rohingya.

The original armed insurrection led by the APLP involved some two thousand rebels who worked closely with the Red Flag portion of the Communist rivalry. This allowed them to do well in their war against the government early on, but their numbers could not withstand government offensives. As a result, the rivalry was one of fairly low intensity, with the rebels unable to sustain their efforts much beyond 1978. Compared to other conflicts examined here, the Rohingya have been unorganized and lack international networks to bolster their position vis-à-vis the government (Parnini 2013). Further, the level of one-sided and communal violence was notably pronounced in this case. Although the Myanmar government has been quick to accept civilian casualties in its campaign against ethnic insurgents throughout the country, that is particularly the case in the Arakan conflict. The animosity many Burman feel toward the Rohingya helps explain the brutal nature of the interactions between the government and the Rohingya people of Arakan State. Rohingya are frequently referred to as Bengali, which suggests that they are seen as primarily recent refugees from Bangladesh rather than long-term residents of Myanmar, which has led to the types of exclusionary policies identified above. These views are exacerbated by concerns that the Muslim community is growing too quickly and “threatening to take over” (Guardian 2015). Not surprisingly, this is the only conflict examined that did not involve some form of negotiated outcome in the late 1980s, despite the brief permission for Rohingya political parties. Much of the armed aspect of this conflict had been replaced by repression and intercommunal tension, although the Arakan Army continues to operate amid the instability. As of 2016, the Myanmar government has vowed to eliminate the group (Radio Free Asia 2016).

Shan. The Shan rivalry emerged later than those examined above because they had been promised a referendum on independence ten years following statehood. When that did not happen as expected, armed rivalry emerged. The Shan benefited from large numbers and significant demographic support. Although the Shan rebellion did not emerge until 1958, they were five to six thousand strong in the 1970s. They also benefited from a Shan population of nearly three million (as of 1983) (Silverstein 1997). Their numbers had increased dramatically through collaboration with the MTA (although its leader, Khun Sa, was ex-KMT). The MTA claimed between eighteen and twenty thousand members (Lintner 1994). The capacity of the Shan had been diminished, however, with the splintering of groups and its participation in the drug trade, which is ironic given that the revenues generated in the trade also increased its capacity in another regard. The splinter factions of the Shan have not always cooperated and, in fact, have fought one another at times, particularly when some of these groups became more defined by the drug trade and their profit motive than their desire for independence or autonomy. The ceasefire and surrender of some groups, such as the SSA and the MTA, was made possible because the government allowed these groups or their leadership to continue to engage in such business ventures.

When the CPB disintegrated, many Shan factions signed ceasefire agreements or joined the MTA. By late 1995, the Shan State National Army (SSNA) and even Khun Sa of the MTA were forced to negotiate a ceasefire with the government. The splinter SSA-South continued the fight, however, and proved to be fairly effective in gaining control of several areas of the Shan States (UCDP/PRIO 2014).

Kachin. The success of the Kachin insurrection can also be attributed to its links with the CPB. The KIA was composed of six to seven thousand members by the early 1990s (UCDP/PRIO 2014). As indicated earlier, it was also a cohesive unit. Although the Kachin population was only approximately 1.4 percent (Silverstein 1997), splintering was not evident in its history. They are located in the far reaches of northern Burma, making it a challenge to reach them for the Myanmar army. The length of the Kachin conflict can be explained in large part by its location and its close cooperation with the CPB. After its emergence and coalition with the CPB, the trajectory of the KIA mirrored that of the Communist conflict, with a ceasefire reached in 1993. The ceasefire agreement with the KIA collapsed in 2011 over exploitation and the forced displacement of Kachin surrounding the Chinese Myitson Dam project. However, the KIA and Myanmar government continued to engage in dialogue over the dispute.

The Panglong Agreement could have paved the way for a more inclusive, less violent Burma. That agreement was abandoned, however, leaving the lasting impression that the government could not be trusted, which explains why groups held on to secessionist and autonomy goals. As discussed earlier, the goals of ethnic rebels in Myanmar began with calls for independence and the right to determine their own governments. Early success by the Karen, coupled with behavior of the Rangoon government toward the Karen insurgents and civilians, left them clinging to the hope they could achieve at least some political autonomy. For the most part, rebels in Myanmar refrained from employing terrorist tactics, with only a few exceptions (kidnappings in 1975 by the KIA and 1983 by the KNU, for example). Terrain in this case made for lengthier conflicts as groups were effectively able to evade capture or defeat over long periods of time. As the conflicts endured, and victory remained elusive, groups were more willing to accept autonomy instead of independence. These shifts in group goals made negotiation a more likely scenario. Negotiations did indeed occur with the CPB, Red Flags, Karen, Mon, Shan, and Kachin rebel armies in 1963 (Lintner 1994). The government, not surprisingly given its position vis-à-vis its rivals at the time, was unwilling to provide political concessions and set the precedent that it would provide concessions. It was, however, willing to discuss these groups’ surrender. This pattern was repeated time and again. It was not until group capacity waned in relation to the government’s, along with the promise that groups could maintain some of their territories and privileges within, that ceasefires emerged.

Intrastate conflicts in Myanmar have been dominated by guerrilla warfare on the part of the rebels and repression on the part of the government, coupled with calls for outside assistance to continue the fight. For the rebels, pursuing guerrilla warfare as a tactic allowed them to survive even as the Myanmar military became larger. The government, for its part, continues to employ repression because this tactic keeps it in power. Its approach, as a result, was consistent, and it increased in intensity over time. In the mid-1960s, the government began to implement the “Four Cuts” approach to dealing with its ethnic rivals. The military worked to cut off the supply of food, funding, information, and recruits to the rebels. “Free fire” zones were also established in areas heavily populated with Karen, Karenni, and Mon. The policy forced villagers into the jungles, becoming internally displaced (Lee et al. 2006). The Four Cuts policy continued to foment anger and mistrust among Myanmar’s minority groups, as it confirmed once again that civilians were fair game. It also communicated to the rebels that the government was perfectly willing to target civilians to achieve its goals.

The Four Cuts policy failed to defeat Myanmar’s intrastate armed factions completely. As a result, a new phase of the policy emerged in 1989. The military regime encouraged ceasefire agreements with insurgents using a carrot-and-stick approach. If groups were willing to agree to a ceasefire, insurgent leaders were provided business concessions allowing them to benefit from trade in their area (legally), or the government would tolerate their participation in the opium trade (Ballentine and Nitzschke 2003). Agreeing to those concessions meant they were also aligning themselves with the central government in opposition to insurgents who continued the fight. Refusing to come to ceasefire terms would mean extra pressure would be placed on that group’s civilian population (Silverstein 1997). The goal of this approach was to lessen the number of active armed dyads for the government, as well as reduce the chances of rebel group coalitions forming. When the government adopted this policy, fifteen insurgent groups accepted the ceasefire (Silverstein 1997). During these ceasefire discussions, political concessions were not on the table, but the promise to participate in a national convention was. These promises have yet to amount to much. As a result, subsequent negotiations followed, including the October 2015 Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement (NCA) involving half of the country’s rebel factions. Those that did not sign the agreement called for the government to end its military offensives and create “good opportunities for national reconciliation” (Radio Free Asia 2015).

Myanmar clearly involves a complex set of armed conflicts that have changed significantly over time. The theoretical framework put forth has proved to be an effective tool for understanding how and why they have changed in the way they have. Static factors, such as terrain, cultural aspects, and historical experiences, have created an environment conducive to guerrilla warfare that can persist, despite the increasingly repressive tactics employed by the government. It is also evident that the capacity of groups relative to that of the government has influenced conflict trajectory. When groups benefited from large numbers in comparison to those of the government, they were able to do well on the battlefield. When outside assistance was provided, it allowed groups to survive and sometimes flourish, even when a growing military was on the offensive, as did intergroup collaborations. When the tide of outside intervention shifted, however, insurgencies were diminished and intergroup fighting emerged.

Rebel groups’ capacities have been significantly influenced and improved through intergroup collaboration to an extent not seen in any of the other cases examined here. Although coalitions did form in the Republic of the Congo, the extensive sharing of resources, collaboration in battle, and the merging of groups into larger entities appears unprecedented. This allowed smaller groups to persist and larger groups to expand. In fact, despite the number of conflicts that existed and the divergent number of issues involved, intergroup collaboration was the norm, and intergroup conflict was fairly uncommon early in the Myanmar conflict histories. This changed, however, when the government actively pursued eliminating rivals through its Four Cuts policy. By breaking down intergroup collaboration, actively pursuing groups, promising economic opportunity to group leaders, and limiting external support to rivals, the government was effectively able to decrease the number of active armed conflicts that existed. Of course, the democratization movement emerged during this time, which served to perpetuate violence in Myanmar.