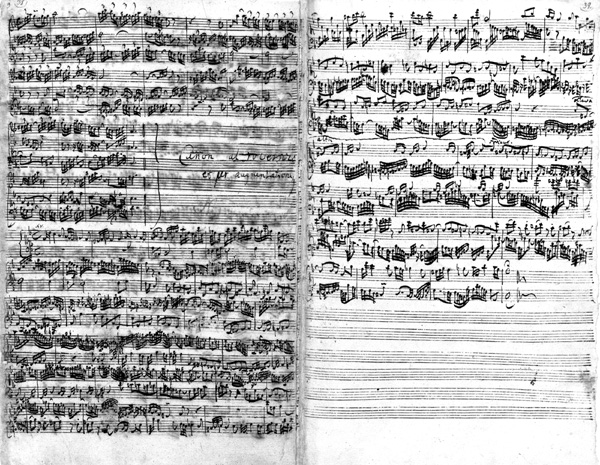

There are reasons to suggest that the jammed writing in the first half of canon xv was intended to fit it into a given page space (Figure 9.1). Since this is a bipartite canon, its second half should be equal to the first in length, and since the first half occupied less than 12 staves, the whole canon could fit into 24 staves. That succeeding, and assuming that page 39 and page 40 would each be rastered with 24 staves, Bach might still have had at his disposal 36 blank staves. What would these staves be intended for?

The most likely candidate among the pieces composed around this same time is the mirror fugue for two claviers. Indeed, each of its two components, written on P 200/1–2—the fuga recta and the fuga inversa—occupies exactly 36 staves. It very well may be that Bach planned to write on the available staves so that the fuga recta would end at the bottom of page 40. Its mirror, the fuga inversa, should begin on page 41, for which manuscript paper would be added.

To consider how many additional manuscript papers were needed, certain information has to be taken into account. A substantial part of Bach studies devoted to his creative process emphasises the careful attention that the composer paid to the organisation of pieces in his composition collections. He regarded as important not only the musical and rational aspects of these works, but also the physical organisation of its material embodiment.

Pairing was an important structural principle in Bach’s collections and cycles, and no less so in The Art of Fugue, where it is expressed by a sequence of fugue pairs. Schemes 7.1 and 7.2 show how the same principle was applied to the binio-structure of the Autograph’s main body. Since it was Bach who chose this particular combination of bifolios,1 it would be reasonable to assume that he would proceed with the same structural principle and add one more binio, that would result in pages 41–8.

It is also likely that Bach would retain his approach concerning the fugues, and since the pairing principle lies at the core of The Art of Fugue, he would probably add a pair of fugues rather than just one. In this case the first fugue was written for two claviers. Therefore, another fugue of the same type was to be expected. According to this way of thinking, Scheme 9.1 would describe the assumed last two binios with their additional pieces and Scheme 9.2—the whole Autograph’s hypothetical new plan.

This plan is, of course, just a hypothesis of a possible structure. Its only trace in the Autograph is the exceptionally crammed writing of the first half of canon XV and the assumption that it was written like that in order to fit it all into 24 staves, so that the remaining 36 staves would be available for the next planned piece.

This plan did not materialise; the second half of canon XV is so clearly written in a flowing, relaxed notation, occupying 14 rather than 12 staves, that clearly the intention to leave space for another fugue was abandoned.2 This probably happened sometime in mid-realisation, and likely for a new compositional idea, so clear and evident in the structural plan, that Bach surely had noticed it.

Schemes 9.3 and 9.4 show how the cycle might have looked after adding the pair of mirror fugues for two claviers. The pieces of the cycle are numbered in the schemes in Roman numerals from I to XV, just like in the Autograph. Three additional numbers—those related to hypothetical insertions—are printed in italics: xvi, xvii and xviii.

Number xvi was assigned to the extant fugue for two claviers, (P 200/1–2). It is marked in italics because in the manuscript it does not carry a serial number. This fugue would follow the canon XV, and it is possible that Bach had planned for it the space of 36 staves in the manuscript.

The second number in italics, xvii, indicates a hypothetical second mirror fugue for two claviers that, presumably, would have paired with the extant fugue xvi.

Number xviii indicates a canon that, following the logic of The Art of Fugue and of several other Bach’s cycles, would seal the whole work. The numbers that are boxed in Scheme 9.3 indicate canons (marked C1, C2, C3 and C4, referring respectively to canons IX, XII, XV and xviii). The first three canons exist in the Autograph under the very same numeration that appears in the scheme. The fourth is assumed, based on Bach’s habit to cap a cycle with a canon.

Does this hypothetical canon actually exist?

Yes, most probably so. The compositional approach detected in canons XII and XV is consistent: Bach starts to correct the proposta of a completed piece but does not transfer the corrections into the risposta. Once the melodies of the proposta and risposta are not identical, the work becomes a draft for a new composition. Thus, the corrections made in canon XII are realised in canon XV, and those marked in the proposta of canon XV would be realised in both proposta and risposta of canon xviii.

Such a correction does exist. It appears in P 200/1–1 and is titled Canon p[er]. Augmentationem contrario motu.3 The fact that this supplement is a canon reinforces the assumption that it was planned as the closing piece of the cycle.

In this new version of the canon Bach continued to develop the corrections even further. What started as a ‘memo annotation’ in bar 11 of canon XV developed into its realisation in the canon P 200/1–1, proposed here as the planned canon xviii.4

In canon xv this correction was marked only in the proposta. In P 200/1–1, on the other hand, the correction appears in both the proposta and the risposta, albeit in a more elaborated variant. Example 9.1 shows the development of this elaboration. For the sake of clarity, the example shows the motif in P 200/1–1 twice: once preserving the rhythmic values of canon XV and once as it appears in the supplement.

It therefore looks most probable that the canon tentatively marked in Scheme 9.3 as number xviii is actually the one written on P 200/1–1, where it appears as an engraver copy. If, indeed, once becoming ‘drafts’ the canons marked as XII and XV should not be present in the final work, then the structure of the cycle might be as the one shown in Scheme 9.4. The scheme looks like a simple development of the Second Version. However, the composition described in it does not exist in actuality. In the Autograph, canons XII and XV are present, making The Art of Fugue a composition that is both finalised and in the process of becoming.

This scheme presents an image that could not have escaped Bach’s attention and which, by providing him with a vision of the final version of The Art of Fugue, did motivate him to realise it. Entering the mind of a composer without a factual verification is indeed adventurous, but in order to better understand this masterpiece, it is imperative to conceive what could be the general scheme that the composer had in mind while planning the next stage of the cycle’s composition.

One significant trait of Bach’s multi-partite cycles, especially those consisting of pieces of one type, is their clear tendency to subdivide into two groups, which in a certain sense can be interpreted as pairing on a higher level.5 This type of subdivision exists in the Inventions and Sinfonias, the Goldberg Variations, the Clavierübung III and the Canonic Variations, to name just a few.

Such a division is apparent even in the sheer physical appearance of the planned Autograph; as Scheme 9.2 shows, the expanded manuscript would consist of 12 bifolios, which symmetrically divided the content into two equal parts of six bifolios each. The first part, ending with canon IX, would reflect the earlier First Version; while the second group of bifolios, all on newer paper, would be the result of later thought. The division of six plus six, whether coincidental or planned, had special significance for Bach.6

Further, like in others of his bi-partite works, here, too, the second half seems also to reflect a possible realisation of the ascending principle (Steigerungsprinzip). Presenting two double fugues and the two mirror fugues for two claviers, it would include compositions that are more complicated than the fugues in the first half, which are relatively simpler.

The number of fugues in each part is significant. Here, however, the division would not be symmetrical, showing eight fugues in the first part and only six in the second. On top of that, Scheme 9.3 shows a first part capped with one canon, while the second seems to include three other canons spread throughout it. However, one should bear in mind that two of the dash-framed canons shown in Scheme 9.3 cannot really partake in the same structure. The last three canons (XII, XV and possibly XVIII, which could be the canon of P 200/1–1) are based on one and the same theme: there should be, in fact, just one canon. Following Bach’s use of canons to mark the completion of a group of fugues, one would tend to opt for Scheme 9.4 as a more likely structure, featuring only canons IX and XVIII.

Alternatively, another possible plan could, in fact, include the four canons. The work now consisted of 14 compositions, the numerical symbol of Bach’s name, a number to which he persistently adhered throughout his work on the various versions of The Art of Fugue. These 14 compositions, reflecting both the pairing principle and the symbolically significant numeral 7, might allow a double organisation: seven pairs on one hand, and one meta-pair of two groups of seven fugues on the other (both 7 × 2 and 2 × 7). Moreover, the number 7 itself, following Bach’s system of numerical signification, should be divided into 4 + 3,7 which is exactly the division of pairs shown in Scheme 9.4: four pairs of fugues, capped by canon IX, and three pairs of fugues, capped by a final canon XVIII.

A division of the 14 fugues into two groups of seven each, however, presents a completely new structure (Scheme 9.5).

The special symbolic significance that is imbued in seeing the number 14 as a combination of (4 + 3) + (4 + 3) may have been the reason for which Bach considered this particular structure.8

The thought of a meta-structure might have led Bach to yet another idea, that of a ‘meta-fugue’, in which the individual fugues may be seen as statements and the canons as episodes.9 To actualise such an interpretation, Bach would need to compose one more fugue that would provide an appropriate closure to the whole structure. Eventually, he would do so.

The particulars mentioned here support the view that at the moment in which Bach settled in to write a Third Version, he also decided to abandon the plan to seal the work with the two mirror fugues for two claviers. Therefore, there was no more need of condensed writing in order to save space for another fugue (xvi) that would follow the canon, nor to compose yet one more (xvii) as its pair.10 Bach completed the canon with no further plans to add a fugue on that page, eventually recording the fugue on a separate bifolio, which is now known as P 200/1–2.11

The new composition required both new structure and new pieces, which would form the Third Version of The Art of Fugue.

1 For example, in the Mass in B minor Bach uses the sequence of 12 binios (12 × 2) for the Kyrie, while in the Symbolum Nicenum he combines three quarternio (3 × 4), although he could continue with the same structure as before. These preferences reflect numerical symbolism to which Bach attached particular importance.

2 The music is inscribed on this page with less attention to graphic density, and written more quickly than on page 38. The rastration on this page was done more hastily, too: the staves were drawn in a less accurate way, and their number—20 instead of 24 in the former page, drawn with no particular calculation—implies, too, that Bach abandoned his previous plan.

5 See Kira Yuzhak, ‘O prodvigayushchey i svertyvayushchey tendentsiakh v Iskusstve fugi: “Alio Modo” i parnost’ vysshego poryadka’ [Expanding and contracting tendencies in The Art of Fuge: “Alio Modo” and the pairing of the highest order], in K. Yuzhak, Polifoniya i kontrapunkt. vol. 1, (St Petersburg, 2006), pp. 165–94.

6 Quite often Bach organises compositions within his collections or cycles in groups of six. This is not coincidental or whimsical. One of the many reasons that this number was chosen is that it was the first of the so-called perfect numbers (perfectus primus). Another reason is that it rounds the first number series in the senary numerical system; besides, it also has a special symbolic significance in the Pythagorean system of thought, admired by the Society of Music Sciences members. Finally, its combinatorial properties and convenience in modeling a composition (3 × 2 or 2 × 3, that is, the organisation of three two-piece pairs or one ‘meta-pair’ with three pieces in each) provided flexible opportunities of compositional organisation. For a more detailed account see Anatoly Milka, ‘Bakhovskie “shestërki”: Printsip organizatsii bakhovskikh sbornikov v kontekste osobennostei barokko’ [Bach’s ‘cycles of six’: the organisation principle of Bach’s collections in the context of baroque characteristics], in Muzykal’naya kommunikatsia, Seria Problemy muzykoznaniia, vol. 8, (St Petersburg, 1999), pp. 220–38.

7 The first to present such structure was Olga Kurtch, ‘Ot pomet kopiistov—k strukture tsikla Iskusstvo fugi’ [From scribes’ annotations—to the structure of The Art of Fugue] in Anatoly Milka (ed.) Vtorye Bakhovskie chtenia: ‘Iskusstvo fugi’ (St Petersburg, 1993), pp. 83–4. Fifteen years later Gregory Butler confirmed this hypothesis: Gregory Butler, ‘Scribes, Engravers and Notation Styles: The Final Disposition of Bach’s Art of Fugue,’ in Gregory Butler, George B. Stauffer and Mary Dalton Greer (eds.), About Bach (Urbana and Chicago, 2008), p. 120.

8 The significance of the particular division of the number 7 into 4 + 3 is explained and discussed in Chapter 20.

9 The analogy between The Art of Fugue’s structure and the idea of a ‘meta-fugue’ had been first promulgated by Philipp Spitta, Johann Sebastian Bach, vol. 2 (Leipzig, 1880), pp. 682–3.

10 The assumption that Bach dropped his initial decision to connect the fugue for two claviers (XVI) with the canon XVIII is supported by his writing it on a separate bifolio. It is important to bear in mind that making a decision and later abandoning it represent two separate stages. If Bach had not initially intended to place the fugue for two claviers on pages 39–40, there would be no need for the congested writing on page 38. Equally, had he not made up his mind to abandon that idea, the inscription’s characteristics on page 39 would not be so different from those of page 38.

11 The bifolio was cut into two halves and brought in that form to the Berlin Royal Library later on, in 1841. Until then the fugue for two claviers was an inseparable part of The Art of Fugue, as confirmed by the inscription in the left bottom corner, written, as Klaus Hofmann suggests, by J.S. Bach himself: ‘eigentlichen Originalhandschrift vermerkt (11 B.)’. Hofmann, NBA KB VIII/2, p. 22. If indeed this is the case, the composer himself established the pertinence of the fugue for two claviers (at least of this particular manuscript) to The Art of Fugue.