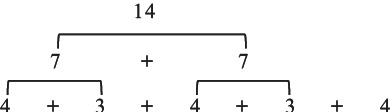

The third and fourth versions of The Art of Fugue, planned after the composition of the Musical Offering (and possibly also after the Canonic Variations on the Christmas Chorale Vom Himmel Hoch, roughly after 1747/1748), show that J.S. Bach changed the conception of his work. Christoph Friedrich, who witnessed and participated in the process, clearly indicated the existence of ‘einen andern Grund Plan.’ This other plan, as Bach’s ensuing actions show, was radically different from the composition’s previous two versions, abandoning the former principle of pair-organisation.1 The new Art of Fugue, as presented in Chapter 10, was based on the following model (Scheme 20.1):

While the framework of the cycle is clear, its significance is not entirely so. This particular model hid a message that was encoded in a numerological symbolic system that is neither verbal nor musical. Within this system and in this particular composition, the number 14 was the organising principle and the single factor that determined the number of fugues regarded as contrapuncti. Expressing the sum of the numerical value of the letters in Bach’s name, it carries a unifying meaning that defines each one of its elements and also its distinctiveness as a whole, joining two groups of seven contrapuncti each.

While the significance of number seven in Christian symbolic systems is multifaceted, given the multiplicity of its meanings in both Old and New Testaments, its particular substructure, where each half of seven fugues is represented by the specific combination of four and three, may provide more determined results.

In seventeenth- and eighteenth-century German studies (for example, in the works of Leibniz) the number seven is always interpreted as a combination of two components: four (as a symbolic representation of the world’s material aspects) and three (in a variety of meanings of the word Geist—spirit), thus read as a symbol of inspiration and of the spirit’s infiltration into substance.2

Such interpretation indeed may reflect the idea of spirituality imbued in The Art of Fugue. However, the division of the 14 units, which comprise the core of the work, into two groups of seven, is not the only peculiarity of the cycle’s numerical construction. Each of these groups is further internally subdivided, in both cases, into four works followed by three. Given Bach’s meticulous attention to numerical details, the fact that the internal units are twice positioned as four and three (rather than three and four) calls for some scrutiny.

Bach’s intellectual environment and personal interests played a significant part in his approach to musical composition. His involvement with the Society of Musical Sciences, founded in 1738 by his student and friend Lorenz Mizler, substantially affected his musical, scientific and pedagogical principles and preferences.3 Despite the fact that Bach was officially initiated into the Society only in 1747, he had socialised with its members and closely followed its discussions and activities since the moment of its establishment.

Bach’s interest in literary and scholarly works increased significantly during these years. He copied musical and theoretical resources and acquired newly published books, as well as older ones, in book auctions.4 Poetry collections of authors with whom Bach collaborated and from which he chose texts for his compositions often demonstrate the poetic technique of paragrams in which Bach was keenly interested. The musical part of his library included, among others, the theoretical works of Angelo Berardi, Johann Joseph Fux, Johann Mattheson, Johann David Heinichen and Johann Gottfried Walther. His collection of theological books shows that he was interested not only in dogmatic, but also in polemical writings, in particular those devoted to non-canonical interpretations of the scriptures, including studies discussing techniques of Kabbalah.5 It is not by coincidence that Bach purchased books that address philosophical and existential issues. As often happens in one’s later years, he became keenly interested in these questions and looked for answers in the books he read. Among these, Caspar Heunisch’s Haupt-Schlüssel über die hohe Offenbahrung S. Johannis [The principal key to the St John’s Revelation], listed in the inventory of Bach’s estate as Heinischii Offenbahrung Joh., calls for particular attention in its explanation of each and every number found in this scripture.6

The presence of this book in Bach’s library was not coincidental. It seems that the St John Revelation occupied a special place in his mind and artistic output. In his cantatas Bach quoted this source more than 160 times, a remarkable number when compared with the 62 quotes from the Gospel according to St Mark, or with the 72 quotes from the book of Ecclesiastes.7

Within the 22 chapters of the Book of Revelations, chapters 4–11 occupy a special place. The most discussed in theological and philosophical treatises, these chapters have been the subject of many works of art, too. In Lutheran sources, they are often presented in a bipartite structure: Das Buch mit den sieben Siegeln (chapters 4–7, ‘The Book with the Seven Seals’) and Die sieben Posaunen (chapters 8–11, ‘The Seven Trumpets’).8

The first group, which includes four chapters, consists of seven episodes, each relating the opening of one of the book’s seven seals. The episodes are again subdivided into two groups of four and three episodes, respectively: the first four episodes describe the four riders of the apocalypse, and the remaining three episodes describe calamities: the martyrs under the Altar, the Lamb’s Wrath, and Silence.

The second group consists of seven episodes, too, respective of the seven angels that blow their trumpets. The subdivision here is similar: four natural disasters (hail and fire, earthquake, water pollution and eclipses) are followed by three woes (torture, plague and war). This division is highlighted by the verse that follows the four disasters with a triple exclamation: ‘And I beheld, and heard an angel flying through the midst of heaven, saying with a loud voice, Woe, woe, woe, to the inhabiters of the earth by reason of the other voices of the trumpet of the three angels, which are yet to sound!’9

Bach could have identified this structure in the Revelation, and then again, as it was presented by Heunisch in his book. It can clearly be seen that this structure is echoed in The Art of Fugue in its new guise (Scheme 20.1). The scheme, however, shows an additional group of four works, the four canons, beyond and above the 14 contrapuncti. This additional group may relate, too, to the central part of the Book of Revelation.

The Glorification of the Divine on His Throne, described at the beginning of chapter four of the Revelation, just before the opening of the seven seals, has been a favourite subject of artists throughout Christian history. Its particular presentations are diverse, but most of them comply with a composition similar to the engraving from the 1488 edition of Johannes Nider’s book Vier und zwanzig guldin Harfen (24 Golden Harps).10 The engraving shows, around the central figure, four small drawings of the ‘four celestial images’.11 The Revelation in Luther’s Bible, owned by Bach, says:

Und die erste Gestalt war gleich einem Löwen, und die zweite Gestalt war gleich einem Stier, und die dritte Gestalt hatte ein Antlitz wie ein Mensch, und die vierte Gestalt war gleich einem fliegenden Adler.

[And the first beast was like a lion, and the second beast like a calf, and the third beast had a face as a man, and the fourth beast was like a flying eagle.]12

In art depictions, these figures are virtually never lined up, but rather spread over the surface. Their description in the scripture agrees with such presentation, portraying the creatures as ‘in der Mitte am Thron und um den Thron’ [in the midst of the throne, and round about the throne].13 Moreover, while in many illustrations of the scene they are distributed over the four corners of a rectangle, the particular position of each image is not fixed (compare Figures 20.1 and 20.2).

Figure 20.1 The Astronomical Clock in Marienkirche, Lübeck. The four corners show the four figures of the Apocalypse. Enlarged details: Top left—the eagle, symbol of St John; top right—the angel, symbol of St Matthew; bottom left—the winged lion, symbol of St Mark; bottom right—the bull, symbol of St Luke.14

In the Revelation story, before the Lamb opens the first seal, the four celestial images partake in the glorification of God:

Und da es das Buch nahm, da fielen die vier Tiere und die vierundzwanzig Ältesten nieder vor dem Lamm und hatten ein jeglicher Harfen und goldene Schalen voll Räuchwerk, das sind die Gebete der Heiligen, / und sangen ein neues Lied und sprachen: Du bist würdig, zu nehmen das Buch und aufzutun seine Siegel; denn du bist erwürget und hast uns Gott erkauft mit deinem Blut aus allerlei Geschlecht und Zunge und Volk und Heiden / und hast uns unserm Gott zu Königen und Priestern gemacht, und wir werden Könige sein auf Erden. … Und die vier Tiere sprachen: Amen! Und die vierundzwanzig Ältesten fielen nieder und beteten an den, der da lebt von Ewigkeit zu Ewigkeit.

[And when he had taken the book, the four beasts and four and twenty elders fell down before the Lamb, having every one of them harps, and golden vials full of odours, which are the prayers of saints. And they sung a new song, saying, Thou art worthy to take the book, and to open the seals thereof: for thou wast slain, and hast redeemed us to God by thy blood out of every kindred, and tongue, and people, and nation; And hast made us unto our God kings and priests: and we shall reign on the earth. … And the four beasts said, Amen. And the four and twenty elders fell down and worshipped him that liveth for ever and ever.]15

Since the fourth century, the four celestial figures became increasingly associated with the four evangelists. For instance, between the sixteenth and eighteenth centuries they often appear on grave slabs, particularly in the main Protestant areas of Flanders, North Germany and Demark;16 The common composition is showing them encircled and distributed over the four corners of the slab.

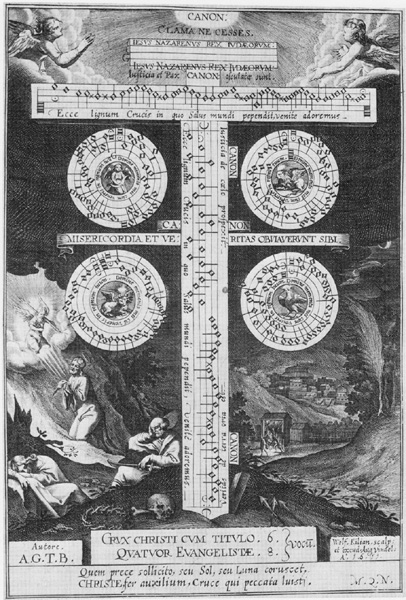

In Germany, these four figures were sometimes expressed emblematically through other media, including through musical emblems. In such compositions, four perpetual two-part canons were composed. Echoing the circular idea of being ‘in the midst of the throne and round about the throne,’ these perpetual canons are traditionally inscribed in cryptic form and on a stave drawn as a circle.17 A typical example is the canon clama ne cesses from the 1618 edition of Adam Gumpelzhaimer’s Compendium musicae (Figure 20.2). In this interpretation, the series of four two-part canons is associated with the four figures of the Revelation. Each one of the four celestial figures is placed within a circle formed by one two-part canon.18 Here, too, they are not arranged in a line but rather in a two-dimensional distribution over the illustration’s area.

Bach’s work during his last period includes several such sets of four two-part canons positioned as a section within a cycle. Beyond The Art of Fugue, they also appear in the Clavierübung III (four duets), in the Musical Offering and in the Canonic Variations (four thematic canons in both cycles).19 The appearance of such canon sets within these cycles often puzzled scholars, performers and publishers, who were unsure how to position them: in the beginning of the cycle, in its middle or in its conclusion? What should be the internal order of these canons? Editors tended to locate them at the end of the work. However, the canons, usually, did not possess the sound and character needed for an effective closure of a cycle. While both performers and publishers may find this fact somewhat frustrating, the nonlinear character of this four-canons set renders the question of their order meaningless.

It would suffice to look at the engraving of Gumpelzhaimer’s canon (Figure 20.2) to realise the complexity of this question, which is applicable to such sets of four canons in The Art of Fugue, the Clavierübung III, the thematic canons in the Musical Offering and the Canonic Variations: their positioning at the end of these cycles is a matter of convention. Four musical canons cannot be located ‘at the corners’ of a cycle or ‘around’ it, as it can be done in pictorial presentations or literary descriptions. Indeed, as is shown in the analysis of P 200 and the Original Edition, Bach defined the position of the canons in the same way as in the other comparable works: ‘at the end by convention.’

Figure 20.2 The canon Clama ne Cesses from the Compendium musicae by Adam Gumpelzhaimer (Augsburg, 1611).

The comparison reveals the parallelism of numerical structures of chapters 4–11 in St John’s Revelation and the final version of The Art of Fugue. However, it would be a distortion (or even vulgarisation) to regard The Art of Fugue as a musical equivalent of the Revelation, or perceive the four two-part canons as a musical depiction of its four creatures (or, for that matter, of the four Gospels). The significance of the detected structural correspondence is more akin to numerological word relations that indicate a hermeneutic comment rather than a lexical identity obviously impossible. In this sense, these two great works can be observed as not only two parts of a paragram, the related parts of which go beyond numerical equivalence (which in this case is 14), but two numbers that share the same structure (seven and seven, each made out of four and three) and therefore, by allusion, echo similar meanings.

In the same way, the life circumstances of two great human beings may comment on each other in their life paragram. At the end of his life journey, St John was granted a revelation about the future of the world. It could just be that Johann Sebastian Bach, in his later years, was granted a revelation of the subject to which he devoted himself, The Art of Fugue. Whether by divine coincidence, a Jungian synchronicity of a ‘common psyche’ or a simple human design, the affinity between these two works is a subject about which one might feel compelled to keep thinking. And rethinking.

1 However, Bach’s principle of gradual increase (Steigerungsprinzip) in the complexity of contrapuntal techniques remained intact, as did the general organising factor that determined the number of 14 fugues.

2 See, for example: Caspar Heunisch, Haupt-Schlüssel über die hohe Offenbahrung S. Johannis (Schleusingen, 1684), pp. 26–31; Johann Jacob Schmidt, Biblischer Mathematicus, oder Erläuterung der Heil: Schrift aus den Mathematischen Wissenschaften: Der Arithmetic, Geometrie, Static, Architectur, Astronomie, Horographie und Optic (Zullichau, 1736), pp. 14–18; Ludwig Prautzsch, Vor deinen Thron tret ich hiermit: Figuren und Symbole in den letzten Werken Johann Sebastian Bachs (Stuttgart, 1980), p. 12; Erich Bergel, Bachs letzte Fuge: Die ‘Kunst der Fuge’, ein zyklisches Werk: Entstehungsgeschichte, Erstausgabe, Ordnungsprinzipien (Bonn, 1985), pp. 147–8.

3 In a letter to Johann Nikolaus Forkel from January 13, 1775, Philipp Emanuel writes that his father taught his pupils to omit ‘all the dry species of counterpoint that are given in Fux and others’ (NBR, no. 395, p. 399; ‘In der Composition gieng er gleich an das Nützliche mit seinen Scholaren, mit Hinweglaßung aller der trockenen Arten von Contrapuncten, wie sie in Fuxen u. andern stehen.’ BD III/803, p. 289). This description quite matches Bach’s principles as they were prior to the mid-1730s, when Emanuel left his paternal home, never to return. Therefore he was probably unaware of the changes in Bach’s views during the late 1730s and thereafter, when Bach recommended Mizler to translate Johann Joseph Fux’s treatise from Latin into German in order to make it more accessible to music students. Further, Bach probably copied Angelo Berardi’s Documenti armonici (1687), which by that time became a bibliographic rarity. He also explored the technique of strict style counterpoint by copying stile antico works, especially by Giovanni Palestrina.

4 A receipt from mid-September 1742 confirms Bach’s purchase of theological literature for the amount of 10 thalers in a Leipzig auction (BD I/123, p. 199).

5 In this regard, it is appropriate to specify, for example, Johann Müller’s book that was in Bach’s library, Judaismus oder Jüdenthum, das ist: Außführlicher Bericht von des Jüdischen Volckes Unglauben, Blindheit und Verstockung: Darinne Sie wider die Prophetischen Weissagungen von der Zukunfft, Person und Ampt Messiae, insonderheit wider des Herrn Jesu von Nazareth wahre Gottheit … mit grossem Ernst und Eifer straiten (Hamburg, 1644).

6 The importance of numerological exegesis is apparent in the full title of the book: Haupt-Schlüssel über die hohe Offenbahrung S. Johannis welcher durch Erklärung aller und jeder Zahlen, die darinnen vorkommen und eine gewisse Zeit bedeuten zu dem eigentlichen und richtigen Verstand Oeffnung thut (Schleusingen, 1684). A new edition of this book, by Thomas Wilhelmi, with contributions by Christoph Trautman and Walter Blankenburg, was published as part of the international workshop of theological Bach research in Schlüchtern, Hessen (Basel, 1981).

7 Ulrich Meyer, Biblical quotation and allusion in the cantata libretti of Johann Sebastian Bach (Lanham, Maryland, 1997), pp. 215–16.

8 Die Offenbarung des Johannes. Die Bibel. Nach der Übersetzung Martin Luthers. Das Neue Testament (Stuttgart, 1985), p. 289.

9 Revelation 8:13, King James Bible Authorised Version, Cambridge University Edition (1985).

10 The image can be seen on the website of Munich’s Digital Library Centre (Münchener digitalisierungs Zentrum, Digitale Bibliothek (http://daten.digitale-sammlungen.de/~db/0005/bsb00054285/images/index.html?id=00054285&groesser=&fip=193.174.98.30&no=&seite=5). There are many similar depictions of this scene of which the following are just a few examples: Ninth century: the frontpiece of the book of Revelations in the Bible of San Paolo Fuori le Mura, in Rome; thirteenth century: the stone carving over the west portal of the Angers Cathedral, in France; fifteenth century: Albrecht Dürer’s 1497–98 woodcut of The Revelation of St John, 13: The Adoration of the Lamb and the Hymn of the Chosen (at the Staatliche Kunsthalle, Karlsruhe), and many more.

11 In Luther’s translation, ‘vier himmlische Gestalten’ (Revelation 4:6).

12 Luther’s Bible (Revelation 4:7); English: King James Bible.

13 Ibid. 4:6. English: King James Bible.

14 Photograph taken by A.P. Milka (2006). The clock is a 1961 reconstruction of the sixteenth-century clock that was destroyed in 1942.

15 Revelation 5:8–10 and 5:14. English: King James Bible.

16 These areas have a considerably common cultural background, being heavily involved in the Eighty Years’ and Thirty Years’ Wars as well as united by the economic interest in the trade of linen and wool for all Europe.

17 Editor’s note: presenting each of these four figures in a circle does echo the Revelation description, but is also, probably, related to the Merkavah vision in the book of Ezekiel, to which the Revelation alludes poetically. The element of a circle is far more evident there: ‘Now as I beheld the living creatures, behold one wheel upon the earth by the living creatures, with his four faces. The appearance of the wheels and their work was like unto the colour of a beryl: and they four had one likeness: and their appearance and their work was as it were a wheel in the middle of a wheel’. (Ezekiel 1:15–16); English translation: ibid. The music emblem borrowed this principle to create two identical circular parts moving within the one-staff wheel of the canon.

18 The inscription at the bottom of the engraving states: eight voices for the four evangelists (Quatuor Evangeliste 8 vocii).

19 In the Canonic Variations all four thematic canons appear in one variation; the printed version of the composition has this variation as the closing one, while in the manuscript copy it occupies a centre position.