Indications of a Third Version in P 2001

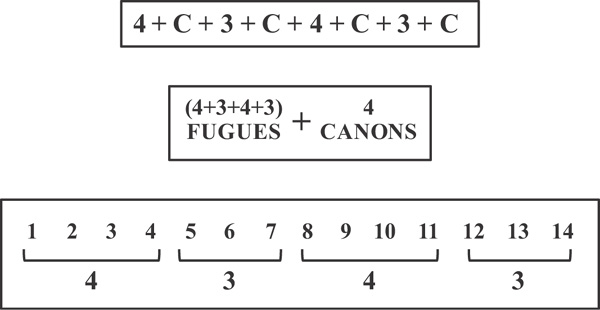

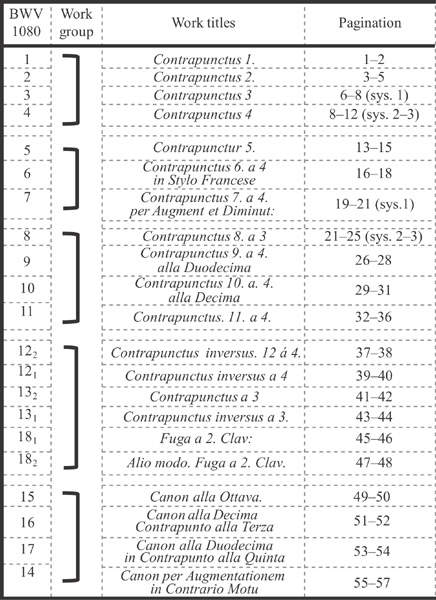

The new version offered a completely new outlook on the cycle, requiring the realisation of a fugue sequence structured as (4 + 3) + (4 + 3) and supplemented by four additional canons.2 This structure differs significantly from the one shown on Schemes 9.3 and 9.4. Most importantly, it breaks, at least in part, the pairing principle developed in the First and Second Versions. Thus, while the numerical expression of Bach’s name, the number 14, does play a decisive role in the cycle’s structure, the Third Version includes a total of 14 individual fugues without counting in the four canons. Allegedly, an alternative positioning of the canons could be considered, in a way more similar to the former model, distributing them among the fugue groups (Scheme 10.1, top). This structure would agree with Spitta’s idea of a meta-fugue.3 However, it did not happen. The final version of the composition, presented in the first printed edition, suggests that Bach decided to group the four canons at the end of the cycle (Scheme 10.1, middle). A group of 14 fugues, then, constitutes the main body of the cycle.4

The fugues of the cycle are organised in two structurally identical halves, a pair of 7 + 7 fugues. To make this new division more persuasive, the resemblance between the new pair of components needed to be highlighted, so that the correspondence is expressed not just in their sheer numerical subdivision into 4 + 3 but in other properties, too. Bach’s next steps served this purpose.

Based on the composer’s vein of thought and the two former versions of The Art of Fugue, present in the Autograph, each group of four and of three fugues will be examined separately.

Fugues 1–4

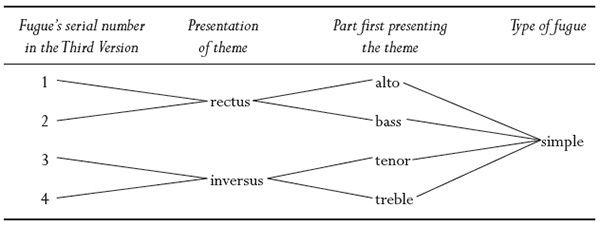

Promoting in part Spitta’s perception of the cycle’s structure as a meta-fugue, the first four fugues could be looked upon as a meta-exposition, in which each one of the fugues is regarded as an entry stating the theme. Obviously, each should present the theme in its basic form (the first four notes as half notes).

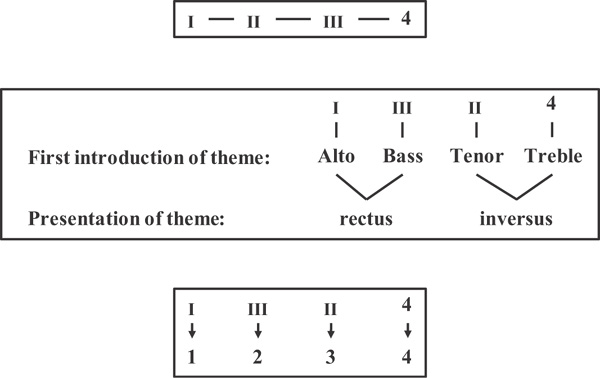

However, only the three first fugues of the Autograph comply with this description: they are simple and present the main subject of the collection in its original form, while all the subsequent fugues present thematic variants that include passing notes and other figurations. Further, in each of these first three fugues the theme is first stated by another part: the alto presents the theme in fugue I; the tenor opens fugue II with the inverted theme; the bass opens fugue III, again with the main theme. An expected fourth fugue would thus open with the treble, stating the inverted theme. It should also be a simple fugue, presenting the theme with no ornamentation or additional figurations.

There is no such fugue in the Autograph. It does appear, however, as Contrapunctus 4 in the Original Edition of The Art of Fugue.5 Bach composed it especially for the Third Version, moreover, with precisely all the expected parameters. It is a simple fugue; its theme, introduced in the treble voice, is presented in inversion but without any ornamentation (Example 10.1).

The new structure, presented in the Third Version, shows both its affinity to the first two versions (which are realised in the Autograph) and the features in which it differs from them.6 The top of the scheme shows the first pair of the two simple fugues, composed on the original and the inverted themes. The third and fourth fugues present a similar structural unit. Bach’s subsequent actions would aim to move away from a ‘two pairs’ structure, integrating instead the four fugues so that they form a cohesive group.

The musical theme of the collection creates a basic, general similarity among all its fugues. To mark a group of fugues within this collection as an interconnected unit, Bach resorted to parameters of contrast. The most obvious contrasts among the first four fugues are the theme inversions. To highlight these, the composer exchanged the position of fugues II and III, weakening the link of the initial pair I–II and creating instead a strongly interrelated set of four, shown at the centre of Scheme 10.2.7 The cohesion of this new set is now based, on one hand, on the contrast between the two fugues that present the theme in its original form and the two that present its inversion, and on the other hand on the simulacrum to an exposition of a meta-fugue, where each fugue introduces the theme in a different part: alto, bass, tenor and treble. This first quartette, created by the addition of a new fugue and the repositioning of pre-existing ones, can be seen at the bottom of Scheme 10.2.

Bach addressed a specific trait in the resulting set of four fugues. Fugue III (number 2 in the Third Version) is the only one in the first two versions that ends on a half-cadence, a very unusual ending for any independent piece. Bach’s decision to use such a cadence in the first two versions was intended to connect fugue III to fugue IV, since these two fugues did not gravitate toward each other as the other pairs did (see Example 7.2).8 The half-cadence at the end of fugue III would compensate for this shortcoming, creating an expectation for continuity, thus leading toward fugue IV. In the Third Version, however, there was no more need for this half-cadence, since the pair III–IV disappeared. The new fugue, number 4, replaced fugue IV, and fugues II and III interchanged positions. Consequently, fugue III (now numbered 2) rather than calling for continuation, closed a pair, and the half-cadence was replaced by an authentic one.

The scheme of the first set of fugues in the Third Version, thus, presents four simple fugues, in which the pair 1–2, where the theme is presented in its original form, contrasts the pair 3–4, where the theme is inverted. Each of the four fugues starts on a different voice (Table 10.1).

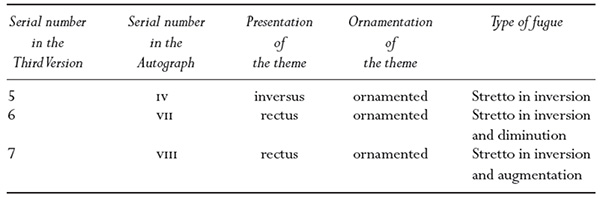

Fugues 5–7

The second group in the Third Version of The Art of Fugue is a set of three fugues. To form it, Bach combined the stretto fugue IV, which in the first two versions belonged to the second pair, with the pair of stretto fugues VII and VIII, creating a group of the three stretto fugues on positions 5, 6 and 7 respectively, ordered in increasing complexity. Fugue IV is a stretto fugue in inversion with no diminution or augmentation. Next comes fugue VII, which is inverted with diminution, and last is fugue VIII, based on double augmentation9 (Table 10.2).

Table 10.2 shows one more detail: fugues VII and VIII are based on the original theme, giving the impression that in this particular pair Bach transgressed the principle, otherwise strictly observed by him, that requires a pair of fugues to be joined by contrasting forms of the theme. Example 10.2, which presents the initial bars of both fugues, shows, however, that this principle is, in fact, closely followed.

While the first appearance of the theme is indeed related to its original presentation (that is, opening with an ascending fifth), the immediate answer, in both cases, is its inversion. Further, the theme in the lower part of fugue VIII is, in fact, the inversion of its dotted, inverted form in the top part of fugue VII. Indeed, the most visible contrast here is the diminution—the theme’s rhythmic appearance and its position within the texture of the fugues.10 A comparison between the positions in which the theme in diminution appears in the initial strettos of both fugues and the positions of the augmented theme shows an opposite result (Tables 10.3 and 10.4). Thus, the principle of opposition is realised in the stretto fugues not only in their theme presentations and in their types but in their initial stretto constructions, too.

Fugues 8–11

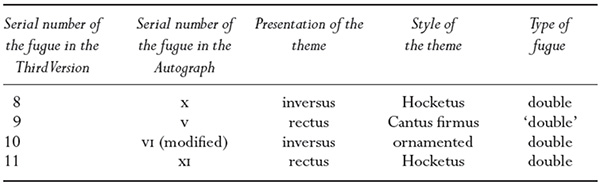

The second set of four fugues in the Third Version was meant to consist of double fugues. The most suitable double fugues in the Autograph are X and XI. Fugue V, on a cantus firmus, which has two themes, would fit here, too.11 The set of four fugues is thus short of one double fugue. No other fugues of this type were available in the Autograph. One possible solution would be to compose a new fugue, as Bach did for the first set of four. Instead, he remodelled fugue VI—a simple fugue with a consistent countersubject—into a double one. Upgrading the status of the consistent countersubject into a main subject, he composed a new exposition and inserted it at the very beginning of the fugue. In this way the consistent countersubject becomes its first subject, its exposition preceding the original beginning of fugue VI. There are no further changes in this fugue. The second set of four fugues is presented in Table 10.5.

The process of formation of the second set of four fugues was similar to that of the first one: Bach revised and remodelled one of the fugues and changed the order of the other three. Following the logic that lies at the foundation of this cycle, the permutation of these fugues served two purposes: to deconstruct the solid fugue pair X–XI and to ensure the alternation of original and inverted theme presentations. As in the first set, these steps were taken in order to weaken the perception of these fugues as a pair and to highlight instead the cohesion of the four as an integrated group.

Fugues 12–14

The last triad of fugues was present in the Autogaph and did not require any additional actions for its organisation. These are the three mirror fugues. The first two were fugues XIII and XIV in P 200. The fugue for two claviers to which the serial number xvi was assigned, when discussing the Second Version, was put into this group but deserves a special discussion.12

In Bach studies, starting from Philipp Spitta’s description, fugue xvi always appears as a ‘setting’ or an ‘arrangement’13 of fugue XIV and is therefore usually removed from The Art of Fugue. There are many reasons to support such an opinion. The chief one was the fact that the material of fugue xiv (Contrapunctus a 3 rectus and inversus, pp. 41–4 in the Original Edition) was fully used for fugue xvi. The first to draw attention to this fact were Robert Schumann and the librarians of the Berlin Royal Library.14 Since then, the perception of the fugue for two claviers as an arrangement, disconnected from The Art of Fugue, reappeares regularly to this day, and there is hardly any study expressing doubt on this account.

Such an attitude would be justified if The Art of Fugue, as a cycle, were intended for performance on the concert stage. In such a case, the repetition of musical material, even as a different type of fugue, might create certain monotony and be ineffective. However, just like The Well-Tempered Clavier, the Clavierübungen, Inventions and Sinfonias and some other collections and cycles, The Art of Fugue was not composed for concert performance. All Bach’s contemporaries, and especially Philipp Emanuel, described it as a kind of manual for composition, a practical guide for writing fugues.

The fugue for two claviers (xvi) demonstrates a new composition technique and an additional type of fugue, which had not yet been featured in the cycle: a fugue with an accompaniment. Fitting it into the cycle, Bach proved that practically any imitational form—a fugue or a canon—could be composed with or without an accompaniment. There are other such examples in Bach’s own output, several in the Musical Offering (the Fuga canonica, two fugues in the sonata, and the Canon perpetuus) or the fugue Allein Gott in der Höh sei Ehr (BWV 676) from the Clavierübung III.

An accompaniment could be of various types: one melodic line, as in the Fuga canonica or in BWV 676; several voices; a chordal harmonic support or a figured bass that a cembalo player would extemporise (for example, in the fugues of the Musical Offering). In doing this, Bach demonstrates a certain kind of counterpoint originating in cantus firmus technique: composition of new counterpoint to an already existing melody (or melodies), applied here into the major-minor system. The fugue is first presented as a contrapuntal structure in its purest form, without any accompaning voices; then the text moves to a derivative combination: the same fugue with new contrapuntal voices, some of which act as accompaniment. This is the reason for which the second clavier was introduced.15

The opinion that this fugue belongs to The Art of Fugue is indirectly supported by the fact that, being technically more complex than the preceding one, it complies with the ‘ascending complexity’ principle, which is one of the cycle’s main characteristics.

Earlier we considered Bach’s intention to fit this fugue in a given space, next to canon XV (see Scheme 9.3). Later, so it seems—probably as a result of a new idea—he wrote the fugue on a separate bifolio. It is unlikely that Bach would write into the Autograph of The Art of Fugue an arrangement that he did not intend to include in the cycle. On top of that, the paper type, on which the fugue was written, is the same one used for the previous mirror fugues (XIII and XIV). The size and dynamics of the handwritten notes, the ink and the rastration are absolutely identical to the two previous fugues. All this indicates that they were written during the same period of time and with the same purpose.16

This can be confirmed by other factors, too. Initially, the fugue was written on a separate bifolio. Eventually, the double sheet was cut in two and in this form deposited in the Berlin Royal Library. Until then, the fugue for two claviers was an integral part of the Autograph as evidenced by the manuscript’s features. The inscription ‘eigentlichen Originalhandschrift vermerkt (11 B.)’ on the right bottom corner of the title page (see Figure 4.7), made by J.S. Bach, as Klaus Hofmann thinks, also supports this notion.17 This inscription indicates that the whole set of music sheets that formed part of the Autograph’s main corpus consisted of 11 bifolios. Consequently, the double sheet with the fugue for two claviers (xvi), which coincides precisely with all the material characteristics of the 11th bifolio, should be considered part of the collection. Moreover, if Hofmann’s notion is correct, and the discussed inscription was indeed the composer’s own, then the pertinence of the fugue for two claviers to this cycle was designated by J.S. Bach himself, and its exclusion from the whole happened only as late as 1841, in the Royal Berlin Library.18

Permutations, permutations, permutations…

The exclusion of this bifolio from the manuscript, though seemingly solving the repetition of materials in fugues XIV and xvi, created new questions. For example, the function of this mirror fugue, separate from The Art of Fugue, becomes unclear and quite problematic: why would Bach use the modified theme from this cycle for an instrumental ensemble (two claviers without accompaniment), which he had never used for any independent pieces? Besides, it is hard to believe that while working on such a grandiose project as The Art of Fugue, Bach would engage in arranging and clean copying a fugue that he did not intend to include in the cycle. It does make sense that this fugue is not leftover ‘refuse’ but an actual, integral part of the great work.

A short discussion of mirror fugues may be in order here. Deciding whether the first presentation of a theme in a mirror fugue is in prime or inverted position is impossible, unless some artificial labelling is imposed, simply to facilitate discussion of these pieces and a better understanding of their organisation in the cycle.

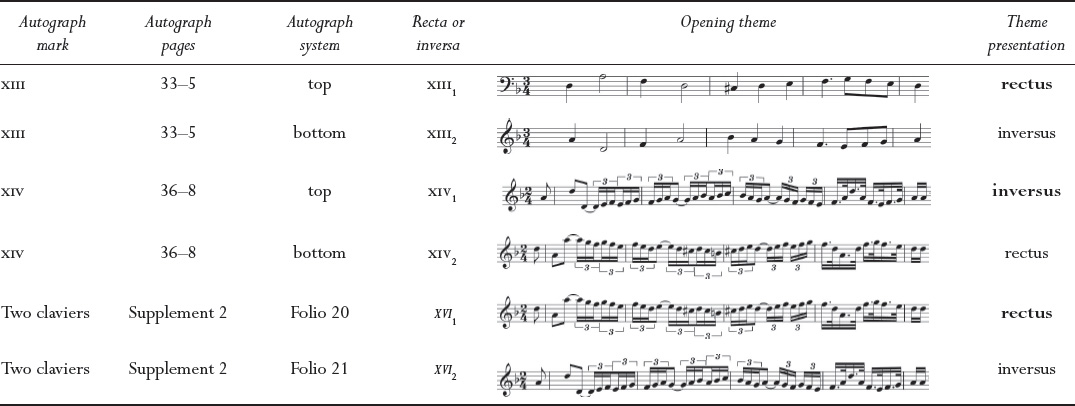

Two mirror fugues appear in the Autograph, numbered there as XIII and XIV; the third is the mirror fugue for two claviers, written on P 200/1–2. The two mirror fugues in the Autograph’s main body, numbered XIII and XIV, are written in double systems, one above the other, each member visually mirroring its companion fugue. Since each one of these fugues is, actually, two fugues, they will be individually labelled XIII1, XIII2, XIV1 and XIV2. The fugues written on the top systems are thus marked XIII1 and XIV1, and are regarded as the two recta fugues. The two fugues on the bottom systems are marked, accordingly, XIII2 and XIV2 and regarded as the inversae fugues. The importance of this differentiation will become apparent in the Original Edition, where rather than one above the other, as in the Autograph, the fugues are printed one after the other. Here, the presentation of the theme in the fugue positioned first in a pair will define the subject as rectus or inversus for the pair.

The third mirror fugue, written for two claviers and marked in this discussion as xvi, poses a difficulty. Here the two mirror fugues were not written one above the other, but on a bifolio, which was torn in the middle into two folios (P 200/1–2), one fugue on each folio. Here there is not even an implied hierarchy of a ‘top system’ versus a ‘bottom system’. However, the two folios were marked as ‘20’ and ‘21’, which will be respectively substituted, when this fugue is under discussion, with the markings ‘xvi1’ and ‘xvi2’, regarding xvi1 as the recta of this pair.

Thus, the mirror fugues, as presented in the Autograph and their internal hierarchy defined, can be described as in Table 10.6.

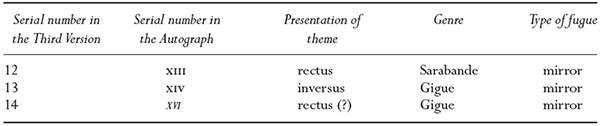

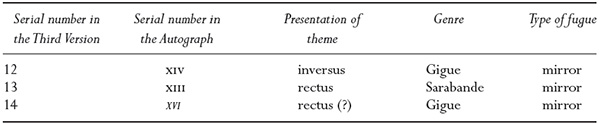

This set of three mirror fugues, after having been adopted into the Third Version in chronological order, introduces yet another unifying element: all three fugues allude to dance topics, a first such reference in the cycle (Table 10.7).

It is unlikely, however, that Bach would leave the group as in Table 10.7. The fugues in positions 13 and 14 share the same theme and, in fact, are constructed identically. The main difference is that the second among them has an additional accompaniment (the contrapuntal part). Thus, the fugue in position 13 presents an initial composition, and the one in position 14 its derivative. In this aspect, these two fugues are correctly positioned, since they demonstrate a gradual increase of contrapuntal complexity, which is a main didactic principle in The Art of Fugue. Nevertheless, Bach could not ignore the motivic repetition in adjacent parts of the cycle. However, there was no way to get around this problem, since the repeated musical material is here ingrained in the composition itself.

While Bach could renounce this fugue and thus avoid repetition, such a step would prevent him from presenting a more complex type of counterpoint, which was one of his two most important principles of composition. Another option would be to somehow diminish the perception of repetition by reordering the fugues’ dance topics, creating a slightly more diversified scheme (see Table 10.8).

The canons in the Third Version

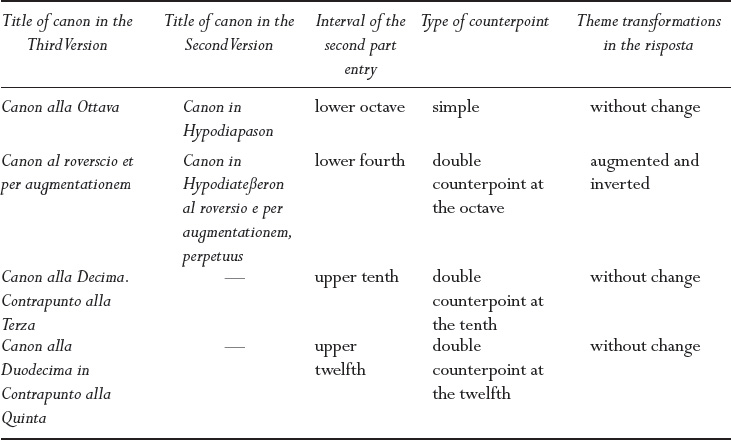

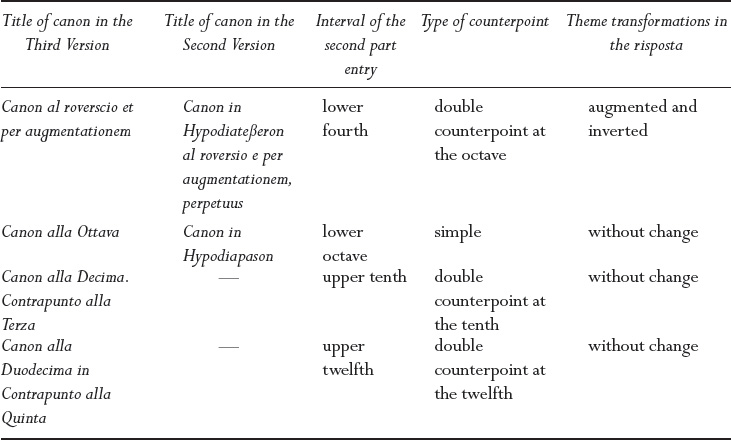

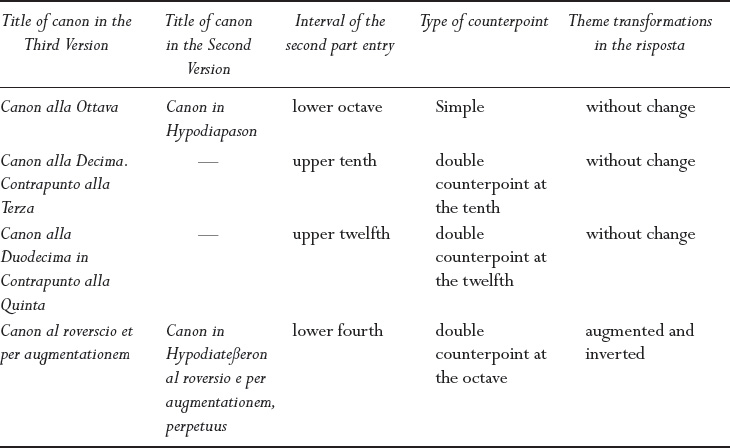

The Art of Fugue should be concluded, according to its Third Version, with a group of four canons. Two of them—the Canon in Octave (Canon in Hypodiapason) and the Canon in Augmentation (Canon in Hypodiateßeron. al roversio e per augmentationem, Perpetuus), already exist: they occupy positions IX and XV in the Autograph. Bach composes two additional canons, built on the intervals of 10th and 12th, respectively. The order of their presentation requires inspection.

There are several organising criteria according to which a series of canons could be ordered. One criterion would be their sequencing by the interval in which the voices are introduced, starting from the smallest interval. Another criterion would adhere to degrees of sophistication, starting from simple counterpoint and proceeding to more complex forms. The four canons that Bach wanted to introduce into The Art of Fugue show that these two criteria were inconsistently applied.

Presenting the canons in the order in which they might have been composed is tentative at best. There is no doubt regarding the chronology, reflected in the Autograph, of the first two canons. However, the Autograph of the remaining two canons is lost, and therefore they are recorded here in the order they appear in the Original Edition. In fact, this order seems to follow the ascending complexity principle, having the simple counterpoint canon being followed by three canons in double counterpoint. These last three are sequenced according to an ascending interval size: octave, 10th and 12th (Table 10.9).

This order is consistent with tradition and coincides with the ways in which most common types of counterpoint are described in treatises known to Bach.19

The logic in this order is highlighted by the title of the Canon in Augmentation, explicitly stating that it is written in counterpoint of an octave. Bach’s special indication of this fact is confirmed by Johann Christoph Friedrich Bach’s note at the top of the first page of P 200/1–1, where the canon was inscribed: ‘Der seel. Papa hat auf die Platte diesen Titul stechen laßen Canon / per Augment: in Contrapuncto all octava, er hat es aber wieder / ausgestrichen auf der Probe Platte und gesetzet wie forn stehet’.20 The ‘as follows’ states: Canon p[er] Augmentationem contrario motu [Canon in Augmentation and Inversion]. Bach’s original title, therefore, did specify the counterpoint at an octave in the canon’s title. This may explain why one variant of the canons’ organisation was the one presented in Table 10.9.

Still, there was one more detail that Bach might have found unsatisfactory: following intervallic order, the Canon in Augmentation and Inversion is positioned here second, while usually the composer would have preferred to position such a complex canon at the very end.21

The difference in the author’s view of these two canons becomes clear when noticing that, while the first canon in Table 10.9 is titled after its entry interval (the octave), the title of the second describes its type of counterpoint (in augmentation and inversion).

The titles of the two remaining canons in this group indicate both the entry interval and the type of counterpoint: Canon alla Decima Contrapunto alla Terza, and Canon alla Duodecima in Contrapunto alla Quinta. Moreover, the name of the entry interval coincides with the type of counterpoint. This double criteria (by type and by interval) of classification allowed ordering manipulations. Johann Christoph Friedrich’s inscription reflects Bach’s indecisiveness concerning the classification principle and the canons’ sequence. A hypothetical order that follows exclusively the ascending entry interval principle (fourth–octave–tenth–twelfth) is shown in Table 10.10.

However, this organisation does not allow for the ascending complexity principle to be followed, given that the most complicated canon is now located at the beginning of the group sequence (instead of at its end), while the simple canon is occupying the second place (instead of being at the beginning, as in Table 10.10). Table 10.11 shows that Bach then moved the Canon in Augmentation and Inversion to the last position, to better comply with his ascending complexity criterion.

In fact, this step may have accommodated the entry interval principle, too, given that the entry interval of a fourth is now below the main line, rather than above it. Most Bach studies agree that this is, most likely, the final order intended by the composer.22

Nevertheless, the order in which these canons actually appear in the Original Edition follows, unexpectedly, the one presented in Table 10.10.23

The inscription that Johann Christoph Friedrich Bach wrote on P 200/1–1 leads to several key inferences:

• It ascertains that the Third Version of The Art of Fugue was the one that had been sent by Johann Sebastian to the engraver.

• It confirms that Bach received the proofs and was able to insert his corrections in them.

• If the engraving followed the order of the print, from the beginning of the cycle to its end,24 the inscription could serve as proof that with the revision of the Canon in Augmentation and Inversion, as written on P 200/1–1, J.S. Bach had finished the engraving proofreading of the whole Art of Fugue in its Third Version.

• In such a case there would be grounds to suggest that this version was not only wholly prepared—with a full set of clean engraver copies—but even existed as proof copies, which Bach revised.

The Third Version in print?

The Third Version was not published, although Bach did prepare it for publication and visualised its printed edition.

How was the Third Version supposed to look in print? As the analysis of the Autograph shows, Bach did not finalise it, although he did make several attempts to that end, as betrayed by the Canon in Augmentation on pages 38–9 of the Autograph.25

All the facts point to this canon’s second part (on p. 39) concluding the composer’s work on the five binios folder that constituted the main body of P 200 and left it at that. As it stands, the Autograph holds the First and Second Versions, and it also served as a draft for the Third Version.26

The accomplishment of the Third Version required the reworking of several pieces,27 permutation of others28 and composition of new ones.29 Bach could not use P 200 for the new composition, into which the Third Version eventually turned. It is only natural that the folder’s structure of the Third Version would turn out to be completely different from the first two.

It seems reasonable to regard the fugue for two claviers (P 200/1–2) as the only evidence left of a once existent Third Version’s folder. The fact that this fugue is written on a separate bifolio (despite the apparent initial intention to start it on the middle of page 39 in the Autograph), shows that at that point, with the new idea of the cycle, Bach dropped the principle of continuous inscription, where each piece may begin at any position on a page. From the Third Version onwards he maintains another principle, according to which every piece is written separately, starting at the top of the page. Such an approach to the performance of permutations—and there were quite a few of them—became easily operable.

Indeed, starting from Contrapunctus 12, as the first mirror fugue is called in the Original Edition, every piece (the three mirror fugues and the four canons) is written on two pages, or more precisely—and eventually—on one page spread.30

The sequence of pieces in the Third Version and their provisional order on the printed pages is presented in Scheme 10.3.

It is interesting to note that the two mirror fugues in the positions 12 and 13 (XIII and XIV in the Autograph) are not organised in consecutive order. The order in the Original Edition is inverted: 122, 121, 132 and 131. It is unclear why would Bach choose to do it this way, but it is possible that he decided to start with an inverted theme as a contrast to Contrapunctus 11, which was based on the theme’s rectus presentation, or to create contrast with the new fugue that will replace xvi in the Fourth Version. However, it is clear that this reordering required a considerable process of repagination.31 The pagination, as it appears in Scheme 10.3, can only be assumed, since in reality it could have been just a collection of pieces in engraver copies (Abklatschvorlagen) and in proofs (Probe Platten); it is reasonable to assume that they were printed. After all, both the engraver copies and the proofs did exist in reality. The printouts, made from the engraver copies of the Third Version, are present in the Original Edition of 1751 and 1752. As for the proofs, the Nota Bene by J.C.F. Bach on the first page of the Canon in Augmentation does imply that J.S. Bach revised them.

The proofs

The first to call attention to the proofs created in the process of Bach’s publications was probably John Alexander Fuller-Maitland, in his study of the Clavierübung II, which is kept at the British Library in London. Fuller-Maitland identified one of them (shelfmark K.8.g.7) as a set of proofs: ‘a close comparison of this with the second state of the publication makes it clear that this copy of the first state was used by the composer as a set of proof sheets.’32 Fuller-Maitland, however, did not ask whether the set he was studying was a preliminarily printout, before the main run, or if Bach simply used one of the final copies from the run.

Decades later, in 1990, Gregory Butler discussed a similar problem while studying materials from the original edition of Clavierübung III.33 He drew attention to two printed copies of this work, which are referred to as A7 and A15 in Manfred Tessmer’s study.34 Tessmer, however, did not identify these documents as proofs. The first to do that was Butler, after a meticulous analysis of both sources and their comparison with other preserved copies. The edition proofs of the part of A7 that was printed in Leipzig (marked by Butler as ‘L’) were poorly printed on a paper of low quality and of three different types, and this in contrast to the main run, the print quality of which was much higher, the paper of good quality and of one type. Butler describes this set:

Physically, L in A7 presents a striking contrast to its counterpart in all of the other nineteen exemplars of the print. The pages are covered with creases, blots, and streaks of printer’s ink, and overall present a very messy appearance. Also, in some cases, there are multiple impressions, which create a blurred effect.35

Butler also draws conclusions from these documents: ‘Its unsightly appearance and the poor quality of the paper would further suggest that L in A7 was a proof copy of the section printed in Leipzig’.36

However, the proof pages in A7, printed in Nuremberg, were of the same kind of paper as the main run. Nevertheless, they belong to A7, which, in Butler’s view, ‘remained in Bach’s possession until his death’.37 If this is the case, it means that any sort of paper could be used for proofs prior to printing the main run.

Another source considered by Butler to be a set of proofs is encoded as A15. It carries no corrections and is printed on a high quality paper: 19 sheets on the same paper that was used for the main run of the Musical Offering (BWV 1079), eight sheets on the paper of the Leipzig portion of the Clavierübung III’s main run and the remaining 13 on the paper of the Nuremberg portion of the same run.

The situation with The Art of Fugue seems more complicated, because the only documented evidence for the existence of proofs for this work is Johann Christoph Friedrich’s Nota Bene on the first page of the engraver copy of the Canon in Augmentation (P 200/1–1). Strictly saying, it is only this particular canon that is mentioned in the Nota Bene. This might be the reason nobody ever discussed proof sheets (in plural) in regard to The Art of Fugue. In this case, it is assumed by default that one can safely talk only about a single proof sheet.

There is more indirect evidence, besides J.C.F. Bach’s note, of the existence of proofs. It does not coincide with the notion of one single proof sheet. The distance between Leipzig, where Bach lived, and Zella, where the engraver resided, is more than 200 km, with part of the way, after Arnstadt, through the difficult path of Thuringia’s forested mountains. The communication in Bach’s times—either by post or by personal travel—was possible but still far from easy. In such conditions, organising the delivery of the single Canon in Augmentation’s proof copy or, even worse, sending the proofs one by one, would hardly be cost effective.

It is unlikely that the Canon in Augmentation was the sole piece to be printed for proof reading. What would be the special need for a proof copy of this piece, specifically, to be checked by Bach? Taking into account the manuscript, the engraver copy, the genre of the piece, the construction of the whole cycle, the particularities of the Original Edition and any accompanying documentation, there is nothing that casts any light on such a special need.

According to the preserved inventory of Bach’s property after his death, the engraver Johann Heinrich Schübler received an honorarium of 2 Reichsthalers and 16 Groschen for the engraving of The Art of Fugue.38 This is 25 percent more expensive than the cost of a golden ring (as marked in the same inventory) and almost equal to the cost of the spinet.39 It is highly questionable that the price for engraving one canon, or even half of The Art of Fugue, could be the same. More likely, a much larger body of texts stands behind this commission to the engraver: the whole Third Version. If the composition were to be engraved as a whole, however, it is doubtful that the proofs would be printed just of one canon and not of the whole cycle, as was the usual practice.

The fact that a set of proofs was made during the publication process of the Clavierübung III is essential.40 It supports the view that a similar set was prepared for The Art of Fugue and that Bach revised it before sending the engraved material to print.

Christoph Wolff suggests that the gray-blue folder P 200/1 contained, at a certain point in time (seemingly earlier than their deposit at the Royal Berlin Library) the missing part of the whole set of engraver copies: ‘… the wrapper inscribed by Johann Christoph Friedrich Bach, which possibly contained the engraver’s copy’.41 Indeed, a careful examination of the blue cover reveals traces of vertical folding marks, probably produced by its wrapping a significant amount of papers, larger than just the supplements it contained.

Wolff deems that those were engraver copies.42 However, engraver copies, usually, would not be returned to the composer. Therefore, if Wolff’s hypothesis concerning The Art of Fugue’s printing materials being included in that folder is correct, then these could be the set of proofs rather than the engraver copies.43 This means that the proof sheet (Probe Platte) referred to by J.C.F. Bach could, most probably, be a part of that whole set.

It is quite plausible, thus, that J.S. Bach himself prepared the Third Version for print: it was fully engraved, its proofs revised and corrections introduced. The whole cycle would have been issued in this form, unless one point was judged by Bach as a gaucherie: the repetition of musical material in the fugue for two claviers and, more generally, the very introduction of two claviers into the cycle.

Two points must be considered when discussing the fugue for two claviers. First, it should not be excluded that the appearance of such an instrumental ensemble could be one of Bach’s ideas for reinforcing the concluding role of a last piece in a multi-movement cycle. Second, Bach’s steps might indicate that he thought some trait of the fugue for two claviers unsatisfactory and therefore decided to remove it. In doing so he revised the Third Version and created a fourth one, the main point of which would be the replacement of the fugue for two claviers with a new fugue, more suitable to its function as closure of the whole cycle.44

The Third Version of The Art of Fugue was thus fully engraved with the exception of the fugue for two claviers, which occupied the 14th position in the collection. This means that the idea of yet another new plan occurred to Bach no later than the time in which the first 13 counterpoints had been engraved. It is even possible that Bach managed to warn the master engraver not to engrave this fugue, which would be replaced by a new one. If this is the case, then this fugue was missing not only from the engraving plates, but also from the set of proofs.

Notes

1 The Third Version is evident in the Original Edition. However, the first part of this chapter deals with the plan that predates the printing of the edition.

2 The symbolic aspect of this structure is discussed in Chapter 20.

3 ‘Dieses letzte Werk Bachs ist im Grunde nur eine einzige Riesenfuge in fünfzehn Abschnitten’ [In reality this last work of Bach’s is a single gigantic fugue in fifteen sections.] Philipp Spitta, Johann Sebastian Bach, vol. 2 (Leipzig, 1880), p. 682. English translation in Philipp Spitta, Johann Sebastian Bach: His Work and Influence on the Music of Germany, 1685–1750. Translated by Clara Bell and J.A. Fuller-Maitland, (London, 1899), vol. 3, p. 203.

4 Unlike the two previous versions, the serial number of each fugue in the following discussion, except for the first few annotations that describe the transition (see note 6), is marked by Arabic numerals as they appear in the Original Edition.

6 The Roman numerals (i–iii) denote the fugues from the Autograph, and the Arabic numeral 4—the new fugue composed for the Third Version of The Art of Fugue.

7 Beyond the creation of a set of four fugues, there may have been another reason, perhaps even more essential, for this exchange. This will be discussed in Chapter 15.

8 The pairing of fugues iii and iv was based, mainly, on the juxtaposition of the original and inverted theme and on its transformation to a dotted rhythm. The latter was expressed not quite convincingly because the similarity between ‘small dotted rhythm’ and ‘large dotted rhythm’ is not easily identified by ear.

9 These terms usually relate to canons, where the first risposta states the theme in augmentation (a quarter note becomes a half note), and the second—in double augmentation (the quarter note becomes a whole note). In the exposition of fugue viii the bass part states the theme in double augmentation.

10 The order in which the contrasting types of dotted rhythm appear echoes the affinity between the themes of fugues iii and iv of the Autograph: the ‘microdotting’ in fugue vii stands for ‘small dotting’, while in fugue viii—in contrast, the ‘small dotting’ is responsible for the ‘microdotting’.

11 A fugue on a cantus firmus presents a certain paradox: strictly speaking, it is a simple fugue with an additional accompaniment (if the cantus firmus is stated only once) or with consistent countersubject (if the cantus firmus appears several times). In both cases, two themes participate in the fugue, making it possible to regard it as a ‘double’ fugue, that is, a fugue with two themes.

12 This fugue is usually referred to in Bach literature as BWV 1080/131, 2.

13 ‘Die letzteren sind Arrangements jener beiden dreistimmigen Fugen’ [Both these last (Spitta means the two versions of the fugue for two claviers—A.M.) are arrangements of those two three-part fugues …]. Spitta, Johann Sebastian Bach, vol. 2, p. 677. English translation in Bell and Fuller-Maitland, vol. 3, p. 198.

14 In 1841, when the Autograph was deposited in the Berlin Royal Library.

15 The view that the second clavier in this fugue (xvi) was needed to support an earlier variant (the second mirror fugue, 132, which was too difficult for performance) was voiced as early as in Philipp Spitta’s book: ‘…Welche (zwei Fugen für zwei Claviere) zum Theil sehr schwer, je nach Bachscher Art gar nicht zu spielen sind’ [portions of this are very difficult, nay, impossible, to play] and then also ‘auch schon durch die Einführung eines zweiten Claviers aus dem Stil des Ganzen herausfallt’ [… while the introduction of a second clavier radically alters its style and character …], Spitta, Johann Sebastian Bach, vol. 2, pp. 677–8. English translations in Bell and Fuller-Maitland, vol. 3, p. 198.

16 Several scholars think that Bach planned the fugue for two claviers as a separate arrangement for music-making sessions with his sons and students. For example: ‘Bach hat sie vielleicht für das Zusammenspiel mit einem Schüler geschaffen—etwa für seinen 1732 geborenen Sohn Johann Christoph Friedrich oder für Johann Christoph Altnickol, der in der Zeit zwischen 1745–1748, also genau in der mutmaßlichen Entstehungszeit von sowohl Contrapunctus 13 als auch der ‘Fuga a 2. Clav:’ von Bach unterweisen wurde.’ [Bach perhaps created it for the interaction with a student—maybe for teaching his son Johann Christoph Friedrich, born in 1732, or for Johann Christoph Altnickol, between 1745 and 1748, exactly the composition time of both Contrapunctus 13 and the fugue for two claviers.] Pieter Dirksen, Studien zur Kunst der Fuge von Joh. Seb. Bach: Untersuchungen zur Entstehungsgeschichte, Struktur und Aufführungspraxis (Wilhelmshaven, 1994), p. 55.

17 Hofmann, NBA KB VIII/2, p. 22, note 12.

18 ‘der fragliche Bogen dem Hauptmanuskript nicht ursprünglich angehört hat und nachmals von der Berliner Bibliothek zu Recht separiert worden ist.’ […the sheets in question initially did not belong to the main manuscript (of The Art of Fugue—A.M.) and were rightfully separated from it.] Ibid.

19 Johann Mattheson writes in a chapter dedicated to double counterpoint: ‘Nunmehr aber kommt die Reihe an solche Contrapuncte, die nach einem gewissen Intervall benennet werden, und deren drey sind: Nehmlich 1) der doppelte Contrapunct all’Ottava, 2) der alla Decima, und 3) der alla Dodecima’ [Now, however, we turn to a series of such counterpoints, which are named for one certain interval, and of which there are three: namely 1) double counterpoint all’Ottava, 2) alla Decima, and 3) alla Dodecima] Johann Mattheson, Der vollkommene Capellmeister (Hamburg, 1739), p. 422. Translation based on Ernest C. Harriss Johann Mattheson’s Der volkommene Capellmeister: A Revised Translation with Critical Commentary (Ann Arbor, 1981), p. 777. The same kinds of counterpoint are described in Johann Joseph Fux’s Gradus ad Parnassum and Angelo Berardi’s Documenti armonici. All three texts existed in Bach’s personal library.

20 [The dec[eased] Papa ordered to engrave on this page [:]Canon per Augment. in Contrapuncto all octava, but on the proof printout he erased it and wished to leave it as follows]

21 This preference is applied in most cases. For example, in the Canonic Variations BWV 769 (the variant of the autograph), where the cycle is concluded by a canon in augmentation and inversion; the 14 canons on the bass of the Air from the Goldberg Variations, BWV 1087, end with a canon in augmentation and inversion; the beginning of the Quodlibet in BWV 988 looks as such a canon in which both proposta and risposta are introduced simultaneously; finally, the penultimate of the six thematic canons from the Musical Offering BWV 1079 is, too, a canon in augmentation and inversion.

22 See for example: Wolff, Johann Sebastian Bach: The Learned Musician, p. 434; Schulenberg, The Keyboard Music, pp. 348–9; Schwebsch, J.S. Bach und Die Kunst der Fuge, pp. 310–23; Dirksen, Studien zur Kunst der Fuge, p. 20.

23 This is one of the mysteries of The Art of the Fugue. It will be discussed in Chapter 11.

24 To the best of our knowledge, all recent studies concerning the history of The Art of Fugue’s printing essentially state that the fugues and canons were intentionally engraved in an order different from the one present in the printed edition. ‘Three phases’ of the engraving process are usually discussed. The first phase (1748/1749): fugues 1, 3, 4, 11, 121,131 and the four canons; the second phase (1749): Fugues 2, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 122 and 132, and the third phase (1751) 10a, the fugue for two claviers, the unfinished concluding fugue and the ‘posthumous choral’. See, for example, Wiemer, Die wiederhergestellte Ordnung in Johann Sebastian Bachs Kunst der Fuge: Untersuchungen am Originaldruck (Wiesbaden, 1977), p. 50; Butler, ‘Ordering Problems’, p. 58; Schleuning, Johann Sebastian Bachs ‘Kunst der Fuge’ (München, 1993), p. 169.

26 The Autograph is considered here as a clean manuscript containing materials of both the First and the Second Versions of The Art of Fugue.

27 As a result, the following pieces were modified: fugues i, ii, iii and vi (and to a lesser degree—iv, v, viii, x, xi and xviii) and the Canon in Augmentation (xv). Reworking fugue vi (in the Third Version of The Art of Fugue it is number 10) required copying it from scratch. Therefore, its inscription in P 200 could not be used for the Third Version.

28 Fugues ii, iii, iv, v, vi, x and xi changed positions in the Third Version.

29 Fugue 4, the canon at a 10th and the canon at a 12th were composed specifically for the Third Version.

30 The only exception is the last canon (in augmentation and inversion), which is written on three pages. This was not as essential for the order, because it occupied the last position in the cycle’s Third Version.

31 The process that will bring these fugues change in internal ordering is discussed and analysed in Chapter 11.

32 J.A. Fuller-Maitland, ‘A Set of Bach’s Proof-Sheets,’ Sammelbände der Internationalen Musikgesellschaft, II/4 (August 1900): p. 643.

33 Gregory Butler dedicated a special section to the problem of proof copies. Butler, Bach’s Clavier-Übung III, pp. 65–71.

34 Manfred Tessmer (ed.), NBA KB IV/4, Dritter Teil der Klavierübung (Kassel, 1974), pp. 17 and 19. A7 is kept in the British Library in London (shelfmark Hirsch III.39) and A15 in the Oesterreichische Nationalbibliothek in Vienna (shelfmark Hoboken 1.5.Bach.33).

35 Butler, Bach’s Clavier-Übung III, p. 66.

38 The exact nature of Bach’s commission to Schübler, for which this sum was paid, is not indicated. However, according to preserved documents, at that time Schübler’s only commision from Bach was The Art of Fugue. See Wolfgang Wiemer, ‘Johann Heinrich Schübler, der Stecher der Kunst der Fuge,’ BJ 65 (1979): pp. 75–95.

40 Butler, Bach’s Clavier-Übung III, pp. 65–72.

41 Wolff, Bach: Essays, p. 270. Wolff writes about the set of engraver copies, using the word copy in singular: ‘engraver’s copy (principal portion)’. (p. 269).

43 This folder also contained the score of the church cantata by Johann Friedrich Fasch. This may refute Wolff’s thesis because the traces of vertical folding marks could be made by Fasch’s cantata. The cantata, however, became part of the folder many years after The Art of Fugue had been published, probably after 1765. In addition, the note, written by Emanuel’s hand ‘Herr Hartmann hat das eigentliche’ [the original is at Mr Hartmann’s] was attached to this file during the period when materials from The Art of Fugue were already inclued in it. Emanuel’s note will be discussed below more in detail.

44 The note ‘und einen andern Grund Plan,’ written on the verso of page 5 of P 200/1–3 may provide an additional clue, which is discussed in Chapter 18.