No Bach scholar has ever seen the title page of The Art of Fugue or, for that matter, even the name of the work written in Bach’s own hand. This is why it is still uncertain who, in fact, conceived of the title. The problem first emerged when Philipp Spitta raised doubts, which later spread to other Bach studies,2 as to whether the title Kunst der Fuge came from Bach himself.3 We do know that the name Kunst der Fuge was altered throughout the formation process of the work as a whole. The reasons for these alterations, once revealed, might cast a light on the puzzle of the title’s authorship.

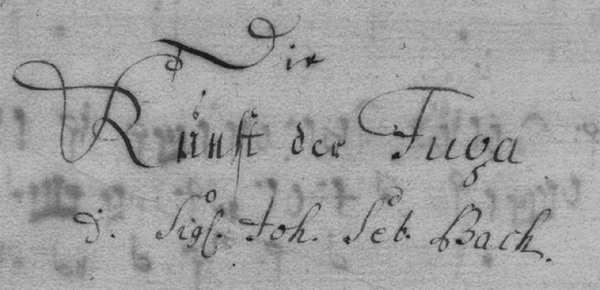

Four variants of the title are known today: two handwritten and two in print. The earliest of those preserved was written by J.C. Altnickol (Figure 15.1).4

The inscription reads: Die / Kunst der Fuga / d. Sig[?] Joh. Seb. Bach.5

The next, chronologically, is probably the other handwritten variant, inscribed by Johann Christoph Friedrich Bach (?)6 and Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach on the grey-blue cover of the folder that contained all three supplements to P 200 (Figure 15.2).

The inscription can be dated sometime between 1748 and 1752. It reads: [Die] Kunst / der Fuge / Von J[.]S.B.7 The first printed variant of the title appears on the cover page of the 1751 edition (Figure 15.3).

It reads: Die / Kunst der Fuge / durch / Herrn Johann Sebastian Bach / ehemahligen Capellmeister und Musikdirector zu Leipzig. The title page of the 1752 edition has exactly the same wording, with only layout differences: here the word ‘Herrn’ is positioned in a separate line and is written all in capital letters; the words ‘zu Leipzig’ are separated in a last line: Die / Kunst der Fuge / durch / HERRN / Johann Sebastian Bach / ehemahligen Capellmeister und Musikdirector / zu Leipzig.

Each of these four title page variants has unique traits that deserve discussion. First, however, the possibility that the title itself, Die Kunst der Fuge, may have been invented not by Bach but by someone else, should be contemplated. The feasibility that by 1744, after several years of composing this new work, encircled by family members, pupils and friends who knew his work, and often copied parts of it, he had not given it even a temporary name, is very low to nil. The starting premise, therefore, is that J.S. Bach did have some kind of a working title, with which those in his close circle were probably familiar. Assuming that, giving a different title to this work without the author’s consent, is hard to imagine. Therefore, the working assumption of this study is that Bach himself gave The Art of Fugue its title.

Still, the title of a work is not synonymous with the title page. The latter has its own structure, on which Bach bestowed a special significance that often transcended the literal meaning of the title itself. Nevertheless, the fact is that the title page of the fair copy of The Art of Fugue (P 200) remained blank for a long time (the exact period has not been established yet).

It has been established, though, that Bach began his work on The Art of Fugue in ‘about 1740 at the latest, more likely the end of the 1730s.’8 The beginning of Bach’s cooperation with Altnickol is documented in the composer’s letter of recommendation on the latter’s behalf, written in September 1745.9 It appears, therefore, that the recto of the Autograph’s first page remained blank for several years (from about 1740)—an interval of time that seems rather strange. What might have been the reason for this delay? A comparison of Altnickol’s inscription with the other three might provide an answer.

This title is organised in three lines:

Die

Kunst der Fuga

d. Sig[?] Joh. Seb. Bach.

The unnecessary juxtaposition of German and Italian, quite uncommon for a title page, immediately attracts attention. Its contrast with the three other variants of the title page, which are written exclusively in German, underscores the peculiarity of this combination. In fact, it had led several scholars to doubt the authenticity of the title.10 What might have prompted this mixing of languages?

A look at paragrammatic compositions that were widespread in German culture throughout the seventeenth century and the first half of the eighteenth century may provide an explanation.11 Figure 15.4 shows a fragment from the Poetischer Trichter [Poetic Bullhorn] by Georg Philipp Harsdörfer.12 It features a paragrammatic composition where the words ‘Jesus ist Christus’ equal in their numerical value (218) to ‘unser Helfter und Heile,’ thus creating a pair of symbolic synonyms.

There are instances of Bach’s use of similar techniques. It has been confirmed that Bach paid serious attention to paragrammatic constructions as early as the mid-1730s. In his later works, he applied this technique extensively, especially in the Mass in B minor (and most clearly in the Symbolum Nicenum).

The First Version of The Art of Fugue, finalised in the manuscript P 200, was created between 1740–42 and 1746.13 The fact that paragrammatic compositions from that period have been frequently spotted in his cantatas and oratorios does not exclude their presence in instrumental music, too, where the compositional evolvement is not necessarily related to a text. In such cases, paragrams would feature in the title and the title page.

The length of the title supports attempts at its interpretation as a paragram. In comparison with other works by Bach, such as the Inventions, Sinfonias or The Well-Tempered Clavier, which feature longer titles, a longer title would be expected here, too, particularly since The Art of Fugue is such a fundamental work.14 Yet, the first two variants of the title are brief.

It is most likely that Bach, always very particular with regard to signs and symbols of his own name in different variants (Bach = 14; J.S. Bach = 41; Johann Sebastian Bach = 158) would not have resisted the temptation to exploit the numerical proximity of the following:

Die Kunst der Fuge = 162

Johann Sebastian Bach = 158

Only four digits separate the title and the composer’s name, and Bach did not miss this opportunity to create here, too, a pair of symbolic synonyms. The process of matching is not simple: one has not only to match digits, but also to retain the meaning of the text. Bach found a brilliant solution: in the word ‘Fuge’, he changed just the last letter, resulting in ‘Fuga,’ the Latin (and Italian) form of the same term. This resulted in a rather odd linguistic combination, particularly when compared with the more familiar later versions of the title where the spelling is entirely German. However, although not common, such spelling is acceptable as an ‘admissible atypicality’, widely spread among encrypted Baroque inscriptions. The composer, therefore, arrived at the unique title on the cover of P 200: ‘Die Kunst der Fuga’, generating the required match:

Die Kunst der Fuga = 158

Johann Sebastian Bach = 158

The result is a typical paragrammatic composition. Interestingly, 158 is not just the numerical expression of Johann Sebastian Bach; the sum of digits in this number equals the numerical value of Bach (2–1–3–8), a fact of great importance for the composer:

(1 + 5 + 8) = (2 + 1 + 3 + 8) = 14

It is hard to imagine that such a paragram is a mere coincidence and that Bach did not notice it. On the contrary, there is reason to believe that he invested intellectual effort in matching numbers and letters. We should remember, however, that the phrase ‘Johann Sebastian Bach’ is only a suggested abstraction, a possible reference whose numerical value the composer could have had in mind for the paragram of the first two lines in this title page.

The above considerations encourage a similar approach to analysis of the third line of the title page. The numerical sum of its letters is 108. This number is so far away from 158 that in order to find its paragrammatic meaning one needs to look for some other principle of codification. The only datum we have, thus, at this stage, is the first expression of a possible paragram.

d. Sig[?] Joh. Seb. Bach = 108

It was Friedrich Smend who first mentioned the number ‘84’ that Bach wrote at the end of the Patrem omnipotentem in the Mass in B minor, sealing the 84 bars of the section. Taking this as a starting point, Robin Leaver proposed an analytic method, looking at the symbolic meanings encapsulated in the number of bars of each section in the Credo. Later, Anthony Newman mentions the match between the number of letters in the poetic text (84) and the number of bars in the musical text (84).15 Combining this method with our analysis of the titles of The Art of Fugue, we matched the third line on P 200’s title page with the number of bars in the first three fugues of The Art of Fugue. The reason for choosing the first three fugues is that they share an important feature: they, and only they, leave the theme rhythmically intact (starting in half notes). Their total number of bars is 111. Although the numbers do not match, and therefore there is still no finalised paragram, the difference is small:

d. Sig[?] Joh. Seb. Bach = 108

Number of bars in fugues I, II and III = 111

This small mismatch may be related to the fact that the numerical value of the title’s third line is, actually, still unclear: one sign, here replaced by a question mark, is rather indistinct and although quite visible is not easily read. Unsurprisingly, various scholars have interpreted this mark in different ways. For instance, Christoph Wolff reads it as the abbreviation as ‘di Sig.’;16 Peter Schleuning—as ‘di Sign°’,17 and Klaus Hofmann as ‘d. Sigl.’, writing the last letter in cursive script.18

Yet, another reading could be offered. In eighteenth-century German manuscript practice, this figure used to serve as a conventional abbreviation. It had the character of a capital ‘C’ in cursive Latin. The sign is derived from the initial letter of the French word coupure (a cut), marking a truncated word.19 Johann Christoph Friedrich Bach, for example, used it quite often to abbreviate certain words. For example, the word ‘Graflicher’ in his letter to the State Graf Wilhelm Schaumburg-Lippe, on May 24, 1759, written ‘grafC’ (Figure 15.5);20 the word ‘Bückeburg’, from which he wrote a letter to Breitkopf, the publisher, on November 20, 1785, is written ‘BückebC’; so is the word ‘exempel’ in another letter to Breitkopf from November 23, 1784, written ‘exemC’ and the word ‘Herrn’ in a letter, also to Breitkopf, from December 17, 1786, written ‘HC’.21 The sign ‘SigC’, therefore, probably means ‘Signor’, and the ‘d.’ marks the Italian word ‘di’ (or, to accept a further linguistic mixture—‘der’), abbreviated here for the sake of the paragram.

Interpreted as a ‘C’, the letter carries the numerical value 3, allowing the following calculation:

d. Sig[C] Joh. Seb. Bach = 111

Number of bars in fugues I, II and III = 111

The above findings indicate that what may seem at first a strange linguistic concoction of French, Italian and German abbreviations, truncations and so on is probably a result of paragrammatic games, introduced to suggest and supplement meanings to written excerpts.

Another puzzle relates to the choice of the inscription’s writer. Why was the title page not written by J.S. Bach but by another person? What prevented Bach himself from inscribing it, especially since the title page had been left blank for such a long time? The presence of Altnickol’s hand in the inscription is not coincidental: Bach needed his name to be written in the third person. Bach never referred to himself in the third person, nor did he ever write in his own hand the words Signor, Herr, or their variants in score inscriptions. The letters ‘SigC’, marking the word ‘Signor’, were needed for their numerical value. The solution might have been to ask someone else—Altnickol, in this case—to write the title in his own hand.

An understanding of the importance that Bach attached to paragrammatic constructs in his works might help in solving a question posed earlier: why was the cover of P 200 left without a title for such a long time? The many years that had passed between the completion of the work and the (paragrammatic) writing of the title might imply, at least to a certain extent, that the title somehow depended on the content of the composition itself. For example, the numbers of bars in each fugue—at least in the first three fugues—was correlated with the title inscription. It is clear, therefore, that the title could not have been finalised before at least several of the compositions in this cycle had been completed. Furthermore, it is probable that Bach’s composition of the work as a sequence of fugues and his planning of the title page as a paragrammatic construction progressed in parallel. Finally, and most importantly, if the paragram contained in the title is the result of Bach’s own work, then the title, too, should be considered as solely his.

The title page that appears on the gray-blue folder cover (Figure 15.2) was probably written by Johann Christoph Friedrich Bach between August 1748 and the end of 1749, when he left Leipzig for Bückeburg. During this period the Third Version of The Art of Fugue was created. However, the possibility that this title (albeit not necessarily its composition) might have been written later, sometime between 1750 and 1752, cannot be excluded. The title reads:

[Die] Kunst

der Fuge

Von J[.]S.B.

Any idea of linguistic mixtures is here abandoned: the whole title is in German.22 The article Die was added later, by Philipp Emanuel, probably after his father’s death, and could not reflect Johann Sebastian’s intentions. Moreover, it is unclear if the word is crossed out or underlined. The numerical value of the whole text (233, without the article ‘Die’) does not tell much. The last line is odd, too; von is written in the middle of the line, suggesting that initially it might have been intended to stand alone in the line, just like the word ‘Kunst’. The initials ‘J[.]S.B.’ look rather indecisive, more like a later addition to the line, instead of being symmetrically situated on the next line.

Like the title of the earlier version, this one is puzzling, too. Why was the title originally written here without the article ‘Die’? Was it due to some kind of structural idea or manipulation of letters and numbers? And why would Emanuel add the article ‘Die’ to the title? Was it deleted or emphasised by an underline?

The title’s brevity suggests that Bach had originally intended to present the title as a paragrammatic composition. As we see in the case with the title of the Autograph, it can be correlated with the musical text. However, the history of this whole cycle is rich with various versions of the music itself, and it is unknown to which one of them this particular title, written on the folder that contained later supplements, could relate. Given that, at this point it seems unproductive to look for the numerical sense of this title. Therefore, these and other questions related to this presentation of the title remain, for the time being, unanswered.

Most studies share the opinion that the final wording on the title pages of the 1751 and 1752 printed editions (Figures 15.3 and 15.4) belongs to Carl Philipp Emanuel. J.S. Bach usually (and especially in printed editions) wrote his title as ‘Directore Chori Musici Lipsiensis’, and never as Musikdirector, particularly not with a ‘k’. In fact, he always spelled words derived from ‘music’ with a ‘c’. Comparing the two texts, we see that they differ only in their typographic design; their wording is identical. Judging by its laconic form and its meaning, the 1751 title page recalls the two earlier handwritten titles, both lacking a detailed description of the work’s content and its purpose, stating only the title (The Art of Fugue) and the composer’s name. This peculiarity supports the assumption that J.S. Bach was fashioning paragrams.

The last line on this page introduces an additional remark mentioning the former Capellmeister and Musikdirector. This addition could not have been inscribed by Johann Sebastian: it was Philipp Emanuel who published the printed edition. The incongruities within this variant of the title result from modifications originally initiated by J.S. Bach, which Emanuel edited while preparing the work for posthumous publication, without suspecting that he might be hindering the composer’s intention. This interpretation is supported by the presence of words in the title that are uncharacteristic to both J.S. Bach and Philipp Emanuel. Any attempt to separate elements that, in all likelihood, were generated by paragrammatic intentions from those dictated by the new circumstances of a posthumous edition, should begin with a close examination of the first printed edition’s title page (Figure 15.3):

Die

Kunst der Fuge

durch

Herrn Johann Sebastian Bach

ehemahligen Capellmeister und Musikdirector zu Leipzig

Judging by the design, Emanuel added only the last line and the word ‘Herrn’ before the name of the composer, as required by the new situation.

There are several reasons to suggest that Emanuel merely edited a title that he had seen in writing at an earlier time. The first indication is the presence of the word ‘durch’. The point is that Emanuel’s title pages, regardless of the ways in which the composer is presented, or whether they are in German, French or Italian, never present the word ‘durch’ despite its being very common in titles of other contemporary composers. Moreover, the handwritten title pages by Johann Sebastian, as well as those by Philipp Emanuel, never use the word ‘durch’ in a phrase presenting the author.23 It is not likely that Emanuel would have decided to change his approach just in this case, and it would also be uncharacteristic that in the process of publishing The Art of Fugue he would concern himself with questions of paragrammatic composition. Therefore, it is improbable that the ‘durch’ came from Emanuel. If this is indeed the case, it is reasonable to deduce that the word was introduced here according to the expressed wish of J.S. Bach.24

What would the original title page have looked like? Removing from the printed title Emanuel’s probable editing, that is, anything that J.S. Bach would not write, would result as follows:

Die

Kunst der Fuge

durch

Johann Sebastian Bach

Apart from the word ‘durch’ there is nothing special in this title, which is in complete accord with the two handwritten titles. This suggests that all of the variants of the title page could have originated from only one source: the creative mind of Johann Sebastian Bach.

We turn now to other ‘admissible atypicalities’, having already determined that they are, in the title page of P 200, results of paragrammatic manipulation of letters and numbers. The insertion of the word ‘durch’, in the title page of the printed edition, might have served a similar purpose. In such a case, the presence of this word in the title acts—if not as a proof—at least as an indication to the probability of such a process.

To conclude, the proposed reconstruction of the composer’s original title page, intended for the first printed edition, is based here on three arguments:

• The four-line construct and its laconic presentation may suggest the possible presence of a paragrammatic component.

• The printed title no longer uses a German-Italian combination (the word Fuge is written in its German variant).

• This impression is reinforced by the uncharacteristic word ‘durch’ that is interpreted here as indicating paragrammatic manipulation.

A comparison between the fugues in the Autograph and the contrapuncti in the printed editions shows that, while preparing The Art of Fugue for print, Bach refashioned the fugues in certain ways. Each change is puzzling for its seeming purposelessness, and there are no signs of any connection between them.

First, Bach changed the principle of organisation of the fugues at the beginning of the cycle. Instead of the existing sequence of pairs of fugues in the original Autograph, he grouped the first four fugues and renamed them as contrapuncti. To that end, he added to the printed edition a new fugue (Contrapunctus 4) on the basic theme, without any rhythmic changes—a fugue that does not exist in the Autograph at all. Moreover, comprising 138 bars, this new fugue is disproportionally long in comparison with the first three, which appear in the Autograph as, respectively, 37, 35 and 39 bars long. Why did he need this new giant fugue, and why was it located precisely at the fourth position in the printed edition?

The transformation did not leave the first three fugues untouched: while their rhythmic values remained intact, the metre was changed from ![]() to

to ![]() a procedure that doubled the number of bars, turning out to be 74, 70 and 78, respectively. Why?

a procedure that doubled the number of bars, turning out to be 74, 70 and 78, respectively. Why?

In addition to doubling the number of bars, Bach added several bars to each of the first three fugues: four bars were added to the first fugue, two to the second one and six to the third (see Table 15.1). While we could regard these as simple corrections, a musical analysis shows that the new bars make no real difference. Each of these fugues could exist (and indeed still exists in concert practice) as it appears in the Autograph. It seems that the manuscript and the printed variants of these fugues have equal artistic value. What then could have been the reason for these inessential extensions?

Formerly, among the changes made from the Second to the Third Version, Bach had changed the ordering of the first three fugues. Fugues II and III in the manuscript changed places, respectively becoming Contrapunctus 3 and Contrapunctus 2 in the printed edition. The reasons for that were discussed in Chapter 9. However, it seems that there were some additional calculations that contributed to these modifications, summarised in Table 15.1.

While one might assume that these changes reflected Bach’s artistic concept, it is nonetheless impossible to ignore the fact that they were all, in one way or another, related to one element: the number of bars. It is quite possible that a ‘letters and numbers’ manipulation has a role here, too. The hypothetical four-line design of the title could allude to the first four fugues of the cycle (just as the three-line design of the Autograph’s title alludes to the first three fugues). The possible correspondence between the numerical value of the title’s letters (a tentative paragram) in the first printed edition and the number of bars of the first four contrapuncti in that edition25 is shown in Scheme 15.1.

This unbelievably precise correspondence could, of course, be a mere coincidence, but that would be very unlikely. Such significant changes in this part of the cycle would hardly have occurred except as a result of an intentional and sophisticated operation.

The sequence of letters in the name Bach, 2–1–3–8, as reflected in the numeric alphabet, are framed at the end of the last line: ‘Durch Johann Sebastian Bach’. They also appear, in this order, in the framed number of bars of Contrapuncti 3 and 4: [7]2, 138. The two sets (of words and numbers) end in the same way, both related to Bach’s name.

The edge of the thread is the last fugue, known as Contrapunctus 4, which did not exist prior to the first printed edition. The number of its bars, 138, disproportionately differs in scale from fugues I–III of the manuscript, which were, initially, 37, 35 and 39 bars long, respectively. Its digits, 1–3–8, strangely coincide with the three last letters of Bach’s name: A-C-H. The missing B, numerically equivalent to 2, was required just before this figure. The composer, thus, had to somehow envisage a way to manipulate the number of bars of Contrapunctus 3 to end with the digit 2. If we assume that Bach wanted to construct a paragram that matched the total number of bars of Contrapuncti 3 and 4 to 210, which is the numeric expression of ‘Durch Johann Sebastian Bach’, we would be looking for a 72 bar long contrapunctus (210 − 138 = 72), thus requiring an addition of two bars to the existing 70 of Contrapunctus 3, which is exactly what happened.

None of the original three fugues in the manuscript, with their 37, 35 and 39 bars could approach—even remotely, either by itself or in any combination—this desired number of 72. Bach’s ‘Columbus’s egg’ solution was to double the number of bars in the three first fugues by changing the metre from ![]() to

to ![]() without altering even one note. The operation rendered three contrapuncti of 74, 70 and 78 bars respectively. Since cutting any finished fugue is infinitely more time consuming than extending it, and since the digit 2 was needed at the end of the third contrapunctus, Bach picked up the only candidate for this purpose—fugue II, added two bars to it and positioned it as third in the set of four first contrapuncti. In this way he both strengthened the four-set character of this group (rather than the former pairs) and also created a numerical paragrammatic equation between text and number of bars—the total paragrammatic value of the third and fourth line in the title with the total number of bars in the third and fourth contrapuncti, with the additional meaning of his name’s letters reflected in the last group’s bar numbers.

without altering even one note. The operation rendered three contrapuncti of 74, 70 and 78 bars respectively. Since cutting any finished fugue is infinitely more time consuming than extending it, and since the digit 2 was needed at the end of the third contrapunctus, Bach picked up the only candidate for this purpose—fugue II, added two bars to it and positioned it as third in the set of four first contrapuncti. In this way he both strengthened the four-set character of this group (rather than the former pairs) and also created a numerical paragrammatic equation between text and number of bars—the total paragrammatic value of the third and fourth line in the title with the total number of bars in the third and fourth contrapuncti, with the additional meaning of his name’s letters reflected in the last group’s bar numbers.

If the above reasoning is correct, a similar match should exist between the number of bars in the first two contrapuncti and the first two lines of the text: ‘Die Kunst der Fuge’. The total of its numerical equivalent is 162. Indeed, this is exactly the sum of bars of Contrapuncti 1 and 2 in the printed edition. In order to reach the number 162 in the remaining fugue I and fugue III, which had 74 and 78, 10 more bars were required (74 + 78 = 152). Bach extended these fugues, adding four and six bars to them, respectively: the new Contrapunctus 1 has now 78 bars, and Contrapunctus 2—84 bars, a total of 162 bars.

This analysis shows that there are absolutely no changes in this part of The Art of Fugue that cannot be explained as paragrammatic constructs entailing modifications based on numerical calculations made to match the text of the title page with new bar numbers of the first four contrapuncti.

The interpretation of the title pages of The Art of Fugue (Autograph and printed editions) as paragrammatic constructs offers answers to some of the questions presented above. It also relates to the changes made while preparing the handwritten variants of The Art of Fugue toward the printed version. Without this understanding of the title pages, it would hardly be possible to supply reasonable answers to these questions. Paragrammatic constructs appear neither spontaneously nor by chance. The more elements there are in a paragram (letters and numbers), the less the probability of its being coincidental. This unavoidably leads to the conclusion that the hypothetically reconstructed title page, proposed above, most probably really existed and that the author of the paragram could only have been Johann Sebastian Bach himself.

1 This chapter is also published in Min-ad: Israel Studies in Musicology Online 12 (2014): http://www.biu.ac.il/hu/mu/min-ad/, with the kind permission of Ashgate Publishing.

2 Hofmann, NBA KB VIII/2, p. 23; Bergel, Bachs letzte Fuge; Schleuning, Johann Sebastian Bach’s ‘Kunst der Fuge; Mikhail Semenovich Druskin, Iogann Sebastian Bakh (Moscow, 1982); Jacques Chailley (ed.), L’Art de la fugue de J.S. Bach. Étude critique des sources: remise en ordre du plan, analyse de l’œuvre, au-delà des notes, vol. 1 (Paris, 1971).

3 ‘Wenn wir auch nicht sicher wissen, ob der Titel “Kunst der Fuge” von Bach selber herstammt … ’ Philipp Spitta, Johann Sebastian Bach, vol. 2 (Leipzig, 1880), p. 678.

4 The title page has an additional inscription, ‘in eigenhändiger Partitur’, written in parentheses and located about an inch lower than the figure shown here. This inscription was added decades later, after the death of C.P.E. Bach but prior to 1824, by one of the subsequent owners of the manuscript, Georg Poelchau (1773–1836).

5 The question mark in square brackets marks an unclear sign, which will be discussed later.

6 Christoph Wolff identified the title as ‘inscribed by Johann Christoph Friedrich Bach’. Wolff, Bach: Essays, p. 267–68. However, Klaus Hofmann classified the title as written ‘von unbekannter Hand’. Hofmann, NBA KB VIII/2, p. 48.

7 The [Die] in square brackets was written by C.P.E. Bach. See Hofmann, NBA KB VIII/2, p. 48.

8 Wolff, Bach: Essays, p. 271.

9 BD I/81, pp. 148–9; NBR, no. 240, pp. 224–5.

10 Bergel, Bachs letzte Fuge, p. 57; Schleuning, Johann Sebastian Bachs ‘Kunst der Fuge’, p. 179.

11 The concept of paragram is used here as defined in Ruth Tatlow’s fundamental PhD dissertation ‘LUSUS POETICUS VEL MUSICUS, Johann Sebastian Bach: The Baroque Paragram and Friedrich Smend’s Theory of a Musical Number Alphabet’ (London: King’s College, 1987) and in her book Bach and the Riddle of the Number Alphabet (Cambridge, 1991). She expands on these ideas in several of her later articles, such as ‘Collections, bars and numbers: Analytical coincidence or Bach’s design?’ in Ruth Tatlow (ed.), Understanding Bach, 2 (2007): pp. 37–58, and ‘Bach’s Parallel Proportions and the Qualities of the Authentic Bachian Collection’, in Reinmar Emans & Martin Geck (eds.), Bach oder Nicht Bach: Bericht über das 5. Dortmunder Bach-Symposion (Dortmund, 2009), pp. 135–55.

12 Georg Philipp Harsdörfer, Poetischer Trichter, Die Teutsche Dicht- und Reimkunst ohne Behuf der Lateinischen Sprache. Dritter Theil (Nürnberg, 1653), p. 72. Harsdörfer (1607–58) was a poet and scholar, the author of 50 volumes of poetry and other works and a member of several literary societies, one of which he founded.

13 Yoshitake Kobayashi, ‘Zur Chronologie’, p. 70.

14 For example, the full title of The Well-Tempered Clavier reads: Das Wohltemperirte Clavier. oder Præludia, und Fugen durch alle Tone und Semitonia, so wohl tertiam majorem oder Ut Re Mi anlan/gend, als auch tertiam minorem oder Re Mi Fa betreffend. Zum Nutzen und Gebrauch der Lehrbegierigen Musicalischen Jugend, als auch derer in diesem studio schon habil seyenden besonderem Zeitvertreib auffgesetzet und verfertiget von Johann Sebastian Bach. p.t: Hochfürstlich Anhalt-Cöthenischen Capel-Meistern und Directore derer Camer Musiquen. Anno 1722 [The Well-Tempered Clavier // or // Preludes and Fugues / through all the tones and semitones / both as regards the tertia major or Ut Re Mi / and as concerns the tertia minor or Re Mi Fa / For the Use and Profit of Musical Youth Desirous of Learning / as well as for the Pastime of those Already Skilled in this Study / drawn up and written by Johann Sebastian Bach / p.t: Capellmeister to His Serene Highness the Prince of Anhalt-Cöthen, / and Director of / His Chamber Music / Anno 1722].

15 Friedrich Smend, Edition of the B minor Mass by J.S. Bach, NBA KB II/1 (Kassel, 1956), p. 333; Robin A. Leaver, ‘Number Associations in the Structure of Bach’s CREDO, BWV 232’, BACH, 3 (1976): p. 17; Anthony Newman, Bach and the Baroque: European Source Materials from the Baroque and Early Classical Periods, with Special Emphasis on the Music of J.S. Bach (Stuyvesant, NY, 2nd edn 1995), p. 196.

16 Wolff, Bach: Essays, p. 267.

17 Schleuning, Johann Sebastian Bach’s ‘Kunst der Fuge’, p. 179.

18 Hofmann, NBA KB VIII/2, p. 23.

19 The capital C was used to mark truncated words especially in eighteenth century epistolary and formal etiquette, which was largely based on French. The term is also used to mark a cut in music or for the abbreviation of neumes. The author thanks Olga Blyoskina for this information.

20 The original letter is kept at the Niedersächs Staatsarchiv, Bückeburg (Shelfmark F2 Nr. 2642).

21 All three letters to Breitkopf are kept at the archive of Breitkopf und Härtel.

22 Although the last letter in the word Fuge may remind one of the letter ‘a’ in modern Latin script, here the whole inscription is performed in Gothic cursive, where it is definitely an ‘e’.

23 A similar occurrence is found in Bach’s composition Musikalisches Opfer (BWV 1079). Bach never used the term ‘ricercar’ for his fugues, while this term served as a synonym for ‘fugue’ in Germany of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. The only time Bach did so was when he needed to work with words, such as to compose an acrostic, as in ‘Regis Iussu Cantio Et Reliqua Canonica Arte Resoluta’. It is clear that the word ‘fugue’ did not fit that task. See Anatoly Milka, Muzykal’noe prinoshenie I.S. Bakha: k rekonstruktsii i interpretatsii [J.S. Bach’s Musical Offering: toward a reconstruction and interpretation] (Moscow, 1999), pp. 177–92; Milka, Iskusstvo fugi’ I.S. Bakha: k rekonstruktsii i interpretatsii [J.S. Bach’s The Art of Fugue: toward a reconstruction and interpretation] (Moscow, 2009), pp. 397–400.

24 The word ‘durch’ before the composer’s name carries a nuance of formality and high literary style, where official solemnity had to be highlighted. Bach used it only in cases that had to do with members of royal families or some special municipal event. Even in such rare instances, the word appeared only in the printed title pages. One example is Cantata BWV 71, composed in 1708 for the election of the magistrate of Mühlhausen in Thuringia; another example is in the Drama per Musica, BWV 214, composed for the birthday of Maria Josepha, the Queen of Poland and the Court Princess of Saxony, on December 8, 1733.

25 Olga Kurtch presented this analysis in her ‘Ot pomet kopiistov’, pp. 79–81.