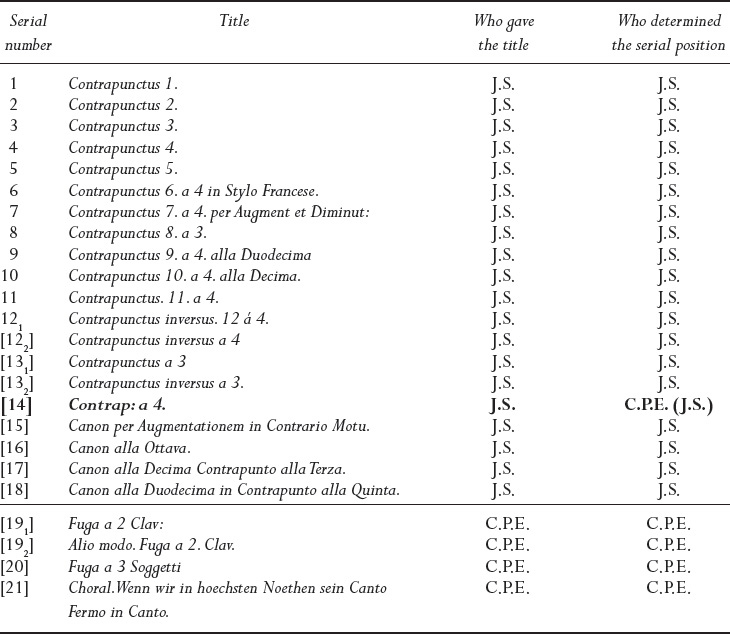

Table 13.1 Plan of the Original Edition

Several features of the Original Edition seem odd and demand interpretation. All of these peculiar traits carry important information about the construction of the edition by Philipp Emanuel as well as about the shape that his father gave to The Art of Fugue prior to his death.

Philipp Emanuel paid careful attention to every piece of information left in the materials related to the composition, such as the work’s title, its musical text and even the order in which the music sheets had been stacked. Striving to follow Johann Sebastian’s idea as closely and precisely as possible, he made independent decisions only where it was absolutely necessary.

The sequence of pieces in the Original Edition (shown in Table 13.1) presents a practically indisputable first half, with pieces numbered consecutively up to Cp12. The presence of this numbering led to a consensual impression that in the process of preparing The Art of Fugue for publication J.S. Bach controlled the engraving and the order of pieces until this point.

Bearing in mind the hypothesis that there were four versions of The Art of Fugue, as well as the view that Bach proofread the Third Version that he was preparing for publication, it is easy to realise that this version is visible in the Original Edition as the first 18 pieces. The completion of the Third Version in the Original Edition is represented in Table 13.1 by a solid line, while the serial numbers marking the order of pieces, absent in the Original Edition, are written within square brackets.

In the 14th position appears, however, what became ‘redundant material’: the Contrap: a 4., which Bach remodelled for the Third Version as Cp10, only to completely remove it from the cycle at a later stage. According to his assumed plan for the Third Version, the 14th piece should have been the fugue for two claviers. However, for the Fourth Version Bach intended to replace it with the new quadruple fugue. It was Emanuel who decided to include Contrap: a 4. in the Original Edition. Thus, in Table 13.1, under the column ‘who determined the serial position’, this piece is marked as positioned by both Carl Philipp Emanuel and Johann Sebastian.

The scholarly conviction that Bach controlled the order of the pieces up to Cp12 is based on the fact that these pieces carry serial numbers. This implies that Emanuel could have based his sequencing decisions on only these first 12 numbers, and that since there is no numeration after Cp12, all the remaining pieces could follow in a random order.

However, if the Third Version was completed, then all its engraved plates, the titles of the pieces and their serial numbers (except for the fugue for two claviers) were settled, too. Remembering that the canons, unlike the contrapuncti, were not numbered (because they were not included in the first 14 pieces, the number symbolising Bach’s name), only two pieces were left unnumbered in the Original Edition, Cp[13] and Cp[14], the latter supposedly the quadruple fugue that reached Emanuel not only unnumbered and untitled, but also unfinished; that is, not Cp[14] but Cp[14F]. As for Cp[13], the lack of numeration here can be explained by a closer examination of the titles Cp12 and Cp[13]. It is not by chance that the number 12 was inscribed just on the title of the first half of the mirror fugue (the rectus) and is absent from its second half (the inversus). Figure 13.1 shows the titles of these contrapuncti as they appear in the Original Edition:

An analysis of these inscriptions reveals several points:

• In the first inscription, the number 12 was inserted with some difficulty into a relatively small space (6 mm) between the words inversus and á 4, an insertion made, in all likelihood, after the inscription of the title.

• The same space in the three remaining titles is even smaller: 2.5, 5 and 2 mm respectively.

• The lack of numeration of these mirror fugues may not have been due to the lack of space as much as for their frequent permutation by Bach during the last stage of composition.

• By implication, it is therefore likely that the number 12 here functioned rather as a ‘custus’, connecting the group of mirror fugues with the numeration sequence of the first group of contrapuncti.

In other words, it seems that the contrapuncti listed in Table 13.1 above the solid line represent the Third Version of The Art of Fugue, and those listed below the line are those added by Philipp Emanuel. The difference is clear. In the first part, J.S. Bach’s original titles are preserved; the titles in the second part, on the other hand, were prescribed by Emanuel, who also intervened in the general title of the work. Fugues number 19 and 20 (the two fugues for two claviers and the Fuga a 3 Soggetti) carry no titles in the Autograph, yet Emanuel could not send them to print untitled. Nevertheless, when the titles above the solid line in the table are compared with those below it, Emanuel’s efforts to show the change of hands in the Original Edition are apparent.

Another indicator of this division can be seen in the metric and rhythmic differences between the last four pieces and those preceding them.

A first oddity is seen in the uniquely abbreviated title. This abbreviation could not be Emanuel’s because he was so careful to preserve intact anything that was made by his father. He would not, by his own initiative, add the title Contrapunctus to any piece or transform it even by way of abbreviation. The fact that he had never done so in similar cases only substantiates this assertion.1 Therefore, he would name Contrap: a 4. neither a ‘contrapunctus’ nor a ‘fugue’. If this particular title, in its abbreviated form, is present in the Original Edition, it means that Emanuel had seen the words Contrap: a 4. written in exactly such a manner: the inscribed title must have been done by Johann Sebastian.

Contrap: a 4., which is based on the sixth fugue in the Autograph, presents the original rhythmic values doubled, (just as Cp10, which was derived for the Third Version from the same fugue’s countersubject, has its original rhythmic values doubled). This trait, which strengthens the similarity of Contrap: a 4. to Cp10, is an exception. Since it is quite clear that Emanuel would not bother to transform rhythmic values and/or metre, preferring to leave a variant in its original form, the fact that Contrap: a 4. is written in rhythmic augmentation suggests that it reached Emanuel precisely in this form.

Another peculiarity is apparent in the position of Contrap: a 4.: right after the second mirror fugue and before the Canon in Augmentation and Inversion.2 Beyond its awkward position in the sequence, this piece is mostly a repetition of Cp10 and therefore should not have been included in the final version at all. Regardless of the fact that the scholarly literature about The Art of Fugue has noticed this, Emanuel could not help but see how illogical such an insertion would be and subsequently remove it from the series or admit that he did not understand this point in his father’s compositional conception by simply accepting the order of pieces as they were found in the stack of proofs. However, that was the position reserved, in the Third Version, for Cp[14] (the fugue for two claviers). How, then, did a copy of Contrap: a 4. arrive in that position in the stack?

Studies of the Original Edition and the engraving style show that the engraver copy of Contrap: a 4. was produced after Bach’s death, during Emanuel’s preparation of The Art of Fugue for print. It looks odd, because all of the contrapuncti, from 1 to [13] and also the four canons were engraved while Johann Sebastian was still alive, forming the Third Version: a full set of proof copies for the future printing of The Art of Fugue. However, in the whole set there was no proof copy of Contrap: a 4. Had such a copy existed, this fugue would be printed in the Original Edition from a copper plate, engraved while Bach was still alive and not after his death. This means that the musical text of Contrap: a 4. existed within the set of the musical materials, but as a manuscript (a handwritten copy) and not as a proof copy. This is why, following Emanuel’s instructions, Contrap: a 4. had to be especially engraved for the Original Edition.

At this point, however, it is still unclear why the fugue for two claviers (Cp[14]) was missing from the proof copies set of the Third Version, and how the manuscript of the formerly discarded Contrap: a 4. appeared among the proof copies in its stead. Further, while in the Third Version the fugue for two claviers occupied this place, in the Fourth Version it was removed from this position by Johann Sebastian in order to be replaced by the new, quadruple fugue (which does appear in the Original Edition in its unfinished form and under the title Fuga a 3 Soggetti).3

It seems that the strange insertion of Contrap: a 4. reflects a particular moment in the materialisation of the Fourth Version. The fugue for two claviers was removed; in its stead should appear the new fugue, which was still incomplete. Contrap: a 4. was thus inserted as a temporary bookmark, indicating the position of a still missing proof copy. This fugue is basically a recycled piece of used paper that temporarily marked the place where the closing fugue should have been inserted. The fact that Contrap: a 4. did not look like a proof copy, but rather like a fair copy, different from the other proof copies in the stack, supports this interpretation. In this particular context it clearly ‘does not belong here’: something else should be positioned at this particular location.

Contrap: a 4. occupies a special place in The Art of Fugue’s printing history. It was not strictly added by Emanuel to the printed version of the composition, because it was already present in the set, as a handwritten copy, among the proof copies left by his father. While Sebastian did not intend to include this contrapunctus in the final version, it was nevertheless physically present there, placed by J.S. Bach’s very hand. This was probably the reason that Emanuel did not move it to another position nor remove it from the cycle, but left it exactly in the position where it was found.

The fugue for two claviers was removed from the Autograph. The bifolio was torn, separating the pair of mirror fugues, and recorded as P 200/1–2.4 This fugue was formerly a part of the cycle’s Third Version but was extracted from it and replaced by the new, quadruple fugue. If indeed this is the copy that was excluded by the composer from the cycle’s Fourth Version, it was not engraved. Emanuel had to prepare it from scratch. An analysis of the Original Edition’s engraving shows that this is exactly what happened. While doing this, Emanuel did not dare to write it in double rhythmic values, although he surely could not help seeing the similar case, Cp[13], where Johann Sebastian reworked the fugue from the Autograph precisely in this way.

The quadruple fugue reached Emanuel unfinished, without closure, in a two-stave clavier setting (P 200/1–3). Naturally, he could not know what position within the cycle it was supposed to occupy, but its unfinished state might have suggested that it should be the last piece. Indeed, this is where he positioned it in the Original Edition and how he described it in the announcement of the subscription from May 7, 1751. In all likelihood he had to commission a special engraver copy of this fragment, interpreted from the clavier layout in the Autograph into an open score layout. This arrangement was mandatory, because Emanuel could not include in the Original Edition just one piece that was not yet ready in an open score layout.5

However, Emanuel made his mark on the titles of the three pieces that were added to the Third Version and positioned at the end of the Original Edition. The title Contrapunctus and numbering were missing from the following three fugues (the two mirror fugues for two claviers and the Fuga a 3 Soggetti).

Emanuel was not aware that the fugue for two claviers should not be part of The Art of Fugue’s final version. To add it to the Original Edition he would have needed a title and a number. However, since it was not part of the Third Version stack, he would not have used the term Contrapunctus. He thus compromised on the most general and obvious feature of the piece: it was a fugue, and it was written for two claviers, and consequently titled Fuga a 2. Clav. Moreover, in its inversus, Emanuel went as far as to avoid pointing at the inversion, although he surely understood that this fugue continues the compositional logic of the previous mirror fugues. He circumscribed himself into an even more general term: alio modo, which can be understood as the same, but in another way.

As for the ‘unfinished’ fugue, Emanuel did not envision its position, although he (mistakenly) assumed, judging by the documents he had available at the time, that it should be the last in the cycle. As P 200/1–3 it does not carry a serial number, pagination or title. As with the fugue for two claviers, Emanuel neither called it Contrapunctus nor gave it a number, although the general logic of the cycle would have allowed it.6 Here, too, he indicated only the features of which, at the beginning of 1751, he was completely certain and which he published in press: he saw a fugue with three subjects and cautiously titled it Fuga a 3 Soggetti.7

An analysis of Philipp Emanuel’s steps throughout the publication process of The Art of Fugue shows that he acted with great sensitivity to questions of restoration and authenticity. Like a skilled curator he avoided, as much as he could, any intervention in the composer’s conception of his work. He broke this rule only when conditions compelled him to introduce his own marks, and even then he did it in such a way that his contribution was clearly distinguishable from the composer’s. Although his professional competence and knowledge of Bach’s style surely enabled him to realise that these additional pieces were indeed contrapuncti, and he could easily organise them in a numerical order, he chose to take no responsibility over either nomination or numeration.8

Emanuel’s attitude toward the restoration of The Art of Fugue in the Original Edition allows a hypothetical reconstruction of the material that was available to him before the publication of the work, as well as a delineation of what he did for the publication. These facts suggest that he received the materials of The Art of Fugue as a set of proof copies (or, although much less likely, engraver copies), after they had been reviewed by his father and stacked in a certain order.

This given set of pieces, in that particular order, constituted the final version of The Art of Fugue,9 as determined by Johann Sebastian, with one exception: the place where Bach temporarily inserted a simple fair copy of Contrap: a 4., which was planned for the closing quadruple fugue. Emanuel, however, left the ill-fated Contrap: a 4. in the cycle, obediently following the received order of pieces and preserving it in the Original Edition.

The main protagonist in this story was the quadruple fugue that should replace the fugue for two claviers which occupied that position in the Third Version. Indeed—the three pieces that in a way did not belong to the Third Version of The Art of Fugue (Contrap: a 4.; the fugue for two claviers and the quadruple fugue) were still connected by the same thread: they were steps toward the cycle’s unfinished Fourth Version. However, on the way toward the Fourth Version, the fugue for two claviers was removed, while the quadruple fugue, which should be positioned in that spot, was not yet completed, and the placement was thus temporarily marked by the ‘bookmark’ of Contrap: a 4.

It is possible that two manuscripts were later added to this set: the fugue for two claviers and the quadruple fugue, most probably in the same order in which they were to be included in the Original Edition.10 To these—now by his own initiative—Philipp Emanuel added the choral Wenn wir in hoechsten Noethen sein, always—in the announcement of the subscription and in other documents—pointing out that it was an arrangement composed by Johann Sebastian but external to The Art of Fugue. Moreover, Philipp Emanuel and, following him, Marpurg highlighted this point in all the documents, using such words as ‘addition’ (Anhang), ‘supplemented’ (beigefügten), ‘added’ (zugefügte). This is yet another proof of the careful attention with which the son respected the will of his father.

1 The fugue for two claviers and the ‘unfinished’ fugue have no titles in the Autograph. Emanuel thus used in the titles the obvious term, the fact that they were fugues.

2 The position of Contrap: a 4. does not follow the logic of the cycle either in relation to the preceding pieces or to the following ones.

3 This is actually the quadruple fugue. The autograph that Emanuel received (P 200/1–3) did not have a fourth theme. It was only later that Gustav Nottebohm showed that there were four themes (see Nottebohm, ‘J.S. Bach’s letzte Fuge’). Indeed, the definition of this fugue is complicated: there is no fourth theme in the exposition: it appears as a cantus firmus in the closing section of the fugue. Hence, the correct classification of this fugue would be a triple fugue on a cantus firmus. The ‘fourth theme’ functions, in fact, as a countersubject. In this sense this fugue is similar to Contrapunctus 9, which is a simple fugue over cantus firmus (although there the cantus firmus is the main theme).

5 In this announcement Emanuel explains in detail the usefulness of presenting the fugues in a score format and specifies that The Art of Fugue is printed in this layout.

6 The following generation of Bach scholars marked both these fugues with serial numbers.

7 It was precisely this peculiarity (a triple fugue) that he indicated in all the advertisements, but even this careful definition, which initially appeared to him as irrefutable, proved eventually to be wrong.

8 In his announcement, Emanuel offered an expanded description of The Art of Fugue’s characteristics. Its content proves that he was aware and had an excellent understanding of the details and technical peculiarities of the cycle’s collection of compositions. His only mistake concerning the structure of the cycle could owe itself to two issues. First, when preparing the first publication of The Art of Fugue, he surely did not know that Bach had ‘einen andern Grund Plan’, while he might have been impressed by information concerning the work’s Second Version that Johann Sebastian might have shared with him during his visit to Potsdam, in May 1747. Second, the musical materials of The Art of Fugue, as received by Emanuel, did not easily render the final version of the composition; in fact, it was rather indistinguishable. He must have realised that the previous version had been changed, but he was also aware of his lack of knowledge about it. In such a situation, the optimal decision was to follow the order in which the music was folded and stacked, interpreting it as a direction indicated by his father.

9 It can, in fact, be presented as the Third Version of The Art of Fugue, with one exception: the fugue for two claviers should replace the Contrap: a 4.

10 Their order is kept in Emanuel’s announcement of the subscription.