The title of the fifth piece in the Original Edition looks rather strange, ending with an ‘r’ and thus spelled ‘contrapunctur’ rather than ‘contrapunctus’. This odd ending has always unanimously been interpreted as a simple misprint, and therefore corrected in practically all the work’s editions. Some publishers mark it as an engraver’s error while others correct it without any additional comment, regarding it as an obvious typo. We believe that this peculiarity calls for a deeper inquiry.

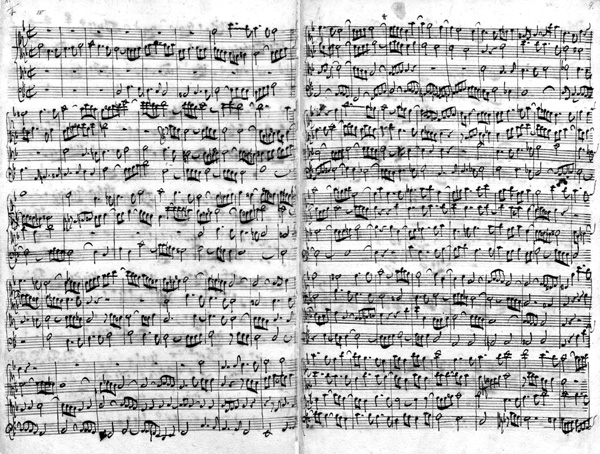

Fugue IV in the Autograph

The Autograph has a particularity quite typical of Bach’s manuscripts. While looking at the pages of fugue IV, which became Contrapunctur 5 in the Original Edition,1 a certain puzzling visual effect is created, similar to that of an ambigram. The two pages of the spread are rastered practically without margins in the middle part, so that the staves almost seem to continue from page to page without interruption. Thus, one way of looking at it allows the perception of a large format in landscape set up, made up of the entire spread, while another reading sees the spread as made up of two separate pages, each in portrait set up (Figure 16.1).

There are grounds to suspect that Bach himself, too, might have perceived such spreads as one landscape page. For example, the score of the Cantata BWV 75 (Die Elenden sollen essen) suggests such a view. Here, too, the raster reaches the middle of the spread, not leaving any margins, so that several staves of both pages seem synchronised, continuing from one page to the other. Here, too, the spread can be perceived either as one landscape page or as two portrait pages. In this case, Bach chose the first option. Clearly, this perception was an afterthought, since the spread was not planned ahead for such a layout: the staves are badly synchronised, worse even than in the autograph. A similar situation can be seen in the autograph of the Mass in B minor, in the movements Patrem omnipotentem (pp. 104–5), Et resurrexit (pp. 116–21), Et ascendit (pp. 121–31) and Et expecto (pp. 140–9). Remarkably, in all these cases Bach does not write clefs or key signatures on the right page of the spread, perceiving the score as one large landscape layout.

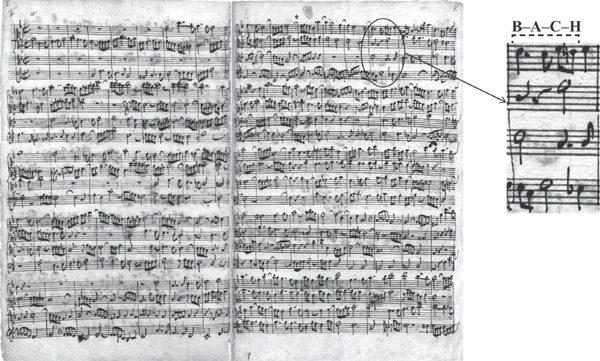

Is there a connection between these ‘ambigrammatic’ layouts and the composer’s fondness of paragrammatic puzzles? Possibly. Bach represented his name by two numerical symbols—14, which was the sum of the numerical values of his name’s letters, and 41, the numerical value of ‘J.S. Bach’. It just so happens that when the autograph of fugue IV is read as if the score is written in landscape layout, following the two top systems of the spread’s two pages as if they were one consecutive system, its 14th bar is, in fact, bar 41 of the fugue, read conventionally (Figure 16.2). Thus, the horizontal and vertical coordinates of this score, carrying the indicators 14 and 41, intersect at one point represented by one and the same bar.2 Could this be a coincidence?

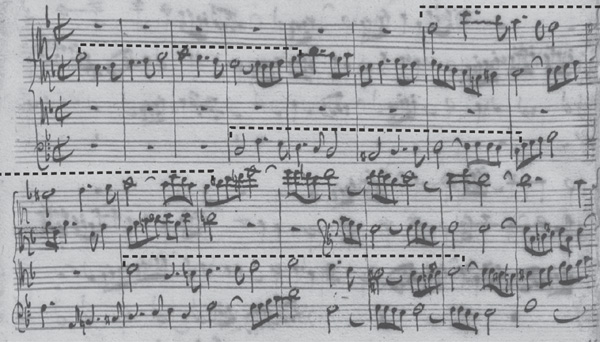

This fugue is special, because the main theme of the collection appears here for the first time in a melodic version with additional passing notes that fill up the gaps between the original half notes, which are now dotted quarter notes. This variant of the theme consists of 14 notes, thus keeping with the symbolic number (Figure 16.3). Moreover, bar 14/41 includes 14 notes, too. Further, the top staff of this bar spells the name B-A-C-H.3 Further yet, framed by bar lines, the inscription spells ‘B-A-C-H C’, marking Bach’s name and his professional position (Bach, C[antor]).

The way in which Bach’s name is displayed in this fugue follows the symbolic principle of multiplicatio:4

• The number of notes in the fugue’s theme is 14.

• The bar number, when the Autograph score is read across the spread, is 14.

• The bar number, when the Autograph score is read in the traditional way, is 41.

• The number of notes in bar 14/41 is 14.

• The letter names of the first notes in the top part of bar 14/41 spell B-A-C-H (the numerical value of which is 14).

While each one of these phenomena could, perhaps, be regarded as coincidental, it does seem in this case there are simply too many signs, accumulated on one spot, to be considered as created by chance.

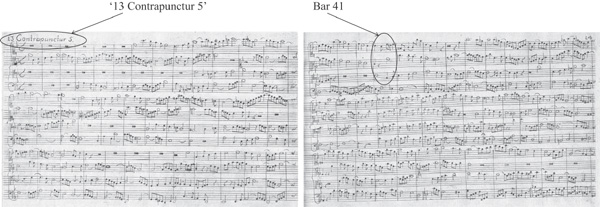

Contrapunctur 5 in the Original Edition

The same piece in the Original Edition of The Art of Fugue acquired a new title and also a different look (Figure 16.4).

The difference in layout is the most noticeable. While the Autograph’s layout is portrait, the Original Edition’s is landscape. Also, unlike in the Autograph, the margins of the Original Edition pages are noticeable (20 mm) and the staves of the spread’s two sides do not coincide, thus preventing the perception of the staves as continuous throughout the page spread. The number of bars on the top staff is 13, obliterating the equivalence of bars 14 and 41. The multiplicatio signs of Bach’s name are now valid only inside bar 41: the number of the bar (14 in retrograde), 14 notes in the bar and the B-A-C-H (C) motif.

However, the landscape layout may have provided Bach with other venues to create signifiers that point at his own name. He did that by combining existing numbers in the layout and numerical values of letters and by introducing an intentional lapsus linguare, a standard mark for the existence of hidden information.5 It was Bach who prepared the engraver copy of this page. Given the slow handwriting and careful alignment of the title, regarding the ‘r’ at the end of the word as a typo is rather unconvincing; even if it were so, the composer would have corrected it at the proofreading stage, just as he did in the case of the Canon in Augmentation.6 The word ‘contrapunctur’, thus, is clearly written intentionally just so.

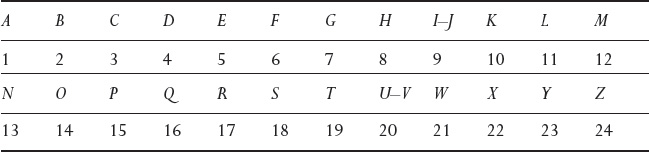

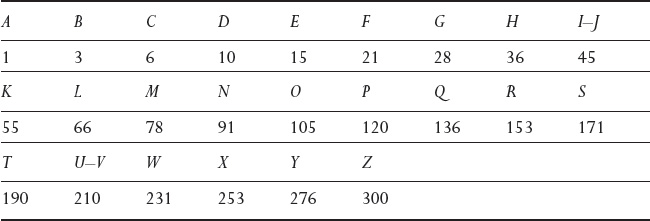

There could be ways to read this allegedly misspelled title, taking into account the intentionality behind it, for example—in yet another ‘numbers and letters’ game.7 It is possible that Bach consulted two methods of numerical equivalents of the Latin alphabet: the ‘natural’ and the ‘trigonal’ systems (Tables 16.1 and 16.2).8

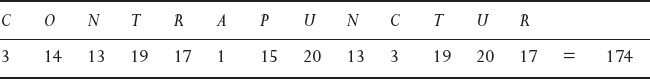

The title of this contrapunctus renders significant information when read in any of these systems. According to the ‘natural’ numerological system, the numerical value of the word ‘contrapunctur’ is 174 (Table 16.3).

The word ‘contrapunctur’, composed of 13 letters, is completely and accurately aligned with the page number—13 and with the serial number of the piece—5 (see Figure 16.4). The first stave of the piece comprises 13 bars, pointing at a possible multiplicatio of the number 13. This is telling, since 13 could be interpreted as a ‘14 minus one’ just as the letter ‘r’ could be interpreted as ‘s minus one’. Further, the number 13 can be also interpreted as two digits, 1 and 3. These readings, combined, may render the following suprising result, which would be possible only with the letter ‘r’ at the end of the title word (Table 16.4).

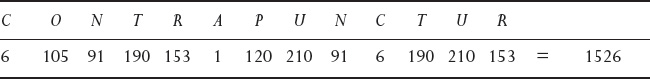

Further, the word ‘contrapunctur’ can be read using another system, the ‘trigonal’. According to that system, the numerical value of the word ‘contrapunctur’ is 1526. Beyond the fact that this number can be divided by 14, the sum of its digits (1 + 5 + 2 + 6) renders 14, too (Table 16.5).

In any of the above readings of the title according to different numerological systems, a meaningful result could be achieved only once the last letter of ‘contrapunctus’ is replaced by the one that is ‘one less’, just like the 13 bars in the first stave are ‘one less’ than the number of bars leading to the significant bar in the Autograph, number 14/41. Regardless of layout, Bach found ways to signify his name through his music composition and notation.

Notes

1 Fugue iv from the Autograph was replaced by the new Contrapunctus 4 that was composed for the Third Version (see Chapter 10), and therefore was ‘pushed forward’ to become the fifth piece in the cycle: Contrapunctur 5.

2 Olga Kurtch, ‘Ot pomet kopiistov’, p. 82.

3 Ibid. Bach marked the same ‘monogram’ in the closing section of the Canon in Augmentation from the Canonic Variations BWV 769a, bars 39–40 (four bars before the end, middle staff, bass clef).

4 The principle of multiplicatio, a basic technique in symbolisation systems, is expressed by a simultaneous—or frequent—appearance of signs, all pointing at one intended signified. For example, a grouping of a sharpened note, a musical motif of a cross (such as, coincidentally, is the name BACH) and the numerical symbol of four, would point by multiplication at one signified: the Cross.

5 Lapsus linguare is an intentional error inserted into an otherwise correct context. Such an error draws attention to itself and to its location within a given text; its appearance in unlikely instances, such as an engraved stone, a title or a printed book cover discloses its intentionality.

6 The Canon in Augmentation is discussed in Chapter 17.

7 This and the following revelations belong to the editor, Esti Sheinberg, whom I deeply thank for strengthening my hypothesis and valuable contribution in general.

8 In the natural system, each letter is assigned a number in consecutive order, that is, a = 1 to z = 24 (the letters ‘I’ and ‘J’ are considered as one letter and thus both equivalent to one number, and so are the letters ‘U’ and ‘V’. In the trigonal system, the advance in value is applied to the differences between the numbers assigned to letters, that is: a = 1; b = 3(= 1 + 2); c = 6(= 3 + 3); d = 10(= 6 + 4); e = 15(= 10 + 5), and so on.