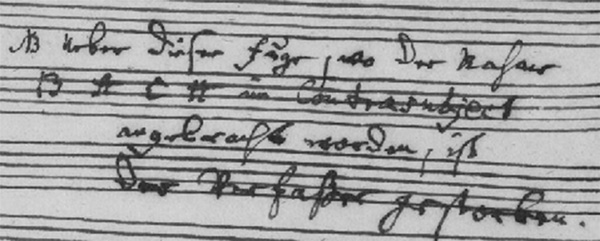

Figure 19.1 P 200/1–3: C.P.E. Bach’s inscription on the last page.

Philipp Emanuel’s inscription on the last page of the autograph of the ‘unfinished’ fugue is familiar to all Bach scholars (Figure 19.1; see also Figure 18.4):

It reads: ‘Ueber dieser Fuge, wo der Nahme BACH im Contrasubject angebracht worden, ist der Verfaßer gestorben’.1

This text puzzles music lovers and, perhaps even more so, professional musicians. In view of the known details about Bach’s inability to compose music in the last months of his life, a certain metaphorical quality of this inscription is apparent, thus leading to a simple acceptance of its existence, without looking for any actual relation to historical facts.

Indeed, the situation described in the inscription is absolutely unrealistic, because between March 31 (the day of Bach’s eye surgery) and July 28 (the day of his death) of 1750, a period that encompasses almost four months, Bach was completely blind and could neither read nor write. Thus, he could not die while working on this fugue. Realising the discrepancy between this inscription and the facts of the composer’s biography, scholars keep trying to understand its real meaning. Consequently, translations such as ‘while working on this fugue…’.2 (presenting the work on the fugue as a process, thus indefinitely stretching the period of time), although similar to the German ‘ueber dieser Fuge’, still sound slightly softer. Such attempts, however, do not really solve the puzzle. There are quite a few other, non-literal interpretations of the text, but none convincingly explain its meaning.

Assuming that Philipp Emanuel was completely aware of the content of his inscription, we propose to interpret the text literally. Clearly, the autograph of the ‘unfinished’ fugue, traditionally dated between August 1748 and October 1749, is the focal point of our inquiry.3 The date was established by Yoshitake Kobayashi, who based his assessment on the peculiarities of Bach’s handwriting at that particular period and on the particular traits of the paper on which the fugue is written. As we remember, however, in another part of his study, Kobayashi stated: ‘Spätestens ab Ende Oktober 1749, als Bach eine Quittung im Zusammenhang mit dem Nathanischen Legat von seinem Sohn Johann Christian schreiben ließ [Dok. I, Nr. 143], leistete er, vermutlich bedingt durch die Behinderung des Sehvermögens, keine Schreibarbeit mehr’.4 It means that the discussed period could be even longer than six months. And if Kobayashi’s dating is correct, then from the moment that ‘the name BACH as a countersubject’ was introduced into the ‘unfinished’ fugue, until the moment in which ‘the author died’, elapsed no less than 10 months and maybe even as long as two years. Philipp Emanuel’s inscription, however, clearly states that both events occurred at the very same moment. Since such an occurrence could not have taken place in reality, Emanuel’s statement is clearly false. Was it an unconscious oversight, or was Emanuel himself misinformed?

If the latter, it would mean that the son was completely clueless about the state of his father’s health during the last years of his life: the deterioration of his eyesight, the surgery and his inability to write. Nevertheless, in the obituary, first written in 1751, Emanuel describes the circumstances of these events in detail. This means that he wrote the inscription on the fugue’s last page while being aware of the factual circumstances around his father’s death, which would make his Nota Bene even more perplexing. Most baffling of all, however, is the assertion, based on Emanuel’s handwriting, that his inscription was written sometime in the 1780s, that is, more than a quarter of a century after Johann Sebastian Bach’s death.

Had the inscription been written soon after his father’s death, it might have been judged as a natural surge of emotional outpouring; a gap of 30 years, though, is strange and requires a more exacting explanation of special, perhaps more complex, contextual circumstances. In 1768, 18 years after his father’s death, Emanuel’s life changed dramatically. In that year he moved from Berlin to Hamburg, after accepting the position of the City’s Music Director and the Kantor in the Johanneum academy.5 Carl Philipp Emanuel found himself in an absolutely new situation. Instead of the royal capital he now resided in a free Hanseatic city, and instead of abiding by Berlin’s pedantic royal court etiquette rules, he enjoyed a more relaxed atmosphere of camaraderie among equals. The instrumental music of the Prussian court was replaced by church music, mostly vocal and choral (although composition of clavier music continued). His circle of friends was quite similar to that of Berlin: mostly artists, sculptors, poets, writers, philosophers and clerics, although there were not so many musicians. The social and financial standings of these creative personalities in the Hanseatic Hamburg, however, were unlike those of the imperial capital. Even a pastor in Hamburg carried other parish callings than a pastor in Berlin and also enjoyed a different social status.

Like his father’s house in Leipzig, Emanuel’s Hamburg home was a hub for artists and thinkers. The atmosphere was created not just by the visitors’ personalities, but also by the ideas that stirred the European society during the last four decades of the eighteenth century, the dominant opinions, typical for educated society, and the popular topics and themes for discussion. Among Emanuel’s circle of friends were the poets and literati Friedrich Gottlieb Klopstock, Johann Wilhelm Ludwig Gleim, Johann Heinrich Voss, Heinrich Wilhelm von Gerstenberg, Heinrich Christian Boie, Gotthold Ephraim Lessing and Christoph Daniel Ebeling;6 the scientist and historian Johann Albert Heinrich Reimarus; the pastor Christoph Christian Sturm and the painter Andreas Stöttrup. Most of these belonged to the Sturm und Drang literary movement that rebelled against the French neo-classical style of the enlightenment aristocracy.7

Fed up with the strenuous and poorly paid service at the court of Frederick II, Philipp Emanuel welcomed the long awaited opportunity to start a new life elsewhere. The Sturm und Drang movement agreed with his own worldview; his compositions included quite a few in genres that were popular among the Sturm und Drang artists whose texts he set to music. He composed spiritual songs (‘geistliche Gesänge’) and songs in popular styles, spiritual odes and a melodeclamation.8

The aesthetic ideals and values enhanced by the Sturm und Drang artists—intuition, subjective views and insight—differed significantly from the enlightenment’s professed rational clarity and balance and took precedence over them. Inexplicable feelings of transcendental entities were perceived as deeper and more meaningful than down to earth reasoning and rational inquiries. The Sturm und Drang art world was imbued with creatures of fantasy taken from ancient myths, German fairy tales and the romantic imagination of poets, playwrights and artists. Night, with its typical attributes, became the favourite time for the narrative: dreams, moonlight, nightingale song, mysterious rustlings and appearances of forest and pond spirits. Favourite topics were death as an unavoidable closure of mystery tales, bloody thrillers involving murder of family members but also stories about life-saving bloodline ties.

The magic power attributed to the name of a person (or a spirit) and its ritual inscription or utterance played a particular role in this cultural milieu. In this regard, Carls Name, a poem by Christian Friedrich Daniel Schubart, of which an excerpt is presented here, is telling:

Ich muß sagen—laut muß ich sagen

Was ihr verschweigt.

CARLS Name flammte heut

Mit Sternengold geschrieben

Am Olymp—Der Name CARLS!!—

Hah! mit welcher Wonne sprech ich ihn aus,

Deinen Namen, CARL!!—

(Pause.)

Zwar wird schon dein Name

An beeden Polen genennt:—

Catharinas weltenstürzender Name

Schlingt sich um ihn!—

Josephs Name—das Erstaunen der Völker—

Schlingt sich um ihn!—

Wodan Friedrichs Name—des Einzigen!

Des Unerreichten!!—

Schlingt sich um ihn!9

In the course of this short excerpt of 15 lines, the word Name [Name] appears seven (!) times, clearly showing that a name is a key concept for the poet. All the proper names are emphasised by expanded spacing, and the name Carl is spelled entirely in capital letters. A Name is endowed with qualities such as blazing [flammte], world overthrowing [weltensturzender], uttered with rapture [mit welcher Wonne sprech ich ihn aus] and inscribed in stars’ gold [mit Sternengold geschrieben]. Not just the inscription but also the pronunciation of the Name is a required action of the poet: ‘I have to say and I should say loud … Carl’s name is blazing today’ [Ich muß sagen—laut muß ich sagen … Carls Name flammte heut…]. Finally, with regard to perception of Name: it is hard to find such an abundance of proper names in any poetic style except for the Sturm und Drang—where names appear even in the titles of poems.

Throughout the second half of the eighteenth century there was a significant increase of interest in ancient Greek literature. This affected the kind of motifs that appeared in Sturm und Drang topics, many of which were focused on family relations. Against the background of horror scenes replete with of parricides, matricides and infanticides, the close relationship between father and son looked particularly gratifying. A typical example of this type is the legend in verse, Das wunderthätige Crucifix [The Miraculous Crucifix], by C.F.D. Schubart, where a deceased father protects his living son, who seeks his father’s guidance. The motive of mutual self-sacrifice is clearly seen. In our context it is significant to note that the names of the spouses, pious and loyal to each other, are Sebastian and Anna. It may also be significant to note that the main focus of the poem quoted above is on Carl.

The period’s imaginative world of poetic reference was greatly influenced by the renewed interest in classical culture in general, inspired by ongoing excavations in Herculaneum and Pompeii. Johann Joachim Winckelmann, the leading scholar of antiquity and a friend of Emanuel’s, introduced the results of these studies to the European educated society. Representatives of the Sturm und Drang embraced the newly found literary and poetic treasures, contributing significantly to new translations of Greek poetry and drama. Subsequently, both content and poetic forms of this literary corpus were adopted and incorporated into the contemporary fashionable poetic styles.

Stories involving the Sphinx and its riddles gained particular popularity. Death awaited the traveller who answered wrongly the riddles, and death awaited the Sphinx if its riddles were solved. The very name Sphinx posed mystery, and its uttering would lead to the Sphinx’s death. The stories reached beyond the unique Oedipus myth, reincarnating into narratives related to the excavations themselves. For example, the account according to which death overtakes the scholar who, when deciphering an ancient manuscript, utters aloud the newly found magic incantation, or the written name of a deity.

The wave of mysticism that swept through Europe in the eighteenth century was not limited to Greek mythology. A great part of it was inspired by the Masonic movement that was popular at that time, particularly among the educated circles of society. An old friend of Philipp Emanuel was Gotthold Ephraim Lessing, with whom he was acquainted from his Berlin years. His Ernst and Falk: Dialogues for Freemasons, written between 1776 and 1778, discuss the political and ethical issues that concerned members of the Masonic order.10 Many of Emanuel’s acquaintances and friends in both Berlin and Hamburg (including Lessing) were Freemasons. It is hard to assert whether Emanuel was a Freemason himself, but his work does relate to Masonic ideas, states of mind and mystic rituals. His Twelve Masonic Songs were published in 1788 and appear in two anthologies.11

Within this setting, the composition circumstances of The Art of Fugue and the death of his idolised father gained a mystical tinge in Emanuel’s mind: the great composer who, while writing his last opus, inscribes his own name, encoding it into his music, and as soon as this mystical procedure is completed, the pen drops off the artist’s hand, concluding his life’s journey. The picture is of Bach parting this world not as a sick and infirm old man in his deathbed, but—as befits an outstanding person and a great musician—in the moment of his greatest inspiration, the conclusion of his opus magnum. How could one resist posing such a picture for posterity? ‘Ueber dieser Fuge, wo der Nahme BACH im Contrasubject angebracht worden, ist der Verfasser gestorben’—this was a far more appropriate description.

Regardless of the excitement such possibility incurres, the simple way of describing what happened is that the beauty of the pictured idea was favoured over the actual facts. It sometimes happens with creative people.

1 [Over this fugue, where the name BACH is stated in the countersubject, the author died.]

2 NBR, no. 285, p. 260.

3 Kobayashi, ‘Zur Chronologie’, pp. 62 and 70.

4 [At the very latest, occurred by the end of October 1749, when Bach’s receipt concerning the Nathan Bequest (Nathanischen Legat) was written by his son Johann Christian (Doc. 1, No. 143) most likely, due to deterioration of vision, he could no more perform any writing work.] Ibid. p. 25.

5 In this, Philipp Emanuel echoed the life change of his father, who moved from Cöthen to Leipzig, replacing the position of the court Kapellmeister with that of the Leipzig Music Director.

6 Ebeling also translated to German Charles Burney’s The Present State of Music in France and Italy (London, 1771), published as Carl Burney’s der Musik Doctors Tagebuch einer musikalischen Reise durch Frankreich und Italien (Hamburg, 1772) and The Present State of Music in Germany, the Netherlands, and United Provinces London (London, 1773), published as Carl Burney’s der Musik Doctors Tagebuch seiner Musikalischen Reisen (Hamburg, 1773).

7 Sturm und Drang was a literary and artistic movement in Germany during the 1760s–1780s, named after one of Friedrich Maximilian Klinger’s dramatic plays. Several of its representatives belonged to Emanuel’s close circle, while with others he had intensive correspondence.

8 These works were published not only as individual songs but also as collections of vocal works published during the composer’s lifetime and issued in several editions (for example: Herrn Christoph Christian Sturms / Hauptpastors an der Hauptkirche St Petri und Scholarchen in Hamburg / Geistliche Gesänge / mit / Melodien zum Singen bey dem Claviere / vom Herrn Kapellmeister Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach / Musikdirektor in Hamburg (Hamburg, 1780), the cover of the latter publication illustrated by Andreas Stöttrup.

9 ‘CARLS Name / gefeyert von der deutschen Schaubühne zu Stuttgart. / am 4. Nov. 1784’, in Christian Friedrich Daniel Schubart sämtliche Gedichte, vol. 2 (Stuttgart, 1786), pp. 29–30.

10 Gotthold Ephraim Lessing, Ernst und Falk: Gespräche für Freymäurer (1776–1778), in his Theologiekritischen und Ästhetischen Schriften, vol. 5 (München, 1970). Translated to English by Hugh Barr Nisbet in Gotthold Ephraim Lessing, Philosophical and Theological Writings (Cambridge, 2005).

11 Freymauer-Lieder mit ganz neuen Melodien von den Herren Capellmeistern Bach (Copenhagen, 1788); Allgemeines Liederbuch für Freymaurer, vol. III (Copenhagen, 1788).