Epilogue: the origins of agriculture

AROUND 10,000 years ago, people changed from being hunter-gatherers to farmers in many different regions of the world. This transformation took place quite independently in parts of Southwest Asia, Equatorial Africa, the Southeast Asian mainland, Central America and in lowland and highland South America. The onset of farming is frequently invoked as the turning point of prehistory. Without agriculture we would not have had towns, cities and state society. It is these that have so fundamentally changed the contexts in which the minds of individuals develop today from those of our hunter-gatherer ancestors. So how did this change come about? In my Epilogue I will argue that the rise of agriculture was a direct consequence of the type of thinking that evolved with the emergence of cognitive fluidity. More specifically, I will propose that there were four aspects of the change in the nature of the mind which resulted in a reliance on domesticated plants and animals when environmental conditions abruptly altered 10,000 years ago. Before looking, however, at just what these changes in the mind might have been, we need to consider briefly some of the broader issues involved in the origins of agriculture.

The introduction of farming is viewed as one of the great mysteries of our past. Why did it happen? Certainly not because of the crossing of a threshold in accumulated knowledge about plants and animals, enabling people to domesticate them.1 As I have argued in this book, hunter-gatherers – whether Early or Modern Humans – are and were expert natural historians. We can be confident that knowledge about how animals and plants reproduce, and the conditions they need for growth, had been acquired by human minds as soon as a fully developed natural history intelligence had evolved, at least 1.8 million years ago.

The knowledge prehistoric hunter-gatherers possessed about animals is readily apparent from the diversity of species we know they hunted, to judge by the bones found at their settlements. It is only quite recently, however, that archaeologists have been able to document a similar level of exploitation of plant foods by prehistoric hunter-gatherers. Consider, for instance, the 18,000-year-old sites in the Wadi Kubbaniya, which lies to the west of the Nile Valley. The charred plant remains discovered here indicate that a finely ground plant ‘mush’ had been used, probably to wean infants. A diverse array of roots and tubers had been exploited, possibly all the year round, from permanent settlements.2 Similarly, at Tell Abu Hureyra in Syria, occupied by hunter-gatherers between 20,000 and 10,000 years ago, no fewer than 150 species of edible plants have been identified, even though roots, tubers and leafy plants were not preserved.3 At both these locations we see the technology for pounding and grinding plant material – the same as that used by the first farmers (see Figure 34). In summary, these sites demonstrate that the origins of agriculture 10,000 years ago are not to be sought in a sudden breakthrough in technology, or the crossing of a threshold in botanical knowledge.

So why did people take up farming? An element of compulsion must have been involved. Despite what we might intuitively imagine, farming did not automatically liberate our Stone Age ancestors from a hand-to-mouth, catch-as-catch-can existence. Indeed quite the opposite. Living by agriculture comes a very poor second when compared with living by hunting and gathering. The need to look after a field of crops ties down some members of a community to a particular spot, creating problems of sanitation, social tensions and the depletion of resources such as firewood. Hunter-gatherers easily solve these problems by being mobile. As soon as their waste accumulates, or fire wood is depleted, they move on to another campsite. If individuals or families have disagreements, they can move away to different camps. But as soon as crops need regular weeding, and labour has been invested in building storage facilities or irrigation canals which need maintaining, the option to move on is lost. It is no coincidence that the earliest agricultural communities of the Near East show substantially poorer states of health than their hunter-gatherer forebears, as we know from studies of their bones and teeth.4

34 Mortar and pestle for processing plants from site E-78-4, Wadi Kubbaniya, c. 18,000 years old.

People therefore must have had some incentive to switch to farming. Moreover that incentive must have been on a world wide scale 10,000 years ago, if we are to account for the fact that diverse methods of food production started independently in such a relatively short time period around the globe.5 The crops being cultivated varied markedly, from wheat and barley in Southwest Asia, to yams in West Africa, to taro and coco nuts in Southeast Asia.

Conventionally, two explanations are put forward for this near-simultaneous adoption of agriculture. The first is that at around 10,000 years ago population levels had gone beyond those that could be supported on wild food alone. The world had effectively become full up with hunter-gatherers and there were no new lands to colonize. As a result, new methods of subsistence were required to provide more food, even if they were labour intensive and came with an assortment of health and social problems.6

This idea of a global food crisis in prehistory is both implausible and not supported by the evidence. We know from studies of modern hunter-gatherers that they have many means available for controlling their population levels, such as infanticide. Mobility itself constrains the size of population due to the difficulties of carrying more than one child. Furthermore, we know that in some instances at least the health of the last hunter-gatherers in a region where agriculture was adopted appears to have been significantly better than that of the first farmers. This is evident from the study of pathologies on the bones of the last hunter-gatherers and the first farmers. Such evidence shows that the onset of agriculture brought with it a surge of infections, a decline in the overall quality of nutrition and a reduction in the average length of life.7 The rise of farming was certainly not a solution to health and nutritional problems faced by prehistoric populations; in many cases it appears to have caused them. Nevertheless, although a global population crisis is implausible, the possibility remains that production of foodstuffs became necessary to feed relatively high local populations.

A second and partially more convincing explanation for the introduction of farming 10,000 years ago is that the whole world at that time was experiencing dramatic climatic changes associated with the end of the last ice age. There was a period of very rapid global warming – recent research indicating perhaps as much as an astonishing 7°C (over 12°F) in a few decades – that marked the end of the last glacial period.8 This was preceded by a series of fluctuations 15,000–10,000 years ago, switching the globe from periods of warm/wet to cold/dry climate and back again. These climatic fluctuations were truly global affairs. The near-simultaneous adoption of farming in different parts of the world therefore appears to represent local responses, to the local environmental developments, caused by the global climatic changes immediately before and at 10,000 years ago as the last ice age came to an end. As we shall see, this cannot entirely account for the rise of farming, since Early Humans experienced similar climatic fluctuations without abandoning their hunting and gathering way of life. But first let us pause in our argument to consider one particular region, so as to understand better what really happened as farming took hold.

We can see the close relationship between changing methods of food procurement and late ice age climatic instabilities in Southwest Asia, where the origins of agriculture have been studied in most detail. Here we see the first farming communities of domesticated cereals (barley and wheat) and animals (sheep and goat) at sites such as Jericho and Gilgad at around 10,000 years ago. These settlements are found in precisely the area where the wild ancestors of these domesticated cereals had grown and had been exploited by the hunter-gatherers, such as those from Abu Hureyra.

Indeed the stratified sequence of plant remains at Abu Hureyra, as studied by the archaeobotanist Gordon Hillman and briefly referred to above, is very informative about the switch from a hunting and gathering to a farming lifestyle.9 Between 19,000 and 11,000 years ago the environmental conditions in Southwest Asia improved, as the ice sheets of Europe retreated, leading to warmer and moister conditions, particularly during the growing season. This is likely to have been a period during which hunter-gatherer populations increased, since they were able to exploit ever more productive food plants, and gazelle herds moving along predictable routes.10 At Abu Hureyra we find evidence in fact that a wide range of plants was being gathered. Between 11,000 and 10,000 years ago, however, there was a marked return to much drier environmental conditions, even drought.11

This drought had severe consequences for the hunter-gatherers of Abu Hureyra. In successive archaeological layers at the site we see the loss of tree fruits as a source of food – reflecting the loss of trees because of the drought – and then the loss of wild cereals, which were unable to survive the cold dry environments. To compensate we see a marked increase in small seeded legumes, plants which were more drought resistant but which also required careful detoxification to make them edible. At around 10,500 years ago Abu Hureyra was abandoned; when people returned there 500 years later, they came to live as farmers.

The significance of this drought, and possibly earlier climatic fluctuations, for the change in hunter-gatherer lifestyles is seen throughout Southwest Asia. In the region of the Levant, to the south and west of Abu Hureyra, we can see that around 13,000–12,000 years ago hunter-gatherers changed from a mobile to a sedentary lifestyle probably in response to a short, abrupt climatic crisis of increased aridity which resulted in dwindling and less predictable food supplies.12 Although people continued to live by hunting and gathering, the first permanent settlements with architecture and storage facilities were constructed.13 This period of settlement is known as the ‘Natufian’, and lasted until 10,500 years ago when the first true farming settlements appear.

The Natufian culture marked a dramatic break with what went before.14 Some of the new settlements were extensive. That at Mallaha involved digging under ground storage pits and levelling slopes to create terraces for huts. The range of bone tools, art objects, jewellery and ground stone tools expanded markedly. Some of the Natufian flint blades have what is known as a ‘sickle gloss’, which suggests that stands of wild barley were being intensively exploited. But the people living in these settlements still supported themselves by wild resources alone. The critical importance of the Natufian for the origins of agriculture is that it constituted what has been described by the archaeologists Ofer Bar-Yosef and Anna Belfer-Cohen as ‘a point of no return’.15 Once that sedentary lifestyle had been put in place it was inevitable that the level of food production would need to increase, because the constraint on population growth imposed by a mobile lifestyle had been relaxed. Although it remains unclear quite why the sedentary lifestyle was chosen, it seems to have arisen out of decisions made by hunter-gatherers when faced with the short, abrupt climatic fluctuations at the very end of the last ice age.

It is likely that elsewhere in the world hunter-gatherers also reacted to the climatic fluctuations of the late Pleistocene in ways that involved either the direct cultivation of plants, or the adoption of a sedentary lifestyle which eventually committed them to a dependence on domesticated crops. But this cannot be the whole story of the origins of agriculture. As I have stressed at several places in this book, the Early Humans of Act 3 lived through successive ice ages. They too had been faced with marked climatic fluctuations, and experienced a dwindling of plant foods and the need for change in their hunting and gathering practices. But at no time did they develop sedentary lifestyles or begin to cultivate crops or domesticate animals. So why did so many groups of Modern Humans, when faced with similar environmental changes, independently develop an agricultural way of life?

The answer lies in the differences between the Early Human and the Modern Human mind. If my proposals for the evolution of the mind are correct, then Early Humans simply could not have entertained the idea of domesticating plants and animals, even when suffering severe economic stress, hypothetically surrounded by wild barley and wheat, and magically provided with pestles, mortars and grinding stones. The origins of agriculture lie as much in the new way in which the natural world was thought about by the modern mind, as in the particular sequence of environmental and economic developments at the end of the Pleistocene. There are four aspects of the change in the nature of the mind which were critical to the origins of agriculture.

1. The ability to develop tools which could be used intensively to harvest and process plant resources. This arose from an integration of technical and natural history intelligence. Little more needs to be said about this ability, for such technological developments were discussed in Chapter 9. We see the appropriate technology for the cultivation of plants in use at Wadi Kubbaniya and Abu Hureyra by 20,000 years ago.

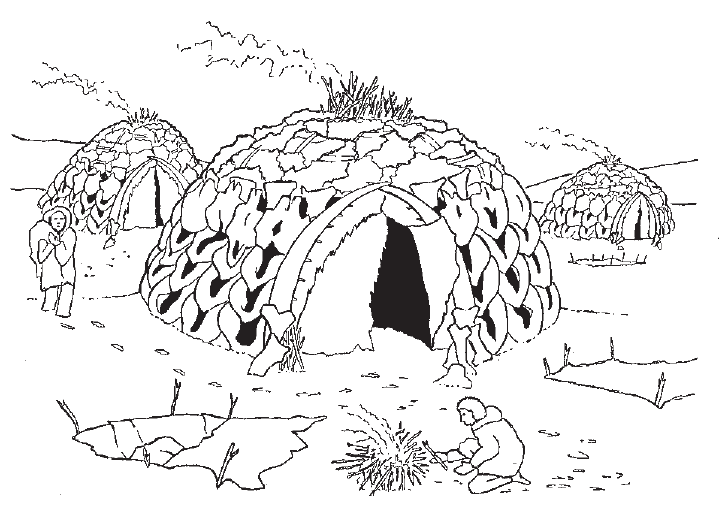

2. The propensity to use animals and plants as the medium for acquiring social prestige and power. This arose from an integration of social and natural history intelligence. We can see several examples of this in the behaviour of hunter-gatherers after 40,000 years ago in Europe. Consider, for instance, the way in which the storage of meat and bone was used on the Central Russian Plain between 20,000 and 12,000 years ago, a period during which people constructed dwellings from mammoth bones and tusks (see Figure 35). The stored resources came from animals such as bison, reindeer and horse which were hunted on the tundra-like environments of the last ice age. Olga Soffer has described how during the course of this period access to stored resources came increasingly under the control of particular dwellings.16 Individuals appear to have been using stored meat, bone and ivory not just as a source of raw material and food, but as a source of power.

We can see something similar in the hunter-gatherer communities of southern Scandinavia between 7,500 and 5,000 years ago. These people exploited game such as red deer, wild pig and roe deer in thick mixed-oak forests. By looking at the frequencies with which different species were hunted, and by studying the hunting patterns with computer simulation, we can deduce that they were focussing on red deer – even though this often left the hunters returning to their settlements empty-handed, because red deer were much scarcer and more difficult to kill than, say, the smaller and more abundant roe deer.17 Why were they doing this? It is most likely that the preference for red deer arose from the larger size of the animal. More meat could be given away from a red deer carcass, providing greater social prestige and power. Day-to-day fluctuations in meat from hunting could be coped with by exploiting the rich plant, coastal and aquatic foods in the region, especially by using facilities such as fish traps that could be left unattended, some of which have been found almost perfectly preserved in waterlogged conditions. This idea is confirmed when we look at the burials of the hunter-gatherers. Antlers of red deer and necklaces made from their teeth are prominent in the grave goods.18

35 Mammoth-bone dwellings and storage pits on the Central Russian Plain, c. 12,000 years ago.

This use of animals, and no doubt plants, as the means for gaining social control and power within a society was absent from Early Humans. Their thought about social interaction and the natural world was undertaken within isolated cognitive domains and could not be brought together in the required fashion. This difference is critical to the origins of agriculture. While sedentary farming may represent a poorer quality of life for a community as a whole, when compared with a mobile hunting-gathering lifestyle, it provides particular individuals with opportunities to secure social control and power. And consequently, if we follow the proper Darwinian line of focussing on individuals rather than groups, we can indeed see agriculture as just another strategy whereby some individuals gain and maintain power.19

The archaeologist Brian Hayden favours this explanation for the origins of agriculture. In a 1990 article he argued that ‘the advent of competition between individuals using food resources to wage their competitive battles provides the motives and the means for the development of food production’.20 He used examples from various modern hunter-gatherer societies to show that when technological and environmental conditions allow it, individuals try to maximize their power and influence by accumulating desirable foods and goods, and by claiming ownership of land and resources.

When Hayden looked at the Natufian culture, he felt that the evidence for the long-distance trade of prestige items, and the abundance of jewellery, stone figurines and architecture were all clear signs of social inequality, reflecting the emergence of powerful individuals. Once that social structure had arisen, there was a need for the powerful individuals continually to introduce new types of prestige items and to generate economic surpluses to maintain their power base. Food production is an inevitable consequence – as long as there are suitable plants and animals in the environment for domestication. As Hayden notes, many of the first domesticates appear to be prestige items – such as dogs, gourds, chilli peppers and avocados – rather than resources which could feed a population grown too large to be supported by wild resources alone.

3. The propensity to develop ‘social relationships’ with plants and animals, structurally similar to those developed with people. This is a further consequence of an integration of social and natural history intelligence. In order to domesticate animals and plants, it was necessary for prehistoric minds to be able to think of them as beings with whom ‘social’ relationships could be established. As I have argued, Early Humans with their Swiss-army-knife mentality could not have entertained such ideas.

We can see evidence for the emergence of ‘social relationships’ between people and wild animals and plants among the prehistoric hunter-gatherers of Europe. For instance, in the Upper Palaeolithic cave sites of Trois-Frères and Isturitz in France reindeer bones have been found with fractures and injuries that would have seriously inhibited the animals’ ability to move and feed. Nevertheless these reindeer survived for sufficient time to allow the fractures to start healing and it has been proposed that they were cared for by humans21 – in much the same way as the crippled Neanderthal from Shanidar Cave referred to in Chapter 7 had been looked after.

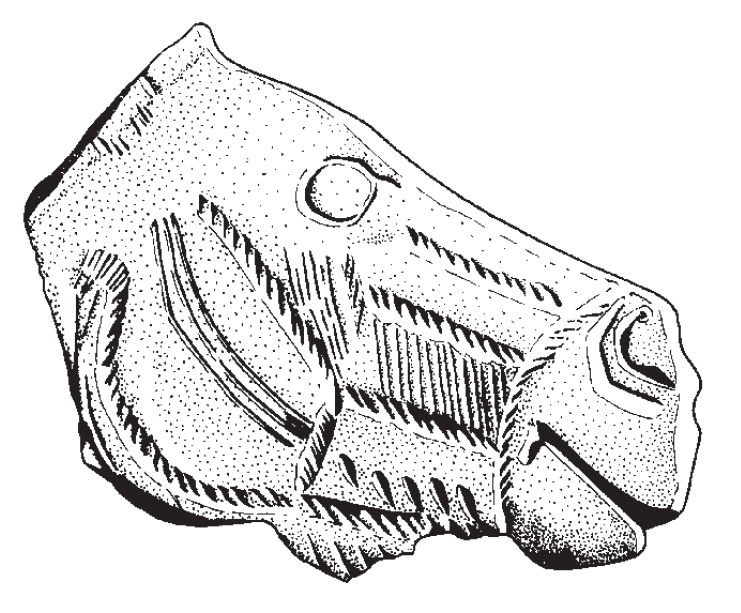

There are also a few intriguing examples of horse depictions from Palaeolithic art which seem to show the animals wearing bridles – although it is difficult to tell, and the marks may simply identify changes in colour or bone structure (see Figure 36).22 We know for sure, however, that dogs were domesticated shortly after the end of the ice age. Indeed in the hunter-gatherer cemeteries of southern Scandinavia dating to around 7,000 years ago, we find dogs which had received burial ritual and grave goods identical to those of humans. There is also a grave from the Natufian settlement of Mallaha which has a joint burial of a boy with a dog.23

The ability to enter into social relationships with animals and plants is indeed critical to the origins of agriculture. The psychologist Nicholas Humphrey drew attention to the fact that the relationships people have with plants bear close structural similarities to those with other people. Let me quote him:

the care which a gardener gives to his plants (watering, fertilising, hoeing, pruning etc.) is attuned to the plants’ emerging properties…. True, plants will not respond to ordinary social pressures (though men do talk to them), but the way in which they give to and receive from a gardener bears, I suggest, a close structural similarity to a simple social relationship. If … [we] … can speak of ‘conversation’ between a mother and her two month old baby, so too might we speak of a conversation between a gardener and his roses or a farmer and his corn.

36 Horse’s head from St-Michael d’Arudy, Pyrénées-Atlantiques, France. Length 4.5 cm.

As Humphrey goes on to note, ‘many of mankind’s most prized technological discoveries, from agriculture to chemistry, may have had their origin … in the fortunate misapplication of social intelligence.’24

4. The propensity to manipulate plant and animals, arising from an integration of technical and natural history intelligence. We can think of this as the misapplication of technical intelligence, for just as Modern Humans appear to have begun treating animals and plants as if they were social beings, so too did they treat them as artifacts to be manipulated. Perhaps the best example of this is from the hunter-gatherers of Europe, who lived in the mixed-oak forests after the end of the last ice age. They were deliberately burning parts of the forest.25 This is a form of environmental management/manipulation that acts to encourage new plant growth and attract game. It is a practice that has been well documented among the Aboriginal communities of Australia who under took it perfectly aware that by doing so they were removing exhausted plant growth and returning nutrients to the soil to facilitate new growth. Indeed, by looking at the accounts of how the indigenous Australians exploited their environments we find evidence for many practices which are neither simple hunting and gathering, nor farming. For instance, in south western Australia, when yams were intensively collected, a piece of the root was always left in the ground to ensure future supplies.26

Modern Humans living as hunter-gatherers during prehistory probably developed relationships with plants and animals of a similar nature to those observed among recent hunter-gatherers. They are unlikely to have been simple predators, but engaged in the manipulation and management of their environments – although this fell short of domesticating resources. This was indeed recognized a quarter of a century ago by the Cambridge archaeologist Eric Higgs.27 He encouraged a generation of research students to challenge the simple dualism between hunting-gathering and farming. We now know that these are just two poles on a continuum of relationships developed by prehistoric hunter-gatherers. But these relationships were only developed after 40,000 years ago, when ideas about animals and plants as beings to be manipulated at will or with whom ‘social relationships’ could be developed arose.

The four abilities and propensities I have outlined fundamentally altered the nature of human interaction with animals and plants. When people were faced with immense environmental changes at the end of the last ice age it was the cognitively fluid mind that made it possible for them to find a solution: the development of an agricultural lifestyle. In any one region there was a unique historical pathway to agriculture, in which some of these mental abilities and propensities may have been more important than others. But while the seeds for agriculture may have been first planted 10,000 years ago, they were first laid in the mind at the time of the Middle/Upper Palaeolithic transition. It is this key epoch and not the period of the birth of agriculture that lies at the root of the modern world. I have therefore treated the origins of agriculture as no more than an epilogue to my book. Nevertheless agriculture fundamentally changed the developmental contexts for young minds: for the vast majority of people alive today, the world of hunting and gathering, with its specialized cognitive domains of technical and natural history intelligence, have been left behind as no more than prehistory.

I have tried to demonstrate in this book the value of reconstructing that prehistory. For our minds today are as much a product of our evolutionary history as they are of the contexts in which we as individuals develop. Those stone tools, broken bones and carved figurines that archaeologists meticulously excavate and describe can tell us about the prehistory of the mind. And so, if you wish to know about the mind, do not ask only psychologists and philosophers: make sure you also ask an archaeologist.