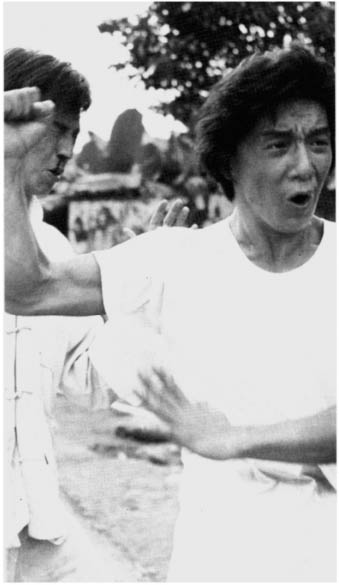

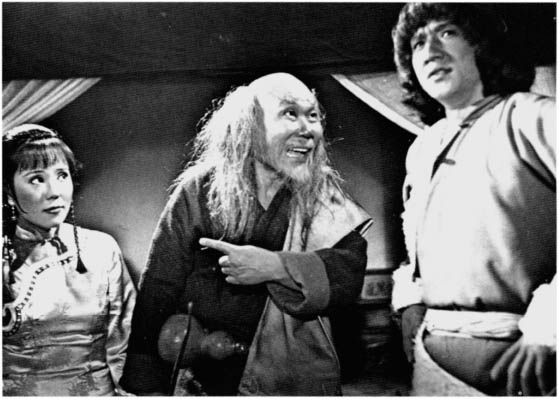

Half a Loaf of Kung Fu (1978). (Colin Geddes/Asian Eye)

“Bruce Lee number one. John Wayne number two. Jackie Chan number three. That’s the way I would like to be remembered in the history books.”

—Jackie Chan

Not since the death of Bruce Lee in 1973 has the world claimed a cinematic icon greater than Jackie Chan. While Hollywood creates lethargic, pretentious productions starring multimillion-dollar actors, Chan’s vision has remained pure and simple despite temptation. That vision is forged from the comic inventiveness of the silent era, the traditionalism of the East, and the basic semantics of the common man. Chan has escaped the unpopular label of “Bruce Lee imitator” to become an international phenomenon claiming legions of fans around the globe and transcending cultural boundaries. Chan has kept the entire Hong Kong film industry afloat for two decades, sustaining the interest of foreign investors and distributors despite the decreasing quality of Hong Kong films in general. And yet, with more than forty starring roles under his belt, Jackie Chan’s ultimate love is unchanged: to bring “something different” to the screen each time.

In the end, audiences are treated to an awe-inspiring experience much like watching acrobats on the trapeze, though Chan’s inventive action sequences go far beyond any circus act. He doesn’t require the new technologies of Hollywood special effects or even a well-written script. He is the special effect. Chan has created his own genre, one that enables him to play his underdog hero in every film without letting his audience grow tired of a routine. He shapes his inventions by exerting firm control over every facet of film production, building an impressive career as a stuntman, actor, director, producer, choreographer, writer, and singer in the process. Now, having gained the recognition of American audiences, Chan has transcended cultural (and cultish) pigeon-holing: he is no longer the “Clown Prince of Kung Fu.”

Audiences haven’t seen a screen character like Jackie Chan for more than sixty years. With Charlie Chaplin’s accented facial mannerisms, Buster Keaton’s unpredictable physical feats, and Fred Astaire’s rhythm in gliding across the screen, Chan can be enjoyed universally by all who miss the innocent romance with the camera that has been lost in present-day Hollywood stylizations. Let this book serve as well-deserved fanfare of his storybook rise to fame, exploring the components of his charmingly guileless onscreen presence, the films that made him a success, and his breathtaking filmmaking techniques—especially his world-renowned action sequences.

Jackie Chan was born in Hong Kong on April 7, 1954, as Jacky Chan Kong-sang to Charles and Lee Lee Chan, a cook and a cleaning lady, respectively. Born to poverty-stricken parents, Chan was almost sold for a mere $26 to the British doctor who delivered him. Charles Chan, skilled in the martial arts, began pushing Jacky at an early age into athletics. The young Chan would wake up at six in the morning to commence training: a quick jog, then a workout on wooden shelves and sandbags made up by his father. The young Chan was more interested in playing games than studying, so his father had to find an outlet for his son’s energy. With little money to care for Jacky and aspirations to work for the American embassy in Australia (Charles was the personal cook for the Australian consulate), Charles eventually took Jacky to Zhonggou Xiju Xueyan (Chinese Opera Research Institute) in Hong Kong at the age of seven and a half. The institute was located in Tsimshatsui, a thriving district in Kowloon where Chan’s offices stand today. With only 1,900 square feet to work with, the institute was unusually small for a drama academy of this type. Still, the school’s headmaster, Yu Jim-yuen, more than made up for the lack of size. There were several instructors, but Yu was the driving force behind the success of its students. The young Chan signed a seven-year apprenticeship contract here in 1961, although he would follow Yu for another three years.

Chinese Opera dates back many centuries to the Southern and Northern dynasties, when ancient songs and dances were offered to the gods for good fortune. As it evolved, the operas examined human mores, drawing from Chinese history and folklore and using music to drive the action. The operas are a pageant of color, song, and action. Although every region had its own style of opera, Peking Opera became the paradigm, bringing together, in fact, other regional operas. Now, the terms Peking Opera and Chinese Opera are used interchangeably.

To be a Chinese Opera performer demanded abilities in dancing, singing, acrobatics, martial arts, and stage makeup. As author Tyan Shuh-lin explains in How To Appreciate Chinese Opera, “The movements of Chinese Opera not only call for grace in posing, but also for meticulous coordination with the pace set by the beat of the drums and agreement with the nature of the music.”

To meet the demand for performers, Chinese Opera schools sprang up everywhere across China. And because the performers had to have incredible physical abilities, children were recruited who could undergo intense training. Essentially traveling circuses, Peking Opera schools served as pseudo-foster homes for many children whose parents couldn’t afford to keep them. Out of respect for the headmaster, the students would assume names as part of his family, so Yu Jim-yuen’s name was incorporated into those of his students. Here, Yuen Lau (as Chan was named) would work from 5 a.m. to midnight with the other students, learning every aspect of stage performance, including stage makeup application and acting. Chan was the mischievous one of the group and was more regarded for his singing ability than for his martial arts skills.

At the Chinese Opera Research Institute, the children had to sign waivers giving the teachers full control to use whatever means necessary to (sometimes literally) whip them into shape. The students also signed contracts stating that whatever money they made performing would go to the master and that parents were not allowed to watch their own children learning. The students would be taught many different drills to prepare them for the stage: waist and foot training (an exercise for balance and coordination), circle running, broken-step walk (a term that describes simple stances and movements for martial arts), and types of wrestling. Instead of grades, food would be the reward for completing these tasks, and the master had no problem using his thick whip to exert power. At the end of each night, the students would have to serve their master through a variety of massaging techniques—bringing the master’s strength back, ironically, for tomorrow’s punishment.

A scene from Painted Faces, a film based on the Seven Little Fortune’s experiences in the Chinese Opera Research Institute.

In 1989 a rare collaboration between Golden Harvest and the Shaw Brothers created Painted Faces, a film based on the life and times of Jackie and his fellow Peking Opera school friends. Sammo Hung played the role of Master Yu Jim-yuen, and Yuen Wah choreographed the film. Chan himself is quick to mention that the film is actually only 20% accurate. He likens his experience to that depicted in the popular Chinese film Farewell My Concubine (1993). Sammo Hung was quoted as saying that the exercises performed in Painted Faces were actually the exercises that the real Mr. Yu practiced when he was a student at a similar school. Master Yu did attend the film’s premiere in Hong Kong. “[He] didn’t like it or my performance very much,” recalled Hung recently. “He said that he was portrayed as being too stern when actually he was much, much worse!” Master Yu presently resides in Los Angeles but has Alzheimer’s disease—he didn’t even recognize Chan when he came to visit him.

It was here that Chan, affectionately called “Big Nose,” befriended many students who would eventually grow up with him and become big stars on their own. Sammo Hung Kam-bo (Chu Yuen Lung), Yuen Biao, Yuen Kwai, and Yuen Wah were some of them. With Chan, they formed the Seven Little Fortunes Opera group. The group actually had fourteen members, but only seven would appear on stage at one time. Chan’s father came to visit his son once every two years until his unsuccessful business in Australia kept him from doing so. Chan’s parents would keep in contact with him almost entirely by mail, managing to send him some money each month, but his real family was his teacher and his schoolmates (whom he claimed as his “brothers”).

Performing live gave these youngsters a chance to exercise their skills, but the early sixties brought the deterioration of Peking Opera. Burlesque shows and the cinema were becoming more popular. Chan and his new family had to keep working, so they moved to films. In 1962, one year after his induction into the Peking Opera school, Chan made his film debut in Big and Little Wong Tin Bar, one of several childhood films he called “seven-day films” because they would take only seven days to shoot.

Bruce Lee in Enter the Dragon (1973).

By 1971, Chan (who was seventeen) and his Peking Opera school chums were out of luck. The school closed down, leaving its uneducated students (reading and writing were secondary skills) to fend for themselves. They had vast stage knowledge, but Cantonese opera films were meeting a fate similar to that of the stage productions. Musicals and films with anti-Japanese themes were beginning to decline, as well, so breaking into kung fu films was their only choice. Wu xia pian (Cantonese martial arts) was becoming one of the most important Cantonese film genres at the time. The films were nothing more than longer, less arty versions of Peking Opera, so it was a natural progression for the students to find cinema work as bit players and stuntmen. The popularity of Chinese kung fu films was not unlike America’s fascination with movies about the Old West. While America had Billy the Kid and other legendary gunslingers, Chinese historical figures, such as Hwang Fei-hung, became bigger than life on the screen. Instead of guns and plots dealing with families fighting over land, it was kung fu and martial arts clans fighting over supremacy of styles. Even though the genre was limited in terms of sets and plots, the films could be made in weeks, and scripts could be watered down since the films were mostly fighting.

When the Shaw Brothers film studio released The One-Armed Swordsman in 1968, it was a transitional sign that something was about to change in the realm of the martial arts film genre. As Ric Meyers, author of From Bruce Lee to the Ninjas, explains, “After years of Confucian morality and bloodless, unconvincing, stagy fights, The One-Armed Swordsman showed them a tortured anti-hero who thought nothing of slaughtering his enemies.” The film launched director Chang Cheh as the master of kung fu/swordplay mayhem, but the real significance of this film is how it paved the way for the new screen hero who was about to dominate the industry.

When Bruce Lee leapt off the screen in Fists of Fury (the Hong Kong title is The Big Boss)1 in 1971, he literally destroyed the fancier, stagelike martial arts productions and replaced them with a realism that the genre had been lacking. The difference between Lee and One-Armed Swordsman star Wang Yu was simple: Lee was an unrelenting and unbeatable hero.

Lee personified the heart and soul of why this genre was important, and the unemployed Peking Opera graduates had no problem assimilating. Yuen Wah found the most significant role as Bruce Lee’s stunt double, performing all of the acrobatic needs of Lee’s roles. Yuen can be seen in The Chinese Connection (Fist of Fury) as a Japanese student who mocks Lee as he approaches the gate with its famous inscription “No Chinese or Dogs Allowed.” Jackie Chan appears in a brief shot at the beginning of The Chinese Connection and also worked as a stuntman on the film (he doubled for Mr. Suzuki, who is kicked through the wall during the final fight). Chan was one of many oncomers who attack Lee in Han’s underground headquarters in Enter the Dragon: Chan bear hugs Lee only to have Lee grab him by the hair and snap his neck. Sammo Hung fought Lee at the beginning of Enter the Dragon and even served as second unit director and bit player on Game of Death.

Up until this time in Hong Kong cinema, screen presence was not an essential aspect of an actor’s performance. Films were shot in very short time periods, and actors didn’t have to worry about diction since Chinese dialects other than Cantonese (Hong Kong’s main dialect) were dubbed in. The explanation for this dubbing is complex. Cantonese opera films did display an actor’s vocal potential, since they were shot in synch-sound for Hong Kong audiences only, but for other Chinese films, it was important for actors to be able to speak in impeccable Mandarin—the language of 90% of China’s population—which not all actors could do. As a result, it was necessary to shoot the films silently. Then the film would be dubbed into Cantonese or Mandarin using only native speakers in those languages—actors often didn’t dub their own voices. (A jolly man named Chan Bowing actually made a career out of dubbing the Cantonese voices for Jackie Chan and Sammo Hung.) So synch-sound filmmaking—where sound and action are recorded/filmed at the same time—was abolished. This practice was carried on for nearly three decades, until director Stanley Tong insisted on synch-sound in Police Story III: Super Cop in 1992. Several directors followed suit shortly thereafter, using Cantonese as the central dialect for the films.

As for Bruce Lee, his on-screen persona came from the soul. He brought his unrelenting powerfulness to the screen the same way he brought it to the streets of Hong Kong. In all five of his feature films, Lee’s on-screen persona, accented by his unique mannerisms, is unmistakable to the audience. If anything, Lee and Chan shared a need to establish a hero with whom the audience could easily identify. For Lee, it was the energized, stifled mannequin hero who blurted out the high-pitched “key-ops!” and grimaced at the camera with serious conviction.

Bruce Lee was a brooding controller, much like his on-screen persona. He knew what could make him a star on the screen, and he had no problem letting everyone know it. As a tough kid growing up in Hong Kong, Lee’s approach was “my way.” Period. After moving from secondary lead to star in Fists of Fury, Lee didn’t have to explain anything to the producers. He merely took charge of each project and acted accordingly. With prosperous box office receipts, no one complained.

As Jackie Chan’s career began to materialize, his on-screen persona distanced itself from Lee’s. It took almost ten years and ten films for this transformation. Many people still believe that Chan is still just a Lee imitator, but nothing could be further from the truth once Chan was able to get the same kind of control that Lee had over his productions.

It was a painful time indeed for Chan, and Master Yu’s training was just a precursor to the repetitious adversity that he would face. Whereas Sammo Hung became an understudy for Huang Feng, one of Hong Kong’s most celebrated action directors, and found work as a villain despite his portly figure, Jackie Chan couldn’t find anything to really suit him. In 1971, on the recommendation of an older classmate (actually the only girl in the group), Chan landed his first starring role (using his new name, Chan Yuen Lung) in the Young Tiger of Canton, but it was shelved and left uncompleted. Years later it would be released as Master with Cracked Fingers (among other titles), boasting extra scenes with a Chan look-alike. In 1973, Chan got his first shot as action director with The Heroine (also titled Attack of the Kung Fu Girls) in which he played a bit part. Chan played a bad guy to a female lead in Police Woman (1974) with an embarrassingly large patch of hair growing on one cheek! Though the experience was unmemorable, Chan became friends with the lead actor of that film, Chun Cheung-lam. Chan would eventually receive acting lessons from Chun in return for teaching him kung fu.

A seventeen-year-old Chan in Master with Cracked Fingers (1971). (Colin Geddes/Asian Eye)

Chan in John Woo’s Hand of Death (1975). That’s Woo behind Chan’s left shoulder. (Colin Geddes/Asian Eye. By permission of Media Asia Group. © STAR TV)

Chan appeared in a few other films as a stuntman and choreographer, but things just weren’t going his way. Accepting his measly role as a stuntman, Chan became almost impervious to pain, taking the hardest falls he could endure in hopes of catching the attention of the directors and fight choreographers. A few opportunities would open up, but Chan’s outlook on life needed a fresh approach. In 1975 he moved to Australia to stay with his mother at the American embassy for a year. Bored out of his mind, he would spend much of his time practicing on rooftops and finding odd jobs as a cook and dishwasher. Chan prided himself with the thought of really becoming a kung fu master by wearing himself out day after day.

Chan almost thought of calling it quits, however, until he got a call one day from producer-director Lo Wei. Lo was the man who discovered Bruce Lee and often claimed credit for his success, directing him in Fists of Fury and The Chinese Connection. Lee’s death in 1973 sent a scare into the Hong Kong film community. As Lee was the only Hong Kong star to gain international notoriety, film companies made a valiant effort to find his replacement. It seemed that anyone who could throw a punch or a kick was given a shot, and any variation of Bruce Lee’s name was put to good use for marketing. Lo became obsessive in the search and noticed Chan in Hand of Death (1975), an early kung fu outing for director John Woo (long before his rise to fame with hits like The Killer and America’s Broken Arrow). (Coincidentally, it was Lo who had directed The Heroine for which Chan action-directed.) In viewing the film, it’s difficult to see what Lo saw in Chan, since his role was nothing more than a bit player to spotlight the talents of Tan Tao-liang, another Bruce Lee imitator and one of the best martial arts actors of the time.

Lo Wei’s films were low-budget, weak affairs held together by ridiculous narratives. Fights are thrown in just to run down the clock for ninety minutes (the length of almost all Hong Kong films for no rhyme or reason). Lo did have an eye for talent, but he couldn’t direct or shape that talent. American karate star Chuck Norris was an example: he was wasted as an exploitive villain in Slaughter in San Francisco, a film Lo directed for Golden Harvest. As for Jackie Chan, his addition in 1976 to the Lo Wei formula didn’t work out as Lo hoped. Lo counted on Chan to carry the movie—something he just couldn’t pull off yet. Chan’s odd-looking features were matched with low budgets and poor scripting—not a winning formula. Chan didn’t have a chance to work on an on-screen persona because Lo was too busy experimenting with varying characterizations within the kung fu genre. Audiences didn’t know what to expect from Chan.

Unfortunately for Chan, he would have to prove himself in Lee’s mold—something that not only he couldn’t do, but no one could ever do. Thinking that he really had found the next Bruce Lee, Lo miscast Chan in New Fist of Fury (1976), with Nora Miao and Lo Wei reprising their roles from the Lee film, that actually being The Chinese Connection—not Fist of Fury. The film picks up where The Chinese Connection left off: Miao flees to Taiwan with the Japanese hot on her trail. Once again, the villainous Japanese set out to control all of the martial arts schools, and Miao must find a new leader in the form of Chan, who wants nothing to do with fighting nor caring about anything in general. Motivated by revenge, Chan eventually comes to her aid and leads the way to victory.

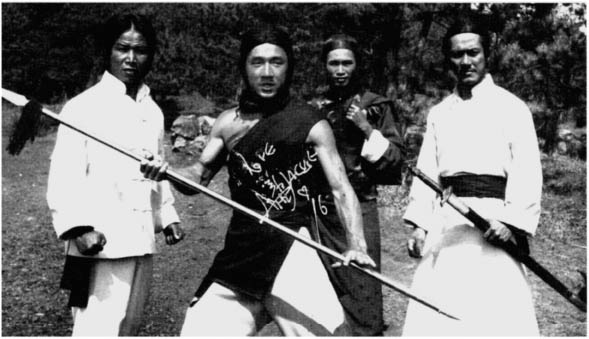

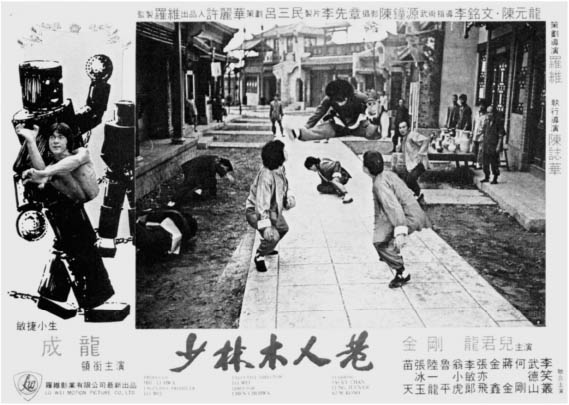

Shaolin Wooden Men (1976). (Colin Geddes/Asian Eye)

Chan’s Peking Opera training gave him the ability to perform showy acrobatics, and there was no doubt that he was a capable martial artist, but audiences were supposed to be watching the new Bruce Lee, and Chan’s less than charismatic portrayal didn’t do the film any favors. Chan tried to play the character with the same kind of confidence that Lee brought to the role, but he just wasn’t appealing enough to be taken seriously. Chan explains, “Nobody can imitate Bruce Lee. He [Lo] wanted me to do the same kick and the same punch. I think that even now, nobody can do better than Bruce Lee because he is the king of kung fu films in the audience’s mind.” (Interestingly enough, the only man who has been called the “Best Bruce Lee Imitator” is Sammo Hung, who perfectly copied his mannerisms and fighting style in the 1978 film Enter the Fat Dragon.) New Fist of Fury was so lackluster compared to its classic predecessor that many wonder whether Bruce Lee had more of a hand in directing the original than Lo. New Fist of Fury did mark the first time that Chan adopted his Chinese name of Sing Lung, a nonsensical translation meaning “becoming dragon,” or, if not entirely correct, “successful dragon.” It was modeled after Bruce Lee’s Chinese name of Lee Siu-lung, meaning “little dragon.”

Lo produced Shaolin Wooden Men the same year, but it didn’t make a difference. Using a surprisingly coherent script, Chan plays a worker in a Shaolin temple who has sworn himself to silence until he can avenge his father’s death. The only way he can leave the temple is to pass through a series of wooden robots animated as would-be attackers with springs, chains, and pulleys. The devices were actually nothing more than sensationalized versions of the wooden dummies invented by Wing Chun practitioners for training. To run the almost impossible gauntlet, Chan learns various styles of kung fu, making the point that the most successful martial artist is well rounded. Chan emerges victor over the wooden men and goes on to right the wrongs inflicted on his family. Predictable but flashy, the film did create a stir in the community because Chan was able to perform all five styles of animal kung fu as well as use the staff with perfect accuracy. Still, in the end it was just another film.

(Colin Geddes/Asian Eye)

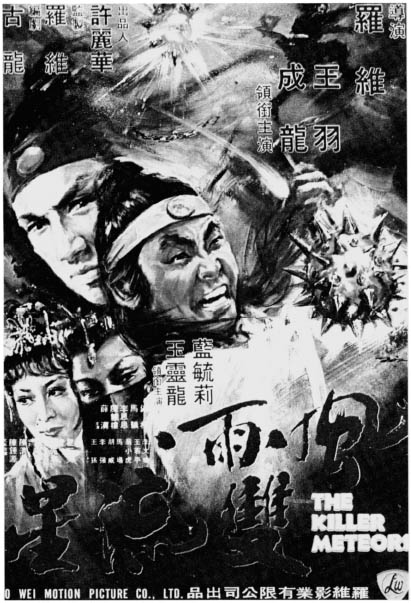

Unsure of what to make of him, Lo next cast Chan as a bad guy in The Killer Meteors (1977), giving yet another hero role for the downward-spiraling career of Jimmy Wang Yu. Wang Yu was second only to Bruce Lee in creating a strong persona with his One-Arm Swordsman role. Chan merely laughs into the camera and performs a few flips before attacking the stiff Wang, who had no formal martial arts training. It wasn’t much of a role, but Lo thought that Wang Yu’s presence would boost Chan’s appeal with the audience. He was wrong.

Going downhill even further, Lo directed Chan in the completely absurd To Kill with Intrigue (1977), essentially a Chinese melodrama, or “weepie,” peppered with kung fu fights. Chan plays a stone-faced survivor of a massacre that left his family dead, and he must contend with the killer, who has fallen in love with him. The only problem is that Chan is bent on finding his pregnant girlfriend, whom he abruptly pushed away at the beginning of the film. As premise-based as the plot already is, it becomes disjointed by more characters, belonging to different martial arts factions, that the audience is supposed to remember. The film brings the love-war relationship to a head when Chan and his female captor work together to battle the real bad guys. A cruel training regimen pits Chan against her in a series of tests. After defeating Chan, she tells him to train and face her again. Chan comes back for more and loses a second time, so she puts a hot coal down his mouth as punishment! With a raspy voice, the determined Chan goes back into training to try and win a third match. His lesson yet unlearned, this time she burns the side of his face off! After figuring that Chan isn’t going to give up, the lady whirlwind gives Chan a cupful of her own blood, magically transforming him into a kung fu master!

Jackie’s Names

| Born: | Jacky Chan Kong-sang |

| Opera name: | Yuen Lau (Yuan Lau) |

| First film name: | Chan Yuen Lung |

| Lo Wei name: | Sing Lung (English: Jacky Chan) |

| Golden Harvest name: | Sing Lung (English: Jackie Chan) |

| Other names: | Shing Lung, Cheng Long |

Snake and Crane Arts of Shaolin (1977). (Colin Geddes/Asian Eye)

To make matters worse, Lo directs the film like any other pedestrian effort, using low angles to shoot supposed flying sequences, reversing the film for flying backward, and making up weapons, such as a club the size of a man with a face painted on it. Despite these exploitive mechanisms, the film does have some intricate fight choreography that really shows audiences that Chan can fight, perform acrobatics, and leap from tall trees in a single bound. The final fight sequence is undoubtedly the best Chan moment, leaving one to wonder why the rest of the film wasn’t as good.

Trying to find some kind of hero within Chan, Lo began grabbing at straws. Chan was paired with Lee’s old costar James Tien in several films, and it seemed that the only experimentation his character would undergo was a change in wardrobe and hair styles. Sporting a Shaw Brothers-like ponytail, Chan made his dream project, Snake and Crane Arts of Shaolin (1978). Like most kung fu films, the opening credits show off the star’s talents, and Chan puts on an incredible show using a spear, broad sword, and tonfa. Chan plays a lone kung fu expert roaming the countryside in possession of a book that contains the secret of the snake and crane arts, naturally. Chan spouts off plentiful wisecracks and must champion numerous entities wishing to get their hands on the book. He eventually teams up with a tomboy, who has her own idea of how the book should be used, and together they must battle their way to the ending, which unfolds the mystery of the book and its deceased writers.

This film contains the best fight choreography before Chan’s Seasonal films, and the buddy concept works quite well amid the usual Lo(w) Wei production values. Whatever Chan’s minor deficiencies in the martial arts department, he was formally trained in the use of classical Chinese weapons (a staple of Cantonese opera) and was able to put these abilities to good use. Despite the energy put into the film, it met with dismal returns at the box office due to a lack of advertising.

With Lo Wei giving the final go-ahead for a comedy, Chan and friend Chen Chi-hwa (Snake and Crane’s director) created Half a Loaf of Kung Fu. The kung fu film market was so overloaded with every possible variation of kung fu style usage and of plots based on rivaling clans, revenge, and betrayal, that Chan saw the need for a parody. Almost the entire cast from Snake was used again, and famed comic character actor Dean Shek was brought in to lighten things up even more. Over the film’s opening credits, Chan dresses in various costumes, sets up typical scenes inherent to the kung fu genre, and defuses them with humorous antidotes. In one sequence a bare-chested Chan performs a series of movements, jump-cutting to a shot of a wooden dummy. When Chan comes upon the device, it stands only one foot high, and he kicks and punches at it as though it were full size.

Chan remains deliriously goofy throughout the entire film, while most of the supporting players stay within their conventional molds. Borrowing from Chinese lore that ascribes the power of flight to warriors, kung fu films would often allow its players to leap far into the air, only to land just a few feet away from their intended combatants. When Chan jumps into the air, he flaps his arms like a chicken and squawks at his opponents. Before the film can finally settle down into its serious plotline, a duel has Chan using the villain’s hairpiece as nunchakas in typical Bruce Lee fashion. Chan, whose character doesn’t know kung fu, is even tricked into learning the “steel finger,” a phony technique that doesn’t quite work for Chan when put to the test. In one scene, Chan entirely breaks out of character with a laugh as he walks offscreen.

Half a Loaf of Kung Fu is more than worth a look for fans seeking Chan’s first real attempts at comedy, and despite the in-your-face approach, some of the scenes are quite funny. When Lo saw the film, he quickly shelved it—only to release it in 1980 when Chan’s popularity was catching on.

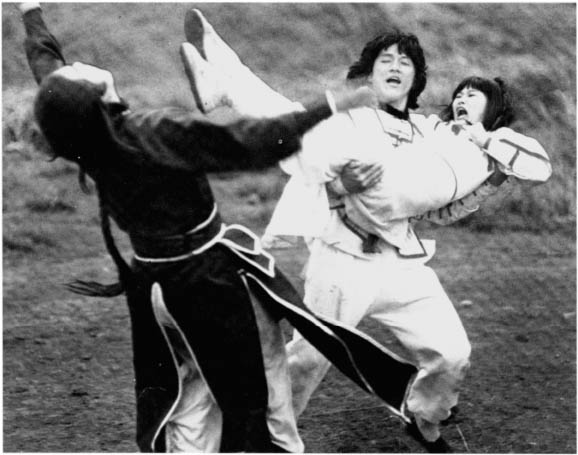

Chan uses his lovely co-star as a weapon in Half a Loaf of Kung Fu–a gimmick he would improve on fourteen years later in City Hunter. (Colin Geddes/Asian Eye)

At this point in time, Chan and Lo had nowhere else to turn but to each other. Chan was on a longterm contract, and Lo had no one else in his stable of actors to use as a worthy lead. Lo would probably have had more success if he had stayed with Golden Harvest instead of venturing out on his own, but by 1978, it was too late. The damage had been done, and the two had no other choice but to keep churning out kung fu films.

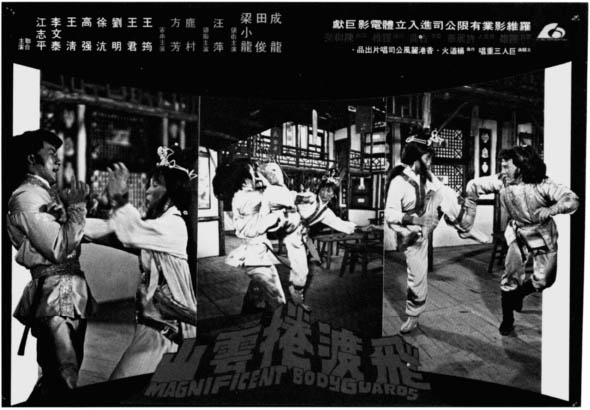

Trying yet another approach, Lo paired Chan with two other heavies, James Tien and Bruce Lee-alike Bruce Leung, for a group-protagonist kung fu flick entitled Magnificent Bodyguards. Boasting some fairly amateurish special effects, the low-budget film was released in 3-D to enliven the shoddy plotline, which has our three heroes escorting a rich family carrying a sick relative to safety. Their journey takes them into harm’s way at every turn. They meet up with Chinese natives, monks, and an evil king who controls their safe passage. Midway through the film, Lo’s production company stumbled across the score for Star Wars, so they pull several tracks for the film’s cheapo soundtrack. Star Wars’ famous trench-battle music even plays over the film’s final fight!

Aside from the colorful costumes and corny plot twist at the end, the only two parts of this film worth watching are Leung’s excellent kicks and one little piece of dialogue. When the monks can’t fight off the trio, they escape behind a series of corridors, and ring a group of large bells overhead to knock out their adversaries. “Well, all of them were pretty tough fighters, but none of them could survive my bells!”

Upset that Chan couldn’t make a decent kung fu comedy, Lo decided to direct him in Spiritual Kung Fu (1978). While Lo’s direction allows for Chan’s comic approach to shine, the film tries too hard to be a comedy and fails at almost every turn. Chan plays a lonely temple worker who asks to watch over the library and guard it against oncoming thieves bent on stealing the temple’s secrets. When five red-haired female spirits show up, they agree to teach Chan the art of “spiritual kung fu,” which gives him the necessary skills to find the thief who stole an important book from the library. Lo’s idea of comedy has Chan urinating on an inch-high spirit and cramming small animals down the front of his pants. As the film progresses, the film becomes completely uneven, settling down into the doldrums of typical kung fu fare.

Lobby card for Magnificent Bodyguards showing Chan’s not-so-magnificent hair. (Colin Geddes/Asian Eye)

Dragon Fist (1978) is arguably the best of Chan’s Lo Wei films, despite the fact that it’s a serious kung fu outing. The well-structured script injects depth and emotion into the common revenge story. Although this would have made the perfect Bruce Lee vehicle, audiences get the chance to see Chan act as a straight man. During a martial arts competition, a master from a rival clan comes to challenge the master putting on the competition. The rival not only defeats him but kills him in the process. When one of the students (Chan) returns to find his master killed, he takes the master’s wife and daughter along with him to settle the score. But when he finds the rival master, he sees an honorable warrior who acknowledges his wrong in killing and has even cut off his own leg in repentance. Chan’s honor is tested when another clan forces him to fight the clan that he has forgiven. Chan’s fierce bravado, several plot twists, and top-notch fight choreography make Dragon Fist a worthy addition to Chan’s early filmography.

It didn’t matter what film it was—Lo just couldn’t make Chan into a star. Chan’s Peking Opera training made him more of a dancer, not a seasoned fighter. Still, for Chan, there was a spark of interest in filmmaking: Lo slept through many of the films that he was supposedly directing, giving Chan the chance to direct some scenes himself. By 1978 Lo had just about given up, and when he began to run out of money, he was happy to loan Chan out to Seasonal Films when the opportunity arose. Lo’s shortage of money prevented Spiritual Kung Fu and Dragon Fist from being released at first, but the two would come out in between the two Seasonal films that Chan would make.

1 American release titles are used here, with the original Hong Kong titles in parentheses—since these titles are what can be found through video outlets. The alternate titles of Lee’s films can be confusing: what was The Big Boss in Hong Kong became Fists of Fury in America, while Fist of Fury was retitled The Chinese Connection.