City Hunter. (Colin Geddes/Asian Eye. By permission of Media Asia Group. © STAR TV)

Sammo Hung and Stanley Tong are the only two directors who could do what Chan wanted them to do in the first place. They both commanded their film sets with firm authority—taking the pressure off Chan, whose mind was left to rest on acting and action. Tong brought structure and attention to his work, and Chan respected his drive as well as the amazing personal similarities between the two. Hung’s experience spanned the course of nearly two hundred films, with jobs as producer, actor, fight choreographer, and director. “Jackie never once challenged Sammo’s direction. I remember asking Yuen Biao if he ever second-guessed him. He said, ‘No one does. Not even Jackie. Jackie is my big brother; Sammo is everyone’s big brother. Nobody questions big brother!’ ” says Wheels on Meals vet Keith Vitali.

As long as Chan could see that the director was in control at all times, there was no need for intervention. Control is a factor of Chan’s filmmaking, and that is the key to using him instead of being used by him. Directors Tsui Hark, Wong Jing, Kirk Wong, Lau Kar-leung, and Gordon Chan were put to the test. All of them failed for one reason or another.

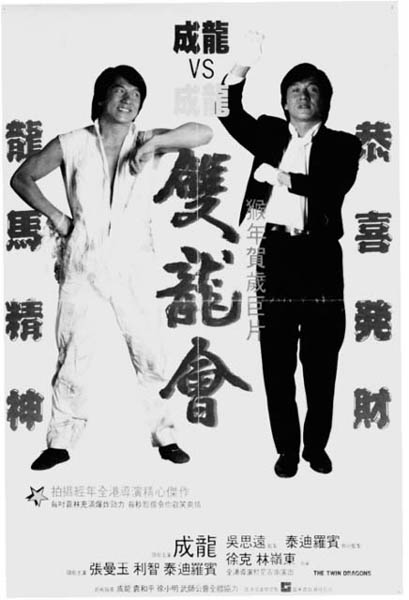

As a charity effort for the Hong Kong Film Director’s Guild, Twin Dragons (1992) was a comedic fluff piece, with Chan’s amiable charm showing through with not one but two characters. Born to a prominent family, two twins are separated at the hospital by a crazed killer on the loose. One twin ends up with a town drunk and grows up to be an auto mechanic, complete with ponytail, earring, and smoking habit. The other twin grows up with his family in America and becomes a praised composer and pianist. The Prince and the Pauper retelling soon comes into full swing when composer Chan comes to Hong Kong for his first big concert away from home. There he runs into the mechanic, also played by Chan, who has managed to land himself in quite a mess with a group of unruly mobsters. Both Chans are connected to women (Maggie Cheung and Nina Li-chi) that are better suited for each other’s twin, leading to the endless mistaken-identity gags that form most of the film’s humor. After the two twins reunite, they make a pact to get the mechanic Chan out of trouble and deal with their lady friends accordingly.

Twin Dragons. (Colin Geddes/Asian Eye. By permission of Media Asia Group. © STAR TV))

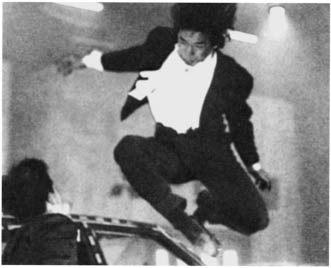

After an incredible display of Chan’s kicking power in the beginning, the film’s action settles down to a more restrained level until the climactic showdown in a car testing center, where Chan’s team takes over to full effect. Chan rips through assorted props that one would find in such a place, and he must fight Shaw Brothers veteran villain Wang Lung-wei (Project A II).

In all fairness, the film is cute, and some of the one-note humor’s scenarios are slightly amusing. There is the obvious fantasy element of seeing two Chans on the screen at once, and the whole film was made with good, clean fun in mind. Whenever one Chan does something, the other feels it and reacts to it. This part of the gag quickly loses its novelty, but Twin Dragons was a limited idea in the first place. At least the film does make good use of this device when the nonfighting Chan must use his twin to throw his punches for him.

Part of the reason that Chan wanted to do this film was to experiment with special effects, using the master Hong Kong director of such, Tsui Hark. “Compared to Hollywood special effects, Twin Dragons is crap!” states Chan. “After that, I’m totally disappointed with Hong Kong special effects. This is why I’m not going to use special effects in my films again, except from the people in Hollywood.” Surprisingly, though, most of the effects featuring both Chans on the screen at the same time are comparable to some of Hollywood’s bigger-budgeted efforts, like Big Business (1988).

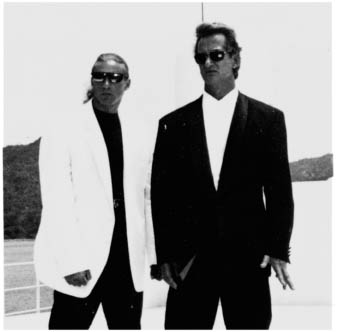

Twin Dragons directors Tsui Hark and Ringo Lam have both turned out some of the greatest Hong Kong films on their own. Tsui’s films are politically charged poems of Chinese enlightenment, while Lam stays close to hard-edged police dramas set in murky urban locales. Together they trade in their personal styles for that of the loosely structured comedies they made at the start of their careers—both of them directed sequels in the Aces Go Places series. Sadly, neither director’s vision really shows through, and the only highlights are the action sequences and occasional charm by Chan and company.

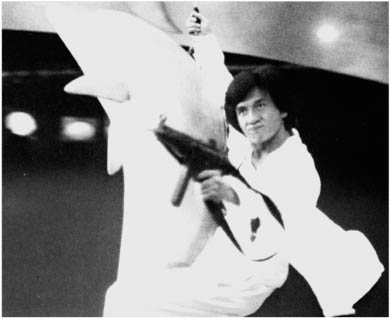

Twin Dragons was also a reunion of sorts, since Ng See-yuen served as producer and Yuen Woo-ping assisted in the film’s fight choreography. More than fifty Hong Kong directors made cameos in the film, including Wong Jing (City Hunter) as a supernatural healer, Lau Kar-leung (Drunken Master II) as a doctor, Kirk Wong (Crime Story) as the crazed killer and John Woo (Hand of Death) as a priest. When Chan first enters the car testing center, the three guys sitting at a table playing cards are Tsui Hark, Ringo Lam, and Ng See-yuen. Twin Dragons was inspired by the Jean-Claude Van Damme film Double Impact. (Van Damme has made a film each with Ringo Lam, Maximum Risk, and Tsui Hark, Double Team.)

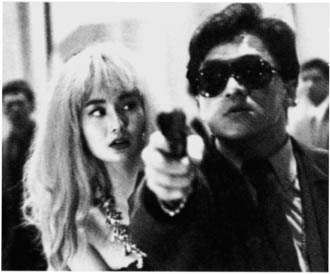

Maggie Cheung and Chan. (Colin Geddes/Asian Eye. By permission of Media Asia Group. © STAR TV))

Chan in action. (Colin Geddes/Asian Eye. By permission of Media Asia Group. © STAR TV))

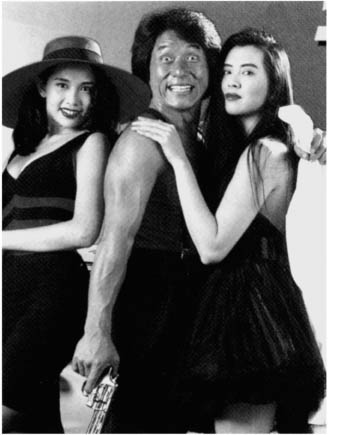

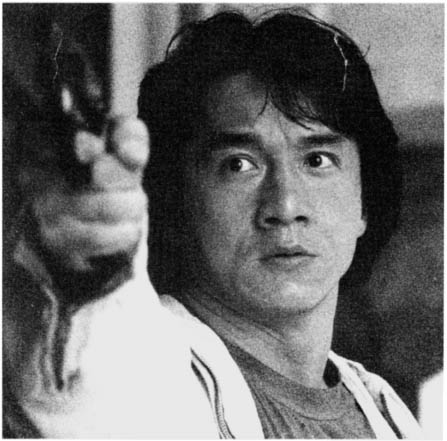

Due to Supercop’s marginal success, Golden Harvest urged Chan to keep costs down and make a couple of smaller films. City Hunter and Crime Story could not be any further apart in tone, action, and direction. Based on the manga (comic book) and associated animation series, City Hunter (1992) seemed like the perfect vehicle with the Japanese market in mind. Chan’s character, Ryu Saeba, is a womanizing detective whose nifty theme music appears whenever he does anything. Chan’s films stretch the notion of plausibility, but City Hunter allowed him to go into pure escapism. “We wanted Wong Jing to direct City Hunter because he is real good at keeping costs down and knows how to control budgets. Besides, he knows how to direct comic book movies,” says Chua Lam, City Hunter’s producer. Wong is Hong Kong’s Roger Corman, a low-budget, prolific purveyor of madness. If Wong’s name appears in the credits, the audience should know better than to look for continuity or balance. Even with his scattershot efforts, Wong has managed to direct some winners, most notably Chow Yun-fat’s God of Gamblers (1989) and its larger-scaled sequel.

Kirk Wong, as Twin Dragon’s crazed killer, would re-enter Chan’s world with Crime Story. (Colin Geddes/Asian Eye. By permission of Media Asia Group. © STAR TV))

(By permission of Media Asia Group. © STAR TV)

City Hunter also brought together a great international cast, including Japanese supermodel Kumiko Goto, Australian martial arts actor Richard Norton, British martial arts actor Gary Daniels, and Hong Kong’s own female superstars Chingmy Yau Shuk-ching (Wong Jing’s longtime girlfriend) and Joey Wang Jo-yin (God of Gamblers). Golden Harvest was originally going to use Keith Vitali in the role of the terrorist leader “Big Mac” Donald, but Chan wanted to use Richard Norton. At first Norton declined, noting Hong Kong’s long, exhausting shoots, but he eventually came around when they met his price. Norton had worked with Wong Jing before, on the film Magic Crystal (1987), which made things a lot easier.

Daniels was working on a low-budget American film at the time, when a call came in from Willie Chan. Daniels needed to be in Japan on a Fuji cruise liner within days, or the ship and the City Hunter opportunity would be sailing without him. Having heard of Chan, the low-budget director let Daniels finish his shooting early. Daniels recalls, “I had been sending packages and letters to Golden Harvest for years, and I would always get these polite letters saying we really liked your tape, but we don’t need anyone right now. I couldn’t believe I was going to work with Jackie Chan!” Casting is not a difficult process for Hong Kong films: they just keep calling until they get someone to fill the part.

City Hunter and Half a Loaf of Kung Fu have a lot in common. They are both parodies of sorts, and characters can simply run wild through the structureless celluloid, even jumping out of character if need be. As for the plot, or lack of one, it can be summed up in two sentences: Chan and his assistant (Wang) must bring back the runaway daughter (Kumiko) of a wealthy Japanese newspaper tycoon. They follow her onto a cruise liner, where a group of terrorists are intent on kidnapping the ship’s prominent businessmen passengers for ransom. Except for some of the more complex gags in the film, City Hunter is as close to watching a Keystone comedy of old as Chan gets. The exaggerated facial expressions, daffy walk, and lighthearted score give Chan’s usual charm a freshness. Sure, it’s goofy child’s play, but there is never a dull moment amid the colorful sets and surprisingly universal sight gags. Chan’s City Hunter bears little resemblance to the manga on which it was based, except for Wang’s recurring thought of hitting Chan on the head with a large sledgehammer via a dream sequence and a quick gag at the end.1

Chingmy Yau Shuk-ching, Chan, and Joey Wang Jo-yin. (Colin Geddes/Asian Eye. By permission of Media Asia Group. © STAR TV)

It took three and a half months to shoot City Hunter—two weeks on the cruise ship, and the rest bouncing between the Golden Harvest and Shaw Brothers studio lots. Wong would direct the comedic scenes, Chan would direct the fight sequences, and Ching Siu-tung (A Chinese Ghost Story) would orchestrate the effects of the famed Streetfighter II scene. The problem with Wong Jing is that he makes so many films in a year that he doesn’t really care about any one in particular. Unless he was directing, Wong would spend much of his time on the ship asleep. In the world of low-budget filmmaking, however, Wong Jing has never had anything to worry about. “Wong has the Midas touch: everything he directs does well at the box office,” notes Daniels.

While Chan looks so happy on-screen, he hated the film and even said that he would have liked to do a sequel if he had directed the first one his way. If one can accept the comic book aspect of the film, the main problem with City Hunter lies in its inability to find an audience. On the surface, it’s a tame cartoon with a basic storyline and flashy characters. In depth, however, like with many of Wong’s other films, offensiveness and tone shifts prove too problematic for their own good. AIDS jokes, homosexual stereotypes, sexist gags, and gratuitous violence detract from the film’s good-natured intentions. Does a film based on a comic book really need people to get razor-sharp cards stuck in their heads or have a high body count, considering that children are going to be the main audience?

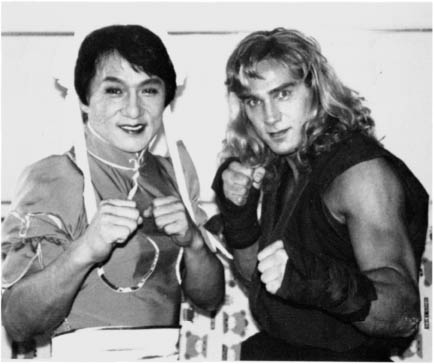

Gary Daniels and Richard Norton head an international cast in City Hunter (Courtesy of Gary Daniels).

With that said, there are some classic moments. The main conflict of the film stems from the terrorist takeover of the ship, much like in the American film Under Siege. Making better use of the setting, Chan and Kumiko run inside of a movie theater showing Game of Death. After disposing of several gun-toting terrorists, Chan faces two giants, who prevent him from even landing a punch. When all hope seems lost, Chan takes a hint from Bruce Lee’s fight with Kareem Abdul-Jabbar to get the upper hand with his towering opponents. Jackie Chan has worked hard to stay away from the stereotype of being just another Bruce Lee clone, but it was nice to see that he could take a tip from the Little Dragon when need be.

Chan and Daniels, in Streetfighter II wardrobe, stop for a quick pose. (Courtesy of Gary Daniels)

Chan’s first meeting with Gary Daniels. (Courtesy of Gary Daniels)

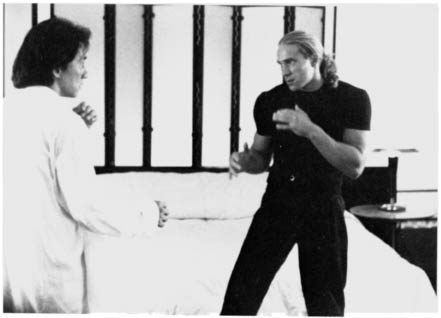

Chan’s other concern is playing for the affections of Joey Wang, which leads to a fight with Gary Daniels when she tries to make Chan jealous. The duel is fairly noteworthy and comical, but Chan was supposed to be the one to shine, so Daniels wasn’t given the chance to display any of his own acrobatic abilities. After Daniels had left, Kenneth Low was inserted for an overhead shot without Daniels’s knowledge. If one looks closely, one can clearly see Low’s face under a long blonde wig. That blonde hair of Daniels was precisely what landed him the job in City Hunter anyway, since the best gag in the film is a dreamlike sequence where the characters from the Streetfighter II arcade game come to life. Daniels is a mirror image of the game’s Ken, two Hong Kong disc jockeys known as the Hard and Soft Team played Guile and Dhalsim, and Chan himself played E. Honda and Chun Li. The movements and sound effects emulate the game with complete accuracy, something that the American Streetfighter, starring Jean-Claude Van Damme, did not.

In Half a Loaf of Kung Fu, Chan uses his female costar as a prop, flipping her around his body while she throws kicks and punches at the enemy. Fifteen years later Chan uses Chingmy Yau (an agent assigned to the ship) in a similar fashion, only this time she is shooting all of the guns fastened to different parts of her body. When a Taiwanese commando unit comes to the rescue, the only thing left is a climactic battle with Richard Norton, shot on the Shaw Brothers lot. Using conventional means, Norton assails Chan with fists and feet, sticks, and, finally, whips. Chan, on the other hand, breakdances around Norton’s actions, even executing a gymnastic iron cross move when given the chance. Although Chan did this particular move himself, some of the action was doubled by a Mainland Chinese gymnast. Again, these days when Chan doesn’t have the time to prepare himself for his stunts and have his crew around him for support, doubles will be used more readily. In shooting two films back to back, “Jackie would show up around one o’clock in the afternoon, do a shot, and then fall asleep, before he had to go to the other set at night,” remembers Daniels.

Three years later, Wong Jing would end up directing a parody of Jackie Chan himself in High Risk. Hong Kong pop star Jacky Cheung plays a pretentious action star whose fame and fortune have diminished his will to perform his own stunts. Jet Li plays the character that stunt-doubles for him, though Li was doubled in the scenes he was supposed to be doing for real. Jacky Cheung’s manager in the film is the spitting image of Willie Chan, though all of the characters in the film are played so silly that any harmful statement regarding Jackie Chan’s stunt-doubling was surely unintended.

Imagine bringing the cold hardships of the real world to Chan’s Police Story character and you’ve got Crime Story (1993). Instead of running around in a loose shirt and slacks, Chan has the stuffiness of a detective bound in a tie, pressed pants, and jacket. He doesn’t kung fu everyone into submission, either, because his world uses guns to proclaim authority. Even his typical “man versus himself” conflict reveals a darker side here. He has to see a police psychologist on a regular basis to keep his sensibilities despite the anxieties that plague his day-to-day work. All of these great character traits would have made for an interesting departure from the Jackie Chan genre, but forty minutes into it, the only thing that remained was the blue-tinted look of the film.

In 1991 when Chan was filming Twin Dragons, one of the easiest directors to cast as an actor was Kirk Wong Chi-keung as the film’s villain, a role that he played countless times during the eighties. Wong’s directing career was on shaky ground at the time, and he had this idea of bringing a true crime story from 1990 to the screen. In discussing the idea, Chan liked the story very much, but Wong had Mainland Chinese kung fu star Jet Li in mind for the role. When Li left Golden Harvest after a falling out with director Tsui Hark, Wong’s script was dead in the water. Thinking it over, Chan expressed interest in taking the lead because he was curious about the film’s background and wanted another shot at a straight acting job.

What Chan didn’t understand was Kirk Wong’s style. In 1981 Wong unleashed The Club, an exploitive gangland thriller using kung fu star and ex-triad member Chan Hui-man in the lead role. From this directorial debut, it was apparent that Wong’s vision revealed the darker side of protagonists caught up in personal conflict. Moods are set by exposing the underbelly of the modernized world, where neon lights dance across the smoke-filled sky. Much of the sound used in his films stems from the hustle and bustle of normal city life such as the vibrations of a jackhammer, the clamor of a crowded street, and the crackling pops of food being fried by local vendors.

Violence is not abundant, but the emotions that drive what is on the screen is even more heart-pounding, if not entirely conceivable. In Gunmen (1988) a child blows away the lead villain with a blood-spouting head shot. In Rock n’ Roll Cop (1993) a man splatters a cat against a wall with his bare hands. In Health Warning (1984) a man is stabbed in the back with rabies-infected syringes. If Chan had fully understood Kirk Wong’s films, he probably would not have appeared in Crime Story at all, much less modify the film to suit his own needs.

The film is based on the 1990 kidnapping of a high-profile land developer who had also been kidnapped just two years before. The land developer calls again for police aid, and Chan is assigned to the case. The kidnappers demand US$60 million for the developer’s safe return, but Chan’s team quickly figures out where the money is going. The only problem is that one of Chan’s team, a decorated police officer he admires (played by veteran character actor Kent Cheng), turns out to be one of the culprits. When he and Chan follow a lead to Taiwan, Chan becomes suspicious of Cheng. Chan is forced to carry out his own personal investigation upon their return to Hong Kong. The plot shifts from the kidnapping itself to the cat and mouse game between Chan and Cheng.

Along with the changing of central plotlines, Chan apparently took the helm away from Wong. Though he didn’t work on the film, Edward Tang has noted that Chan was not happy with the subplot involving his character’s mental strain. Thus, after two scenes where Chan and the police psychologist bump heads, she is excised from the film altogether. An awkward relationship was supposed to have surfaced between the two, revealing even more of Chan’s inner conflict, but this whole plot strain was completely done away with.1 “Wong made the film look too serious with the blue and discolored lenses; Jackie just wanted to lighten things up,” remembers Golden Harvest producer Chua Lam.

In the beginning of the film, Wong’s trademark shooting style is left intact, with hand-held cameras, elaborate crane shots, and blue-tinted lenses. The violence is heavy hitting without being over the top. As for Wong’s unrealistic, yet original violent exercises, there is a scene where the kidnappers must revive a woman with jumper cables while revving up the engine! Even Chan’s head receives a bloodletting gash when his car rolls over.

When sex is used in Wong’s films, it is often not as a show of love, but of aggression. There is a scene in the film where Cheng and his mistress grope each other in an elevator. This is followed by a heated scene in an underground parking lot. When Chan saw this, he snapped at Wong that this was not something that could appear in a Jackie Chan movie. In the release these seedy proceedings are faded out into the scene that follows.

Chan’s character is at first afraid, hesitant, and shaken when drawn into violence. During a shoot-out at the beginning of the film, Chan unloads his gun from behind a car, while a child is not more than three feet in the background. The sprays of gunfire lighting up the streets of Hong Kong preclude him from saving the child—only himself.

With the police psychologist subplot taken out, however, Chan suddenly becomes more physically courageous. Two scenes show the incredible contradiction between the sides of his character. First Chan goes to Cheng’s mistress’s club, where many of the kidnappers are there to greet him. They throw wine on him and push him around, and Kenneth Low gives him a nice, big smooch on the lips to agitate him. Chan merely walks away from the encounter without so much as a punch or a kick staying within the character the film originally portrays. Not fifteen minutes later, however, when he brings in one of the bad guys, they tear up police headquarters with normal Chan fare. After finishing him off, Chan does a forward somersault to land himself in front of a water fountain to quench his thirst. From there on, Kirk Wong’s style and his control of the film is lost to Chan.

The film does have some great stunts, and although they are not as big as Chan’s usual set pieces, they should keep fans happy. After the change in characters and action, the finale, thankfully, returns to Kirk Wong’s style, although it bears more resemblance to Sammo Hung’s Heart of Dragon climax. Chan’s inability to save the kidnapping victim leads him to a dilapidated locale in Kowloon, where he tries to make sense out of a code associated with Cheng’s part in the crime. Little does he know that he is standing in the kidnappers’ lair and must face off against nearly ten men armed with guns, shovels, chairs, and anything else they could get their hands on. Heart of Dragon’s cinematographer, Arthur Wong, worked on this film to pull off some of the fantastic shots, particularly in this end sequence. Aside from Kenneth Low, Sammo Hung’s kung fu man Chung Fat also makes an appearance as one of the kidnappers. Although Chan choreographed the film, he let his Snake and Crane Arts of Shaolin director Chen Chi-wah do all of the fight directing. Chen’s style brings back more of the brutality, which complements Kirk Wong’s vision.

After this amazing encounter, the entire building blows up due to a gas leak. Chan once again goes against his original characterization when one of Cheng’s men is burning to death. Instead of trying to save him, Chan shoots him to death to end his misery. Then, in completely contradictory behavior, he tries to aid Cheng’s escape from the building after Cheng had tried to trap Chan and a small child there to seal their fates!

For fans wishing to see what Wong should have done with Chan’s character, check out Rock ‘n’ Roll Cop, where the protagonist walks attentively towards his enemy with a deathly stare. After a blistering fight, he leans the villain up against the wall and blows his head off. A word is never uttered during the entire confrontation. Wong’s style may not necessarily suit America—nor Jackie Chan, for that matter—but it echoes the true nature of violence and the fevered pain that drives it. In Hollywood the good guy and the bad guy stand there and talk to each other for a few minutes before the bad guy gets shot in the arm. Then he gets up to attack again, forcing the good guy to finally kill him. Is this how it would really happen?

After Crime Story the Hong Kong film industry had its new genre to tap into: true crime. This genre produced dozens of films over the course of 1994. Wong released Organized Crime and Triad Bureau (one of the first Hong Kong films marketed to the non-Asian market during the nineties). With renewed interest in his gritty filmmaking style, Wong moved to America and presently resides in Los Angeles. He will be helming The Big Hit, an action comedy, for Wesley Snipes’ new company.

(By permission of Media Asia Group. © STAR TV)

In 1991, elitist New Wave director Tsui Hark made a daring move by bringing the kung fu film back to Hong Kong cinema with Once Upon a Time in China. Gone were the days of senseless fights and lackluster production values. The film propelled Mainland Chinese star Jet Li to stardom playing the young Hwang Fei-hung, and the plot served as a metaphor for the relationship between Hong Kong and Britain. As for the action, Tsui’s arty take on the matter meant using wires to accent the amazing talents of Li and his costars. Five sequels and a television series have been made, and for the next few years, period-piece kung fu films were back in the swing of things. As the genre was recreating itself, the cycle would begin again with serious, comical, and parodic examples.

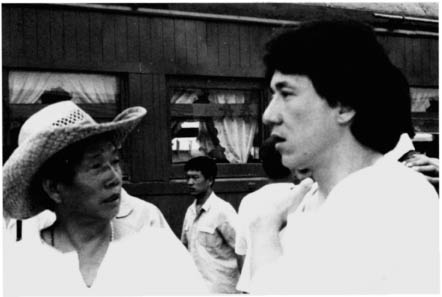

Director Lau Kar-leung, sporting a cowboy hat, discusses the opening train scene of Drunken Master II. (Courtesy of Edward Tang)

During this new period of kung fu films, Chan’s only involvement was singing the Hwang Fei-hung theme song for Once Upon a Time in China II (1992). After Supercop many thought that Chan’s martial arts days were over, but after a little prodding, a sequel to his Drunken Master couldn’t have come at a better time. By the end of 1993, Hong Kong audiences were ready to move once again.

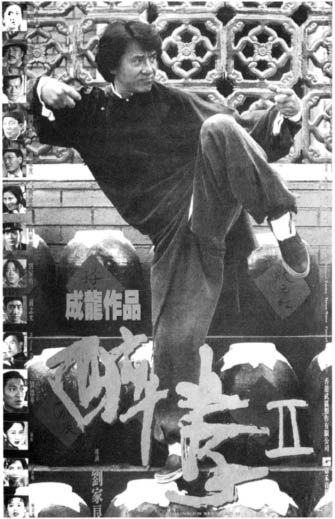

As if he had been resurrected from the kung fu grave, Shaw Brothers maestro Lau Karleung was once again put in the director’s chair. Lau was a direct descendant of the real Hwang Fei-hung, and after all, he was a kung fu master of Hung Gar. Although Yuen Woo-ping and his brothers were still working in kung fu films, Drunken Master II needed to get back to the foundation of real kung fu, with no wires or special effects. In all of Lau’s early kung fu films, the audience was treated to just that.

His direction in Drunken Master II (1994) gave Chan’s moves as well as his own the realism of freestyle kung fu, and when Chan actually performs drunken boxing, it’s done to perfection. “How can you do more than ten jump kicks in one jump? The people from the ground can jump ten stories high? That’s wrong! So this is why I am angry and wanted to make one kung fu film to show some of the other directors the traditional, original way,” Chan explained to Colin Geddes of Asian Eye.

The main problem was that Lau was too much of a firm stylist, unlike Chan. He was also in his sixties and had not worked with a budget so large in quite some time. The majority of the film was shot in Shanghai, where Lau helmed all of the film himself. “Chan felt that Lau’s thinking was ‘old-style Chinese’—completely different from his own,” says Edward Tang, who contributed to the script and served as assistant director. As a show of respect to Lau, Chan didn’t change a thing while they were shooting in Shanghai. Upon returning to Hong Kong, however, Chan cut over ten minutes of finished footage and directed 30% of the completed film himself. Chan’s most apparent touch was the extended duel between himself and Kenneth Low. Reminiscent of his Young Master days, Chan not only used some of his drunken moves but added a touch of breakdancing to the fight montage.

Drunken Master II broke all box office records across Asia—and it silenced fans who questioned whether Chan could still cut the fight action. The films before Drunken Master II—Supercop, City Hunter, and Crime Story—had their moments, but no one thought Chan could perform some of his most blistering martial arts action in years. And there was no doubt: this was 100% Jackie Chan. No quick cuts, wire effects, stunt doubles, or manipulation of film speeds. Fans and critics alike hailed the film for its energy, action, and Chan’s maturation as an actor. Although the modern kung fu genre was coming to an end, Chan gave it a graceful send off.

After Rumble in the Bronx, Chan rushed to his next project, a quickie racing movie that was supposed to have been centered on the illegal racing that goes on in Hong Kong. When some Japanese investors got wind of the project, however, Thunderbolt (1995) turned out to be the most expensive Jackie Chan film ever made (until Mr. Nice Guy) with a budget of $20 million. Like many Hollywood stars, Chan has always admired racing, and he has entered several competitions himself to raise money for charity. He even prides himself as a major car collector. In 1994 he hosted the Macau Grand Prix along with many of Hong Kong’s top female film stars.

Upset by Chan’s redo of the film, Lau returned with Drunken Master III just four months later. Lau spent most of his money on Andy Lau, who had portrayed the general’s son in the previous film. With poor production values and a nonsensical plot, Lau’s outing was nothing more than an attempt to cash in on Drunken Master II’s success.

Director Lau even used brother Lau Kar-fei (Gordon Liu), the bald-headed hero of many Shaw Brothers classics, to add to the film’s appeal. Lau’s student Mark Houghton appears in the third film, playing one of the main villains. Originally, Houghton was supposed to have been one of Chan’s foes in Drunken Master II, but Lau took him away from the Hong Kong set when he found out that his version of the film was cut.

Lau fell ill with stomach cancer, and has been quietly living in Singapore. Fortunately, he has recovered, but with no word as to if and when he will go back to directing. His best films are 36th Chamber of Shaolin (a.k.a. Master Killer), Legendary Weapons of China, Heroes of the East, and My Young Auntie.

The most puzzling aspect of Thunderbolt is its use of three different directors. Gordon Chan had worked as a scriptwriter (he coscripted Dragons Forever) and effects supervisor before he became a director himself in 1989. Action was not his game, since he directed mostly dramas and comedies. For the majority of Thunderbolt, Gordon Chan was in charge of handling the dialogue. For the racing sequences Frankie Chan was brought in, due to his knowledge of racing. He had directed The Outlaw Brothers (1988), an even mix of car racing and martial arts fight scenes, which Jackie Chan assisted on as a favor. Although he was a director himself (he codirected Armour of God II), Frankie Chan was known more for being a composer, writing music for Young Master and Winners & Sinners. With Sammo Hung to direct the action sequences, it would seem that Thunderbolt would have a major flow problem. Shooting in Hong Kong, Japan, and Malaysia, producer Chua Lam coordinated all three directors and their various tasks. In the end, however, Gordon Chan’s directing style completely lost out to the other talents involved. A similar occurrence happened with Gordon Chan’s Fist of Legend, where action director Yuen Woo-ping virtually turned it into his movie.

Once the story was changed from its original conception, it became the dumbest plotline ever to be used in a Jackie Chan film. The corny story has to do with a murderous race car driver named Cougar who decides to go to Hong Kong to stir up trouble. While his original intentions are never revealed (a scene that supposedly takes place in Los Angeles gives the only clue to his crimes), this Aussie racer just burns rubber around the streets of Hong Kong, eventually catching the attention of the local police.

To assist them, the police hire a group of professional racing mechanics, one of them being Chan, to capture the speedster at his own game. When Chan traps him, Cougar vows to take revenge by racing him in Japan, noting his skills as a race car driver(?)! After Chan declines, Cougar tries to persuade him to race by fighting him at his garage, but this just leads to Chan lying to the police to seal Cougar’s apprehension. After a bloody escape, Cougar and his men literally turn Chan’s world upside down by lifting his home—a train car—with a crane and dropping it, injuring his father. Cougar’s men then kidnap his sisters in the process. In secret, an infuriated Chan and his crew leave for Japan to race Cougar and save his sisters.

Rumble in the Bronx had its problems with bad guys without agendas, but Thunderbolt’s conflict was so ludicrous that even a straight-to-video movie would have more originality. Jackie Chan’s character becomes the strong silent type, a humble working man who was once a great race car driver but just wants to be another mechanic working with his family. The film showed promise by bringing in Hong Kong star Anita Yuen as a roving reporter out to make Chan a local hero. She is curious about Chan’s nature, and it looked like the two would fall for each other. Nothing really happens, though, except for the repeated lines of dialogue concerning his lack of interest in being interviewed.

Instead of Chan always being on the defensive, as in Tong’s films, Chan becomes the aggressor in Thunderbolt, a key element to making Sammo Hung’s two fight sequences even more gratifying. While an amazing fight sequence in a Japanese pachinko parlor reminds viewers of the good ol’ days of Dragons Forever, the fifteen-minute car chase at the end of Thunderbolt was supposed to be the real action. As it turned out, it looks more like Hal Needham on acid; the scenes are so under-cranked that the intensity and stuntwork look even more cartoonish than one of Chan’s fight sequences. Chua Lam explains why this was done: “If you go to Japan to shoot, you’ll know why things cost so much. After shooting there for a few weeks, there were so many injuries and costs ran so high that we had to move to Malaysia to finish the scene. In slowing down the cars, we could shoot everything just once, and then speed it up for the finished product.” The finale does provide some great stunt work, especially a shot where a car crashes through a lookout tower, but the film is so sped up that it detracts from the serious effort put into the scene. Some of the footage had to have been shot at less than twenty frames per second compared to twenty four!

If one isn’t expecting too much, at least Thunderbolt looks better than many of Chan’s other films in terms of style, and there are some stunning visuals. In keeping with Tong’s synch-sound efforts, the film was shot mostly in Cantonese, but at least 10% was shot in English and another 5% in Japanese. Sammo Hung’s two fight sequences are mesmerizing to watch, although many viewers complained that his varied filmmaking techniques were too much on the eyes.

Due to Chan’s injury in Rumble in the Bronx and the rushed production of the film, much of Chan’s fight action was doubled out by Hung protégé Chin Kar-lok, who has been dubbed “Jackie Junior.” Chin is an amazing stuntman, martial artist, and actor in his own right, most recently praised with a nomination for a film on motorcycle racing entitled Full Throttle. Though Hung can usually mask doubles fairly well, there were just too many behind shots giving the double away. Chan does pull off some of the stunts himself, but he was resting up for First Strike, where he used a double only a few times during the snowboard sequence.

Jackie Chan explains why control means so much to him and why he still gives the original director credit on the marquee: “Because I’m chairman of the Director’s Guild, I can’t say, ‘You’re out—Jackie Chan direct!’ I think that’s not fair. I still put their names in because you have to know the person, and many times I don’t have time to know the director. For some directors, everything is just business. You sign the contract, you get the money. They don’t care.

“I care about the movie. . . . When I go see the rushes and say, ‘What the hell is that? Rubbish!’ they just continue to do these types of things. If they get fired, it’s okay. For me, I make movies for my audience and for myself.” The reason for this is that aside from everything else, Chan wants each film to be just as special as the one before it. He does not believe in giving the audience only half of what a Jackie Chan film can be, just for the sake of making a quick buck.

Believe it or not, Chan has denounced all of the films discussed in this chapter, including Drunken Master II (although he shows some ambivalence). For obvious reasons, he absolutely hated City Hunter, Twin Dragons, and Thunderbolt. In watching these aborted children of his, one does get to see the range that Jackie Chan has as an actor. From excruciatingly goofy to somberly aggressive, however, these characters embody the traits unbefitting his own genre. Whether he will experiment even more with other Hong Kong directors remains a mystery, but these characterizations are duly noted as personas that weren’t meant to be.

1 The Japanese version of City Hunter has a different opening credit sequence featuring more of the comic book intercut with shots of the three actresses. The Japanese laser disc also has four additional minutes of out-takes set to music.

1 The screenwriter must have been more upset than Wong: he was the real-life police officer that Chan was portraying.