Leslie Stephen described Whymper as the Robespierre of mountaineering: ‘he was clearly the most advanced, and would, but for one melancholy tragedy, have been the most triumphant of us all’.1 The tragedy to which he referred had its roots in a series of tiny mistakes, insignificant on their own but culminating in a disaster that shook the Alpine fraternity to its foundations. It stemmed from Whymper’s decision to make 1865 the year in which he conquered the Matterhorn.

Whymper’s first mistake was not to ensure he had a good guide when he wanted one. In 1864 he had verbally engaged Croz for an attempt at the Matterhorn in July the following year. He had neglected to put this in writing and when he did so, in April 1865, Croz was already engaged at Chamonix from 27 June. His employer was John Birkbeck, an Englishman who had won fame a few years previously when he slid more than 1,000 feet down an ice slope, flaying the skin from his back and legs and nearly killing himself in the process. Birkbeck’s plan was to climb Mont Blanc and then to proceed to the Matterhorn. When Whymper arrived in Switzerland in mid-June, he therefore had Croz’s services for barely ten days. He made the most of them.

Accompanied by Croz, Aimer and another guide, Franz Biener, Whymper embarked on an orgy of mountaineering. The Ebenefluhjoch eluded him on 13 June, but the Grand Cornier fell on the 16th - ‘an awful piece of work’2 - the south-west face of the Dent Blanche on the 17th, and the Col d’Hérens on the 19th - almost as bad as the Écrins. On 20 June he crossed the Théodule Pass from Zermatt to Breuil and on the 21st he went up the Matterhorn by a new route: a gully leading to the Furggen ridge, separating the south and east faces. It was an odd choice - Whymper knew very well that the Matterhorn shed more stones than most mountains, and that gullies were natural conduits for stones. The guides were rebellious: they were tired, they were equally aware of the dangers, and Croz for one was certain that the Matterhorn was unclimbable from any direction, let alone via this unpleasant gully. The only person to have implicit faith in Whymper’s decision was Luc Meynet, who had once again been hired as a porter. Whymper quelled their doubts, but was soon defeated by the absurdity of his own decision. At 10.00 a.m., while they were eating lunch, a ferocious stonefall swept the gully, forcing them to abandon their knapsacks and run for cover. Whymper insisted that it was still possible to climb up the gully’s edges, but only Meynet was willing to follow. ‘Come down, come down,’ shouted Croz, scrambling after them. ‘It is useless.’3 One hundred feet below, Aimer sat on a rock, his head in his hands. Biener was out of sight, not having bothered to move an inch. Whymper conceded with ill grace, but refused to give up just yet. His second plan was to cross the Furggjoch and have a stab at the supposedly impossible north-east ridge. This time the guides refused outright: Biener said it could not be done; Aimer asked ‘Why don’t you try to go up a mountain which can be ascended?’4; and Whymper recorded that ‘I then had a small wrangle with Croz in which he came out bumptious.’5 The question of whose will would prevail became academic when, in mid-argument, snow started to fall. They had now no option but to retreat.

Whymper had, in fact, been perfectly sensible in advocating an ascent of the north-east ridge, and had the weather been kinder they might have conquered the Matterhorn the next day. Compared with the snow slopes and rugged ridges that led from Breuil, the north face seemed steep, smooth and unclimbable. Yet Whymper had noticed one or two new facts: on the Italian side the rock formations dipped outwards, therefore it was likely that on the Swiss side they dipped inwards and might prove climbable; further, he had observed how patches of snow clung permanently to the face even on the hottest summer’s day, indicating that the angle was unlikely to be more than 45°; and, when one climbed above the Zmutt Glacier, as he had done, the face looked much shallower than it did from below.

The idea had been mooted as early as 1858, when a contributor to the Illustrated London News had declared: ‘If ever this vast crag is climbed by Hudson, Kennedy or other brave hand, it will be from the Zermatt side; but it will require a perfectly calm day.’6 This had been echoed by the Parker brothers in 1860, who had climbed to a height of 12,000 feet from Zermatt, and were driven back only by bad weather and lack of time. But Whymper had been loath to attempt the north-east face until all the other, simpler-seeming options had been exhausted. Only the snow and his guides prevented him from trying it now. Still, he consoled himself, there would be better weather and maybe better guides - Carrel, for instance - later in the season.

Disconsolately, he trudged with Croz over the passes to Chamonix. Along the way he climbed Mont Saxe above Courmayeur and nearly lost his life in an avalanche - ‘the solitary incident of a long day’7 - and then endured a terrible passage of the Col Dolent, in which the party was forced to hack its way down a 1,000-foot slope of ice with a gradient of 50° where ‘one slip would have been finish’.8 In his journal he did not make light of the descent, and with good reason according to his biographer Frank Smythe, himself an eminent mountaineer. ‘To-day,’ wrote Smythe in 1940, ‘the traverse of the Col Dolent ranks as an ice expedition of the first order, and the first traverse in 1865 was one of the finest, perhaps the finest, ice expeditions of that time.’9 It was all the finer given that Whymper’s fingers were still frostbitten from the Dent Blanche.

At Chamonix, Whymper, Aimer and Biener climbed the Aiguille Verte - the first to do so - a peak of great beauty which everyone said was impossible and which stuck in Whymper’s mind mainly on account of his porter. Instructed to wait on the glacier at the bottom with their provisions, the man had got fed up. He knew very well that the Aiguille could not be climbed and that his employers were dead. So he ate the food. When Whymper came down, famished, there remained nothing but a crust of bread. Whymper loaded him with all the baggage he could muster and drove him viciously across the ice. ‘He streamed with perspiration,’ he wrote with satisfaction. ‘The mutton and cheese oozed out in big drops - he larded the glacier.’10 The porter was soon avenged, however. When Whymper reached Chamonix the local guides were incensed that the Aiguille should have been climbed without their assistance and harassed Whymper’s men remorselessly. They did not believe that it had been done: ‘They were liars, yes, liars, they had not climbed the Aiguille Verte.’11 When Aimer and Biener complained to Whymper he sent them back out to meet the mob, and strolled after them to watch the fun. A small riot began, which was only ended by the intervention of the police and a fellow Alpine Clubber, T. S. Kennedy, who confronted the ringleader and ‘thrust back his absurdities in his teeth’.12 Whymper was too tired to contribute to the scene. ‘These days are mixed up in my head in an inextricable jumble,’ he wrote in his diary. ‘I know that I had my watch mended, my hair cut and that innumerable people talked endless rubbish to me. I know that the weather was abominable and that I was very like the weather. The first day was almost entirely occupied by the Verte row. The second partly so. I was waited on by the Commissary of Police.’13

On 3 July, while Chamonix was still in a state of unrest, he crossed the Col de Talèfre - again, it was a first - and on 6 July he climbed the Ruinette - another first - where, amidst fields of unending snow and rock, he at last felt free from the pressures of Chamonix. He then made the first passage of the Portons Pass to the Otemma Glacier, crossed the Col d’Oren and then the Col de Valvournera to the Val Tournanche and Breuil. All the time he was heading towards his ultimate goal. ‘Anything but the Matterhorn, dear sir!’ wept Aimer, when he realised what was happening, ‘anything but the Matterhorn.’14 Fortunately for Aimer, he was not needed on the dreaded mountain. Jean-Antoine Carrel had just returned from an unsuccessful attempt on the Italian ridge and Whymper was able to persuade him to have a stab at the other side on 9 July, camping first on the Col Théodule, with the proviso - insisted upon by Carrel - that in the event of a failure they would try once again the Italian ridge. Whymper paid off Aimer and Biener, ‘with much regret, for no two men ever served me more faithfully or more willingly’,15 and thus ended an eighteen-day marathon during which he had climbed up more than 100,000 feet of mountainside. According to Smythe it was an epic ‘that stands unique in the annals of mountaineering’.16

In Alpine literature Whymper comes across as a species of superman, a climbing machine for whom height and hardship were nothing. Now and then, however, from journals and archives one gets a glimpse of his weaker, human side: betting Moore two francs that they would not reach the Écrins within thirteen hours; struggling so long to squeeze his feet into ill-fitting boots that his companions almost left him behind; being bedridden for two days after the Écrins, while his fellows continued easily onwards; losing four francs to Moore and Adams-Reilly on a bet that he and they would never climb one mountain; being crippled for a day and a night after climbing another; imploring the guides to stop and wait for him on the Dent Blanche; marvelling at Croz’s anecdotes, around a fire of rhododendron branches. These little snatches are brought to life when one considers Whymper’s age. In the season of 1865 he had only just celebrated his 25th birthday. He was terribly young.

Whymper’s second mistake of that season was to place such implicit trust in Carrel. He had already had some experience of the man’s unreliability. He knew, too, of his proprietorial attitude to the Matterhorn and, in particular, the Italian ridge. What he did not know, however, was the depth of Carrel’s patriotism: Carrel wanted the Matterhorn to be conquered by an Italian, led by an Italian guide (himself), via the Italian ridge. Although willing to go with Whymper on 9 July, Carrel had already accepted an offer for 11 July from a man who was much more to his liking. Felice Giordano was an engineer and geologist who, in concert with Italy’s Finance Minister, Quintino Sella, had determined to take the Matterhorn by stealth. On 7 July Giordano was ready to make his move, and wrote to his sponsor from Turin: ‘Let us, then, set out to attack this Devil’s mountain, and let us see that we succeed, if only Whymper has not been beforehand with us.’17

On 8 July, as Whymper was preparing for the following day’s climb, news arrived that an Englishman was ill at Val Tournanche. He felt honour-bound to help him, so set aside his preparations and walked off to get medicine. This was his third mistake inasmuch as, that although it was the decent thing to do, it meant delaying his climb. While engaged in his third mistake, Whymper became aware of the extent of his second. En route to Val Tournanche he met the two Carrels leading an Italian gentleman towards Breuil - only in the capacity of porters, they assured him. Suspiciously, he reminded them of their agreement. Ah yes, Jean-Antoine Carrel remarked, there was a small problem. They were engaged to travel in the Aosta valley with ‘a family of distinction’18 from 11 July. It was most unfortunate, but there was nothing to be done, the arrangement being of long standing and precise details having been confirmed only that day. Whymper was annoyed but not too worried. The family of distinction was obviously a group of ladies who wanted to potter over the lower glaciers. ‘That work is not for you,’19 he chided, pointing out that he had dismissed two first-rate guides in the expectation of having Carrel’s services for some time. Carrel made no comment, but smiled apologetically to indicate that the matter was out of his hands. Honour applied as much to guides, he implied, as to English milords with stricken countrymen.

Whymper gave the sick man medicine and dragged him back to Breuil, from where he hoped an ascent with Carrel might yet be possible. The weather was too bad on 10 July and worsened on the 11 July, giving Whymper the consolation that even had Carrel been free they could have done nothing - certainly they could not have walked to Zermatt and gone up from there. Meanwhile, Giordano fretted anxiously. ‘I have tried to keep everything secret,’ he wrote to Sella, ‘but that fellow, whose life seems to depend on the Matterhorn, is here, suspiciously prying into everything. I have taken all the competent men away from him, and yet he is so enamoured of this mountain that he may go up with others, and make a scene. He is here, in this hotel, and I try to avoid speaking to him.’20

The Italian conspiracy got off to a flying start. On the morning of 12 July Whymper’s patient - who was the Revd A. Girdlestone, a dubious exponent of guideless climbing - rose early and seeing that the clouds had thinned a bit, woke him with the news that a party had left in the early hours for the Matterhorn. It comprised the two Carrels, several porters and a mule-load of provisions. By strange coincidence it was directed by one of his fellow guests, a man called Giordano -though he, apparently, had not accompanied the party.

Whymper was furious. He had been ‘bamboozled and humbugged’.21 On complaining to the innkeeper he was greeted with a smile like Carrel’s: a conquest from Breuil would make his hotel famous. Whymper snatched a telescope and peered through it. Yes, there was Carrel and his party, making their way up the lower slopes. He returned to his room and paced up and down, smoking cigar after cigar. Carrel had stolen a lead. But his group was large and unwieldy. It would take them three days to reach a position from which they could tackle the summit. If he moved fast Whymper could be in Zermatt inside a day and, conditions willing, could be at the Col Théodule on the next and on the summit the day after. It was just possible. But he had no guide. Aimer and Biener were gone, and Carrel had taken every able-bodied man in Breuil with him. Even Luc Meynet was unavailable, being busy with his cheese-making - or bribed by Carrel as Whymper interpreted it. If, by some chance, a guide did appear there were no porters. Giordano had planned with foresight.

Miraculously, Whymper was saved by the arrival of Lord Francis Douglas, an ‘exceedingly amiable and talented’ 18-year-old whose brother, the Marquess of Queensberry, would later instigate the Wilde trial over which Wills was to preside. Douglas was no stranger to daring exploits: he had scaled the walls of Edinburgh Castle aged 14, and had swum the Hellespont aged 16. Although not an experienced mountaineer he had done some fine climbing that season - Whymper was very impressed by his account of the Ober Gabelhorn, on which he had nearly killed himself - and had in tow young Peter Taugwalder, son of old Peter Taugwalder from Zermatt. Old Peter was a well-known figure, described by one visitor in 1861 thus: ‘hard as nails, brown as a pet meerschaum, about 5ft. 6in., with head and shoulders like a Highland Bull’.22 He and his son had carved themselves a reputation for leading tourists up the easier slopes. They were second-echelon guides - ‘Rather eccentric in his ways,’23 was the entry Old Peter merited in one guidebook - with none of the flair or knowledge of a Croz or an Aimer, and several Alpine Clubbers had been disappointed by their performances on difficult slopes. But they did have some interesting opinions regarding the Matterhorn. Old Peter had reconnoitred the north-east ridge and was convinced, like Whymper, that it was surmountable. Casually, Douglas mentioned that he had hired Old Peter for an attempt.

Whymper was immediately interested. Did Douglas truly want to climb the Matterhorn? Yes. Did he want to do so from Zermatt? Yes. Could young Taugwalder carry their gear there? Yes. Then Whymper would be very happy to join them, and could they leave as soon as possible? Douglas agreed - or, as Whymper put it, ‘it was determined he should take part in my expedition’24 - and the next day he and Douglas crossed the Théodule and went down to Zermatt where they instructed old Peter Taugwalder to prepare for an immediate attack on the Matterhorn.

Then Croz turned up. Birkbeck had fallen ill in Geneva, so he had allied himself to the Revd Charles Hudson and his protégé Douglas Hadow. Hudson too was planning to climb the Matterhorn and was staying at the same hotel as Whymper - the Monte Rosa. That evening, while Whymper was finishing his dinner, Hudson strode in from a reconnaissance. Whymper sized him up, and then took him aside. They talked for a while and decided that it would be wasteful for two separate teams to go up the Matterhorn. It would be much better if they joined forces. This was Whymper’s fourth mistake.

Hudson, vicar of Skillington in Lincolnshire, was the glamourous face of British mountaineering. Unlike many of his fellows who were not only odd but, to be frank, looked odd, Hudson was a handsome, cheerful man without a problem in the world. Young women stuck his photograph in their albums, from where it smiled out romantically above a dashing signature. No other man seemed so about to give a wink as Hudson. At the same time - and this doubtless contributed to his charm - he was entirely self-effacing. ‘He would have been overlooked in a crowd,’ Whymper wrote, ‘and although he had done the greatest mountaineering feats which have been done, he was the last to speak of his own doings.’25 Leslie Stephen described him as ‘the strongest and most active mountaineer I ever met’.26 Others said he was as skilful as a guide. He had incredible stamina, considering a 50-mile hike a fair day’s exercise - Whymper thought 30 miles was reasonable - and he had been known to walk from St Gervais near Chamonix to Geneva and back, a distance of 86 miles, within twenty-four hours. He had been climbing in the Alps since 1853, had made with Kennedy the first guideless ascent of Mont Blanc by a new route in 1855 and was, in short, the best companion Whymper could have asked for.

Hadow was a different proposition altogether. He was 19 years old and, as Whymper tactfully put it, ‘had the looks and manners of a greater age’.27 It was his first season in the Alps and although he was a rapid walker he had spent very little time in the Alps. Whymper quizzed Hudson about him and received the answer that Hadow ‘has done Mont Blanc in less time than most men’.28 Hudson then mentioned a number of other exploits and concluded that ‘I consider he is a sufficiently good man to go with us.’29 Here, Hudson was being generous. Hadow was young, inexperienced and exhausted. But what else could Hudson say, in the circumstances? He had taken Hadow on, had planned to climb the Matterhorn with him, and it would have been churlish to drop him for no reason other than he did not suit the new situation.*

Whymper’s fourth mistake was therefore not only to combine the two parties into one - whatever the merits of the individuals, small, agile groups are more effective than large ones - but to include Hadow in the party. In such a large expedition, the largest ever to attack the Matterhorn, the group was dependent on its weakest member. If they were all roped together and one man fell on a treacherous slope he might drag one, then two and, as the weight increased, the whole party in his wake. Hadow was indisputably the weakest member. He had visited Birkbeck the previous summer at his home in Settle, where he had been taken up a nearby hill and had displayed unfortunate incompetence. ‘On one side there is a small piece of rock which has to be descended with care,’ wrote Mrs Birkbeck. ‘but most of our party could walk down it with ease. Poor Mr. Hadow found it very difficult and had to be helped down.’ Mrs Birkbeck opined that if Birkbeck had not been taken ill in Geneva and had continued to Zermatt with Croz and Hudson, ‘Mr. Hadow would not have been of the party; he was no mountaineer.30

On Thursday, 13 July, Hudson wrote a quick note to a friend, the Revd Joseph McCormick, who had planned to join him and Hadow for the Matterhorn but had been delayed.

MONTE ROSA HOTEL, Thursday, 5 a.m.

MY DEAR M’C,

We and Whymper are just off to try the Cervin [the French name for the Matterhorn]. You can hear about our movements from the landlord of the Monte Rosa Hotel. Follow us, if you like. We expect to sleep out tonight, and to make the attempt to-morrow … We expect to be back to-morrow. It is possible we might be out a second night, but not likely. Ever yours affectionately, C. HUDSON31

Hudson might have been a surgeon reassuring a patient: a short while and it will all be over.

He and Whymper pranced up the Matterhorn. It was so much easier than they had expected that they led the way, taking it in turns to hack steps in the ice while the guides hung behind. When they made camp on a ledge at 11,000 feet they were almost delirious. Compared to the Italian route, the north-east ridge, which appeared so daunting from below, was simplicity itself. Croz and young Peter Taugwalder scouted ahead and returned with the news that there ‘was not a difficulty, not a single difficulty! We could have gone to the summit and returned to-day easily!’32 Everybody went to bed in good spirits. ‘Long after dusk,’ Whymper wrote, ‘the cliffs above echoed with our laughter and with the songs of our guides, for we were happy that night in camp, and feared no evil.’33 He and the Taugwalders slept in the tent and the others made do as best they could outside. (Privately, Whymper noted that the Taugwalders snored so badly that he did not get any sleep and wished he had chosen to camp out.) In Breuil, meanwhile, Giordano had heard of Whymper’s movements and though he thought them ridiculous had sent messages to Carrel telling him that he must ‘climb the mountain at all costs, without wasting time, and must make the route practicable’.34

The following day, the rocks were more difficult and Whymper handed the lead to Croz. ‘Now,’ said the Chamonix guide, ‘now for something altogether different.’35 In fact it wasn’t that much different. All Croz had to do was extend an occasional hand to his employers. The rocks were testing in places, and extremely exposed, but Whymper thought it a lot easier than the Pointe des Écrins. He was worried, however, by Hadow, who ‘was not accustomed to this kind of work and required continual assistance’.36 They went up and up, crossing 400 feet horizontally here, ascending 60 feet vertically there, then doubling back to a convenient ridge when their way was blocked. There was an awkward corner and finally they were there, separated from the summit by 200 feet of snow. ‘The last doubt vanished!’ Whymper wrote, ‘The Matterhorn was ours!’37

Or was it? All the way up there had been a succession of alarms in which one or other of the party thought he had seen figures on the summit. It was not impossible that Carrel’s party had beaten them and were already on their way down. Croz and Whymper raced neck and neck up the final stretch and discovered to their delight that no footsteps could be seen in the snow. ‘At 1.40 p.m. the world was at our feet,’ wrote Whymper, ‘and the Matterhorn was conquered.’38

There yet remained a faint possibility that Carrel had got there first: the summit comprised a ridge some 350 feet long, and there was a chance that the Italians had left traces elsewhere. Whymper ran along the ridge. Again nothing. Peering over the edge, he saw his rivals some 1,250 feet below, crawling like ants up the hillside. He and Croz yelled and waved their arms, to no apparent effect. ‘We must make them hear us; they shall hear us,’39 Whymper cried. He seized a block of stone and hurled it down. Croz joined him and together they wrestled lumps of crag down the cliff. ‘There was no doubt about it this time,’ Whymper crowed. ‘The Italians turned and fled.’40

Then came the flag-planting. One of the tent poles had been removed that morning - against Whymper’s protestation that they were tempting providence - and it was now embedded on the northern end of the ridge with Croz’s shirt tied to it as a flag. The day was superlatively calm and clear, and they marvelled at a view which read like a roll-call of Alpine exploration. ‘All were revealed,’ Whymper wrote:

[N]ot one of the principal peaks of the Alps were hidden. I see them clearly now - the great inner circles of giants, backed by the ranges, chains and massifs. First came the Dent Blanche, hoary and grand; the Gabelhorn and pointed Rothorn; and then the peerless Weisshorn; the towering Mischabelhorn, flanked by the Allaleinhorn, Strahlhorn and Rimpfischhorn; then Monte Rosa - with its many Spitzes - the Lyskamm and the Breithorn. Behind were the Bernese Oberland, governed by the Finsteraarhorn; the Simplon and St. Gotthard groups; the Disgrazia and the Orteler. Towards the south we looked down to Chivasso on the plain of Piedmont, and far beyond. The Viso - one hundred miles away - seemed close upon us; the Maritime Alps - one hundred and thirty miles distant - were free from haze. Then came my first love - the Pelvoux; the Écrins and the Meije; the clusters of the Graians; and lastly, in the west, gorgeous in the full sunlight, rose the monarch of all - Mont Blanc. Ten thousand feet below us were the green fields of Zermatt, dotted with chalets, from which blue smoke rose lazily. Eight thousand feet below, on the other side, were the pastures of Breuil. There were forests black and gloomy, and meadows bright and lively; bounding waterfalls and tranquil lakes; fertile lands and savage wastes; sunny plains and frigid plateaux. There were the most rugged forms, and the most graceful outlines - bold, perpendicular cliffs, and gentle, undulating slopes; rocky mountains and snowy mountains, sombre and solemn, or glittering and white, with walls - turrets - pinnacles - pyramids - domes - cones - and spires! There was every combination that the world can give, and every contrast that the heart could desire.41

Such a sight might be visible one day in a hundred, Whymper reckoned. They stared at it for a long hour before starting on the descent.

The flag they left behind was not an impressive thing; nor was there any wind to make it float; but it was visible from all directions. Down in Breuil, convinced that their group had succeeded, the inhabitants came out en fête, toasting Carrel, Italy and the Matterhorn. It was only when the dejected team arrived home that they learned their mistake. ‘It is true,’ said the men. ‘We saw them ourselves - they hurled stones at us! The old traditions are true - there are spirits on the top of the Matterhorn!’42

Storm on the Matterhorn, 1862

(© ROYAL GEOGRAPHICAL SOCIETY, LONDON)

Albert Smith

(BY COURTESY OF THE NATIONAL PORTRAIT GALLERY, LONDON)

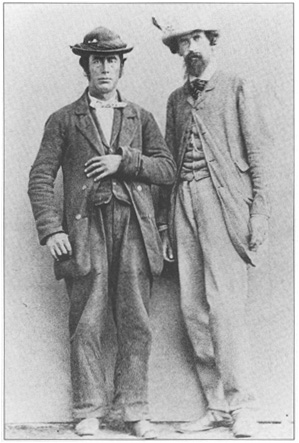

Leslie Stephen (right) with Melchior Anderegg

(© THE ALPINE CLUB COLLECTION, LONDON)

John Tyndall

(BY COURTESY OF THE NATIONAL PORTRAIT GALLERY, LONDON)

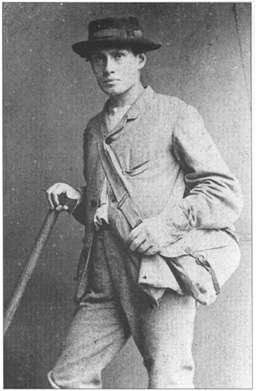

Edward Whymper, 1865

(© THE ALPINE CLUB COLLECTION, LONDON)

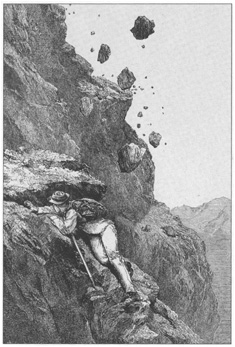

Almer’s leap

(© ROYAL GEOGRAPHICAL SOCIETY, LONDON)

Whymper on the Matterhorn

(© ROYAL GEOGRAPHICAL SOCIETY, LONDON)

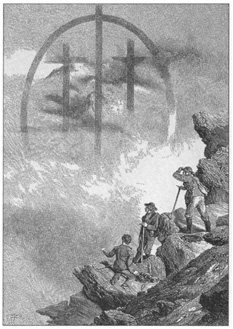

The apparition which followed the Matterhorn disaster

(© ROYAL GEOGRAPHICAL SOCIETY, LONDON)

Whymper’s companions on the Matterhorn ascent, 1865

(© THE ALPINE CLUB COLLECTION, LONDON)

Sir Edward Davidson (centre) with guides

(© THE ALPINE CLUB COLLECTION, LONDON)

William Coolidge

(© THE ALPINE CLUB COLLECTION, LONDON)

Edward Whymper in old age

(© THE ALPINE CLUB COLLECTION, LONDON)