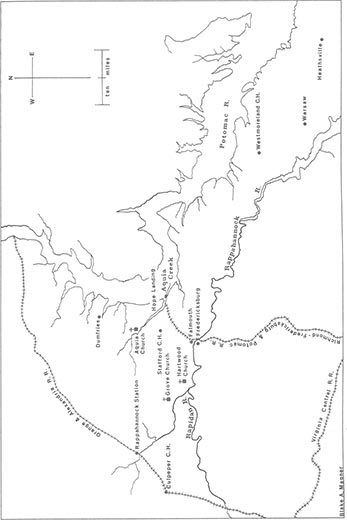

Theater of Operations, February–March 1863.

Chapter 2

A RESTLESS WINTER

The Battle of Hartwood Church

The men of the Cavalry Corps did not idle the winter of 1862–63 away with drilling and book learning. Consistent with Hooker’s more aggressive approach, the men regularly took the field, raiding and picketing. They spent the winter balancing training and education with hard and active service. The men typically spent ten days out on the picket line and then the next ten days in camp. “It is rather tough, but I guess we can stand it,” observed a member of the 1st Pennsylvania Cavalry.1 A member of the 16th Pennsylvania Cavalry echoed a similar note. “I like soldiering very well yet it is hard,” recounted Sergeant Henry W. Owen. “We are exposed to all kinds of weather, to all climates, are called up at all times of night and some times in case of a raid, we march all day and stand by or sit on our horses all night or nights as the case may be.”2 The Yankee horsemen picketed the Rappahannock River from Falmouth to Hartwood Church in Stafford County. They also patrolled the countryside, picketed both flanks from Fredericksburg to Hartwood Church, and guarded the Richmond, Fredericksburg, & Potomac Railroad (RF&P) to Aquia Landing. Averell’s division picketed along the RF&P near Potomac Creek, Gregg’s division handled the left near Belle Plain, and Pleasonton’s division remained flexible, filling in where needed.

Hartwood Church marked the far-right flank of the Army of the Potomac’s position. Located about four miles north of the Rappahannock River and eight miles west of Falmouth, the church sat at the junction of the Warrenton (or Telegraph) Road and the Ridge Road and provided a conspicuous landmark in the densely wooded countryside. In 1825, the Winchester Presbytery organized the Yellow Chapel Church in Hartwood, using a small eighteenth-century frame structure that had been an Anglican chapel. In 1858, at the cost of $2,000, a handsome red brick sanctuary was built and renamed Hartwood Church. Both sides, drawn by its location on commanding high ground, had used its grounds for camps, and most of the interior woodwork of the church had been used for firewood during the bitter Virginia winters, leaving the sanctuary barren and the church useless for worship during the war.3 The church sat on a divide between streams running south into the Rappahannock River and east into the Potomac River. In the winter of 1862–63, Union outposts dotted the area, and both infantrymen and horse soldiers occupied the church grounds.

Theater of Operations, February–March 1863.

The Federal picket lines in the vicinity of Hartwood Church covered nearly eight miles along the north bank of the Rappahannock. Northern saddle soldiers manned the area heavily, spending several days on duty for every day in camp. An officer of the 4th Pennsylvania Cavalry, whose company pulled regular picket duty at Hartwood Church, noted that his unit “had to scout the country in the vicinity of our forces, in order to guard against raids and surprises by any large body of the enemy.”4

Picket duty was miserable, numbing work that required the men to remain mounted in the face of howling winds and stinging precipitation. When not on actual picket duty, the men had to remain ready to mount up and move at a moment’s notice. They were not permitted to sleep while on picket.5 The line ran along the banks of the Rappahannock, crossing the Northern Neck and running past Hartwood Church. The picketing at the ends of the line tended to be more arduous because the vedettes were often exposed to guerrilla attacks or raids by roving bands of Southern cavalry.

Sergeant Nathan Webb of the 1st Maine Cavalry reflected on the misery of picketing in his diary. After a heavy storm of snow and sleet in January 1863, Webb observed, “The snow was blowing, the wind howling, and we were all hovering over our little fires and not in a very admiring mood of Army life. We failed to see the romance of it, and thought it tough amusement, ‘this camping on old Virginia’s soil beneath the good skies and under the rustling trees, etc.’” The freezing, miserable Yankees longed for warm meals and cozy family hearths.6

The enterprising pickets fraternized with their counterparts on the opposite banks of the river. “The rebs on the opposite bank are shivering around their picket fires peaceably disposed fellows they are and very talkative,” noted a Hoosier horse soldier.7 An informal cartel developed wherein the pickets traded coffee for tobacco and sent newspapers back and forth. Men floated little rafts across the river to facilitate their illegal trading. Good-natured taunts flew across the water along with the goods being bartered. “Picketing in good weather was real pleasure during this state of affairs,” observed the regimental historian of the 1st Maine Cavalry, “but matters got to such a pass that it was found necessary to order all communication between the pickets stopped. This order was pretty well obeyed, but occasionally the temptation was too strong to be resisted, and trade was carried on in a small way on the sly.”8 An officer of the 2nd New York Cavalry recalled, “Squads of soldiers from both armies may be observed seated together on either side of Rappahannock earnestly discussing the great questions of the day.…During these interviews, trading was the order of the day.…There was…a special demand of the Rebels for pocket knives and canteens.”9

However, as an officer of the 1st Rhode Island Cavalry pointed out, “Our pickets are the eyes of the army,” he wrote. “If they sleep, or are negligent of duty, the whole army is in danger. The neglect of a single duty on picket is liable to the severest punishment. The officers in command of the pickets hold most important and responsible positions, having, as it were, the keys to the gates which separate the two contending armies.”

Each brigade patrolled a specific section of the picket line, with proportional guard details selected from each regiment of the brigade. These details were divided into small bodies for reliefs and reserves. The reserves typically established their headquarters deep in the nearby woods, hollows, or other concealed places, “where fires are allowed, the men remaining dismounted with the privilege of keeping themselves as comfortable as possible, but always keeping themselves girded for an attack. The horses are kept saddled and bridled, hitched to the nearest trees, that the men may instantly spring to the defensive should the men on their posts give an alarm, or be driven in.”

Where a regiment had three battalions, one stood picket and one remained in reserve each day of their three-day tours of duty. They would stand picket, on horseback, with their horses’ heads facing in the direction of the enemy, with carbine advanced, for two to four hours at a time, until the corporal of the guard relieved them. They stayed vigilant, their revolvers and carbines at hand and ready to be fired instantly. Pickets challenged anyone approaching their positions, and they raised the alarm by firing if the right countersign was not given. Officers regularly visited the picket posts to inspect and encourage them and to make certain that all was well along the line. Once relieved, they could then eat and rest, often by a fire, but could not remove their side arms. “Everything is so systematically arranged that, in case of an attack, we could give the rebels a warm reception, holding any force at bay until we could be reinforced from the main army.”10 Picketing, while tedious, was not easy duty in the frigid Virginia winter.

On February 5, a detachment of Duffié’s brigade of Averell’s division marched up the north bank of the Rappahannock River to burn an important railroad bridge at Rappahannock Station, thirty miles above Falmouth. Major Samuel E. Chamberlain of the 1st Massachusetts Cavalry commanded the expedition. The bridge that carried the Orange & Alexandria Railroad across the river had recently been rebuilt by the Confederates and was a strategic position. A strong detachment of Confederates guarded the sturdy wooden trestle. The Yankee raiders contended with terrible roads made into sheets of ice by the combination of snow and freezing rain. They carried three days’ worth of rations for the men and one day of forage for their horses. On the first night, the Federals camped in a pine grove near Grove Church. They built rail fence fires to cook their dinners and had a pleasant evening until the snow turned to rain. After putting out pickets, “we stood around our fires or sat, making ourselves as comfortable as circumstances would permit. I slept none that night, but ate considerable, the long and tedious march giving us good appetites,” reported bugler Henry T. Bartlett of the 1st Massachusetts Cavalry.11

The next morning, the Federals called in their soggy pickets and resumed the march. That afternoon, the dim winter sun broke through for a few hours of blessed relief. “We continued our course through the woods & valley and across runs of water where your feet would be covered by water if they remained in the stirrups.” At midnight, they halted in a thick wood about a mile from the bridge and established a bivouac. No fires were allowed, and the men stood ankle deep in frigid slush until 4:00 a.m., when they finally received permission to lie down. The soaked horse soldiers shivered under their blankets, trying to fend off the winter chill that permeated their bones.12

While most of his command struggled to stay warm, Chamberlain detailed men with axes and carbines to approach the bridge. “Not three strokes of axe was given, when the sentry at the other end of the bridge fired into the workmen and alarmed the village and troops encamped near there.” The alarm spread quickly, and the surprised Rebels scrambled to respond. “Our batteries were planted on the brow of the hill by the light of the moon and the firing of the Rebs, our men kept on working disregarding the shot which came thick & fast around them and did not leave until they had accomplished their object of making the railroad bridge one of destruction, another party tore up the track for some distance and tore down the wires and poles of their telegraph for some three miles.”13

Amazingly, the roads had deteriorated further, making the return march even more arduous. “The water in the holes and ruts was frozen up, so as to make it very slippery along like a boy trying to use a pair of stilts on ice.” Bartlett’s horse fell twice, causing the bugler to crash to the icy ground in an undignified heap. Major Chamberlain allowed the men of his column to stop and build fires to warm themselves a bit, and the march resumed the next morning, with the weary horsemen arriving back at camp that afternoon.14 “Splendid affair, I assure you the ‘Rebs’ were so mad about it…the enemy would fire at our men,” recounted Captain Walter S. Newhall of the 3rd Pennsylvania Cavalry.15 The Northern horse soldiers returned after taking only two casualties in a severe firefight and a long march through terrible conditions.16 “I got in night before last from a 3 days scout and a more uncomfortable 3 days and nights I never passed,” reported Corporal John B. Weston of the 1st Massachusetts. “I was in the saddle 20 hours out of 24.”17

The combination of picketing, reconnaissances, and raids took its toll on men and animals. “Our regiment has been worked very hard all winter doing picket duty and our horses are in poor condition,” recounted Captain Bliss, “but we now have plenty of forage and hope soon to have less work so that we can get up our war horses a little.”18 “The infantry lose more men by the casualties of battle, but the cavalry nearly make it up in excessive duty and exposure,” observed an officer of the 1st Pennsylvania Cavalry.19

Horses, for all of their size and strength, are fragile beasts. They require a great deal of care and constant attention. They also suffered in the winter cold, perhaps more than the men. “I…dare not go and look at my horses,” observed Captain Adams in late January. “I know just how they look, as they huddle together at the picket-ropes and turn their shivering croups to this pelting northeaster. There they stand without shelter, fetlock deep in slush and mud, without a blanket among them, and there they must stand—poor beasts—and all I can do for them is to give them all the food I can, and that little enough. Of oats there is a sufficiency and the horses have twelve quarts a day; but hay is scant, and it is only by luck that we have a few bales just now when we most need them.” Adams fed his animals four times per day, “and if they have enough to eat, they do wonderfully well, but it comes hard on them to have to sustain hunger, as well as cold and wet. It is all over, however, with any horse that begins to fail, for after a few days, he either dies at the rope, or else glanders set in and he is led out and shot. I lose in this way two or three horses a week.”20 Sergeant Nathan Webb of the 1st Maine Cavalry noted that the morning after a heavy January snowstorm, “the horses have icicles pending from and snow frozen over them. I took pains last night to cover up Hal with one of my blankets and he is not now shivering like most of the others.”21

“We are still living in our shelter tents, or I might rather say—we live out doors and sleep in our tents for they are not large enough to live in,” observed Captain Delos Northway of the 6th Ohio Cavalry. “They are just high enough so that we can creep in and sit up, that is if we sit on the ground. But they are famous things to sleep under for at night we can be snug as kittens.” Northway noted that his regiment had occupied its winter camp at Dumfries for nearly a month. “When we came, we were informed that it was only for temporary duty and so we left baggage and everything else nearly, at Stafford,” he noted. After four weeks of hard duty, he and his men grew ragged, as they had only the clothes on their backs. “Mort hasn’t changed his clothes for four weeks,” he sniffed, “and my pants could be very fitly described by the military command ‘To the rear open door.’” In spite of the adverse circumstances, Northway and his command vowed to make the best of the situation. “We live well, have plenty of soft bread, coffee, pork, beans, potatoes, molasses, sugar, can buy fresh oysters for seventy five cents per bushel and on the whole have lots of things for which to be thankful.”22

Sergeant William H. Redman of the 12th Illinois Cavalry echoed a similar note. “We have our tent fixed quite comfortable to live,” he reported to his sisters. “We have a nice fire place to cook by and we have raised our tent about three feet so that we have plenty of room. We call the whole arrangement ‘our shebang.’ You would laugh to see how we live,” he concluded.23

On February 17, an expedition to break up smuggling on the peninsula between the Rappahannock and Potomac Rivers set off. The expedition consisted of two squadrons of the 8th New York Cavalry and of the 2nd Wisconsin Infantry. Captain Craig Wadsworth, of Major General John F. Reynolds’s staff, led this expedition. The New York horsemen visited Westmoreland Court House, Warsaw, Union, the Hague, and Heathsville and covered nearly 150 miles in five days, bringing back twelve prisoners, including a Confederate signal officer, a lieutenant, several smugglers, a quantity of contraband goods, four Rebel mails, and a large quantity of bacon. The raiders also destroyed “a large quantity of whiskey intended for rebel consumption.”24

The Northern horse soldiers left a swath of destruction in their wake. The 9th New York camped near Aquia Church. The church dated to 1751 and had survived the Revolutionary War. It was a handsome place, built in the shape of a cross. “The walls are badly defaced by soldiers, as everyone seems to think that it is necessary to write his name wherever there is a good place for it. The floor which is stone has also been torn up in several places, and even those which mark the resting place of the dead are not left undisturbed,” observed a member of the 9th New York in February. “It is a sad sight to see the desolation which marks the track of the Union army,” he continued. “Nothing escapes where the men are allowed to roam around unchecked. The finest houses are soon reduced to a pile of ruins and as for fences they disappear as if by magic as soon as a lot of soldiers camp near them.”25

On February 21, three squadrons of the 8th New York Cavalry went out on picket duty near Dumfries. They occupied a desolate stand of scrub oak and pine trees that offered little shelter from the bitter cold. It snowed all night and most of the next day, accumulating nearly an additional foot of fresh snow. “If a horse moved two feet to the right or left, he would go in so deep that it was impossible to save him from strangling,” recorded Private Jasper Cheney in his diary.26 Several men had their boots freeze to their feet, meaning that they had to be cut away in order to remove them. Henry Norton recalled, “It was so cold one night when I was on picket, that I got off from my horse and walked around to keep my feet from freezing.” Norton had received orders not to dismount, but he “thought if the rebels had as hard a time to keep warm as I did, they would not trouble us any.” The men lit a bonfire and piled up fence rails “to keep us out of the snow, and we would roast one side a while, and then turn around and warm the other side.”

As long as it stayed bitter cold, Norton was right. However, once it thawed out a bit a few days later, the Confederates grew bolder. Angry locals, dubbed “bushwhackers” by the Northerners, “would steal up in the daytime and shoot men at their posts.” A number of men were killed and wounded that way, and the activities of the guerrillas and bushwhackers gave the Confederate high command an accurate picture of the dispositions of the Army of the Potomac. They targeted the members of the 8th New York’s three newest companies and captured quite a few of them, gaining all sorts of valuable intelligence from their new prisoners.27

Samuel M. Potter of the 16th Pennsylvania Cavalry spent an enjoyable day on February 21, visiting a friendly family near Fredericksburg. He and his companions spotted activity on the south side of the Rappahannock. “After staying there a short time to get a spyglass we went down to Fredericksburg,” recounted Potter in a letter to his wife. “We got on the river bank opposite the city & could see them playing ball. Could hear them laughing & talking & we saw a number who had blue overcoats on which they took off our dead soldiers.” Potter’s host pointed out the killing fields in front of Marye’s Heights, chilling the inexperienced Pennsylvania soldier.28

On February 22, the Army of the Potomac celebrated George Washington’s birthday with a booming one-hundred-gun artillery salute.29 A heavy snowstorm accompanied by a furious northeast wind amplified the booms of the celebration. Eight inches of fresh snow fell. “Jolly old times in camp this morning,” reported Private Albinus Fell of the 6th Ohio Cavalry, “Our tent was drifted over with snow inside and out. Some of the boys could not get out of their tents until the snow was going away. The boys had to halloo as they hunt around in the snow for wood.”30 Thomas Covert, also of the 6th Ohio, noted, “We had orders to move at eight o’clock this morning but it commenced to snow in the night and the snow was about six inches deep this morning and asnowing like the deuce and has snowed all day, and the snow is over a foot deep now, and it is about noon now. We cant move today. If we did we would all freeze to death.”31

Other Yankee horsemen waxed philosophic that day. The men of the 3rd Indiana Cavalry picketed around Washington’s boyhood home on the Rappahannock east of Fredericksburg. As they huddled for warmth, talk turned to the brutal winter of 1776 and the ordeal of Valley Forge. “This is Washington’s birthday—and all about the old homestead and above his mother’s grave, the cannon of his contending sons are celebrating its return! Nonsense. Mockery!” proclaimed Samuel Gilpin in his diary. “If the father was a great and good man, let the sons be ashamed of themselves and go home,” he concluded.32

Brigadier General William Woods Averell did not feel well on Washington’s birthday. He suffered from chronic dysentery, which sapped his strength. He spent a quiet day studying Stoneman’s orders for the formation of the Cavalry Corps, trying to find shelter from the howling storm in a smoky tent. The decision to divide his brigade in two and form a division from it surprised Averell.33

Company I of the 6th New York, as well as all of the 8th Pennsylvania, drew picket duty that day. The freezing soldiers slogged through the miserable conditions for fifteen miles, establishing their picket line along Cannon’s Run, near Ebenezer Church. “The suffering and hardship of that march, and later on, the exposure and inactivity while on the lonely picket-post, were such that none but an experienced soldier can fully understand,” observed a New Yorker.34 Colonel Devin, commander of the brigade, used this expedition to identify a suitable site for a bridge over Aquia Creek a mile or so beyond Ebenezer Church.35

The Regulars stood picket duty just like their brethren in the volunteer units. Company F of the 6th U.S. Cavalry picketed along the lower Rappahannock just across the river from the camps of Lieutenant General Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson’s infantry corps. Men stood picket duty for four hours at a time, and it usually took up to two hours to get to and from picket posts, meaning that the men had only two hours to rest, “if such a thing as sleep were possible under the circumstances.” Although they tried to cover themselves with brush, the Regulars suffered along with their volunteer brethren.36

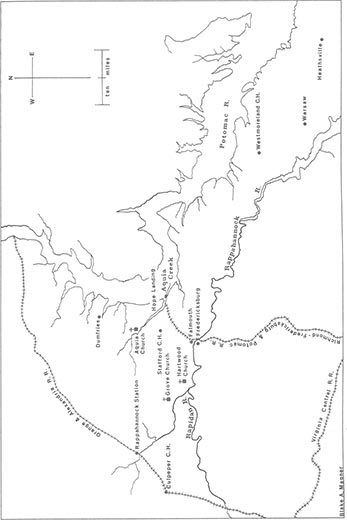

Brigadier General Fitzhugh Lee, General Robert E. Lee’s nephew, was Stuart’s favorite subordinate. Known as the “Laughing Cavalier,” Fitz Lee had a fun-loving nature but also engaged the Union cavalry numerous times during 1863. USAHEC.

The next day, General Averell learned that the enemy had fired on his pickets near Hartwood Church, and the uneasy division commander prepared to act. On the morning of February 24, word of an impending attack on his pickets reached the New Yorker. Averell’s vedettes spotted a squadron of Confederate cavalry lurking about Hartwood Church and reported their findings.37 Robert E. Lee wanted to know what Hooker’s intentions were, and the only way to find out was to penetrate the Army of the Potomac’s picket lines with a force of cavalry.38

On February 23, Stuart ordered Brigadier General Fitzhugh Lee, Averell’s old friend, to reconnoiter the Union picket lines at Hartwood Church.39 “We all loved Fitz Lee,” recalled a Southern officer. “His bright, sunny disposition made things happy and pleasant for all who were attached to his headquarters. Fond of fun, yet there was no one who commanded more respect when on duty or whose able services were more pronounced on the field.”40 Thomas L. Rosser sounded a similar note. He described Lee as “brave, buoyant and jolly.” His men happily followed Fitz Lee as he set off to make some mischief for his old chum. Fitz’s well-known sense of humor played a significant role in the foray he was assigned to lead.41

On the morning of the twenty-fourth, Lee led four hundred selected men of his brigade across the icy waters of the Rappahannock at Kelly’s Ford. His command included detachments of the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd Virginia Cavalry. Recent rains swelled the Rappahannock, and it had snowed heavily just two days earlier. The Confederate horse soldiers contended with mud, rain, and terrible roads in making the march, no small feat in the brutal Virginia winter. “On account of 18 inches of snow roads were miserable and almost impassable,” noted Lieutenant Colonel William R. Carter of the 3rd Virginia Cavalry in his diary.42 Carter’s adjutant described this journey as “one little expedition which I had like to have forgotten.”43 Lee’s little force spent the night of February 24 near Morrisville, a small settlement about five miles from the ford.44

The Federal right flank bent back from the Rappahannock, stretching to the north. The cavalry picket line ran about four miles to the west of an infantry picket line and passed through the intersection at Hartwood Church. The Telegraph Road and the Ridge Road extended to the east of the church, running parallel between one half and two miles apart, the Ridge Road running north of the Telegraph Road. The infantry picket line crossed these two roads about four miles east of Hartwood Church, in the direction of Falmouth. Since the formation of the Cavalry Corps in January, the Northern cavalry had done a good job of protecting the infantry picket lines and keeping Southern probes from finding that line. Because of his uncertainty about the precise whereabouts of the Army of the Potomac’s picket line, Robert E. Lee decided to send a mounted force to try to pierce the cavalry screen and see whether the Army of the Potomac’s infantry remained in force in the area around Falmouth.

On the morning of February 25, Fitz Lee moved out again and advanced on the Federal pickets near Hartwood Church, with the 1st and 3rd Virginia Cavalry leading the way. The Confederates stole up on a group of green pickets of the 16th Pennsylvania Cavalry. Wearing blue Union army overcoats, three Rebels approached a picket post manned by the inexperienced Pennsylvanians. A corporal halted them but allowed them to pass after only a moment’s delay. The three Southerners passed the picket post, abruptly wheeled, ordered the pickets to dismount, and took the unfortunate greenhorns prisoner.45 A number of Pennsylvanians retreated in the face of the Southern onslaught and were captured. James Roney, a trooper of the 16th Pennsylvania, was “retreating as fast as he could with the rebs close behind when his horse stumbled & threw James & he is a prisoner too.”46 The enemy soon appeared in force, and the situation appeared increasingly desperate.

Fitzhugh Lee’s Hartwood Church Raid, February 24, 1863.

At about two o’clock in the afternoon, the grayclad horsemen drove in the Federal pickets of the 3rd and 16th Pennsylvania near Hartwood Church. Lee split his column, sending it east on both the Telegraph and Ridge Roads. After piercing the main picket line, Lee attacked the picket reserve and main body, striking a sector manned by men of the 3rd Pennsylvania Cavalry. “Just as they started, a small squadron of cavalry passed out by us on a dead run,” recalled Charles H. Weygant of the 124th New York Infantry, whose regiment manned the infantry picket line several miles farther east. “Presently, they came dashing back, through a piece of woods just in front of us, in utter confusion. Several horses were riderless, and most of the riders hatless. The officers were waving their swords over their heads, vainly endeavoring to rally their men. Every few yards a horse would sink into the mud, and in plunging to extricate himself, would fall with his rider, and together they would wallow in the mire.”

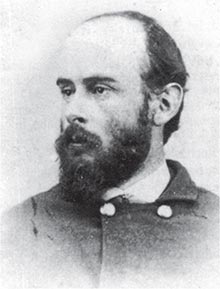

Captain Charles Francis Adams Jr. of the 1st Massachusetts Cavalry commanded part of the picket line that day. He and a small column of Federal troopers set out early that morning, riding west along the Ridge Road. “We looked on our business as a lark and rode leisurely along enjoying the fine day and taking our time.” Just as Lee’s troopers prepared to descend on the Federal pickets, Adams, Major Oliver O.G. Robinson of the 3rd Pennsylvania Cavalry, and Captain Benjamin B. Blood of Company G of the 4th Pennsylvania Cavalry (whom Adams described as “a curious nondescript…made up of dullness and whiskey”) entered the woods near the headquarters of the picket reserve. “Oh, there’s a carbine shot,” proclaimed one of the officers. A vedette challenged them, and Major Robinson rode forward to explain their business. More shots rang out, prompting Robinson to yell, “Hurry up, there’s a fight going on,” as he spurred off through the thick, knee-deep mud.

Captain Charles Francis Adams of the 1st Massachusetts Cavalry. The grandson of John Quincy Adams and great-grandson of John Adams, he possessed the family’s flair for words. His letters home are some of the best to be found. USAHEC.

“Well, I can’t hurry up in these roads, even if there is,” responded Adams. He found a good reason to hurry, though. The rookies of the 16th Pennsylvania and the veterans of the 4th New York came flying back from the direction of Hartwood Church, with Fitz Lee’s Confederates in hot pursuit. “Pell-mell, without order, without lead, a mass of panicstricken men, riderless horses and miserable cowards, our picket reserve came driving down the road upon us in hopeless flight. Along they came, carrying helpless officers with them, throwing away arms and blankets, and in the distance we heard a few carbine shots and the unmistakable savage yell of the rebels.” The officers drew their sabers and tried to block the flight of the fugitives—all from the green 16th Pennsylvania Cavalry. “Some only dashed past, but most obeyed us stupidly and I rode into the woods to try to form a line of skirmishers,” recalled Adams.

As he tried to cobble together a line, the high-pitched Rebel yell sounded nearby. His line vaporized, leaving the disgusted captain alone. “The panic seized my horse and he set his jaw like iron against the bit and dashed off after the rest.” The frantic animal dashed through the thick woods, knocking Adams’s feet from his stirrups, smashing him against a tree, and sending his hat flying. “I clung to the saddle like a monkey, expecting every instant to be knocked out of it and to begin my travels to Richmond.” A few hundred yards later, he got the frantic animal under control and found Robinson, who proclaimed, “My God, Adams! This is terrible! This is disgraceful!”

“Thank God,” replied the battered captain, “I am the only man of my regiment here today.”

“Well, you may,” responded Robinson.47

The Confederates also attacked the position held by Captain George N. Bliss’s pickets. Bliss commanded a section of the 1st Rhode Island’s picket line on the south side of the Telegraph Road. At about 1:00 p.m., Bliss heard the cheers of the advancing Rebels and knew that they had cut him off from the main picket line. He had orders to fight his picket posts and not to abandon them, so he made dispositions to do just that, even though his exposed position made him nervous and uncomfortable. He formed his little command of twelve men in a single rank across the road at the top of a hill facing toward the rear and the sounds of the enemy war cries.

As the enemy appeared, one called out to Bliss, “What regiment is that?”

“Advance one,” replied the captain.

“What regiment is that?” repeated the Rebel.

“What regiment is that?” countered Bliss.

“I ask you that question,” came the response.

“Advance one,” ordered Bliss.

“Are you rebels or Union?” inquired the confused Southerner.

“Union!” proclaimed Bliss with a shout. Stunned, the Confederates fell back, buying Bliss sufficient time to call in his pickets and order their withdrawal. The Confederates gobbled up some of the vedettes, but Bliss and most of the pickets escaped. He cobbled together a line of battle and repulsed two more Rebel forays before Lee broke off the engagement and withdrew. The next morning, Bliss learned that his little force of 12 men had stopped a Confederate column of 150 men and that the officer in command had reported the road ahead impassable, as an entire regiment of Yankee horsemen held it.48

“Those of my men that were taken were on their posts and I know that they fought like the devil before they were taken,” recounted Bliss. “I found two of my horses shot in the woods but so far as I know none of my men were killed, that is I could find no bodies so I consider them all prisoners.” He concluded, “If I had hesitated the other day I should now be on my way to Richmond. As it was I turned back several hundred men with 12 and escaped.”49

After pushing through Bliss’s pickets, Lee’s troopers encountered the Union picket reserve, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel John L. Thompson of the 1st Rhode Island Cavalry. Fortunately, the pickets had just been relieved, and the men had not made their way back to the reserve post, meaning that twice the normal number of Union horse soldiers held the picket line when Lee’s foray struck it. Thompson had six hundred troopers, consisting of two hundred men from the 16th Pennsylvania and one hundred men from each of the 3rd and 4th Pennsylvania, 4th New York, and 1st Rhode Island. These six hundred troopers had just relieved men under command of Lieutenant Colonel Edward S. Jones of the 3rd Pennsylvania Cavalry when the Confederates struck their position. Jones’s horsemen heard the infantry picket firing near Hartwood Church and moved out to the west along the Telegraph Road to try to check the Confederate advance.

Colonel Jones had ridden out to Hartwood Church to investigate the firing on the picket lines when an officer of the 16th Pennsylvania Cavalry hailed him. The frightened officer shouted that the Rebels were charging down the road. A bend in the road prevented Jones from seeing very far, “and in almost a moment a squad, filling the road and charging at full speed, commenced firing at me.” Jones, alone, turned his horse and rode through swampy ground to make his escape, the bog slowing the pursuing enemy horsemen.50

Jones ordered his small force of one hundred men to fall back slowly until he could find a better defensive position. These men fought hard, “with great gallantry and entirely checked the advance of the enemy, both flanks and threatened to their rear if they continued in that direction.” Jones rallied his men and instructed them to continue their fighting retreat. “As soon as our men turned the enemy charged and the retreat turned into a rout.”

Major Robinson of the 3rd Pennsylvania, the field officer of the day, arrived on the scene as Jones’s command broke and ran and, with assistance from Adams, “by almost superhuman efforts succeeded in halting and rallying some seventy-five men, whom he formed in line fronting the enemy, and delivered a terrible volley into them, checking their advance completely.” The Confederates returned fire, and Major Robinson instructed Adams to bring up his little line of thirty rallied men.

“I clearly can’t drive them,” thought Adams, “perhaps they’ll follow me.” Adams spurred his horse forward and called, “Come on, follow me, there they are!” and pointed his saber at the Confederates. His little column, instead of charging, melted away, to Adams’s fury. “Then wrath seized my soul and I uttered a yell and chased them. I caught a helpless cuss and cut him over the head with my sabre. It only lent a new horror and fresh speed to his flight. I whanged another over the face and he tarried a while,” recounted the furious captain. “Into a third I drove my horse and gave him pause, and then I swore and cursed them. I called them ‘curs,’ ‘dogs,’ and ‘cowards,’ a ‘disgrace to the 16th Pennsylvania, as the 16th was a disgrace to the service,’ and so I finally prevailed about half of my line to stop for this time.”51

After consulting with Adams, Robinson ordered and led a saber charge at the Wallace farm, known as Ellerslie, on the Ridge Road several miles to the east of Hartwood Church. Robinson had his horse shot out from under him, and his men retreated in confusion, trampling the major and bruising him badly. “He immediately got on his feet, and waving his saber rallied them, and mounting a riderless horse led them again in a charge on the enemy.” The charge killed two Confederates and wounded four others. They captured Captain John Alexander of the 2nd Virginia Cavalry and mortally wounded Lieutenant Edward W. Horner, capturing Horner and two privates.52 The Pennsylvanians briefly pursued the fleeing Confederates but soon called off the pursuit, content with their accomplishments.53

Adams found himself alone and isolated in the wake of the charge, his little command having retreated. He had dispatched Captain Blood and six of his men to the left, and the Pennsylvanians were captured.54 A Southern trooper raised his carbine, drew a bead on Adams, and squeezed off a shot. “I had never had a bead drawn on me before and the sensation was now not disagreeable.” As Adams rode off, he thought to himself, “You’re mounted, I’m in motion, and the more you aim the less you’ll hit.” The ball whizzed harmlessly by, and his antagonist spurred off. Adams soon saw troops moving and was greatly relieved to find the men of the 1st Rhode Island advancing in line of battle.55

Thompson’s Yankee horsemen formed line of battle in the following order: 1st Rhode Island on the right and 4th Pennsylvania, 4th New York, and 16th Pennsylvania on the left. As they finished aligning, Lee’s troopers fell on them with loud Rebel yells, charging on the Telegraph Road. In response, Thompson wheeled five squadrons to face the Confederates. Two of the squadrons—from the 16th Pennsylvania Cavalry—had never been under fire before, and they quickly broke and ran. The other remaining squadrons soon followed suit in spite of Colonel Thompson’s orders to draw sabers and charge.56

Captain Edward N. Chase, who commanded a squadron of the 1st Rhode Island Cavalry, had moved to protect Thompson’s rear with his own squadron and a squadron of the 16th Pennsylvania. He wheeled and led his little command over to the Ridge Road, not expecting to find a large force of Confederates charging toward him. To his surprise, Chase heard the clatter of cavalry horses to his rear, “and, to their great anger and mortification, in an instant almost, they were inextricably mixed up with the three retreating squadrons from Lieutenant-Colonel Thompson’s line.” Chase rallied the men and re-formed his line; Lieutenant Colonel Jones blunted Lee’s advance on the Ridge Road, and the Federals began planning a counterattack.57

Chase’s squadron, along with a squadron of the 4th New York, followed by the balance of the regiment, counterattacked, driving the grayclad horsemen back, exchanging fire the whole way. The Confederates made a stand at the slave cabins along Horsepen Creek on the William Irvine farm on the Telegraph Road about half a mile from Hartwood Church, and heavy skirmishing broke out again. Chase’s squadron, weary of the annoying skirmish fire, “gave a cheer for a charge, and away they went for the enemy, and, in less time that it takes to describe the stroke, had possession of the buildings.” A squadron of the enemy countercharged, putting Chase’s squadron to flight. A heavy volley by the dismounted Federal carbineers blunted the Southern countercharge, which ran out of steam. Chase had his horse shot out from under him, and he was briefly taken prisoner. However, he “was released by reason of the persuasive arguments of a few bullets from his men, who came to the rescue.”58

The Confederates fought as they retreated, leapfrogging regiments. One regiment made a stand while the others fell back and formed additional lines of battle behind it. The first regiment then pulled back and so forth. As a result, “the skirmish extended over a good deal of ground,” commented a Federal horseman.59 Lieutenant Colonel William R. Carter’s Confederate 3rd Virginia Cavalry made a stand and received orders to fall back and form behind the 1st Virginia’s line of battle. Carter learned that a Yankee regiment occupied the nearby woods and made his dispositions accordingly. He spotted an officer alongside the road, waving his handkerchief at the Virginian. “Learning from some stragglers that party probably belonged to the enemy & thinking it merely a ruse for the purpose of disentangling the men from the woods, I threw the Regiment ‘left into line’ to be ready to meet them in case they attempted to charge & advanced myself to meet the flag of truce,” noted Carter in his diary, “whereupon [an officer] of the 3d Penn. Cavalry surrendered himself & no men to me.” Another ten Federals also surrendered to the commander of the 1st Virginia. “This proved to be the party that was supposed to be a regiment of the enemy, & I immediately informed Gen. Lee to that effect.”60

As the Federals advanced, Lee ordered Carter to countercharge. The heavy, wet snow made charging difficult, but the Virginians valiantly rolled forward, charging east along the Telegraph Road.61 With the Rebel yell resonating, the 3rd Virginia crashed into the advancing column, disregarding flanking fire as the men bore down. “They continued to move on until we came in 30 yards of them, and then they broke & fled in perfect confusion,” proudly noted Carter. “Pursued them ¼ of a mile, killing & capturing several, when thinking we had pursued as far as prudence would permit or was in accordance with the designs of Gen. Lee, we halted the column, formed it ‘front into line’ & immediately received orders to return to the edge of woods and form in line facing the enemy, which I did.” Lee rode up and complimented the Virginians for their ferocious charge, “which compliment the men received with loud cheers.”62 Captain Richard Watkins, who commanded Company K of the 3rd Virginia, lost his horse in the charge. Watkins fell with the animal, and then the horse rose and dashed off toward the Union lines, leaving the bruised captain dismounted and alone.63

Early that bright, sunny winter morning, the men of the 124th New York Infantry of the Army of the Potomac’s III Corps departed from their camps near Falmouth, headed for their familiar position on the picket lines four miles to the east of Hartwood Church. “It was quite muddy. The roads seemed to be breaking up, and occasionally as we marched along one of the men would step in a hole and sink down almost to his knees,” recalled an officer of the 124th New York. When they arrived at Berea Church, four companies of New Yorkers moved toward the front lines to relieve the pickets. A rude surprise awaited them.64

Four miles to the east of Hartwood Church, Lieutenant Colonel Francis M. Cummins of the 124th New York, who commanded the infantry picket line, rallied his men and ordered them to advance. They opened fire on a body of Southern cavalry in their front. “The rebels evidently did not expect to meet any considerable force of infantry, for the moment we appeared, they went fours about, and dashed off as wildly as our cavalry had come in.”65 Before long, an entire Union infantry brigade had reinforced the picket lines.66 “An order came for us to be ready to fall in line at a moment’s notice as Stuart’s cavalry made a raid into our picket lines and they had a very exciting time out there and were driven in,” recalled a member of the 118th Pennsylvania Infantry.67

“The enemy did not succeed in accomplishing their designs, which were to capture our entire picket force around Hartwood,” observed Captain William Hyndman, commander of Company A of the 4th Pennsylvania. “The command deserved credit for their promptness in rallying for such a sudden emergency, and their conduct was favorably noticed in orders from Hooker.”68

Fitz Lee realized that while he had caught Averell’s men by surprise, his small force might be overwhelmed if the Yankees rallied and counterattacked. Further, the long-range rifles of the infantry gave the foot soldiers a decided advantage in range. Lee had accomplished his mission—he had found the Northern infantry and confirmed that it still occupied the area in force. Having accomplished his mission, Lee wisely withdrew and marched until late that night, finally encamping near Groveton on the old Second Bull Run battlefield.69

In the confused, whirling mêleé, Lee captured 150 prisoners, including 5 commissioned officers, as well as their horses and equipment. The prisoners included Lieutenant E. Willard Warren of the 3rd Pennsylvania Cavalry, who had just returned to his regiment after a stint in Richmond’s notorious Libby Prison. The Rebels captured the lieutenant when his horse fell and he could not get clear before the enemy pounced on him. Poor Warren started back to Libby the next day.70 Captain Isaac Ressler’s company of the 16th Pennsylvania Cavalry lost 4 men captured. That regiment lost a total of 30 prisoners.71 Most of Lee’s captives came from the cavalry and not from the infantry pickets in the vicinity of Hartwood Church.

Members of the 3rd Virginia Cavalry captured Lieutenant Francis D. Wetherill of Company K of the 3rd Pennsylvania Cavalry. Wetherill and a detail of twenty men had fought hard, escaping from one enemy trap. They marched along a narrow path through the mud and snow, surrounded by thick woods. Unexpectedly, a party of men in blue overcoats appeared in front of them. Believing them to be friendly, Wetherill did not act. Instead of friends, the men in blue turned out to be the 3rd Virginia Cavalry. Wetherill tried to order a charge, but the narrow road did not permit it. In a flash, the Pennsylvanians were surrounded and forced to surrender. They marched some distance to the rear, where they gave up their sabers and gave their names and units. An officer reviewing the list called out, “Who’s Wetherill?” The lieutenant presented himself, and the officer asked, “Are you the little Wetherill who used to go to Bolmar’s School?” When Wetherill affirmed his identity, the officer identified himself as Brigadier General William H.F. “Rooney” Lee, General Robert E. Lee’s second son, who had been Wetherill’s good chum at Bolmar’s School years earlier.72

Rooney Lee realized that his old friend was glum about his plight and tried to cheer him up. That night, Lee brought Wetherill a canteen of applejack whiskey and said, “Look here, Wetherill, don’t try to escape tonight and we’ll have a good time.” Without many options, Wetherill readily agreed, and the two spent the night sitting by the campfire, nipping from the canteen of applejack, reminiscing about happier days gone by. “At last, when sleepiness overcame us, we laid down together, in the snow, covered with the same horse blanket. When we awoke and got up the prints made by the bodies of the rebel and the Yankee were side by side in the snow.” That day, Wetherill began his long march to the hellish confines of Libby Prison.73

Fitzhugh Lee had light losses—four men killed, eight men wounded, and three men captured.74 The Virginian was pleased with his accomplishments in the terrible conditions. He left Dr. Charles R. Palmore, the regimental surgeon of the 3rd Virginia Cavalry, behind to care for his wounded. Lee, who “was the precise and punctilious soldier, with a great regard for all the etiquette of the profession,” could not resist tweaking Averell’s nose as he prepared to leave.75 As he departed, Lee left a taunting note and a bag of Virginia tobacco with Dr. Palmore for delivery to his old friend. “Dear Averell,” wrote Fitz Lee, “Please let this surgeon assist in taking care of my wounded. I ride a pretty fast horse, but I think yours can beat mine. I wish you’d quit your shooting and get out of my State and go home. If you won’t go home, why don’t you come pay me a visit. Send me over a bag of coffee. Good-bye, Fitz.”76 Not terribly amused, Averell grimly resolved to answer his old friend’s taunting invitation at the earliest possible opportunity.

Upon hearing the first shots, Colonel Jones sent a galloper to division headquarters to inform Averell that the enemy was attacking the picket lines near Hartwood Church. When Averell heard about the attack on the pickets, he scribbled a note back, instructing Jones, “If the enemy attack, whip them.”77 Averell quickly set his division in motion. “On receipt of the news at camp, we were ordered after the Rebels ‘double quick,’” reported Captain Walter Newhall of the 3rd Pennsylvania Cavalry.78

Word of the attack quickly reached Hooker. When they deftly evaded the infantrymen camped near Berea Church, Lee’s raiders passed within ten miles of Hooker’s headquarters east of Falmouth, engendering panic. Army headquarters instructed Averell to meet Fitz Lee’s raiders head on. As an incentive, Hooker’s chief of staff, Major General Daniel Butterfield, wrote, “General Hooker says that a major general’s commission is staring somebody in the face in this affair, and that the enemy should not be allowed to get away from us.”79 Averell had his men moving in a matter of a few minutes. “We were startled by the sounding of ‘Boots and Saddles,’” recalled a member of the 1st Rhode Island Cavalry, “and learned that the pickets had been driven in and threatened by Stuart’s cavalry. In line as quickly as possible, the brigade proceeded to Hartwood Church.”80

His advance hindered by the sloppy road conditions, Averell finally arrived at about 9:00 p.m. that night and found “disorder prevailing.” He jotted off a note to Butterfield, requesting that the Reserve Brigade be sent to reinforce him, and started looking for Fitz Lee. However, the Confederates had already withdrawn to Morrisville, twelve miles upstream from Hartwood Church and safely out of range.81 Not long after, a courier reined up, carrying further instructions from Butterfield. “The commanding general directs that you follow the enemy’s force; that you do not come in until the force which General Stoneman is directed to send out at 1:00 a.m. gets up with the enemy, and you have captured him or found it utterly impossible to do so,” wrote Butterfield. “Stoneman will endeavor to get between them and the river.”82 Averell’s men lit fires and stood to horse, waiting for further orders. They spent a long, cold night.83 “All the sleep I got last night I got lying on one rail,” complained a trooper of the 16th Pennsylvania Cavalry.84 Pleasonton, with the 1st Division, was on his way to reinforce Averell. Stoneman directed Pleasonton to march upstream with all possible speed, in the hope of cutting Lee off at the river fords.85

“About 2,000 of the enemy’s cavalry felt my pickets yesterday afternoon,” reported Hooker to Stanton. “Were repulsed, and Stoneman is now after them at full chase, with instructions to follow them to their camps, should it be necessary, to destroy them. These are on the south side of the Rappahannock, and near Culpeper.” Although the immediate danger had passed, Hooker grew angry that yet another Confederate foray had found his picket lines so porous.86

“That night, in the midst of a heavy rain storm ‘boots and saddles’ were sounded and the orders were to march,” recalled a member of the 8th Illinois Cavalry. “It was rumored that the rebel, General Stuart, was at his old tricks again. The men crawled from under their blankets, mounted their horses and started.” Retracing for nearly forty miles the route of Burnside’s Mud March, made just four weeks earlier, Pleasonton’s blueclad troopers never caught up to the Confederates, who had too much of a head start. “In addition to the severity of the weather, the location of the picket-line was an extremely dangerous one, as the country round was infested with bushwhackers,” noted a member of the 6th New York Cavalry.87

Pleasonton’s division arrived at Aquia Church early on the morning of the twenty-sixth after a long, miserable night in the saddle and halted. It did not push on, as Hooker had wanted.88 “Stood a few hours in the rain. Started together with three regiments on a wild goose chase after an imaginary Stuart,” groused an unhappy Hoosier. “Night found three brigades of us poor fellows shelterless, wet, cold, hungry, without rations or horse feed, shivering in the snow and water.”89

That morning, Pleasonton reported his whereabouts. “General Stoneman directed me to inform you when I should leave for Aquia Church,” he wrote at 3:00 a.m. “I have therefore the honor to report that the Second Brigade left its camp at 2:30 this morning and the First is about leaving. I shall move with the latter. One regiment is already at the Church, which is some 8 miles from here by the road which can now be traveled.…I shall not move beyond Aquia Church until I hear further concerning the rebel movements.”90 An unhappy Butterfield fired off a stinging note to Stoneman. After quoting Pleasonton’s report of his position, Butterfield noted, quite facetiously, “His brilliant dash and rapid movements will undoubtedly immortalize him!” He continued, “It is fair to presume that he failed to receive your orders to push on, otherwise I cannot account for his movements at all.” Butterfield then wrote to Pleasonton. “I don’t know what you are doing there,” he stated. “Orders were sent you at 11:00 p.m. last night, by telegraph and orderlies, to push for the enemy without delay, and to communicate with General Stoneman at Hartwood. The enemy have recrossed the river, at Kelly’s Ford, probably, and Averell is pursuing them.”91

Butterfield wanted to push out infantry forces to try to cut off the Southern horsemen from the Rappahannock fords. Coaxing, cajoling, and browbeating, Butterfield fired off telegram after telegram to the army’s infantry corps commanders trying to spur them to move. As an example, at 11:15 p.m. that evening, Butterfield wrote to Major General Samuel P. Heintzelman, commander of the forces assigned to the defenses of Washington, D.C., “The force is F. Lee’s and Hampton’s brigades.…Their horses are well tired. We are pushing all out tonight. Can you not push out tonight and push this side of the railroad at Rappahannock Station?” Try as he might, the chief of staff could not coax superhuman effort from the Army of the Potomac’s soldiers, and his frustration simmered into a boiling wrath.92

Averell’s men pursued as far as Morrisville before the general learned that Lee had crossed to safety on the other side of the Rappahannock. “We only seen one rebel & he had no arms, but we took him prisoner,” noted a Pennsylvanian in his diary.93 Lee blockaded the road with felled trees to slow the pursuit, and the tactic worked. The heavy overnight rains caused a “terrible flood,” as Averell described it.94 Pleasonton and his weary division arrived around 5:00 p.m. that afternoon, too late to be of any good. The Reserve Brigade, which had also made a forced march, accompanied by General Stoneman and his staff, arrived at nearly 4:30 a.m.

Stoneman roused the weary horse soldiers from their miserable bivouacs, and the entire column moved out, with Averell’s division in the lead. Stoneman remained at Hartwood Church, dispatching a few squadrons of Regulars to pursue the escaping Confederates. He soon learned that the Rappahannock was rising quickly and was impossible to cross. He had received orders from Hooker that “in the event of your inability to cut off the enemy’s cavalry, you will follow them to their camp and destroy them.” However, the river could not be forded. “After no little thought and some misgivings on the subject, I determined to move the whole of my available force down to the river that night, and at daylight the next morning push them at all hazards for the south bank of the Rappahannock, myself, of course, setting the example, a prospect anything but cheering,” reported Stoneman.95

Stoneman learned that Averell and Pleasonton had arrived at Morrisville. They found no signs of Lee or his brigade. At 4:45 a.m., Stoneman received an order directing him “that in case the enemy has re-crossed the Rappahannock and are on the other side, you will return with all your command to camp.” Stoneman communicated these orders to Averell and Pleasonton, and once they ascertained for certain that the enemy had, in fact, returned to the other side, Stoneman directed the entire force to head for its camps.96 By the time Pleasonton’s division made its way back to camp, it had traveled nearly eighty miles through horrible conditions, taking a severe toll on men and horses.97 “We had a hard trip—accomplished nothing!!” groused a Hoosier.98

Averell welcomed the orders to return to camp, which he gladly did, traversing terrible, muddy roads. “Settled down again into dreary camp life,” Averell noted in his diary.99 In fact, the return march was thoroughly unpleasant for all involved. “Arrived at camp after dark having been in our saddles all day except about 15 minutes at noon,” observed a member of the 16th Pennsylvania. “Horses no feed since last night & none since morning. Traveled about 40 miles today & nearly every step in the mud nearly to horses’ knees. Many horses gave out entirely & were left sticking in the mud. We are all horses and men completely plastered with Va. mud from head to foot and as tired as need be.”100 Sergeant Henry W. Owen, who also served in the 16th Pennsylvania, wrote to his sweetheart, “We have been out five days and nights chaseing the rebs and yet we are willing to soldier. We had a scirmish a short time a go killing several rebs driving them back a cross the Rappahanock River. We lost three killed forty seven taken. I expect we will soon have a nother brush. It may be before this reaches you.”101 Although Owen did not know it, his prediction was correct.

Northern newspapers quickly caught wind of Lee’s raid. “Another raid by Stuart’s horse thieves,” proclaimed a New York newspaper.102 “The rebels failed in accomplishing their object,” claimed a correspondent to the New York Herald, “and retreated in great haste across the Rappahannock, felling trees across the roads and placing other obstacles in the way of the pursuing force.”103

Jeb Stuart, however, saw it quite differently. Praising Lee’s command, the Confederate cavalry chieftain noted that Fitz Lee’s brief report of the action “shows how skillfully it was executed and how successfully it was terminated.” He continued, “Special attention is called to the commendations of the officers and men mentioned, to which I desire to add my high appreciation of the ability and gallantry displayed by Brigadier-General Lee in his prompt performance of the important duty assigned him.”104 Robert E. Lee also viewed the mission as a success. In a letter to President Davis, General Lee reported that his nephew Fitz “penetrated their lines five miles in rear of Falmouth, found the enemy in strong force, fell upon their camps, & brought off about 150 prisoners, killing thirty-six, & losing six of his own men.”105

“Everything here is perfectly quiet,” claimed Stuart in a letter to his brotherin-law. “Fitz Lee, whom I sent on a reconnaissance in rear of Falmouth was very successful indeed—bagging 150 and fighting heavy odds all the time. William H.F. Lee about the same time drove two gunboats out of the Rappahannock with two pieces of the Stuart Horse Artillery.” Indeed, it appeared that in spite of all of Hooker’s reforms, little had changed.106

Major General James Ewell Brown “Jeb” Stuart of Virginia commanded the Confederate cavalry forces assigned to the Army of Northern Virginia. Library of Congress.

Captain George N. Bliss, whose Rhode Islanders had fought hard after their initial surprise, gave an honest appraisal of the Union performance at Hartwood Church. Just a few days later, he wrote, “I am not surprised at the success of the rebels in this affair. Such an event has been predicted by many prophets among us, and unless our Genls. improve this lesson and make better arrangements on this flank of our army, the rebels will do the same thing again.”107 The performance of the Northern horse soldiers did not impress their counterparts in the infantry. “Our frightened cavalry, as an excuse for their disgraceful stampede, had reported a force of the enemy’s horse at least three thousand strong, in the act of swooping down on our picket line,” sneered an officer of the 124th New York Infantry. “The truth probably was that a strong reconnoitering party, having come across our small body of horse, made a dash at them and accidentally ran into our picket line.” Not surprisingly, the infantrymen claimed that they repulsed the Confederates, not the horse soldiers who carried the bulk of the day’s fighting.108

Neither Hooker nor Butterfield considered the expedition a Union success. Upon returning to camp, Stoneman received instructions “to have as soon as possible an exact report of the…movements in full of each portion of your command, and the delay of any portion to execute promptly and completely the part assigned it, together with the reasons therefor.”109 Hooker then summoned his cavalry chief to headquarters and exploded. “We ought to be invincible, and by God, sir, we shall be!” bellowed the army commander. “You have got to stop these disgraceful cavalry ‘surprises.’ I’ll have no more of them. I give you full power over your officers, to arrest, cashier, shoot—whatever you will—only you must stop these surprises. And by God, sir, if you don’t do it, I give you fair notice, I will relieve the whole of you and take command of the cavalry myself!”110 Clearly, no major general commissions could be expected any time soon.

Averell penned his report of the incident, now lost, on March 2 and apparently mentioned the note left by Lee in that missing report.111 When Hooker learned about Fitz Lee’s taunting note to Averell, he paid the division commander a visit. Averell, stung by his old friend’s needling, asked for permission to cross the river and settle his score with Lee. Hooker assured Averell that the division commander’s request would be granted soon. When Averell expressed confidence in his ability to even the score with Fitz Lee, Hooker said, “If you do there will likely be some dead cavalrymen lying about.” Some have misinterpreted this statement as suggesting, “Who ever saw a dead cavalryman?” as is often attributed to Hooker on this occasion. Averell’s response is not known, but the New Yorker was now determined to even the score with his old friend. He set about planning a mission to do just that.112

On February 28, Stoneman took stock of his command. In a letter to Hooker, he reported having 12,000 men and 13,000 horses fit for duty. His prior report showed 11,955 men and 13,875 horses, meaning that nearly 1,000 horses had been lost in a month.113 The harsh winter conditions had taken a terrible toll on the Cavalry Corps’s mounts, suffering in the cold climate of Virginia. “The cavalry horses look as if they came from Egypt during the seven years’ famine,” noted a foreign observer during the first week of March. “I inquired the reason from different soldiers and officers of various regiments. Nine-tenths of them agreed that the horses scarcely receive half the ration of oats and hay allotted to them by the government. Somebody steals the other half but every body is satisfied. All this could very easily be ferreted out, but it seems that no will exists anywhere to bring the thieves to punishment.”114 The willingness to turn a blind eye to such corruption would cost the Cavalry Corps dearly later that spring.

The men were also tired. “The line this force has to guard is but little less than 100 miles,” explained the Cavalry Corps commander. “Onethird on duty at one time gives 40 men to the mile on post at one time, and one-third of these gives 13 to the mile on post at one time. Considering the condition of the roads, it is a good day’s march to get out to the line and another to return, so that actually the horses are out one-half the time or more. Added to this the fact that frequently the whole cavalry force is in the saddle for several days together, and it will be perceived that but little more than one-third of the time is allowed the horses in which to recruit.” Stoneman apologized if it sounded like he was complaining and then concluded, “Should the general consider it expedient to diminish the amount of duty at present being performed by the cavalry, either by weakening or contracting the lines as now established, or by substituting a system of patrols for stationary vedettes, or in any other mode he may prescribe, I shall most gladly do so, and consider that the interests of the service have been benefited thereby.”115

Hooker approved the request. On March 2, Averell and Pleasonton received new instructions for picketing from Stoneman. Stoneman shortened the picket lines, and more frequent mounted patrols took the place of static vedette posts. “Patrols, mounted on the best horses, will be sent out on all the main approaches sufficiently often to keep you well informed of what is going on in your front. These patrols will not only watch all the main approaches, but will examine and thoroughly inspect the intervening country between these approaches.” Stoneman gave his division commanders discretion to set the size and strength of these patrols as they saw fit. These changes conserved horseflesh and marked another step in the long and painful process of educating the Army of the Potomac’s cavalry.116

Turmoil in the officer corps continued. Colonel Luigi Palma di Cesnola, the Italian count who commanded the 4th New York Cavalry of Averell’s division, was dismissed from the service in the second half of February for allegedly stealing government property. At the time, Di Cesnola commanded a brigade of cavalry as well as a detachment of infantry and a battery of artillery. The unhappy colonel protested, and the Judge Advocate General’s Office launched an investigation. It found that Di Cesnola “was most unjustly wronged,” and he was reinstated to his former rank and position. Di Cesnola wrote to Averell, asking, “In regard to my former position I heard that my brigade has been broken up & my Regt is under your command now; though I regret my command has gone yet it is gratifying to me to be under the command of a regular officer like you are.” Averell returned Di Cesnola to command of the 4th New York Cavalry, and the dashing Italian count proved himself a brave man in the coming months.

Although the injustice was corrected, this incident had cut Di Cesnola to the quick. “With what aching heart I return to my regiment few persons can appreciate it,” he wrote to his congressman a week later. “I tried ever to my utmost in well deserving from my adoptive country and the rewards I received from the Administration I may say were nothing but kicks.” He concluded, “I am…going to the Regiment with a broken heart to stay there some weeks and then I shall resign as it is incompatible with my character to continue.”117 The count did not resign and remained with his regiment, which had a troubled history for the duration of its service with the Army of the Potomac.118

The 8th New York drew ten days’ picket duty under unpleasant circumstances, standing four-hour shifts at a time. “Our duties are very arduous, men on duty 4 hours of 4,” observed a trooper on February 27.119 On the night of March 5, enemy cavalry broke through the picket line of Company K of the 8th New York located near Dumfries, well north of Falmouth, along the picket line in the rear of the army. They killed two men, wounded two, and captured seventeen more in another embarrassment for Stoneman.120 The next day, Grimes Davis, the brigade commander, directed that mounted patrols be beefed up. “These patrols are to be sent out often, especially at night, and on the best horses,” wrote Davis. “Orders from division headquarters require the line thoroughly observed and patrolled; and the colonel directs that if your present force is not sufficient, you make application for the number which you may consider necessary.” Davis concluded ominously. “The colonel commanding expects that your command will meet with no disgraceful surprise, such as occurred the other day in the Eighth New York.”121

Three days later, in a heavy rain, the men of the 6th New York Cavalry of Devin’s brigade drew up in line of battle, waiting for yet another enemy foray, picket firing having been heard. This time, though, the enemy was not Confederate cavalry. Instead, “it proved to be nothing more than the pickets firing at bushwhackers,” sneered a New Yorker, “a detestable set of cowardly sneaks who should have been shot at sight without challenge.” On the tenth, Pleasonton announced that the “noted Stuart” would pay the 1st Division a visit that night and “deliver a lecture at Ebenezer Church.” Eagerly anticipating the Bible lesson, and standing to horse on a stormy night, pelted by rain and snow, the 6th New York waited patiently, “with a full supply of tickets, but the lecturer failed to put in an appearance.”122

The 3rd Indiana Cavalry, of Pleasonton’s 1st Division, spent most of the winter picketing near Dumfries, “where the snow was deep and the heavy pine woods was thick with bushwhackers,” recalled saddler Augustus C. Weaver. “It was a nightly occurrence for some of our pickets to be fired on. We made good and killed several bushwhackers.” Being constantly on the alert and regularly under fire wore on the nerves of even these veteran horse soldiers, who eagerly awaited the coming of spring and the new campaigning season.123 On March 6, a nervous picket of the 3rd Indiana shot a lieutenant of the 8th New York who refused to dismount along the picket line.124

The Hoosiers of the 3rd Indiana itched for battle. “This command is now in good condition, notwithstanding the hard labor it has to perform and the winter’s exposure of the horses,” reported Colonel George H. Chapman, the regimental commander. “There are few, if any, regiments of cavalry in the service that have worn as well as this, but we are sadly in need of reinforcements to be put on a working par with the regiments with which we are associated.” The 3rd Indiana, which had elements serving in both the Army of the Potomac and the Army of the Cumberland, was smaller than the other regiments in its brigade. Chapman wanted two new companies raised in the fall of 1862 sent to him to increase the size of his command. “It is because of this disadvantage that I am so desirous the new companies should be sent as I trust I do not annoy you with my importunities and can assure you that my desire is to preserve the reputation of the 3d Inda Cavy and reflect honor upon the State we represent.” Chapman, a lawyer with a way with words, concluded, “We have to contend against more or less jealousy on the part of Eastern troops, but we have another western regiment in the Brigade (8th Illinois) and together we hold our own.”125 The Hoosiers had no reason to hang their heads. Although a smaller regiment than most, it fought hard and well and brought great honor on its state over the course of the war.

Things soon returned to the normal tedium of winter camp life. “There is no sign of the Army of the Potomac moving from its present encampment soon that I can see,” observed Lieutenant Lucas of the 1st Pennsylvania. “In fact, I don’t think it can for a month yet on account of the weather. The roads are very bad yet.”126 Two days later, he observed, “I shall look with interest to the time when the weather will permit a move of the Army of the Potomac, when I hope to hear of our army achieving a most glorious victory. If we don’t whip them this summer I shall give up all hopes of ever whipping them.”127 A member of the 6th Ohio Cavalry expressed a similar sentiment: “I expect this army will move ahead just as soon as the roads will admit, and I do hope that we will not meet with any more reverses, for the soldiers are now down hearted enough. We want to gain a great victory to give the men confidence once more, but we must await the result with all the patience we can.”128

While the Union mounted arm had made strides since the formation of the Cavalry Corps, it still had room for further improvement. The affair at Hartwood Church proved that beyond all doubt. “This dash of Confederate cavalry…and the manner in which it was met, are interesting evidence as to the relative efficiency of the two opposing cavalries,” observed a Northern historian. “They show that Hooker’s and Heintzelman’s horsemen, and their commanders, had something to learn before they would be up to the standard of Lee’s. It is plain that the country beyond the Federal outposts was not adequately patrolled and that the troops were not proficient in turning out suddenly and promptly and getting on the march.”129

The pieces of the puzzle were all in place. It remained to be seen whether the Northern horsemen would be up to the heavy task that lay ahead of them. The Army of the Potomac’s new Cavalry Corps would get its chance to prove its mettle just a few days later, and the blueclad horse soldiers proved that they were equal to the task.

NOTES

1. German, “Picketing along the Rappahannock,” 35.

2. Henry W. Owen to Dear Emma, March 15, 1863, Howard McManus Collection.

3. Where 300 Gather, 2. Hartwood Church remains an active, ongoing, vibrant congregation today, nearly two hundred years after its founding. The 1858 sanctuary building remains in use. There are no lingering scars or signs of the vandalism described by so many Union soldiers.

4. Hyndman, History of a Cavalry Company, 47.

5. Instructions for Officers and Non-Commissioned Officers, 56.

6. Webb diary, entry for January 23, 1863, Schoff Civil War Collection.

7. Gilpin diary, entry for February 4, 1863, Gilpin Papers.

8. Tobie, History of the First Maine Cavalry, 109–11.

9. Glazier, Three Years in the Federal Cavalry, 118.

10. Dennison, Sabres and Spurs, 199–200.

11. Henry T. Bartlett to his brother, February 9, 1863, Civil War Miscellaneous Collection, USAMHI.

12. Ibid.; James Burden Weston to his mother, February 9, 1863, in Frost and Frost, Picket Pins and Sabers, 37.

13. Bartlett to his brother, February 9, 1863, Civil War Miscellaneous Collection, USAMHI.

14. Ibid.

15. Walter S. Newhall to his mother, February 9, 1863, Newhall Family Papers.

16. Bliss to Dear Gerald, February 10, 1863, Bliss Letters.

17. Frost and Frost, Picket Pins and Sabers, 37.

18. Bliss to Dear Gerald, February 19, 1863, Bliss Letters.

19. Lucas to his wife, February 26, 1863, Lucas Letters.

20. Ford, Cycle of Adams Letters, 1:246–47. Glanders is an extremely contagious bacterial disease often fatal to horses. Symptoms include swollen lymph nodes, nasal discharge, and ulcers of the respiratory tract and skin. Glanders is communicable to other mammals, including humans.

21. Webb diary, entry for January 22, 1863, Schoff Civil War Collection.

22. Delos Northway to his wife, February 22, 1863, included in Souvenir, 108–10.

23. Redman to his sisters, February 8, 1863, Redman Correspondence.

24. New York Herald, February 18, 1863.

25. John Wilder Johnson to his wife, February 15, 1863, Olive Johnson Dunnett Collection.

26. Jasper Cheney diary, entry for February 20, 1863, Civil War Times Illustrated Collection, USAMHI.

27. Norton, Deeds of Daring, 56–58.

28. Samuel M. Potter to his wife, February 21, 1863, Potter Letters, Pennsylvania State Museum and Library.

29. Winder, Jacob Binder’s Book, 144.

30. Fell to Dear Lydia, February 22, 1863, Civil War Miscellaneous Collection, USAMHI.

31. Covert to his wife, February 22, 1863, Covert Letters.

32. Gilpin diary, entry for February 22, 1863, Gilpin Papers.

33. William Woods Averell diary, entries for February 22–23, 1863, Gilder-Lehrman Collection, J.P. Morgan Library.

34. Hall, Sixth New York, 93–4.

35. OR, vol. 25, part 2, 95–96.

36. Davis, Common Soldier, Uncommon War, 350–51.

37. Averell diary, entry for February 24, 1863, Gilder-Lehrman Collection.

38. Lee, Wartime Papers of R.E. Lee, 1:409. A few days earlier, elements of the 4th Virginia Cavalry had crossed the Rapidan at U.S. Ford. They crossed the flooded river and soon found a strong force of Union cavalry pickets, meaning that the Virginians could not proceed farther, so they withdrew without ascertaining the intentions of the Army of the Potomac.

39. Here is Averell’s description of his old friend Fitz Lee, as stated in his postwar memoirs: “Fitzhugh Lee was a sturdy, muscular, and lively little giant as a cadet. With a frank, affectionate disposition he had a prevailing habit of irrepressible good humor which made any occasions of seriousness in him when in ’61 he was compelled to choose between his state and the Nation and we came to the parting of the ways, the tears which suffered his eyes and the lamentations that escaped his lips betrayed a depth of feeling which revealed a sincere character beneath his habitual cheerfulness.” Eckert and Amato, Ten Years in the Saddle, 49.

40. Booth, Personal Reminiscences of a Maryland, 116.

41. Rosser, Addresses of Gen’l T.L. Rosser, 25.

42. Carter, Sabres, Saddles, and Spurs, 46.

43. Robert T. Hubard Memoir, Alderman Library, Special Collections.

44. OR, vol. 25, part 1, 25–26.

45. Brooke-Rawle, History of the Third Pennsylvania Cavalry, 190.

46. Potter to his sister, March 2, 1863, Potter Letters.

47. Ford, Cycle of Adams Letters, 1:255–57.

48. Dennison, Sabres and Spurs, 204–5.

49. Bliss to Dear Gerald, February 28, 1863, Bliss Letters.

50. Brooke-Rawle, History of the Third Pennsylvania Cavalry, 190.

51. Ford, Cycle of Adams Letters, 1:257–58.

52. New York Times, February 28, 1863.

53. Philadelphia Inquirer, February 28, 1863.

54. Not surprisingly, Captain Blood resigned his commission after his exchange at the end of May 1863. Bates, History of the Pennsylvania Volunteers, 2:550.

55. Ford, Cycle of Adams Letters, 1:260–63.

56. Dennison, Sabres and Spurs, 201–2.

57. Ibid., 202.

58. Ibid., 203.

59. Potter to his sister, March 2, 1863, Potter Letters.

60. Carter, Sabres, Saddles, and Spurs, 46–47.

61. Hubard Memoir.

62. Carter, Sabres, Saddles, and Spurs, 47.

63. Hubard Memoir.

64. Weygant, History of the One Hundred and Twenty-Fourth Regiment, 85.

65. Ibid.

66. OR, vol. 25, part 1, 21.

67. John L. Smith to his mother, March 3, 1863, FSNMP.

68. Hyndman, History of a Cavalry Company, 51.

69. Ibid.

70. Brooke-Rawle, History of the Third Pennsylvania Cavalry, 188, 194.

71. Ressler diary, entry for February 25, 1863, Civil War Times Illustrated Collection, USAMHI; Norman Ball diary, entry for February 25, 1863, Connecticut Historical Society.

72. Brooke-Rawle, History of the Third Pennsylvania Cavalry, 193.

73. Ibid., 193–94.

74. OR, vol. 25, part 1, 24–25.

75. Bond, “Fitz Lee in the Army of Northern Virginia,” 421.

76. Hess, “First Cavalry Battle at Kelly’s Ford, Va.,” part 1. Dr. Palmore spent three pleasant weeks at the headquarters of the 3rd Pennsylvania Cavalry before he returned to his regiment. In the meantime, he resumed an old friendship with a cook for the Pennsylvania saddle soldiers. Hubard Memoir.