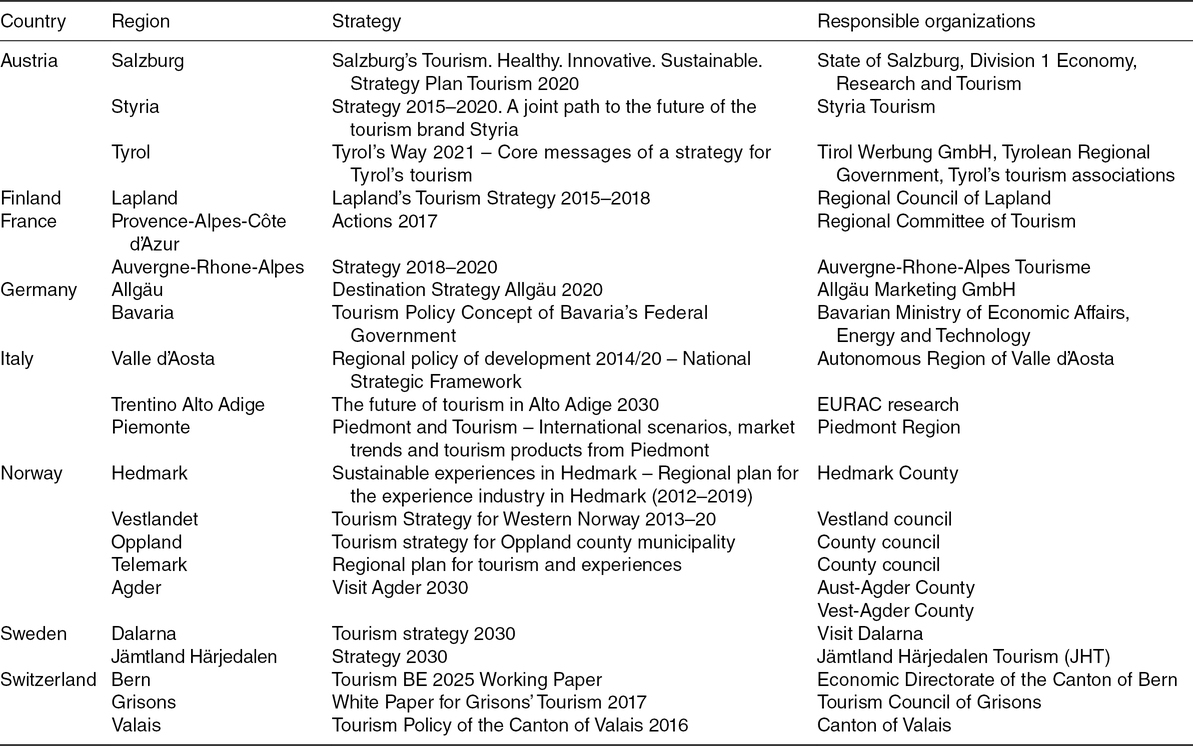

Table 5.1. Sample of examined regional tourism strategy and policy documents.

1Department of Geography, Umeå University, Umeå, Sweden; 2Centre for Tourism and Leisure Research (CeTLeR), School of Technology and Business Studies, Dalarna University, Falun, Sweden

* E-mail: dorothee.bohn@umu.se

Snow and ice are the defining elements of winter tourism (König and Abegg, 1997; Elsasser and Messerli, 2001; Franch et al., 2008; Rixen et al., 2011). Glaciers, snow-covered tundra, mountains or Scandinavian fells provide domestic and international tourists alike a wide range of winter holiday experiences. In some regions, winter tourism is centred in resorts that offer downhill skiing, snowboarding and après-ski partying, whereas in others, cross-country skiing and nature-based activities like snow hiking, snowmobiling, ice skating, husky tours and aurora borealis safaris are dominating the market (Tervo, 2008). The Christmas industry also attracts also plenty of travellers during the winter season and is of great significance in Northern and in Central European regions. Locally distinct hospitality cultures contribute to the heterogeneity of the winter travel product as well. Yet, winter tourism is in transformation. In addition to changing trends in consumer demand, global economic fluctuations and intensified competition among European destinations that provoke innovation in the travel sector generally, winter tourism is particularly vulnerable to the effects of climate change (Bank and Wiesner, 2011; Rixen et al., 2011; Landauer et al., 2012; Dawson and Scott, 2013; Bonzanigo, et al., 2016). Research has concentrated therefore much on strategies of how the tourism sector can adapt to global warming (Abegg et al., 2007) since the winter season is of great importance in providing employment and, thus, keeping many rural areas across Europe populated (Pechlaner and Tschurtschenthaler, 2003; Franch et al., 2008). Tranos and Davoudi (2014) observe that those adaptation initiatives in winter tourism destinations are usually initiated as autonomous actions of individual businesses but comprehensive public policy and planning advances are needed in order to foster a resilient tourism economy in European regions. Nonetheless, not many winter tourism studies have paid attention to actual public planning initiatives. This chapter addresses this gap and examines tourism policy and planning documents of alpine, Arctic and subarctic regions in terms of:

• the challenges and trends in European winter tourism;

• the planned regional responses to those challenges and trends; and

• the future of European winter tourism from a policy and planning perspective.

The regional level was chosen as the scale of analysis because winter tourism is highly localized. While national policy and planning address tourism development at a fairly general level, regional planning caters more to the place-specific actualities of the tourism sector.

The need for tourism policy and planning through public bodies is widely acknowledged in the relevant literature (Inskeep, 1994; Hall, 2008; Harilal et al., 2018). The economic potency of tourism with its multiplier effect is not only attractive for governments in low- and middle-income countries but also in rural areas, where tourism is often seen as a replacement for declining primary production and as a means for regional development (Saarinen, 2007; World Bank, 2017). However, the growing demand and unrestrained supply of tourism entails often grave ecological and socio-cultural consequences as tourism research has diligently pointed out (e.g. Mathieson and Wall, 1982). International, national, regional and local level public bodies are therefore drawn into tourism for steering the sector’s development into rendering favourable economic outcomes for local populations while minimizing environmental and social harms as much as possible. The influential position of triple bottom line sustainability in tourism scholarship materializes also in prevailing approaches to define planning. Although there is no universally accepted definition, King and Pearlman (2009, p. 2) state that tourism planning is commonly outlined as ‘a strategic decision-making process about the allocation of resources, which aims to derive optimum economic, environmental and socio–cultural outcomes for destinations and their stakeholders’. There is also no common agreement how public policy ought to be defined but Goeldner et al. (2000, pp. 514–515) maintain that policies provide the bigger picture of ‘what’ should be done in long-term tourism development and determine ‘the rules of the game’ for further planning initiatives. Yet, said rule setting and the concrete implementation of tourism policies evolve along the lines of dominating political, cultural, economic and environmental paradigms of a society (Dredge and Jamal, 2015).

State authorities in Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries are usually not planning tourism in an isolated, top-down manner but adopt instead a coordinating role inside a network comprising private sector bodies and community members (Laws et al., 2011). Planning rests therefore frequently upon public–private partnerships and is overall rooted in the concept of governance (Volgger and Pechlaner, 2014). Governments foster tourism commonly through infrastructural development, business subsidies, funding of marketing efforts and the provision of tourism education for a skilled workforce (Hall, 2008, p. 48). Legislation-based statutory policy and planning procedures for tourism relate to visa and entry regulations, labour law, the use of national parks, ownership structures and building regimentations (King and Pearlman, 2009, p. 8). In addition to statutory planning, many national, regional and local tourism authorities engage in indicative planning that provides a non-binding vision of how the travel and hospitality sector is desired to develop (King and Pearlman, 2009, p. 9). Especially strategic planning is employed nowadays as a dynamic approach to integrate planning and management into a single process rooted inside a governance network (Scott and Marzano, 2015). The goal of strategic planning is to match touristic demand and global trends with local supply while considering the interests of various destination stakeholders (Inskeep, 1994, p. 5). Destination management organizations (DMOs) across Europe, which are often semi-public structures and function traditionally as cooperative marketers and coordinators, engage in this respect increasingly also in strategic destination planning (Flagestad and Hope, 2001).

Winter tourism is an important economic pillar in many rural regions of the European Alps (Elsasser and Bürki, 2002; Soboll and Dingeldey, 2012; Tranos and Davoudi, 2014) as well in the Nordic countries (Tervo, 2008; Brouder and Lundmark, 2011; Tervo-Kankare, 2011). Besides changing trends in consumer demand, global economic fluctuations (Franch et al., 2008; Steiger and Mayer, 2008; Falk and Hagsten, 2016) and intensified competition among European destinations (Müller et al., 2010) that challenge the travel sector in general, demand and supply of winter tourism are especially susceptible to climate change (Bank and Wiesner, 2011; Rixen et al., 2011; Landauer et al., 2012; Dawson and Scott, 2013; Bonzanigo et al., 2016). The predominant body of winter tourism literature seeks therefore to establish an understanding of climate change impacts, mainly at regional and local levels, due to the spatial variability of climatic conditions (Tervo, 2008; Soboll and Dingeldey, 2012).

With respect to planning, tourism research points out possibilities of overcoming climate change vulnerability through adaptation strategies (Müller et al., 2010; Bank and Wiesner, 2011; Landauer et al. 2012; Dawson and Scott, 2013; Bonzanigo et al., 2016). Mitigation strategies, like the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions, are often highlighted as even more vital in terms of counteracting the very cause of global warming (Elsasser and Bürki, 2002), but have received overall less attention in the relevant winter tourism literature. Due to the global nature of climate change, mitigating actions necessitate collective transnational arrangements while adaptation to warmer temperatures and less natural snowfall in addition to changing touristic consumption patterns can be realized at a local level through:

• Technological advancements, like artificial snowmaking, extensions in, or expansion to, higher altitudes and glacier areas, landscaping and slope grooming (Abegg et al., 2007).

• Financial tools like snow insurances and weather derivatives that protect against monetary losses but maintain tour operators’ loyalty (Bank and Wieser, 2011).

• Cooperation and mergers between winter tourism operators and resorts (Abegg et al., 2007).

• The development of year-round tourism and a broad product portfolio that is not based on snow (Unbehaun et al., 2008).

However, Tranos and Davoudi (2014) remark that those adaptation initiatives are to date largely undertaken autonomously by individual ski operators and in response to market forces. This perspective reflects also in the predominant focus of winter tourism research on the corporate level with the justification being that knowledge about private sector adaptation determinants enables policy makers to choose appropriate planning instruments and strategies (Hoffmann et al., 2009). Research articles conclude therefore frequently with recommendations for public planning in the light of climate change and alterations in the tourism market place while a small number of papers discuss indicative planning and policy selection explicitly. Adopting a case study approach, Bonzanigo et al. (2016) explore the first steps to a collaborative community approach to sustainable winter tourism planning on a municipal level, and Pechlaner and Tschurtschenthaler (2003) outline the role of tourism organizations in providing a policy basis for corporate success and leadership in market adaptation. In this regard, strategic planning and management issues in winter tourism destinations have gained some momentum. Flagestad and Hope (2001) propose a model of a winter tourism destination for strategic management analysis and Müller et al. (2010) as well as Pechlaner et al. (2009) look at rejuvenating strategies of mature alpine winter tourism destinations. Nonetheless, a recurrent finding, which is also addressed by Pechlaner and Sauerwein (2002) in their case study on South Tyrol, is the difficulties of formulating and implementing strategic plans inside a dynamic multi-stakeholder and multi-interest destination environment.

A conclusion that can be drawn from existing papers is the sentiment that strategic planning and policy in winter tourism destinations should provide a locally specific and enabling business framework for enterprises that facilitates adaptation to economic, environmental and social developments of global scale. Pechlaner and Tschurtschenthaler (2003) stress the significant economic role that small business tourism has had in keeping rural alpine areas populated. In this vein, the purpose of tourism policy and planning is also to provide a sustainable future for local communities. In practice, however, planning implementation and the conduct of tourism enterprises do not easily go hand in hand due to diverging interests and perceptions (Tervo-Kankare, 2011). Amending the largely prescriptive approaches to winter tourism planning, this chapter offers a comparative analysis of strategic planning and policy documents of alpine, Arctic and subarctic regions across Europe.

The purpose of this study is to analyse and compare policy and strategic planning documents of regions relying heavily on winter tourism. The website www.skiresort.info, which is promoted as the largest platform for detailed information on ski resorts (Ski Resort Service International, n.d.), was consulted in order to identify winter tourism regions in Europe. The most common way to classify the size of resorts is based on the number of visitors (Vanat, 2019, pp. 13–14). However, this figure can vary, while a classification according to criteria such as length of slopes and elevation difference of the resorts such as the website employs is not that subject to fluctuations (Size Saalbach Hinterglemm Leogang Fieberbrunn, n.d.).

Data collection proceeded according to the following steps:

• The largest ski resorts in Europe were chosen.

• Results: Italy, Andorra, France, Switzerland, Germany and Austria (Europe: ski resort size, n.d.).

• Andorra was excluded from further investigation due to language constraints.

• The largest ski resorts in Sweden, Finland and Norway were included.

• The regional tourism planning documents where the resorts are located were retrieved in a Google search.

It is important to note that the term ‘region’ is not universally consistent. It might refer to a subnational spatial entity that possesses a certain degree of jurisdictional autonomy, a loosely defined area that holds some cultural or natural communalities and receives tourism-related funding from central governments or a supranational territory (Church, 2004, p. 555; King and Pearlman, 2009, p. 418). In this study, all three types of region are present. Some touristic regions correspond to federal states and cantons, while the Allgäu region in Germany is located inside two German federal states and in Austria. In the case of Italy, France, Norway and Sweden, all regions have some degree of jurisdictional power. One exception is the region called Vestlandet, which is geographical and encompasses four regional authorities (fylke).

The obtained documents, presented in Table 5.1, differ considerably from each other, both in form and function since different public and private organizations with different objectives are involved in tourism policy and planning. Semi-public DMOs focus usually on marketing, communication and generating a tourism development vision relevant for all stakeholders. Policy and planning strategies put forward by public organizations address also broader issues such as regional development and land use. Most regional tourism strategies are available as PDF files but some are only outlined on a website.

A qualitative analysis approach was selected due to the heterogeneity of the sample documents. Unlike a quantitative word count analysis, which would have remained rather superficial and ambiguous with respect to the different languages of the texts, a qualitative take on the data allows for interpreting the presence, absence or degree of attention given to certain topics. Thematic analysis was chosen because it is a flexible ‘method for systematically identifying, organising, and offering insight into patterns of meaning (themes) across a data set’ (Clarke and Braun, 2014, p. 57). The aim is to detect implicit and explicit themes that are relevant to the specific research questions of a study (Clarke and Braun, 2014). In this case, the main emphasis is on semantic meanings presented in the planning documents, but the authors paid also attention to latent and omitted issues. A prominent example relates to sustainability and climate change, which are frequently left out entirely or are only superficially addressed subjects in policy documents (Landauer et al., 2017), yet this neglect creates meaning.

The analysis followed a deductive–inductive procedure. Initial themes were formulated based on information from previous studies on winter tourism. While reading through the policy and planning documents, additional categories emerged and were coded respectively. A list of codes was created and relevant contents were classified and summarized several times until a final conceptual map (see Fig. 5.1) was generated.

This map visualizes the main thematic areas relating to the challenges for European winter tourism and the main areas of regional planning responses. Four particular pressure areas for European winter tourism regions, namely the global economy, regional economic dependency, shifting tourist demand and climate change are discernible. These macro issues force destinations to plan locally. The examined documents recognize economic issues and shifting tourist demand as immediate concerns that are tackled by planning initiatives related to developing infrastructure, marketing and the tourism product offering. Cooperation between a multitude of regional stakeholders is fundamental for implementing planning objectives associated with aforesaid response areas. The situation of the regional economy is a central concern for regional tourism planning and the links to the global economy and customer demand are well addressed. Climate change, however, is described as a major threat to winter tourism, but stands in all examined documents rather isolated with planning responses targeting adaptation and to a lesser degree mitigation.

This section presents the main challenges for winter tourism identified in the regional policy and planning documents. While national level tourism planning sets the broad framework for tourism development in a country, regional and local tourism planning seek to balance effects and benefits of tourism in a place-specific manner (Inskeep, 1994). In the analysed policy and planning documents, the main pressure on winter tourism stems from three areas, namely economic factors, touristic demand and climate change.

Winter tourism is a major source of income for many regions in the European Alps and in Northern Europe (Unbehaun et al., 2008). Especially in rural areas where economic alternatives to winter tourism are lacking, the sector is important in providing employment for the local population (Grisons, p. 83; Aosta Valley, p. 42). Alpine and Nordic winter tourism is characterized by small to medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and entrepreneurship is in this respect very important for many regions. Tourism started often as a sideline business for primary producers, but due to structural changes, the provision of hospitality and experience services became a professionalized main occupation. In many regions, family-owned businesses are vital for the attractiveness of the tourism product (Tyrol, p. 25). Coinciding with the main goal of all regional plans to ensure growth of the tourism sector, it is emphasized that tourism companies should be ‘economically viable and competitive’ (Hedmark, p. 19). Yet, winter tourism is stagnating in many places in the Alps (Müller et al., 2010) and this circumstance is also well recognized in the policy and planning documents. The dominant strategic reaction is to encourage development of the spring, summer and autumn offer with the goal to create year-round tourism and achieve higher capacity utilization, especially for cable cars. Also in Finnish Lapland, where winter tourism is constantly growing, the strategy targets the extension of the summer season in order to stabilize year-round tourism employment and ensure overall sustainable development (pp. 5–6).

Norway and Switzerland as non-members of the European Union (EU) and the Economic and Monetary Union (EMU), face economic difficulties with respect to price levels and unfavourable exchange rates. The respective regions describe themselves in the strategy and planning documents as being expensive. For the Swiss regions, competition with other European winter destinations is portrayed as particularly fierce. The strategy papers of the Norwegian regions also mention the well-paid workforce putting pressure on consumer prices. The UK exit from the EU is highlighted in the tourism strategies of the Provence-Alpes-Côte d’Azur (pp. 30–31) and the Canton of Grisons (p.36) as a question mark for the future in terms of incoming tourists.

Many rural European regions are highly dependent on (winter) tourism due to structural decline of primary production and the lack of economic alternatives. This puts pressure on the regions to maintain a profitable tourism sector. In addition, the situation of the global economy constitutes a strong influence on winter tourism. The predominant strategic planning response in adhering to economic growth is to develop year-round tourism.

Trends in demand and developments in existing and emerging geographical target markets are aspects that all of the documents pay much attention to. Health, longing for nature, interest in regional, authentic products, environmental consciousness and safety are identified as the leading consumer movements that ought to be incorporated into the tourism offering. The ageing traveller, however, receives in the majority of tourism plans particular consideration as a wealthy and quality-conscious customer who is willing to spend more for superior services and facilities (Salzburg, p. 13). This issue relates to the emerging discussion on accessibility for the elderly and people with disabilities in tourism literature. Ambrose (2012) argues that improved accessibility can facilitate more customer-centric products plus a competitive edge in the international market. Nonetheless, only the Italian documents address accessibility for disabled people explicitly (Piedmont, pp. 49, 117–118; Trentino Alto Adige, p. 11). Vestlandet (pp. 8–9), Hedmark (pp. 16–19) and Piedmont (pp. 117–118) write that impairment should not exclude anyone from having safe and memorable holiday experiences. Finnish Lapland adopts an ‘accessible hospitality’ approach, which emphasizes an accessible destination for everyone (p. 43). Similar advances are undertaken by the Italian, Norwegian and Swedish strategies.

Many policy and planning documents indicate that the European markets are stagnating and the Styrian tourism strategy adds that domestic and German markets are extremely weather- and public holiday-dependent (p. 8). Therefore, further internationalization of target markets is suggested. Grisons prioritizes also geographical segments outside of Europe and hopes to attract customers who are willing to pay more for quality experiences in Switzerland since the amount of guests from neighbouring countries has strongly declined (p. 36). Like in all the other regional policy and planning documents, the Middle East, Brazil, India, China and other Asian countries are pointed out as new promising generating areas.

The internet has become a leading platform for marketing communication and booking. All regions stress the need for approaching the customer online and providing convenient ways to find information about the destination and to make reservations. Social media as well as tourism 4.0, which embraces big data collection in order to create personalized travel experiences (Arctur, 2018), are seen as vital ways for offering products and engaging the consumer emotionally. Packaging and touring products are ways to enhance the value for the traveller while increasing the revenue of the tourist for the region based on digital optimization and are particularly advocated by Grisons (p. 55), Bern (pp. 10–11), the Aosta Valley (p. 42) and Dalarna (p. 14).

Almost all examined plans underline the need for customer research to ensure demand matches regional supply. In order to respond to consumer trends, diversification of the destinations’ product portfolio is promoted. The projected implication on winter tourism is that traditional downhill skiing will be of less importance in the future. The ageing tourist and people from non-European countries, who are pointed out as a very important segments, are not seen as downhill skiing enthusiasts in the examined documents. Moreover, a decline in domestic demand is feared if the young people are not actively introduced to skiing as a hobby.

Unique scenery and natural landscapes are the leading marketing images of alpine and Northern European regions. Beside picturesque natural environments, winter tourism is heavily dependent on snow (Elsasser and Messerli, 2001; Franch et al., 2008). Yet, climate change is the major threat to winter tourism in terms of snow insecurity as tourism research has diligently pointed out (Bank and Wiesner, 2011; Falk, 2013). The effects of a warming climate and diminishing snow reliability are well acknowledged for winter tourism in the majority of the documents. The responses to climate change on a regional level vary in the plans. Tyrol aspires to develop a research-based tourism climate strategy in addition to ecological traffic, mobility and spatial planning initiatives (p. 34). Salzburg wants to become a destination with a ‘green image’ and builds its tourism strategy on sustainable actions such as fostering public transport, education and energy efficiency (p. 39). Similar plans are adopted by the Aosta Valley (pp. 38; 62–68). Nevertheless, the dominant approach to climate change is diversifying the tourism product range. Rising temperatures are frequently perceived as a threat to winter but a benefit for summer and autumn tourism and new products like ‘summer mountain retreat’ and ‘Indian summer’ are brought up in the strategy document of Grisons (p. 44). Salzburg plans to develop its winter tourism product portfolio towards non-snow-dependent winter and Christmas experiences (p. 29). The regional strategies of Norway do not even address climate change at all. Styria seeks to achieve a green brand image and declares nature as a core tourism resource but no climate or sustainability policies are presented (p. 18).

Nonetheless, the lack of substance and concrete guidance in policy and planning documents for tourism stakeholders addressing climate change is quite notable and reinforces the findings of Landauer et al. (2017). The lack of specificity and clear goals for policies that deal with sustainability is also criticized by Grant et al. (2018). An outstanding example of ‘greening’ mainstream tourism development is the plan for the region Jämtland Härjedalen in Sweden, in which the authors state: ‘More and sustainable direct flights need to be established to the region (…)’ (p. 7). This statement is an antithesis: the will is to provide ‘more sustainable flights’, but at the moment there is no alternative to fossil fuel and emissions contribute to global warming. It is also doubtful that direct flights would make any changes in terms of sustainability if the guests have short stays in the region.

Climate change is a force to be reckoned with for winter tourism planning. Yet, it seems difficult for tourism-dependent regions to address climate change in a holistic manner. The predominant adaptation strategy is to diversify the destinations’ product portfolio towards snow-independent activities and other seasons. Mitigation efforts in regional planning focus on the improvement of public transportation and energy efficiency. Nonetheless, the economic growth paradigm persists in all regions and attracting more long-haul international travellers leads to greater carbon emissions. Beside the necessity for economic growth, the global nature of climate change makes effective mitigation a challenging task and planning for adaptation on a regional level seems less challenging.

Many of the examined documents provide strategies for winter tourism development in the region in response to economic pressures, shifting customer demand and also to climate change. Actions focus concretely on developing infrastructure, marketing and product offerings in a collaborative manner. Indeed, cooperation between public and private bodies is highlighted in all planning papers as a vital precondition to achieve a future-oriented and competitive tourism sector.

Infrastructure includes all basic systems that are required by a country to be able to function properly (Infrastructure, n.d.) and is an essential constituent in every tourist destination and directly linked to its competitiveness (Akama, 2002, p. 2). Hence, all policy and planning documents single out infrastructure as an area that has to be adapted to shifting consumer demand and climate change so that tourism remains economically profitable. The strategic approaches are either to upgrade, to construct more or to rationalize existing infrastructure and public–private partnerships (Weiermair et al., 2008). For Valais, it is important to create infrastructure that can be cooperatively used by agriculture and tourism (p. 31). In Switzerland and Norway, second home owners are crucial tourism stakeholders for several reasons. Grisons’ strategy paper states that second home owners are often forgotten in tourism development, although they are valuable customers for hospitality and tourism services and might play vital roles as regional ambassadors, advisers and investors (p. 71). In the Canton of Valais, two-thirds of the touristic added value derives from second home owners and the strategy seeks to involve those actors much more in the future (p. 11). Regional planning strives on the one hand to adapt winter tourism facilities to the needs of second home owners (p. 28) while, on the other, a tax for second home owners for tourism development and maintenance is considered (p. 17). In the Norwegian region Agder, more than half the tourists stay at private houses (p. 10) and Telemark points out the key role of second home tourists in achieving year-round employment in tourism (Telemark, p. 9).

Convenient accessibility, by plane, train and car is a requirement in all of the examined papers and for Finnish Lapland, ease of access constitutes a section in its overall touristic vision for the year 2025 (p. 5). Travelling by air is rising in popularity and the regions adapt to this trend by encouraging good connectivity to the main airports, such as in Norway (Hedmark, p. 16) and in France (Provence-Alpes-Côte d’Azur, pp. 2–5). The strategy document of Valais aims at short-trip and charter tourists from Europe and targets therefore the extension of the airport in Sion (p. 16). An effective transportation network inside the destination is favoured in Dalarna’s strategy (p. 12).

With respect to winter tourism, cable cars, slopes and accommodation facilities are crucial. The production of artificial snow has been one of the most popular infrastructural adaptation strategies to encounter snow insecurity (Elsasser and Messerli, 2001; Unbehaun et al., 2008) although large investments are required and maintenance is costly (Soboll and Dingeldey, 2012). The production of artificial snow is not only very energy-intensive and expensive but also leads to very high water consumption (Rixen et al., 2011). The only region that mentions potential issues regarding water management is the Aosta Valley (p. 42). Slopes are usually privately owned and artificial snowmaking is primarily incumbent on the operating companies rather than being an issue for public tourism authorities. Nevertheless, strict environmental requirements might be imposed on the installation of new equipment as is the case in Bavaria (p. 46). Merging ski resorts to larger areas and enhancing the attractiveness through size for the customer is a viable option for Bavaria (p. 46) and the Canton of Valais (p. 15) if investments are seen as long-term favourable. For small resorts in lower altitudes, which can be strongly affected by climate change, both regions opt for dismantling those facilities (Bavaria, p.46; Canton of Valais, p. 15). The Aosta Valley regional development plan acknowledges the risks for winter tourism operations at lower altitudes as well but without specific recommendations (p. 44). The Bavarian tourism policy paper underlines that there are enough external investors who are willing to spur bigger tourism development projects but the local population opposes such programmes frequently and it is therefore necessary to undertake far-reaching image campaigning for tourism (p. 15). The documents pertaining to the Italian regions highlight EU funds as a viable source of tourism development. The regional development plan for the Aosta Valley is even built around all the EU projects and programmes that can be a benefit for tourism and the region as a whole (Regione autonoma della Valle d’Aosta, 2015).

Cooperative marketing and product development is highlighted in all strategies as an important means to match demand and supply. All regions aim at expanding tourism products relating to culture, wellness, food and drink, meetings, incentives, conferences, and exhibitions (MICE), in addition to sports, where the focus is on hiking, biking and mountaineering. The goal is to develop products that are not season-bound. The aspired direction for winter tourism is to diversify the range of activities so that also non-skiers will be attracted. Bavaria seeks to achieve this through a marketing campaign called ‘SchneeBayern’ (SnowBavaria, author’s translation) in order to denote the versatility of the tourism offering beyond downhill skiing (p. 46). While Tyrol is very proud of its leadership role in alpine winter tourism (p. 27), Bern’s planning paper states that the traditional winter tourism infrastructure caters more to the ‘conventional guest’ and the existing product portfolio should be amended by ‘superior’ experiences offerings, especially in the cultural sector (p. 11). The marketization of culture is also advanced in the Norwegian, French, Swedish and Italian strategies.

Cable cars, which are predominantly utilized during winter, are encouraged to be operated also during the summer months so that the mountains become accessible in Switzerland and the Trentino Alto Adige (p. 53). Through dynamic yield management for skiing slopes Grisons seeks to attract more day trippers (p. 109) and Bavaria supports the combination of slope and public transportation tickets (pp. 44, 46). Winter sports competitions of national and international character are emphasized in the Swiss and Austrian strategy documents as important tourism marketing tools for the region worthy of receiving financial support. In Piedmont, the 2006 Winter Olympics functioned not only as a catalyst in attracting a record number of visitors during the event, but the trend continued also during the following years (pp. 138–144).

Although all regions identify the same global tourism trends, identical target markets and seek to develop similar product offerings, there is a strong emphasis on the idea that that customer value stems from local distinctiveness. Authenticity is a contested concept in tourism scholarship (e.g. Brown, 2013), but the analysed documents strongly accentuate the uniqueness of the regions’ nature and culture. The documents of Aosta Valley (p. 43), Vestlandet (p. 8) and Tyrol (p. 25) highlight not only the world-class winter sports landscape, but also the region’s authentic and excellent hospitality culture. This kind of local positioning relates strongly to branding, which has become an important communication tool in many examined regions. However, the brands for Tyrol, Finnish Lapland, the Allgäu region, Bern or Styria embrace also other economic and socio-cultural sectors. The goal is to create a holistic regional brand that exerts two functions, namely identification and distinction (Qu et al., 2011). The regional brand identity is quite similar for all the analysed regions: a thriving sphere for locals and tourists alike where wellbeing, innovation and ecological mindfulness are cultivated. Specifically for tourism, an important image conveyed in the brand is year-round attractiveness. The tourism strategy for Lapland mentions in this regard that a too-strong winter image is hindering the development of economically viable summer tourism (p. 17).

Given the global nature of tourism, the economy, plus the effects of climate change, the identified challenges for winter tourism are similar across the studied regions. Due to economic structural changes, rural alpine and Northern European regions are heavily dependent on (winter) tourism and the primary duty of planning is to sustain a profitable and competitive tourism sector. Economic growth is the overall strategic objective. Yet, winter tourism is often framed as problematic in the examined policy and planning documents because of stagnating tourist numbers and the future detrimental effects of climate change on snow security. The predominant planning initiatives focus therefore on the development of year-round tourism and product diversification. All planning documents recognize health, longing for nature, demand for regional products, environmental consciousness and safety as leading tourist trends that should be incorporated into the winter tourism offering. Those new products are especially tailored to the older traveller and non-European markets. The diversification of winter tourism towards non-snow-dependent products supports not only shifting customer demand but also the adaptation to climate change. Indeed, diversifying the tourism product is the principal adaptation strategy because it entails economic growth potential and the possibility for many regional tourism stakeholders to participate in the production of tourism. Mitigation strategies for climate change are either half-heartedly addressed or not addressed at all. Those findings are congruent to the existing body of winter tourism research.

The broad conclusion of the examined documents is that regional policy and planning in winter tourism advances development strategies away from winter as a distinct tourism season where downhill skiing or other snow-related outdoor activities dominate. Instead, winter is incorporated into a diverse, year-round product range. This planning approach seeks to encourage economic viability of the tourism sector in the future for many regional actors and buffer the negative effects of climate change in alpine and Northern European areas. Many examined regions pursue also place branding with the goal to convey an image of a destination that is attractive year-round and not just in winter. Thus, from a policy and planning perspective, winter tourism is going to transform from a distinct season to a versatile umbrella product.

Abegg, B., Agrawala, S., Crick, F. and de Montfalcon, A. (2007) Climate change impacts and adaptation in winter tourism. In: OECD (ed.) Climate Change in the European Alps: Adapting Winter Tourism and Natural Hazards Management. OECD Publishing, Paris, pp. 25–58.

Akama, J.S. (2002) The role of government in the development of tourism in Kenya. International Journal of Tourism Research4(1), 1–14. DOI:10.1002/jtr.318

Allgäu GmbH (n.d.) Destinations strategie 2020 [Destination strategy 2018–2020]. Available at: https://extranet.allgaeu.de/destinationsstrategie (accessed 29 October 2018).

Ambrose, I. (2012) European policies for accessible tourism. In: Buhalis, D., Darcy, S. and Ambrose, I. (eds) Best Practice in Accessible Tourism: Inclusion, Disability, Ageing Population and Tourism. Channel View Publications, Bristol, UK, pp. 19–35.

Arctur (2018) What is tourism 4.0? Available at: https://www.tourism4-0.org/#1_eng (accessed 29 October 2018).

Aust-Agder Fylkeskommune and Vest-Agder Fylkeskommune [Aust-Agder County and Vest-Agder County] (2015) Besøk agder 2030 [Visit Agder 2030]. Available at: http://regionplanagder.no/media/5967743/Besoek-Agder-2030.pdf (accessed 29 October 2018).

Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes Tourisme (2018) Strategie 2018–2020 [Strategy 2018–2020]. Available at: http://pro.auvergnerhonealpes-tourisme.com/article/plan-d-actions-marketing-2018 (accessed 29 October 2018).

Bank, M. and Wiesner, R. (2011) Determinants of weather derivatives usage in the Austrian winter tourism industry. Tourism Management 32(1), 62–68. DOI:10.1016/j.tourman.2009.11.005

Bayerisches Staatsministerium für Wirtschaft, Infrastruktur, Verkehr und Technologie [Bavarian Ministry of Economic Affairs, Energy and Technology] (2010) Tourismuspolitisches Konzept der Bayerischen Staatsregierung [Tourism Policy Concept of Bavaria’s Federal Government]. Available at: https://www.stmwi.bayern.de/fileadmin/user_upload/stmwi/Publikationen/2012/Tourismuspolitisches_Konzept.pdf (accessed 26 June 2019).

Bonzanigo, L., Giupponi, C. and Balbi, S. (2016) Sustainable tourism planning and climate change adaptation in the Alps: a case study of winter tourism in mountain communities in the Dolomites. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 24(4), 637–652. DOI:10.1080/09669582.2015.1122013

Brouder, P. and Lundmark, L. (2011) Climate change in northern Sweden: intra-regional perceptions of vulnerability among winter-oriented tourism businesses. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 19(8), 919–933. DOI:10.1080/09669582.2011.573073

Brown, L. (2013) Tourism: a catalyst for existential authenticity. Annals of Tourism Research 40(1), 176–190. DOI:10.1016/j.annals.2012.08.004

Church, A. (2004) Local and regional tourism policy and power. In: Lew, A., Hall, M.C. and Williams, A.M. (eds.) A Companion to Tourism. Blackwell Publishing Ltd, Oxford, UK, pp. 555–568.

Clarke, V. and Braun, V. (2014) Thematic analysis. In: Teo, T. (ed.) Encyclopedia of Critical Psychology. Springer, New York, pp. 1947–1952.

Comité Régional de Tourisme – Provence-Alpes-Cote d’Azur Tourisme [Regional Committee of Tourism – Provence-Alpes-Cote d’Azur Tourism] (n.d.) Actions 2017. Available at: https://web.archive.org/web/20170421062251/tourismepaca.fr/portfolio/strategie-et-actions-2017 (accessed 26 June 2019).

Dawson, J. and Scott, D. (2013) Managing for climate change in the alpine ski sector. Tourism Management 35, 244–254. DOI:10.1016/j.tourman.2012.07.009

Dredge, D. and Jamal, T. (2015) Progress in tourism planning and policy: a post-structural perspective on knowledge production. Tourism Management 51, 285–297. DOI:10.1016/j.tourman.2015.06.002

Elsasser, H. and Bürki, R. (2002) Climate change as a threat to tourism in the Alps. Climate Research 20(3), 253–257. DOI:10.3354/cr020253.

Elsasser, H. and Messerli, P. (2001) The vulnerability of the snow industry in the Swiss Alps. Mountain Research and Development 21(4), 335–339. DOI:10.1659/0276-4741(2001)021[0335:TVOTSI]2.0.CO;2

EURAC Research (2017) Il futuro del turismo in Alto Adige 2030 [The future of tourism in Alto Adige 2030]. Available at: http://webfolder.eurac.edu/EURAC/Publications/Institutes/mount/regdev/170526_Report_IT.pdf (accessed 29 October 2018).

Europe: ski resort size – best ski resort size in Europe (n.d.) Available at: www.skiresort.info/best-ski-resorts/europe/sorted/ski-resort-size (accessed 29 October 2018).

Falk, M. and Hagsten, E. (2016) Importance of early snowfall for Swedish ski resorts: evidence based on monthly data. Tourism Management 53, 61–73. DOI:10.1016/j.tourman.2015.09.002

Flagestad, A. and Hope, C.A. (2001) Strategic success in winter sports destinations – a sustainable value creation perspective. Tourism Management 22, 445–461. DOI:10.1016/S0261-5177(01)00010-3

Franch, M., Martini, U., Buffa, F. and Parisi, G. (2008) 4L tourism (landscape, leisure, learning and limit): responding to new motivations and expectations of tourists to improve the competitiveness of alpine destinations in a sustainable way. Tourism Review 63(1), 4–14. DOI:10.1108/16605370810861008

Fylkestinget [County council] (2011) Regional plan for reiseliv og opplevelser [Regional plan for tourism and experiences]. Available at: https://www.telemark.no/Vaare-tjenester/Naeringsutvikling/Reiseliv/Regional-plan-for-reiseliv-og-opplevelser (accessed 29 October 2018).

Goeldner, C.R., Ritchie, J.R.B. and MacIntosh, R.W. (2000) Tourism. Principles, Practices, Philosophies, 8th edn. John Wiley and Sons, New York.

Grant, J.L., Beed, T. and Manuel, P.M. (2018) Integrated community sustainability planning in Atlantic Canada: green-washing an infrastructure agenda. Journal of Planning Education and Research 38(1), 54–66. DOI:10.1177/0739456X16664788

Hall, C.M. (2008) Tourism Planning. Policies, Processes and Relationships, 2nd edn. Pearson Education Ltd, Harlow, UK.

Harilal, V., Tichaawa, T.M. and Saarinen, J. (2018) ‘Development Without Policy’: Tourism planning and research needs in Cameroon, Central Africa. Tourism Planning and Development, 1–10. DOI:10.1080/21568316.2018.1501732

Hedmark Fylkeskommune [Hedmark County] (2011) Bærekraftige opplevelsesnæringer i Hedmark (2012–2019) [Sustainable experiences in Hedmark – regional plan for the experience industry in Hedmark (2012–2019)]. Available at: https://www.hedmark.org/globalassets/hedmark/om-fylkeskommunen/planer/regional-plan-for-opplevelsesvaringer-2012-2017.pdf (accessed 29 October 2018).

Hoffmann, V.H., Sprengel, D.C., Ziegler, A., Kolb, M. and Abegg, B. (2009) Determinants of corporate adaptation to climate change in winter tourism: an econometric analysis. Global Environmental Change19(2), 256–264. DOI:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2008.12.002.

Infrastructure (n.d.) Meaning in the Cambridge English Dictionary. Available at https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/infrastructure (accessed 26 June 2018).

Inskeep, E. (1994) National and Regional Tourism Planning. Methodologies and Case Studies. Routledge, London.

Jämtland Härjedalen Tourism (JHT) (2016) Jämtland Härjedalen – Strategy 2030: for the tourism industry – ‘Jämtland Härjedalen – leaders in nature based experiences’. Available at: www.mynewsdesk.com/material/document/63068/download?resource_type=resource_document (accessed 29 October 2018).

Kanton Wallis (2016) [Canton of Vallais] Tourismuspolitik des Kantons Wallis [Tourism Policy of the Canton of Valais 2016]. Available at: https://www.vs.ch/documents/303730/740705/Walliser+Tourismuspolitik+2016/6d5a0fbf-671f-48b7-9c01-61a2bb5746f7 (accessed 29 October 2018).

King, B. and Pearlman, M. (2009) Planning for tourism at local and regional levels: principles, practices and possibilities. In: Jamal, T. and Robinson, M. (eds) The SAGE Handbook of Tourism Studies. Sage, Los Angeles, California.

König, U. and Abegg, B. (1997) Impacts of climate change on winter tourism in the Swiss Alps. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 5(1), 46–58.

Land Salzburg (2013) [State of Salzburg, Division 1 Economy, Research and Tourism] Salzburger Tourismus. Gesund. Innovativ. Nachhaltig. Strategieplan Tourismus 2020. [Salzburg’s Tourism. Healthy. Innovative. Sustainable. Strategy Plan Tourism 2020]. Available at: https://www.salzburg.gv.at/tourismus_/Documents/strategieplan_2020_-_internetversion.pdf (accessed 29 October 2018).

Land Tirol et al. (2015) [Federal State of Tyrol] Der Tiroler Weg 2021. Kernbotschaft einer Strategie für den Tiroler Tourismus [Tyrol’s Way 2021 – core messages of a strategy for Tyrol’s tourism]. Available at: https://www.tirolwerbung.at/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/strategie-tiroler-weg-2021.pdf (accessed 29 October 2018).

Landauer, M., Pröbstl, U. and Haider, W. (2012) Managing cross-country skiing destinations under the conditions of climate change – scenarios for destinations in Austria and Finland. Tourism Management 33(4), 741–751. DOI:10.1016/j.tourman.2011.08.007

Landauer, M., Goodsite, M.E. and Juhola, S. (2017) Nordic national climate adaptation and tourism strategies – (how) are they interlinked? Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism 2250, 1–12. DOI:10.1080/15022250.2017.1340540.

Lapin liitto (2015) Lapin matkailustrategia 2015–2018 [Lapland’s tourism strategy 2015–2018]. Available at: www.lappi.fi/lapinliitto/fi/lapin_kehittaminen/strategiat/lapin_matkailustrategia (accessed 29 October 2018).

Laws, E., Richins, H., Agrusa, J. and Scott, N. (2011) Tourist Destination Governance: Practice. Theory and Issues. CAB International, Wallingford, UK.

Mathieson, A. and Wall, G. (1982) Tourism, Economic, Physical and Social Impacts. Longman, London.

Müller, S., Peters, M. and Blanco, E. (2010) Rejuvenation strategies: a comparison of winter sport destinations in Alpine regions. Turizam: međunarodni znanstveno-stručni časopis58(1), 19–36.

Oppland Fylkeskommune [Oppland county] (2012) Reiselivsstrategi for Oppland fylkeskommun [Tourism strategy for Oppland county municipality]. Available at: https://www.oppland.no/Handlers/fh.ashx?MId1=1818&FilId=598 (accessed 26 July 2019).

Pechlaner, H. and Sauerwein, E. (2002) Strategy implementation in the alpine tourism industry. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management 14(4), 157–168. DOI:10.1108/09596110210427003

Pechlaner, H. and Tschurtschenthaler, P. (2003) Tourism policy, tourism organisations and change management in alpine regions and destinations: a European perspective. Current Issues in Tourism 6(6), 508–539. DOI:10.1080/13683500308667967

Pechlaner, H., Herntrei, M. and Kofink, L. (2009) Growth strategies in mature destinations: linking spatial planning with product development. Turizam: međunarodni znanstveno-stručni časopis 57(3), 285–307.

Qu, H., Kim, L.H. and Im, H.H. (2011) A model of destination branding: integrating the concepts of the branding and destination image. Tourism Management 32(3), 465–476. DOI:10.1016/j.tourman.2010.03.014

Regione autonoma della Valle d’Aosta [Autonomous Region of Valle d’Aosta] (2015) Politica regionale di sviluppo 2014/20 – Quadro strategico nazionale [Regional policy of development 2014/20 – National Strategic Summary]. Available at: www.regione.vda.it/europa/Politica_regionale_di_sviluppo_2014-20 (accessed 29 October 2018).

Regione Piemonte [Piedmont region] (2009) Piemonte e Turismo – Scenari internazionali, trend dei mercati e prodotti turistici piemontesi [Piedmont and Tourism – International scenarios, market trends and tourism products from Piedmont]. Available at: https://www.visitpiemonte-dmo.org/wp-content/files/Piemonte_e_Turismo.pdf (accessed 17 July 2019).

Rixen, C., Teich, M., Lardelli, C., Gallati, D., Pohl, M. et al. (2011) Winter tourism and climate change in the Alps: an assessment of resource consumption, snow reliability, and future snowmaking potential. Mountain Research and Development 31(3), 229–236. DOI:10.1659/MRD-JOURNAL-D-10-00112.1

Saarinen, J. (2007) Contradictions of rural tourism initiatives in rural development contexts: Finnish rural tourism strategy case study. Current Issues in Tourism 10(1), 96–105. DOI:10.2167/cit287.0

Scott, N. and Marzano, G. (2015) Governance of tourism in OECD countries. Tourism Recreation Research40(2), 181–193. DOI:10.1080/02508281.2015.1041746

Size Saalbach Hinterglemm Leogang Fieberbrunn (Skicircus) (n.d.) Available at: https://www.skiresort.info/ski-resort/saalbach-hinterglemm-leogang-fieberbrunn-skicircus/test-result/size (accessed 29 October 2018).

Ski Resort Service International (n.d.) Background information regarding the Skiresort online portal. Available at: www.skiresort-service.com/en/portal (accessed 29 October 2018).

Soboll, A. and Dingeldey, A. (2012) The future impact of climate change on Alpine winter tourism: a high-resolution simulation system in the German and Austrian Alps. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 20(1), 101–120. DOI:10.1080/09669582.2011.610895

Steiermark Tourismus (2014) [Styria Tourism] Strategie 2015–2020. Ein gemeinsamer Weg in die Zukunft der Tourismusmarke Steiermark [Strategy 2015–2020. A joint path to the future of the tourism brand Styria]. Available at: https://www.steiermark.com/de/b2b/unternehmen/strategie (accessed 29 October 2018).

Steiger, R. and Mayer, M. (2008) Snowmaking and climate change: future options for snow production in Tyrolean ski resorts. Mountain Research and Development 28(3), 292–298. DOI:10.1659/mrd.0978

Tervo, K. (2008) The operational and regional vulnerability of winter tourism to climate variability and change: the case of the Finnish nature-based tourism entrepreneurs. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism 8(4), 317–332. DOI:10.1080/15022250802553696

Tervo-Kankare, K. (2011) The consideration of climate change at the tourism destination level in Finland: coordinated collaboration or talk about weather? Tourism Planning and Development 8(4), 399–414. DOI:10.1080/21568316.2011.598180

Tourismusrat [Tourism Council of Grisons] Graubünden (2017) Weissbuch für den Bündner Tourismus [White Paper for Grisons’ Tourism 2017]. Available at: https://innovationgr.ch/news/6430/weissbuch-fuer-den-buendner-tourismus (accessed 26 June 2019).

Tranos, E. and Davoudi, S. (2014) The regional impact of climate change on winter tourism in Europe. Tourism Planning and Development11(2), 163–178. DOI:10.1080/21568316.2013.864992

Unbehaun, W., Pröbstl, U. and Haider, W. (2008) Trends in winter sport tourism: challenges for the future. Tourism Review 63(1), 36–47. DOI:10.1108/16605370810861035

Vanat, L. (2016) International report on snow and mountain tourism: overview of the key industry figures for ski resorts (Report No. 8). Available at: www.isiaski.org/download/20160408_RM_World_Report_2016.pdf (accessed 29 October 2018).

Vanat, L. (2019) 2019 International report on snow and mountain tourism: overview of the key industry figures for ski resorts (11th edition). Available at: https://www.vanat.ch/international-report-on-snow-mountain-tourism (accessed 26 June 2019).

Vestlandsrådet [Vestland council] (2012) Reiselivsstrategi for Vestlandet 2013–20 [Tourism strategy for western Norway 2013–20 opportunities]. Available at: https://www.hordaland.no/globalassets/for-hfk/naringsutvikling/filer/felles-reiselivsstrategi-for-vestlandet-med-innarbeidde-endringer-etter-behandling-i-vr-radet.pdf (accessed 29 October 2018).

Visit Dalarna (n.d.) Dalarnas Besöksnäringsstrategi 2030 [Dalarna’s tourism strategy 2030] – Visit Dalarna AB. Available at: https://www.visitdalarna.se/media/383 (accessed 8 February 2019).

Volgger, M. and Pechlaner, H. (2014) Requirements for destination management organizations in destination governance: understanding DMO success. Tourism Management 41, 64–75.DOI:10.1016/j.tourman.2013.09.001

Volkswirtschaftsdirektion des Kantons Bern (2018) Tourismus BE 2025. Arbeitspapier [Tourism BE 2025 Working Paper]. Available at: https://mmbe.ch/web/sites/default/files/2018-01-18-tourismus-2025-de.pdf (accessed 29 October 2018).

Weiermair, K., Peters, M. and Frehse, J. (2008) Success factors for public private partnership: cases in alpine tourism development. Journal of Services Research 7(February), 7–21.

World Bank Group (2017) Tourism for Development: 20 Reasons Sustainable Tourism Counts for Development. The World Bank, Washington, DC.