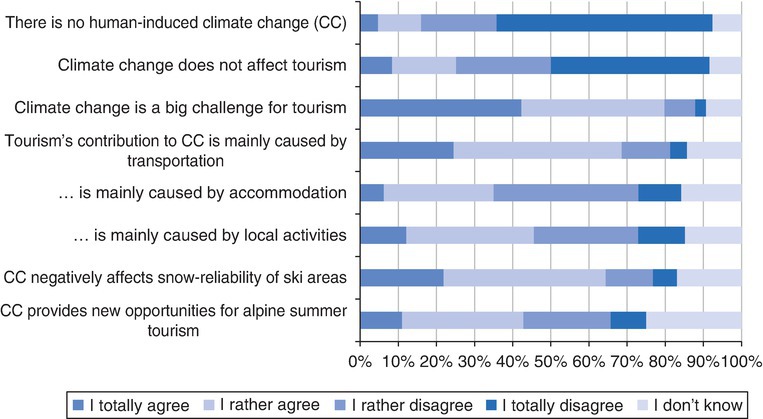

Fig. 8.1. Tourists’ consent to statements related to climate change and tourism (n = 482–514).

8 Alpine Winter Tourists’ View on Climate Change and Travel Mobility

1Institute of Geography, University of Innsbruck, Innsbruck, Austria; 2Institute for Systemic Management and Public Governance, University of St. Gallen, St. Gallen, Switzerland; 3alpS – Centre for Climate Change Adaptation, Innsbruck, Austria; 4Institute of Infrastructure Engineering, University of Innsbruck, Innsbruck, Austria

* E-mail: bruno.abegg@uibk.ac.at

Tourism is significantly contributing to climate change with transportation to/from the destination often being recognized as the primary contributor. In 2005, global tourism was responsible for 1.3 GtCO2 – this was approximately 5% of the world’s total CO2 emissions at that time, excluding other greenhouse gases (GHGs) and secondary impacts caused by aviation (UNWTO-UNEP-WMO, 2008). These emissions can be broken down into three categories: transport (75%), accommodation (21%) and activities (4%), with air travel alone being responsible for 40% (UNWTO-UNEP-WMO, 2008; Peeters and Dubois, 2010). A recent study, taking into account direct and indirect GHG emissions etc., found that global tourism is contributing much more to climate change: 4.5 GtCO2e or about 8% of the global GHG emissions in 2013 (Lenzen et al., 2018). Direct emissions from air transport (absolute numbers) are similar to previous research, however, the relative contribution of air transport to global tourism’s overall emissions is much smaller given that the approach is more comprehensive (see Lenzen et al., 2018 – supplementary information).

Different methods have been used to calculate tourism’s carbon footprint. Becken et al. (2003), for example, calculated the individual energy use (MJ) of domestic and international tourists in New Zealand. They found that transport is responsible for 73% of the domestic and 65% of the international tourist’s energy bill. The corresponding figures for the accommodation and attractions/activities sectors are 17%/22%, and 10%/13%, respectively. Notably, international tourists’ flights to/from New Zealand were not included in this analysis. Kelly and Williams (2007) calculated the energy consumption and GHG emissions (CO2e) for Whistler/Canada. Their results show that travel to/from Whistler is responsible for 80% of the total energy consumption and 86% of the total CO2e emissions in the municipality of Whistler. Air travel alone is responsible for 72% and 78%, respectively. Peeters and Schouten (2006) applied the ecological footprint concept to the city destination of Amsterdam. They found that 70% of tourism’s footprint is related to transport to/from Amsterdam, 21% to accommodation, 8% to local activities and 1% to local transport. Summarizing existing literature, most studies – independent of applied methodology – highlight the dominant role of transport, in particular of air travel, in contributing to tourism’s energy use and GHG emissions.

Energy and emission intensities in tourism, however, can vary significantly. This is due to the different markets (e.g. domestic, short-haul, long-haul), the different products (e.g. bicycle vs. cruise tourism), the distances travelled (which are usually related to a preferred mode of transport), and to the choice of accommodation and activities (e.g. Chenoweth, 2009; Gössling et al., 2015). Filimonau et al. (2014), for example, investigated short-haul tourism from the UK to France using life cycle analysis. They confirmed the general finding that travel to/from destination generates the largest carbon footprint, but for tourists arriving by coach and train, and staying longer, the destination-based elements of the vacation, in particular accommodation, can outweigh the transport elements.

Gössling (2010), named five measures to reduce tourism’s carbon footprint: (i) develop closer markets, (ii) encourage low-energy transport, (iii) reward visitors staying longer, (iv) encourage low-energy spending and (v) increase high-profit rather than high-turnover spending within the regional economy. Surprisingly little is known in terms of what tourists actually think about such measures. There is one exception: air travel (e.g. Becken, 2002; Cohen and Higham, 2011). Within air travel, it is (voluntary) carbon offsetting that gained particular attention (e.g. McKercher et al., 2010; Mair, 2011). This is related to another body of literature dealing with people’s unwillingness to change (air) travel patterns. Many tourists seem to know that their behaviour is harmful to the environment, they also might behave pro-environmentally at home but are reluctant to do so when it comes to travelling, displaying the often-cited awareness/attitude–behaviour gap (e.g. Barr et al., 2010; Hares et al., 2010; Lassen, 2010; Kroesen, 2013). The difference between ‘home and away’ (Barr et al., 2010) is further substantiated by a representative survey from Germany (Forschungsgemeinschaft Urlaub und Reisen e.V., 2007). The study shows that many people are willing to save energy at home (66% already do, 22% will do in future), to buy locally (and therefore to reduce distances) (37%/28%) and to drive less (31%/25%). The same people, however, are very reluctant when it comes to climate-friendly travel behaviour: the highest values got the option ‘one long trip instead of several short trips’ (25% already do, 15% will do in future), followed by ‘choosing a destination nearby’ (22%/16%), ‘less travelling in general’ (25%/12%), ‘less long-haul travel’ (26%/8%) and ‘train instead of plane/car’ (17%/15%). Options related to flying are least accepted: ‘voluntary carbon offsetting’ (5%/18%) and ‘avoid flying’ (15%/8%).

This is, briefly, the thematic background of a survey conducted in the alpine destination of Alpbach-Seenland (Province of Tyrol, Austria). Winter tourists (n = 518) were asked about the two-way relationship between climate change and tourism, measures to reduce tourism’s energy consumption and carbon footprint, and factors that might support more eco-/climate-friendly modes of transport for holiday travel in the future. The aim was to learn more about (i) the tourists’ level of knowledge, and (ii) their assessment of measures to reduce tourism’s carbon footprint. Results will be presented taking into account socio-demographic characteristics of the sample (age, gender, education, etc.), and implications will be discussed from the destination’s point of view.

The survey took place in Alpbachtal-Seenland (www.alpbachtal.at/en), a well-known destination in the province of Tyrol, Austria. The destination offers a wide range of winter sport activities in a mountain environment and accounted for 465,000 overnight stays in the winter season of 2016/17 (see www.tirol.gv.at for official tourism statistics). The survey was conducted in January and February of 2016. Tourists were randomly chosen at highly frequented places such as village centres, tourist offices and hotels; however, most tourists willing to fill in the questionnaire were found at the parking lot and in the restaurants and mountain huts of the ski area.

The questionnaire was available in German and English: German, because the majority of guests originate from German-speaking countries (Germany, Austria and Switzerland), and English, because – traditionally – the destination Alpbachtal-Seenland is very popular with tourists from the UK. A preliminary version of the questionnaire was pretested by a number of colleagues and regional tourism stakeholders resulting in minor changes with regard to structure and wording.

The questionnaire was organized in four sections: (i) general travel information (e.g. motives, accommodation, length of stay, etc.); (ii) travel mobility (e.g. transport to/from and within destination); (iii) tourists’ knowledge, measures to reduce carbon footprint and factors to facilitate more eco-/climate-friendly mobility in the future; and (iv) socio-demographics (age, gender, education, etc.). In this chapter we focus on section 3. In this section, tourists were asked to answer three questions:

• To judge several statements related to climate change and tourism (e.g. climate change negatively affects snow reliability of alpine ski areas). Answer options included: ‘totally agree’, ‘rather agree’, ‘rather disagree’, ‘totally disagree’ and ‘don’t know’. The aim of this question was to learn more about the tourists’ basic understanding of the relationship between climate change and tourism.

• To discuss several measures to reduce energy consumption while travelling (e.g. choosing a destination nearby). Answer options included: ‘already do’, ‘will do in the future’ (intention), ‘will not do in the future’ (refusal) and ‘don’t care’. The aim of this question was to learn more about the tourists’ attitudes towards some measures often cited in the literature.

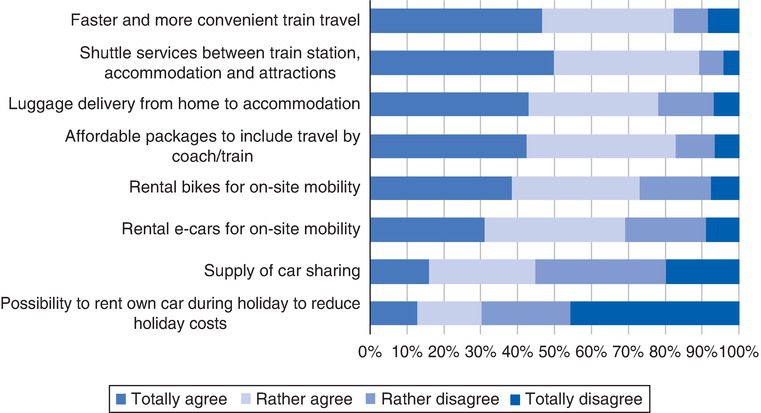

• To judge some prerequisites that must be given to potentially switch to a more eco-friendly mode of transport (e.g. shuttle service from train station to accommodation). Answer options included: ‘totally agree’, ‘rather agree’, ‘rather disagree’ and ‘totally disagree’. The aim of this question was to learn about the technical/organizational factors that might influence the willingness to change individual travel mobility behaviour.

Data were analysed using SPSS Statistics. To check whether there are statistically significant differences across socio-demographic groups (age, gender, education, etc.), appropriate tests (Kruskal–Wallis and Mann–Whitney U) were applied. The p values are given in the results section.

The survey sample (n = 518) is composed of slightly more males than females (51.0% and 49.0%, respectively). Average age is 42 years, with the largest share of respondents falling into the 31–50 age group (54.2%), followed by the respondents older than 50 years (25.3%). The largest number of respondents arrived from Germany (49.8%), followed by the UK (24.8%), Austria (9.9%), The Netherlands (3.7%) and other European countries (11.6%). Only 0.2% of the respondents were of non-European origin. A total of 69.3% of the respondents travelled by car (including rental cars and motor homes), 23.2% by plane, 6.0% by coach, 1.4% by train and the rest by other modes of transport. A total of 86.7% of the respondents spent at least 1 night at the destination, with the majority (71.2%) spending 3–7 nights, the remaining respondents were day visitors. Main reasons to visit the area were sport activities and relaxation, or a combination of both. A comparison with existing tourism data (Rauch et al., 2010; Manova, 2014) suggests that the sample is representative in terms of age structure and countries of origin. However, the day visitors are under-represented.

Figure 8.1 shows the surveyed tourists’ consent to several statements related to climate change and tourism. A clear majority of the respondents accepted anthropogenic climate change (76.4% rather or totally disagree with the statement that there is no human-induced climate change). Climate change not only has an impact on tourism; it is considered a big challenge for the tourism industry (42.3% of the respondents totally agree, 37.5% rather agree). Many respondents expect climate change to have negative impacts on winter tourism (= reduction in the number of snow-reliable ski areas) and positive impacts on summer tourism. Tourism also contributes to climate change, with transportation and local activities being regarded as the most important contributors (68.5% and 42.9% of respondents totally or rather agree). These results suggest that most respondents are familiar with some basic relationships between climate change and tourism. However, consent to specific statements varies among different types of respondents. Females (p = 0.003), younger persons (<30 years old; p = 0.007) and respondents with higher education (p = 0.018), for example, are more willing to accept human-induced climate change.

There are several ways to reduce energy consumption and related GHG emissions while travelling. A selection of measures was used in this survey, and the tourists were asked what they already do, what they might do in the future (intention), what they won’t do in the future (refusal) and what they don’t care about. Figure 8.2 shows that a majority of respondents already pays attention to reducing energy consumption by turning off lights, saving water etc. (72.1% of respondents) and by buying locally and organically produced goods (58.3%). A large share of respondents is willing to use eco-friendly modes of transport for local activities (34.1% already do, and 36.6% intend to do so in the future). In the future, 42.1% of the respondents might also choose an eco-friendly accommodation relying on renewable energies. When it comes to ‘real’ changes in travel behaviour (shorter distances, extended length of stay and less flying), respondents are much more reluctant, and many respondents strictly refuse to choose a destination nearby (34.1%), to do fewer but longer trips (instead of more, shorter trips; 36.9%), and to avoid flying (61.6%). Summarizing, many respondents are willing to pick the ‘low hanging fruits’ as long as it doesn’t interfere with the individual freedom to travel. Female respondents are generally more willing to reduce energy consumption and GHG emissions while travelling, in particular to do fewer but longer trips (p = 0.000), to buy locally and organically produced goods (p = 0.021), and to prefer eco-friendly accommodation (p = 0.048). With regard to age and level of education, no statistically significant differences could be found – the only exception refers to the energy-saving measures (e.g. turning off lights etc.), which are more popular for respondents being between 31 and 50 years old than for their younger and older counterparts (p = 0.001).

The surveyed tourists were further asked about the necessary framework conditions to go after a more eco-friendly tourism mobility (see Fig. 8.3). A large share of respondents, in particular females (p = 0.001–0.028) and persons being aged between 31 and 50 years (p = 0.002–0.030), expressed high levels of agreement (totally or rather agree) with regard to both the improvement of public transport (i.e. speed, comfort, tariffs) and more eco-friendly on-site mobility (i.e. rental bikes, e-cars). A sharing economy, be it classic car sharing or the possibility to rent out private cars while vacationing (and thereby earning some money), seems to be less favoured. However, respondents with higher education (p = 0.015) are more inclined to potentially do so.

Fig. 8.3. Tourists’ assessment of measures to promote more eco-/climate-friendly modes of transport (n = 470–489).

A lot of research has been done with regard to tourists’ (non-)reaction to climate change, particularly in the context of flying. Becken (2007), for example, concluded that tourists have very limited knowledge how air travel is affecting global climate change. Apart from that, little is known when it comes to tourists’ basic understanding of how climate change impacts tourism, and vice versa. Our survey shows that the winter tourists travelling to Alpbach-Seenland are fairly knowledgeable. On the one hand, it is generally believed that knowledge increases awareness and, subsequently, encourages behavioural change. On the other, there is a lot of scientific evidence that the existence or the provision of knowledge alone is not sufficient to trigger behavioural change. Without knowledge and a basic understanding, however, it is difficult to conceive why people should get involved in any change (Kollmuss and Agyeman, 2002).

The respondents consider transportation the most important contributor to climate change, followed by local activities and accommodation. This is in contrast to existing literature where accommodation is second. Preliminary, yet unpublished results from Alpbach indicate that travel to/from the destination (including day trips) is responsible for 54% of tourism’s total CO2e emissions, accommodation and gastronomy for 34% and activities for 12%. These figures differ markedly from the ones calculated for Whistler/Canada (Kelly and Williams, 2007). Moreover, in Alpbach it is not planes but cars that are responsible for the highest share of tourism transport’s emissions (Unger et al., 2016) and, similar to the work of Filimonau et al. (2014), there is a range of holiday settings (e.g. a group of three travelling from Berlin to Alpbach by car, coach or train and spending 5 nights there) where it is not travel to/from the destination but accommodation that contributes most to overall GHG emissions. This is not to downplay transportation’s role (in particular the role of international aviation), but to shed light on other contributors. Much of the public and scientific debate seems to concentrate on air travel. Again, from a global perspective, this is more than justified given the annual growth rates in international aviation. However, from a destination point of view, the same discussions are often taken as an excuse to do nothing, arguing that one cannot fight the trends in international aviation. Doing nothing, however, is not an option for a destination like Alpbach that welcomes tourists from relatively nearby source markets. Here, a switch from car to coach/train and more energy-efficient accommodation and gastronomy sectors relying on renewable energies could make a difference and markedly reduce the destination’s carbon footprint.

Speaking of measures to reduce energy consumption and GHG emissions in tourism, our findings confirm existing research. Most respondents are willing to pick the ‘low hanging fruits’ (i.e. use eco-friendly modes of transport for intra-destination mobility) but refuse ‘real’ changes in travel behaviour (i.e. travel less far and less often). The call for such changes is often perceived as a threat to the individual freedom to travel. There is a lot of evidence that people are unwilling to break with ‘dear’ habits (e.g. Becken, 2007; Hares et al., 2010; Higham et al., 2013). Cohen et al. (2013), summarizing much of the existing literature, identified two gaps: one between attitudes and behaviour, the other between the practices of home and away (see also Barr et al., 2010). People know that (air) travel is harmful but do not respond accordingly (e.g. Hibbert et al., 2013; Juvan and Dolnicar, 2014). This includes people who appear to be very committed to behaving in an environmentally friendly manner at home (Barr et al., 2010; Prillwitz and Barr, 2011). Dickinson et al. (2010) added the structures that exist within the travel industry that prevent people – feeling a lack of individual agency to act – from changing their travel habits. As a consequence, little can be expected from tourists in terms of voluntary changes in travel habits.

Eco-friendly on-site mobility is accepted (and wanted) by many tourists. A number of alpine destinations have continuously improved intra-destination mobility. Examples include ski buses, hiking buses and the extension of the existing public transport networks. In some cases, the offers are included in the ski passes and/or the accommodation packages (e.g. access to ski buses and local/regional transport networks), in other cases (e.g. hiking buses), extra must be paid for the services. Challenges include the set-up of these services as they usually have to satisfy both the needs of the locals (e.g. commuters and children going to school) and the tourists, and the financing of the respective services (e.g. Gronau, 2016; Scuttari et al., 2016). Our survey and observations in the destinations show that a lot of tourists (also those arriving by private car) are willing to use these services (and to ‘take a holiday from the car’) (Böhler et al., 2006). Moreover, an increasing number of people – at least in the European Alps – simply expect these services. Furthermore, a good intra-destination public transport network is often seen as a prerequisite for more eco-friendly travel to/from a destination. However, while such services are definitely important, they are probably not sufficient to induce larger-scale changes in travel to/from a destination.

With regard to travel to/from a destination, coach and train have continuously lost market share and struggle to compete with car and plane. Common arguments against more train travel for holiday purposes include time (e.g. duration of travel), price (e.g. in comparison to current flight tariffs), flexibility (e.g. dependent on schedules) and comfort (e.g. not door-to-door, luggage) (Böhler et al., 2006). A series of measures can help to make train travel more attractive: fast connections, shuttle services from railway station to destination and/or accommodation, luggage service from door-to-door, and attractive all-in packages. Again, improvements in public transport are possible and necessary but probably not sufficient to reach convinced car drivers who see in their vehicles much more than just a means of transportation.

Speaking of improvements: a large number of respondents indicated that they will choose energy-efficient accommodation relying on renewables in the future. However, the question remains: how much intention (will do in future) will translate into real behaviour? Preuss (1991, cited in Kollmuss and Agyeman, 2002, p. 250) distinguished between an ‘abstract willingness to act’ based on knowledge and values and a ‘concrete willingness to act’ based on habits. With regard to potential improvements in public transport: being perceived positively does not necessarily mean that people switch from car to coach and train.

There is an ongoing debate about emerging trends in car-based mobility. Apart from e-mobility, an increasing number of people, in particular young adults in urbanized areas, search for new types of mobility, i.e. a ‘decreased automobility . . . characterised by decreasing rates of licensing, vehicle kilometres travelled (VKT) and car ownership’ (Hopkins, 2016, p. 371). These changes will also affect travel to/from and within destinations. The respondents signalled interest in e-mobility but are reluctant when it comes to mobility concepts that are related to a sharing economy (see Fig. 8.3). However, much more detailed research is needed to link new types of mobility with tourism mobility. Furthermore, a change in ‘auto-mobility’ as outlined above does not necessarily mean a reduction in eco-unfriendly tourism mobility as the same people might be very eager to discover the world by plane.

Alpbach is not only a tourism destination but also a Climate and Energy Model region (www.klimafonds.gv.at). As such, the region is not only interested in but obliged to become more energy-efficient and climate-friendly. It is crucial that the tourism industry is part of this process. From a tourism point of view, the destination might focus on energy-efficient accommodation relying on renewable energies. This is one field where governmental support is available, and where tourists indicated that they are willing to prefer such accommodation in the future. Another topic is mobility. Local and tourism mobility are important components in every climate and energy assessment. The calculations by Unger et al. (2016) have shown that it is car travel (not air travel) that is responsible for most GHG emissions in Alpbach’s tourism. This calls for new mobility concepts: more public transport, but also new forms of auto-mobility (e-cars) and new types of mobility that challenge the current hegemony of private auto-mobility (e.g. sharing economy). So far, it is only an idea, but local policy makers and tourism managers are thinking about establishing an e-mobility park. In such a park, locals and tourists alike could test new forms of e-mobility. This hands-on experience will not change the world but, maybe, will have a bigger impact on people’s behaviour than well-intentioned advice.

Barr, S., Shaw, G., Coles, T. and Prillwitz, J. (2010) ‘A holiday is a holiday’: practicing sustainability, home and away. Journal of Transport Geography 18, 474–481. DOI:10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2009.08.007

Becken, S. (2002) Analysing international tourist flows to estimate energy use associated with air travel. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 10(2), 114–131. DOI:10.1080/0966958020866715

Becken, S. (2007) Tourists’ perception of international air travel’s impact on the global climate and potential climate change policies. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 15(4), 351–368. DOI:10.2167/jost710.0

Becken, S., Simmons, D. and Frampton, C. (2003) Energy use associated with different travel choices. Tourism Management 24, 267–277.

Böhler, S., Grischkat, S., Haustein, S. and Hunecke, M. (2006) Encouraging environmentally sustainable holiday travel. Transportation Research Part A 40, 652–670. DOI:10.1016/j.tra.2005.12.006

Chenoweth, J. (2009). Is tourism with a low impact on climate possible? Worldwide Hospitality and Tourism Themes 1(3), 274–287. DOI:10.1108/17554210910980611

Cohen, S.A. and Higham, J.E.S. (2011) Eyes wide shut? UK consumer perceptions on aviation climate impacts and travel decisions to New Zealand. Current Issues in Tourism 14(4), 323–335.

Cohen, S., Higham, J. and Reis, A. (2013) Sociological barriers to developing sustainable discretionary air travel behaviour. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 21(7), 982–998. DOI:10.1080/09669582.2013.809092

Dickinson, J., Robbins, D. and Lumsdon, L. (2010) Holiday travel discourses and climate change. Journal of Transport Geography 18, 482–489. DOI:10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2010.01.006

Filimonau, V., Dickinson, J. and Robbins, D. (2014) The carbon impact of short-haul tourism: a case study of UK travel to southern France using life cycle analysis. Journal of Cleaner Production 64, 628–638.

Forschungsgemeinschaft Urlaub und Reisen e.V. (2007) Akzeptanz klimaschonender Verhaltensweisen im Urlaub [Acceptance of climate-friendly behavior on holiday]. F.U.R., Kiel, Germany.

Gössling, S. (2010) Carbon management: mitigating tourism’s contribution to climate change. Routledge, London/New York.

Gössling, S., Scott, D. and Hall, C.M. (2015) Inter-market variability in CO2 emission-intensities in tourism: implications for destination marketing and carbon management. Tourism Management 46, 203–212.

Gronau, W. (2016) Encouraging behavioural change towards sustainable tourism: a German approach to free public transport for tourists. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 25(2), 265–275. DOI:10.1080/09669582.2016.1198357

Hares, A., Dickinson, J. and Wilkes, K. (2010) Climate change and the air travel decisions of UK tourists. Journal of Transport Geography 18(3), 466–473.

Hibbert, J.F., Dickinson, J.E., Gössling, S. and Curtin, S. (2013) Identity and tourism mobility: an exploration of the attitude–behaviour gap. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 21(7), 999–1016. DOI:10.1080/09669582.2013.826232

Higham, J.E.S., Cohen, S.A., Peeters, P. and Gössling, S. (2013) Psychological and behavioural approaches to understanding and governing sustainable mobility. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 21(7), 949–967. DOI:10.1080/09669582.2013.828733

Hopkins, D. (2016) Destabilising automobility? The emergent mobilities of generation Y. Ambio 46(3), 371–383. DOI:10.1007/s13280-016-0841-2

Juvan, E. and Dolnicar, S. (2014) The attitude-behaviour gap in sustainable tourism. Annals of Tourism Research 48, 76–95.

Kelly, J. and Williams, P.W. (2007) Modelling tourism destination energy consumption and greenhouse gas emissions: Whistler, British Columbia, Canada. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 15(1), 67–90. DOI:10.2167/jost609.0

Kollmuss, A. and Agyeman, J. (2002) Mind the gap: why do people act environmentally and what are the barriers to pro-environmental behavior? Environmental Education Research 8(3), 239–260. DOI:10.1080/1350462022014540 1

Kroesen, M. (2013) Exploring people’s viewpoints on air travel and climate change: understanding inconsistencies. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 21(2), 271–290. DOI:10.1080/09669582.2012.692686

Lassen, C. (2010) Environmentalist in business class: an analysis of air travel and environmental attitude. Transport Reviews 30(6), 733–751.

Lenzen, M., Sun, Y.-Y., Faturay, F., Ting, Y.-P., Geschke, A. and Malik, A. (2018) The carbon footprint of global tourism. Nature Climate Change 8, 522–528. DOI:10.1038/s41558-018-0141-x

Mair, J. (2011) Exploring air travellers’ voluntary carbon-offsetting behaviour. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 19(2), 215–230. DOI:10.1080/09669582.2010.517317

Manova (2014) T-Mona (Tourism Monitor Austria) – Visitor Survey Alpbach, Winter 2013/14. Österreich Werbung, Vienna.

McKercher, B., Prideaux, B., Cheung, C. and Law, R. (2010) Achieving voluntary reductions in the carbon footprint of tourism and climate change. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 18(3), 297–317.

Peeters, P. and Dubois, G. (2010) Tourism travel under climate change mitigation constraints. Journal of Transport Geography 18, 447–457. DOI:10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2009.09.003

Peeters, P. and Schouten, F. (2006) Reducing the ecological footprint of inbound tourism and transport to Amsterdam. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 14(2), 157–171.

Prillwitz, J. and Barr, S. (2011) Moving towards sustainability? Mobility styles, attitudes and individual travel behavior. Journal of Transport Geography 19, 1590–1600. DOI:10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2011.06.011

Rauch, F., Peck, S. and Ebner, V. (2010) Zusammenschluß der Skigebiete Alpbach und Wildschönau-Auffach – Verkehrsuntersuchung [Traffic assessment]. Internal report, Innsbruck, Austria.

Scuttari, A., Volgger, M. and Pechlaner, H. (2016) Transition management towards sustainable mobility in alpine destinations: realities and realpolitik in Italy’s South Tyrol region. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 24(3), 463–483. DOI 10.1080/09669582.2015.1136634

Unger, R., Abegg, B., Mailer, M. and Stampfl, P. (2016) Energy consumption and greenhouse gas emissions resulting from tourism travel in an alpine setting. Mountain Research and Development 36(4), 475–483. DOI:10.1659/MRD-JOURNAL-D-16-00058.1

UNWTO-UNEP-WMO (2008) Climate Change and Tourism: Responding to Global Challenges. UNWTO, Madrid, Spain.