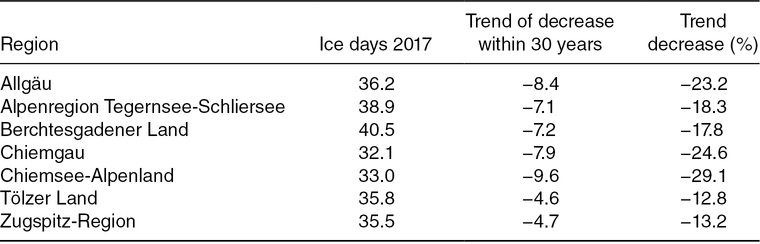

Table 9.1. Ice days in Germany. (Based on Potsdam Institut für Klimafolgenforschung [PIK], 2018.)

9 Climate Change Adaptation – A New Strategy for a Tourism Community: A Case from the Bavarian Alps

Competence Centre for Tourism and Mobility, Free University of Bozen-Bolzano, Bolzano, Italy

* E-mail: thomas.bausch@unibz.it

Based on the delimitation of the Alpine Convention (Alpine Convention Reference Guide, 2010) Germany has a share of about 6% of the alpine region. Thereby half of the German Alps take the form of foothills, while the other half rise up to altitudes mostly between 1000 and 2000 m. Only a few mountains reach a height of more than 2500 m. Compared with other alpine countries the highest summit, the Zugspitze with an altitude of 2964 m, is not extremely high. Furthermore, the level of the settlement areas of most of the tourist centres, for example, Berchtesgaden, Reith im Winkel, Garmisch-Partenkirchen or Oberstdorf, is usually not above 1000 m. Often the relatively flat and wide valley bottoms are located at only 750 m or below. Furthermore, many of the inner alpine mountains are very rocky or the hillsides are covered with steep mountain forest. Considering this topography, the potential for winter sport resorts is very limited compared with other alpine regions. The largest skiing area, the Steinplatte/Winkmoosalm in Reith im Winkl, encompasses slopes with a total length of 42 km, followed by the classic skiing area of Garmisch-Partenkirchen with 40 km (statistics from Skigebiet.de, 2018). In most other skiing areas, the slope network is no more than 20–30 km.

Therefore, the German winter sports resorts in some respects are not competitive on the alpine ski holiday market. For advanced and more athletic skiers, the skiing areas are much too small. Even though they are small, they are often too challenging for beginners and intermediate skiers. Nevertheless, all the skiing areas are very attractive for day trippers as well as short stay guests. The large metropolitan area of Munich with about 2.5 million inhabitants is only 100–150 km away from most Bavarian skiing areas and therefore plays an important role on the day trip market. During winter weekends ski enthusiasts regularly make use of the facilities on 1-day skiing excursions. The regional railway companies cover this demand by offering packages combining the railway ticket and an all-day ski-pass.

As most winter holiday areas in Bavaria are competitively limited compared with the large ski areas in Austria, France, Italy and Switzerland, especially on the 1-week skiing vacation market, the product has developed into a multi-recreational winter holiday option: taking walks in a winter wonderland, visiting cosy mountain huts with typical regional dishes, doing some sports like cross-country skiing, alpine skiing, sledging or ice-skating, taking a cable car up a mountain and sitting in the sun, enjoying spa and wellness facilities or visiting cultural or sports events. Within this setting, smaller ski areas play an important role as part of a multi-optional product – in the case of sunny weather and nice snow conditions some of the guests might want to choose the option of skiing and visiting the mountain huts in the ski area for 1–2 days. This is the segment of winter tourists who do not ski every day and who require multi-optional products from which they can chose various options day by day.

Due to the low altitude of Germany’s alpine destinations they are highly affected by climate change. In winter the number of ice days, which are days with a highest temperature not above 0°Celsius, will decline in the next 30 years by 12% to nearly 30% (Potsdam Institut für Klimafolgenforschung [PIK], 2018) (see Table 9.1).

Not only will the ice days decrease – all other snow security-relevant parameters are already showing a significant decline compared with the past 30 years: the first date in autumn with frost, the date of the first 3-day ice period, which is important for artificial snow production, the date of the first natural snowfall, the number of frost days (days with at least one temperature below zero), the amount of natural snowfall and the number of days with natural snow coverage (Bausch et al., 2017a). This leads to a change in the perception of snow security, but also in the general quality of winter holidays in German alpine destinations for skiers (Berghammer and Schmude, 2014). Therefore, climate change has a strong impact on the general framework conditions of the winter product in these tourism regions. Even though in Germany skiing is only a part of the multi-optional product, the guests nevertheless expect a snow-covered landscape with a real winter atmosphere as the central element of their holidays.

Furthermore, other factors have changed the winter tourism market. First of all, there is the huge volume of warm winter destinations easy to reach by plane and available for a reasonable price. The Canaries, Caribbean, Maldives, Middle East and Persian Gulf, Red Sea region, South Africa, Seychelles, Thailand and Vietnam are attractive and popular winter destinations. In the past 10 years the prices of long-haul flights have decreased, meaning that these destinations can be reached at low cost, yet still enjoy high prestige. Second, the cruise ship sector has developed over the past 20 years very dynamically. While in 1995 only 309,000 German passengers went on cruise holidays, in 2017 the number increased to 2.7 million, which is a growth of 870% (Deutscher Reiseverband e.V., 2019). The fleet of cruise ships and their capacity for travel all year round grew globally in the same way. In the years 2014 to 2017 globally about 27 large new cruise ships with 76,000 new berths and a total capacity of ~24 million overnight stays entered the market (Bosneagu et al., 2015). This continuous growth put enormous pressure on the ship-owning companies to sell these capacities not only in the summer but all year round. Reasonably priced packages entered the market using all available distribution channels and professionally promoted by targeted communication campaigns. As a third factor demographic change has to be mentioned. More and more skiers from the baby boom generation are reaching an age at which physical and health conditions reduce sports activities and, therefore, also winter sports. On the other hand, today, in German families, children do not learn skiing automatically anymore. The reasons for this reduced number of winter sports beginners are manifold: the lack of snow in the mid-range mountains, skiing is not part of school sports anymore, skiing is only rarely part of sports reporting in the programmes of the large TV channels, but also the costs of ski holidays are too high for many middle-class families.

These changed framework conditions have forced winter destinations in the German Alps, but also in other traditional winter holiday regions, to innovate and adapt their products, as otherwise they would enter into the decline phase of the tourist area life cycle (Butler, 2006). Therefore, climate change is one among several factors necessitating adaptation.

Mittenwald is a traditional touristically developed alpine village in the district of Garmisch-Partenkirchen to the south of Munich on the border with Austria. The village is located at an altitude of 850 m in the upper valley of the river Isar and surrounded by the massifs of the Karwendel, the Wetterstein and Ester. Together with its two neighbouring villages, Krün and Wallgau, they form the destination known as Alpenwelt Karwendel with about 1.4 million overnight stays and 400,000 guest arrivals annually. Furthermore at least 1.2 million day trip visitors make an excursion to the destination every year, as it can be reached easily by car, train and long-haul buses, making access fast and easy compared with the central alpine areas.

The wide and relatively flat bottom of the valley provides perfect conditions for hiking and cycling in summer as well as cross-country skiing in winter. Several lakes with smaller public bathing beaches provide options for swimming and relaxing in summer. These elements are embedded in a cultural landscape of outstanding quality as well as pure alpine natural scenery formed by the three massifs with several summits above 2000 m as well as by the river Isar, which in most sections of the valley still has the character of a torrential stream. In the north-western part of the village of Mittenwald a mid-range mountain, the Hoher Kranzberg, nestles as a kind of foothill to the Wetterstein massif. With just one single funicular travelling up to the western Karwendelspitz, this is the only touristically developed area within a largely still untouched alpine landscape. One chairlift (all-year) and six cable car lifts (only winter) provide transport up to several typical mountain huts, enabling visitors to go hiking as well as in winter to ski. Therefore, this mountain is a central supply component as an experience and recreation area for guests expecting an unforgettable stay in the Upper Bavarian Alps.

While larger ski resorts in the neighbouring region of Tyrol have shown a yearly stable increase of guests, overnight stays and day trip visitors in the winter season, the Alpenwelt Karwendel destination and especially the village of Mittenwald have been faced with a constant decrease. While in commercial accommodation (establishments with ten or more beds) in 2006 about 73,500 overnight stays were counted in Mittenwald between November and March, in the years 2015 to 2017 the level declined to volumes around 57,500 (Landesamt für Statistik Bayern, 2018). This decline in winter could not be compensated by the summer season, which for years has remained at a stable but not growing level. The number of commercial accommodation establishments decreased within 10 years from 74 to 51, which is a loss of nearly one-third. This crisis in tourism led to a shrinking of the local economy in general: restaurants, retailers, sport and event agencies, the real estate market as well as the local building business. As the village has a remote location in the south of Upper Bavaria a transition of the economic system from tourism to other business sectors is not a realistic option. Therefore, the municipality council mandated the mayor and the destination management to submit a proposal to adapt and innovate the infrastructure and related services at the Hoher Kranzberg as a central element of the tourism product.

SWOT analysis is a well-established method in the field of regional as well as destination development (Veser, 2014). First, a list of strengths and weaknesses (SW) of the current tourism system was set up by a local working group consisting of some members of the destination management organization (DMO), the head of the cable car company and four external experts from tourism and infrastructure planning. The SWs they found were then analysed by concentrating on a few mega trends: climate change, demographic change, expectation for experience raising, individualization and digitalization. Each strength and each weakness was analysed in light of each mega trend and their future development and related opportunities or threats (OT) derived.

In general, the area of the Hoher Kranzberg is an example of outstanding nature and scenery created by human cultivation over many centuries, especially its meadows with a surface dotted with humps, the so-called Buckelwiesen. These meadows stand out with their incomparable richness of diversity of alpine flora and related fauna, especially butterflies and dragonflies. Therefore, more than 60% of the area is protected under the Council Directive 92/43/EEC on the conservation of natural habitats and of wild fauna and flora, a so-called Natura2000 reserve (Pröbstl-Haider and Dorsch, 2016). In addition, a large number of protected biotopes are officially mapped and part of the Bavarian biotope mapping of the Alps. On the one hand, this underlines the potential of unspoiled nature as part of the unique selling proposition for visitors in that area. On the other, it obviously sets very strict limitations for adaptation measures, which in any case would require at least small interventions in the natural structure. Furthermore the impacts of additional tourist attractions to the natural environment which might be caused by a higher visitor pressure and the sporting activities of these visitors must be anticipated and weighed up (Pröbstl-Haider and Pütz, 2016).

Concerning winter tourism, climate change was a key field of discussion in the SWOT analysis. As the area of Hoher Kranzberg is located at an altitude between 850 m in the valley and only 1397 m at the summit it is already being affected by climate change today. Analysing the series of weather data between 1985 and 2015 it becomes apparent that all the parameters linked to natural snow security, but also linked to required conditions for artificial snowmaking, have degraded heavily. The number of ice days, which are days with 24 h at a temperature below 0°Celsius, decreased for the period first of November to the end of March from mostly between 40 and 30 days in the past century to often below 10 in the past decade. The first ice day shifted from usually mid or end of November to the end of December; sometimes it did not happen until January. The number of periods with 3 consecutive ice days, which are needed as good conditions for artificial snowmaking, decreased from three to four periods to only one. The maximum number of consecutive ice days in November and December also shrank from usually 10–12 to now 3–5. As the daily average temperature also increased by about 1–1.5°Celsius, rain instead of snow as precipitation can be frequently observed these days during the winter period.

The following climate change-related opportunities and threats were identified:

• Declining average number of days with natural snow coverage in the valley.

• Reduced snow security for cross-country skiing and winter hiking in a snow-covered landscape.

• Shift of first period with minimum 3 consecutive ice days to end of the year/beginning of new year, leading to a need for improvement of the capacity of the artificial snowmaking facilities with higher capacity to allow basic snow coverage of 30–50 cm within 3 days.

• Declining average number of days with good to very good skiing conditions from 100 to 80 in combination with later start of the skiing season.

• Longer late autumn periods with relatively warm and sunny weather and good conditions for hiking and mountain biking – more often until the beginning or middle of December.

• Currently existing natural sledge run in future only usable for a very small number of days – need for relocation to the north side of the mountain near to the slopes with snowmaking facilities.

• Because of the wide and flat topography of the Kanzberg summit there is an opportunity to create a winter hiking round trip on the top with long snow security in combination with a large number of days with sun.

A further factor considered by the SWOT analysis was demographic change. The main findings here were in general opportunities coming along with barrier-free access for elderly or handicapped guests as well as families with small children transported in baby buggies or in winter on childsledges. In winter in addition a modern and competitive beginner’s area at the valley station offering not only skiing lessons, but also a snow playground for non-skiing children, was judged as a further opportunity.

In general, the discussion of the current strengths and weaknesses and anticipated related opportunities and threats leads to a revision of the former strategy. While in the past the future development of the area of Hoher Kranzberg was always only seen from the perspective of the winter season and alpine skiing, now the approach has widened. First, not only the winter but also the summer are seen as seasons of equal importance. Second, in summer the outstanding unspoiled nature and scenery were moved to the centre of the future product development. While many competitors in the neighbourhood focus on sports and action-oriented, hard tourism development approaches, the positioning of Hoher Kranzberg has moved exactly in the opposite direction: an area for calm, slow and nature-based tourism offering the guests an insight into and experiences from the natural alpine environment. In winter the focus was also changed. To underline the approach of nature-based tourism it was decided not to enlarge the range of slopes with artificial snow. Only those already equipped in the past with snow guns became part of the adaptation. All other slopes were kept as natural snow skiing areas, which were operated only during those periods where natural snow precipitation offered a minimum snow cover of 20–30 cm. In addition, new products were to offer non-skiers genuine alpine winter experiences during the winter season. This is a further new positioning element of the destination, which addresses a market that is not interesting for many competitors with large ski resorts. The target is to increase the share of winter guests from the non-skier segment.

The general strategy decisions were concretized for nine tourist groups:

1. All-season groups:

a. Real mountain hut experiences with authentic Bavarian cosiness.

b. Mountain experiences for the handicapped.

c. Hoher Kranzberg as an area for all-day activities in pure natural surroundings.

2. Winter guests:

a. The enjoyment of the natural environment – ‘slow motion’ in winter landscapes.

b. The exploration of the natural environment – detecting and understanding the mysteries of winter nature.

c. Family and kids snow fun (0–10 years, parents and grandparents).

3. Summer (including late spring and autumn) guests:

a. Alpine natural experience for families and kids (0–10 years, parents and grandparents).

b. Culture and landscape in the alpine space of Upper Bavaria.

c. The enjoyment of the natural environment – ‘slow motion’ in the summer mountain world.

For each of the listed nine guest groups a product development project was launched. The status of the infrastructure was ascertained by means of a concrete mapping and evaluation of the status quo of the existing attractions, their location and accessibility and the currently available services. By comparing the status quo and the envisaged future ideal product, a list of development measures and the required stakeholders was drawn up. Finally, all the infrastructure in the area was assessed concerning its current status and the future requirements needed to fulfil the function for the nine guest groups. In this step again, especially for the winter season, climate change scenarios were considered when an adaptation of existing infrastructure was rated as necessary.

Of course, a central concern of the adaptation discussion was the existing and partially obsolete winter tourism infrastructure. A one-seat chair lift, which originally was installed in 1950 and partially adapted in 1973, obviously had to be rated as no longer viable, as well as the fact that the cable lifts are nowhere near the standards adhered to by the competitors in the neighbouring destinations. The small cabin cable car connecting the end station of the chair lift halfway up the mountain with the summit has been out of order for several years. Therefore, the summit cannot be reached by non-skiers via cable car. The beginner’s area is currently crossed by one of the main slopes, creating conflicts and risk of accidents. The capacity of the artificial snowmaking facilities is insufficient to produce the needed amount of snow within 3 days of good snowmaking conditions. The toboggan run, partially located on the south side, is separated from the ski run areas and therefore cannot use the artificial snowmaking facilities of the slopes. This means that it is only available for a few winter days when there is sufficient natural snow cover. The parking near the valley station also does not adhere to modern standards – the public buses have problems parking and turning and this is not possible near the valley station. This systematic analysis contrasting the demand of each of the nine groups above with the current infrastructure showed very clearly that the only solution resolving the long list of deficits would be a new two-section detachable cable car lift, each detachable cabin with 12 seats and enough space for wheelchairs or child buggies. The old chair lift, an old and longer cable lift, as well as the summit cabin cable car, are to be dismantled to make way for the construction of the new lift.

The options for the location of the technical buildings of the cable car lift in the valley, the halfway station and the summit station were very limited as the old infrastructure, constructed back in the 1960s and 1970s, was partially located in the Natura2000 reserve. The same problem arose with the routes of the roads and car parking facilities in the valley. In a close dialogue with the nature protection and conservation authorities of the district, the region and the federal state of Bavaria, a solution was found that, on the one hand, embraces the regulative framework of national and European environmental legislation, and, on the other, fulfils the needs of the guests and offers further development options in future within the framework of the tourism strategy.

The most challenging and sensitive elements of the adaptation concept concerning the resolving of potential conflicts with protected nature elements, local property owners or potential criticisms from the public and NGOs were:

• The new route of the two-section detachable cable car lift, especially the location of the three stations and its ropeway pylons, avoiding forest clearance or intervention in highly sensitive biotopes.

• The route of the new round hiking trail at the summit, offering, on the one hand, spectacular views of the surrounding mountain massifs and the alpine natural environment but, on the other, avoiding the disturbance of sensitive and endangered species, especially the grouse in this area.

• The innovation of the artificial snowmaking facilities, especially the provision of a larger water buffer repository without the creation of an artificial pond as well as the hauling traces for the new water pump pipes.

• The relocation of the toboggan run, which in future is to connect the halfway station with the valley, on a route that does not cross slopes, hiking trails or connecting paths to mountain huts.

A multi-stage planning process was selected to find for each element a solution that considers the ecological constraints, technical needs and the functional objectives for the future guest groups. In a first step based on field walking and existing mappings of biotopes, several alternatives for the route and stations were developed. These alternatives were assessed by an external expert concerning their impacts on biotopes or nearby sensitive areas as well as future potential visitor pressure. Based on this expertise, a revision of the alternatives took place until a final best suitable proposal was found. This proposal was then presented to and discussed with the regional nature conservation and protection authority, which finally made several suggestions on the need for further improvements or the possibility of potential minor conflicts – all with the aim of finding detailed solutions. In a further step the owners of the land where building measures or future touristic activities are to take place were informed and agreement was secured. Finally, a presentation of the best suitable solutions took place in a confidential municipality council meeting. This led to an iterative process in which a proposal was developed that, in general, could be rated as ready for detailed planning and later approval (Bausch et al., 2017b).

Climate change adaptation, as with all kinds of adaptation processes of community relevant infrastructure or services, can be steered between two opposite approaches: top-down or bottom-up. Several publications (Lidskog and Elander, 2009; Amaru and Chhetri, 2013) argue that only by the bottom-up approach can a long-term local resilience of the adaptation measures be reached, as only early participation will guarantee a high level of acceptance of the finally proposed adaptation strategy. These publications therefore suggest starting adaptation from the very beginning on the basis of broad participation of all kinds of stakeholders and interest groups, not only informing them about objectives and the status of the adaptation plans, but also offering them the opportunity to propose further adaptation measures and to take the decision making (Müller et al., 2014) on the final adaptation strategy.

The present case did not follow a bottom-up approach as recommended in many publications. This was a conscious decision after having analysed the history of the former discussion, the local governance structure as well as the general debate about skiing facility adaptation measures in Bavaria in the year 2016. In 1999 a first attempt had already been made to renovate the existing lift and cable car infrastructure in the Hoher Kranzberg area. The municipality council at that time commissioned an engineering expertise project that only considered the question of winter sports and the needs of the tourism stakeholders in the area as well as the village of Mittenwald. This was a mixed process of a top-down approach by the municipality council, but also with low-level participation of the tourism sector. The resulting plan was presented and discussed in a public meeting of the municipality council and became an object of general public debate. This plan was never able to be implemented as during the planning process one group of stakeholders was never informed and asked for their agreement, i.e. the owners of the plots of land needed for adaptation in the area. They blocked all further development as they felt they had been ignored. The fact that other people discussed what was to happen with their property without asking them was unacceptable from their perspective. Their understanding was that they must be involved as owners and must agree before a general public debate can be opened.

A further reason for a confidential planning process was the general political atmosphere concerning skiing area adaptations in Bavaria. In the 1970s and 1980s the very dynamic development of the tourist infrastructure in the Bavarian Alps ignited the fear that the natural environment of the mountains would be irretrievably destroyed. This led to the government adopting a protected areas zoning plan for the Bavarian Alps that declared large parts of the mountains as areas excluded from any further development. Furthermore, the clearing of mountain forest areas larger than 1 ha in general was prohibited by a decision of the Bavarian parliament. With the signature of the Alpine Convention, as well as the nomination of many parts of the Alps as Natura2000 protected areas, the share of protected areas was increased in the 1990s. Later in the first decade of the new century more and more local policy makers, cable car companies and destination managers intervened to abolish the protection measures or at least to allow exceptions to be made. This provoked a backlash from the environmental NGOs. The first exceptions for the necessary adaptations for the 2011 FIS world championships held in Garmisch-Partenkirchen opened the door for more and more projects, each in itself not very large, but in total a gradual undermining of the existing legislation. A point of culmination was the attempt to construct a new cable car installation as well as a new slope at the Riedberger Horn in the western Bavarian Alps, which led to a public debate, both national as well as international, on the conflict brought about by the innovation of skiing resorts and the protection of the alpine natural environment in Bavaria. The project in Mittenwald had just started when the general debate was in full swing. It was very likely at this point that an open public discussion about a new cable car at the Hoher Kranzberg would be interpreted as the next case of protecting the sensitive alpine natural habitat. Subsequently the environmental NGOs wanted to move the discussion from the very beginning from the local to the state level. This was a further reason to desist from a public participation at the beginning of the planning process.

The present case of climate change adaptation in the area of Hoher Kranzberg underlines that adaptation processes can never be seen only from the perspective of one single factor. Climate change is an issue forcing many alpine regions to develop adaptation strategies to stay competitive or to re-establish themselves as competitive. An adaptation strategy, however, must always consider further relevant mega trends and factors changing the framework conditions of the tourism system as well as related changes in the market. The change in winter travel behaviour of consumers must be considered, but so too must changed expectations and preferences in the summer season be included in the strategy. Second, the change in the competition as a result of new destinations, products and distribution channels cannot be ignored. Factors such as demographic change, global cheap transport or digitalization in many cases can play a more important role than climate change. Therefore, a solid SWOT analysis as the basis for adaptation strategy development is essential.

Concerning the planning process, the literature also promotes bottom-up and participatory processes, embracing the history, culture of the area and the general public debate. Stakeholder groups with a strategic key role and personal concerns for their property – groups that are able to block a process – should always be involved before a public debate is opened. Iterative planning, involving the necessary expertise in each round of the improvement talks, leads to both a suitable and, in this case, sustainable result. Putting sustainability at the centre of the future positioning of the destination and the further development of Hoher Kranzberg as a key feature of guest attractions created a holistic perspective during the planning. Furthermore, the dialogue at an early stage with the nature conservation authorities that are later responsible for the approval of construction permits helps to detect hidden obstacles at an early stage.

Alpine Convention Reference Guide (2010) Alpine Signals 1st–2nd edition. Permanent Secretariat of the Alpine Convention, Innsbruck/Bolzano, Austria/Italy. Available at: www.alpconv.org/en/publications/alpine/Documents/AS1_EN.pdf (accessed 29 January 2019).

Amaru, S. and Chhetri, N.B. (2013) Climate adaptation: institutional response to environmental constraints, and the need for increased flexibility, participation, and integration of approaches. Applied Geography 39, 128–139. DOI:10.1016/j.apgeog.2012.12.006

Bausch, T., Ludwigs, R. and Meier, S. (2017a) Winter tourism and climate change – impacts and adaptation strategies. Munich University of Applied Sciences, Department of Tourism. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/313892568_Winter_Tourism_and_Climate_Change_-_Impacts_and_adaptation_strategies (accessed 5 March 2017).

Bausch, T., Koziol, K., Ludwigs, R. et al. (2017b) Prozessgestaltung und Steuerung von Klimawandelanpassung in kleinen bayerischen Gemeinden (TUF01UF-66836) Teilprojekt Mittenwald. Abschlussbericht. Munich/Axams: Hochschule Munich, Fakultät für Tourismus in Zusammenarbeit mit Klenkhart & Partner Consulting ZT GmbH.

Berghammer, A. and Schmude, J. (2014) The Christmas–Easter shift: simulating alpine ski resorts’ future development under climate change conditions using the parameter ‘optimal ski day’. Tourism Economics 20(2), 323–336. DOI:10.5367/te.2013.0272

Bosneagu, R., Coca, C.E. and Sorescu, F. (2015) Management and Marketing elements in maritime cruises industry. European cruise market. EIRP Proceedings 10(0). Available at: www.proceedings.univ-danubius.ro/index.php/eirp/article/view/1621 (accessed 26 July 2018).

Butler, R.W. (ed.) (2006) The Tourism Area Life Cycle . Aspects of Tourism 28. Channel View Publications, Clevedon, UK.

Deutscher Reiseverband e.V. (2018) Der Deutsche Reisemarkt. Zahlen und Fakten 2018. Available at: https://www.drv.de/fachthemen/statistik-und-marktforschung/detail/reisemarkt-2018-zahlen-und-fakten-liegen-in-neuer-auflage-vor.html (accessed 17 July 2019).

Landesamt für Statistik Bayern (2018) Official tourism statistics Bavaria: establishments, beds, arrivals and overnight stays in commercial establishments. Genesis Online Datenbank, Monatserhebungen im Tourismus. Available at: https://www.statistikdaten.bayern.de/genesis/online/data?operation=statistikAbruftabellen&levelindex=0&levelid=1534507812057&index=2 (accessed 29 January 2019).

Lidskog, R. and Elander, I. (2009) Addressing climate change democratically. Multi-level governance, transnational networks and governmental structures. Sustainable Development 18(1), 32–41. DOI:10.1002/sd.395

Müller, E., Durrer Eggerschwiler, B. and Stotten, R. (2014) Awareness rising for demographic change: the need for a participatory approach. In: Bausch, T., Koch, M. and Veser, A. (eds) Coping with Demographic Change in the Alpine Regions – Actions and Strategies for Spatial and Regional Development. Springer, Berlin, pp. 37–42.

Potsdam Institut für Klimafolgenforschung (PIK) (2018) Klima in den Deutschen Tourismusregionen: 1961–2017. Karten und Tabellen zu dem Klimawandel in Deutschen Reisegebieten. Available at: www.pik-potsdam.de/~peterh/tourismus/tourismus.html (accessed 29 January 2019).

Pröbstl-Haider, U. and Dorsch, C. (2016) Verträglichkeitsuntersuchung für das Erholungs- und Bergerlebnisgebiet Kranzberg, Markt Mittenwald. Arbeitsgruppe für Landnutzungsplanung Institut für ökologische Forschung, Etting-Polling, Germany.

Pröbstl-Haider, U. and Pütz, M. (2016) Großschutzgebiete und Tourismus in den Alpen im Zeichen des Klimawandels. Natur und Landschaft 91(1), 15–19. DOI:10.17433/1.2016.50153375.15-19

Skigebiet.de (2018) Skigebiete – Ranking nach Länge der Piste in Deutschland 2017 Statistik. Available at: https://de.statista.com/statistik/daten/studie/320631/umfrage/skigebiete-anzahl-in-ausgewaehlten-europaeischen-laendern (accessed 17 August 2018).

Veser, A. (2014) Regional SWOT analyses for demographic change issues: tools and experiences. In: Bausch, T. et al. (eds) Coping with Demographic Change in the Alpine Regions. Springer, Berlin, pp. 29–36.