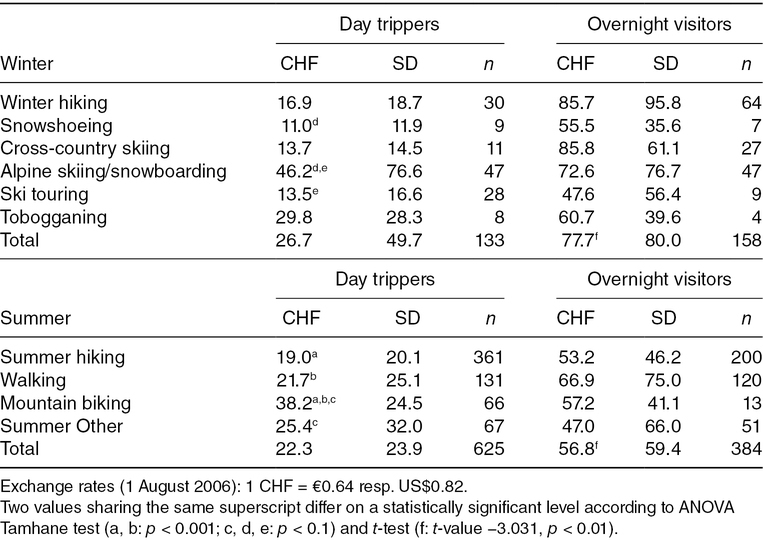

Table 10.1. Mean daily expenditure per person of visitors to Simmental and Diemtigtal in 2005/06 differentiated by main activities. (Own calculations, data based on Mayer et al., 2009.)

10 Economic Relevance of Different Winter Sport Activities Based on Expenditure Behaviour

1Universität Greifswald, Greifswald, Germany; 2Julius-Maximilians-Universität Würzburg, Würzburg, Germany

* E-mail: marius.mayer@uni-greifswald.de

The economic importance of winter and ski tourism for regional economic development is often used as an argument in favour of infrastructure development in land use planning decisions or when administrative authorizations are needed (Seilbahn.net, 2016; Bundesverwaltungsgericht Republik Österreich, 2018). This is especially relevant as winter and ski tourism activities face considerable challenges: impacts of global warming could reduce the snow-reliability in the future even when artificial snow is taken into account (Soboll et al., 2012; Steiger et al., 2019), while at the same time less snow-dependent alternatives are promoted by environmentalists (CIPRA, 2017) even though their economic viability has yet to be proven (Siegrist and Gessner, 2011). Kleissner (2012, p. 19) even concludes: ‘There is no economic alternative to winter sports!’ Therefore, it is crucial to assess the economic importance of different winter sport activities to address the following questions:

• What are the differences in the expenditure behaviour between winter tourists and visitors during the rest of the year (mainly the summer season)?

• What are the potential losses if winter sport activities eventually become impossible due to climate change-induced lack of snow?

• Which economic impact of winter sport activities can be maintained by technical adaptation measures to climate change like snowmaking or snow farming?

• Which opportunity costs of ski tourism need to be covered if less infrastructure-intensive activities should be promoted (e.g. in a protected area setting)?

• How much does the economic relevance of several winter sport activities vary (e.g. alpine skiing, cross-country skiing, winter hiking/walking, ski touring, snowshoe walking, tobogganing)?

This chapter addresses the economic relevance of winter tourism based on two case studies in Switzerland and Germany which provide the opportunity to compare the expenditure behaviour and economic impact of different segments of winter tourists from alpine skiers on groomed slopes to eco-tourist snowshoe hikers. Both studies also allow comparisons with the spending behaviour of non-winter tourists.

The main drivers of the economic impact/benefits of tourism are the frequentation, expenditure patterns and the economic structure of the destination/region. The local economy determines the multiplier effect of tourism by the share of leakages and the amount of money spent there again for investments and daily living by businesses and tourism staff alike (Mayer and Vogt, 2016a). This illustrates the central role of spending for the analysis of the economic relevance of tourism, which has been recognized by a number of studies in the past 15 years (see Brida and Scuderi, 2013 and Mayer and Vogt, 2016a for recent overviews).

In the following, we provide a short overview of existing studies on the expenditures of winter tourists and identify research gaps. Even though many publications about mountain and winter tourism in general depict winter tourism as generating more economic impact due to higher spending (Leitner, 1984; Jülg, 2007; StMWIVT, 2007; Feichtner, 2017), there are surprisingly few peer-reviewed studies providing empirical evidence. The problem seems to be a general lack of comparative expenditure and/or economic impact studies for winter and summer activities based on the same base population or the same destinations. For instance, MANOVA (2016) undertook a compelling economic impact analysis of the Austrian cable car and ski lift industry including the visitor spending but there is no counterpart for the summer season. The German Cable Car Association also published an economic impact analysis but does not differentiate between winter and summer season (VDS, 2015).

For Austria, where the economic relevance of winter tourism is widely acknowledged (Kleissner, 2012; Feichtner, 2017), representative market research data are available for 2013/14 differing between the seasons: excluding transport to the destinations, winter tourists on average spend €120.0 per person and day, compared with €98.0 in the summer (+29.6%). The most important differences in absolute terms stem from the expenditure on transport in the destination (winter €21.0 vs. summer €5.0), most likely for lift tickets as well as in the amount of money spent on accommodation (winter €54.0 vs. summer €45.0, +20%) (own calculations based on WKO, 2018).

In Switzerland, BAK Basel (2012) refers to the representative ‘Tourism monitor Switzerland’ from 2010, which reveals that the share of high-spending guests in the winter season is considerably higher compared with the summer: 27.2% spend more than CHF250 per day in winter, in summer only 17%. Conversely, 22% of winter guests spend less than CHF100 per day, in contrast to 36.2% in the summer. Also in Switzerland, several economic impact studies allow calculations of a winter–summer expenditure gap: in Berner Oberland (10.3%), Valais (9.5%), Engelberg (10.2%) and Nidwalden (10.2%) overnight guests spend more in winter than in summer, while day trippers spend more in summer in both Berner Oberland (1.9%) and Valais (4.3%) and more in winter in Engelberg (15.4%) and Nidwalden (6.4%) (Rütter et al., 1995, 2001, 2004).

A shortcoming of many international studies is the focus on just one winter sport activity, resulting in a lack of comparisons with other alternatives. If leisure activities are differentiated, then the methodological problem arises as to which activities are clearly winter-related. Hiking and walking, as well as hunting, nature observation, driving or fishing could technically be done all year around. The study by Mehmetoglu (2007) is an example with rather vaguely defined activity groups: it is unclear whether his ‘challenging nature-based activities’ refer to winter or summer activities. Nevertheless, on the international level the following studies provide some indications about the expenditure patterns of winter activities.

Pouta et al. (2006) found out that nature trips related to cross-country skiing in Finland were more likely to be high-expenditure trips than trips taken for other purposes, while backpacking, in contrast, was more often related to low-expenditure trips. The availability of alpine skiing facilities was related to higher-expenditure trips.

Fredman (2008) shows that alpine skiers in the Swedish mountains spend on average 3.1 times more per trip in the destination compared with backpackers and even 1.5 times more than snowmobilers.

White and Stynes’ (2008) detailed study about spending patterns of different outdoor recreation activities best allows differentiation between winter and summer seasons. Three out of five activity segments showing statistically significant higher per trip expenditures in US National Forests are winter activities (alpine and cross-country skiing, snowmobiling), while hiking/biking is related to significantly lower spending compared with the overall average. The authors stress that it is crucial to analyse the spending of visitors differentiated by trip type (e.g. day trippers vs. overnight visitors) because this ‘can mask important differences in the spending of visitors engaged in the activity but participating in different types of recreation trips’ (p. 21). Non-local alpine skiing day trippers for instance spend 117% more per trip than hikers/bikers, while for non-local overnight visitors the deviation between both activities still reaches 39.2%.

If one compiles the total average per party per trip spending of the 12 recreation activity groups reported by White (2017) for the US National Forest 2010–2015 expenditure data, rank them in descending order for the four visitor types (non-local and local day trippers, non-local and local overnight visitors) and averages the ranks, it is evident that explicit winter activities (alpine and cross-country skiing, snowshoeing, snowmobiling) reach the best average rank places (2.8), while activities neither attributed solely to winter nor summer reach 6.5 and explicit summer activities rank lowest (10.1). Snowmobiling and alpine skiing/snowboarding achieve the highest expenditure averages for all visitor types, while cross-country skiing/snowshoeing ranks seventh for the day trips and fourth for overnight trips. Alpine skiers spend between 98.5 and 146.9% more than hikers (for day trips), respectively, 52.1–86.6% more per overnight trip. For cross-country skiers the deviations vary from 22.8–50.0% for day trips and from 19.4–46.4% for overnight visits. Thus, White’s (2017) results provide further evidence for the higher spending of winter tourists.

The following reasons are given for the higher spending in the winter season (Leitner, 1984; Jülg, 2007):

• Operating costs in winter are higher, especially for energy due to heating and electricity needs of lighting, cable car, ski lifts and snowmaking facilities.

• Winter guests are to some extent more affluent than summer guests and must be able to afford the higher prices for accommodation 1 (partly due to higher costs, partly due to the higher demand with fewer substitution possibilities in the winter season) and equipment.

• Alpine skiers must buy lift passes, which cost more than €50 per day in the biggest and most prominent resorts. In addition, ski school fees have to be paid for children, other beginners or to improve technique.

• The relatively short daylight time leads to long evenings motivating additional spending for food, drinks and entertainment (‘après ski’).

Finally, the high importance of spending notwithstanding, we must consider also the frequentation in winter and other seasons and the length of stay. Especially in the high mountain regions of the Central Alps more overnight stays are recorded in winter than in summer (Mayer et al., 2011). Evidence from Austria shows that winter guests (in regions with strong ski tourism) stay longer on average (4.5 nights in winter vs. 3.6 nights in summer for Tyrol in 2017; 4.23 vs. 3.45 Salzburg 2015/16; 4.17 vs. 3.24 Vorarlberg 2015/16) (Statistik Austria, 2016; Amt der Tiroler Landesregierung, 2017), which additionally increases the importance of the winter season.

Despite not being representative for winter tourism in all its variations of course, both case studies in sections 10.3 and 10.4 share the advantage of featuring comparable methodologies for several winter as well as summer activities sampled in the same survey areas thus providing unbiased possibilities for comparisons.

The first case study analyses visitor spending and economic impact of nature-based tourists in the Simmental and Diemtigtal, two alpine valleys in the Berner Oberland, Switzerland, where 291 respondents in winter and 1009 in summer were asked about their spending, trip characteristics, motivations and activities. The survey area is quite representative for the Alps as it provides all relevant outdoor activities in winter, including several ski resorts of differing size and quality standards as well as purist nature tourism opportunities (Mayer et al., 2009). In addition to descriptive statistics and analyses of variance (ANOVAs), we built several multiple linear regression models (see Mayer and Vogt, 2016b for details).

Visitor spending was analysed according to the main activity respondents named (see Table 10.1). The results are differentiated into winter and summer season and day trippers and overnight visitors. In the summer season, ANOVA post-hoc tests reveal no significant differences in vacationers’ expenditures varying between CHF47.0 and 66.9. However, expenses of day trippers vary statistically significantly between downhill mountain bikers (MTB, CHF38.2) and hikers and walkers, who spend only half (CHF19.0 and 21.7, respectively). This is mainly because downhill bikers have to buy lift passes.

Table 10.1. Mean daily expenditure per person of visitors to Simmental and Diemtigtal in 2005/06 differentiated by main activities. (Own calculations, data based on Mayer et al., 2009.)

In the winter season no significant differences were found for vacationists (between CHF47.6 and 85.8) according to their activity, besides that the spending level generally was significantly higher than in summer (+36.8%). Indicatively, cross-country skiers had the highest daily expenditure per person for vacationers (CHF85.8), whereas alpine skiing/snowboarding took only the third rank (CHF72.6) following winter hikers (CHF85.7).

Among the day trippers, alpine skiers and snowboarders spent by far the most per person and day (CHF46.2). Explicit ecotourism activities, such as snowshoe walking (CHF11.0) or ski touring (CHF13.5) had the lowest spending for day trippers in winter and differ statistically significantly from the alpine skiers. Cross-country skiers and winter hikers spend only a third or a bit more than a third compared with the alpine skiers. However, we also need to treat these results with caution as the sample size of the activity groups is fairly small for some groups.

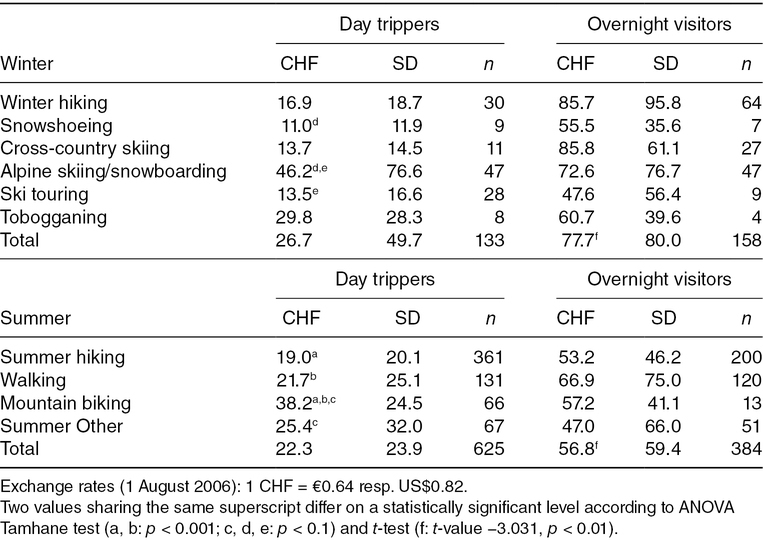

The results of the regression models are more generalizable because they control for the influences of the diverse survey points and make comparisons possible with all other variables treated as being equal. Table 10.2 shows the results of the overall model, which explains about half of the variance of mean daily expenditure in the winter and summer seasons. All winter and summer activity types, with MTB and tobogganing not being different at 0.05 level, spent considerably less than the reference category alpine skiing/snowboarding. The spending of hikers in summer (−75%) and winter (−60%) differed greatly. If one compares the beta values of summer and winter activities, it is obvious that winter activities tend to differ less from the reference category (−0.79 average beta vs. −1.09 for summer activities), which indicates higher expenditure in the winter.

Table 10.2. Multiple linear regression model of the spending behaviour of nature-based tourists in Simmental and Diemtigtal (all seasons, all visitors, all survey locations). (From Mayer and Vogt, 2016b, p. 107.)

Day trippers spent 58% less per person and day than overnight visitors. At Lenk, the most developed and most important location in the survey area (site type 1 s/w), the daily expenditure was highest. All other sites apart from Erlenbach (site type 2 s) show significantly less mean daily expenditure. At Chiley (−96%) and Meniggrund (−83%), both situated in Diemtigtal on popular ski touring trailheads (site type 4 w) where there is no infrastructure to spend any money, expenditure was especially low. At Grimmialp (−59%, site type 4 s/3 w) and Jaunpass (−69%, site type 3 s/w), which have both only small-scale ski areas in winter with even less infrastructure in summer, visitors also spent less.

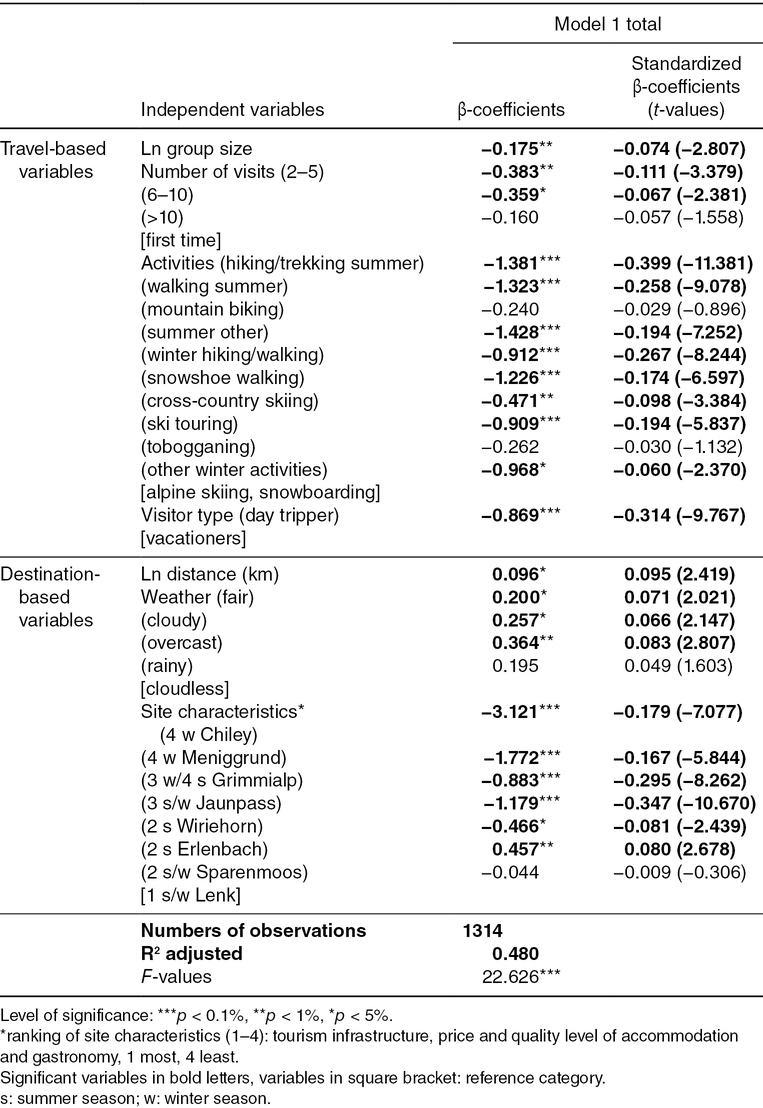

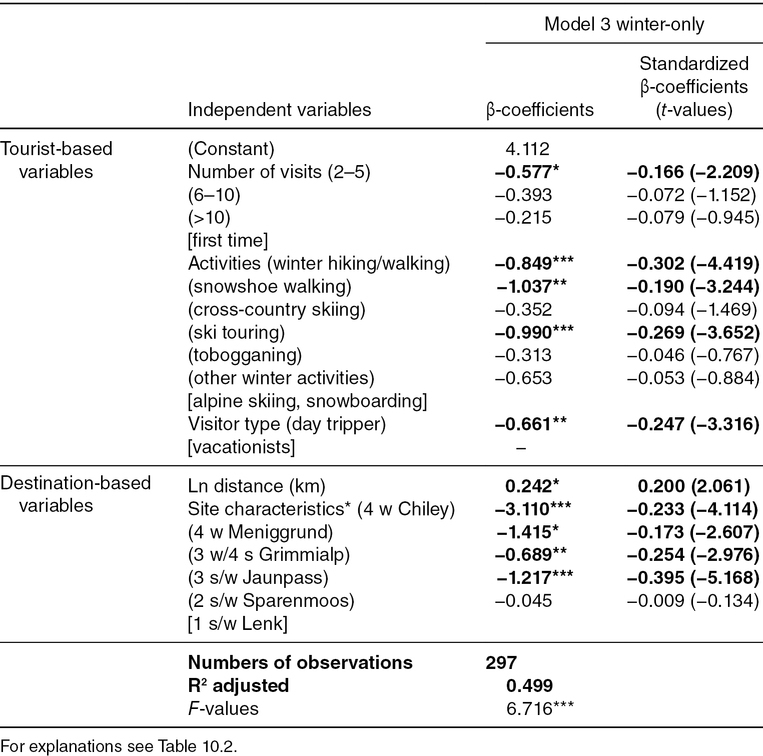

The winter-only model (see Table 10.3) produced quite similar results achieving a slightly better fit (approx. 50% of variance explained). All activities deviate negatively from the reference category alpine skiing, especially snowshoeing (−64.5%), ski touring (−62.8%) and winter hiking (−57.2%), with cross-country skiers and tobogganers showing the smallest deviations and no statistical significance (day trippers spend −48.4%). All survey sites (except Sparenmoos where the relatively high-spending tobogganers were sampled) differ negatively from Lenk with the largest ski area and the best tourism offer in terms of quality. Again, especially the ski touring and snowshoeing trailheads (Chiley, Meniggrund) are particularly negative (−95.5% and −75.7%).

Table 10.3. Multiple linear regression model of the spending behaviour of nature-based tourists in Simmental and Diemtigtal (winter, all visitors, all sampling locations). (Own calculations, data based on Mayer et al., 2009 and Mayer and Vogt, 2016b.)

Thus, our analyses show that expenditures related to winter sport activities in the two Swiss alpine valleys are often, but not in every case higher compared with those related to summer activities. Infrastructure-based activities like alpine skiing in winter or downhill MTB in summer lead to higher spending compared with more purist activities like ski touring. The latter are also often related to day trippers who spend significantly less compared with overnight visitors. However, the example of the vacationers also shows that high spending is not per se dependent on the main outdoor activity but on the chosen destination, its scope, quality and price level of the accommodation, gastronomy and retail offers. Nevertheless, there seems to be a correlation of these offer elements and characteristics with the state of development of tourism infrastructure like ski areas/cable cars. If one relates the expenditure data analysed here to the estimated annual frequentation of each activity group to derive the gross turnover and finally the economic impact, which was done by Mayer et al. (2009), it is obvious that the domination of the infrastructure-based winter activities is even stronger. Alpine skiing is a mass tourism activity related to mostly high daily expenditure (88% share of the regional economic impact in the winter season), while ski touring (0.13%) and snowshoeing (0.17%) are small niche activities with relatively low expenditures and a high share of day trippers. The second largest economic impact was generated by winter hiking/walking (9.2%); cross-country skiing accounted for 1.1%.

The Black Forest National Park designated in 2014 in south-western Germany provides an interesting case as it allows the direct comparison of the expenditure behaviour and economic relevance of alpine skiers in small-scale resorts, cross-country skiers and other less infrastructure-related nature tourism activities in the protected area. The Black Forest is an important winter sport destination for the surrounding areas of the Rhine valley and the agglomeration of Stuttgart. In the National Park region, 12 small-scale ski areas/lifts are situated. Cross-country skiing has a long tradition in the region. Thus, the National Park took over the management of 154 km of tracks (Job and Kraus, 2015).

The case study is based on 2020 interviews (year-round) with 507 visitors conducted during the winter season including 215 interviews with alpine skiers (in five ski areas) and 84 with cross-country skiers. The detailed surveys not only give insights into the spending but also into the trip characteristics, motivation and the role of the National Park for the trip decision. The methodology is based on the standard procedure for economic impact analysis in protected areas in Germany by Job et al. (2016). Parallel visitor counting and extrapolation allow the estimation of the economic impact of the different activity groups. The first entries of eight ski areas/lifts were derived from interviews with the operators; one was covered by own counting while the remaining three were estimated in relation to number of lifts, their lengths, capacity and opening time based on the revealed data of the other areas. Cross-country skier frequentation was conservatively extrapolated based on counting from two important trailheads (Job and Kraus, 2015).

Overall, the at-that-time newly established National Park recorded 1.041 million visitor days, among them 142,500 by alpine skiers (13.7%) and 50,000 by cross-country skiers (4.8%) in a very good season in terms of snow conditions (Job and Kraus, 2015). Black Forest National Park is dominated by day trippers (local day trippers 2 30.7%, non-local day trippers 29.5%), while overnight visitors account for only 39.8% of the visitor days (Mayer and Woltering, 2018). Alpine skiing in the Black Forest is even more strongly characterized by day trippers (81%), with only 19% overnight skiers. This distribution is even more extreme for the cross-country skiers with 91% to 9%. These one-sided distributions of the winter visitors are due to the nearby agglomerations of the Rhine valley. Winter recreationists’ demand reacts strongly to recent snowfalls and the weather conditions, which motivate them to visit the small ski areas close by, leading to congestion on weekends with good weather and snow conditions (Job and Kraus, 2015).

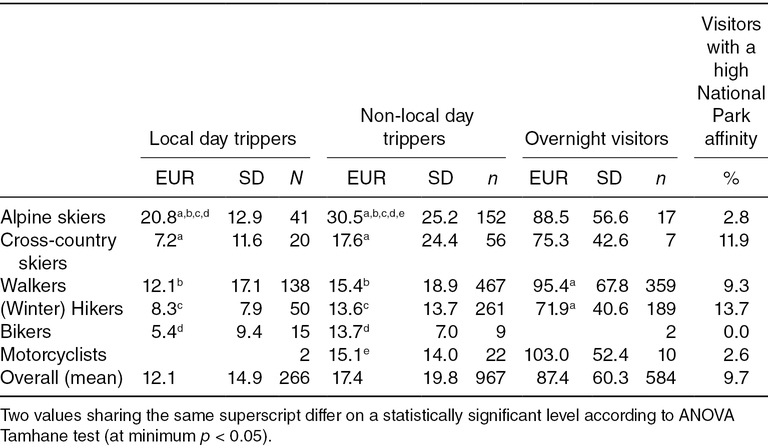

Table 10.4 provides an overview of the spending of the different activity groups in Black Forest National Park differentiated by the three main visitor types. Alpine and cross-country skiers as well as hikers show statistically significant differences in the mean daily expenditures per person for overnight guests, non-local day trippers and local day trippers, while for the walkers only local day trippers and overnight visitors and non-local day trippers and overnight visitors differ.

Table 10.4. Mean daily expenditure per person and National Park affinity of Black Forest National Park visitor activity groups in 2014/15. (Own calculations, data based on Job and Kraus, 2015.)

Among local and non-local day trippers the winter activities and especially alpine skiing lead to the highest per person and day spending (though cross-country skiing not for the local visitors). For both visitor types, alpine skiers differ statistically significantly from all other activity groups. This is not the case for overnight visitors where only walkers and hikers differ significantly. Alpine skiers rank only third.

Interestingly, activity groups also reveal inter-seasonal differences: the walkers staying overnight spend on average €122.9 in the winter season compared with only €89.2 (summer), €91.7 (autumn) and €95.5 (spring). These differences are statistically significant for the first three groups (p < 0.05, ANOVA tamhane post-hoc test). A converse effect holds true for day tripping walkers, who spend significantly less in winter (€11.0) compared with spring (€15.4) and autumn (€16.8, p < 0.05). For hikers, these effects could not be found. Thus, winter guests do not automatically spend more in any case compared with other seasons.

The National Park affinity varies significantly between the activity groups: alpine skiers (2.8%), motorcyclists (2.6%) and bikers (0%) do not care much about the protected area status of the region, which comes as no surprise given that the dependence on infrastructure of alpine skiers is not compatible with the National Park idea; walkers (9.3%) nearly reach the overall mean (9.7%); cross-country skiers (11.9%) and (winter) hikers (13.7%) surpass this threshold. This reflects the strong relatedness to nature of cross-country skiers.

Extrapolated to the overall number of visitor days, alpine skiers generate €5.692 million gross turnover in the park region (12.7%) leading to a regional income of €3.016 million, which translates to 109 income equivalents. Cross-country skiers reach €1.120 million (2.5%) and €0.561 million, respectively (20 income equivalents) (Job and Kraus, 2015). Thus, explicit winter sport activities account for 15.7% of the National Park’s regional economic impact. These results underline that winter tourism activities balance the tourism demand over the year, which contributes considerably to a better utilization of the tourism infrastructure.

Winter tourism is highly diverse and thus so also are visitor spending and their economic impact. There seems to be a tendency for higher spending in the winter season in mountain settings compared with the other seasons in addition to remarkably high expenditures in the home regions for equipment like skis (which we did not show in our two case studies). As expected, visitors pursuing infrastructure-related outdoor activities like alpine skiing spend the most. Important drivers for their higher spending are the high costs associated with lift passes, outdoor equipment and services like ski schools. In contrast, more purist and nature-related activities lead most often to lower expenditures and only relatively few respondents pursue them, which hints at a ‘sustainability-profitability-gap’ (Moeller et al., 2011). In addition to this rather low regional economic impact the ecological footprint of these activities due to the dominance of car access should not be neglected. The comparison between these extremes in terms of environmental impact, spending and visitor numbers also reminds us that we should not only take expenditure into consideration but also the frequentation, length of stay and multipliers. At the end of the day, it is the economic impact of outdoor activities that is the most relevant, but visitor spending is without doubt an important influencing factor.

However, our case studies show that alpine skiing does not necessarily lead to higher expenditures compared with other activities. This is because visitor spending depends on the region, its price level, tourism offer like the size of ski areas or retail quality but also on personal preferences, willingness to pay, etc. In this way, hybrid visitors might be another reason for diversity in expenditure, like for example ski tourers residing in costly luxury accommodation or alpine skiers staying in basic self-service huts. This underlines that visitor spending is not determined by the leisure activities alone (White and Stynes, 2008) but is influenced by a complex bundle of factors (see Table 10.2 and Table 10.3). As our first case study shows, multiple linear regression models are suitable to control for these various influencing factors. Therefore, specific onsite surveys taking local/regional characteristics into account are required. However, this leads to the methodological problem of very large sample sizes being necessary to enable coverage of niche activities with an adequate sub-sample size, which is an issue with both of our case studies (though the first one more than the other).

All in all, compared with the summer season, winter tourists in general spend more money, which underlines the high economic importance of winter tourism for many peripheral valleys in mountain regions. Thus, high investments in snowmaking and quality improvements of cable cars and ski lifts can still be justified by the argument of economic importance. However, it is because of this importance that threats to winter tourism by climate change and other influencing factors should be taken seriously, and diversification strategies for the winter season be fostered as well as the non-snow-dependent seasons strengthened.

1 BAK Basel (2012) compared the prices of circa 4700 three-star hotels (standard double rooms) in the Alps for 2011 in the winter and summer high seasons. In the Alps hotel prices in winter are 17% higher compared with the summer.

2 Defined as coming from all municipalities that share a part of the park area and/or directly bordering the protected area.

Amt der Tiroler Landesregierung (2017) Der Tourismus im Winter 2016/17. Available at: https://www.tirol.gv.at/fileadmin/themen/statistik-budget/statistik/downloads/FV_Winter_2017.pdf (accessed 14 July 2018).

BAK Basel (2012) Bedeutung, Entwicklungen und Herausforderungen im Schweizer Sommertourismus. Basel. Available at: https://www.seco.admin.ch/dam/seco/de/dokumente/Standortfoerderung/Tourismus/Archiv/Studie_Sommertourismus_2012.pdf.download.pdf/Schweizer%20Sommertourismus_2012.pdf (accessed 7 September 2018).

Bayerisches Staatsministerium für Wirtschaft, Infrastruktur, Verkehr und Technologie (StMWIVT) (2007) Seilbahnen in Bayern. StMWIVT, Munich, Germany.

Brida, J.G. and Scuderi, R. (2013) Determinants of tourist expenditure: a review of microeconometric models. Tourism Management Perspectives 6, 28–40. DOI:10.1016/j.tmp.2012.10.006

Bundesverwaltungsgericht Republik Österreich (2018) Decision ‘Schigebietserweiterung Hochsonnberg’. Geschäftszahl (GZ): W225 2014492-1/128E. Vienna, Austria.

CIPRA (2017) Sonnenwende im Wintertourismus. Positionspapier. Available at: https://www.cipra.org/de/positionen/wintertourismus/CIPRA%20Positionspapier_Sonnenwende%20im%20Wintertourismus.pdf/inline-download (accessed 27 September 2018).

Feichtner, D. (2017) Kompetenz, die sich bezahlt macht. Saison 05/17, 8–10.

Fredman, P. (2008) Determinants of visitor expenditures in mountain tourism. Tourism Economics 14(2), 297–311.

Job, H. and Kraus, F. (2015) Regionalökonomische Effekte des Tourismus im Nationalpark Schwarzwald. Unpublished report, Munich, Germany.

Job, H., Merlin, C., Metzler, D., Schamel, J. and Woltering, M. (2016) Regionalwirtschaftliche Effekte durch Naturtourismus in deutschen Nationalparken als Beitrag zum Integrativen Monitoring-Programm für Großschutzgebiete. Bundesamt für Naturschutz, Bonn-Bad Godesberg, Germany.

Jülg, F. (2007) Wintersporttourismus. In: Becker, C. et al. (eds) Geographie der Freizeit und des Tourismus. Bilanz und Ausblick, 3rd edn. Oldenbourg, Munich, Germany, pp. 249–258.

Kleissner, A. (2012). Die gesamtwirtschaftliche Bedeutung des Wintersports in Österreich. Forum Zukunft Winter. Kaprun, 5 November 2012. Available at: https://docplayer.org/37831878-Die-gesamtwirtschaftliche-bedeutung-des-wintersports-in-oesterreich-anna-kleissner-sportseconaustria.html (accessed 27 September 2018).

Leitner, W. (1984) Winterfremdenverkehr. Entwicklung, Erfahrungen, Kritik, Anregungen. Bundesland Salzburg 1955/56-1980/81. Amt der Salzburger Landesregierung, Salzburg, Austria.

MANOVA (2016) Wertschöpfung durch österreichische Seilbahnen. Wertschöpfung im Winter. Endbericht Oktober 2016, Wien, Austria. Available at: https://www.wko.at/branchen/transport-verkehr/seilbahnen/Wertschoepfung-durch-Oesterreichische-Seilbahnen.pdf (accessed 25 August 2018).

Mayer, M. and Vogt, L. (2016a) The economic effects of tourism and its influencing factors. An overview focusing on the spending determinants of visitors. Zeitschrift für Tourismuswissenschaft 8(2), 169–198. DOI:10.1515/tw-2016-0017

Mayer, M. and Vogt, L. (2016b) Bestimmungsfaktoren des Ausgabeverhaltens von Naturtouristen in den Alpen – das Fallbeispiel Simmental und Diemtigtal, Schweiz. In: Mayer, M. and Job, H. (eds) Naturtourismus – Chancen und Herausforderungen (=Studien zur Freizeit- und Tourismusforschung 12). MetaGIS, Mannheim, Germany, pp. 99–111.

Mayer, M. and Woltering, M. (2018) Assessing and valuing the recreational ecosystem services of Germany’s national parks using travel cost models. Ecosystem Services 31(Part C), 371–386. DOI:10.1016/j.ecoser.2017.12.009

Mayer, M., Kraus, F. and Job, H. (2011) Tourismus – Treiber des Wandels oder Bewahrer alpiner Kultur und Landschaft? Mitteilungen der Österreichischen Geographischen Gesellschaft 153, 31–74. DOI:10.1553/moegg153s31

Mayer, M., Wasem, K., Gehring, K., Pütz, M., Roschewitz, A. and Siegrist, D. (2009) Wirtschaftliche Bedeutung des naturnahen Tourismus im Simmental und Diemtigtal – Regionalökonomische Effekte und Erfolgsfaktoren. Eidg. Forschungsanstalt für Wald, Schnee und Landschaft WSL, Birmensdorf, Switzerland.

Mehmetoglu, M. (2007) Nature-based tourists: the relationship between their trip expenditures and activities. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 15(2), 200–215. DOI:10.2167/jost642.0

Moeller, T., Dolnicar, S. and Leisch, F. (2011) The sustainability–profitability trade-off in tourism: can it be overcome? Journal of Sustainable Tourism 19(2), 155–169. DOI:10.1080/09669582.2010.518762

Pouta, E., Neuvonen, M. and Sievänen, T. (2006) Determinants of nature trip expenditures in Southern Finland – implications for nature tourism development. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism 6(2), 118–135. DOI:10.1080/15022250600658937

Rütter, H., Müller, H., Guhl, D. and Stettler, J. (1995) Tourismus im Kanton Bern. Wertschöpfungsstudie. FIF, Bern/Rüschlikon, Switzerland.

Rütter, H., Berwert, A., Rütter-Fischbacher, U. and Landolt, M. (2001) Der Tourismus im Wallis. Wertschöpfungsstudie. Rüschlikon/Siders, Switzerland.

Rütter, H., Rütter-Fischbacher, U. and Berwert, A. (2004) Der Tourismus im Kanton Nidwalden und in Engelberg. Wertschöpfungsstudie. Rüschlikon, Switzerland.

Seilbahn.net (2016) Sölden-Pitztal: Erster Schritt in gemeinsame Zukunft. 18.07.2016. Available at: www.seilbahn.net/sn/index.php?i=60&kat=1&j=1&news=7238 (accessed 27 September 2018).

Siegrist, D. and Gessner, S. (2011) Klimawandel: Anpassungsstrategien im Alpentourismus. Ergebnisse einer alpenweiten Delphi-Befragung. Zeitschrift für Tourismuswissenschaft 3(2), 179–194. DOI:10.1515/tw-2011-0207

Soboll, A., Klier, T. and Heumann, S. (2012) The prospective impact of climate change on tourism and regional economic development: a simulation study for Bavaria. Tourism Economics 18(1), 139–157.

Statistik Austria (2016) Beherbergungsstatistik ab 1974 nach Saison. Available at: http://statcube.at/superwebguest/login.do?guest=guest&db=detouextsai (accessed 27 September 2018).

Steiger, R., Scott, D., Abegg, B., Pons, M. and Aall, C. (2019) A critical review of climate change risk for ski tourism. Current Issues in Tourism 22(11), 1343–1379. DOI:10.1080/13683500.2017.1410110

Verband Deutscher Seilbahnen und Schlepplifte e.V. (VDS) (2015) Wirtschaftliche Effekte durch Seilbahnen in Deutschland. VDS, Munich, Germany.

White, E.M. (2017) Spending patterns of outdoor recreation visitors to national forests. General Technical Report PNW-GTR-961. US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station, Portland, Oregon.

White, E.M. and Stynes, D.J. (2008) National Forest visitor spending averages and the influence of trip-type and recreation activity. Journal of Forestry 106(1), 17–24.

Wirtschaftskammer Österreich (WKO) (2018) Tourismus und Freizeitwirtschaft in Zahlen. Österreichische und internationale Tourismus- und Wirtschaftsdaten 54. Ausgabe, Juni 2018. Vienna, Austria. Available at: https://www.wko.at/branchen/tourismus-freizeitwirtschaft/tourismus-freizeitwirtschaft-in-zahlen-2018.pdf (accessed 25 August 2018).