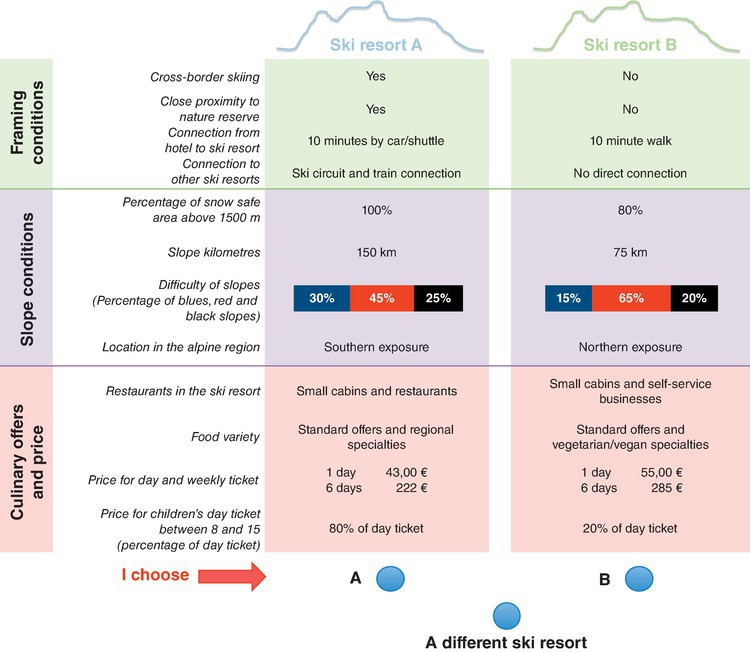

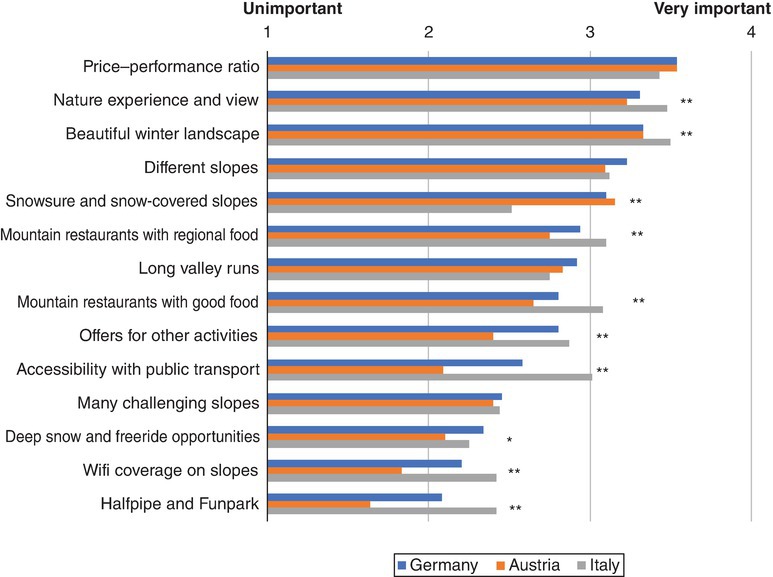

Fig. 17.1. Example of a discrete choice experiment depicting the three attribute blocks with a total of 12 attributes: framing conditions, slope conditions, culinary offer and price.

Institute of Landscape Development, Recreation and Conservation Planning, University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences, Vienna, Austria

*E-mail: ulrike.proebstl@boku.ac.at

Ski resorts in South Tyrol, the most northern part of Italy, are frontrunners in destination planning and management. Located at the geographical heart of the Alps and on their southern side, South Tyrol is an attractive destination for tourists from many countries in different target markets. However, to maintain this success it is necessary to continuously analyse new trends and to understand the motivations and behavioural intentions of guests – at least of those belonging to the main target groups. In addition, research findings show that today’s customers – especially in winter tourism – are less loyal than they used to be in the past (ÖHV, 2012). Hence, it will be vital to respond to new trends and emerging preferences, such as vegan cuisine, internet access on slopes and cosy mountain hut restaurants (as potential replacements for self-service cantinas). Therefore, the region of Sexten, in cooperation with the University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences, Vienna, and local stakeholders, decided to examine future trends in more detail in order to be better prepared for future tourists. In the first meetings, practitioners involved in the field stated that in their opinion ‘cultural differences’ are key to an understanding of current and future decision making and constituted a major driver accounting for differences in demand. We based a crucial hypothesis for the following research on this practical expertise and tried to verify and understand the concept of cultural differences in the context of winter tourism.

Although tourism research has for decades explored cultural effects, they are still perceived as a complex multidimensional phenomenon that is difficult to define (for an extended discussion of terminology, see Reisinger and Turner, 2003). In tourism research, ‘culture’ is commonly defined as the set of customs, values, norms, beliefs, habits, arts and lifestyle patterns shared within a group or society (Hall, 1976; Reisinger and Turner, 2003; Kang and Moscardo, 2006). In addition, Reisinger and Turner (2002) point out that culture refers to the stable and dominant character of a society shared by most of its individuals and remaining constant over long periods of time. The concept of ‘culture’ may also be regarded as a helpful guide to behavioural interpretation in various contexts (Kim and Gudykunst, 1988; Burdge, 1996). The term ‘cross-cultural’ describes relationships between different cultures (Gibbs, 2001). Cross-cultural differences are perceived as particularly important in tourism planning and management (Turner et al., 2002; Kang and Moscardo, 2006). The research on differences in values, rules of social behaviour, perception and social interaction has contributed to three main fields of interest: the cultural background of tourists and its relevance for the experiences they seek out (Reisinger and Turner, 2002; Ng et al., 2007), the clients’ cultural background as the basis for successful marketing strategies (Ooi, 2002; Funk and Bruun, 2006) and, finally, the need for cross-cultural understanding to improve tourism management and to deal with clients from diverse cultural backgrounds (see, for example, Weiermair, 2000; Turner et al., 2002; Moscardo, 2004; Ortega and Rodriguez, 2007). In the context of a South Tyrolian ski resort, we are mainly interested in the experiences the various target groups are looking for.

Studies on outdoor recreation and nature-based tourism in Europe (Bell et al., 2007, 2009; Pröbstl et al., 2010; Landauer et al., 2012, 2013) document the importance of studying cross-continental differences: the popularity of many outdoor recreation and sports activities differs across European regions as a result of deviations in the availability of physical resources as well as the different status they hold in various cultures. All these studies confirm that culture strongly influences participation and non-participation in certain sports and that culture should, therefore, be taken into account when researching behaviour in leisure activities, outdoor recreation and tourism. This view is also reflected in tourism and business research (Hofstede, 1980). Research conducted by Triandis (1972) and Hofstede (1980, 1997) has presented ample evidence of differences and similarities among cultures. Recent literature has covered cultural differences in winter tourism only in the context of climate change disregarding the issue of destination choice and experiences desired by tourists in their winter holidays (Gössling et al., 2012; Landauer et al., 2012, 2013). Reisinger and Turner (2003) as well as Landis and Brislin (1983) report the relevance of cultural differences to an understanding of interpersonal interactions and product development, especially in tourism, as these cultural differences may influence behaviour, motivation and destination choice. Our main research questions, therefore, focus on the following aspects:

• Do the main motives and expectations concerning winter holidays in South Tyrol differ among the main target regions (Germany, Austria and Italy)?

• Are these expectations likely to influence destination choice?

• Do cultural experiences – such as regional specialities, the atmosphere in the provided infrastructure and the southern alpine ambience – contribute to a ‘special’ holiday experience and increase a region’s attractiveness?

Sexten, located in the holiday region ‘Drei Zinnen’, is well known as a summer and winter tourism destination and hosts around 7% of all yearly overnight stays in South Tyrol (IDM Südtirol, 2018). In order to investigate future tourism trends based on cultural differences, a rather large study area was selected, which allowed us to consider travel flow effects as well as the overall attractiveness of the region compared with similarly situated destinations.

In order to deepen our understanding of and knowledge about how cultural differences shape skiing motivation, behaviour and destination choice, the study applied an online questionnaire that targeted German, Italian and Austrian skiers or snowboarders who had already visited the study area for skiing or snowboarding day trips or vacations over the past 5 years. The survey consisted of 22 open- and closed-ended questions (i.e. multiple choice, dichotomous, rating scale [Likert scale questions (Likert, 1977)], and ordinal scale questions). In addition, a stated preference tool (a discrete choice experiment) was applied, which measured preferences on the basis of intended behaviour. The survey opened with questions relating to winter sports activities, the type of trips undertaken and regional preferences, followed by questions concerning the perception of ski resorts and important factors for their selection, the choice experiment, and future aspects including climate change and destination development. The questionnaire concluded with socio-demographic questions.

In survey-based choice experiments, respondents are asked to indicate which option they prefer the most out of multiple alternatives (i.e. their preferred ski resort). By systematically varying the levels of attributes out of which the different alternatives are comprised, it becomes possible to determine their influence on the stated choices (Auspurg and Liebe, 2011). This approach enables a more direct testing of causal relations than ‘common’ methods such as Likert scale questions allow. Choice experiments have been applied in nature-based tourism research for a range of purposes (e.g. Arnberger and Haider, 2005; Hunt et al., 2005; Lindberg and Fredman, 2005; Sorice et al., 2005; Brau and Cao, 2006; Unbehaun et al., 2008, Pröbstl-Haider and Haider, 2014). Several publications have further demonstrated the suitability of discrete choice experiments for cross-cultural contexts (Rose et al., 2009; Landauer et al., 2012). The method has been deemed highly useful in forecasting likely behaviour changes in reaction to changed circumstances or the hypothetical availability of certain consumer goods (Louviere et al., 2000; Landauer et al., 2013). Both the complexity of tourist destinations and the fact that many offers do not currently exist (such as vegan cuisine options) suggest perfect conditions for the application of a discrete choice experiment.

Choice experiments rely on multivariate hypothetical scenarios (composed of several relevant attributes), which, in this case, described two skiing destinations. Respondents are repeatedly asked to choose one out of these two destinations. Assuming that these responses are consistent with random utility theory (RUT), they can be analysed with a multinomial logit model (MNL) (McFadden, 1974), or a related logistic choice model. RUT, formalized by Manski (1977), posits that any individual will try to maximize utility when making choices. For the analysis, the total utility is decomposed into a deterministic component (observable) and a random component (McFadden, 1974; Ben-Akiva and Lerman, 1985; Louviere et al., 2000). The probability of selecting one alternative over another can then be described as the exponent of all measurable elements of the selected alternative over the sum of the exponents of all measurable elements of the second alternative. On the basis of this correlation, a use-value for every attribute and its levels can be calculated, which subsequently allows for a depiction of the acceptance of every contingent alternative with the help of a decision support tool. This tool also allows for a depiction of choices of different target groups (i.e. Germans, Austrians, Italians), which are directly based on the participants’ preferences indicated in the choice experiment. The interface of the decision support tool mirrors the choice experiment. Each level of every attribute can be altered individually, thereby ‘creating’ different hypothetical ski resorts. The results can provide significant information for decision makers based on participants’ actual preferences.

The choice experiment applied in this survey was framed as follows: ‘Like any tourist destination, alpine ski regions must regularly take a critical look at the future development of their services. The wishes and needs of their guests constitute an important basis for this development. In the following, we ask you to evaluate the attractiveness of alpine ski resorts for your winter holidays. To do this, you will need to choose six times between two ski areas. Please select the more attractive ski resort “A” or “B”. If you do not like either of the two ski areas, choose “a different ski area”.’

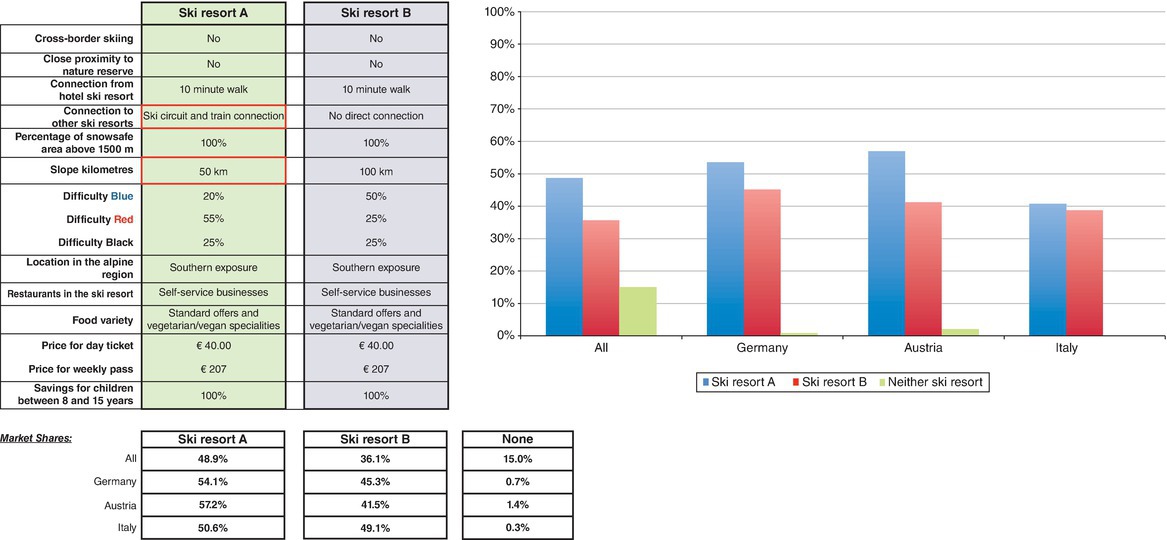

Figure 17.1 shows the choice experiment, which contains 12 attributes divided into three blocks. The first block describes the framing conditions such as the resorts’ cross-border skiing opportunities, proximity to protected areas, distance and type of connection from the hotel to the cable car, and connectivity to other resorts (by ski circuit or train). The attributes in the second block (‘slope characteristics’) describe the main characteristic of each resort including the percentage of snow secure areas above 1500 m, the total length of slopes, the distribution of slopes according to their difficulty levels and its location within the European Alps (north or south). The last block (‘catering and costs’) includes culinary offers in the resort, the range of dishes, the costs of ski passes and the discounts available for children between 8 and 15 years of age.

Fig. 17.1. Example of a discrete choice experiment depicting the three attribute blocks with a total of 12 attributes: framing conditions, slope conditions, culinary offer and price.

The hypothetical scenarios of the choice experiment were created and combined into choice sets through an orthogonal fractional factorial design produced in SAS using a ‘mktex’ macro (Deff 88.2824, Aeff 74.8455, Geff 94.423, APSE 0.9071). The design plan contained 96 choice sets. Out of those, a respondent evaluated six randomly chosen choice sets. The opt-out alternative was omitted to establish realistic scenarios and trade-offs.

Collected data were analysed in IBM SPSS Statistics 21. A Latent Gold choice model was executed with the choice experiment data in Latent Gold 5.0. In order to investigate cultural differences, the German, Austrian and Italian samples were analysed separately and were used to design a decision support tool.

The online questionnaire was made available between 1 and 25 July 2017. German, Austrian and Italian panels were purchased from renowned providers. The following sections give an overview of the results of the surveyed winter tourists and the particular responses of Austrian, German and Italian skiing and snowboarding vacationers.

Overall, 2400 participants (800 from each country) responded to the questionnaire: 75% were skiing or snowboarding vacationers, while 25% were classified as day visitors or season ticket holders. The respondents were between 17 and 75 years old (42.44 average age) and displayed an equal gender distribution (48% female, 52% male). The sample featured a high education level but represented all income classes. The three main activities of winter vacations were skiing (66%), winter hiking (11%) and cross-country skiing (8%). The self-evaluation of respondents revealed that about a third classified themselves as advanced skiers/snowboarders. However, the sample also included all kind of experiences: less experienced skiers/snowboarders (beginners 19%, those returning to the sport 26%, advanced 33%, experienced 20%, professional 2%).

From here on out, the presented results refer only to skiing or snowboarding vacationers from the three target countries.

The first evident differences emerge from the samples’ responses on the activities they planned for their winter vacations. While Austrian participants mainly planned to ski (70%), tourists from Italy and Germany – to a significantly higher percentage – also enjoyed winter hiking and cross-country skiing. Simultaneously, the Austrian sample evaluated itself as more experienced (30% experienced and 3% experts) than German (16% and 1%) and Italian (7% and 0.3%) visitors. About one-third of Italian participants saw themselves as beginners, which corresponds with a low percentage of Italians choosing to ski during their vacations. The results also revealed differences concerning the social aspect of skiing/snowboarding among the different samples. While 46% of German visitors skied with their partner, Austrian and Italian vacationers displayed different social patterns. Among Italian guests, skiing with the whole family seems to be much more common (30%) than among the other two nationalities. This also applies to skiing with friends. The results show that in Italy vacations are considered much more of a ‘social event’ than in the other two countries. Italian participants were, moreover, the most active in terms of short-term and recreational stays. Just over one-third of all day visitors made regular 1–2-day skiing trips.

The self-owned car constituted the primary means of transport among participants of all three countries. While the particular combination of car and public transport used to reach a holiday destination could potentially offer valuable insights, public transport by itself played a subordinate role, in particular among Austrian participants. Italians used their own cars significantly less often and were more willing to switch to other modes of transport, while Austrian and German participants predominantly drove to their skiing/snowboarding destinations. Over the past decade, South Tyrol has made an effort to improve local train connections in order to pursue two goals: (i) to expand opportunities for the public to reach resorts, and (ii) to connect settlements to ski resorts, thereby offering a new ski circuit of local trains directly connected to cable car stations. While German and Italian guests appeared to be somewhat attracted by this offer, Austrian guests were significantly less interested in train services.

Finally, respondents were asked about their perception of climate change. Awareness of the issue was high among all three nationalities, as the majority believed that first signs of a change in climate are already visible. However, the number of Italian guests stating their uncertainty or arguing that the effects of climate change will occur at a later stage was discernibly higher compared with the other two samples.

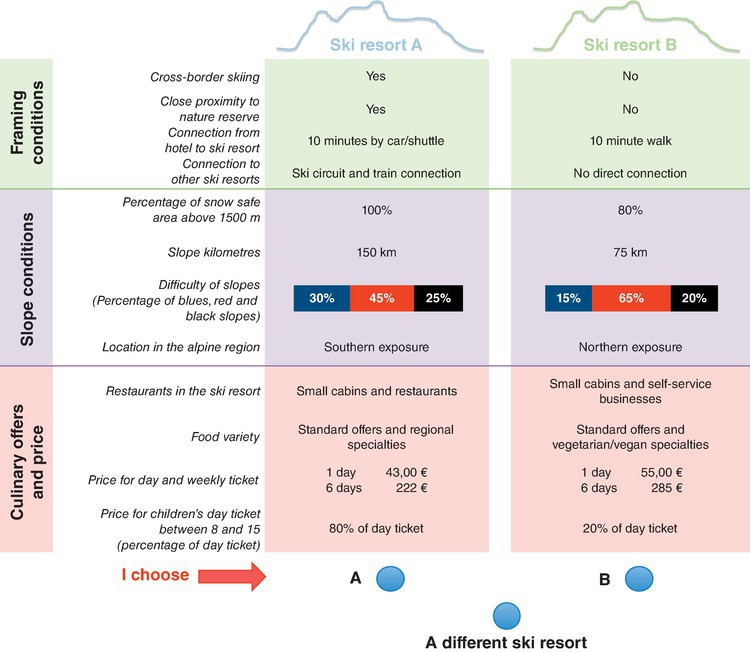

Respondents were asked to rate different aspects of winter sports activities on a scale from 1 (unimportant) to 4 (very important). Overall, the most important aspects all participants cited were ‘being outdoors and being active in fresh air’, ‘enjoying nature’, and ‘experiencing the winter landscape’. A closer look at the three different nationalities reveals a number of significant differences.

As mentioned in the introduction, it is likely that cultural differences will be expressed in different motivations and expectations. The following figure (see Fig. 17.2) shows that Italian respondents in particular rated social experiences as very important (e.g. ‘having fun with others’, ‘spending time with family and friends’, ‘making new acquaintances’, and ‘getting to know the region, country and people’). Social and regional aspects were significantly more important for Italian tourists and day visitors than for Austrian and German participants.

Fig. 17.2. Motivation for and important aspects of winter sports activities; ** indicates significance at a 5% level among the three countries.

For German guests, the pursuit of outdoor activities surrounded by nature was much more important (e.g. ‘being active in fresh air’, ‘experiencing high mountain regions’, ‘witnessing striking landscape elements’). Furthermore, ‘enjoying the sunshine’ was much more important to them than to Italian guests.

As for Austrian respondents, the chance to practise their chosen outdoor sport and to improve their technique were considered the most important aspects.

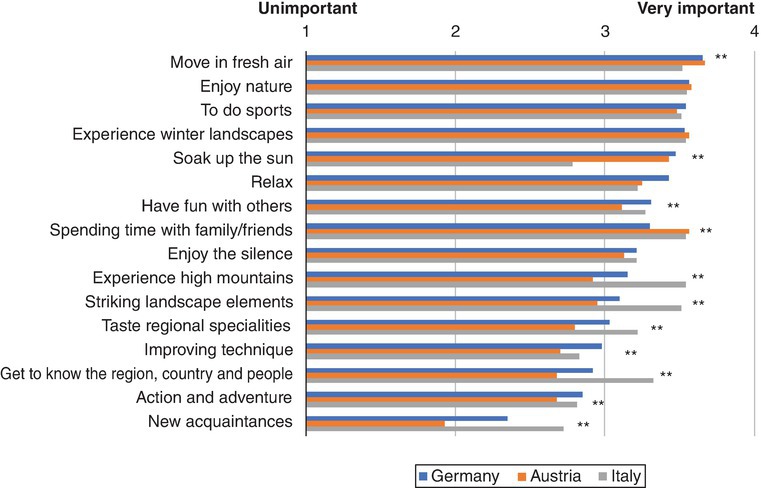

When it comes to selection criteria for the choice of a ski resort, the range of influencing factors was similar among all participants, yet they differed in the way they prioritized different aspects. For German and Austrian skiers/snowboarders, the price–performance ratio was the most important criterion, while Italian participants considered the beauty of the winter landscape to be the most crucial factor. In accordance with the main findings concerning motivational factors (see Fig. 17.2), all respondents highlighted the relevance of the ‘nature experience and view’, the ‘beautiful winter landscape’ and the availability of ‘different slopes’. The least important features when selecting a ski resort were a WiFi connection on slopes and technical infrastructure such as halfpipes (see Fig. 17.3).

Fig. 17.3. Important criteria when selecting a ski resort for a vacation; ** indicates significance at a 5% level; * indicates significance at the 10% level among the three countries.

With minor exceptions, we again observed significant differences among the three nationalities confirming previous findings. For the Austrian sample, the quality of slopes and the level of snow security was of utmost interest, which differs significantly from the other samples. Public transportation, on the other hand, was perceived as unimportant by this sample, which complies with the findings presented in Fig. 17.2. Italian tourists further reiterated their interest in ‘nature experience’, the ‘winter landscape’, ‘regional food’, ‘good mountain restaurants’ and ‘accessibility via public transport’. Aside from a common interest in ‘nature experience’, it seems that German vacationers most appreciated diversity and a high variety of recreational offers (‘different slopes’, ‘long ski runs’, ‘many challenging slopes’ and ‘free ride opportunities’).

Cultural experiences and proximity to a nature reserve emerged as particularly important in the overall analysis. In addition, all respondents preferred smaller ski huts and restaurants compared with large-scale self-service cantinas. In general, regional specialities were preferred over vegetarian or vegan offers. The distance from the hotel to the ski resort was preferred to be short and mode of travel should be comfortable; walking distance was deemed ideal. The attractiveness of a resort increased with size – but not indefinitely (up to 80 km). The choice experiment again underlined the crucial importance of the price level: most vacationers were price-sensitive as evidenced by the way a resort’s appeal decreased with an increase in pricing. However, a discounted skiing pass for children was only considered relevant by Italian respondents.

The following examples describe the effects of potential management strategies pursued by the cable car enterprise in Sexten. They clearly demonstrate the trade-offs tourists are willing to make as well as their preferences among the proposed strategies.

As Sexten has in the past invested extensively in the improvement of its local train infrastructure, the question arises as to whether additional investments in train services are economically expedient. Linking the platforms of train stations directly to cable car stations, as well as connecting skiing resorts with each other via train will significantly improve accessibility and expand the entire ski circuit for both guests and locals. However, it was unclear whether customers recognized this benefit.

The decision support tool revealed that respondents were well aware of this new strategy. Figure 17.4 shows two ski resorts (A and B) that differ only in size and the train connection they offer to other ski resorts (highlighted in red). Results indicate that the majority in all countries preferred the smaller ski resort ‘A’, which features a train connection, in spite of the fact that larger resorts are generally preferred. Even vacationers from Austria and Germany, who include more experienced skiers usually aiming for larger resorts, were highly attracted by this offer, despite resort ‘A’ being only half the size of resort ‘B’. This trade-off – ‘connectivity in return for size’ – supports the strategy pursued by the South Tyrolean cooperation of ski resorts, which Sexten is a part of.

Fig. 17.4. The decision support tool shows the relevance of size and train connection to other ski resorts by country. Differences between the ski resorts ‘A’ and ‘B’ are highlighted in red.

Sexten’s proximity to the Austrian border and other Italian regions affords unique opportunities: cross-border skiing and the experience of different lifestyles, regional specialities and landscapes. As a unique feature, this effect has not been investigated before; hence, the question arises if this kind of offer would be of particular interest to vacationers. In addition, testing the economic advantages of a southern alpine exposure as well as of culinary offers provided in attractive smaller establishments such as mountain cabins and restaurants could be of central interest to management in the tourist sector. To this end, a southern resort featuring cross-border skiing opportunities, small restaurants and regional delicacies was contrasted in the decision support tool with a ski resort in the northern part of the Alps with larger infrastructure, no regional food offers, but a significantly lower price for day tickets (see Fig. 17.5). The result revealed that Austrian and German respondents preferred the cross-border experience in the southern part of the Alps despite the higher total costs, which are ordinarily rejected. Italian tourists, on the other hand, were attracted by the resort in the northern part of the Alps, which could be attributed to a desire to experience something new and different rather than the southern parts of the Alps and their familiar lifestyle. However, all things considered, location and a lower price level were not able to fully compensate for other aspects such as culinary experiences.

Fig. 17.5. Effects of cross-border skiing, location in the Alps, culinary offers and size of restaurants combined with a higher price level.

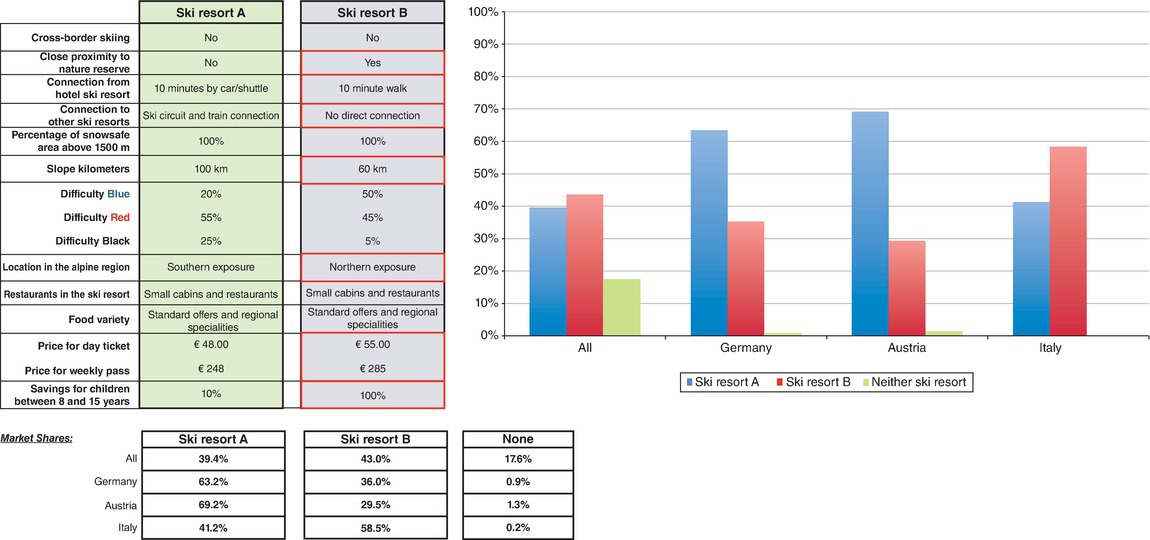

In light of the discussion on the relevance of cultural differences, the question arose whether it is possible to generate a hypothetical ski resort that is highly appreciated by one nationality but dismissed by the others. In order to test this aspect, one choice set was designed to reflect the values, motivations and preferences of the Italian sample. The aim was to determine whether this resort would be preferred by Italian respondents but disliked by German and Austrian tourists. Figure 17.6 depicts a relevant example. Ski resort ‘B’ was characterized by attractive natural conditions, convenient connections from the hotel to the ski resort, a comparatively smaller size without connections to other resorts, slopes of a low difficulty level (50% blue and only 5% black) and a 100% discount for children. Despite resort ‘B’ being more expensive than the alternative resort ‘A’, all needs and demands of the Italian target group were clearly met, as they significantly preferred resort ‘B’. Figure 17.6 also projects typical preferences cited by Austrian and German tourists, who clearly focus on the skiing aspect when selecting their favoured resorts. The latter preferred the more reasonably priced resort ‘A’ featuring more challenging slopes as well as more kilometres of slopes and a link to other resorts (via ski circuit and train).

Fig. 17.6. A tailor-made offer covering main interests can achieve higher price levels. Ski resort ‘B’ focuses on the demands of the Italian target group.

Our first research question asked whether the main motives and expectations for winter holidays in South Tyrol differed between the main target nationalities (Germany, Austria and Italy). The presented results clearly show significant differences between Italian and Austrian, as well as Austrian and German tourists with regard to their main motivations, values, needs and, especially, in their destination choices. The social aspect of skiing was of greater importance to the Italian sample, as the findings shown in Figs 17.2 and 17.3 illustrate, which is most likely a result of different cultural values. Being with family and friends, skiing in family units and enjoying their time together were of significantly higher value to Italian vacationers, which was also reflected in the company they usually go skiing with. These differences were clearly evident in the respondents’ selection of resorts in the choice experiment. For their ‘socially focused’ skiing holidays, Italians did not require long and intricate slopes or connections to other resorts. Italian respondents instead sought readily accessible and easy slopes, which they could ski with family members with different levels of experience, and appreciated pricing systems that offered discounted day tickets for their children. These findings confirm our second research question demonstrating that different values, motivations and expectations are likely to influence destination choice. The results can be interpreted as evidence of cultural inclinations, which is further corroborated by the outcome of the motivation and resort selection analyses. The importance of additional offers and services, such as WiFi on slopes, halfpipes and other sporting activities, highlights another set of differences based around cultural beliefs and values. By comparison, the Austrian sample expressed demands centred around different prerequisites from the others. While being with friends and family constituted an important motivation, the choice experiment clearly demonstrated the crucial significance of technical aspects within this target group. Austrians are skilled skiers, who want to improve their abilities and seek out different demanding experiences to test their boundaries. Hence, Austrian participants evidently selected resorts according to their particular values and motivations. Finally, German participants displayed both tendencies yet seemed to veer towards Austrian preferences. However, Germans celebrate their winter vacation and are less driven by technical motivations. Landscape (e.g. proximity to protected areas) and typical ‘regional’ experiences (e.g. regional cuisine) motivated this sample.

The conclusion that these differences are the result of diverging cultural values and motivations is not only in line with findings by other authors in this research field (e.g. Landis and Brislin, 1983; Reisinger and Turner, 2003), but is also supported by local stakeholders in Sexten, who were able to identify this relationship in the pre-study. With that in mind, we want to further emphasize the urgent need to improve the capacities of those working in the tourism sector to understand cultural differences and to translate this understanding into effective target group communication, tailor-made marketing campaigns, appropriate management and strategic development (Reisinger and Turner 2002; Turner et al. 2002).

In this context, the experience of cultural differences, such as regional specialities, atmosphere in the provided infrastructure and the southern or northern alpine ambience, have also been shown to increase a resort’s appeal. For German and Austrian tourists, the region around Sexten provides a desired southern alpine ambience, while in a similar manner northern alpine destinations with their distinctive atmosphere prove more attractive to Italians. Resort managers need to carefully address the specific preferences of their desired target group and adjust the respective marketing strategies accordingly, including the introduction of special offers.

Using a discrete choice experiment to investigate cultural differences is a fairly unique approach. Consistent with Landauer et al. (2012), this study demonstrated that the choice experiment and the subsequent decision support tool are excellent means to analyse data and communicate the complex findings to local stakeholders.

Interpreted with a view to differences in values and motivations, the highly divergent preferences that emerged in the choice experiment underline the importance of cultural differences for tourist holiday experiences, customer satisfaction and, ultimately, continued bookings.

In contrast to other methodologies such as the theory of planned behaviour, this modelling approach focuses on intended behaviour, which has become possible with the advent of more sophisticated multivariate statistical techniques (e.g. the multinomial logit model). Surveys based on a choice experiment also avoid the risk of a strategic response and, thereby, increase the reliability of responses (van Beukering et al., 2007). In addition, choice experiments allow for a consideration of hypothetical attributes such as tourism offers and, more importantly, ‘non-use values’ (Adamowicz et al., 1998a, b; van Beukering et al., 2007; Pröbstl-Haider and Haider, 2013; Pröbstl-Haider et al., 2015). The presented results once more underline the suitability of this approach for complex and challenging research questions.

The design of a choice experiment typically involves trade-offs between completeness and complexity. The presented choice experiment strives to be as inclusive as possible and, therefore, includes a large number of attributes (12 attributes with two to eight levels each). This is perceived as a cognitively demanding task for respondents. Although there is no golden rule as to the maximum number of attributes and levels that can be included in a choice experiment, the relevant literature generally tends to suggest between four and eight attributes (Curry, 1997; Ryan and Gerard, 2003), while keeping the number of levels to a minimum. According to these authors, scaling up complexity may lead to potential structural biases such as an increased preference for a ‘status quo alternative’ (see Boxall et al., 2009) or to an increased likelihood of non- or irrational responses (Louviere et al., 2000). However, there is little consensus and even less empirical data available regarding the optimum level of complexity. In addition, multiple studies have shown that choice experiments exceeding the eight-attribute threshold still produce reliable and meaningful results (e.g. Zweifel and Haegeli, 2014; Pröbstl-Haider et al., 2015; Rupf, 2015; Mostegl et al., 2019). Nevertheless, the high number of alternatives included in the choice experiment used in this study certainly increased the complexity of the choice task. Yet, none of the effects mentioned above could be observed. Three reasons may have helped avoid potential biases:

1. Market realism: Louviere et al. (2000) use the phrase ‘market realism’ to describe the degree to which a choice experiment matches the actual environment framing respondents’ real life decision making processes. The authors argue that the more closely the experiment resembles the actual market, the higher the content validity. The pursuit of a high degree of market realism obviously has an additional positive effect on the acceptability of more complex choice tasks. As the choice experiment in this study has been thoroughly discussed and refined with the help of practitioners and local stakeholders, it achieves a very high degree of market realism.

2. Presentation and design: The choice sets were diligently designed and pre-tested. The grouping of attributes, as well as the colour coding, were helpful in introducing a clear structure to the choice set. Furthermore, the design reduced the cognitive challenge for respondents.

3. Panel involvement: All respondents were recruited through country-specific panels. These respondents are highly motivated to participate in surveys and have most likely been exposed to complex survey questions in the past.

All things considered, the overall findings significantly benefited from the use of a complex choice experiment, as it is very likely that all crucial aspects were taken into account. The inclusion of additional attributes allowed for a better understanding of the trade-offs respondents are willing to make when choosing a ski resort. This advantage is further illustrated by the following two examples comparing findings from the choice model and conclusions drawn by other studies:

• The size of ski resorts – recently highlighted as the most important criterion for destination choice (Grabler, 2008, 2017) – is less relevant than expected. For resorts, size only constitutes a vital competitive advantage up to 80 km of slope length. If the size exceeds this threshold, the advantage is outweighed by other attributes. This finding indicates that size is interlinked with other factors and also depends on additional attributes, such as connectivity, technical skills of the target group (see, for example, the Italian sample) and the resort’s accessibility. Similar findings have been reported by Pröbstl-Haider et al. (2017) and Steiger et al. (2017).

• Another example can be found in the importance of day ticket prices. The literature is divided on this issue. While some studies and the media (e.g. Die Presse, 2013; Oe24 GmbH, 2017) highlight the relevance of price levels, others argue that they are irrelevant (Grabler, 2017). Based on the choice experiment, our study found that the overall price level of ski passes, as well as the perceived price–performance ratio play an important role; however, the results also show that the price level can be counterbalanced by other attributes. The decision support tool clearly indicates that suitable culinary offers, cross-border skiing and other cultural experiences can in fact compensate for a higher price. Nevertheless, caution must be exercised, as trade-off effects were shown to impact the national samples differently.

The study reveals that awareness of climate change is equally high in all three countries. However, the willingness to adapt seems to differ according to nationality. Other studies point out that climate change adaptation in the tourism sector needs to take different national cultures into account (Gössling et al., 2012; Landauer et al., 2013). Acknowledging a diverse range of challenges, approaches and capabilities in the debate on climate change adaptation runs counter to widely spread assumptions of homogenous tourist behaviour and preferences dominating research and policy or management recommendations. This assumption implies that any perceptual or behavioural insight gained in one place is – either directly or at least under similar socio-economic and socio-cultural conditions – transferable to another (e.g. Simpson et al., 2008). The findings of this study caution against such unquestioned transfers of climate change adaptation strategies – even within Europe. The results are also in line with research published by Bell et al. (2009), Pröbstl et al. (2010) and Landauer et al. (2013), who detect strong cultural differences across Europe in outdoor recreation and nature-based tourism.

In the case of Sexten, cultural differences related to climate change can, moreover, be identified in the use of public transport. Culturally different attitudes towards self-owned cars and car use in general are clearly reflected in respondents’ take on the use of public transport for skiing vacations. From a management perspective, significant investments in regional train connections and current negotiations to link local train services to the pan-European railway network may indeed prove effective in attracting new guests. However, these new customers will most likely be Italian, as this sample group stated they use public transport more often. Austrians and Germans, who clearly indicated their limited interest in public transport, will not be especially attracted by the offer. These findings strongly underline the difficulties efforts to convince Austrian and German skiers to switch to other, more sustainable means of transportation face. Yet, a better understanding of factors influencing destination choice may aid the development of new and customized products (e.g. travel packages), which may be able to increase the appeal of ‘alternative’ access to winter sports destinations in the Alps. While currently long-distance travellers are not likely to make significant use of train services, train networks have, nonetheless, already greatly contributed to climate change adaptation in the region. Train services have been positively received by locals and day trippers and a trickle-down effect has become evident. Trains reduce local traffic, create additional infrastructure for the local population to use and can generate added value by enabling a more sophisticated winter tourism product (e.g. integration in a ski circuit).

Given the ageing societies in all three countries, it may become necessary to promote winter holidays rather than skiing holidays, which allow vacationers to experience winter landscapes through a variety of activities (potentially involving less snow). The presented data, in this respect, demonstrate that other winter activities, such as winter hiking and cross-country skiing, are already highly relevant and will become even more so in the future due to decreasing snow reliability. Similar findings have been reported by Roth et al. (2018) for Germany.

Finally, even in the face of climate change and its effects on winter tourism, the alpine region has a clear advantage. The results of the study show that interest in visiting the region in summer is increasing. This opportunity should be made use of and further enhanced by forward-looking cross-marketing activities.

This research cooperation between Sexten, a skiing destination in South Tyrol, and the University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences in Vienna aimed to understand and address cultural differences in the demands of German, Austrian and Italian skiers and snowboarders in the region. The project was, moreover, designed to test new development and marketing opportunities. The results show that German, Austrian and Italian respondents differ significantly in their overall skiing motivations, values, the prerequisites they impose, as well as their specific destination choices. These differences were found to be even more relevant for segmentation than any other sampling criterion or combination of criteria (e.g. based on a Latent Gold segmentation). The performed analysis concluded that these differences can be reliably described as cultural differences, which were, furthermore, found to be crucial for marketing and product development. Since development options are limited, management strategies should put an emphasis on communicating specific touristic experiences. Hereby, cross-border experiences and local culinary delicacies offered in small restaurants can come into play, as they are especially in line with German and Austrian preferences, which welcome a special ‘southern alpine atmosphere’. Finally, the study highlighted that climate change adaptation will also need to take cultural differences into account.

Adamowicz, W., Boxall, P., Williams, M. and Louviere, J. (1998a) Stated preference approaches for measuring passive use values: choice experiments and contingent valuation. American Journal of Agricultural Economics. 80(1), 64–75.

Adamowicz, W., Louviere, J. and Swait, J. (1998b) Introduction to attribute-based stated choice methods. Final report to NOAA, US Department of Commerce. Advanis, Edmonton, Canada.

Arnberger, A. and Haider, W. (2005) Social effects on crowding preferences of urban forest visitors. Urban Forestry and Urban Greening 3(3–4), 125–136.

Auspurg, K. and Liebe, U. (2011) Choice-Experimente und die Messung von Handlungsentscheidungen in der Soziologie. Kölner Zeitschrift für Soziologie und Sozialpsychologie 6(2), 301–314.

Bell, S., Tyrväinen, L., Sievänen, T., Pröbstl, U. and Simpson, M. (2007) outdoor recreation and nature tourism: a European perspective. Living Reviews in Landscape Research 1 (2007-2), 1–46.

Bell, S., Simpson, M., Tyrväinen, L., Sievänen, T. and Pröbstl, U. (2009) European Forest Recreation and Tourism – a Handbook. Taylor & Francis, London.

Ben-Akiva, M. and Lerman, S. (1985) Discrete Choice Analysis. Theory and Application to Travel Demand. MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Boxall, P., Adamowicz, W.L. and Moon, A. (2009) Complexity in choice experiments: choice of the status quo alternative and implications for welfare measurement. The Australian Journal of Agricultural and Resource Economics 53(4), 503–519.

Brau, R. and Cao, D. (2006) Uncovering the macrostructure of tourists’ preferences. A choice experiment analysis of tourism demand to Sardinia. FEEM Working Paper 33/2006.

Burdge, R. (1996) Introduction: cultural diversity in natural resource use – case studies in cultural definitions of resource sustainability. Society and Natural Resources 9(4), 337–338.

Curry, J. (1997) After the basics: keeping key issues in mind makes conjoint analysis easier to apply. Marketing Research 9(1), 6–11.

Die Presse (2013) Austrians can’t afford to ski any more. Available at: https://diepresse.com/home/meingeld/verbraucher/1471119/Oesterreicher-koennen-sich-Skifahren-nicht-mehr-leisten (accessed 15 July 2018).

Funk, D. and Bruun, J. (2006) The role of socio-psychological and culture-education motives in marketing international sport tourism: a cross-cultural perspective. Tourism Management 28(3), 806–819.

Gibbs, M. (2001) Toward a strategy for undertaking cross-cultural collaborative research. Society and Natural Resources 14(8), 673–687.

Gössling, S., Scott, D., Hall, C.M., Ceron, J.-P. and Dubois, G. (2012) Consumer behavior and demand response of tourists to climate change. Annals of Tourism Research 39(1), 36–58.

Grabler, K. (2008) Kundenzufriedenheit als Schlüssel für den langfristigen Unternehmenserfolg. Mountain Manager 6, 44–45.

Grabler, K. (2017) Wahrnehmung, Bedeutung und Stellenwert ökologischer Aspekte für den Kunden. Available at: http://bergumwelt.boku.ac.at/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/Bergumwelt_2017_Grabler.pdf (accessed 15 July 2018).

Hall, E. T. (1976) Beyond Culture. Doubleday Anchor Press, New York.

Hofstede, G. (1980) Culture’s Consequences: International Differences in Work-Related Values. Sage, Beverly Hills, California.

Hofstede, G. (1997) Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind. McGraw-Hill, New York.

Hunt, L., Haider, W. and Bottan, B. (2005) Accounting for varying setting preferences among moose hunters. Leisure Sciences 27(4), 297–314.

IDM Südtirol – Alto Adige (2018) Touristische Zahlen und Fakten : Die Destination Südtirol im Jahr 2017. Available at: https://issuu.com/idm_suedtirol_altoadige/docs/broschu__re-de_rz_issue (accessed 10 January 2019).

Kang, M. and Moscardo, G. (2006) Exploring cross-cultural differences in attitudes towards responsible tourist behaviour: a comparison of Korean, British and Australian Tourists. Asia Pacific Journal of Travel Research 11(40), 303–320.

Kim, Y. and Gudykunst, W. (1988) Theories in Intercultural Communication. Sage, London.

Landauer, M., Haider, W. and Pröbstl-Haider, U. (2013) The influence of culture on climate change adaptation strategies. Journal of Travel Research 53(1), 96–110.

Landauer, M., Pröbstl, U. and Haider, W. (2012) Managing cross-country skiing destinations under the conditions of climate change – scenarios for destinations in Austria and Finland. Tourism Management 33(4), 741–751.

Landis, D. and Brislin, R.W. (1983) Handbook of Intercultural Training: Issues in Theory and Design. Pergamon Press, New York.

Likert, R. (1977) A technique for the measurement of attitudes. In: Summer, G.F. (ed.) Attitude measurement. Kershaw, London, pp. 149–158.

Lindberg, K. and Fredman, P. (2005) Using choice experiments to evaluate destination attributes: the case of snowmobilers and cross-country skiers. Tourism 53(2), 127–140.

Louviere, J., Hensher, D.A. and Swait, J. (2000) Stated Choice Methods. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK.

Manski, C. (1977) The Structure of random utility models. Theory and Decision 8(3), 229–254.

McFadden, D. (1974) Conditional logit analysis of qualitative choice behaviour. In: Zahembka, P. (ed.) Frontiers in Econometrics. New York Academic Press, New York, pp.105–142.

Moscardo, G. (2004) East versus west: a useful distinction or misleading myth? Tourism 52(1), 7–20.

Mostegl, N.M., Pröbstl-Haider, U., Jandl, R. and Haider, W. (2019) Targeting climate change adaptation strategies to small-scale private forest owners. Forest Policy and Economics 99, 83–99 . DOI:10.1016/j.forpol.2017.10.001

Ng, S.I., Lee, J.A. and Soutar, G.N. (2007) Tourists’ intention to visit a country: the impact of cultural distance. Tourism Management 28(6), 1497–1506.

Oe24 GmbH (2017) Price shock, skiing will be more expensive this year. Available at: www.oe24.at/businesslive/oesterreich/Preis-Schock-Skifahren-wird-heuer-noch-teurer/303704875 (accessed 15 July 2018).

ÖHV – Österreichische Hoteliervereinigung (2012) Österreichs Destinationen im Vergleich: Entwicklung 2005 bis 2010. Destinationsstudie und -karte der Österreichischen Hoteliervereinigung. ÖHV, Vienna, Austria.

Ooi, C.-S. (2002). Contrasting strategies. Tourism in Denmark and Singapore. Annals of Tourism Research 29(3), 689–706.

Ortega, E. and Rodríguez, B. (2007) Information at tourism destinations. Importance and cross-cultural differences between international and domestic tourists. Journal of Business Research 60(2), 146–152.

Pröbstl, U., Wirth, V., Elands, B.H.M. and Bell, S. (2010) Management of Recreation and Nature-Based Tourism in European Forests. Springer, Berlin.

Pröbstl-Haider, U. and Haider, W. (2013) Tools for measuring the intention for adapting to climate change by winter tourists: some thoughts on consumer behavior research and an empirical example. Tourism Review 68(2), 44–55.

Pröbstl-Haider, U. and Haider, W. (2014) The Role of Protected Areas in Destination Choice in the European Alps. Zeitschrift für Wirtschaftsgeographie 58(2–3), 144–163.

Pröbstl-Haider, U., Mostegl, N.M. and Haider, W. (2015) Einfluss von Skigebietsverbindungen im Bereich Stubai/westliches Mittelgebirge auf die regionale und deutsche Nachfrage durch Wintersportler. Final Report. Available at: https://www.brueckenschlag-tirol.com/ (accessed 20 December 2018).

Pröbstl-Haider, U., Mostegl, N.M. and Haider, W. (2017) Panoramablick versus Pistenkilometer. Wichtige Kriterien bei der Buchung eines Skigebietes in Österreich. Tourismus Wissen – Quarterly 7, 34–40.

Reisinger, Y. and Turner, K. (2002) Cultural differences between Asian tourist markets and Australian hosts, Part 1. Journal of Travel Research 40(3), 295–315.

Reisinger, Y. and Turner, K. (2003) Cross-Cultural Behavior in Tourism. Butterworth-Heinemann, Oxford, UK.

Rose, J.M., Hensher, D.A., Caussade, S., de Dios Ortùzar, J. and Jou, R.-C. (2009) identifying differences in willingness to pay due to dimensionality in stated choice experiments: a cross country analysis. Journal of Transport Geography 17(1), 21–29.

Roth, R., Krämer, A. and Severins, J. (2018) Nationale Grundlagenstudie Wintersport Deutschland 2018. Stiftung Sicherheit im Skisport e.V., Cologne, Germany.

Rupf, R. (2015) Planungsinstrumente für Wandern und Mountainbiking in Berggebieten. Unter besonderer Berücksichtigung der Biosfera Val Müstair. Haupt, Bern, Switzerland.

Ryan, M. and Gerard, K. (2003) Using discrete choice experiments to value health care programmes: current practice and future research reflections. Applied Health Economics and Health Policy 2(1), 55–64.

Simpson, M.C., Gössling, S., Scott, D., Hall, C.M. and Gladin, E. (2008) Climate Change Adaptation and Mitigation in the Tourism Sector: Frameworks, Tools and Practices. UNEP, Paris.

Sorice, M.G., Oh, C.-O. and Ditton, R.B. (2005) Using stated preference discrete choice experiment to analyze scuba divers’ preferences for coral reef conservation. Final report prepared for the Coral Reef Competitive Grants Program of the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation. Available at: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/19540869.pdf (accessed 20 December 2018).

Steiger, R., Posch, E., Pons-Pons, M. and Vilella, M. (2017) Climate change impacts on skier behaviour and spatial distribution of skiers in Austria. Available at: https://www.ccca.ac.at/fileadmin/00_DokumenteHauptmenue/03_Aktivitaeten/Klimatag/Klimatag2017/Vortr%C3%A4ge/V48_Steiger.pdf (accessed 10 January 2019).

Triandis, H.C. (1972) The Analysis of Subjective Culture. Wiley-Interscience, Oxford, UK.

Turner, L.W., Reisinger, Y.V. and McQuilken, L. (2002) How cultural differences cause dimensions of tourism satisfaction. Journal of Travel and Tourism Marketing 11(1), 79–101.

Unbehaun, W., Haider, W. and Pröbstl, U. (2008) Trends in winter sport tourism: challenges for the future. Tourism Review 63(1), 36–47.

van Beukering, P., Haider, W., Longland, M., Cesar, H., Sablan, J. et al. (2007) The economic value of Guam’s coral reefs. University of Guam Marine Laboratory Technical Report No. 116. Available at: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/5519/843c40d0400afc958a2c163da7b518c68a36.pdf (10 January 2019).

Weiermair, K. (2000) Tourists’ perceptions towards and satisfaction with service quality in the cross-cultural service encounter: implications for hospitality and tourism management. Managing Service Quality 10(6), 397–409.

Zweifel, B. and Haegeli, P. (2014) A qualitative analysis of group formation, leadership and decision making in recreation groups traveling in avalanche terrain. Journal of Outdoor Recreation and Tourism 5–6, 17–26.