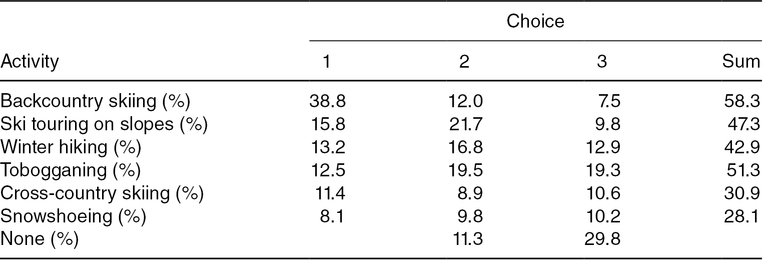

Table 20.1. Alternative outdoor activities practised (first, second and third choice) (n = 909).

20 Alternative Outdoor Activities in Alpine Winter Tourism

1Institute of Geography, University of Innsbruck, Innsbruck, Austria; 2Institute for Systemic Management and Public Governance, University of St. Gallen, St. Gallen, Switzerland; 3Department of Strategic Management, Marketing and Tourism, University of Innsbruck, Innsbruck, Austria

*E-mail: bruno.abegg@uibk.ac.at

Downhill skiing and snowboarding are the most popular winter sport activities in the European Alps. However, there is growing interest in activities other than skiing and snowboarding such as ski touring, snowshoeing and tobogganing. An increasing number of winter tourists combine skiing/snowboarding with these activities, or do not ski/snowboard at all (e.g. Dolnicar and Leisch, 2003; Bausch and Unseld, 2017). Winter sport destinations are investing significant amounts of money to diversify the snow-based offer and to appeal to people practising different activities.

There is an abundance of scientific literature on outdoor recreation in general, and on winter sport activities in particular (mostly focusing on skiing; e.g. Hudson et al., 2004; Matzler et al., 2007; Steiger et al., 2017), but little is known about winter sport activities other than skiing. Most of the existing literature on alternative activities focuses on medical and physiological aspects including, for example, biomechanics (e.g. Pellegrini et al., 2013) and injuries (e.g. Ruedl et al., 2017). In addition, there is some literature on risk, for example the risk of avalanches (e.g. Techel et al., 2015) or the risk propensity of outdoor recreationists (e.g. Marengo et al., 2017), and on the impact of alternative outdoor activities on nature and wildlife in protected or non-protected areas (e.g. Sato et al., 2013; Cremer-Schulte et al., 2017). Potential impacts of climate change on alternative winter sport activities, in particular cross-country skiing, have been researched as well (e.g. Pouta et al., 2009; Landauer et al., 2012; Neuvonen et al., 2015). Finally, there is scattered scientific information on topics such as the economic effects of alternative winter sport activities (e.g. McCollum et al., 1990; Filippini et al., 2017) and the potential conflicts between different types of alternative outdoor activities (e.g. Jackson and Wong, 1982; Vittersø et al., 2004).

The same is true when it comes to the question of the motivation to engage in outdoor activities: there is a wealth of information on tourists’ motivation in general, there are some studies dealing with the motivation of skiers and snowboarders (e.g. Unbehaun et al., 2008; Alexandris et al., 2009), but little is known about the motivation of the people practising alternative winter sport activities. Beier (2002), for instance, named ‘experiencing nature’, ‘improvement of health, fitness and/or performance’ and ‘social aspects’ as the most important motives for practising outdoor activities in Germany. Similarly, ‘experiencing scenic beauty and nature’, ‘recreation/relaxation’ and ‘wellness/fitness’ are most important for outdoor recreationists in Switzerland (Zeidenitz et al., 2007). However, these findings refer to a series of different outdoor activities that are neither restricted to winter nor to mountain activities. A closer look at specific activities, however, reveals some details. A comparison between two totally different activity groups, free-riders (off-piste skiers and snowboarders) and picnickers, shows a similar structure of motives: the top-ranked motives including recreation, nature, health/fitness and socializing, etc. are the same (although in a slightly different order) – the only exception being ‘adventure and thrill’, which is, unsurprisingly, significantly more important for free-riders than picnickers (Zeidenitz et al., 2007). Perrin-Malterre and Chanteloup (2018) focus on two selected alternative winter sport activities, backcountry skiing and snowshoeing, in the Hautes-Bauges region of Savoy (France). They mention a number of motives to practise these activities, namely ‘contact with nature’, ‘recharge one’s batteries’ and ‘escape from ski resorts’, and identify – based on multiple factor analysis – practitioner profiles ranging from ‘performers’ to ‘spiritualists’ (with most practitioners being somewhere in between). Finally, there are studies focusing on single activities only, for example on cross-country skiing or ski touring on slopes. Landauer et al. (2009) looked at the motivation of Finnish cross-country skiers. They applied principal component analysis to group the nine motives considered into three factors including ‘skiing environment’ (e.g. nature experience), ‘social features’ (e.g. time with family and friends) and ‘technical skills and fitness’ (e.g. keeping fit). Pröbstl-Haider and Lampl (2017), focusing on ski touring on slopes, surveyed outdoor recreationists from Austria and Germany and found ‘sport and exercise’, the ‘improvement of general health’ and the ‘escape from the daily routine’ to be the most important motives (among 12 motives in total).

In Tyrol (Austria), skiing and snowboarding are given top priority. But like elsewhere in the European Alps, winter activities other than skiing/snowboarding are gaining in importance, as are the numbers of people practising these activities. However, little is known about these people and their activities. For this book chapter, we focus on the six most popular alternative winter sport activities in Tyrol: backcountry skiing, ski touring on slopes (i.e. skiing up the hill on the fringe of groomed ski slopes), winter hiking, tobogganing, cross-country skiing and snowshoeing. More precisely, we want to explore the people’s activity profiles and their satisfaction with the existing offer in Tyrol. Special attention is given to the motivation to practise alternative winter sport activities.

To investigate this topic a standardized questionnaire was developed. The main focus of the questionnaire was on the performance of alternative winter sport activities (e.g. what kind of activities are performed, how frequent and with whom) and on the motivation to do so. Participants were asked what information sources they consulted to plan the activity, and what infrastructure they used to perform the activity. Experiences while performing the activity were another topic (e.g. satisfaction with the existing offer in Tyrol, suggestions to improve the existing offer and conflicts between different activities). Finally, general information such as gender, age, place of residence and guest type (day visitor or overnight guest) was collected. For the chapter at hand, we focus on the activities practised, the satisfaction and the motivation.

Besides multiple choice questions, 4- and 5-point Likert scales were used to measure the respondent’s satisfaction with the supply of alternative winter sport activities in Tyrol (1 ‘unsatisfied’ – 4 ‘satisfied’) and to evaluate the importance of motivational factors to perform these activities (1 ‘unimportant’ – 5 ‘important’). The motivation to perform alternative winter sport activities was measured with different items. The literature review (see above) revealed a high number of potentially important items. After a consultation process with several experienced winter sport enthusiasts, and after taking into account some practicability issues (i.e. items should be clearly distinguishable from each other; items should be relevant for all alternative winter sport activities investigated; survey participants cannot be asked to evaluate an infinite number of items), the number of items was reduced to 20.

Data collection took place at highly frequented locations (e.g. a parking lot at the starting of the cross-country network) in several Tyrolean destinations from mid-December 2017 to the end of March 2018. People were asked (if not obvious) whether they perform alternative winter sport activities and if they would like to participate in a research project. If they were willing, they were given a brief introduction to the project (content, methods and aims) and were asked for their e-mail addresses. Subsequently, the link to the online questionnaire (available in both German and English) was e-mailed to the participants. To boost participation in the survey, three gift vouchers were drawn among respondents who filled in the questionnaire completely.

A total of 1056 questionnaires were collected. After excluding incomplete questionnaires, a sample of 909 questionnaires remained for further analyses. Descriptive and analytical statistics were applied to explore the profile of the sample and to identify differences between subgroups (e.g. age, gender, guest and activity types). To further analyse the motivational items, a principal component analysis, using the varimax rotation with Kaiser normalization (Field, 2011; Tabachnick and Fidell, 2013), was conducted (see Landauer et al., 2009 and Konu et al., 2011 for similar applications of principal component analysis in snow-based tourism). As a cut-off point, a loading factor of 0.4 was set. To assess the internal reliability of each factor, Cronbach’s alpha was computed (Cortina, 1993). All statistical calculations were made in IBM SPSS 24 software.

There are slightly more male (52.5%) than female respondents in the sample. The average age is 39.2 years (median: 37 years) with the majority of respondents (61.1%) being between 31 and 60 years old. A total of 31.7% of the respondents are younger, 7.2% are older; 61.3% of the respondents are day visitors, 38.7% are overnight guests. Most respondents live in Austria (46.4%; thereof 39% in Tyrol), followed by Germany (43.5%), Switzerland (2.8%), The Netherlands (2.7%), the UK (2.1%) and Italy (0.7%).

Most respondents practise more than one winter sport activity. It is common to combine alternative winter sport activities with downhill skiing/snowboarding (76.5% of respondents) – although the time spent for each of the two categories varies greatly: 28.5% of the respondents indicate that they spend <20% of their overall winter sport time on skiing/snowboarding, whereas 25.5% of the respondents say that they spend >80% of their overall winter sport time on skiing/snowboarding. The percentage of respondents doing alternative winter sport activities only is therefore comparatively small (23.5%). The most popular alternative winter sport activities are backcountry skiing, followed by ski touring on slopes and winter hiking (first choice only, see Table 20.1).

The respondents like companionship, most preferably with friends and partner/family including kids; only 9.5% of the respondents practise on their own. Many respondents seem to be rather experienced: 77% of the respondents have been practising for >3 years, and more than half of the respondents (55.4%) spend at least 10 days per season performing the respective activities. In terms of activity choice, no differences can be detected between female and male respondents. Backcountry skiing, ski touring on slopes and tobogganing become less popular with increasing age; winter hiking, though, becomes more popular (p = 0.000). Snowshoeing and cross-country skiing are most popular with respondents aged between 31 and 60 years (p = 0.000). Day visitors predominantly practise backcountry skiing (and to lesser extent ski touring on slopes), overnight guests significantly more often choose winter hiking, cross-country skiing, tobogganing and snowshoeing (p = 0.000).

In general, the respondents seem to be very pleased with the existing offer (see Table 20.2). Even the lowest mean score is close to 3, which is remarkable given the scale from 1 (unsatisfied) to 4 (satisfied). Consequently, there are only a small number of respondents suggesting improvement measures. The highest number of respondents doing so (n = 266; 29.8%) call for better accessibility by public transport, followed by 183 respondents asking for larger parking lots. Notably, there are 245 respondents making no suggestions at all. With regard to the age of the respondents, no differences in the level of satisfaction can be detected. Female respondents are generally more satisfied with the existing offer than male respondents, particularly with the family-friendliness (p = 0.000), the available information material (p = 0.002), the night-time activities (p = 0.005), the rental services (p = 0.013) and the accessibility by public transport (p = 0.047). Day visitors are more satisfied with the variety of activities/tours, the information material and the night-time activities (all p = 0.000), overnight guests with the parking facilities, the accessibility by public transport (both p = 0.000) and the rental services (p = 0.001). Backcountry skiers are more satisfied with the variety of activities/tours (p = 0.000) and the information material (p = 0.009) than others (in particular than toboggan riders and cross-country skiers) but less satisfied with the parking facilities (p = 0.011) and the accessibility by public transport (p = 0.000). However, irrespective of the statistically significant differences between subgroups, the general satisfaction level is high.

20.3.2 MotivationTable 20.3 shows the ranking of the motivational items for the whole sample. Focusing on single activities, statistically significant differences in the importance can be found for almost all items (except for relieving stress and low cost). For the activity ‘ski touring on slopes’, for example, the item ‘belongs to individual training/workout schedule’ is more important than for all other activities (p = 0.000). And for toboggan riders, the items ‘experiencing action/adventure’ and ‘Hüttengaudi – fun in mountain huts’ are more important than for all others (both p = 0.000). In some cases, however, the differences in the importance of single items – although statistically significant – are rather small. For example, the mean value for ‘enjoying/experiencing nature’ varies only between 4.85 (highest for backcountry skiing) and 4.39 (lowest for tobogganing).

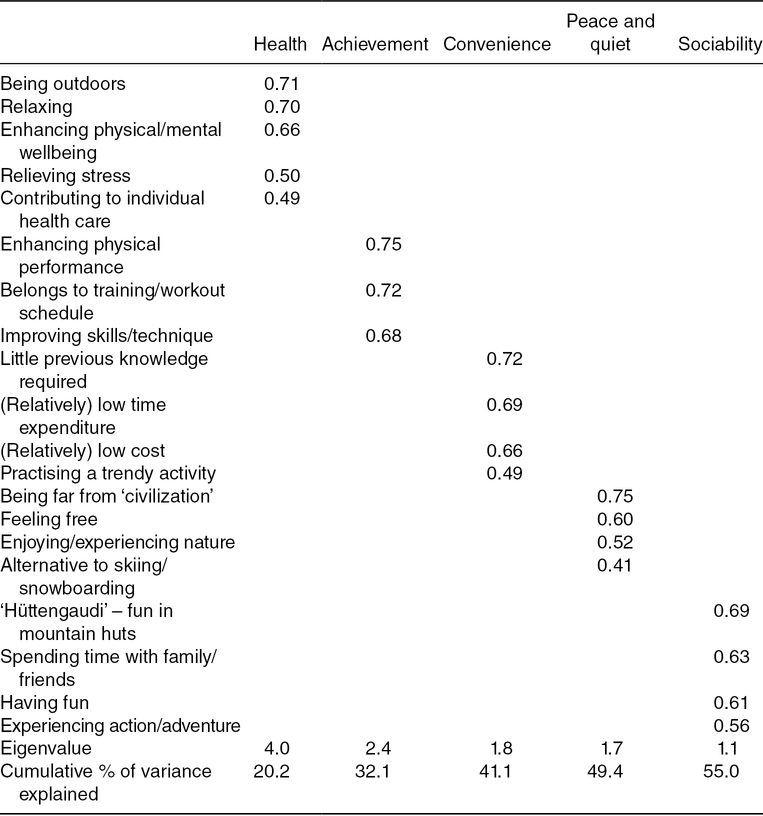

The principal component analysis produced a five-factor solution (see Table 20.4) with eigenvalues >1 representing 55.0% of the total variance of the variables. All items showed factor loadings >0.4, none of them loaded on multiple factors, therefore no item had to be removed. The internal consistency of the factors, measured with Cronbach’s alpha, showed good reliability with scores ranging from 0.557 to 0.693. The five factors can be described as follows:

• Factor 1 is made up of five items. It is about stress release and relaxation. Practising alternative winter sport activities (and simply being outdoors) contributes to physical and mental wellbeing. Therefore, this factor is called ‘health’.

• Factor 2 is made up of three items. It corresponds to physical exertion, fitness and skill; moreover, practising alternative winter sport activities is part of an individual training/workout schedule. Therefore, this factor is called ‘achievement’.

• Factor 3 is made up of four items. It is about the relatively ‘low barriers’ related to the performance of these activities: it is relatively low cost (at least in comparison to downhill skiing and snowboarding), it can be done in a relatively short period of time (i.e. it doesn’t take the whole day), and at least a few of the respective activities can be enjoyed with no/little previous knowledge and skill. Furthermore, it is trendy. Referring (mainly) to the first three items, this factor is called ‘convenience’.

• Factor 4 is made up of four items. It is about ‘feelings’, to be away from it all (i.e. ‘civilization’), to feel free and to enjoy nature. In addition, it is seen as an alternative to skiing and snowboarding on (crowded) slopes. Therefore, this factor is called ‘peace and quiet’.

• Factor 5 is made up of four items as well. It refers to fun and action/adventure, and to social aspects such as being with friends and family and having a good time in mountain huts. Therefore, this factor is called ‘sociability’.

Table 20.4. Principal component analysis of the motives to practise alternative winter sport activities.

These factors (‘bundle of motives’) are significantly more important to female respondents (p = 0.000–0.020), the exception being ‘sociability’ (not significant). The importance of ‘sociability’ (p = 0.000) and ‘peace and quiet’ (p = 0.026) decreases with increasing age. ‘Health’ is most important for respondents aged between 31 and 60 years (p = 0.000). ‘Health’, ‘achievement’ and ‘peace and quiet’ are deemed to be more important for day visitors, and ‘convenience’ and ‘sociability’ to be more important for overnight guests (all p = 0.000). Focusing on activities: ‘health’ is most important to winter hikers (least to toboggan riders), ‘achievement’ and ‘convenience’ to people ski touring on slopes (least to toboggan riders and backcountry skiers, respectively), ‘peace and quiet’ to backcountry skiers (least to cross-country skiers) and ‘sociability’ to toboggan riders (least to cross-country skiers) (all p = 0.000).

This research produced new insights: (i) ski touring on slopes is a relatively new phenomenon but it seems that the activity has become firmly established in Tyrol; (ii) outdoor recreationists are happy with the existing offer – this is definitely good news for the Tyrolean destinations; and (iii) the ranking of the motives (see Table 20.3) as well as the factors resulting from the principal component analysis (see Table 20.4) are not very surprising and confirm existing knowledge. Contrary to previous research, however, this analysis focuses on multiple activities, and the relatively large sample allows for a detailed analysis of different subgroups, be it, for example, activity types or visitor types. We can confirm that motives vary between activities, and we can characterize both the socio-demographic profile and the motives of outdoor recreationists practising particular activities. Tobogganing, for example, is not the favourite first choice activity but it is important as a secondary or tertiary activity. It is most popular with younger overnight guests seeking action and fun. Furthermore, there are significant differences between day visitors and overnight guests. Day visitors, for example, prefer backcountry skiing and ski touring on slopes, and they are driven by ‘peace and quiet’, ‘health’ and ‘achievement’. This is valuable information for destinations seeking to better understand their visitors, and it can be used for product offering, positioning and marketing.

The results presented here are an excerpt only. The dataset allows for further analysis, for example, by including the education of the respondents. Besides day visitors and overnight guests we could also distinguish between recreationists combining downhill skiing/snowboarding with alternative activities and recreationists practising alternative activities only. Moreover, it can be hypothesized that there are distinct outdoor types such as the ‘fitness freaks’ or the ‘pleasure seekers’, and a cluster analysis should be conducted to detect such outdoor types. This would contribute to an even clearer picture of the outdoor recreationists in Tyrol.

This research, however, is also subject to limitations. One limitation refers to the representativeness of the sample. Some aspects of the sample (e.g. age distribution and place of residence of the respondents) are in accordance with available data from Tyrol. Other aspects of the sample are more challenging: as there is no reliable information about, for example, the number of day visitors and the share of recreationists practising particular outdoor activities, it is difficult to assess the representativeness. Furthermore, the analysis is restricted to six popular alternative outdoor activities in Tyrol. There are additional activities such as snowmobiling, dog sledding and ice fishing. These activities are of less interest in Tyrol (and the European Alps) but much more important in North America and Scandinavia.

Most of the existing research on snow-based tourism focuses on downhill skiing. This is understandable given the past and current importance of skiing for many winter destinations. Downhill skiing, however, is challenged by climate change, demographics and competition from non-snow-based destinations. To investigate alternative outdoor activities in winter tourism is an important and promising scientific endeavour: it is under-researched, and it can be assumed that the topic will further gain in importance. Many winter sport destinations understand that there is much more to future winter tourism than downhill skiing.

The authors would like to thank Steve Borchardt and Alina Kuthe for their support in collecting the e-mail addresses (Steve) and conducting the principal component analysis (Alina). This research was funded by the Tourism Research Centre of Tyrol.

Alexandris, K., Kouthouris, C., Funk, D. and Giovani, C. (2009) Segmenting winter sport tourists by motivation: the case of recreational skiers. Journal of Hospitality Marketing and Management 18(5), 480–499. DOI:10.1080/19368620902950048

Bausch, T. and Unseld, C. (2017) Winter tourism in Germany is much more than skiing! Consumer motives and implications to alpine destination marketing. Journal of Vacation Marketing 24(3), 1–15. DOI:10.1177/1356766717691806

Beier, K. (2002) Was reizt Menschen an sportlicher Aktivität in der Natur? Zu den Anreizstrukturen von Outdoor-Aktivitäten. In: Dreyer A. (ed.) Tourismus und Sport. Harzer wirtschaftswissenschaftliche Schriften. Deutscher Universitätsverlag, Wiesbaden, Germany, pp. 81–92.

Cortina, J. (1993) What is coefficient alpha? An examination of theory and applications. Journal of Applied Psychology 78(1), 98–104.

Cremer-Schulte, D., Rehnus, M., Duparc, A., Perrin-Malterre, C. and Arneodo, L. (2017) Wildlife disturbance and winter recreational activities in alpine protected areas: recommendations for successful management. eco-mont 9(2), 66–73.

Dolnicar, S. and Leisch, F. (2003) Winter tourist segments in Austria – identifying stable vacation styles using bagged clustering techniques. Journal of Travel Research 41(3), 281–292.

Field, A. (2013) Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics, 4th edn. Sage, Los Angeles, California.

Filippini, M., Greene, W. and Martinez-Cruz, A.L. (2017) Non-market value of winter outdoor recreation in the Swiss Alps: The case of Val Bedretto. Environmental and Resource Economics 71(3), 729–754. DOI:10.1007/s10640-017-0181-0

Hudson, S., Ritchie, B. and Timur, S. (2004) Measuring destination competitiveness: an empirical study of Canadian ski resorts. Tourism and Hospitality Planning and Development 1(1), 79–94. DOI:10.1080/1479053042000187810

Jackson, E.L. and Wong, R.A.G. (1982) Perceived conflict between urban cross-country skiers and snowmobilers in Alberta. Journal of Leisure Research 14(1), 47–62. DOI:10.1080/00222216.1982.11969504

Konu, H., Laukkanen, T. and Komppula, R. (2011) Using ski destination choice criteria to segment Finnish ski resort customers. Tourism Management 32(5), 1096–1105. DOI:10.1016/j.tourman.2010.09.010

Landauer, M., Sievänen, T. and Neuvonen, M. (2009) Adaptation of Finnish cross-country skiers to climate change. Fennia 187(2), 99–113.

Landauer, M., Pröbstl, U. and Haider, W. (2012) Managing cross-country skiing destinations under the conditions of climate change – scenarios for destinations in Austria and Finland. Tourism Management 33(4), 741–751. DOI:10.1016/j.tourman.2011.08.007

Marengo, D., Monaci, M.G. and Miceli, R. (2017) Winter recreationists’ self-reported likelihood of skiing backcountry slopes: investigating the role of situational factors, personal experiences with avalanches and sensation-seeking. Journal of Environmental Psychology 49, 78–85. DOI:10.1016/j.jenvp.2016.12.005

Matzler, K., Füller, J. and Faullant, R. (2007) Customer satisfaction and loyalty to alpine ski resorts: the moderating effect of lifestyle, spending and customers’ skiing skills. International Journal of Tourism Research 9(6), 409–421. DOI:10.1002/jtr.613

McCollum, D.W., Gilbert, A.H. and Peterson, G.L. (1990) The net economic value of day use cross country skiing in Vermont: a dichotomous choice contingent valuation approach. Journal of Leisure Research 22(4), 341–352. DOI:10.1080/00222216.1990.11969839

Neuvonen, M., Sievänen, T., Fronzek, S., Lahtinen, I., Veijalainen, N. and Carter, T.R. (2015) Vulnerability of cross-country skiing to climate change in Finland – an interactive mapping tool. Journal of Outdoor Recreation and Tourism 11, 64–79. DOI:10.1016/j.jort.2015.06.010

Pellegrini, B., Zoppirolli, C., Bortolan, L., Holmberg, H.C., Zamparo, P. and Schena, F. (2013) Biomechanical and energetic determinants of technique selection in classical cross-country skiing. Human Movement Science 32(6), 1415–1429. DOI:10.1016/j.humov.2013.07.010

Perrin-Malterre, C. and Chanteloup, L. (2018) Ski touring and snowshoeing in the Hautes-Bauges (Savoie, France): a study of various sports practices and ways of experiencing nature. Journal of Alpine Research/Revue de géographie alpine 106-4. DOI:10.4000/rga.3934

Pouta, E., Neuvonen, M. and Sievänen, T. (2009) Participation in cross-country skiing in Finland under climate change: application of multiple hierarchy stratification perspective. Journal of Leisure Research 41(1), 92–109.

Pröbstl-Haider, U. and Lampl, R. (2017) Skitourengeher auf Pisten – Überlegungen zur Produktentwicklung für eine neue touristische Zielgruppe. In: Roth, R. and Schwark, J. (eds) Wirtschaftfaktor Sporttourismus. Erich Schmidt Verlag, Berlin, Germany, pp. 207–214.

Ruedl, G., Pocecco, E., Raas, C., Brucker, P.U., Greier, K. and Burtscher, M. (2017) Unfallursachen und Risikofaktoren bei erwachsenen Rodlern: eine retrospektive Studie (Causes of accidents and risk factors among adults during recreational sledging (tobogganing): a retrospective study). Sportverletzung Sportschaden 31(1), 45–49.

Sato, C.F., Wood, J.T. and Lindenmayer, D.B. (2013) The effects of winter recreation on alpine and subalpine fauna: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 8(5), e64282. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0064282

Steiger, R., Scott, D., Abegg, B., Pons, M. and Aall, C. (2017) A critical review of climate change risk for ski tourism. Current Issues in Tourism, 1–37. DOI:10.1080/13683500.2017.1410110

Tabachnick, B.G. and Fidell, L.S. (2013) Using Multivariate Statistics, 6th edn. Pearson, Harlow, UK.

Techel, F., Zweifel, B. and Winkler, K. (2015) Analysis of avalanche risk factors in backcountry terrain based on usage frequency and accident data in Switzerland. Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences 15, 1985–1997. DOI:10.5194/nhess-15-1985-2015

Unbehaun, W., Pröbstl, U. and Haider, W. (2008) Trends in winter sport tourism: challenges for the future. Tourism Review 63(1), 36–47.

Vittersø, J., Chipeniuk, R., Skår, M. and Vistad, O.I. (2004) Recreational conflict is affective: the case of cross-country skiers and snowmobiles. Leisure Sciences 26(3), 227–243. DOI:10.1080/01490400490461378

Zeidenitz, C., Mosler, H.J. and Hunziker, M. (2007) Outdoor recreation: from analysing motivations to furthering ecologically responsible behaviour. Forest Snow and Landscape Research 81(1/2), 175–190.