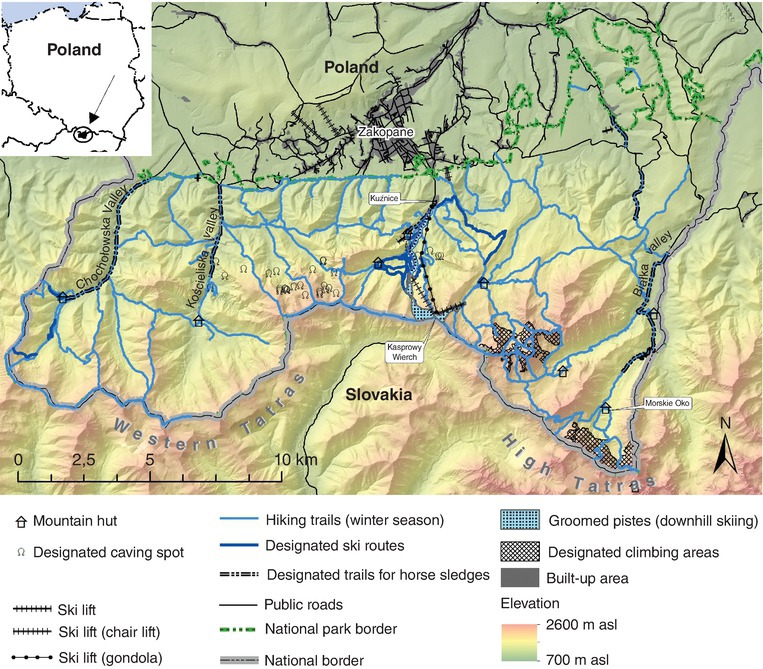

Fig. 21.1. Areas designated for winter outdoor recreation located within the border of the Tatra National Park.

21 Winter Tourism Management and Challenges in the Tatra National Park

1Institute of Landscape Development, Recreation and Conservation Planning, University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences, Vienna, Austria; 2Faculty of Tourism and Leisure, University of Physical Education in Kraków, Kraków, Poland; 3Department of Tourism and Health Resort Management, Institute of Geography and Spatial Management, Jagiellonian University, Kraków, Poland; 4Department of Physical Geography, Institute of Geography and Spatial Management, Jagiellonian University, Kraków, Poland; 5Tatra National Park, Zakopane, Poland

*E-mail: karolina.taczanowska@boku.ac.at

The Tatra Mountains belong to the list of the most popular tourist destinations in the Carpathian Mountains and attract large numbers of visitors throughout the year. Although most of the visitors arrive here in the summer months, the winter season attracts a more heterogeneous visitor profile, which on the one hand contributes to the diversification of tourist offerings, but on the other, poses multiple challenges to area management.

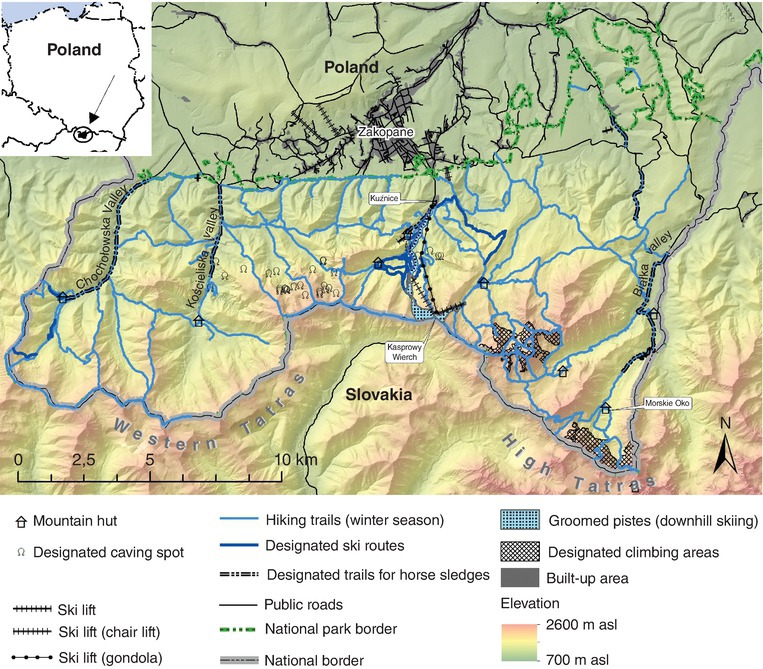

This chapter is based upon studies carried out in the Tatra National Park (TNP) located in Poland, Central Eastern Europe. The national park was established in 1954 (TNP, 2018) and belongs to International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) management category II, which implies nature conservation along with provisioning a foundation for environmentally and culturally compatible recreation opportunities (Dudley, 2013). Visits to TNP, in the past 5 years, ranged from 2.9 to 3.8 million tourist visits a year (TNP, 2018), which considering the rather small area of the national park (212 km2) resulted in a visitor density of 137–179 visits/ha/year. Winter season typically lasts from the beginning of December till the end of April and accounts for approximately 14% of the total annual visitor load (TNP, 2018). Recreational use is permitted only in designated areas (see Fig. 21.1). The most popular outdoor recreation activities in winter are hiking and downhill skiing. Climbing and caving, in spite of having a long tradition in the area, are less fashionable winter activities. Ski touring, which was quite popular in the first half of the 20th century, now is rapidly developing after several decades of being almost absent from the TNP. Figure 21.2 illustrates frequencies and shares of outdoor activities performed in the winter season in TNP (TNP, 2018).

Fig. 21.1. Areas designated for winter outdoor recreation located within the border of the Tatra National Park.

Fig. 21.2. Outdoor recreation activities performed in the Tatra National Park in the winter months of 2017 (January, February, March, April and December 2017). (Chart based on data obtained from TNP, 2018.)

Provisioning environmentally compatible recreation opportunities in popular mountain destinations is one of the major managerial issues in many protected areas worldwide (Manning and Anderson, 2012; Newsome et al. 2012; Dudley, 2013; Richins and Hull, 2016). Recreation zoning, accompanied by strategic allocation of tourist infrastructure and sustainable tourism marketing are required management measures in protected areas (Eagles et al. 2002; Manning and Anderson, 2012; Newsome et al., 2012). This strategy applies also to the TNP, where general usage rules (see Fig. 21.1), which are supposed to be an integral part of the national park conservation plan (in TPN’s case still under preparation) and detailed regulations considering specific recreational activities are created by decrees issued by the director of the Tatra National Park (TNP, 2017). According to the Polish Nature Conservation Act 2004 (Sejm of the Republic of Poland, 2004), the major goal of a national park is nature protection, and such a protected area can be used for tourism and recreation only in ways that do not pose a threat to its natural resources. However, the system of recreational infrastructure and recreational use in the Tatra Mountains has a longer usage history than the protected area itself. The earliest marked trails and mountain huts dedicated to tourists originated in the 19th century and have developed over subsequent years. The first ski tours were documented in 1894. Ski competitions in the Tatras have taken place since 1907 (Paryski and Paryska, 1995). A cable car from Kuźnice to Kasprowy Wierch was constructed in 1936 (18 years before the formal designation of the Tatra National Park as a national park). The cable car project initiated by the Polish Ski Association and Ministry of Transportation was a topic of severe debate and at that time the National Nature Conservation Council (Państwowa Rada Ochrony Przyrody) along with 94 scientific institutions and tourist associations were against cable car infrastructure being located in the Tatra Mountains. This development attracted further investments, such as the construction of the meteorological observatory at Kasprowy Wierch and a hotel at Kalatówki near Kuźnice.

In the first decades after designation of the Tatra National Park (1954) several zones, located in the most ecologically precious parts of the park, were closed to recreational use. Also, in the 1980s, limestone cliffs, with diverse vegetation, were excluded from climbing use. Currently, in the winter season 259 km of marked trails are open for hiking and ski touring. Ski tourers can also legally use several additional routes dedicated to skiing (see Fig. 21.1). Most granite cliffs are open for climbing and 21 caves are accessible in the winter season. In 2018, several routes in the high-mountain zone within the cliffs and along gullies were additionally designated for ski-alpinism (extreme downhill skiing). Moreover, the ski resort Kasprowy Wierch (1027–1959 masl) offers a cable car and two ski lifts accompanied by 14.1 km of groomed ski pistes and two groomed slopes above the timberline. A few more small ski lifts operate on short pistes on the periphery of the TPN.

Finding the right balance between concentrating versus dispersing recreational use is a topical theme in the ongoing protected area management discourse.

Delineating recreation areas and designing rules for protected areas should be accompanied by systematic visitor monitoring (Cessford and Muhar, 2003; Arnberger et al., 2005). Comprehensive data on recreational use allow us to better assess compliance with nature protection objectives and to gauge the social function of protected areas. Systematically acquired data on visitation level, type of activities, spatial distribution and also socio-demographic profiles of visitors can greatly support management decisions. Long-term monitoring strategies are especially valuable. Thus, changing politics, societies, lifestyles and environmental conditions may contribute to changes in visitor preferences and behaviour.

In the TNP a systematic register of visits, based on tickets sold at major national park trailheads has been conducted since 1993. Additionally, data on cable car transfers are shared with TNP management by the cable car operator. Moreover, climbing and caving activities are reported to the TNP by participating visitors (self-registration in a dedicated website or in a traditional climbing ascent book). As mentioned before, ski touring is a growing outdoor activity in the Tatras. A rapid increase in ski touring has been observed within the past decade. Systematic counting of ski tourers (done at ticket points located at major entries to the national park) was introduced in 2013. Visitor counting data are aggregated by day, month and year. Annual statistics comprise the period between January and December. So far, there is no routine reporting on an entire winter season (stretched over 2 calendar years), which makes comparisons between winter seasons in the TNP more difficult. However, in future, monthly figures could be aggregated also by season.

In addition to systematic visitor counting, studies concerning more detailed tourism aspects are being carried out. They comprise: visitor counting and/or surveys at specific locations of interest, e.g. the areas of highest visitation levels such as Morskie Oko, Kasprowy Wierch, Hala Gąsienicowa, etc. (Ziemilski and Marchlewski, 1964; Czochański and Szydarowski, 2000; Czochański, 2002; Taczanowska et al., 2016); or other current management issues, e.g. a TNP visitor survey concerning the potential inclusion of an insurance fee within a national park entry ticket price. The spatial distribution of visitors within the trail network and outside of the designated areas is being studied within the framework of dedicated research projects, e.g. a study on ski touring (Bielański, 2013; Bielański et al., 2018).

Currently, neither systematic visitor surveys, nor spatio-temporal distribution studies are being carried out in the TNP. Notably, field studies concerning the winter season are more difficult to carry out, due to the demanding outdoor conditions.

Outdoor recreation activities over the winter largely depend on constructed infrastructure, such as the cable car and ski lifts in the Kuźnice-Kasprowy Wierch area, or maintained access roads to mountain huts, e.g. the trail to Morskie Oko in the Białka Valley, the trail to Kalatówki or Kościeliska Valley. Easy access, and huts with warm food and drinks, encourage a high concentration of visitors at specific locations. The most frequently used starting point of winter trips to the TNP is Kuźnice, with multiple attracting outdoor activities: downhill skiing, hiking, climbing and ski touring. Kuźnice attracts 42% of the total winter visits to the TNP, whereas visits by cable car to Kasprowy Wierch account for nearly one-third (31%) of the total winter tourism traffic in the TNP (TNP, 2018a). Interestingly, groomed pistes, originally dedicated to downhill skiing, appeal also to other user groups. Recent studies showed an increased interest in using groomed ski slopes by ski tourers for both ascents and descents (Bielański et al., 2018). In winter 2013, 68% of ski tours started at the Kuźnice trailhead and the highest concentration of ski touring routes was observed on the groomed ski pistes (Bielański et al., 2018).

The second most heavily used TNP destination in the winter season is Białka Valley. A 9-km-long broad and rather easy trail, leading to a picturesque (frozen and snow-covered) lake ‘Morskie Oko’, attracts a large number of winter strollers and hikers (23% of the total winter visitor load). Additional motivation for some visitors might be the possibility of using traditional horse sledges (or horse carriages in case of insufficient snow cover) to shorten the hike. Similar opportunities are being offered in the frequently visited Kościeliska and Chochołowska valleys. The Chochołowska Valley is mostly private land so night sleigh rides with torches, forbidden on state lands, are becoming more and more popular every year here (so far they are not properly monitored by national park authorities).

Although the Tatra Mountains are acknowledged for their natural value, the visitor numbers indicate the dependence of winter tourism on constructed infrastructure. Therefore, decisions concerning further development of tourist infrastructure inside the protected area should be carefully considered. Existing built objects may require further renovation or development in the future, which may result in an increase of visitation level and concomitant impact on the natural environment. In the TNP there is an ongoing discussion concerning the development of the ski resort. Regularly, ideas suggesting constructing new tunnels, lifts, a water reservoir for artificial snowmaking, and increasing the cable car and ski lifts capacities are being posed by tourism and the ski industry.

Although, the large majority of winter tourists in the TNP choose infrastructure-dependent destinations and activities, there are also visitors seeking contact with ‘pure’ mountain environments. Hiking along marked trails in upper elevations, winter climbing and caving belong to traditional winter outdoor activities in the Tatra Mountains. Within the past 15 years, the rapid increase of ski touring has been noticed in the Tatras, reaching approximately 10,000 visits per year (Bielański, 2013). This activity, although very popular in the European Alps, Scandinavia and North America, has arrived rather late to the Carpathian Mountains and has spread out promptly bringing new challenges to mountain protected areas. Only recently have clear regulations concerning ski touring and monitoring of ski touring entries been introduced by the TNP management (TNP, 2017).

Among the major challenges concerning the management of the spatially unconstrained winter outdoor activities is usage outside of the designated recreation zones. In contrast to infrastructure-dependent outdoor activities, which allow wildlife habituation (Yarmoloy et al., 1988; Miller et al., 2001), faunal species cannot easily adapt to unexpected human disturbances occurring off-trail (Geist, 1978; Miller et al., 2001). Especially in the case of ski touring, the freedom of movement in snow-covered terrain encourages off-trail use. A recent GPS tracking study shows that, on average, 15% of the registered ski tourers’ GPS trackpoints were located off-trail (Bielański et al., 2018) and the off-trail behaviour varies among different locations in TNP. For instance, in the surroundings of the Chochołowska and Kościeliska Valleys, off-trail usage was significantly higher than in the Kuźnice–Kasprowy Wierch region (Bielański et al., 2018). Also, in the surroundings of the ski resort Kasprowy Wierch, side-country recreation outside ski field boundaries among downhill skiers and snowboarders is being observed. Between 2001 and 2007 the area intensively used by skiers outside of designated pistes expanded from 53 ha to 130 ha (Zwijacz-Kozica, 2007). This may be attributed not only to the higher popularity of powder skiing, but also to advances in equipment technology – the most popular skis have become shorter, wider and lighter, thus more suitable for off-piste skiing. Illegal climbing activity upon the limestone cliffs is also under observation. The number of climbers depends on weather and snow conditions, but usually does not exceed a few dozen ascents (Jodłowski, 2015). During the winter season, protection of several sensitive species of wildlife, including chamois (Rupicapra rupicapra tatrica), marmot (Marmota marmota latirostris) and black grouse (Tetrao tetrix) has become an important objective for the park management. Similar problems have been reported in other winter tourism destinations worldwide (Sterl et al., 2006; Freuler and Hunziker, 2007; Braunisch et al., 2011; Rupf et al., 2011; Coppes and Braunisch, 2013; Arlettaz et al., 2015).

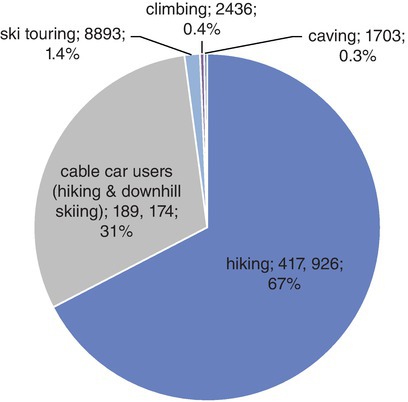

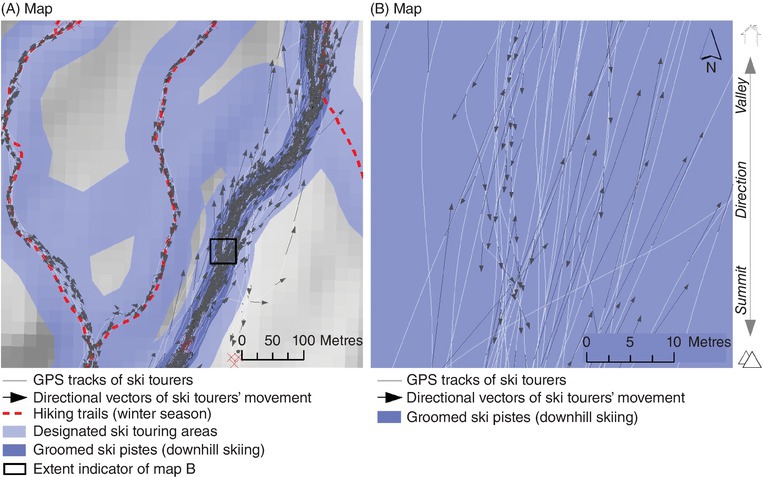

High concentrations of tourism at specific destinations can cause conflicts among visitors – especially, when recreation activities on offer and visitor expectations differ. There are many examples showing conflicting visitor expectations in winter tourism worldwide (Olson et al., 2017; Pröbstl-Haider and Lampl, 2017). Also in the Tatra Mountains user conflicts exist, however they are not sufficiently investigated. One potential source of conflict might be overcrowding in popular TNP destinations (e.g. Morskie Oko, Kasprowy Wierch and the Kościeliska Valley). Additional problematic cases arise with the spatial co-existence of multiple activity types. Several designated trails may be used by diverse user groups such as hikers, ski tourers and tourists travelling by horse sledge. Groomed ski pistes are being used by some ski tourers while ascending. Different speeds of movement and user expectations may contribute to the dissatisfaction of some visitors and may also pose a safety issue. Figure 21.3 illustrates the movement directions of ski tourers in the surroundings of the Kasprowy Wierch Ski Resort. Map B (see Fig. 21.3) exposes opposing movement directions of visitors within the border of the groomed ski piste, which may be a cause of user conflicts. This issue should be carefully investigated in the future, as the number of ski tourers is growing and Kuźnice is the most popular starting point of winter outdoor activities in the TNP.

Fig. 21.3. Movement direction of ski tourers, based on a smaller sample of visitors (GPS tracks collected on 16 March 2013). (A) Selected extent of Kuźnice–Kasprowy Wierch region showing ski touring ascents along hiking trails and most of the descents on the groomed downhill ski pistes. (B) Opposing movement directions as potential user conflict on the groomed ski pistes. (Reprinted from Bielański et al., (2018) Application of GPS tracking for monitoring spatially unconstrained outdoor recreational activities in protected areas – a case study of ski touring in the Tatra National Park, Poland. Applied Geography 96, 51–65, with permission from Elsevier.)

Risk and safety management is one of the major issues in mountain outdoor recreation management (Stethem et al., 2003; Höller, 2017; Pfeifer et al., 2018). Polish law designates that the director of the national park is the body responsible for implementing safety rules and regulations within the park (Sejm of the Republic of Poland, 2004). Thence, according to the TNP regulations, visitors take responsibility for their own actions and need to assess the conditions and are culpable for their decisions. Moreover, 15% of the yearly TNP income from ticket sales is redirected to subsidize the Tatra Mountain Rescue Service (Tatrzańskie Ochotnicze Pogotowie Ratunkowe (TOPR). TOPR is responsible for preparing and announcing daily avalanche reports. (TOPR, 2018a). Moreover, TOPR’s duties include mountain rescue within the TNP, including the ski resort Kasprowy Wierch. In 2017 there were 848 tourists rescued in the Tatra National Park, which accounts for 0.02% of the annual visitor load. Among rescued visitors there were 749 hikers, 60 downhill skiers, 6 snowboarders, 3 free-riders, 29 ski tourers, 30 climbers and 2 cavers. In 2017 TOPR reported 14 fatal accidents (2%), 36% serious injuries and 63% light injuries among visitor rescues. In 2017 there were 5 accidents caused by an avalanche, which affected 3 hikers, 1 ski tourer and 1 climber; there were no fatal avalanche accidents (TOPR, 2018b, 2018c).

One of the important aims of the TNP management is raising the awareness and safety of visitors concerning risks and safety issues related to winter outdoor activities. Therefore, since 2011 the TNP has organized the information campaign ‘Avalanche ABC’. At the weekends TNP visitors can participate in avalanche safety training (free of charge) and also use avalanche safety equipment at the Kalatówki Mountain Hotel, located near Kuźnice. Additionally, there are regular demonstrations of an avalanche airbag system, thematic lectures and meetings. In the winter season 2016/17 more than 400 tourists participated in training offered within the programme. Moreover, the TNP offered educational trips to students of local schools (24 guided trips in the winter season 2016/17). The initiative was also active on social media and the internet, promoting the programme and avalanche safety quizzes, where eight winners took part in an extensive avalanche safety training (Lawinowe ABC, 2017). The information campaign included the distribution of paper flyers with basic avalanche safety information. Moreover, at major trailheads of the TNP (Kuźnice, Hala Gąsienicowa, Palenica Białczańska, Huciska) avalanche transceiver ‘checkpoints’ have been installed, in order to test the functionality of visitors’ own devices.

To increase the safety of winter visitors the avalanche warning signs are placed along the trails where the trail enters a higher avalanche risk zone (e.g. couloir crossings, or at entry points to steeper terrain). Furthermore, avalanche risk information and the current warning level is displayed at each entry point and at the mountain huts.

Interestingly, participation in commercial trainings related to winter tourism and avalanche safety (offered by TOPR, the Polish Mountaineering Association, mountain guides, etc.) has significantly increased in recent years and currently reaches about 1000 participants per year.

As the Tatra Mountains are the only alpine area in Poland, the general public’s awareness of mountain risks is rather low. Therefore, further, continuous information campaigns highlighting mountain risks and promoting responsible behaviour in winter conditions are necessary to raise awareness among TNP visitors.

Protected areas try to fulfil the challenging mission of protecting nature and at the same time getting societal support for their actions (Dudley, 2013). Sometimes nature protection objectives and measures do not go along with the expectations of local inhabitants, interest groups or visitors to sites of exceptional natural value (Eagles et al., 2002). The TNP is facing a similar problem trying to balance the needs of people and site capacities. One of the major challenges of the national park is a lack of a significant formal buffer zone, allowing local land owners and municipality intensive urban or tourist infrastructure development along most of the border to the protected area. This creates a certain tension and conflicts of interest. Recently, also larger ideas, potentially having a severe impact on nature, were discussed. The Polish Olympic Committee posed the idea of holding the 2022 Winter Olympics in Kraków, with the majority of sport facilities located in the Tatras and its surroundings. In 2014 the inhabitants of Kraków voted to withdraw the bid in a binding referendum. However, similar initiatives of local and/or national authorities appear regularly and pose serious threats for nature conservation.

Over many years the TNP has run numerous educational and PR campaigns promoting the idea and necessity of nature protection among local inhabitants (mostly school children) and tourists. However, the attitudes towards nature protection vary quite a lot between people. A recent study on travel motives of tourists in the most popular TNP winter destination – Kasprowy Wierch – showed large heterogeneity in motives for visiting (Hibner and Taczanowska, 2016). Cluster analysis conducted among the ski slope users has shown that more than half of the respondents were more sport- or fun-oriented than nature-oriented. Furthermore, a large percentage of visitors expressed their negative opinions on the functioning of the ski resort. Most of them related to the lack of artificial snow or the limited number of ski pistes in the TNP. It is worth educating these segments of skiers in terms of nature-friendly behaviour and explaining the necessity of the introduced limitations. About one-third of ski slope users (28%) belong to the nature-oriented segment. This group of visitors appreciated contact with nature and mountain scenery and was reluctant to see new ski infrastructure in the TNP (Hibner and Taczanowska, 2016).

There is a need for further studies concerning environmental awareness and the actual behaviour of all visitor groups, local inhabitants and key stakeholders. Especially desirable would be the application of participatory methods allowing direct contact with interest groups and other stakeholders.

Winter season in the Tatra National Park, despite smaller visitor numbers due to a more heterogeneous visitor profile, poses many management challenges. Recreational systems that have been developed over decades since the 19th century need to be confronted with the current needs and expectations of visitors and the objectives of nature protection. The TNP has developed the systematic monitoring of visitor entries; however, in order to have a full picture of use within the protected area and social characteristics of visitors, additional regular studies are desirable. Especially, interdisciplinary approaches to recreation ecology linking founded ecological methods with social science approaches could be beneficial for protected area management. There is additionally a need to extend knowledge on inhabitants’ and tourists’ environmental awareness, awareness of mountain risks and knowledge of safety rules in winter mountainous environments. Regular information campaigns, cooperation with various user groups such as representatives of new activity trends while co-designing the TNP regulations are best-practice examples of protected area management. Current development trends need to be carefully observed in order to support proactive decision making to maintain the unique natural value of the highest part of the Carpathian Mountains.

Arlettaz, R., Nusslé, S., Baltic, M., Vogel, P., Palme, R. et al. (2015) Disturbance of wildlife by outdoor winter recreation: allostatic stress response and altered activity-energy budgets. Ecological Applications: A Publication of the Ecological Society of America 25(5), 1197–1212.

Arnberger, A., Haider, W. and Brandenburg, C. (2005) Evaluating visitor-monitoring techniques: a comparison of counting and video observation data. Environmental Management 36(2), 317–327.

Bielański, M. (2013) Skitouring in Tatra National Park and its environmental impacts. PhD Thesis, University School of Physical Education, Kraków, Poland.

Bielański, M., Taczanowska, K., Muhar, A., Adamski, P., González, L.-M. et al. (2018). Application of GPS tracking for monitoring spatially unconstrained outdoor recreational activities in protected areas – a case study of ski touring in the Tatra National Park, Poland. Applied Geography 96, 51–65. DOI:10.1016/j.apgeog.2018.05.008

Braunisch, V., Patthey, P. and Arlettaz, R. (2011) Spatially explicit modeling of conflict zones between wildlife and snow sports: prioritizing areas for winter refuges. Ecological Applications 21(3), 955–967. DOI:10.1890/09-2167.1

Cessford, G. and Muhar, A. (2003) Monitoring options for visitor numbers in national parks and natural areas. Journal for Nature Conservation 11(4), 240–250. DOI:10.1078/1617-1381-00055

Coppes, J. and Braunisch, V. (2013) Managing visitors in nature areas: where do they leave the trails? A spatial model. Wildlife Biology 19(1), 1–11. DOI:10.2981/12-054

Czochański, J. (2002) Ruch turystyczny w Tatrzańskim Parku Narodowym. In: Partyka, J. (ed.) Uźytkowanie turystyczne parków narodowych. Ojców, Poland, pp. 385–403.

Czochański, J. and Szydarowski, W. (2000) Diagnoza stanu i zróżnicowanie przestrzenno-czasowe użytkowania szlaków turystycznych w TPN. In: Borowiak, D. and Czochański, J. (eds) Z badań geograficznych w Tatrach Polskich. Wyd, UG, Gdańsk, Poland, pp. 207–228.

Dudley, N. (2013) Guidelines for Applying Protected Area Management Categories (IUCN). IUCN, Gland, Switzerland. Available at: https://www.iucn.org/sites/dev/files/import/downloads/iucn_assignment_1.pdf (accessed 30 January 2019).

Eagles, P.F.J., McCool, S.F. and Haynes, C.D. (2002) Sustainable Tourism in Protected Areas: Guidelines for Planning and Management. IUCN, Gland, Switzerland.

Freuler, B. and Hunziker, M. (2007) Recreation activities in protected areas: bridging the gap between the attitudes and behaviour of snowshoe walkers. Forest Snow and Landscape Research 81(1–2), 191–206.

Geist, V. (1978) Behavior. In: Schmidt, J.L. and Gilbert, D.L. (eds) Big Game of North America: Ecology and Management. Stackpole Books, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, pp. 283–296.

Hibner, J. and Taczanowska, K. (2016) Segmentation of alpine downhill skiers and snowboarders in mountain protected areas based on motivation factors: a comparison between two skiing areas: Kasprowy Wierch area (TPN, Poland) and Skalnaté Pleso area (TANAP, Slovakia). In: Vasiljevic, D. (ed.) MMV 8 Abstract Book. Faculty of Sciences, Department of Geography, Tourism and Hotel Management, Novi Sad, Serbia, pp. 366–368.

Höller, P. (2017) Avalanche accidents and fatalities in Austria since 1946/47 with special regard to tourist avalanches in the period 1981/82 to 2015/16. Cold Regions Science and Technology 144, 89–95. DOI:10.1016/j.coldregions.2017.06.006

Jodłowski, M. (2015) Nowa koncepcja zarządzania ruchem wspinaczkowym w Tatrzańskim Parku Narodowym jako sposób ograniczenia wpływu taternictwa na środowisko. In: Przyroda Tatrzańskiego Parku Narodowego a Człowiek. Tom III Człowiek i Środowisko. Wydawnictwa Tatrzańskiego Parku Narodowego, Zakopane, Poland, pp. 63–72.

Lawinowe ABC (2017) Lawinowe ABC (Avalanche ABC). Available at: www.lawinoweabc.pl (accessed 30 January 2019).

Manning, R.E. and Anderson, L.E. (eds) (2012) Managing Outdoor Recreation: Case Studies in the National Parks. CAB International, Wallingford, UK. DOI:10.1079/9781845939311.0000

Miller, S.G., Knight, R.L. and Miller, C.K. (2001) Wildlife Responses to Pedestrians and Dogs. Wildlife Society Bulletin (1973–2006) 29(1), 124–132.

Newsome, D., Moore, S.A. and Dowling, R.K. (2012) Natural Area Tourism: Ecology, Impacts and Management. Channel View Publications, Clevedon, UK.

Olson, L.E., Squires, J.R., Roberts, E.K., Miller, A.D., Ivan, J.S. et al. (2017) Modeling large-scale winter recreation terrain selection with implications for recreation management and wildlife. Applied Geography 86, 66–91. DOI:10.1016/j.apgeog.2017.06.023

Paryski, W.H. and Paryska, Z. (1995) Wielka Encyklopedia Tatrzańska. Wydawnictwo Górskie, Poronin, Poland.

Pfeifer, C., Höller, P. and Zeileis, A. (2018) Spatial and temporal analysis of fatal off-piste and backcountry avalanche accidents in Austria with a comparison of results in Switzerland, France, Italy and the US. Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences 18(2), 571–582. DOI:10.5194/nhess-18-571-2018

Pröbstl-Haider, U. and Lampl, R. (2017) From conflict to co-creation: ski-touring on groomed slopes in Austria. In: Correia, A., Kozak, M., Gnoth, J. and Fyall, A. (eds) Co-Creation and Well-Being in Tourism. Springer, Cham, Switzerland, pp. 69–82. DOI:10.1007/978-3-319-44108-5_6

Richins, H. and Hull, J. (eds) (2016) Mountain Tourism: Experiences, Communities, Environments and Sustainable Futures. CAB International, Wallingford, UK.

Rupf, R., Wyttenbach, M., Köchli, D., Hediger, M., Lauber, S. et al. (2011) Assessing the spatio-temporal pattern of winter sports activities to minimize disturbance in capercaillie habitats. eco.mont 3(2), 23–32. DOI:10.1553/eco.mont-3-2s23

Sejm of the Republic of Poland (2004) Nature Conservation Act [Ustawa z dnia 16 kwietnia 2004 r. o ochronie przyrody], Pub. L. No. Dz.U. 2004 nr 92 poz. 880. Available at: http://prawo.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=WDU20040920880 (accessed 30 January 2019).

Sterl, P., Eder, R. and Arnberger, A. (2006) Exploring factors in influencing the attitude of on-site ski mountaineers towards the ski touring management measures of the Gesäuse National Park. eco.mont 2(1), 31–38. DOI:10.1553/eco.mont-2-1s31

Stethem, C., Jamieson, B., Schaerer, P., Liverman, D., Germain, D. et al. (2003) Snow avalanche hazard in Canada – a review. Natural Hazards 28(2–3), 487–515. DOI:10.1023/A:1022998512227

Taczanowska, K., Zięba, A., Brandenburg, C., Muhar, A., Preisel, H. et al. (2016) Visitor Monitoring in the Tatra National Park – a Pilot Study – Kasprowy Wierch [Monitorig ruchu turystycznego w Tatrzańskim Parku Narodowym – Studium pilotaźowe – Kasprowy Wierch 2014]. Research Report. Institute of Landscape Development, Recreation and Conservation Planning, University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences, Vienna, Austria.

Tatra National Park (TNP) (2017) Decree Nr 3/2017 of the Tatra National Park Director from 23.02.2017 on hiking, bicycling and skiing in the area of the Tatra National Park [Zarządzenie nr 3/2017 Dyrektora Tatrzańskiego Parku Narodowego z dnia 23 lutego 2017 roku w sprawie ruchu pieszego, rowerowego oraz uprawiania narciarstwa na terenie Tatrzańskiego Parku Narodowego]. Available at: http://tpn.pl/upload/filemanager/Danka/Zarzadzenie_3_2017_w_spr_ruchu_pieszego_rowerowego_itp.pdf (accessed 30 January 2019).

Tatra National Park (TNP) (2018) Tatra National Park. Available at: http://tpn.pl/poznaj (accessed 30 January 2019).

TOPR (2018a) Komunikat Lawinowy – Tatry Polskie. Available at: http://lawiny.topr.pl (accessed 30 January 2019).

TOPR (2018b) Sprawozdanie z działalności ratowniczej TOPR w Zorganizowanych Terenach Narciarskich. Unpublished report. Zakopane, Poland.

TOPR (2018c) Zestawienie statystyczne działań TOPR w ramach Ratownictwa Górskiego. Unpublished report. Zakopane, Poland.

Yarmoloy, C., Bayer, M. and Geist, V. (1988) Behavior responses and reproduction of mule deer (Odocoileus hemionus), does following experimental harassment with an all-terrain vehicle. Canadian Field Naturalist 102(3), 425–429.

Ziemilski, A. and Marchlewski, A. (1964) Zwiad socjologiczny w Tatrach. Badania nad ruchem turystycznym w rejonie Hali Gąsienicowej. Wierchy 33, 51–76.

Zwijacz-Kozica, T. (2007) Tokowiska cietrzewi w centralnej części Tatrzańskiego Parku Narodowego i ich potencjalne zagrożenie ze strony narciarstwa. Presented at the I Międzynarodowa Konferencja Ochrona Kuraków Leśnych, Janow Lubelski, Poland, pp. 145–152.