Fig. 22.1. Value chain in alpine tourism. (Own figure based on Bieger and Beritelli, 2013.)

1Tourism Academy, College of Higher Education Lucerne, Lucerne, Switzerland; 2Tourism consulting company haller-tournet, Felsberg, Switzerland; 3Swiss Institute for Entrepreneurship (SIFE), University of Applied Sciences HTW, Chur, Switzerland; 4COTRI China Outbound Tourism Research Institute, Hamburg, Germany and Beijing, China; 5Institute of Natural Resource Science, Zurich University of Applied Sciences, Wädenswil, Switzerland

*E-mail: barbara.haller@haller-tournet.ch

Tourism is a globally fast-growing industry and in particular new guests from Asia boost the annual growth rates up to 6% (UNWTO, 2018). This growth is being pushed by the Chinese market, the largest international outgoing market in terms of frequencies and expenses (WTO, 2017). Some questions arise in this context: Who benefits from this growth? How can destinations and service providers realize added value from these new guests? How do Chinese guests perceive landscapes? Are they interested in winter experiences?

The average increase of Chinese guests to Switzerland from 2005 to 2016 was 17% annually (Bundesamt für Statistik, 2016). Arlt (2017) predicts a future annual growth rate of Chinese guests to Europe of 6–8%. Switzerland is considered to be a dream destination for the Chinese (Hu et al., 2014), known as a safe country in the middle of Europe, home to snowy mountains and photogenic landscapes and towns, expensive and ideally suited to shopping for luxury items such as watches.

With only 2% market share, the tourist destinations of Grisons, a mountainous province in the east of Switzerland, whose regional economy is overall based 30% on tourism and whose valleys are reliant on tourism for up to 70% of the economy (Bühler and Minsch, 2004), hardly participates in the Chinese tourism market (Plaz and Bösch, 2015). However, in the past few years Chinese guests’ overnight stays have been rising steadily, in 2016 by 28%.

Grisons’ small market share is, among other reasons, a consequence of Chinese trip planning as large groups bypass the region normally. Therefore, the destination’s focus on small groups and individual travellers could be a good strategy with future potential bearing in mind the current discussion about over-tourism in some destinations. Furthermore, ‘insight travelling’, visiting one or two countries in 10 days and not up to four countries in 5–7 days, is considered as the most important tourist trend in China (Arlt, 2018).

However, the market is only interesting if it brings not just increased numbers, but also income and added value to the regional economy. In many places Chinese first-time travellers are considered less lucrative due to their low spending on tourism services (Keating and Kriz, 2008).

This article presents two studies: ‘China Inbound Service’ a project to investigate the needs in alpine destinations to host Chinese guests and a pilot study regarding nature perception of tourism students in Shanghai.

In order to achieve the goal of adding value, it is crucial to develop local competencies regarding the Chinese market. In particular, knowledge of the customers’ expectations and motives (Laesser et al., 2013), the ability to develop and adapt new and existing tourism products (Keating and Kriz, 2008), and the sensitization and training of the service providers and their employees focusing on the new customer group.

Due to these requirements, the project ‘China Inbound Service’ focuses on the following objectives:

1. Analysis of current and potential customers, especially their expectations and behaviour.

2. Organizational development in the destinations and in market cultivation.

3. Development of customized products and services for Chinese guests in alpine destinations.

4. Awareness raising and education of the service providers and their employees to the new customer group.

5. Transfer of the project’s results to other long-distance markets, such as India or the Gulf States. Furthermore, to distribute them to other destinations in Grisons.

Bieger and Beritelli (2013) adapted the idea of Porter’s value chain for the specific situation of touristic destinations and created their ‘touristic value chain’. Porter introduced the value chain concept back in 1985 (Porter, 1985). This describes the necessary activities for the production of goods and services within a manufacturing enterprise as a sequence of processes, starting from the primary material and ending with the finished product. As the processes occur, value is created while resources are consumed (Porter, 1985). In later years, this concept was also adapted by him and other authors to the creation of services (e.g. Benkenstein et al., 2007). In the planning of tourism offerings of a region/destination, such a value chain can be used as a tool to ensure the compatibility of individual travel modules and to mediate between the service providers (hotels, transport companies, etc.) and other participating organizations (Koch, 2006).

Figure 22.1 shows the service chain of a destination in alpine tourism and is adapted from Bieger and Beritelli (2013). The upper part depicts the supporting processes with personnel, management, control and marketing functions. The lower part illustrates the processes of the customer experience cycle, from information and booking to the actual journey and the after-sales services.

In order to gain specific insights into the Chinese guests as well as product and destination development, three different investigations were carried out; one expert, guest and focus group survey each. Initially, ten expert interviews were conducted with European and Chinese experts from national marketing, tour operating, customer perspective, science, etc. On the one hand, these discussions served as a basis for the guest survey, on the other hand, a first glimpse into the travel motivation of the largely unknown group of FIT (foreign independent tourist) travellers from China was offered. In the winter season 2015/16, Chinese-speaking guests from the People’s Republic of China, Hong Kong and Taiwan were questioned in the participating destinations by survey. At the same time, research partners from China interviewed the focus group of potential guests in Beijing. The focus of the ‘on-site interviews’ was on the effective behaviour of the guests. In Beijing, the expectations of potential customers were in the foreground. The tourism monitor Switzerland 2013 TMS (Schweiz Tourismus, 2012) as well as a Scandinavian survey of Chinese guests (Wonderful Copenhagen, 2013) form the basis for the visitor survey in the alpine destinations.

In order to reach only Chinese overnight guests, the questionnaires in Chinese and English were laid out in the hotels of the destinations and the guests were made aware of them. With 106 useable questionnaires, the return was satisfactory. Although about one-third of respondents said they had good English skills, almost all questionnaires were completed in Chinese and then translated into English. The focus group survey was conducted by Chinese research colleagues in Beijing with eight people, four men and four women, aged between 26 and 64 years. The participants were recruited via Weibo and WeChat. Requirements for participation were an elevated economic background and travel experience in Europe (six of the respondents had already been to Switzerland). The first part of the focus group survey addressed the expectations of potential guests. In the second part of the interview, the focus group commented on summer and winter activities in the Alps and assessed a concrete multi-day offer. The entire survey was recorded and transcribed and finally translated into English for further analysis.

The results from the above three surveys are summarized below. The results of the customer survey show the status quo in retrospect; from expert and focus group surveys, future-oriented findings are then derived.

The return rate of the surveys was dominated by two hotels, one from each destination. Due to this dominance, the sample cannot be considered generally representative of FIT guests in alpine destinations.

The results of our survey give a good insight into the needs and behaviour of Chinese guests in alpine destinations in Switzerland, which are focused on one matter, e.g. skiing. Our typical questioned Chinese guest is well educated (80% hold a university degree), belongs to the financial upper class and comes from Beijing, Shanghai, the coastal areas or lives as an expatriate in Europe. The English language skills of most of the guests surveyed (besides those from Hong Kong) are rated as relatively low. Most of the guests travelled on individual travel plans (FIT travellers) with family and/or friends. Online information was obtained mainly through TripAdvisor, WeChat, Weibo and Baidu, and to some extent Google. Forty per cent of the bookings of (partial) offers were made online.

Only one-third of the guests were visiting Europe for the first time, nearly 50% were visiting Europe for the second to fifth time and almost 20% had already visited the continent more than five times. For two-thirds of the guests it was the first trip to Switzerland, the specific destination was unknown to almost all respondents.

In order to gain better insights into the needs and behaviour of Chinese guests, we asked for their perceived importance of and satisfaction levels with various criteria (see Fig. 22.2), on a Likert scale of 1–5 (1 = not important/not satisfied, 5 = very important/very satisfied), analogous to the TMS 2013.

According to the assessed importance attributed by the Chinese guests, safety and cleanliness are paramount, followed by accessibility by public transport as well as the competence and friendliness of the employees in the destinations. Importance and satisfaction correspond for most of the criteria. Sometimes, satisfaction is even higher rated than importance. Only for ‘signposting’, is importance much higher rated than satisfaction. In general, it can be stated that the criteria that were important to the Chinese guests also had the highest satisfaction levels. The highest rating of ‘safety and security’ applies to physical security, security in activities, e.g. skiing, as well as to reliability in offers and prices. According to the customer survey, guests were the least satisfied with shop opening hours, food offerings and the provision of information in Chinese – specifically, apps, tourism information, signs and maps, the destination website and Chinese-speaking staff. In all these cases, the importance was rated much higher, in some cases the corresponding mean value is >0.5 points above the satisfaction value.

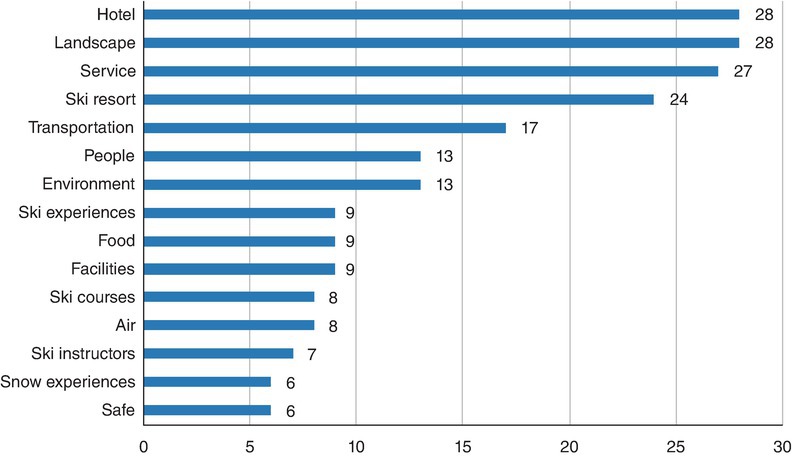

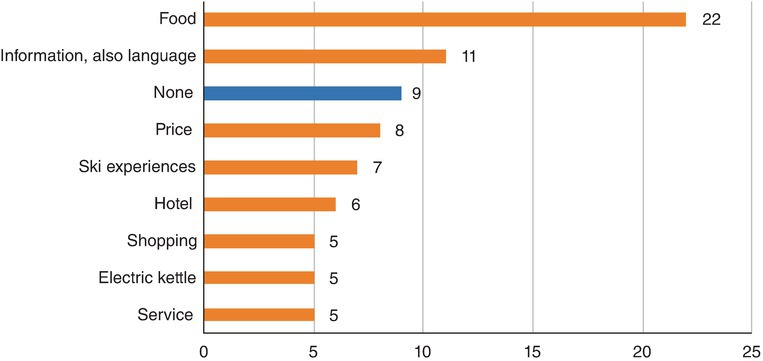

The results above are reflected in the open questions about best (positive, see Fig. 22.3) and worst (negative, see Fig. 22.4) experiences during the stay: the best responses were for hotel, landscape, service in general and the ski resort (28 to 24 times), followed by transportation (17), people and environment (both 13). Food was negatively mentioned (22 times), from the relatively low variability, the unfamiliar taste, the lack of Asian food, to the lack of information about the food. The second major criticism was lack of information in Chinese or at least in English (about food, accommodation, excursions, etc.).

Fig. 22.3. Positive customer experiences (number of positive mentions to an open question, max. three answers possible, n = 94).

Fig. 22.4. Negative customer experiences (number of negative mentions to an open question, max. three answers possible, n = 71).

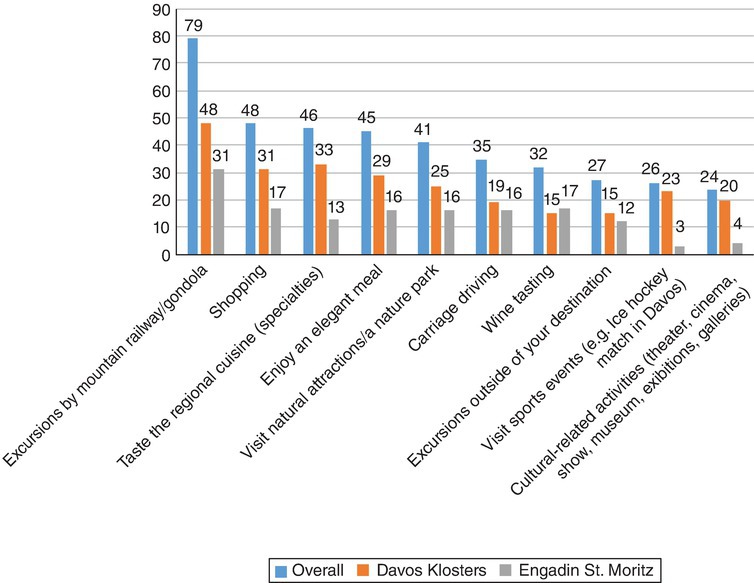

Fig. 22.5. Top ten non-sporting activities (number of mentions, multiple answers possible, n = 101).

The pure and clean appearance of the landscape in Switzerland was mentioned as very different from Chinese cities, as it is ‘natural’ and little influenced by humankind (see also Section 22.3 in this chapter).

To overcome the criticism in the areas of ‘food’ and ‘information’, simple adaptations could be made. For instance, the possibility of sharing food or taking souvenirs could be actively supported by the hosts, and hence the recommendations could be increased. By offering the information materials in Chinese, the destinations could express special respect for the guests from this market. For smaller service providers, the offer of English information (e.g. menus) would be an aid. These findings are largely consistent with the studies of Li et al. (2011), ETC and WTO (2012) or McKinsey & Company (2016). Li regards the food and service quality as well as an understanding of Chinese culture as the basis for good tourism services. In the ETC and WTO (2012) study, high prices, lack of Chinese information and food receive the worst ratings.

According to the survey, the activities most frequently mentioned by the Chinese winter guests were trips on mountain railways (84%), the enjoyment of local food (46%) as well visits to natural attractions and nature parks (41%).

Owing to the special ski offers from the hotels, from a sporting point of view, skiing (86%), short winter hikes (57%) and other winter activities (33%) such as snowshoeing or sledging were very popular. Snow sports lessons were popular in the destination with a Chinese-speaking ski instructor at 27%, versus 3% without a corresponding offer. Similarly, swimming was mentioned by 55% due to the indoor pool at the hotel.

As expected, shopping was important: interestingly, shopping activities in alpine destinations focused on chocolate (72%), ski and winter sports equipment (68%), souvenirs (62%) and local design (57%). Watches (34%) and luxury items (25%) were not much in demand.

The expert and focus group survey on product and organizational development brought interesting results: in order to meet the need for security and lack of time, modular packages should be available. For guests from China, travelling always includes a ‘learning component’ – explanations of landscapes, customs and food are therefore asked for in the offers and ‘study visits’ would also be an attractive offer for FIT guests. Winter sports are experiencing a major boom, especially because of the 2022 Winter Olympics in (North) China.

Generally, it can be stated that while there are numerous studies looking at Chinese outbound tourism and consumer behaviour (Tsang and Hsu, 2011), theory-based implementation concepts in the alpine region are almost completely lacking in product development and service adaptation (Andreu et al., 2013). In order to fill this gap, the participating destinations were given a concept to coordinate their engagement in the Chinese market. The value chain in Fig. 22.6 illustrates the interaction and responsibilities of all parties involved, thus simplifying the coordination and increasing the clarity of activities.

Fig. 22.6. Value chain of the ‘China Inbound Service’ project. (Based on Bieger and Beritelli, 2013.)

To meet the needs of the new group of guests and the needs of the destinations, a land tour operator (LTO) was established. Based in Switzerland, the LTO has sales offices in China and there takes the role of a Chinese tour operator by offering tailor-made products. Due to the local knowledge and the direct contact with the Swiss service providers and destinations, the guests’ needs can be served optimally. Additionally, there is a Chinese-speaking concièrge (guest relations manager) in the destinations to support the service providers, the LTO as well as the Chinese guests.

In the upper part of the value chain, the so-called support processes, there is close cooperation between all participants: the LTO, the service providers and destinations as well as the research partners. Important activities include, for example, offer development, planning and bundling as well as employee training.

In addition to the organizational changes, the project results were used to launch further measures with regard to the Chinese market:

• A cross-destination database that lists services and tourism products adapted to the needs and expectations of Chinese FIT guests. The aim of this database is to facilitate the cross-destination collaboration.

• A criteria catalogue for service providers to review the suitability of their products for the Chinese market. This catalogue is based on studies such as Li et al. (2011), as well as on various ‘tool kits’ for service providers to serve Chinese guests (Tourism New Zealand, 2013; Tourism and Events Queensland, 2013; Edinburgh Tourism AG, 2016).

• Furthermore, workshops and individual counselling sessions were offered to the service providers to support them in product development.

It is planned to bundle the offers and products that are adapted to the Chinese market to use them for a common market presence. Therefore, based on the criteria catalogue, the requirements for the service providers who are interested in the collective sales activities as well as the destination organization will be defined. Due to the size and diversity of the Chinese outbound tourism market it is hardly possible for individual service providers and even destinations to develop the necessary market knowledge and an active sales network on their own. Finally, with the power of the common market cash outflow should be avoided.

It is widely known and also recognized in the project ‘China Inbound Service’, that Chinese guests expect partly different products and services to guests from Europe or North America. From the criticism of the guests regarding food, information and lack of understanding of their culture, the destinations took first initiatives. The Asian eating habits could be catered for in hotel kitchens, restaurants or by third-party providers (catering) at low cost and with little extra effort. In addition, design and translation services were provided on-site and online to meet the need for information, be it for menus or offer descriptions. Due to Switzerland’s restrictive immigration policy towards third countries, a higher hurdle is the requirement for Chinese-speaking employees at the destinations. A first step is a Chinese-speaking ‘guest relations manager’ (concièrge) at the destinations. It can be assumed with an increasing number of Chinese guests, there will be a demand for Chinese-speaking employees from the service providers themselves.

Adapting tourism services to guest expectations is crucial (Chang et al., 2010; Andreu et al., 2013; Laesser et al., 2013), as linguistic barriers in particular could discourage potential FIT guests from travelling to alpine destinations. Despite the above criticism, Fig. 22.2 shows that the criteria of safety, cleanliness, accessibility, etc., which are considered very important, meet the expectations of the guests. The existing general and tourist infrastructure of Switzerland forms a promising basis for the development of incoming tourism from China. Investing in the Chinese market could become lucrative for alpine regions: in addition to the large potential due to the market volume, Chinese guests also travel anti-cyclically to the existing travel times. This could help to reduce the negative effects of seasonality in alpine tourism.

Nowadays a stay in the Alps is usually associated with nature experiences. Therefore, the interest of Chinese guests in winter holidays in the Alps depends, among other factors, on their perception of nature.

First, it should be stated that Chinese guests differ a lot in the way they travel, their travel expectations and motivation as well as in their perception of nature. When it comes to Chinese ethical positions in relation to nature, ancient traditions, cultural values, religious and philosophical beliefs – Taoism, Buddhism and Confucianism – each have profoundly impacted the way Chinese people view nature (Gao et al., 2018).

Within these philosophical beliefs, there is often not a unity regarding nature perception. On the one hand, there is the ‘Tian ren he yi’ [oneness of nature with humans or unity of humans and heaven] thinking; on the other, pragmatic utilitarianism appears to be of more relevance and importance to Chinese people in everyday life (Gao et al., 2018). Many scholars label the Chinese view as anthropocentrism (Bruun, 1995).

As the culture in mainland China is widely based on Confucian values, there are good reasons for investigating fengshui as a key element in the Chinese approach to nature (Bruun, 1995). From a European perspective it is important to understand that among Confucian values nature by itself is not perfect, but can be changed and harmonized by humans and their culture to improve fortunes (Han, 2006). Whereas in the West, nature is able to exist without human beings, in China they are considered to be as a never beginning or ending part of nature (Bruun, 1995). Traditionally in China there exist great concerns for nature, and how to bring it to bear positively on human fortune, whereas the distant, the unimportant, the invisible or even other people’s nature are not included in fengshui concerns. Chinese culture optimizes the use of natural powers, even to a degree where the ‘Qi’ – universal energy – is regarded as a limited resource subject to human competition (Bruun, 1995).

Feng Han (2006, p. 231) in his thesis ‘The Chinese view of nature: tourism in China’s scenic and historic interest areas’ supports the above-mentioned statements with propositions such as ‘nature is shaped by high culture’ or ‘nature is a place of cultivation’. At the same time, nature is seen as an ‘ideal place’ and a retreat, expressed by ‘nature is a symbol of great beauty and morals’, ‘nature is embedded with the meaning of ideal life’ or ‘nature is a place for retreat from worldly society’. However, statements such as ‘artistic re-built nature is more beautiful than original nature’ and ‘the eternal value of nature is for a harmonious and artistic human life’ show the different views of nature in China compared with the West in an exemplary way.

After the industrialization period, in Europe in the early 20th century and in the US in the 1970s, the protection of nature and cultural landscape gained in importance based on an alienation from nature in daily life (Bätzing, 2015). Forster and Rupf (2007) see the ‘longing for compensation of nature experiences’ as the starting point on the one hand, for nature conservation and the establishment of protected areas, and, on the other hand, for the demand for tourism and leisure activities in nature or in the wild. In Europe and America this consumer demand was the basis for the development of the outdoor industry with tourist offers including guiding, infrastructure and equipment.

Similarly in China, with the increase in population and urbanization since 1990, natural, historical and cultural landscapes and wilderness increased in acceptance and attractiveness and became a symbol of wealth and power for the privileged new elite urban class. Since the urbanization rate in mainland China rose from 28% in 1993 to 56% in 2017 (Hsu, 2016), the attractiveness of ‘Scenic and historic interest areas’ has increased as well, as they are expected to provide primarily ‘Outstanding natural beauty’ as mountains and lakes and ‘Excellent ecological qualities’ (Han, 2006, p.127).

In addition to pristine nature, cultural features, e.g. to be mentioned in history or poems, are very important tourism areas to attract visitors and to gain recognition. Therefore, newly discovered beautiful landscapes such as Jiuzhaigou or Wulingyuan, which are denigrated for their lack of culture, try to gain a cultural identity, for example, by naming all the peaks, valleys and streams.

Culture is always emphasized if managers want a site to be seen as high class (Han, 2006) and also for commercial reasons. In China, the average entrance fee to National Level Scenic and Historic Interest Areas or World Heritage Sites is nearly 1% of the average GDP per person, about ten times more than that of other countries. This reflects the three characteristics of being expensive, controlled and elitist. Gao (2013) expresses the important price–benefit ratio for landscape visiting slightly differently in her master’s thesis. She states that if touristic sights in the Alps consist mainly of nature and sport activities, they might not be attractive enough for Chinese visitors (Gao, 2013).

In the context of urbanization, population growth and landscape loss in China, Gao et al. (2018) address an interesting phenomenon related to tourism: people born before 1980 have a stronger connection to nature and are more aware of China’s landscape change than those born after 1980. People above the age of 40 years seem to be more concerned about the loss of nature and the pollution of the environment. Therefore, they are more interested in learning about natural phenomena, and are more likely to support nature protection in the Western sense, unlike the younger generation, who are mainly interested in management issues regarding natural areas.

One common feature of many nature tourism studies in China is that customers’ safety, accessibility and convenience are top priorities (Li et al., 2011; Zhang et al., 2013). In particular, if the security aspect is not satisfactory, nature attractions are not visited and products not booked.

The principle of ‘safety first’ from the customer’s point of view is also reflected in the results of the following study on the perception of nature and in the customer surveys of the ‘China Inbound Service’ project.

As alpine tourism products are based on nature to a large extent, it is crucial for service providers and destinations to know about the attitude towards nature of the (new) Chinese guests. On the one hand, this is based on traditional cultural values such as Confucianism; on the other hand it is related to the newest history and development of China. Due to urbanization and economic growth combined with environmental degradation, modern life in China’s cities – the target regions for outbound trips – is far from nature. Therefore, tourists from China are increasingly longing for nature experiences, but at the same time, they are often not used to it and therefore more anxious and worried about safety than tourists to the Alps so far.

To gain an insight into how young, tourism-related Chinese people rate different alpine landscapes in terms of their their attractiveness for tourism or leisure reasons, a survey among tourism students was conducted. In January 2018, 31 students from the Shanghai University of Engineering Science were asked in a short questionnaire to rate three pictures of the summer season and two pictures of the winter season according to the following questions:

1. Would you refer to the landscape as ‘nature’? Answers: yes/no

2. a) Would you like to spend time there as a tourist? Answers: yes/no

b) What are the reasons for your answer to Question 2a? (Open question).

The answers to the open question 2b were classified in the areas of ‘Safety’, ‘Landscape’, ‘Convenience’ and ‘Entertainment’ (see Table 22.1).

Whereas pictures A–D are significantly rated as nature (p < 0.02), for picture E the nature rating was not clear (p = 0.215). Regarding the question of whether participants were likely to spend leisure time in the shown landscape, pictures A and C were rated as significantly positive (p < 0.02), whereas acceptance of pictures B, D and E wasn’t significant for the reasons ‘too dangerous’ or ‘too cultivated’.

For the students in Shanghai safety reasons were most important; if safety is in doubt, participants are not likely to spend leisure time in a specific landscape, even if the landscape was unique to them as in picture 4. Additionally, it should be mentioned that one person criticized nearly each picture for the lack of culture and several participants rated the shown landscapes as beautiful, appealing, etc. but boring.

In matters of winter holidays, it can be stated that winter experiences such as playing in the snow, enjoying the landscape or a cable car ride were mentioned. Furthermore, skiing was mentioned by about half of the respondents. Skiing is a trend in China and the Olympic Winter Games 2022 in Beijing support it even more, which of course for alpine regions is a potential market.

The perception of nature by Chinese people and therefore Chinese tourists varies according to generation, living standard and cultural background. However, pristine nature can still be regarded as imperfect and therefore as not worth visiting. Therefore, lights, ornamentations or signposts add value to natural sites rather than disturb them. Furthermore, as soon as a landscape has a cultural or historical identity its attractiveness increases.

As described, the sample of this study consists of 35 tourism students. Therefore, it gives valuable insights into the landscape perception of potential Chinese guests, but it cannot be used to generalize, e.g. for experienced travellers.

Safety is crucial to all tourism products and landscapes and should be guaranteed and proved. Wilderness, steep and inaccessible terrain, and unknown environmental factors such as snow or wild animals are primarily scary for guests from China. Tourism products dealing with such aspects need to offer comprehensive information and guidelines, included guiding for reasonable prices. Likewise, aspects tourism infrastructure such as accommodation, restaurants and equipment shops or renting stations are expected.

Based on these insights it can be recognized that experiences such as a blue sky or stars, fresh air, drinking water from the tap, green meadows, walking barefoot or snowy mountains and powder snow are highlights for many Chinese guests, but for frequent tourists to the Alps are a matter of course. For Chinese guests the attractiveness of the products increases if they include fun, new learning experiences and can be shared on social media. It can be assumed that the more experienced those guests become, the closer their consumption patterns regarding alpine tourism products will be to those of other guests.

Although the alpine region has only been visited by Chinese guests to a limited extent until now, for example in Chamonix, Interlaken or Lucerne (Bundesamt für Statistik, 2016), the expert and focus group survey as well as different studies, such as a study by the company Kairos Future for the European Commission (European Commission, 2016), indicate a great potential for the alpine regions for second-time or multiple-visit travellers. These guests are increasingly interested in nature as well as in sporting activities, offerings that are among the strengths of the alpine region. In addition, the interest in winter sports in China is growing on the one hand because of the economic and social development (Wu and Wei, 2015), and on the other because of the upcoming Olympic Winter Games in Beijing in 2022. The desire of Chinese guests to experience the winter and corresponding winter sports in their place of origin in the Alps offers great potential. Even more so, when products are adapted to the cultural-based expectations of the Chinese guests regarding safety, convenience and entertainment. Moreover, especially for winter sport offers, fun and experience should dominate.

To exploit the potential of the Chinese tourism market in the alpine region, it is important to be aware of the fast-changing travel behaviour and differentiate among consumer groups. Especially regarding the Beijing 2022 Olympic Games, the demand for winter sport activities will rise. At the same time, it is important to gain a foothold by bundling marketing resources in the huge Chinese market.

In conclusion it should be pointed out that the growing Chinese market in general and the FIT market in particular continue to pose new challenges to destinations and their service providers. Different concepts and tools, such as the value chain, criteria catalogue, offer databases, etc., can help to summarize and coordinate activities. Likewise, the experience from the Chinese market can be exploited for the development of further remote markets such as India, the Gulf States or Brazil.

In the field of nature and landscape perception combined with Chinese behaviour as winter tourists, hardly any research exists. In order to develop their awareness as potential target destinations, alpine regions in particular should be interested in this information.

We thank the two destinations Engadin St. Moritz and Davos Klosters for their cooperation and the Economic Development and Tourism Agency of Grison for enabling the project ‘China Inbound Service’. Furthermore, we thank the tourism faculty of Shanghai University of Engineering Science for their support of the nature perception survey.

Andreu, R., Claver, E. and Quer, D. (2013) Chinese outbound tourism: new challenges for European tourism. Enlightening Tourism 3(1), 44–58.

Arlt, W. (2017) COTRI Market Report. COTRI: China Outbound Tourism Research Institute, Hamburg/Beijing, Germany/China.

Arlt, W. (2018) COTRI Market Report. COTRI: China Outbound Tourism Research Institute, Hamburg/Beijing, Germany/China.

Bätzing, W. (2015) Die Alpen: Geschichte und Zukunft einer europäischen Kulturlandschaft. CH Beck Verlag, Munich, Germany.

Bieger, T. and Beritelli, P. (eds) Management von Destinationen. Oldenbourg Verlag, Munich, Germany.

Benkenstein, M., Steiner, S. and Spiegel, T. (2007) Die Wertkette in Dienstleistungsunternehmen. In: Bieger, T. and Beritelli, P. (eds) Management von Destinationen. Oldenbourg Verlag, Munich, Germany, pp. 51–70.

Bruun, O. (1995) Fengshui and the Chinese perception of nature. In: Bruun, O. (ed.) Asian Perceptions of Nature: A Critical Approach. Curzon Press, London, pp. 173–188.

Bühler, D. and Minsch, R. (2004) Der Tourismus im Kanton Graubünden. Wertschöpfungsstudie. HTW Chur, Chur, Switzerland.

Bundesamt für Statistik (BfS) (2016) Beherbergungsstatistik HESTA. BfS, Neuenburg, Switzerland.

Chang, R.C., Kivela, J. and Mak, A.H. (2010) Food preferences of Chinese tourists. Annals of Tourism Research 37(4), 989–1011.

Edinburgh Tourism AG (2016) Edinburgh China-ready business opportunities guide. Available at: https://www.etag.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/ETAG-China-Ready-Business-Opportunity-Guide.pdf (accessed 31 January 2019).

ETC and WTO (2012) Understanding Chinese outbound tourism – what the Chinese Blogosphere is saying about Europe. UNWTO, Madrid, Spain.

European Commission (2016) Tourism flows from China to the European Union – current state and future developments. European Commission, Brussels, Belgium.

Forster, S. and Rupf, R. (2007) Parkkonzepte – Gratwanderung zwischen Naturschutz und Tourismus, Newsletter – Zernezer Tage. Schweizerischer Nationalpark, Zernez, Switzerland.

Gao, J., Zhang, C. and Huang, Z. (Joy) (2018) Chinese tourists’ views of nature and natural landscape interpretation: a generational perspective. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 26(4), 668–684. DOI:10.1080/09669582.2017.1377722

Gao, L. (2013) Mainland Chinese tourists and the Swiss alps an ethnographic exploration. Master’s Thesis, HTW Chur, University of Applied Science, Chur, Switzerland.

Han, F. (2006) The Chinese view of nature: tourism in China’s scenic and historic interest areas. PhD Thesis, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, Australia.

Hsu, S. (2016) China’s urbanization plans need to move faster in 2017. Available at: https://www.forbes.com/sites/sarahsu/2016/12/28/chinas-urbanization-plans-need-to-move-faster-in-2017/#4e90a19b74db (accessed 31 January 2019).

Hu, T., Marchiori, E., Kalbaska, N. and Cantoni, L. (2014) Online representation of Switzerland as a tourism destination: an exploratory research on a Chinese microblogging platform. Studies in Communication Sciences 14(2), 136–143.

Keating, B. and Kriz, A. (2008) Outbound tourism from China: literature review and research agenda. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management 15(1), 32–41.

Koch, W. (2006) Zur Wertschöpfungstiefe von Unternehmen: Die strategische Logik der Integration. Deutscher Universitäts-Verlag, Wiesbaden, Germany.

Laesser, C., Bazzi, D. and Riegler, B. (2013) Tourismus 2020 – Nutzbarmachung von internationalen Tourismuspotentialen durch den Bündner Tourismus: Entwicklungen, Potentiale, Handlungsempfehlungen. Universität St. Gallen – Institut für Systematisches Management und Public Governance, St. Gallen, Switzerland.

Li, X.R., Lai, C., Harrill, R., Kline, S. and Wang, L. (2011) When east meets west: an exploratory study on Chinese outbound tourists’ travel expectations. Tourism Management 32(4), 741–749.

McKinsey & Company (2016) What’s driving the Chinese consumer. Podcast from April 2016. Available at: https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/china/whats-driving-the-chinese-consumer (accessed 31 January 2019).

Plaz, P. and Bösch, I. (2015) Sommergeschäft durch Touringgäste aus Asien beleben. Vertiefungsbericht(V2)im Rahmen des Projekts ‘Strategien für Bündner Tourismusorte’. Wirtschaftsforum Graubünden, Chur, Switzerland.

Porter, M.E. (1985) Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance. Free Press, New York.

Schweiz Tourismus (2012) Tourismusmonitor Schweiz 2013. Available at: https://www.stnet.ch/de/dienstleistungen/tourismus-monitor-schweiz.html (accessed 8 February 2019).

Tourism and Events Queensland (2013) Meeting the expectations of your Chinese visitors and making them feel welcome. Available at: https://cdn-teq.queensland.com/~/media/15c4dcb13eb643f0b1eb0931a9cb3eae.ashx?la=en-au&vs=1&d=20140515T115458 (accessed 1 April 2017).

Tourism New Zealand (2013) China toolkit. Available at: www.chinatoolkit.co.nz (accessed 1 April 2017).

Tsang, N. and Hsu, C. (2011) Thirty years of research on tourism and hospitality management in China: a review and analysis of journal publications. International Journal of Hospitality Management 30(4), 886–896.

UNWTO (2018) 2017 international tourism results: the highest in seven years. Press release from 15 January 2018. Available at: http://media.unwto.org/press-release/2018-01-15/2017-international-tourism-results-highest-seven-years (accessed 31 January 2019).

Wonderful Copenhagen (2013) Survey of Chinese visitors to Scandinavia. Available at: www.visitcopenhagen.com/sites/default/files/asp/visitcopenhagen/Corporate/PDF-filer/Analyser/Chinavia/chinavia_-_survey_of_chinese_visitors_to_scandinavia_-_final.pdf (accessed 15 March 2015).

WTO (2017) Penetrating the Chinese outbound tourism market – successful practices and solutions. UNWTO, Madrid, Spain.

Wu, B. and Wei, Q. (2015) China ski industry white book. Available at: www.fierabolzano.it/alpitecchina/mod_moduli_files/2015%20China%20Ski%20Industry%20White%20Book%20(20160505).pdf (accessed 31 January 2019).

Zhang, H., Chen, B., Sun, Z. and Bao, Z. (2013) Landscape perception and recreation needs in urban green space in Fuyang, Hangzhou, China. Urban Forestry and Urban Greening 12(1), 44–52.