Fig. 25.1. The 5200-year-old ‘Kalvträsk ski’ exhibited at Västerbottens Museum (© Moralist, 2017; licensed under CC-BY-SA-3.0.)

25 Development of Downhill Skiing Tourism in Sweden: Past, Present, and Future

Department of Geography, Umeå University, Umeå, Sweden

*E-mail: cenk.demiroglu@umu.se

Skiing is an activity that has evolved throughout millennia since the prehistoric and the ancient times. Its cradle is asserted as northern Eurasia, extending from Japan to Scandinavia (Edlund and Yttergren, 2016). Artefacts and petroglyphs discovered in Scandinavia and China date the history of skiing back to 10,000 years ago (Lund, 1996, 2007; Kulberg, 2007; Zhaojian and Bo, 2011). However, throughout these ages, skiing was mainly practised as a means for transport, hunting and battling, and it was only during the past two centuries that it became an object of sports, recreation and tourism. A first major step towards such change was taken in Scandinavia as the public started to get more involved with skiing as a means of sports and entertainment, and this trend stretched to the Alps and North America following an outmigration trend from Scandinavia, of especially miners, by the end of the 19th century.

During post-World War II, in line with the general boom in tourism, ski tourism grew exponentially due to rising leisure time and disposable income, improved transportation and the return of millions of soldiers trained for skiing for battling reasons. In some countries, downhill skiing tourism was seen as a critical opportunity to boost socio-economic development in the peripheral mountain regions, thus receiving strong governmental support. Starting from the 1980s onwards, the industry faced some maturity especially at the conventional destinations such as North America, the Alps and Japan. Today, ski recreation and tourism are a major industry with around 6000 ski areas that attract 400 million annual skier visits (Hudson, 2000; Hudson and Hudson, 2015; Vanat, 2018), yet still facing the challenge of market stagnation, now coupled with the ever more-felt impacts of climate change. Likewise, in Sweden, the downhill skiing industry is one of the leading outdoor recreation and tourism sectors, requiring a thorough assessment of its trends and challenges embedded in the past and anticipated for the future.

This chapter is organized into two main sections. First, it highlights the major milestones in the development of downhill skiing tourism in Sweden from a supply perspective. Then an outlook on the future of the industry is portrayed with a special focus on major issues such as the changing markets and climates.

As with the history of skiing in many other lands, the development of ski tourism in Sweden occurred in two distinct phases: the prehistoric and ancient times, and the period of industrialization – or, the ‘utility period’ and the ‘sports period’, as alternatively referred to by Edlund and Yttergren (2016).

Skiing in Sweden and its Nordic neighbours is at least as old as the region’s indigenous people, the Sámi. These semi-nomadic people have for many millennia lived in the northern parts of Norway, Sweden and Finland and north-west Russia, all of which are characterized as regions with long and snowy winters. The Sámi have utilized skiing as a natural mode of transport for travelling, hunting and herding reasons. Ski artefacts found in Kalvträsk (see Fig. 25.1) in northern Sweden have been dated back to 3200 BC of the Neolithic Age. Likewise, rock carvings of skiers discovered in Alta, Rødøy and Bøla in Norway have dates as old as 3000 to 6000 years (Kulberg, 2007). Later, skiing has been adopted also by other peoples of the region, as evident on a Viking Age rune stone, found in Böksta and dating back to the 11th century AD. On the bottom left of the stone (see Fig. 25.2) one can observe the depiction of an archer on skis, who is considered to symbolize Ullr – a god in the Norse mythology. The mythological eddas identify the troll-goddess Skaði also with skiing, implying that skiing had also become a status symbol, besides a utility tool, within the Scandinavian cultures by the turn of the millennium. This soon was reflected into aristocracy with the royalty getting involved in skiing, which had then become an essential mode of battling and communications, and partly a competition sport, for many centuries in Sweden (Martinell, 1999; Edlund and Yttergren, 2016).

Fig. 25.1. The 5200-year-old ‘Kalvträsk ski’ exhibited at Västerbottens Museum (© Moralist, 2017; licensed under CC-BY-SA-3.0.)

Fig. 25.2. Ski-god ‘Ullr’ depicted on Böksta rune stone from the 11th century (bottom left). (© Berig, 2007; licensed under CC-BY-SA-3.0.)

Skiing had its global evolution into an object of mass sports, recreation and tourism during the 19th and 20th centuries. In the mid-19th century in the Telemark region of Norway, then part of a royal union with Sweden, a special type of ski binding was developed enabling more people to enjoy skiing with an increased ease of turns, brakes, jumps and ascends. Public competitions regularly took place, especially around the city of Christiania (Oslo), and skiing grew around the idrett philosophy that promotes health and training and soon became a symbol of national identity for the Norwegians, who were to declare their independence from the union in 1905 (Bø, 1992; Lund, 1996). Meanwhile in Sweden, similar competition grounds were already established at various venues in cities and towns such as Stockholm, Gävle, Sundsvall and Jokkmokk by the end of the 19th century (Martinell, 1999). However, it could be said that skiing became a popular recreational sport in the beginnings of the 20th century when the Swedish Tourist Federation (Svenska Turistföreningen) and the Outdoor Association (Friluftsfrämjandet) became more involved with the development of mountain areas and skiing. The Outdoor Association initially promoted skiing through the demonstrations of the King’s Guard (of the United Kingdoms of Sweden and Norway), comprising Norwegian officers trained in skiing. Demand for skiing grew rapidly, as the sport was introduced to schools through courses and competitions and many school ski trips started to be organized. Moreover, following Norway’s secession from Sweden, the rising patriotism among the Swedes, who had acknowledged the lead of Norway in nature-based tourism resources and development, is claimed to have triggered the domestic demand towards their own mountains (Martinell, 1999; Nilsson, 2003; Edlund and Yttergren, 2016).

While cross-country skiing had already grown into a popular sport by the 1920s, as evident in the Vasaloppet race that has attracted thousands of skiers each year since its inauguration in 1922, downhill skiing tourism started to take the lead during the winter seasons with the establishment of the first mountain resorts such as Åre, which was already a well-known tourist destination for its mountain climate during the non-winter seasons – a transformation pattern similarly observed for the Swiss Alps during the same periods. Following World War II, increasing disposable income and leisure time, with paid vacations already ensured by the Holiday Act in 1938, and the spreading of car ownership, in addition to the already well-established rail network into the mountains, triggered the involvement of urban populations, beyond the aristocracy and the elite, in addressing their recreational needs. Installation of ski lifts from the 1940s onwards eased uphill transportation for downhill skiing, making it a common sport for a larger mass of tourists, whom Nilsson (2003, p. 34) calls the ‘lift people’, who ‘represented a social group where collective style, inspired by the working class, was mixed with an individual elite style’. Following opening of the first ski lifts in Åre, Storlien and Björkliden, the number grew into 180 by 1965 to respond to the increasing demand of this emerging market (Nilsson 2001, 2003; Hall et al., 2008; Lundkvist and Gerremo, 2017).

Starting from the 1970s, the Swedish government started to become more involved in promoting the expansion and ‘resortification’ of downhill skiing tourism, especially since they acknowledged more the power of this type of tourism in fostering regional development at peripheral mountain regions (Hall et al., 2008), resembling what the French government had already implemented for its mountain regions through the ‘Snow Plan (Le plan Neige)’ since the 1960s. Potential recreational areas of top priority were identified by the Leisure Commission to be located in the mountainous regions of Dalarna, Jämtland, Västerbotten and Norbotten counties (Nilsson, 2003). The first concrete outcomes of this impetus were reflected in the increasing quantity and quality of lifts installed. Following the construction of Sweden’s first aerial lift, the Åre cable car, many more aerial chair- and gondola lifts were built throughout the Swedish mountains during the 1980s and the 1990s. The total number of lifts increased from 347 in 1974 to 684 in 1982 and further to 906 in 1986, reaching a peak of 1050 in 1992, and thereafter entering a decline trend down to 800s by the turn of the century (Lundkvist and Gerremo, 2017). Nonetheless, the share of the Swedish population that had made a visit to the mountain regions once during the periods 1980–1984 compared to 1995–2000 rose from 73% to 84%. A major increase occurred for Dalarna (22% to 34%) while the other popular county, Jämtland, had a small increase from 30% to 32% and the remaining two mountainous counties, Västerbotten and Norbotten, registered slight declines from 10% to 7% and 11% to 10%, respectively. Moreover, the major activity during those visits had become downhill skiing, with 36%, compared with the 22% in 1984, of the visitors being engaged, followed by hiking, with its share remaining at 32%, cross-country/backcountry skiing, with a slight decrease from 25% to 24%, and snowmobiling, with a major increase from 9% to 16% (Fredman and Heberlein, 2003; see also Fredman and Chekalina, Chapter 16 in this book).

During the last decade of the 20th century, major labour, amenity and lifestyle migration to ski destinations in the Swedish mountains have also been observed. Ski tourism development has not only provided jobs for the locals but also attracted labour inflows of especially young populations; thus acting as a partial remedy to the rural decline faced within the region due to a shift away from the once labour-intensive primary sectors. However, then it could be argued that new nodes of socio-economic density have been created in the rural landscapes by ski resorts (Lundmark, 2005, 2006; Müller, 2006; Hall et al., 2008). Such pattern is also evident elsewhere in the world where ‘the ski industry is not only designed for the use of visiting urban populations, it also generates a process of urbanization amidst a peripheral rural context’, as noted by Lasanta et al. (2013, p. 104) in reference to the political ecological approach of Stoddart (2012) to skiing. In most extreme cases, one could even face the so-called ‘Aspen effect’, where the residents and incoming labour force cannot afford housing prices anymore and are displaced by the arrival of second home owners, and consequently peak-season traffic and off-season ghost towns are created (Clifford, 2002). In the case of Sweden, ski resorts have also become a major attraction for second home development. Lundmark and Marjavaara (2005) determined a significant positive relationship between proximity to ski lifts and the number of second homes by taking account of the 29,000 second homes located in mountain municipalities in 2001. Further studies show that ski and second home tourism development in the mountains brought mainly the urban rich (Müller, 2005), and a young labour force that is attracted not really by the job opportunities themselves but the lifestyle promised by the natural and built amenities of the mountain environment (Müller, 2006).

The global ski industry in the 21st century has been characterized by major challenges such as stagnation, hyper-competition and climate change. Many conventional ski destinations of the Alps, Nordic Europe, North America and Japan have been confronted with declining skier visits, while some rapidly emerging markets such as China have helped partly restore the global figure. Such decline is attributed to the changing demographics, such as the ageing populations, as well as increasing competition from other holiday and leisure activities (Vanat, 2018; National Ski Areas Association, 2018). Climate change, on the other hand, has its impacts felt ever more on ski resorts, resulting in seasonal shrinkages and variability and the consequent adaptive measures, such as snowmaking investments, by the industry and behavioural changes, such as spatial substitution, adopted by the consumers and even edging a competitive advantage for those relatively less exposed areas (Demiroglu et al., 2013; Steiger et al., 2019). A major survival response from the supply side has been a focus on expansion, extension and integration of ski resorts into mega attractions, diversified for a year-round offer and ensuring a stronger marketing and bargaining power. Such trends have been coupled with the rise of oligopolistic ski corporations, who have become the major players at the destinations, forming a destination organizational structure of what Flagestad and Hope (2001) have coined as the ‘corporate model’ that has been spreading from North America towards Europe since the late 1980s, following a need or opportunity for consolidation of the supply side over a mature market (Harbaugh, 1997; Hudson, 2000). Similarly, in Sweden, the financial crisis of the early 1990s had also set the stage for acquisitions over the ski resorts, and a few specialized industry giants had already evolved by the turn of the century (Nilsson, 2001, 2003; Nordin, 2007; Farsari, 2018).

Ski lift ticket revenues (see Fig. 25.3), along with many other relevant statistics (see Table 25.1), are a common performance indicator recorded by the Swedish Ski Areas Industry Association (SLAO, 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015, 2016, 2017, 2018). The revenues, in constant prices and net of the VAT, have had a jump start in the development phase of the 1980s with total sales increasing by 60% from 245 million SEK in the 1983–84 season to 390 million SEK in 1987–88, followed by a stagnation period of the late 1980s and early 1990s. After a leap in 1994, a stagnation and development cycle recurred until the season of 2007–08 where the sales hit the record amount of 1 billion SEK for the first time in the industry’s history.

SLAO reports include more detailed information about the past decade of the industry (see Table 25.1). Here, a striking growth is apparent for the past 5 years, after a period of undulation. Such a trend resembles that of the global ski industry, where a recovery is observed following a long stagnation trend (Vanat, 2018). Moreover, from 2004 onwards, lift ticket prices have started to increase at a rate above that of the Consumer Price Index, despite the reduction in the rate of VAT from 12% to 6% since the 2006–07 season (SLAO, 2010). This increase is partly attributed to the increasing investments in snowmaking and lifts (Falk and Hagsten, 2016). Although not based on the original index set by Falk and Hagsten (2016), it could be observed that the prices are growing even more, as the lift ticket price per skier visit hit an all-time high of 172 SEK in the 2017–18 season. Investments, on the other hand, were as high as 79% of the prior season’s lift ticket revenues in 2010–11. Breakdown of the investments in the past three seasons were 43%, 31% and 26% for lifts, snow management and accommodation, respectively, while 340 SEK million more investments are planned for the 2018–19 season (SLAO, 2016, 2017, 2018).

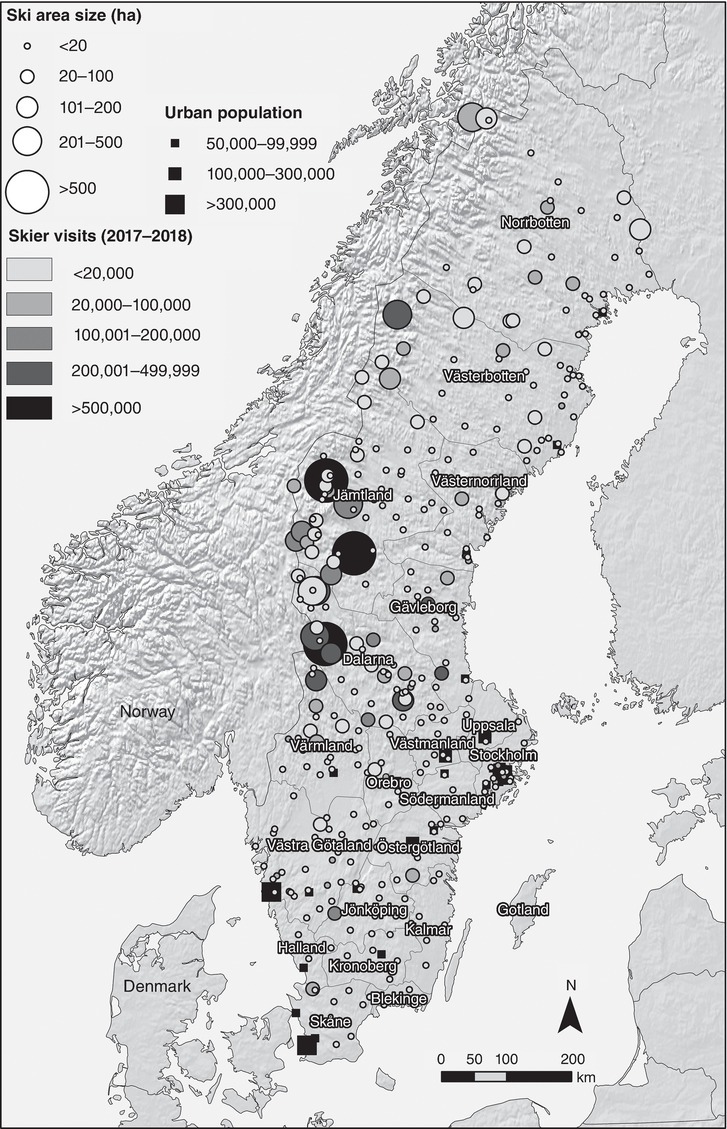

Fredman et al. (2012) determined the perceived value and cost of a downhill skiing trip in the Swedish mountains as 5290 SEK and 4710 SEK, respectively, yielding a net recreation value of 580 SEK per person during his/her stay in 2009 – compared with the 312 SEK surplus estimated for 1992 (Boonstra, 1993). On the other hand, ski visitation is not only limited to the tourists but also the local recreationists, spending that could be as low as one-seventh of the tourists’, as in the case of the US (Fredman et al., 2008, p. 46). When assessing the overall direct revenues from downhill skiing tourism and recreation in Sweden, the industry itself employs a rule of thumb that sets 1 SEK spent for a lift ticket to 10 SEK spent for the overall visits, including the expenditures on accommodation, food and beverages, equipment, etc. (SLAO, 2014, 2016). Taking account of the 2017–18 season, this approach yields a 17 billion SEK volume. Although such a figure may not constitute a significant share of the 5 trillion SEK GDP of Sweden, the spatial concentration of the industry reflects its importance in combating the socio-economic decline risk in rural and peripheral regions. A majority of the lift ticket revenues are generated in the two mountainous counties, Dalarna and Jämtland. Likewise, most of the skier visits are also paid to the ski areas within these counties (see Fig. 25.4). Also worthwhile noting, however, is the institutional accumulation of the revenue among very few players, with the top company leading the market by around 50% through its three large ski resorts and an urban ski area (see Table 25.1).

Fig. 25.4. Most visited (2017–18) and largest downhill skiing areas in Sweden. (From SLAO, 2018; courtesy of Jerker Moström, Statistics Sweden.)

A study by Statistics Sweden (Moström and Rosenblom, 2014) determined the number of downhill skiing areas in Sweden as 370. As of 2018, SLAO figures relate to 208 ski areas. The difference between these two figures is partly due to the differences between the counting methods of the two organizations, such that two nearby facilities could be considered as one single area by one of the parties and vice versa, but also mostly because not all ski areas, especially the micro-sized ones, are members of SLAO. Therefore, 370 could be taken as a reliable count, and the total number of lifts, together with the 840 in SLAO’s inventory, could be considered as around 1000, as also acknowledged by SLAO (2014, p. 18).

An attempt to map the distribution of all downhill skiing areas in Sweden in terms of their surface area (courtesy of Jerker Moström, Statistics Sweden) and the latest skier visits (SLAO, 2018) is displayed in Fig. 25.4. As a first step, the inventories of SLAO and Statistic Sweden are merged with each other, with the multiple entries created by the latter reduced down to the integrated ski resort level to conform to SLAO’s registry of skier visits. As a result, 336 ski resorts and areas with a total surface area of 9471 ha, including slopes, lifts, accommodations and all relevant facilities, were determined. The agglomeration of the industry in the central inlands is in line with the changed decision of the Leisure Commission on treating proximity to densely populated areas as a main factor in prioritization of the destinations to be developed in the 1970s (Nilsson, 2003). This also partly holds true with what the sports space theory suggests as ‘the natural resource base, rather than market access, will determine the locations where sport tourism takes place’ (Hinch and Higham, 2004, p. 90). Therefore, it could be expected that recreational tourism will find its development spots in the peripheries as these are usually the regions rich in nature-based resources. However, the fact that the mountainous and colder, yet very sparsely populated, northern inlands of Sweden have a relatively limited skiing offer does provide a counterargument for this view, and the many micro- and small-sized establishments observed within and around the urban localities further highlight the contribution of the market proximity factor. What really is applicable to the arguments by Hinch and Higham (2004), based on Christaller (1966) and Bourdeau et al. (2002), on the other hand, is a hierarchy of the peripheral ski destinations over the urban ski areas, where the ‘Big Three’, which have attracted 37% of skier visits and half of the lift ticket revenues in 2018, form the high-order product that attracts a national, and partly international, clientele, followed by competitors that mainly cater for regional and local demand.

Whether or not the current economic success trend, at least in terms of the lift ticket sales, of the Swedish downhill skiing industry can be maintained in the future is a matter of various human and physical factors. On the human side, general demographic and ski-specific behavioural changes of the consumers (see also Fredman and Chekalina, Chapter 16), as well as investment plans on the supply side, play major roles. On the physical side, climate change imposes a direct threat on the global tourism industry, thus many destinations and businesses need to cope with this phenomenon by assessing their vulnerabilities correctly and building resilience accordingly (Steiger et al., 2019).

As opposed to coastal mass tourism, ski tourism is mainly a domestic activity in many countries of the world (Vanat, 2018). While most European sunlust tourists need to travel to their Mediterranean neighbours or to exotic destinations such as South-east Asia and the Caribbean, ski tourists will usually find suitable places in their home countries or through convenient cross-border trips, the latter of which generate the main component of the so-called internationality of ski tourism. Moreover, generally in countries with a relative lack of snow and mountainous terrains, a snow sports culture is not well developed, hence no major international flows originating from these markets are recorded. An exception here is the British and the Dutch markets, where snow sports culture is historically strong but the natural base for developing ski tourism is limited for topographic and/or climatic reasons. Thus they, together with Germans and Russians, constitute an essential share of the incoming markets – mainly for the Alpine countries, who also have their own strong domestic bases. In Sweden, the most recent market studies (SLAO, 2011, 2016, 2018) show that the Swedes dominate the client base by 88%, 86%, 89% and 87% of the total skiers in 2009, 2011, 2016 and 2018, respectively, while the composition of the international interest comes mostly from the neighbouring Norwegian and Danish snow sports enthusiasts. Thus, it could be concluded that currently ski tourism in Sweden is mostly domestic with some additional interest from its immediate neighbours. Therefore, future changes in the economy and the demography of the country would have major implications.

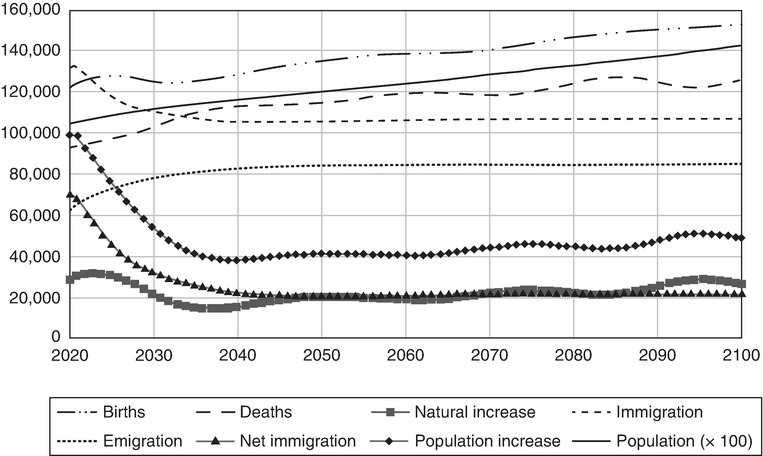

Future population changes for Sweden (see Fig. 25.5) are vital indicators of future trajectories in the domestic ski tourism market, as long as the current disposable income and leisure time levels are maintained or improved. As of 2011, 20% of the Swedish population, 1.9 million Swedes, were active visitors to Swedish ski areas and resorts. In 2018, 10% of the Swedish skiers were children aged between 0 and 7 years. This is considered as an advantage by the industry as the young skiers of today are expected to pass the torch to the next generation (SLAO, 2011, 2014, 2018). The demographic prognosis looks good with a constant increase in births, especially after 2030, and the consequent likelihood of newcomers to the ski market. Yet the competitiveness of skiing over other leisure, especially digital, activities, will remain in question, as has been the case among Generation X and Millennials in the US ski market (National Ski Areas Association, 2018), though a hybridization of mobile technologies with outdoor recreation in a way that mutually boosts the demand may also be on the rise (Svenska Camping and SLAO, 2013, p. 32). Likewise, any contribution from the future net positive immigration trend to the growth of the domestic ski market will be a matter of the origins of the immigrants and how they may be integrated into the market if they are unfamiliar with snow sports.

Fig. 25.5. Population projections for Sweden 2020–2100. (Data from Statistics Sweden, 2018.)

More than 5 billion SEK has been invested in Swedish ski tourism in the past decade (see Table 25.1). Despite a transfer of ski area proprietorship and management from associations, organizations and sports clubs to the private sector and then back to the non-profit organizations, via the municipalities and foundations, the influence of the corporate investors and operators is on the rise. This trend is often coupled with increased efforts for property development and sales, as evident through new and expanding resorts in the rural areas of Älvdalen, Umeå and Jokkmokk municipalities. While such projects may profit their investors and modify the regional socio-economic structure by boosting inflows of visitors, second home owners, labour and other entrepreneurs in the near future, they are also likely to fuel the debate on negative aspects of the corporate ski industry (Clifford, 2002), such as possible land use conflicts with the primary sector representatives.

In addition to the property investments, public–private initiatives on infrastructure and mega events are also worthwhile mentioning to get a better comprehension of the future of the Swedish ski industry. The two most striking developments in this respect are the Scandinavian Mountains Airport project and the Swedish Olympic Committee’s recent attempt on a bid for the 2026 Winter Olympic Games. The airport, planned to open prior to the 2019–20 season, has been developed through the efforts of an industry-leading company, together with state and municipal support, and, through its location at Dalarna’s Norwegian border, it is expected to ease accessibility of the area’s mega resorts for the Danish and the wider British, Dutch, German and Russian markets, and provide the region with an even higher order on the Swedish ski landscape (see Fig. 25.4). Yet it also remains a paradoxical development that shall foster air travel and greenhouse gas emissions, and thereby lead to shorter ski seasons (Andersson and Ahlgren, 2017). The 2026 Olympics, on the other hand, was planned to be hosted by Stockholm and Åre, following Sweden’s previous ambitious but never successful six bidding attempts from 1984 till 2002. While political and economic concerns remained over the costs and impacts of such a mega event, it could have eventually provided a major contribution to the internationalization of Swedish downhill skiing tourism, but the bid was lost to the Italian duo of Milan and Cortina d’Ampezzo.

The growth of downhill skiing tourism is an important input for regional development, especially in the sparsely populated rural and peripheral areas of Sweden. An early report by the Swedish government (Swedish Commission on Climate and Vulnerability, 2007) asserts that most ski areas, outside of the mountainous regions, may not be viable to operate, as their snow depths are projected to be <10 cm for more than half of the total number of days with snow cover by as early as the 2020s. The report stressed the importance of snowmaking for adaptation, yet also provided a reminder about the possible conflicts to come over the use of scarcer water resources of the future, especially in southern Sweden. Relocation to higher and north-facing altitudes was another adaptation suggestion, including even more radical ideas such as ‘a structural shift of winter tourism towards areas that are more assured of having snow in the northernmost parts of the country’ (p. 395). Moreover, a careful climate change impact assessment is also vital for the aforementioned Olympic bid in a future where the climatic suitability of even the once reliable previous hosts is under threat (Scott et al., 2019).

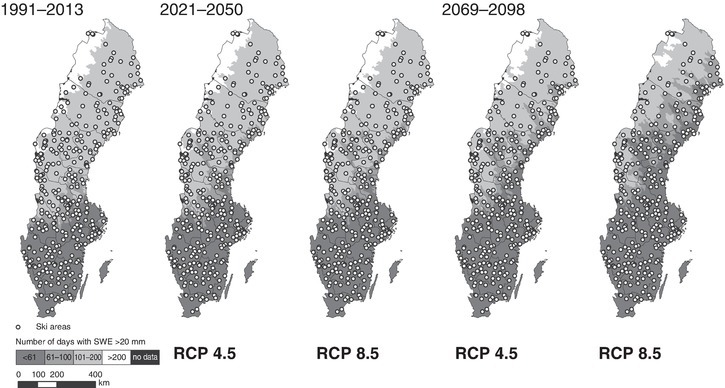

The only scientific study on the impacts of climate change on Swedish downhill skiing tourism predicts an economic loss for the end of the 21 century, which is larger than the total lift ticket revenues at the time of the study (Moen and Fredman, 2007). Since this study used the snowfall variable, instead of the more relevant snow depth variable, to explain natural snow reliability (Steiger et al., 2019), an alternative nationwide assessment (see Fig. 25.6) is made by the authors by mapping snow reliability indicators based on the snow cover projections available from the Swedish Meteorological and Hydrological Institute (SMHI, 2015).

Fig. 25.6. Natural snow reliability conditions in Sweden under climate change. (Data from SMHI, 2015.)

The results displayed in Fig. 25.6 are based on values per catchment area, rather than ultra-high resolution grids, therefore should not be taken for granted at the ski area/resort scale, but could be used as guidelines for larger regional development decisions. Here the SMHI projections on the ‘annual number of days with a minimum snow water equivalent (SWE) of 20 mm’ are treated as a natural snow reliability indicator, as 20 mm of SWE roughly represents a snow depth of 50 cm, taking a snow density of 0.4 g/cm3 as a reference for managed snow. This snow depth is considered as ‘good’ for downhill skiing (Witmer, 1986). The minimum number of days that meet this criterion are then further classified under various thresholds that indicate minimum viable season lengths for ski areas. Whereas the ‘100 days’ rule is commonly applied worldwide (Abegg et al., 2007), ‘60 days’ is also sometimes utilized especially in the case of warmer and urban or peri-urban ski areas that could take advantage of denser days in terms of visitation (König, 1998). A 200-day zone is additionally examined here to identify the (potential) regions with the longest natural ski seasons. The reference period is based on the 1991–2013 average and the future projections cover the 2021–2050 and the 2069–2098 periods under a relatively business-as-usual (RCP 8.5) and a rather optimistic (RCP 4.5) scenario (van Vuuren et al., 2011). Under both scenarios, major natural snow reliability issues emerge mainly around the coastal and southern parts by 2050. By the end of the century, almost all coastal ski areas, as well as those in the eastern parts of Dalarna and Jämtland, enter a non-reliability zone where the number of naturally skiable days is 60 or less. Here, the most reliable regions remain in the extreme northern inlands along the Norwegian border, and especially in and around Sarek and the Kebnekaise Massif.

While the above picture casts a partial shadow on the future of Swedish downhill skiing tourism, in reality, adaptation to climate change is already in effect, and many ski areas make use of snowmaking systems for both adaptation and competition reasons. The once natural snow-dependent lift ticket sales have started to become more liberated since the late 1980s (Falk and Lin, 2018). Already by 2009, 149 of the 227 SLAO member ski areas had snowmaking systems established (SLAO, 2009). During 2016–2018, a total of 375 million SEK was invested for snowmaking and snow management, e.g. grooming (SLAO, 2016, 2017, 2018). However, contemporary snowmaking systems are also sensitive to climate change as they require cold and dry weather conditions to operate. Above a certain wet bulb temperature, snow production is not possible, and at the limits, operational costs rise. Besides, they extensively compete for the water resources, as mentioned in the governmental report above (Swedish Commission on Climate and Vulnerability, 2007). Therefore, other adaptation measures (Scott and McBoyle, 2007) should also be on the agenda.

Diversification through the introduction of year-round and non-ski products is another common adaptation method observed among the Swedish ski resorts. Investment in mountain bike trails has become a trending differentiation method in the past decade, especially because it is one of the few alternative activities that can commercially justify expensive lift investments. However, the extent of such conversion/diversification is questionable as the biker market size may not be equivalent to that of the downhill skiers. Focusing on property development, on the other hand, does secure cash inflows at an earlier stage of the deteriorating snow reliability, yet transfers the risk of any value loss to the consumers, who will mostly be second home owners.

Perhaps, one of the most interesting adaptation efforts at the policy level then is the idea of relocation to the relatively advantageous north (Swedish Commission on Climate and Vulnerability, 2007; Brouder and Lundmark, 2013). The northern inlands display superior future snow conditions and could benefit from any spatial substitution behaviour arising among ski tourists not satisfied with their favourite ski resorts in the future. In fact, some established resorts of the area have already been declared as the ‘winners’ (Brändström, 2008), but in order for a real structural shift to happen, other national and international resorts would need to become more exposed to climate change. The two promising regions, Sarek and Kebnekaise, on the other hand, are not as blessed by winter sunlight, due to their Arctic latitudes, as they are by snow reliability, therefore their potential needs to be assessed within a more comprehensive attractiveness index. Moreover, these places are already well-established nature-based tourism destinations valued for their preserved amenities, and a land use change for the sake of ski resort development could bring in new conflicts.

While the ski areas of the mountainous regions, particularly in the north, may seem to be more resilient to climate change, it is apparent that a major problem will arise among the southern and the coastal ski areas (Brouder and Lundmark, 2011). This should not, however, be perceived as a total advantage for the resilient resorts, as most of these micro- and small-sized areas cater for local needs of the urban populations, and are usually the first points of contact and retention venues for the development and sustainability of the ski tourism market. Therefore, a problem in the most vulnerable areas could mean a problem for the most resilient, as the latter are partly dependent on the former’s performance in recruiting and maintaining a domestic skier base. Moreover, even outside these ski areas, a deterioration of the urban snow cover could reduce the so-called ‘backyard effect’ (Hamilton, 2007), resulting in an overall demotivation for ski trips. In the future, the industry as a whole, together with local and central governments, may need to contribute to the adaptive capacities of these vulnerable establishments, and even consider developing artificial ski areas at urban centres.

As opposed to the relatively inelastic position of ski tourism suppliers against climate change, the demand side could be highly elastic responding directly to the changing weather conditions. Moreover, some other rising trends within travel behaviour, such as climate friendliness (Demiroglu and Sahin, 2015) and hypermobility (Cohen and Gössling, 2015), could have their own effects on the Swedish downhill skiing industry. In response to the changing climate conditions, ski tourists may perform spatial or activity substitution. While the northern inlands could benefit from becoming an alternative to less snow reliable destinations, other regions in the country could lose much income due to such a spatial shift. Moreover, a study in Norway (Demiroglu et al., 2018) shows that less snow reliability at designated resorts could lead the consumers to freely exploit the snowiest regions on Telemark or alpine tour skis. While such equipment provides the riders with a similar joy to downhill skiing, it liberates them from the need for lifts for uphill transport, thus putting the industry at risk of losing a significant revenue item. The rising climate friendliness, on the other hand, calls for ‘staycations’ that promote low-carbon, local recreation, and this is also reflected in policies favouring carbon tax on flights yet putting remote ski resorts at risk (Boström, 2017). A contrasting current is then the ever-increasing hypermobility, which may have further consequences for destination loyalty and substitution.

Since the use of the first skis for utility reasons millennia ago, Sweden has come a long way to the point where skiing has become a significant object of contemporary mass tourism. Following first the involvement of the state for regional development goals in the 1970s and then the rise of the corporate players in response to the financial crisis in the 1990s, today Swedish downhill skiing tourism portrays a steady growth, in contrast to many of its conventional competitors in the international market. However, as in many parts of the global ski domain, downhill skiing demand is predominantly domestic and partly regional for Sweden, and the future success depends on the recruitment of new skiers from a growing population in a fierce competition against other increasingly popular recreation and leisure activities. In this respect, comprehensive assessments on the vulnerabilities of existing ski areas are also essential in order to maintain the levels of first contact at the local bases as well as to suggest new regions to accommodate the domestic and the likely substituting international demand.

This study was supported by the Swedish Research Council for Sustainable Development, FORMAS, as part of the project Mobilising the Rural: Post-productivism and the New Economy. We thank Jerker Moström from Statistics Sweden for sharing their inventory of the downhill skiing areas in Sweden.

Abegg, B., Agrawala, S., Crick, F. and de Montfalcon, A. (2007) Climate change impacts and adaptation in winter tourism. In: Agrawala, S. (ed.) Climate Change in the European Alps: Adapting Winter Tourism and Natural Hazards Management. OECD, Paris, pp. 25–60.

Andersson, J. and Ahlgren, J. (2017) En flygplats i Sälen är ett steg mot mindre snö och kortare vintrar. Available at: https://www.freeride.se/en-flygplats-salen-ar-ett-steg-mot-mindre-sno-och-kortare-vintrar/ (accessed 17 July 2019).

Berig (2007) Böksta runestone. Available at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:U_855,_B%C3%B6ksta.jpg (accessed 26 August 2018).

Bø, O. (1992) På ski gjennom historia. Norske samlaget, Oslo, Norway.

Boonstra, F. (1993) Valuation of Ski Recreation in Sweden: A Travel Cost Analysis. Umeå University, Umeå, Sweden.

Boström, A. (2017) Tomma skidbackar med dyrare flyg. Available at: https://www.svensktnaringsliv.se/regioner/vasterbotten/tomma-skidbackar-med-dyrare-flyg_687063.html (accessed 12 November 2018).

Bourdeau, P., Corneloup, J. and Mao, P. (2002) Adventure sports and tourism in the French mountains: dynamics of change and challenges for sustainable development. Current Issues in Tourism 5(1), 22–32. DOI:10.1080/13683500208667905

Brändström, M. (2008) Skidturism tjänar på nytt klimat. Available at: https://www.svt.se/nyheter/lokalt/vasterbotten/skidturism-tjanar-pa-nytt-klimat (accessed 26 August 2018).

Brouder, P. and Lundmark, L. (2011) Climate change in northern Sweden: intra-regional perceptions of vulnerability among winter-oriented tourism businesses. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 19(8), 919–933. DOI:10.1080/09669582.2011.573073

Brouder, P. and Lundmark, L. (2013) A (ski) trip into the future. In: Müller, D.K., Lundmark, L. and Lemelin, R.H. (eds) New Issues in Polar Tourism: Communities, Environments, Politics. Springer, Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 149–161.

Christaller, W. (1966) Central Places in Southern Germany (translated by C.W. Baskin). Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey.

Clifford, H. (2002) Downhill Slide: Why the Corporate Ski Industry is Bad for Skiing, Ski Towns, and the Environment. Sierra Club Books, San Francisco, California.

Cohen, S.A. and Gössling, S. (2015) A darker side of hypermobility. Environment and Planning A 47(8), 166–179. DOI:10.1177/0308518X15597124

Demiroglu, O.C. and Sahin, U. (2015) Ski Community Activism on the Mitigation of Climate Change. Istanbul Policy Center, Karakoy-Istanbul, Turkey.

Demiroglu, O.C., Dannevig, H. and Aall, C. (2013) The multidisciplinary literature of ski tourism and climate change. In: Kozak, M. and Kozak, N. (eds) Tourism Research: An Interdisciplinary Perspective. Cambridge Scholars Publishing, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, pp. 223–237.

Demiroglu, O.C., Dannevig, H. and Aall, C. (2018) Climate change acknowledgement and responses of summer (glacier) ski tourists in Norway. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism 18(4), 418–438. DOI:10.1080/15022250.2018.1522721

Edlund L.-E. and Yttergren, L. (2016) Skiing. In: Olsson, M.-O., Backman, F., Golubev, A., Norlin, B., Ohlsson, L. et al. (eds) Encyclopedia of the Barents Region: Vol. II, N-Y. Pax Forlag, Oslo, pp. 321–324.

Falk, M. and Hagsten, E. (2016) Importance of early snowfall for Swedish ski resorts: evidence based on monthly data. Tourism Management 53, 61–73. DOI:10.1016/j.tourman.2015.09.002

Falk, M. and Lin, X. (2018) The declining dependence of ski lift operators on natural snow conditions. Tourism Economics 24(6), 662–676. DOI:10.1177/1354816618768321

Farsari, I. (2018) A structural approach to social representations of destination collaboration in Idre, Sweden. Annals of Tourism Research 71(1), 1–12. DOI:10.1016/j.annals.2018.02.006

Flagestad, A. and Hope, C.A. (2001) Strategic success in winter sports destinations: a sustainable value creation perspective. Tourism Management 22(5), 445–461. DOI:10.1016/S0261-5177(01)00010-3

Fredman, P. and Heberlein, T. (2003) Changes in skiing and snowmobiling in Swedish mountains. Annals of Tourism Research 30(2), 485–488. DOI:10.1016/S0160-7383(02)00110-X

Fredman, P., Boman, M., Lundmark, L. and Mattsson, L. (2008) Friluftslivets ekonomiska värden: En översikt. Friluftsliv i förändring, Östersund, Sweden.

Fredman, P., Boman, M., Lundmark, L. and Mattsson, L. (2012) Economic values in the Swedish nature-based recreation sector – a synthesis. Tourism Economics 18(4), 903–910. DOI:10.5367/te.2012.0149

Hall, C.M., Müller, D.K. and Saarinen, J. (2008) Nordic Tourism: Issues and Cases. Channel View Publications, Bristol, UK.

Hamilton, L.C., Brown, B.C. and Keim, B. (2007) Ski areas, weather and climate: time series models for integrated research. International Journal of Climatology 27(15), 2113–2124. DOI:10.1002/joc.1502

Harbaugh, J.A. (1997) Ski industry consolidation or financing 90s style? Ski Area Management 36(6), 51–52.

Hinch, T.D. and Higham, J.E. (2004) Sport Tourism Development. Channel View Publications, Clevedon, UK.

Hudson, S. (2000) Snow Business: A Study of the International Ski Industry. Cengage Learning EMEA, Boston, Massachusetts.

Hudson, S. and Hudson, L. (2015) Winter Sport Tourism: Working in Winter Wonderlands. Goodfellow Publishers, Oxford, UK.

König, U. (1998) Tourism in a Warmer World: Implications of Climate Change due to Enhanced Greenhouse Effect for the Ski Industry in the Australian Alps. University of Zurich, Zürich, Switzerland.

Kulberg, Ø. (2007) From rock carvings to carving skis. Skiing Heritage 19(2), 34–37.

Lasanta, T., Beltran, O. and Vaccaro, I. (2013) Socioeconomic and territorial impact of the ski industry in the Spanish Pyrenees: mountain development and leisure induced urbanization. Pirineos: Journal of Mountain Ecology 168, 103–128. DOI:10.3989/Pirineos.2013.168006

Lund, M. (1996) A short history of alpine skiing. Skiing Heritage 8(1), 5–19.

Lund, M. (2007) Norway: how it all started. Skiing Heritage 19(3), 8–13.

Lundkvist, S. and Gerremo, H. (2017) Liftens historia. Available at: http://slao.se/fakta/liftens-historia/ (accessed 17 July 2019).

Lundmark, L. (2005) Economic restructuring into tourism: the case of the Swedish mountain range. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism 5(1), 23–45. DOI:10.1080/15022250510014273

Lundmark, L. (2006) Mobility, migration and seasonal tourism employment. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism 6(1), 54–69. DOI:10.1080/15022250600866282

Lundmark, L. and Marjavaara, R. (2005) Second home localizations in the Swedish mountain range. Tourism 53(1), 3–16.

Martinell, V. (1999) Skidsportens historia: längd 1800–1949. V. Martinell, Järna, Sweden.

Moen, J. and Fredman, P. (2007) Effects of climate change on alpine skiing in Sweden. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 15(4), 418–437. DOI:10.2167/jost624.0

Moralist (2017) Kalvträskskidan at the ski museum in Umeå. Available at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Skidmuseet_(02).jpg (accessed 26 August 2018).

Moström J. and Rosenblom, T. (2014) Skidbackarnas yta större än Täby. Available at: https://www.scb.se/sv_/Hitta-statistik/Artiklar/Skidbackarnas-yta-storre-an-Taby (accessed 26 August 2018).

Müller, D.K. (2005) Second home tourism in the Swedish mountain range. In: Hall, C.M. and Boyd, S. (eds) Nature-based Tourism in Peripheral Areas: Development or Disaster? Channel View Publications, Bristol, UK, pp. 133–148.

Müller, D.K. (2006) Amenity migration and tourism development in the Tärna mountains, Sweden. In: Moss, L. (ed.) The Amenity Migrants: Seeking and Sustaining Mountains and their Cultures. CAB International, Wallingford, UK, pp. 245–258.

National Ski Areas Association (2018) Model for growth. Available at: www.nsaa.org/growing-the-sport/model-for-growth (accessed 26 August 2018).

Nilsson, P.-A. (2001) Tourist destination development: the Åre Valley. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism 1(1), 54–67. DOI:10.1080/15022250127795

Nilsson, P.-A. (2003) Åre Tourism: the Åre Valley as a Resort during the 19th and 20th Centuries. Hammerdal Förlag, Hammerdal, Sweden.

Nordin, S. and Svensson, B. (2007) Innovative destination governance: the Swedish ski resort of Åre. The International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation 8(1), 53–66. DOI:10.5367/000000007780007416

Scott, D. and McBoyle, G. (2007) Climate change adaptation in the ski industry. Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies for Global Change 12, 1411–1431.

Scott, D., Steiger, R., Rutty, M. and Fang, Y. (2019) The changing geography of the Winter Olympic and Paralympic Games in a warmer world. Current Issues in Tourism 22(11), 1301–1311. DOI:10.1080/13683500.2018.1436161

SLAO (2009) Skiddata Sverige 2008–2009. Available at: http://slao.se/content/uploads/2016/11/SLAOstatistik_09.pdf (accessed 26 August 2018).

SLAO (2010) Skiddata Sverige 2009–2010. Available at: http://slao.se/content/uploads/2016/11/SLAOstatistik_10.pdf (accessed 26 August 2018).

SLAO (2011) Skiddata Sverige 2010–11. Available at: http://slao.se/content/uploads/2016/11/SLAOstatistik_10.pdf (accessed 26 August 2018).

SLAO (2012) Skiddata Sverige 2011–12. Available at: http://slao.se/content/uploads/2016/11/SLAO_skiddata_2011-12_webb.pdf (accessed 26 August 2018).

SLAO (2013) Skiddata Sverige 2012–2013. Available at: http://slao.se/content/uploads/2016/11/SLAO_skiddata_2012-13_webb.pdf (accessed 26 August 2018).

SLAO (2014) 2014 Snörapporten: Svenska Skidanläggningars Brancshrapport. Available at: http://slao.se/content/uploads/2016/10/Branschrapport_2014_webb_sidor.pdf (accessed 26 August 2018).

SLAO (2015) 2014–2015 Skiddata för Vintern: Svenska Skidanläggningars Brancshrapport. Available at: http://slao.se/content/uploads/2016/10/SLAOBranschrapport2015_pages.pdf (accessed 26 August 2018).

SLAO (2016) Branschrapport 2015/2016. Available at: http://slao.se/content/uploads/2016/10/160916-Branschrapport-slutlig-2016.pdf (accessed 26 August 2018).

SLAO (2017) Branschrapport 2016 2017. Available at: http://slao.se/content/uploads/2017/07/Branschrapport-2017-l%C3%A5guppl%C3%B6st.pdf (accessed 26 August 2018).

SLAO (2018) SLAO Branschrapport 2017 2018. Available at: http://slao.se/content/uploads/2018/07/SLAO_2018_Branschrapport_klar_juli.pdf (accessed 26 August 2018).

SMHI (2015) Nerladdningstjänst för SCID. Available at: https://data.smhi.se/met/scenariodata/rcp/scid (accessed 26 August 2018).

Statistics Sweden (2018) Population changes by observations and year. Available at: www.statistikdatabasen.scb.se/pxweb/en/ssd/START__BE__BE0401__BE0401A/BefPrognosOversiktN/table/tableViewLayout1/?rxid=86abd797-7854-4564-9150-c9b06ae3ab07 (accessed 26 August 2018).

Steiger, R., Scott, D., Abegg, B., Pons, M. and Aall, C. (2019) A critical review of climate change risk for ski tourism. Current Issues in Tourism 22(11), 1343–1379. DOI:10.1080/13683500.2017.1410110

Stoddart, M.C.J. (2012) Making Meaning out of Mountains: The Political Ecology of Skiing. UBC Press, Vancouver, Canada.

Svenska Camping and SLAO (2013) Framtidens utomhusupplevelser. Available at: http://utomhusupplevelser.se/static-content/rapport2013/framtidens-utomhusupplevelser-2013.pdf (accessed 26 August 2018).

Swedish Commission on Climate and Vulnerability (2007) Sweden facing climate change – threats and opportunities. Available at: https://www.government.se/contentassets/5f22ceb87f0d433898c918c2260e51aa/sweden-facing-climate-change-preface-and-chapter-1-to-3-sou-200760 (accessed 26 August 2018).

Van Vuuren, D.P., Edmonds, J., Kainuma, M., Riahi, K., Thomson, A. et al. (2011) The representative concentration pathways: an overview. Climatic Change 109, 5–31.

Vanat, L. (2018) 2018 International report on snow and mountain tourism: overview of the key industry figures for ski resorts.

Witmer, U. (1986) Geographica Bernensia: G25. Erfassung, Bearbeitung und Kartierung von Schneedaten in der Schweiz. University of Bern, Bern, Switzerland.

Zhaojian, D. and Bo, W. (2011) The Original Place of Skiing – Altay Prefecture of Xingjian, China. People’s Education Press, Beijing, China.