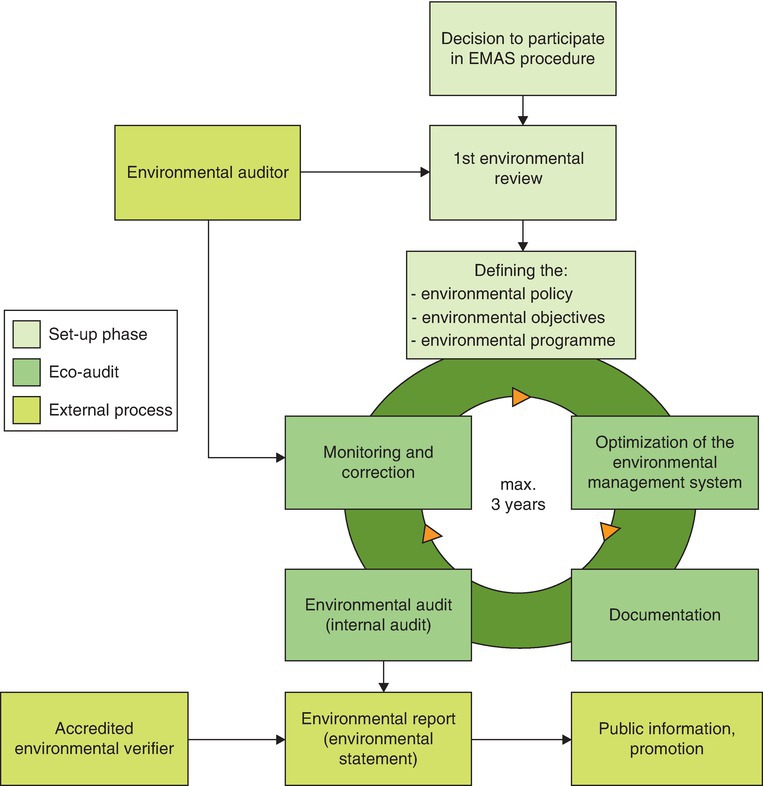

Fig. 29.1. Basic principles of environmental management according to EMAS. (Translated from Salak, 2008; original figure based on Pröbstl et al., 2003.)

29 How to Manage Ski Resorts in an Environmentally Friendly Way – Challenges and Lessons Learnt

Institute of Landscape Development, Recreation and Conservation Planning, University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences, Vienna, Austria

*E-mail: claudia.hoedl@boku.ac.at

Many winter tourism destinations have started to promote their commitment to the environment. Some highlight already accomplished achievements (e.g. Ski Lifts Lech in Austria1), while others present high-flying visions (e.g. the Laax winter destination in Switzerland2). Studies conducted by the German Sport University Cologne (Roth et al., 2018) have shown that environmental aspects of a ski resort are important to tourists. Moreover, ecological certification has long been recognized as a valuable tool to influence markets and has become increasingly important in tourism (Font, 2001; Buckley, 2002). This way, environmental aspects can be used to sharpen a resort’s profile and to identify and attract its respective target group(s) with ever-improving precision. However, as a result tourists are confronted with an increasing number of terms, labels and classification systems addressing so-called ‘green’ concerns, such as environmentally friendly management or sustainability.

Aside from differentiation and marketing aspects, certification systems are also used as a tool to enhance the sustainable development of ski resorts. As such, these certifications play a key role in sustainable tourism management (Font, 2002; Honey, 2002; Bien, 2007). Honey and Rome (2001) define certification as a voluntary procedure which assesses, audits and provides a written assurance that a facility, product, process or service meets specific standards. In addition, it awards a marketable logo to those enterprises that meet or exceed baseline standards. Ideally, the certification clearly demarcates sustainable from unsustainable organizations (Font and Harris, 2004). It is, therefore, considered an important tool to ensure competitiveness and differentiation, as it helps build consumer confidence (Sloan et al., 2011).

In general, there are three different categories of certificates (Sloan et al., 2011; SustainableTourism.net, 2014):

• individual concepts;

• generic environmental certifications on an international or European level (International Organization for Standardization (ISO): ISO 14001 and ISO 14004, Eco-Management and Audit Scheme (EMAS)); and

• certification by governmental initiatives (e.g. ‘Das Österreichische Umweltzeichen’/‘The Austrian Ecolabel’).

By now, a large number of individual standards have emerged and many companies have elected to adopt them (see World Tourism Organization (WTO), 2002; Sloan et al., 2011). Thereby, they make use of the varied certifying programmes in existence and ensure compliance with their sustainability standards. Overall, all credible certifications are defined by three crucial components:

1. Setting of environmental standards.

2. Third-party certification of these standards.

3. Value-added marketing or environmental communication.

In addition to the various individual concepts, the ISO has developed more generic environmental certifications that do not apply to one industry in particular (e.g. ISO 14001, which specifies the requirements for an environmental management system, and ISO 14004, which provides general guidelines for the establishment, implementation, maintenance and improvement of an environmental management system). In Europe, the EMAS also serves as an environmental benchmark and plays an important role in various economic branches (Pröbstl and Jiricka, 2009; Pröbstl-Haider et al., 2019).

However, the application of EMAS in winter tourism is still very limited. As of December 2018, only one large cable car enterprise in the Alps, namely the Schmittenhöhebahn AG in Austria, has applied this instrument. Therefore, this chapter aims to encourage cableway operators and ski area managers to introduce environmental management systems (EMSs) in their organizations by presenting different experiences and applications. To this end, we will outline key aspects in different settings by describing two separate case study areas and presenting the experiences and insights gained in each of them. With this comparison, we hope to contribute to an exchange process enabling different organizations in the industry to learn from one another.

In the following, we focus on two international certification frameworks. They are both characterized by rules and standards and have the same goals but differ in their development histories, their areas of application and – to a minor extent – in their requirements (Pröbstl-Haider et al., 2019):

• The international standard for environmental management, ISO 14001, lays down the criteria for an environmental management system and is part of a larger group of standards. It was first developed in 1996 as 14001:1996. The current version of ISO 14001 came into effect in September 2015 as ISO 14001:2015.

• EMAS stands for ‘Eco-Management and Audit Scheme’. It is a voluntary system in which businesses (as well as other organizations and institutions within EU member states) can participate. The regulation has been in effect since April 1995 and has been revised twice already. EMAS III has been in force since 11 January 2010 (Regulation (EC) No 1221/2009). With this revision, it became possible for organizations outside of the EU to participate. The general aim of the regulation (as with ISO 14001) is to promote continuous improvement of organizations’ environmental performance.

Both concepts follow the same basic principles, as illustrated in Fig. 29.1. Crucial to these schemes are the continuous improvement of EMSs and their external evaluation.

Fig. 29.1. Basic principles of environmental management according to EMAS. (Translated from Salak, 2008; original figure based on Pröbstl et al., 2003.)

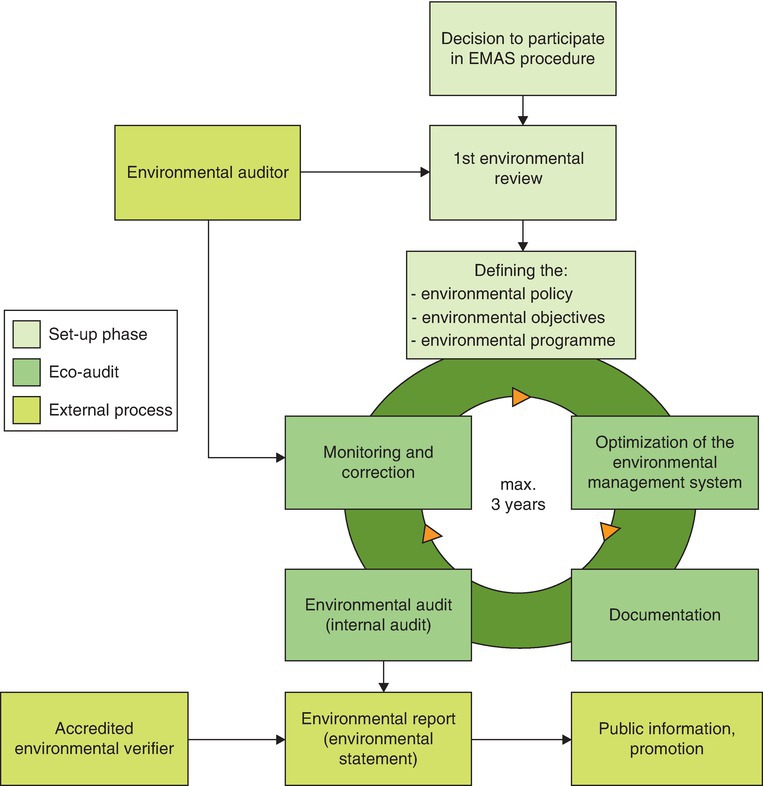

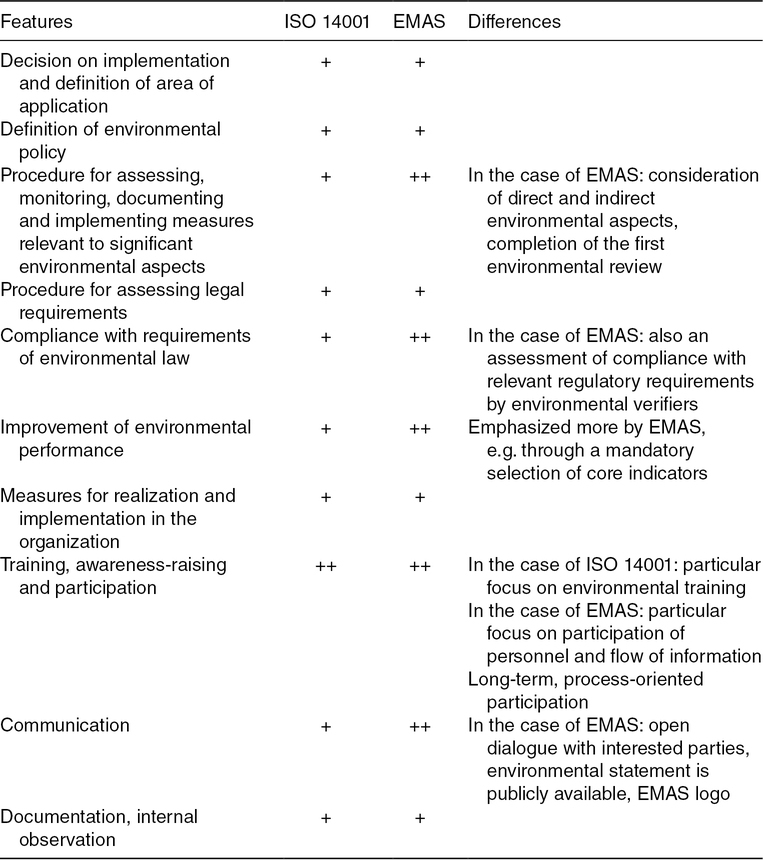

The table below gives an overview of the areas in which ISO 14001 and EMAS differ. This chapter will mainly concentrate on EMAS, since it is the more far-reaching instrument, especially when it comes to communication or to the consideration of direct and indirect impacts. Comparisons and differences are shown below (see Table 29.1).

Table 29.1. Comparison of features and requirements of ISO 14001 and EMAS. (From Pröbstl-Haider et al., 2019.)

Many businesses make use of the extensive similarities between the requirements of the two systems. They register for both ISO 14001 and EMAS certification, since this does not require much greater internal effort than meeting the requirements of just one of the two (this was, for instance, the strategy pursued by Ski Lifts Lech in Austria from 1999 until 2006).

Businesses and organizations often wish to manage various areas ‘systematically’. By using an EMS, they can monitor the quality (of products and/or services), environmental protection, work safety, and health and safety of their customers in an integrated manner.

Simultaneous implementation of ISO 14001 and EMAS is mostly chosen in cases in which the two systems are expected to appeal to different target groups (e.g. to address both customers from within the EU, as well as customers from outside who are not familiar with EMAS). Alternatively, companies may choose to register for both systems in order to thoroughly document and communicate the extensive level of examination they undergo.

In order to analyse typical challenges and environmental problems that may occur when EMAS is implemented, we selected one representative destination in the Alps with a long tradition in winter tourism and one Eastern European mountain resort representing the development of new, upcoming ski resorts.

In both ski resorts, we supported the process over a period of 2 years from the first decision in favour of establishing an EMS to the final external evaluation. We contributed to a standardized process of data collection as well as the evaluation of the collected data, and helped the respective resorts to develop first implementation measures. The similar degree of involvement in both cases allowed us to conduct action research, which is a key instrument to (i) alleviate an immediate problematic situation, and (ii) to generate new knowledge about system processes (Reason and Bradbury, 2007).

For this study, action research was chosen as the most suitable method, because this participatory approach enabled us:

• to understand the circumstances influencing practitioners’ decision making;

• to become acquainted with a common language, which in turn allowed us to join the conversation and take part in critical exchanges within the respective working groups, such as the marketing or the technical team of the respective ski resort;

• to learn more about typical internal networking and communication systems; and

• to create the right social climate for an open and critical exchange.

The aim of the applied action research approach was to help build appropriate structures for the EMS from the very outset of the planning and certification process, to set up the necessary system and competencies, and to modify the relationship of the system to its respective environment.

By forming joint collaborations within mutually acceptable ethical frameworks, action research aims to address the practical concerns of people dealing with an acute, problematic situation, as well as to contribute to the goals of social science (Reason and Bradbury, 2007). In the case of ski resort management, it is crucial to establish an understanding of how particular actors define their present situation and to reach a consensus on these starting points, so that planned actions can produce their intended outcomes.

In this chapter, we analyse the differences and commonalities between the two case studies in relation to the following aspects:

• Motivation to participate in an auditing scheme.

• Relevance and objects of environmental improvement.

• Information, marketing purposes and target groups.

• Relevance for internal management and motivation of the employees.

• Relevance of additional/external factors such as climate change.

The overall goal was to identify and analyse significant differences, which we expected to occur due to the different cultural–discursive, material–economic and social–political circumstances and arrangements in each resort. These findings can be addressed in promotional material for EMAS or considered in future fieldwork.

The ski and hiking area Schmittenhöhe, also known simply as ‘Schmitten’, is located in the mid-western part of Austria about 90 km from the city of Salzburg. It is named after the Schmittenhöhe Mountain at the edge of the Kitzbühel Alps with its peak reaching over 1900 m. At its foot lies the town of Zell am See, which has been connected to the mountain via cable car since 1927, making it the first cable car in the province of Salzburg and only the fifth in Austria at the time. Today, it is equipped with gondola cabins created by Porsche Design that offer a panoramic view of the surrounding Alps, including some peaks over 3000 m. The ski area itself lies between an altitude of 945 m in the valley and almost 2000 m at the summit station. In winter, 27 different lifts are operative and 77 km of marked ski runs are available. Additionally, the offer includes various attractions such as a ‘fun-slope’, a snow park for free skiers and snowboarders, a night-slope that is open several times a week and a snow park for children. The resort, moreover, makes an effort to engage the tech-enthusiasts among its guests by providing a free of charge GoPro rental service, a ski movie-slope, where each run can be filmed for subsequent analysis, and offering performance statistics to be accessed through a guest’s ski pass number (including the vertical metres and kilometres of slopes covered and the number of lift rides completed throughout the day). The area also features a variety of restaurants, guesthouses, mountain huts, cafés and bars catering for visitors.

A number of cable cars operate outside of the winter season as well, making the area popular with hikers. There is a wide range of hiking trails for various skill levels, and special offers include group hikes with trained guides as well as workshops (e.g. for yodelling or yoga). Additionally, there are more than 30 objects and large-scale sculptures installed throughout the area under the motto ‘art on the mountain’, providing further points of attraction for hikers.

The theme of ‘ecology’ features prominently on the ski resort’s website and the cable car company stresses that they ‘treasure nature as the underlying foundation for ski sports and hiking in the mountains’ (Schmittenhöhebahn AG, n.d.). They also describe the efforts they undertake to increase energy efficiency and to operate sustainably. Plans to expand the ski area were initially approved by the province of Salzburg but have been put on hold since 2011 due to appeals made by environmental organizations and a local initiative. Following several legal proceedings, the decision concerning the project’s Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) was amended and ultimately approved by court in April 2018 (Umweltbundesamt, 2018).

Bansko is a ski and mountain resort located in the south-western part of Bulgaria. It lies on the banks of the Glazne River at the foot of the Pirin Mountains, directly below their highest part. The town is situated about 6 km from Razlog and 150 km from Sofia, the capital of Bulgaria. The Pirin Mountains are an alpine type mountain range, its highest peak, called Vihren, reaching over 2900 m. The town of Bansko is located at 925 m above sea level, while the ski resort lies at an altitude of 990–2600 m. The area features excellent skiing and snowboarding conditions and provides all the expected infrastructure including several mountain huts and shops, a rich history, and a mix of old and new architecture. Many hotels of various standards are available and cater to different budgets. Regarding après ski activities, the resort offers a number of bars and traditional restaurants called ‘Mehana’. In the past decade, significant investments to modernize and expand existing amenities have been made by Yulen AD, the company running the ski area. Additionally, numerous new luxury hotels and other facilities were constructed around the gondola lift station in town. The ski resort attracts guests in all seasons, but its busiest time is during the winter months. Thanks to the features described above, Bansko is said to be one of Bulgaria’s best winter resorts, boasting the longest ski runs (there are 75 km of marked ski runs in total) and the richest cultural history. It has even been voted Bulgaria’s best ski resort for six consecutive years (2013–2018) at the World Ski Awards ceremony (World Media and Events Limited, 2018).

However, Bansko ski resort has also sparked heavy criticism due to it being partially located within the Pirin National Park, which is both a World Heritage site selected by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) and part of the European Union’s Natura 2000 network. Environmental non-governmental organizations (NGOs) claim that the construction of the ski area has already caused irreversible damage to nature. Moreover, a draft of the park’s new management plan as well as amendments made to the current plan are feared to pave the way for a significant expansion of the existing ski infrastructure and for extensive logging activity, which would cause further deterioration to the park’s ecosystem (Dalberg Advisors, 2018). In April 2018, the Bulgarian government’s decision to forego a Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA) for the new management plan was revoked in the first instance (Stojanovski, 2018). The amendments to the current management plan were also revoked, as they were found to violate several environmental laws (Decision 10238/27.07.18)3 (BNT, 2018).

There are several reasons why the Schmittenhöhebahn AG cable car enterprise would participate in EMAS certification. First of all, its biggest shareholder is part of the automobile industry (the Porsche GesmbH). For its management, applying an auditing system is a standard procedure to ensure product quality and to deal with legal and safety issues. In the automobile sector, this is even a prerequisite for many suppliers and subcontracting companies. However, the main motivation stems from the cable car enterprise’s self-perception and self-image. The company sees itself as a front-runner within the industry, as an enterprise that goes beyond the minimum standards and manages all environmental issues in an exemplary manner to meet the requirements of a ‘top-class ski resort’. In addition, marketing aspects and the desire to stand out from other resorts with a ‘green image’ certainly play a significant role as well.

Aside from these arguments, the enterprise also strongly emphasizes efficiency in its management. The auditing process is expected to enhance overall efficiency and save money without lowering any existing standards. The implementation of renewable energy facilities is an important aspect in this context.

In the case of Bansko, it was not an internal process that led to EMAS certification but an impulse that came from the outside. The public discussion on environmental standards of ski runs hosting international competitions prompted the FIS (Fédération Internationale de Ski/International Ski Federation) to place these aspects under greater scrutiny. Following complaints issued by the local administration and environmental NGOs, the cable car enterprise in Bansko, which (like the Schmittenhöhebahn AG) is part of a bigger consortium, decided to improve the environmental situation and apply European-wide standards including an external evaluation.

It was hoped that the application of EMAS would meet with approval at the FIS and eventually allow the resort to host annual ski racing events as part of the Alpine Skiing World Cup. Meanwhile, the significant growth of the destination – with an increasing number of accommodation options and second homes, and the construction of accompanying infrastructure – has led to changes in the guest structure. There has been a noticeable increase in Western European arrivals, which has in turn altered the guest expectations the ski resort has had to fulfil, including environmental issues and standards. Therefore, the decision in favour of EMAS was also influenced by the internationalization of guests and the need to meet the demand of future target groups and international standards.

As mentioned before, the EMAS process for the Austrian resort was not initiated in order to improve its current environmental standards, but to confirm and communicate through an external review the high level of environmental responsibility the company had already achieved. The resort’s main ski runs were created many years ago. For the few adaptations added in the recent past, the most cutting-edge technology available was used, including restoration measures to combat adverse effects on the environment through construction work. The overall condition of the local vegetation was found to be very positive, containing all typical semi-natural vegetation types as well as areas of a high to very high degree of naturalness.

Nevertheless, a closer look revealed certain environmental problems that still need to be resolved. One of them is the increase in cycling tourism across the main chain of the Alps. Biking is forbidden on the Schmittenhöhe Mountain (see Fig. 29.2) and local farmers, forest owners and hunters have been strongly opposed to the provision of any kind of infrastructure for this potential touristic target group.

Fig. 29.2. In order to avoid conflicts with hikers in summer and autumn, mountain biking is not allowed on the Schmittenhöhe Mountain. Signposts alongside hiking trails call attention to this rule, which was established in agreement with local landowners. (Photograph courtesy of Ulrike Pröbstl-Haider.)

However, as Fig. 29.3 shows, bikers still use the hiking trails on the mountain despite clear signage. In the picture, the two hikers try to avoid a conflict by walking at the edge of, or even off, the trail. This example demonstrates that the cable car enterprise has to monitor its summer tourists in order to minimize negative impacts caused by trampling or illegal activities such as mountain biking (see Fig. 29.4). Environmental impacts were mainly detected in areas with overlapping use, e.g. areas where different summer tourism activities take place, areas that are used in winter as well as summer and on slopes that are used for cattle grazing outside of the winter season.

Fig. 29.3. Although biking is forbidden, the two hikers have to walk off-trail to avoid a conflict. (Photograph courtesy of Ulrike Pröbstl-Haider.)

Fig. 29.4. Widening a trail often leads to increasing erosion and further affects nearby vegetation. (Photograph courtesy of Ulrike Pröbstl-Haider.)

A second field leading to increasing problems is the adaptation to ongoing land use changes in the Alps. In many cases, the willingness of farmers to manage areas located in ski resorts is decreasing. The steep terrain, the danger of plastic contamination in their livestock’s fodder and the comparatively low yield of hay all contribute to this trend. Only areas for cattle grazing are still requested by farmers. However, the inventory showed that the areas dedicated to hay production were characterized by particularly high biodiversity and outstanding beauty (see Fig. 29.5). Maintaining this quality as a part of the tourism product in summer was one of the key challenges and had implications for the overall summer management.

Fig. 29.5. This picture shows one of the highly valuable meadows of the Schmittenhöhe ski resort. (Photograph courtesy of AVEGA.)

The requirement to adapt overall land use (see Fig. 29.6) and to compensate for changes in agricultural management represents a common challenge many ski resorts face in the Alps.

Fig. 29.6. This picture was taken in an area where the current management approach (mulching) needs to be reconsidered in order to maintain the outstanding diversity of the aforementioned meadows. (Photograph courtesy of Ulrike Pröbstl-Haider.)

In contrast to the Alps mountain resort analysed above, most of the slopes in Bansko have only been developed in recent years. In Bansko, there is a shortage of experienced firms and enterprises specializing in mountain resort development, as well as a lack of knowledge transfer between science and the wider public. Still, the technical equipment is of excellent quality and the safety standards for skiers and personnel are the same here as they are in Western Europe. However, knowledge about vegetation, soil conditions and the management of water on slopes is lagging behind. There is also little local history and traditional know-how available on how to construct and maintain stable and attractive ski runs. Consequently, the review and auditing process focused first on significant improvements to slope stability and on the prevention of further erosion (see Fig. 29.7). Second, it addressed the regeneration of local vegetation, and, third, it attended to the required improvements in water management.

Fig. 29.7. This picture shows the construction of a double ‘Krainerwand’ to stabilize the flank of a steep slope. (Photograph courtesy of Ivan Hadjiev.)

The recultivation and regeneration of many slopes were achieved by adapting the seed mixture used and by improving the measures to reduce erosion. The following pictures provided by the enterprise managing the Bansko mountain resort show the differences between the situation before and after this intervention, and underline the effectiveness of the auditing process (see Fig. 29.8 and Fig. 29.9).

Fig. 29.8. A recultivation area next to a ski lift, picture taken on 29 June 2011. (Photograph courtesy of Ivan Hadjiev.)

Fig. 29.9. The same area showing the result of successful recultivation efforts only 4 months later, picture taken on 25 October 2011. (Photograph courtesy of Ivan Hadjiev.)

Thanks to an efficient knowledge transfer process and the substantial involvement of the local team, significant improvements could be achieved. Nevertheless, it will take at least another 20 years to reach semi-natural conditions, provided that the initiated management measures (tailor-made to suit Bansko’s specific conditions) will be continued.

Given its main motivation, as laid out in Section 29.4.1, it comes as no surprise that the cable car enterprise running the Austrian resort has been targeting the media from the very start, presenting their new measures as the result of their long-term commitment to environmental responsibility as a ‘green business’. Press conferences with guided tours were organized and complemented by a brochure and additional information made available online. The enterprise developed information material addressing tourists and other interested members of the public – thereby complying with a stipulation by EMAS, but making additional efforts to attractively design and regularly update the provided information. The enterprise has even received an award for the quality of their publicly available environmental statement.4 This award was used, in turn, to communicate the company’s environmental achievements and commitment to the public.

The marketing concept of the resort is based on the message that skiing there does not harm the environment, since, throughout its entire management system, measures are taken to protect the local environment as best possible, as well as to minimize the impact on endangered species or even to improve their situation (mainly concerning plants, insects and birds). Therefore, the enterprise tends to present the certification directly to its clients. In this context it is important to note that the majority of the resort’s clients come from German-speaking countries and that they are known to care about environmental aspects in ski resorts (Roth et al., 2018).

In the Eastern European mountain resort, marketing the auditing process first and foremost targets administrative bodies and institutions, such as the Pirin National Park, the National Ministry of Environment and Water (MOEW) and environmental NGOs based in Bulgaria. The developed measures are intended to showcase the efforts that were made to protect the local environment and to enhance the revitalization of slopes and areas below ski lifts.

The auditing process, and the significant financial and personnel efforts connected to it, are also emphasized and communicated to international sports associations such as the FIS. In so doing, the resort’s operators hope that their environmental engagement will enhance the likelihood of the destination being selected to host future sporting events.

In contrast to the Alps mountain resort, the Bulgarian ski resort addresses institutional target groups, as mentioned above, rather than its guests who mainly come from Russia, Eastern Europe and the UK. The reason for this difference might be that tourists from these countries are not generally known for their interest in sustainable tourism offers, unlike their German counterparts (TUI AG, 2017).

As mentioned in the introductory section, EMAS is characterized by processes aimed at enhancing education, training, awareness-raising and participation. In many modern cable car enterprises in the Alps, such as Schmittenhöhebahn AG, participatory processes have already been incorporated into the existing management practice. However, the involvement of personnel in the auditing process still uncovered several misunderstandings and a certain degree of miscommunication between the various divisions of the enterprise. The participatory approach increased awareness of communication problems and was a precondition for introducing new modes of cooperation. Participation is also crucial for the employees’ motivation and identification with the enterprise, supports the development and implementation of innovative ideas, and leads to a higher level of self-responsibility among individuals, teams and divisions within the enterprise.

In the case of the Bulgarian ski resort, we found that an organized participatory process supported by a translator was not a common practice, and was therefore difficult to initiate. Nevertheless, the procedure also resulted in positive outcomes, such as an increase in trust and a stronger identification of employees with the enterprise.

We found the participatory approach here to be an important instrument to improve communication patterns between various divisions, to boost motivation among personnel and to strengthen their commitment. Employees felt that their opinion was important to us as well as to the enterprise, which seemed to be a new experience for them. Overall, participation and exchange were especially important for communication, but were less relevant for innovation and self-responsibility.

Exposure to climate change and the resulting vulnerability of Austrian ski resorts were seen as important issues that were discussed intensively. The auditing process even included a specific calculation of prospective climatic scenarios that also addressed existing and future options for artificial snowmaking. Furthermore, the enterprise has invested in an energy concept, as well as in photovoltaic and alternative heating systems for new buildings. Both the current rate of energy consumption and the company’s responsibility for the future were diligently considered whenever measures for the upcoming years were decided on.

The impact of climate change on a ski resort characterized by continental climate conditions was considered to be less severe than for the Alps. Therefore, this issue was of little interest for the participants in the Eastern European mountain resort. Aside from the (presently) good natural snow conditions, the resort pointed out that the cold temperatures it experienced in winter were also suitable for artificial snowmaking. The challenges they faced in reducing erosion and fostering renaturalization and restoration of slopes, alongside the administrative and legal requirements they had to meet, seemed to represent more pressing concerns in their eyes, so that climate change and CO2 emissions were not yet considered an urgent issue.

Action research is often criticized for not being sufficiently detached, neutral or independent. However, the implementation of an auditing process following EMAS or ISO 14001 necessitates a certain degree of involvement and identification with the organization concerned. The success of an action research approach hinges on an in-depth understanding of the values relevant actors prioritize, since these values guide the selection of means and goals when solving specific problems, and further steer actors’ commitment to a particular solution (Susman and Evered, 1978; Kemmis et al., 2014). In our case, the historical background of the ski resorts also played an important role and was much more significant than expected. The role of participatory processes and the involvement of employees in the Alps mountain resort certainly differed from our experience in the Eastern European mountain resort, which featured much more hierarchical structures. These structures also defined the individual employee’s understanding of their own role within the enterprise. There is simply no way of experiencing, analysing and describing these differences without becoming involved in the process. Applying action research can be one of the most effective ways of rendering the theoretical or practical knowledge the researcher possesses truly useful for practitioners and to cultivate greater openness and acceptance among them. Moreover, not only do we gain important, practically relevant knowledge from involving researchers in real-life situations, but the situation itself simultaneously evolves into a product of knowledge transfer, causing a learning process on both sides.

After drafting a joint auditing report and organizing an internal audit process, we asked both enterprises whether they were satisfied with the experience and whether they would repeat it. Both enterprises answered in the affirmative, even though the Eastern European mountain resort in 2017 was still awaiting its official national acceptance (despite a positive external evaluation).

Further discussions supported the arguments stated below, highlighting the direct and indirect advantages of participating in EMAS. These arguments have been well-documented in various other publications (e.g. Pröbstl and Jiricka, 2009).

• Establishment and qualification of an EMS through analysis, evaluation, identification of deficiencies and risk analysis (including safety and legal risks).

• Development of a GIS-based environmental monitoring system as a by-product (a form of environmental data collection that can be continued in the future).

• Establishment and step-by-step improvement of the internal environmental monitoring system, including risk management.

• Increasing awareness for ecological responsibility among the organization’s management and staff.

• Improvement of the profit and market economy situation (more relevant in the case of the Alps mountain resort than in the Eastern European mountain resort).

• Recognition all over Europe and by international associations.

This chapter summarizes the insights gained from integrated, transnational assessment procedures applied in two different contexts. Based on the principles of an EMS prescribed by international rules and standards (EMAS), the aim in both ski resorts was to define key preconditions and to provide data and recommendations for an efficient implementation. Due to the multitude of European directives that have to be taken into account, e.g. the ‘Environmental Liability Directive’ (Directive 2004/35/CE of the European Parliament and of the Council), the ‘Birds Directive’ (Directive 2009/147/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council) and the ‘Habitats Directive’ (Council Directive 92/43/EEC), environmental management in ski areas has gained significant importance, especially in the Alps and in other European winter sports destinations. Our findings show that significant environmental improvements could be achieved in both areas despite their different geographical, political and structural conditions. In both cases, the enterprises were able to save money in the long run and to improve their tourism offers. However, the expectation that an auditing process will facilitate future planning processes or foster the expansion of a ski resort is wrong. Therefore, this should not be used as an argument to promote environmental certification. Nevertheless, drawing on extensive action research, our study has shown that the idea of improving the sustainability of an organization by entering into a certification process is still valid.

1The company has established an EMS and embraces environmental protection as part of their business policy. Further details can be found under the header ‘sustainability’ on the homepage of Lech-Zürs Tourism. Available at: https://www.lechzuers.com/en/service/sustainability/ (accessed 16 July 2019).

2Laax states that it wants to become the ‘world’s first self-sufficient winter sport resort’. They have started an initiative called ‘Greenstyle’ and published several videos about their visions and aims on their website. Available at: https://www.laax.com/en/info/greenstyle (accessed 12 July 2018).

3The court ruling is available in full online (in Bulgarian) at: www.sac.government.bg/court22.nsf/d038edcf49190344c2256b7600367606/967828fa6df6795dc22582ac0023c479?OpenDocument (accessed 6 September 2018).

4The ‘Schmitten’ cable car enterprise received an EMAS award for their 2016 environmental statement from the Austrian Federal Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry, Environment and Water Management (BMLFUW). Available at: https://www.schmitten.at/de/service/presse/pressetexte/nachhaltig-erfolgreich-die-schmitten-in-zell-am-see_p3152 (accessed 4 September 2018).

Bien, A. (2007) A simple User`s Guide for sustainable Tourism and Ecotourism, 3rd edn. Center on Ecotourism and Sustainable Development (CESD), Washington, DC.

BNT (Bulgarian National Television) (2018) Court overruled the changes to Pirin National Park Management Plan. Available at: https://www.bnt.bg/en/a/court-overruled-the-changes-to-pirin-national-park-management-plan (accessed 6 September 2018).

Buckley, R. (2002) Tourism ecolabels. Annals of Tourism Research 29(1), 183–208. DOI:10.1016/S0160-7383(01)00035-4

Council Directive 92/43/EEC of 21 May 1992 on the conservation of natural habitats and of wild fauna and flora. Available at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:31992L0043 (accessed 4 September 2018).

Dalberg Advisors (2018) Slippery Slopes: Protecting Pirin from Unsustainable Ski Expansion and Logging. WWF – World Wide Fund for Nature, Gland, Switzerland.

Directive 2004/35/CE of the European Parliament and of the Council of 21 April 2004 on environmental liability with regard to the prevention and remedying of environmental damage. Available at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex:32004L0035 (accessed 4 September 2018).

Directive 2009/147/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 30 November 2009 on the conservation of wild birds. Available at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?qid=1536062433597&uri=CELEX:32009L0147 (accessed 4 September 2018).

Font, X. (2001) Regulating the green message: the players in ecolabelling. In: Font, X. and Buckley, R. (eds) Tourism Ecolabelling: Certification and Promotion of Sustainable Management. CAB International, Wallingford, UK, pp. 1–18.

Font, X. (2002) Environmental certification in tourism and hospitality: progress, process and prospects. Tourism Management 23(3), 197–205. DOI:10.1016/S0261-5177(01)00084-X

Font, X. and Harris, C. (2004) Rethinking standards from green to sustainable. Annals of Tourism Research 31(4), 986–1007. DOI:10.1016/j.annals.2004.04.001

Honey, M. (2002) Ecotourism and Certification: Setting Standards in Practice. Island Press, Washington, DC.

Honey, M. and Rome, A. (2001) Protecting Paradise: Certification Programs for Sustainable Tourism and Ecotourism. Institute for Policy Studies, Washington, DC.

Kemmis, S., McTaggart, R. and Nixon, R. (2014) The Action Research Planner: Doing Critical Participatory Action Research. Springer, Singapore.

Pröbstl, U. and Jiricka, A. (2009) Das Europäische Eco-Management and Audit Scheme (EMAS) als Instrument für einen nachhaltigen Betrieb von Skigebieten. In: Bieger, T., Laesser, C. and Beritelli, P. (eds) Trends, Instrumente und Strategien im alpinen Tourismus. Erich Schmidt Verlag, Berlin, pp. 35–42.

Pröbstl, U., Roth, R., Schlegel, H. and Staub, R. (2003) Auditing in Skigebieten. Leitfaden zur ökologischen Aufwertung. Stiftung pro natura – pro ski, Vaduz, Liechtenstein.

Pröbstl-Haider, U., Brom, M., Dorsch, C. and Jiricka-Pürrer, A. (2019) Environmental Management in Ski Areas: Procedure – Requirements – Exemplary Solutions. Springer, Berlin. DOI:10.1007/978-3-319-75061-3

Reason, P. and Bradbury, H. (2006) Handbook of Action Research. Sage, London.

Roth, R., Krämer, A. and Severiens, J. (2018) Zweite Nationale Grundlagenstudie Wintersport Deutschland 2018. Stiftung Sicherheit im Skisport (SIS), Planegg, Germany.

Salak, B. (2008) Grundlage für ein nachhaltiges Schutzgebietsmanagement im Rahmen der EMAS II-Verordnung, illustriert am Beispiel des Nationalparks Gesäuse. MSc Thesis, University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences Vienna, Vienna.

Schmittenhöhebahn AG (n.d.) Sustainable values at the Schmittenhöhebahn. Available at: https://www.schmitten.at/en/service/company/ecology (accessed 21 September 2018).

Sloan, P., Legrand, W. and Chen, J.S. (2011) Sustainability in the Hospitality Industry: Principles of Sustainable Operations. Routledge, London.

Stojanovski, F. (2018) Bulgarian environmental activists score important court victory in struggle to #SavePirin National Park. Available at: https://globalvoices.org/2018/05/02/bulgarian-environmental-activists-score-an-important-court-victory-in-struggle-to-savepirin-national-park/ (accessed 16 July 2019).

Susman, G.I. and Evered, R.D. (1978) An assessment of the scientific merits of action research. Administrative Science Quarterly 23(4), 582–603.

SustainableTourism.net (2014) Tourism accreditation and certification. Available at: https://sustainabletourism.net/sustainable-tourism/sustainable-tourism-resource/tourism-accreditation-and-certification/ (accessed 16 July 2019).

TUI AG (2017) TUI global survey: Sustainable tourism most popular among German and French tourists. Available at: https://www.tuigroup.com/en-en/media/press-releases/2017/2017-03-07-tui-survey-sustainable-tourism (accessed 19 December 2018).

Umweltbundesamt (2018) Online-Abfrage UVP-Genehmigungsverfahren. Vorhaben-Titel: Schigebietserweiterung Hochsonnberg Piesendorf. Available at: www.umweltbundesamt.at/umweltsituation/uvpsup/uvpoesterreich1/uvpdatenbank/uvp_online/?cgiproxy_url=http%3A%2F%2Fwww5.umweltbundesamt.at%2Fuvpdb%2Fpz21schema.pl%3Ftiny%3D1%26session%3DDUyYhQXHNACKIhzuG0N3SI1I%26set%3D2 (accessed 7 September 2018).

World Media and Events Limited (2018) 6th Annual World Ski Awards Winners. Available at: https://worldskiawards.com/winners/2018 (accessed 18 December 2018).

World Tourism Organization (WTO) (2002) Voluntary Initiatives for Sustainable Tourism: Worldwide Inventory and Comparative Analysis of 104 Eco-labels, Awards and Self-commitments. World Tourism Organization, Madrid, Spain.