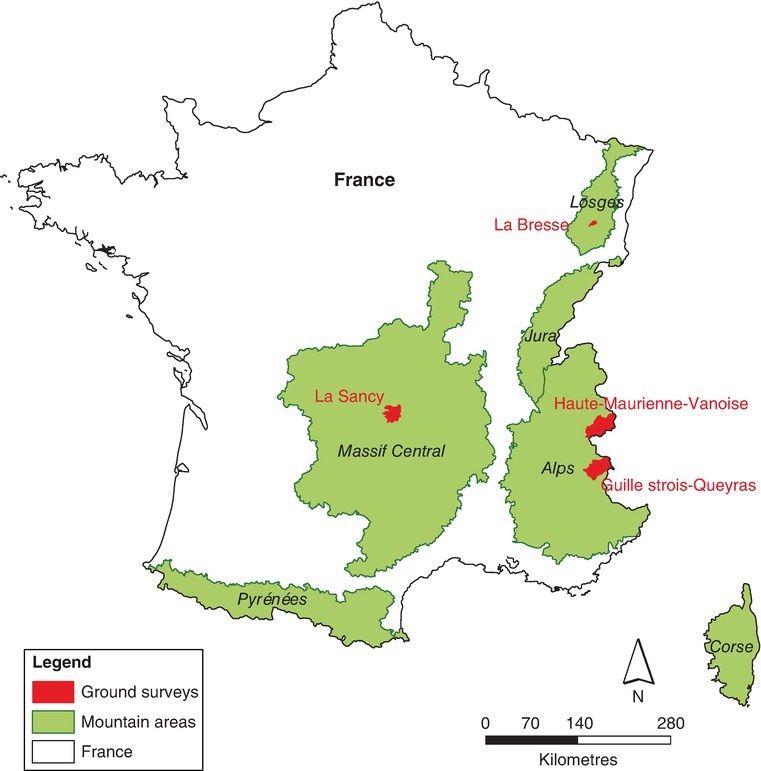

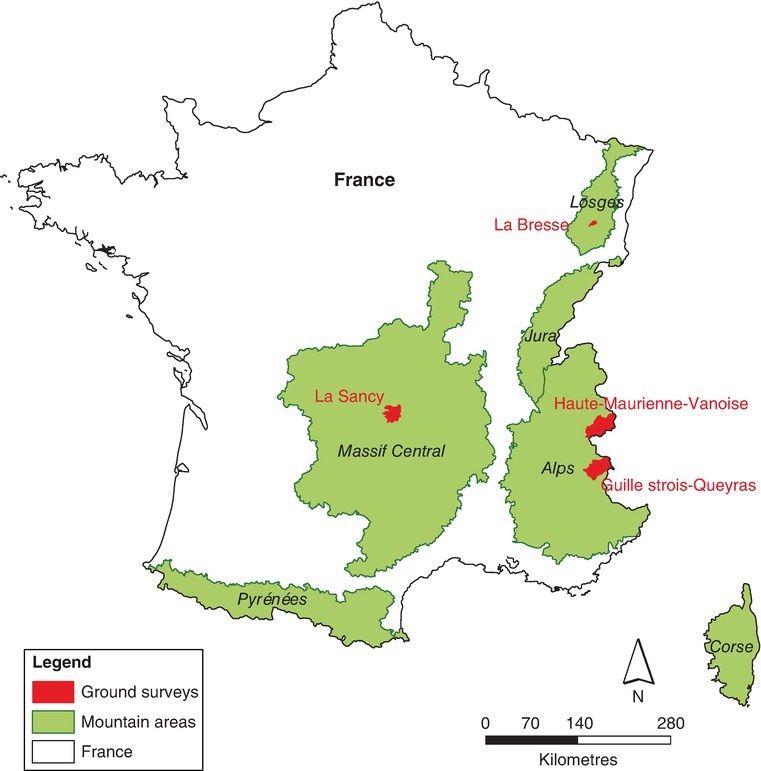

Fig 30.1. Location of the French massifs and ground surveys. (Own figure based on IGN Bd Carto®, 2016; Decree n°2004-69 of 16 January 2004 on the delimitation of the massifs.)

30 Tourism Diversification in the Development of French Ski Resorts

University of Grenoble-Alpes, Irstea-LESSEM, Grenoble, France

*E-mail: coralie.achin@irstea.fr

Since the 1930s and particularly after World War II, many mountain territories have been structured around resorts and downhill ski areas. This progressive establishment of ski resorts has provided important economic resources for the respective mountain territories (Lasanta et al., 2007). In addition to purchasing ski passes, tourists need to rent accommodation and possibly ski equipment as well as buy food, etc. Finally, operating a tourist destination involves several services, which sustain local employment and help maintain permanent – or semi-permanent – population levels in these remote and disadvantaged places. Thus, ski resorts play a role in land use planning.

However, since the creation of these resorts, the context has evolved. Global change has not spared mountain areas, which now face both climate change (e.g. François et al., 2014) and societal development (Frochot, 2016). This has resulted in the inevitable adaptation of the tourism sector. In particular, the current – and future – increase in temperatures has reduced snow cover and restricted the ability of ski resorts to stay focused on downhill skiing. Nevertheless, climate change does not affect all resorts in the same way. Low- and mid-elevation ski resorts, more than others, face difficult winters, and the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change predicts (IPCC, 2014) the disappearance of many alpine ski resorts in the next 50 years. Furthermore, ski resorts are also affected by changes in leisure behaviour. Until the 1980s, the clientele of ski resorts came for skiing, whereas today they expect other activities to be on offer (Atout France, 2011). Faced with these changes, ski resorts need to adapt themselves.

Two main strategies of adaptation have been identified. The first is mitigation, e.g. with the development of snowmaking equipment or the creation of artificial water reservoirs (Dawson and Scott, 2007; Spandre et al., 2015). The second strategy is aimed at diversifying the tourism offerings. More specifically, it aims at making available other activities based on the natural and cultural heritage of the area. Naturally, these resources are not always located next to the ski resorts, but more often in the valleys and/or the villages. Thus, the diversification of tourism involves expanding the areas comprising tourism destinations, depending on the territorial amenities available (Achin and George-Marcelpoil, 2016).

At the same time, French municipalities experienced changes in the national administrative organization. The New Territorial Organization of the Republic law (NOTRe law, proclaimed on 7 August 2015) aims to simplify the current territorial complexity, in particular by reducing the number of regions (Nuts 2) and by strengthening the role of municipality groups or ‘inter-municipalities’. Among the significant changes introduced, these inter-municipalities instead of the municipalities are now taking over the organization of tourism. This has led to the creation of an inter-municipal tourism office that aims to promote this new territory. Thus, these transformations have had an impact on tourism destinations, which were originally not structured at this scale.

In this chapter, we address the developments in tourism governance, along with the characteristics and processes that define tourism governance. In particular, we aim (i) to understand, in the French Alps context, how the organization of tourism destinations will evolve, due to both the diversification of tourism and institutional reform, and (ii) to identify the drivers of these changes. Furthermore, we show how public policies dedicated to ski resorts can help ski resorts and their territories in regenerating tourism governance. To address these questions, we used semi-structured interviews conducted with different nature stakeholders between February and October 2017 in the different mountain areas or massifs1 (see Fig. 30.1). In particular, we met with both political and socio economic stakeholders involved in tourism development and with citizens, mostly members of associations created to contribute to local tourism (e.g. associations for heritage valorization). Through the questions asked, we tried to understand stakeholders’ perceptions of tourism, the strategies they want to develop and the relationships between the stakeholders (nature, intensity, etc.) involved in the functioning of the tourism destination. We complemented the data from these 42 interviews with several tourist planning reports and contracts related to public policies adopted from the 2000s, the latest of which were signed between 2015 and 2017.

Fig 30.1. Location of the French massifs and ground surveys. (Own figure based on IGN Bd Carto®, 2016; Decree n°2004-69 of 16 January 2004 on the delimitation of the massifs.)

First, we show how the research of ski resorts has evolved (see Section 30.2). The focus on the bilateral relationship between the municipalities and the ski lift operators has shifted, and the scene has become more complex as it now integrates the various public and private stakeholders, which have become even more important once the diversification of ski resorts began. Recently, this organization was questioned by French territorial reform, creating new territories to manage tourism skills (see Section 30.3). In the last part of this chapter, we show that this development (and in particular the renewed governance imposed by the territorial reform) was anticipated by the dedicated public policies (see Section 30.3).

The great expansion of French ski areas during the 1960s and 1970s entailed the creation of more than 300 ski resorts, which were initially led by the mayor and the ski lift operator. However, the increasing uncertainties faced by the resorts and the directive to implement tourism diversification have led to a renewed analysis of ski resort governance that includes more stakeholders on an extended territorial scale.

Ski resorts are usually perceived as a unified tourism destination, whose functioning, however, relies on multiple actors. The diversity of stakeholders involved has been the subject of many articles (Bodega et al., 2004; Nordin and Svensson, 2007; Gill and Williams, 2011; Clivaz and George-Marcelpoil, 2016). These stakeholders maintain several differing relationships that contribute towards defining the type of governance followed. Thus, the corporate and community models of Flagestad and Hope (2001) are used as reference for several analyses of governance. They discuss case studies that have foundations in international governance approaches, which vary from an economic-centred model found mainly in North America to a more public–private model, which is found in European ski resorts. The governance of French ski resorts, however, does not have an equivalent model internationally. It derives mainly from the Mountain Law enacted on 9 January 1985: articles 42 and 46 of the law specify the control of tourist activities by the municipality. Seen as a public service, ski lifts and their exploitation are subject to a contract between the mayor and the ski lift operator.2 Besides the mayor, the ski resort governance system involves the various economic players, mainly the ski lift operators but also the hoteliers, the ski equipment rental companies or the restaurateurs located next to the ski resort (Gerbaux and Marcelpoil, 2006). Most often, the leadership of these ski resort areas will define the type of governance: their diversity characterizes the diversity of French ski resort governance, which involves models that are similar to the community model, where a lot of independent and various stakeholders (politics, economics) are involved in the functioning of the ski resort. Thus, a strong leadership of the mayor in the ski resorts can resemble the community model, while the strong leadership of the ski lift operator in the ski resort is not unlike the corporate model. To summarize, the initial governance of French ski resorts (since the 1980s) was implemented at the scale of the municipality giving the mayor a specific role in the leadership of the tourist destination (see Fig. 30.2). We call this pioneer organization ‘mountain tourism destination 1’ (MTD 1).

After focusing on snow and winter season, the diversification of tourism meant that the emphasis of ski resorts was not placed only on the winter season. This does not imply that the resorts turned their backs on the winter season, but that they aimed to enhance other activities that would not be dependent on the climate and on meteorological parameters. The diversification of tourism can take two main forms. First, it can lead to the development of other activities, during winter or in an all-year-round tourism. Here, tourism remains the main economic focus. The second option is to develop other economic sectors, either traditional, e.g. agriculture or industry, or non-traditional, e.g. creating tourism products like farm visits or textile industry routes. The development of new products aims to provide a ‘specific tourism offering’, as opposed to downhill skiing, which can be defined as a ‘generic tourism offering’ (Achin and George-Marcelpoil, 2016). This change in the tourism offering has in turn led to a change in the tourism scale of development: from a focus on ski resorts to a diversification of the tourism territory. This spatial extension is necessary because the new activities and resources are not necessarily, and rarely, located next to the ski area.

Consequently, a definition of the new territory is needed, according to the location of the new resources being offered. However, this change is accompanied by the necessary change in local tourism governance. Indeed, these new tourism products assume the inclusion of all providers into the network. In addition, because of the extension of the tourism reference area, the managers of other services such as real estate, restaurants or convenience stores located outside the ski resort (considered as the place of concentration of the real estate and the ski slopes) in the new territory are included in the redefined network. This arrival of new actors (i.e. tourism operators) with different statuses involves a regeneration of current tourism governance, with a possible redefinition of the leadership roles.

Other elements are needed for the transformation of a tourism destination to the new tourism scale. The most important is certainly to transmit a feeling of belonging to the new tourism destination among the stakeholders (Achin and George-Marcelpoil, 2016). This entails at least two changes. The first is related to the capacity of the actors to face competition and be able to develop complementary products and tourism offers. The second is mostly related to the promotion of this new tourism destination (Achin and George-Marcelpoil, 2016). To date, the name of the ski resort has benefited from an established, often international, reputation. However, the challenges in this context are to characterize the new tourism area (MDT 2; see Fig. 30.2) that will be organized and promoted as part of the tourism diversification plan where several ski resorts can co-exist. This set-up is based on communication between local and existing brands and on new communication support of the destination.

In practice, different strategies have been observed, among which we present two opposite approaches to tourism diversification. The first example is the ski resort of La Bresse, in the Vosges Mountains.3 This ski resort represents the main tourism activity of the territory and is similar to a corporate model where the cable car CEO owns the lifts, restaurants, real estate and ski-rental store. Tourism diversification was introduced by both the ski resort and the tourism office of the municipality but did not lead to a renewal in local governance. Indeed, although several activities were added to the tourist brochure, this was not accompanied by a commonly defined tourism strategy. On the contrary, these new tourism interests were not allowed to take part in decision making by the existing tourist office members. Here, the destination promoted was larger than the ski resort, while local governance had not changed. In the ‘Massif du Sancy’ (Massif Central), the situation was very different. From 2000, the elected officials decided to group together in a new inter-municipality dedicated to tourism organization. This led to the creation of an inter-municipality tourist office and the development of a tourism strategy on this scale. Even if the new local governance is led by the ski resorts’ mayors, most of the tourism stakeholders are included.

The territorial reform related to the recent adoption of the NOTRe law in 2015 has led to important organizational and institutional changes. We present two of the measures: the systematization of the inter-municipalities (LAU 1) and the attempt to rationalize the distribution of powers between the different institutions.

The development of the inter-municipality aims to include all municipalities within a broader group, considered important for streamlining and pooling of local public expenditure. The size of these inter-municipalities has increased and set a minimum of 15,000 inhabitants, except for mountain municipalities,4 for which a lower number is allocated (5000 inhabitants). Even if this small size is met, however, the number of inter-municipalities in the Alps has decreased by almost 35% since 2015. As proposed by the prefects of the ‘Department’ (Nuts 3), the inter-municipal map has led to numerous mergers of existing inter-municipalities, de facto questioning the place of tourism in the new institutional perimeters. Indeed, tourism exists in many parts of the Alps and contributes greatly towards boosting the local economy but this does not mean that the entire territory is touristic. For example, the direct and indirect revenues generated by winter tourism represent 50% of the Savoie department’s GDP (where the larger ski resorts are located).5 Therefore, some rural and touristic areas now need to organize themselves with non-touristic and bigger municipalities: are the different municipalities not concerned by tourism activity willing to pay for expensive tourism infrastructure while the benefits primarily go to the tourism stakeholders?

The second contribution of the law that we mention here is the strengthened role of the inter-municipalities concerning tourism. So far, the municipalities had been charged with this responsibility. They could decide to create a tourist office based on the legal form that they had chosen. In addition to the mandatory missions (welcoming tourists, providing information and coordinating stakeholders), they could also be in charge of creating the local tourism policy, of realizing tourism studies, of organizing cultural events or of commercializing tourism benefits. The creation of an inter-municipality tourist office was left to the decision of the municipalities concerned, and depended on the nature of the skills to be transferred. Flexibility was the norm. With the NOTRe law, the competence of skill creation by tourist offices now lay with the inter-municipalities. This measure was met by strong opposition from elected officials of different tourism associations.6 Consequently, derogations were granted to tourist municipalities,7 to preserve the skill of tourism promotion, including the creation of tourism offices. Therefore, in mountain territories inter-municipality tourist offices co-exist with some municipality tourist offices, intending to promote (and to preserve) the ski resort’s brand, which is more highly recognized than the inter-municipality tourism brand, as said by both tourism operators and elected people (source interviews).

As pointed out earlier, all the municipalities in the mountain tourism regions now are included in an inter-municipality. The boundaries of the inter-municipalities were designed by department prefects (given this responsibility by the state). Thus, the decision did not belong to the local stakeholders. This has resulted in important distinctions between the inter-municipalities responsible for tourism diversification (described as MDT 2) and the new inter-municipalities that have ‘lawful authority’ to organize tourism.

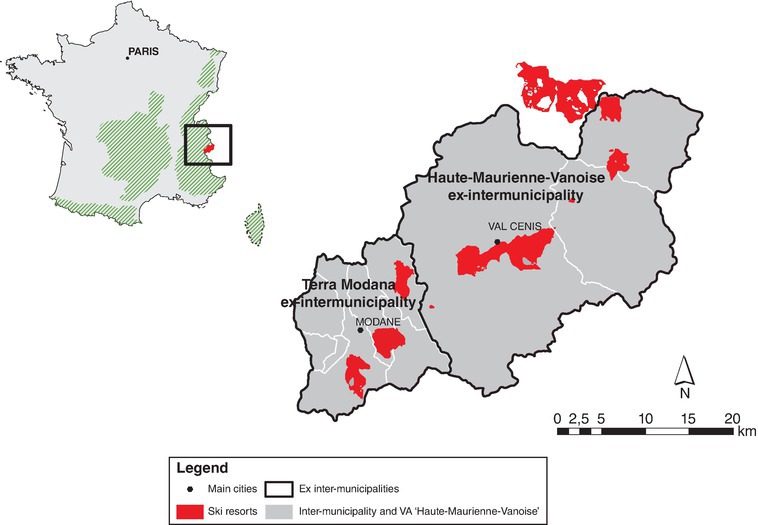

One example can be found in the ‘Haute-Maurienne’ valley. Until the reform, this territory was structured in two different inter-municipalities: the inter-municipality of ‘Haute-Maurienne-Vanoise’ and the inter-municipality of ‘Terra-Modana’ (see Fig. 30.3). The first is located at the top of the valley and has three middle-sized downhill ski resorts. Tourism is the most important component of the local economy, with agriculture in a less important role (source interviews). An inter-municipality tourist office was created in 2010 to promote the ‘Haute-Maurienne-Vanoise’8 tourism destination. Since then, the stakeholders have created a tourism organization at this territorial scale. The Terra-Modana inter-municipality, for its part, is located further down the valley. It was developed around two main economic sectors: industry and tourism.

Fig. 30.3. The Haute-Maurienne-Vanoise inter-municipality. (Own figure based on IGN Bd Carto®, 2016; IRSTEA Bd Stations, 2017; IRSTEA Bd EV, 2018.)

The industrialization of Modane, the main city, started in the early 20th century (Chabert, 1978). After the crisis in industry, tourism was developed with the creation of three middle-sized ski resorts in this inter-municipality. Unlike the Haute-Maurienne-Vanoise inter-municipality, tourism organization was maintained at the municipality level. Three tourism offices were created in the three municipalities with ski resorts. Despite the different organization of tourism between the inter-municipalities of Terra-Modana and Haute-Maurienne-Vanoise, the diversification of tourism in both cases is implemented at the scale of the inter-municipalities, under the management of the public actors. Indeed, the elected stakeholders (and the authorities of the two inter-municipalities) sought harmonization, with the development of a tourism strategy in each of the two inter-municipalities, corresponding to the MDT 2. In 2017, the implementation of the NOTRe law led to a merger of the two inter-municipalities. Today, tourism skills have been transferred to the new inter-municipality with the main consequence being the creation of a unique tourist office at the scale of the new inter-municipality, which became the MDT 3. Thus, the work initiated for the diversification of tourism has to be continued at this new scale with, inevitably, some tensions between stakeholders. First, the role of tourism in the economy and the efforts deployed for its development differed between the two inter-municipalities. Then, the replacement of the municipal tourist offices by an inter-municipality tourist office led to opposition by some stakeholders, who used to be organized at an infra-territorial scale. In this mountain territory, the institutional reorganization surely made sense in terms of tourism destination and was facilitated by the intermediary creation of the MDT 2 especially in Haute-Maurienne-Vanoise (which introduced an inter-municipality function).

During the 1960s, the French state supported the creation of ski resorts. Twenty years later, with the succession of three snow-free winters, public policies were adopted to support these ski resorts. After targeting the management of ski resorts, dedicated public policies focused on tourism diversification of the resorts.

Tourism development has been a responsibility of public actors for a long time. Since the introduction of annual paid leave, the state has helped create the third-generation ski resorts,9 while other institutions have supported the creation of access roads. After this initial creation period, the ski resorts moved to a management phase. In the 1970s, they started facing difficulties, such as poor sales of real estate, market saturation or the well-known three snow-free winters at the end of the 1980s. In reaction, the public authorities, and especially the regions and departments,10 adopted public tourism policies dedicated to ski resorts. First, the policy adopted by the ex-Rhône-Alpes region (1995–2000) aimed to support ski resorts in strengthening their management to implement an enterprise organization, by ‘fostering the transfer of its methods and organisations or by fostering the grouping of the numerous stakeholders’ (Conseil Régional Rhône-Alpes, 1995). In addition, these policies helped improve the reliability of snow cover with the funding of snowmaking installations.

The renewal of this policy from 2006 to 2012 marked an important turning point in defining the future of ‘mid-elevation ski resorts’ (George and Achin, n.d.). Tourism diversification, which constituted a minor objective in the past, became the most important goal. To this end, only inter-municipality territories, natural and regional parks, or other groupings of municipalities could be candidates. This represented a major development in policy, with aid not focused only on the ski resorts; candidates had to additionally develop a long-term tourism strategy. This led to the labelling of 27 ‘valley areas’ (VA). In the northern Alps region where this policy was confined, the VAs were mixed up with MTD 2, corresponding to the tourism diversification territory. The policy’s requirements for forward planning provided the territory with a framework in which to organize their future tourism. Indeed, one of the main difficulties for tourism stakeholders was to move beyond the short-term management, which corresponds to a limited management to current or urgent business. The requirement to establish a tourism strategy (without which the territory is not eligible for the financial support) required moving beyond the arguments of lack of time, lack of competences and/or vision for the future of tourism. The VAs public policy acted as a support for the renewal of the local governance of tourism, proposing a framework in which to collectively imagine and elaborate on an alternative to the snow-focused tourism offerings.

Current public policy (2014–2020) is aimed at both the imperative of tourism diversification and the inter-municipal dimension of the projects. First, while tourism diversification was seen to encompass all tourism activities not related to downhill skiing, it is now considered as the tourism valorization of natural and cultural heritage. For example, this has led to the creation of hiking trails and chapels or artisan roads. The second aspect of the policy is related to the territories admitted as candidates for public funding. The previous policies had introduced the inter-municipalities approach, and the current policies pursue this approach by further developing it. After the initial experiences, some VA mergers and extensions were proposed by the policy representatives. The underlying idea was to define more relevant and especially larger tourism territories. The boundaries of these new VAs have taken into account the still temporary outlines of the inter-municipalities resulting from the NOTRe law.

In Haute-Maurienne-Vanoise, territorial reform has led – as we have seen – to the merger of the two inter-municipalities, which previously organized tourism activity. Here, it is important to underline the significance of the public policies dedicated to mountain tourism, and especially the current policies. Indeed, by encouraging the two inter-municipalities to unite as one candidate, the policy leaders have anticipated the legal obligation to merge the inter-municipalities. To elaborate on a common strategy, they decided to gather together the tourism projects from all the municipalities. Subsequently, they categorized and prioritized these projects to achieve a shared tourism strategy, validated by the policy leaders. During this process, the various actors became acquainted and learnt to work together. In addition, tourism planning helped to win the stakeholders’ acceptance of the creation of a common tourist office. With the definition of a common strategy and a shared tourism destination brand, there has not been a desire to preserve local tourist offices.

In the ‘Guillestrois-Queyras’ VA (see Fig. 30.1), the situation is rather different. Here too, two VAs were created in 2006, one in the ‘Guillestrois’ and the other in the Queyras Regional Nature Park. At the request of the public authorities and to prepare for territorial reform, these two VAs merged when public policy was renewed. In January 2017, the two inter-municipalities (corresponding to the two ex-VAs) also merged. After 1 1/2 years of existence, a distinction remains between the two territories. The head of tourism notes in particular the preservation of the two tourism destinations and the struggle to initiate a common tourism organization. Although an inter-municipality tourist office has been created, two of the ski resorts have decided to preserve their municipality tourist office.11 Elaboration of the tourism strategy and the related action plan have facilitated the common work of all the local elected officials. However, the reduction in financial resources has led to a demobilization of these stakeholders and a loss of the networking aims pursued by the public policy.

To conclude, ongoing studies confirm the diversity of the governance models of French ski resorts. Indeed, the directive for tourism diversification, related to climate change, has forced ski resorts to renew their organizational dynamics. Thus, these current dynamics still range between the original tourism governance focused on the ski resort, the winter season and the ski lift operator, and, since the 2000s, a tourism diversification governance that aimed at creating a new tourism destination larger than the ski resort, involving more stakeholders and with the perspective of all-year-round tourism.

These different dynamics also highlight the important factors that are needed for tourism diversification and more generally for the future of ski resorts. First, the stakeholder networks and their expansion with ‘new’ stakeholders questions the future of the leaders in place, their nature but also their renewal. The second point highlights the limits of the tourism destination. Questions regarding this include: How to define a good territorial balance to preserve the unity of the destination? How to achieve a structural dimension that can be extended beyond the ski resorts? And how to preserve tourism’s interests over a large area, where potentially the mountain (and its tourism stakes) is marginal, compared with cities included in the same inter-municipality?

The findings in this chapter are based on a project (EValoscope) financed by the European Union with the cooperation of the Regional European Development Fund, under Strategic Objective 1 of the Interregional Operational Programme 2014–2020 for the Alps Mountains.

1Unless otherwise specified in the text, the term ‘Alps’ refers to the French part of the Alps.

2These contracts are only needed in the case of private exploitation of the lifts; the municipality can choose to directly manage this activity.

3France has five ‘massifs’ on its mainland territory: the Alps, the Jura, the Massif Central, the Pyrenees and the Vosges. They have been defined by the Mountain Law of 1985 and include mountainous municipalities that have significant disadvantages involving more difficult living conditions and restricting the exercise of certain economic activities.

4This specific size also concerns other inter-municipalities, with a low population density.

5Le Tourisme en Savoie. Available at: www.observatoire.savoie.equipement-agriculture.gouv.fr/Atlas/5-tourisme.htm (accessed 1 February 2019).

6See for instance Laurent Wauquier, President of the National Association of Mountain Elected (ANEM) keynote address during the 31th Congress of the Association (15–16 October 2015). Available at: www.anem.fr/upload/pdf/Discours_ouverture_de_Laurent_WAUQUIEZ__President_de_l__ANEM__depute_de_la_Haute_Loire_20151126112222_31eme_Congres_Discours_ouverture_LW.pdf (accessed 10 October 2018).

7Ranking in tourism municipalities is realized by prefectural order.

8‘Vanoise’ refers to the Vanoise National Park, which is partly in the territory of the inter-municipality.

9The third generation of ski resorts was created in the 1960s ex nihilo with the support of the French state, in optimal places for downhill skiing. Their construction optimized tourism by creating a snow industry: real estate was vertical and was located with all the services at the convergence point of lifts and slopes (Cumin, 1970).

10The 1982 laws on decentralization gave local authorities new prerogatives and greater resources. Among them, the departments and regions (Nuts 2 and 3) henceforth had a capacity in town and country planning.

11By way of exception, the NOTRe law allows the tourism-classified municipalities and resorts to maintain their tourist office.

Achin, C. and George-Marcelpoil, E. (2016) The tourism diversification in French ski resorts: what are effective drivers for sustainable tourism in mountain resorts? In: Lira, S., Mano, A., Pinheiro, C. and Amoêda, R. (eds) Tourism 2016: International Conference on Global Tourism and Sustainability. Green Lines Institute for Sustainable Development, Barcelos, Portugal, pp. 11.

Atout France (2011) Carnet de route de la montagne: Pour un développement touristique durable des territoires de montagne. Collection Marketing touristique. Atout France, Paris.

Bodega, D., Cioccarelli, G. and Denicolai, S. (2004) New inter-organizational forms: evolution of relationship structures in mountain tourism. Tourism Review 59(3), 13–19. DOI:10.1108/eb058437

Chabert, L. (1978) Vallées montagnardes et industrie: le cas des Alpes françaises du nord (Mountain valleys and industry: the example of the northern French Alps). Bulletin de l’Association de Géographes Français 55(453), 187–191. DOI:10.3406/bagf.1978.5030

Clivaz, C. and George-Marcelpoil, E. (2016) Moutain tourism development between the political and administrative context and local governance: a French-Swiss comparison. In: Dissart, J.-C., Dehez, J. and Marsat, J.B. (eds) Tourism, Recreation and Regional Development. Perspectives from France and Abroad. Routledge, Abingdon, UK, pp. 93–106.

Conseil Régional Rhône-Alpes (1995) Charte ‘entreprise-station’ 1995–2000. Conseil Régional Rhône-Alpes, Lyon, France.

Cumin, G. (1970) Les stations intégrées. Urbanisme 116, 50–53.

Dawson, J. and Scott, D. (2007) Climate change vulnerability of the Vermont ski tourism industry (USA). Annals of Leisure Research 10(3–4), 550–572. DOI:10.1080/11745398.2007.9686781

Flagestad, A. and Hope, C.A. (2001) Strategic success in winter sports destinations: a sustainable value creation perspective. Tourism Management 22(5), 445–461. DOI:10.1016/S0261-5177(01)00010-3

François, H., Morin, S., Lafaysse, M. and George-Marcelpoil, E. (2014) Crossing numerical simulations of snow conditions with a spatially-resolved socio-economic database of ski resorts: a proof of concept in the French Alps. Cold regions science and technology 108, 98–112. DOI:10.1016/j.coldregions.2014.08.005

Frochot, I. (2016) Consumer co-construction and auto-construction mechanisms in the tourist experience: applications to the resort model at a destination scale. In: Dissart, J.-C., Dehez, J. and Marsat, J.B. (eds) Tourism, Recreation and Regional Development. Perspectives from France and Abroad. Routledge, Abingdon, UK, pp. 123–138.

George, E. and Achin, C. (n.d.) Implementation of tourism diversification in ski resorts in the French Alps: a history of territorializing tourism. In: Dissart, J.-C. and Seigneuret, N. (eds) Local Resources and Well-being: a Multidisciplinary Perspective (provisional title). Accepted for publication.

Gerbaux, F. and Marcelpoil, E. (2006) Gouvernance des stations de montagne en France: les spécificités du partenariat public-privé. Revue de géographie alpine 94(1), 9–19. DOI:10.3406/rga.2006.2380

Gill, A.M. and Williams, P.W. (2011) Rethinking resort growth: understanding evolving governance strategies in Whistler, British Columbia. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 19(4–5), 629–648. DOI:10.1080/09669582.2011.558626

IPCC (2014) Climate Change 2014 – Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Part A: Global and Sectoral Aspects. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK.

Lasanta, T., Laguna, M. and Vicente-Serrano, S.M. (2007) Do tourism-based ski resorts contribute to the homogeneous development of the Mediterranean mountains? A case study in the Central Spanish Pyrenees. Tourism Management 28(5), 1326–1339. DOI:10.1016/j.tourman.2007.01.003

Nordin, S. and Svensson, B. (2007) Innovative destination governance: the Swedish ski resort of Åre. The International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation 8(1), 53–66. DOI:10.5367/000000007780007416

Spandre, P., François, H., Morin, S. and George-Marcelpoil, E. (2015) Snowmaking in the French Alps. Journal of Alpine Research – Revue de géographie alpine 103(2), 1–17. DOI:10.4000/rga.2913