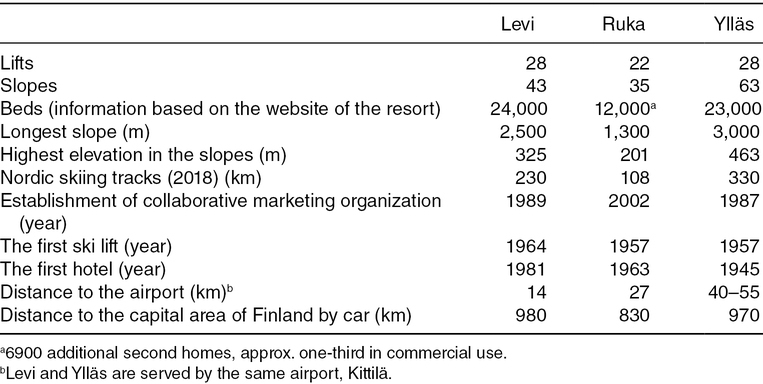

Table 35.1. Facts and figures of the case resorts Levi, Ruka and Ylläs.

Business School, University of Eastern Finland, Joensuu, Finland

*E-mail: raija.komppula@uef.fi

The aim of this chapter is to investigate stakeholders’ perceptions of the factors affecting the success of a destination, in this case the three biggest ski resorts in Finland. This study does not try to explain the success or failure. Instead, it introduces stakeholders’ perceptions of the contribution of different kinds of stakeholders to the growth and success of the ski resorts in question. Success in this case is measured by growth in overnights and turnover of ski pass ticket purchases, following Bornhorst et al. (2010). Their study is a rare example of research discussing in-depth determinants of destination success, particularly those that can be affected by the tourism enterprises and other local actors. Bornhorst et al. (2010) state that achieving success in tourism is challenging and still not very well understood. This study is an attempt to fill this gap in knowledge.

There are around 100 ski resorts in Finland, the smallest of them having only one lift and two slopes, while the largest resort, Levi, has 43 slopes and 28 lifts and 230 km of cross-country tracks (Finnish Ski Area Association, 2018). There are approximately half a million active downhill skiers in Finland, and some 1.3 million active cross-country skiers – ‘active’ meaning that the person has been doing the activity during the ongoing season (Finnish Ski Area Association, 2014, 2016). A Finnish skier spends an average of 9 days downhill skiing per year, but would prefer to ski 16 days. A total of 27% of the Finnish downhill skiers are loyal to one ski resort, but more than half of the skiers visit several domestic ski resorts during a season (Finnish Ski Area Association, 2016). The most important ski resorts are located in the Finnish Lapland, in a distance of 800–1100 km from the main domestic market, i.e. the capital area. Domestic skiers comprise the most important target market for all the Finnish ski resorts, and especially those located in Lapland attract ski tourists from all parts of Finland.

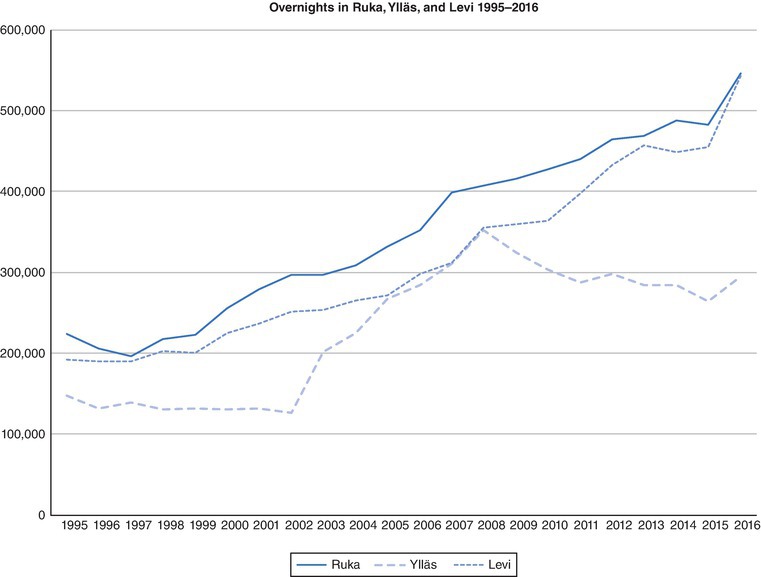

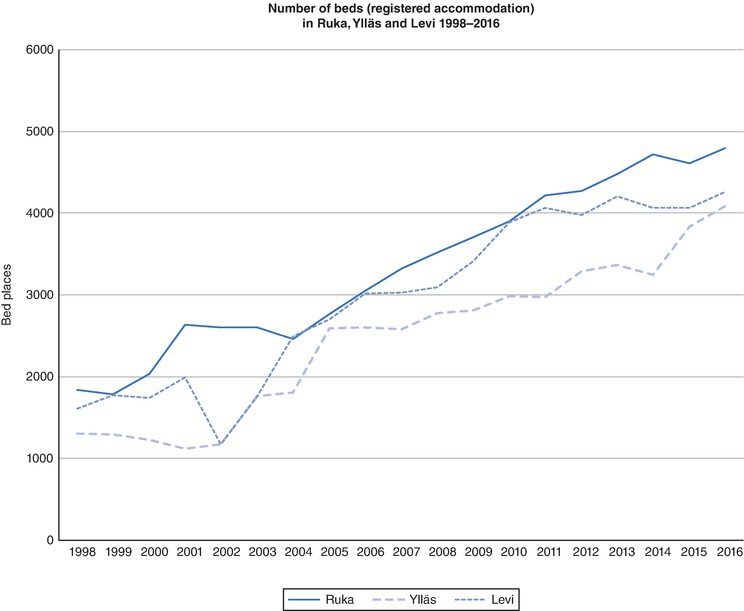

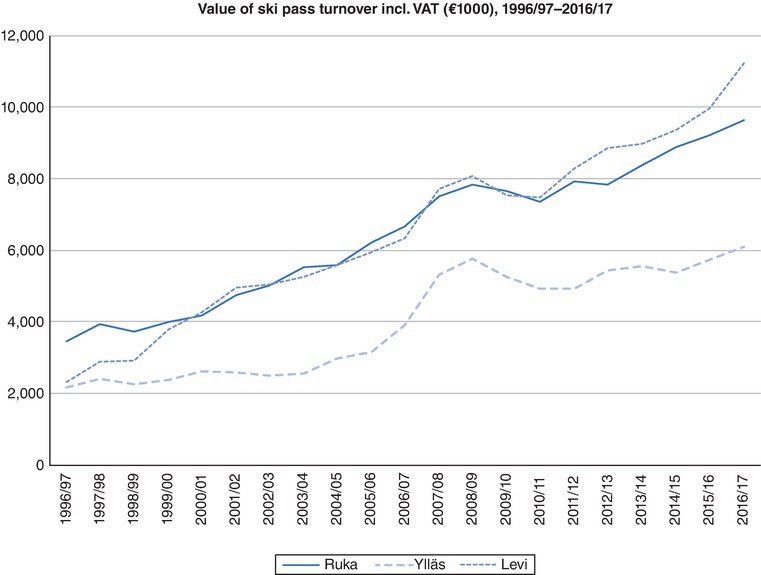

This chapter presents a multiple case study from northern Finland, comparing the three biggest ski resorts (measured by ski lift turnover), namely Levi, Ruka and Ylläs. Measured by value of ski pass turnover, during the 1996/97 season both Ylläs and Levi had a turnover of around €2.2 million, with Ruka having a turnover of almost €3.5 million. Over the next 10 years Levi caught up with Ruka, and in the 2006/07 season both had a turnover of around €6.5 million, and Ylläs less at €3.9 million. Similar kinds of development can be seen from the overnight statistics, particularly after the year 2008, when the overnights in Ylläs started to decrease and those in Levi and Ruka increased rapidly. The growth in the number of available beds in these resorts has been quite steady in all the resorts, as has the fluctuation of room occupation rates. Based on these facts it can be argued that Levi and Ruka have been able to increase significantly their popularity among tourists, while the growth of Ylläs has been much slower. Nevertheless, if we compare the natural resources of Ylläs, measured by highest elevation in the slopes, length of the slopes or number of slopes, or even the amount of cross-country skiing tracks, Ylläs would be the number one.

According to previous studies, the most important attributes affecting consumers’ ski destination choice are price (e.g. Richards, 1996), snow quality and diversity of the ski terrain (e.g. Godfrey, 1999) and the overall destination image (e.g. Ferrand and Vecciatini, 2002). As it can be argued that the market, as well as snow and weather conditions are more or less the same for Levi, Ylläs and Ruka, all of them being located in northern Finland, the attractiveness to the customers appears to be related to the perceived image of the resort, and dependent on the activities of the stakeholders in the resort (Komppula and Laukkanen, 2016). Komppula’s (2014) findings in a Finnish rural destination emphasize the importance of different stakeholders, especially entrepreneurs and municipalities, in the development and success of a destination. As several studies (Bregoli and Del Chiappa, 2013; Komppula, 2014; Pforr et al., 2014; Zehrer et al., 2014) demonstrate the importance of coordination of activities, and collaboration between the stakeholders in destination success, this chapter focuses on collaboration and leadership in the destination.

Pike and Paige (2014) raise the question of ‘who’ should take the responsibility for the planning and marketing of a destination. This is relevant in community-type destinations, in which there is typically not one single organization that has the power or the acceptance to control other destination stakeholders (Volgger and Pechlaner, 2014). Unique characteristics of the destination affect the way in which cooperation and leadership form and establish in a destination (Beritelli et al. 2007; Timur and Getz, 2008; Kozak et al. 2014; Tuohino and Konu, 2014).

In Finland, it is the local governments and/or the provincial authorities that carry the responsibility of tourism destination policy making. If these decision making organizations do not have a common vision and strategy in terms of destination development, it can lead to competing development projects and fragmented marketing projects executed by neighbouring municipalities, particularly, if there are no destination marketing organizations in the region (Komppula, 2014). The interviewees in Komppula’s (2014) study considered that municipalities should not take care of operative marketing but rather provide the basis for it by giving financial support to the destination marketing organization’s (DMO) marketing activities. Another role that the public sector could have is to enforce stakeholder engagement. The public sector should create a favourable entrepreneurial climate that supports entrepreneurs’ actions and attracts investments to a destination (Komppula, 2014). The findings of Presenza and Cipollina (2010) from Italy suggest that the firms may regard the public sector, such as tourism bureaus and regional governments, as even more significant for their management and marketing undertakings than private stakeholders (Presenza and Cipollina, 2010). This may also apply to Finland, which has no uniform structure of organizations involved in the tourist industry, but regional- and local-level structures differ between regions, meaning that in some rural tourism destinations no DMOs even exist (Tuohino and Konu, 2014).

DMOs are often regarded as having the coordinating role in destinations (Beritelli et al., 2015). Although the coordinating role of the DMO is widely emphasized in destination marketing and management literature (Komppula, 2014), Franch et al. (2010) suggest that there is not one actor responsible for the destination management but rather a destination is regarded as a network of actors affecting each other. Several authors highlight that a DMO’s role as a destination coordinator is dependent on the roles of the individuals that are affiliated to it (e.g. Strobl and Peters, 2013; Beritelli et al., 2015; Komppula, 2016), Beritelli et al. (2015) calling them a destination’s elite network. In other words, it is the actors linked to the DMO that drive the coordination in a destination, and a DMO is an organization that constitutes these actors (Beritelli et al., 2015). This would mean that the DMO itself is not the focal point but rather the people that operate in it.

Pechlaner et al. (2014) emphasize that understanding destination leadership is crucial for any tourism destination. While destination governance focuses on destination structures and norms, destination leadership has more to do with individual actors, their visions, capability to influence other actors and capability to create relationships (Beritelli and Bieger, 2014). Several authors (Hankinson, 2012; Strobl and Peters, 2013; Beritelli and Bieger, 2014; Komppula, 2014, 2016) state that destination leadership is accredited to individuals within a destination. A lack of creative, committed and risk-taking entrepreneurs (Russell and Faulkner, 1999, 2004; Komppula, 2014) or municipality officials or politicians (Komppula, 2016) can inhibit a destination’s overall development. Destination leaders are often charismatic individuals, described as passionate, intuitive, visionary and creative, and often able to predict future market trends and product opportunities (McCarthy, 2003; Komppula, 2016).

Destination leaders need to be able to motivate and inspire other destination stakeholders to strive for the common goals of a destination (Pechlaner et al., 2014) and build trust among stakeholders (Beritelli and Bieger, 2014). According to Beritelli and Bieger (2014), it is essential that leadership stems from the destination or region itself and a common objective of pulling all the actors together should, therefore, be the success of the destination. Kozak et al. (2014) note that destination leadership is strongly impacted by locality, i.e. being local. They suggest that destination leadership should be personalized to each destination to better serve its purpose and to be more successful, by respecting the local networks as well as the history of the networks.

To sum up, according to the literature, the determinants of destination success seem to be location, accessibility, attractive product and service offering, quality visitor experiences and community support, the latter referring to collaboration and leadership in the destination. Location as well as attractions based on nature and culture are more or less given, and regarded as comparative advantage, but the other determinants may be influenced by the activities of the actors in the destination. Hence, in this study stakeholders in the three biggest ski resorts in Finland are interviewed in order to explore their perceptions of the determinants of success in these particular destinations. The literature discussion above will guide the data analysis.

Levi ski resort is located in the village of Sirkka in the municipality of Kittilä. The first steps towards organized tourism activity were taken in 1964, when the municipality of Kittilä purchased some land near the Levi fell. The mayor of the municipality in 1963 had a clear vision of how to turn Levi into a veritable holiday town. When the land had been purchased, investments were made in the first ski lifts and a valley station. In 1976, two local entrepreneurs and representatives of the municipality of Kittilä established a ski lift company to maintain and develop the ski slopes. The mayor also had a decisive role in the process of persuading a large Finnish trade union to build its holiday venue, a hotel, at Levi in 1981. Due to its challenging traffic connections and remote location, building an airport in Kittilä became one of the key issues in the development of tourism at Levi. Collaboration among the mayor, local tourism entrepreneurs and trade unions led to the opening of an airport in Kittilä in February 1983.

The municipality of Kittilä launched a 3-year tourism development project in 1987. It aimed to create an all-year programme service centre in Levi to bring together the disordered services. One of the key results achieved by the development project was a general land use plan for the Levi area. The area could be developed based on this plan. Levin Matkailu Oy, a tourism company owned by tourism and accommodation industry entrepreneurs, representatives of other businesses and the municipality of Kittilä, was established in 1989.

Finland’s first gondola lift opened at Levi in the early 2000s. In 2000, Levi hosted the men’s European Cup Alpine skiing competition in slalom and giant slalom. After this competition, Levi was permanently added to the European Cup calendar. In November 2006, Levi hosted the opening competitions of the women’s and men’s slalom season, and after this event, Levi was named as the opening venue of the World Cup until 2013. The slope company invested a total of €12.5 million in a new service building and two new lifts during the 2007/08 season. Congress and Exhibition Centre Levi Summit opened in 2007. Over the years, Levi has grown into a full-service tourist destination that is open all year round, with more than 200 companies being active in Levi.

Ruka is located in the municipality of Kuusamo and is the second largest ski resort in Finland measured by the number of ski lift tickets sold. The Ruka-Kuusamo area has approximately 600 km of snowmobile routes, 160 km of hiking routes and 350 km of canoeing routes. Around 1 million tourists visit the Ruka-Kuusamo area each year. The municipality of Kuusamo is also one of the most popular second-home sites in Finland, with almost 7000 holiday homes. Furthermore, the region is home to the Oulanka National Park, with some 200,000 visitors a year (Metsähallitus, 2018).

The beginning of the story of Ruka ski resort dates back to 1954 when some 20 people interested in winter sports started clearing the slopes of the fell at Ruka, and the first Finnish championships in alpine skiing were organized in Ruka in 1956. Important actions for the development of Ruka were implemented in the 1970s, when entrepreneurs in Ruka and the municipality started to make systematic investments to generate a competitive edge and to develop Ruka into a versatile, top-class ski resort. The cooperation between the Ruka destination and the municipality of Kuusamo was especially important in the early 1980s when land use plans that would remodel the entire area were made at Ruka. At the end of the 1980s, an international airport was constructed in Kuusamo. The first Freestyle Ski World Cup was arranged at Ruka in 2005. Since late November 2005, Ruka has hosted Ruka Nordic, the season’s first World Cup event in cross-country skiing, ski jumping and Nordic combined.

The conscious branding of Ruka started in the 1980s, based on the skiing product, meaning that Ruka ski resort can be considered the first real tourism brand in Finland. The ski lift company owned the brand logo and the other companies paid their share of the marketing expenses to the lift company’s bank account. In 1999 the municipality and the companies of Ruka started joint marketing with a desire to generate more powerful marketing communications by combining the investments in marketing the summer offering of Kuusamo and the winter offering of Ruka. Hence, the concept of destination was broadened to contain the whole municipality of Kuusamo including the Ruka resort. In 2002, the largest tourism enterprises in the region joined forces with the municipality of Kuusamo to establish the Ruka-Kuusamo Tourism Association, aiming at promoting year-round tourism activities under a joint brand of Ruka-Kuusamo. The demand for incentive travel collapsed in 2008, after which some of the companies in Ruka were obliged to find new target markets. During 2014, reorganization of the board of the tourism association occurred, and a renewal of the Ruka-Kuusamo brand logo was presented. The change back to a brand logo focusing on Ruka caused some disagreement with the Ruka area tourism industry and other fields of industries as well as with the municipality.

Ylläs fell is located in the northern part of Kolari municipality in Lapland, Finland. The Ylläs ski resort area entails the villages of Äkäslompolo and Ylläsjärvi, which are located on opposite sides of the fell. Ylläs is located near to the Pallas-Yllästunturi national park, which is, based on the number of visitors, the most popular national park in Finland, with some half a million visitors per a year (Metsähallitus, 2018). There are two ski lift companies on opposite sides of Ylläs fell, which together comprise 63 ski slopes and 28 ski lifts. The longest slope in Ylläs fell is 3 km long and the elevation in the slopes reaches 464 m at the highest point.

Tourism in Ylläs has its roots in the 1930s when local people started accommodating tourists in their homes. The first actual hotel in Äkäslompolo, Hotelli Humina, was built in the 1950s. The first ever ski lift was built on the Ylläs fell in the 1950s by the municipality on the Äkäslompolo side of the fell. Later, in the 1960s and 1970s Yllärjärvi residents played a major part in building the first lift on the Ylläsjärvi side of the fell, and at the beginning of the 1980s the villagers established their own ski lift company in Ylläsjärvi. In 1985 two private entrepreneurs, from outside the region, bought 60% of the shares of the ski lift company in Ylläsjärvi, and later also bought the rest of the shares. The owners started investing strongly in new slopes and ski lifts until the beginning of the 1990s. On the other side of the fell, the ski lift company had moved from the hands of the municipality to a private company, which experienced a bankruptcy during the 1990s recession. The ski resort on the Ylläsjärvi side tried to buy the bankrupt company but the offer was not accepted. Until the year 2000, the Äkäslompolo ski resort was owned by a property management company. The new rise of the Äkäslompolo ski resort started when the current owner, a hotel chain, made major investments in the facilities during 2007 and 2008. For the customer, the fell has been one ski resort from 1984, when the companies on the opposite sides of the fell agreed to offer a joint ski ticket.

In 1987 the first joint marketing and centralized booking office was established in Ylläs with 150 shareholders. In the 1990s, another central booking office was established by a private entrepreneur, creating the setting of two central booking offices in the area. Later on, the joint marketing fell apart and the marketing of the area was externalized to a provincial party (Lapland Tourism Marketing organization). The situation changed again in 2003 when the new joint marketing organization (Ylläs Tourism Association) was established in Ylläs as an effort to pull together the marketing and event planning of the area as well as the maintenance of the ski tracks. Before this development, the villages, for instance, had their own separate systems for the maintenance of the tracks. In 2015, the collaboration was reorganized into two separate units: the Ylläs Marketing limited company having its focus on the marketing of the destination and the other (association) focusing, for instance, on the maintenance of the skiing tracks.

The accessibility of Ylläs experienced major enhancements in the 1980s when the airline and train connections to the area were established. At the beginning of the 1990s, Ylläs was strongly growing and it was ahead of Ruka and Levi in its popularity. The recession in the 1990s, however, slowed down all investments in Ylläs. During that time, Levi and Ruka jumped ahead of Ylläs in their development and popularity. The beginning of the new century was, again, a time of growth until the economic downturn in 2008 put a stop to it once again. The recovery since then has been, to some extent, slow in comparison with Levi and Ruka.

According to a study on the images of Levi, Ruka and Ylläs by Komppula and Laukkanen (2016), Levi and Ruka attract particularly downhill skiers and social life seekers, who value good restaurants and social life activities. Families are also an important target group for both Levi and Ruka. Ylläs attracts all age groups, but particularly the elderly and cross-country skiers. According to Komppula and Laukkanen (2016), Levi and Ruka have favoured young people and children in their promotional material pictures. In the marketing materials of Ylläs, adults and families seem to be the focus. Hence, the image of Ruka and Levi seems to attract youngsters, families and party seekers, whereas Ylläs seems to be more for cross-country skiers and elderly active sports seekers. According to Konu et al. (2011) the socio-demographic development among Finnish customers may have a major role in the development of the Finnish ski industry in the future, as many Finnish downhill skiers start cross-country skiing in middle age and are then active in both.

Table 35.1 demonstrates that out of the three destinations, Ylläs and its natural surroundings seem to offer the most prominent settings for different skiing activities.

Figure 35.1 demonstrates the development of overnight stays and Fig. 35.2 the development of number of beds in registered accommodation establishments in the case resorts. Fig. 35.3 presents the value of ski pass turnover in each of these resorts.

Fig. 35.1. Registered overnights 1995–2016. (Figure by Art-Travel Ltd, based on data from Statistics Finland.)

Fig. 35.2. Number of beds in registered accommodation. (Figure by Art-Travel Ltd, based on data from Statistics Finland.)

Fig. 35.3. Value of ski pass turnover. (Figure by Art-Travel Ltd, based on data from Suomen hiihtokeskusyhdistys ry.)

As can be seen from these three figures, the development of Ylläs has been on a lower level than its counterparts Levi and Ruka. The market conditions are more or less the same for all. From the resource point of view, Ylläs could be seen as most competitive in terms of comparative advantage.

Each of the cases have been studied as an intensive case study in which the goal has been to build a comprehensive and holistic understanding of the unique history and surroundings of the case, bringing forward the distinctive aspects of each (Eriksson and Kovalainen, 2008). In each case the informants were chosen by utilizing a snowball sampling method, in which the first interviewee suggests to the researcher who could be interviewed next (Eriksson and Kovalainen, 2008). It was taken into consideration that representatives from all stakeholder groups (entrepreneurs, DMO, municipality), should be included in each sample. A description of the interviewed stakeholders is presented in Table 35.2. The first interviewee in each case was chosen to represent either the DMO or the municipality, a person who knew the history of the area well and, therefore, was able to provide information on who else could have valuable knowledge and insights on the topic.

The interviewees were asked to relate their own history at the resort, and their contribution to the development and leadership of the resort, to discuss the key events and turning points in development of the resort and, finally, to evaluate the contribution of different stakeholders (DMO, municipality, enterprises, politicians, etc.) in the development of the resort.

In the interviews of Ruka and Levi, the interviewees were not directly asked to compare the three resorts, but many interviewees did make comparisons, particularly between Ruka and Levi, but also commented on the success of Ylläs. In the interviews at Ylläs, as the final question the interviewees were shown the figures concerning the growth in overnights and ski pass turnover in the three resorts, and the interviewees were asked to comment on the figures.

Important sources of information in each case study were newspaper clippings, which were available in local libraries and/or local newspaper archives. Additionally, different kinds of chronicles, earlier studies and the webpages of the respective ski resorts were utilized. The secondary data were collected in each case by Master’s students, who also conducted some of the interviews and transcribed all the interview data. The sources of secondary data are presented in Table 35.3.

Table 35.3. Sources of secondary data.

| Levi | Ruka | Ylläs |

|

- Newspaper clippings obtained from the Kittilä library - Archives of Levin Matkailu Ltd - A chronicle of Levi - A chronicle of Levin Matkailukeskus Ltd |

- A chronicle of Ruka - Newspaper clippings from the local newspaper - Tourism strategy, statistics and master plan from the municipality of Kuusamo - Earlier research on Ruka development by Naturpolis Ltd |

- Newspaper clippings obtained from the local newspaper - A chronicle of Äkäslompolo village association - Archives of one municipality officer |

According to the interviewees, one of the key issues behind the success of Levi is the long-term plans upon which local development has been based. The municipality’s land use planning policy has been carefully thought out, facilitating start-ups and expansion of businesses. The main leader of the development projects has been a public utility in the municipality of Kittilä. Systematic construction of the close-knit Levi village centre was one of the key issues that allowed Levi to stand out from the competition. The local residents have had a decisive role when they selected for the municipal council people who wanted to develop tourism in Levi.

The mayor of Kittilä during the early years of the development of Levi was mentioned as integral in the early development of Levi. The success and the major role of the lift company is deemed to be based on its long-term managing director, who has been also a long-time chairperson of the board of directors of the Levi DMO. The interviewees believed that, since he was a local resident, he had a powerful motivation to turn both the lift company and the entire tourist destination into a successful business. The largest hotel, owned by the trade unions, also had a major role in the development of the Levi brand in the 1990s when it offered its services all year round, thus allowing the tourist destination to be open all year round. At present, there are several hotels and a large selection of other accommodation services in Levi, which has reduced the significance of individual actors.

The DMO has been handling joint marketing since 1987. The interviewees had strong faith in the ability of the DMO to plan and implement the marketing. According to the interviewees, systematic development of the Levi brand started when the DMO was established, and the organization’s success and significance are based on its long history. Literature often sees the management and development of a tourist destination as a process where the key responsibility is borne by a DMO (Pike and Page, 2014). The findings of the Levi case are partially congruent with this assumption. The board of directors of the DMO was compared by the interviewees to a team where each player has their own role and their own views about issues. This finding seems to indicate that, in the case of Levi, the managing director of the DMO does not carry the principal responsibility for the generation of the key elements; instead, the policies are determined by the board of directors. Cooperation between internal stakeholders is deemed an important issue in Levi, even though certain people have had a key role. The cooperation between the parties has created an atmosphere that encourages investments and construction and also attracts customers.

The interviewees did not share any clear idea about the Levi brand identity. Nevertheless, they stated that cooperation between the actors is important for the brand. Images of good location and accessibility, concrete versatility of services, cooperation within the area, active operations and being an industry pioneer are issues that have been linked to the Levi brand. Some of the interviewees were of the opinion that Levi’s image as a party place is genuine and describes Levi well, and has been created based on the Levi brand identity. Many of the interviewees were of the opinion that the image of Levi had been created by the joint marketing efforts and marketing plans, but some of the interviewees thought that the party image was created by a couple of individuals alone. They believe a dominant image as a party venue is harmful for the area and did not wish to promote it further in the marketing communication. The local entrepreneurs have participated in the changing of the image by expanding and redeveloping their services to, for instance, make Levi a more child-friendly tourist destination.

All of the interviewees in the case of Ruka listed as one of Ruka’s strengths the excellent, close-knit and persistent cooperation between the key entrepreneurs and business managers. The cooperation between the companies continued for decades without any official organization, shaping mutual trust. The Ruka-Kuusamo Tourism Association was established as late as 2002 to continue the joint marketing. All of the interviewees were clearly of the opinion that people who are able to work together are the key to successful cooperation. According to them, the secret of a successful and growing destination lies in innovative and enthusiastic entrepreneurs and leaders as well as having someone who knows how to coordinate the activities. The interviewees mention three key entrepreneurs that can be seen as drivers of development in Ruka.

The roles of entrepreneurs, municipal officials and politicians have changed in the course of Ruka’s life cycle. The role of the municipality was especially important in the early 1980s when land use plans that would remodel the entire area were made in Ruka. The interviewees also note that in the 1980s and right up to 1997, the mayor of the municipality was the personage who exerted marked influence on the development of tourism, together with the key entrepreneurs. Favourable attitudes of the municipal decision makers and comprehensive networks consisting of decision makers in the Helsinki Metropolitan Region were also needed.1

The Ylläs area is geographically divided into two separate villages on opposite sides of Ylläs, which creates a unique local setting to the destination. According to the interviewees from Ylläs, as well as some of the interviewees from Ruka and Levi, this setting has affected the development of the area significantly. Three of the interviewees from Ylläs regard it as a strength, while others consider the setting to have caused fragmentation in the cooperation and overall development of the area throughout the years. The situation has created a competitive setting between the villages, which, again, has affected their ability to cooperate well and make decisions together. The situation has also created a setting in which locals identify themselves with their own village rather than identifying themselves with Ylläs. This brings challenges to effective cooperation and leadership. On the positive side, the new road between the villages (opened in 2005), shortening the distance from 31 km to 15 km, was believed to have diminished the competition between the villages and brought them a little closer to each other.

The local setting of being divided into two villages also surfaces from how the destination marketing and cooperation have developed in Ylläs. Creating a joint marketing organization and conducting effective cooperation have been challenging in the area. There has been no collective vision among destination stakeholders. The marketing organization has tried to placate the desires and interests of all of its members, causing the effectiveness of marketing practises to suffer and the development to become slower. This has also had a negative effect on trust among stakeholders. Trying to please everyone has led to a situation where there is no focus on who should be the target customers. Over the years, there has also been a dichotomy between cross-country and downhill skiing, causing fragmentation in the marketing practises. However, nature as the focus of marketing has nowadays gained consensus among the stakeholders.

The municipality’s role in the joint marketing and cooperation has been insignificant in the past. The interviewees had consistent views on how the municipality has related to tourism in the Ylläs area in the past. Instead of tourism, the focus has rather been on the mining industry. The role of the municipality in the joint marketing of Ylläs has also so far been insignificant.

The findings of Ylläs suggest that the cooperation has not been working effectively, mainly due to disagreements among entrepreneurs, lack of collective vision and trust, and difficulties in committing to joint efforts. The DMO has been to some extent ineffective in its operations and the municipality has not been supporting tourism development. No definitive leader is present in guiding the cooperation and the local tourism entrepreneurs or other tourism actors are not keen to attain this position. The Ylläs area is considered to lack strong tourism personalities that would lead the destination cooperation and development of the entire area.

The comparison of the three cases is summarized in Table 35.4. When comparing the three cases, Ruka and Levi have had no political pressures preventing their focus on developing central villages in the resort, whereas Ylläs has had from the very beginning a unique setting, with the area being divided into two separate centres. This has over the years overemphasized the topic of local context and affected the way cooperation and leadership have formed in Ylläs. Though the interviewees of Levi and Ruka have emphasized the crucial role of the municipality in long-term planning, active land ownership and land use policy, the municipality of Kolari has not had this kind of role. This may be due to the fact that the local setting causes political rivalry between the villages across all kinds of municipality policies and decision making. Hence, the strong role of the municipality particularly in the early stages of the development of the resorts, with the help of political support from the residents, has made it possible for Levi and Ruka to have favourable circumstances for growth and success.

In the early years of the development of Ruka and Levi their home municipalities had committed, visionary, charismatic and active mayors, and/or other municipality officers, who used their personal networks and charisma when negotiating with potential investors and other stakeholders in order to enhance the development of the resorts. Interviewees from both Levi and Ruka also emphasized the role of charismatic entrepreneurs and managers of the core companies as key success factors of the resorts. Their enthusiasm has encouraged new entrepreneurs to start new businesses and grow. In Ylläs resort, there seem to be some visible and strong personalities who often have opposing approaches to each other when trying to make decisions together. In Levi all the key personnel in the destination development mentioned by the interviewees were originally local people. This was also the case in Ruka, although the ‘father’ of Ruka originally came from the capital area of Finland.

Based on these three case studies, the core factor enhancing the success of the ski resorts seems to be successful collaboration between the private and public sector stakeholders and particularly between the entrepreneurs. The Ruka case is an example of a destination that succeeded in growing and developing even without a formal collaborative organization. On the other hand, Levi has had a well-functioning DMO from the early years of its success story. In Ylläs, two separate villages and disagreements among entrepreneurs, together with actors with strong opposing views, were regarded to be noteworthy factors causing difficulties in cooperating and conducting joint marketing decisions. Finally, collaboration requires leadership, and based on the findings of our three case studies, leadership seems to be based on charismatic, collaborative personalities, not on organizations.

There was one issue that was common for all cases, namely lack of consensus about the ski resort brand identity. In Levi and Ruka there was some disagreement between the stakeholders about the positioning of the resort in the market. Although the ‘party image’ seems to bring profits, particularly to restaurants, it may be harmful in the family segment. In Ylläs, the disagreements were about the contradiction between ski slopes and pure nature. Nevertheless, all the resorts have been able to find a consensus about the core message of the marketing communication.

This study suggests that effective collaboration and leadership are key facilitators to the success of a destination. The findings support the notion of Beritelli and Bieger (2014), who suggest that the leadership in a destination is attributed to individuals, not necessarily to organizations. As Komppula (2016) notes,

charismatic entrepreneurs and business managers, committed and visionary municipality officials and influential politicians may take control of leadership in the destination, being those individual people who are the primary stakeholders in tourism development.

(Komppula, 2016, p. 73)

This notion is also supported by Franch et al. (2010). Characteristics of charismatic entrepreneurs (McCarthy, 2003) are typical for these key actors: intuitive, visionary and creative.

It can be argued that a strong role of local people may be a strength for a destination, enhancing the sense of identity with the place and facilitating a cooperative atmosphere among the actors, supporting the findings of Hallak et al. (2012), Czernek (2013), Kennedy and Augustyn (2014), Kozak et al. (2014) and Åberg (2014). Being ‘local’ does not necessarily need to refer to being born in the region, or being a permanent resident of the region, but may also refer to a long-term commitment to the region in a form of business ownership and active presence in the daily operations, as is shown in the Ruka case (Komppula, 2016). Nevertheless, strong local identity in two separate villages in Ylläs has affected cooperation negatively throughout the years of joint marketing, confirming Komppula’s (2014) findings from a rural destination in Finland, which emphasize that geographical fragmentation can create a barrier to effective cooperation.

Community-type destinations, like all these ski resorts, are often built on networks in which a variety of stakeholders interact with each other and affect each other (Beritelli et al., 2007; Franch et al. 2010). This study shows that the leadership role of the DMO as a forum for collaboration for stakeholders may be fruitful, as in the case of Levi. On the other hand, in Ruka, the DMO was not seen as the leader of the collaboration. A DMO could take the role of creating a cooperative atmosphere and interacting with destination stakeholders (Bornhorst et al., 2010), which could be possible in the case of Ylläs, if it had an external manager, neutral to both villages, and capable of building trust among the stakeholders. Bornhorst et al. (2010) suggest that stakeholders can either provide coordination, increasing success, or cause fragmentation, which reduces success. According to them, this choice is important for every single stakeholder and is highly influenced by the leadership style of the DMO and the degree to which it is stakeholder-oriented.

Päivi Pahkamaa, MSc (University of Lapland), Miikka Pohjola, MSc, and his supervisor Saila Saraniemi, PhD (University of Oulu), are gratefully acknowledged for their contribution in data collection and the initial phase of the data analysis in the cases of Levi and Ruka.

1For more detailed information about the Ruka case, see Komppula (2016) and Saraniemi and Komppula (2019).

Åberg, K.G. (2014) The importance of being local: prioritizing knowledge in recruitment for destination development. Tourism Review 69(3), 229–243. DOI:10.1108/TR-06-2013-0026

Beritelli, P. and Bieger, T. (2014) From destination governance to destination leadership – defining and exploring the significance with the help of a systemic perspective. Tourism Review 69(1), 25–46. DOI:10.1108/TR-07-2013-0043

Beritelli, P., Buffa, F. and Martini, U. (2015) The coordinating DMO or coordinators in the DMO? – an alternative perspective with the help of network analysis. Tourism Review 70(1), 24–42. DOI:10.1108/TR-04-2014-0018

Beritelli, P., Bieger, T. and Laesser, C. (2007) Destination governance: using corporate governance theories as a foundation for effective destination management. Journal of Travel Research 46(1), 96–107. DOI:10.1177/0047287507302385

Bornhorst, T., Ritchie, B.J.R. and Sheehan, L. (2010) Determinants of tourism success for DMO’s and destinations: an empirical examination of stakeholders’ perspectives. Tourism Management 31(5), 572–589. DOI:10.1016/j.tourman.2009.06.008

Bregoli, I. and Del Chiappa, G. (2013) Coordinating relationships among destination stakeholders: evidence from Edinburgh (UK). Tourism Analysis 18(2), 145–155. DOI:10.3727/108354213X13645733247657

Czernek, K. (2013) Determinants of cooperation in a tourist region. Annals of Tourism Research 1(40), 83–104. DOI:10.1016/j.annals.2012.09.003

Eriksson, A. and Kovalainen, P. (2008) Qualitative Methods in Business Research. Sage, London.

Ferrand, A. and Vecciatini, D. (2002) The effect of service performance and ski resort image on skiers’ satisfaction. European Journal of Sport Science 2(2), 1–17. DOI:10.1080/17461390200072207

Finnish Ski Area Association (2014) SHKY Hiihto- ja laskettelututkimus 2014. TNS. Available at: www.ski.fi (accessed 18 May 2018).

Finnish Ski Area Association (2016) SHKY Laskettelijatutkimus – Toukokuu 2016. Available at: www.ski.fi (accessed 18 May 2018).

Finnish Ski Area Association (2018) Kaikki laskettelusta, lumilautailusta ja Suomen hiihtokeskuksista. Available at: www.ski.fi (accessed 18 May 2018).

Franch, M., Martini, U. and Buffa, F. (2010) Roles and opinions of primary and secondary stakeholders within community-type destinations. Tourism Review 65(4), 74–85. DOI:10.1108/16605371011093881

Godfrey, K.B. (1999) Attributes of destination choice: British skiing in Canada. Journal of Vacation Marketing 5(1), 225–234. DOI:10.1177%2F135676679900500103

Hallak, R., Assaker, G. and Lee, C. (2013) Tourism entrepreneurship performance: the effects of place identity, self-efficacy, and gender. Journal of Travel Research 54(1), 36–51. DOI:10.1177%2F0047287513513170

Hankinson, G. (2012) The measurement of brand orientation, its performance impact, and the role of leadership in the context of destination branding: an exploratory study. Journal of Marketing Management 28(7–8), 974–999. DOI:10.1080/0267257X.2011.565727

Kennedy, V. and Augustyn, M.M. (2014) Stakeholder power and engagement in an English seaside context: implications for destination leadership. Tourism Review 69(3), 187–201. DOI:10.1108/TR-06-2013-0030

Komppula, R. (2014) The role of individual entrepreneurs in the development of competitiveness for a rural tourism destination: a case study. Tourism Management 40, 361–371. DOI:10.1016/j.tourman.2013.07.007

Komppula, R. (2016) The role of different stakeholders in destination development. Tourism Review 71(1), 67–76. DOI:10.1108/TR-06-2015-0030

Komppula, R. and Laukkanen, T. (2016) Comparing perceived images with projected images – a case study on Finnish ski destinations. European Journal of Tourism Research 12, 41–53.

Konu, H., Laukkanen, T. and Komppula, R. (2011) Using ski destination criteria to segment Finnish ski resort customers. Tourism Management 32(5), 1096–1105. DOI:10.1016/j.tourman.2010.09.010

Kozak, M., Volgger, M. and Pechlaner, H. (2014) Destination leadership: leadership for territorial development. Tourism Review 69(3), 169–172. DOI:10.1108/TR-05-2014-0021

McCarthy, B. (2003) Strategy is personality-driven, strategy is crisis-driven: insights from entrepreneurial firms. Management Decision 41(4), 327–339. DOI:10.1108/00251740310468081

Metsähallitus (2018) Kansallispuistojen, valtion retkeilyalueiden ja muiden virkistyskäytöllisesti merkittävimpien Metsähallituksen hallinnoimien suojelualueiden ja retkeilykohteiden käyntimäärät vuonna 2017. Available at: www.metsa.fi/documents/10739/3335805/kayntimaarat2017.pdf/d4414a36-b10d-428c-aa90-c5b50f25e4e5 (accessed 8 June 2018).

Pechlaner, H., Kozak, M. and Volgger, M. (2014) Destination leadership: a new paradigm for tourist destinations? Tourism Review 69(1), 1–9. DOI:10.1108/TR-09-2013-0053

Pforr, C., Pechlaner, H., Volgger, M. and Thompson, G. (2014) Overcoming the limits to change and adapting to future challenges: governing the transformation of destination networks in Western Australia. Journal of Travel Research 53(6), 760–777. DOI:10.1177/0047287514538837

Pike, S. and Paige, S.J. (2014) Destination marketing organizations and destination marketing: a narrative analysis of the literature. Tourism Management 41(1), 202–227. DOI:10.1016/j. tourman.2013.09.009

Presenza, A. and Cipollina, M. (2010) Analysing tourism stakeholder networks. Tourism Review 65(4), 17–30. DOI:10.1108/16605371011093845

Richards, G. (1996) Skilled consumption and UK ski holidays. Tourism Management 17(1), 25–34. DOI:10.1016/0261-5177(96)00097-0

Russell, R. and Faulkner, B. (1999) Movers and shakers: chaos makers in tourism development. Tourism Management 20(4), 411–423. DOI:10.1016/S0261-5177(99)00014-X

Russell, R. and Faulkner, B. (2004) Entrepreneurship, chaos and the tourism area lifecycle. Annals of Tourism Research 31(3), 556–579. DOI:10.1016/j.annals.2004.01.008

Saraniemi, S. and Komppula, R. (2019) The development of a destination brand identity: a story of stakeholder collaboration. Current Issues in Tourism 22(9), 1116–1132. DOI:10.1080/13683500.2017.1369496

Strobl, A. and Peters, M. (2013) Entrepreneurial reputation in destination networks. Annals of Tourism Research 40, 59–82. DOI:10.1016/j.annals.2012.08.005

Timur, S. and Getz, D. (2008) A network perspective on managing stakeholders for sustainable urban tourism. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management 20(4), 445–461. DOI:10.1108/09596110810873543

Tuohino, A. and Konu, H. (2014) Local stakeholders’ views about destination management: who are leading tourism development? Tourism Review 69(3), 202–215. DOI:10.1108/TR-06-2013-0033

Volgger, M. and Pechlaner, H. (2014) Requirements for destination management organizations in destination governance: understanding DMO success. Tourism Management 41(1), 64–75. DOI:10.1016/j.tourman.2013.09.001

Zehrer, A., Raich, F., Siller, H. and Tschiderer, F. (2014) Leadership networks in destinations. Tourism Review 69(1), 59–73. DOI:10.1108/TR-06-2013-0037