Myanmar used to be a country that inspired hope. The long-ruling military junta helped set up an election in 2010 and relinquished power to a civilian government the following year. Social media use soared as people in the country clamored to exercise newfound freedoms.1 Facebook became the primary platform for public life and, in short order, an infrastructure for spreading hate speech and religious anger. A viral campaign against the Rohinga ethnic minority turned political rhetoric into violence and a complex humanitarian disaster.2 Social media went from being the platform for community in a young democracy to a coordinating mechanism for genocide. Not only have tough regimes adopted social media, but they learn from each other. Myanmar’s trolls got their training in Russia.3

The Russian government’s spin machine also provides a good example of how big political lies get produced. The social media algorithms that Google, Facebook, Twitter—and even dating apps—use are examples of the computational systems that distribute big political lies. And firms such as Imitacja Consulting and Imitação Services illustrate how big political lies get marketed. When all the components of a lie machine work in harmony, the complete system of producing, distributing, and marketing political lies can have a significant impact on the course of current events, public understanding of crucial issues, and international affairs.

Lobbyists, political campaign managers, and politicians use social media to communicate directly with their constituents or the public at large. Tools like Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook allow campaigners to communicate without worrying about how journalists and editors may change, interpret, or fact-check the campaign messages. But editors and journalists provide a critical independent source of public knowledge and play an important role in evaluating the performance of elected leaders and public policy options. They check the claims of candidates who are running for election, and when political parties advertise, journalists do the fact-checking to investigate which political claims are most accurate. Removing professional editors and journalists from the flow of political news and information means that there are fewer checks on the quality of opinion and facts that circulate in public conversation.

But how do we know that communicating directly with voters—cutting professional news organizations out of the process—actually works? Social media firms themselves insist that fake news is only a tiny fraction of the content their users share and that they can’t influence political outcomes.4 (Though firms also insist to advertisers that ad campaigns purchased on their platforms have measurable influence!) Survey research estimates that the average US adult read and remembered at least one fake news article during the 2016 election period, with higher exposure to pro-Trump articles than pro-Clinton articles.5 But the researchers found it tough to estimate the impact of the fake news articles they studied on voting patterns. Exposing voters to one additional television campaign ad raised vote share by 0.02 percent, according to one model, so if one fake news story had the same influence as one television ad, the overall impact of fake news on the vote would have been tiny.6 Of course, these aggregated, national-level models for how modern lie machines work always miss the point of running a misinformation campaign on social media. Average effects across an entire country are not what modern lie machines are designed to create. It is network-specific effects, sited in particular electoral districts, among subpopulations, that are sought. The ideal outcome for political combatants is not a massive swing in the popular vote but small changes in sensitive neighborhoods, diminished trust in democracy and elections, voter suppression, and long-term political polarization.

Research finds that the good political ads really can motivate voters during a campaign. When political images are used to make emotional appeals and cue up enthusiasm, we respond by being motivated to participate and react with our existing loyalties. When such appeals are designed to stimulate fear, we can also be activated but are more likely to rely on in-the-moment thinking and be persuaded of new things.7 Using social media also has a positive impact on a politician’s share of the vote. Interestingly, the positive effect occurs when candidates for office push out lots of messages and broadcast their ideas. Interacting with voters on social media doesn’t seem to drive up vote share.8 Conversely, there is little consensus among researchers about the impact going negative has on voters. Some researchers argue that the impact is small, especially when staying positive can attract even more voters.9 Others argue that the effects of going negative can be especially potent for voters who are rarely engaged and not used to seeing political debate.10

Politicians always attack each other—obviously—and going negative, using manipulative rhetoric, or being aggressive in public debate doesn’t have to involve propaganda and political lies. Moreover, most of the research on negative campaigning involves large samples of voters and exposure to broadcast media, and the effects of concentrated social network messaging will be greatly intensified for some voters and some communities. So the next important step in understanding the political economy of lie machines is to trace the complete process, from production to dissemination to marketing, and see how the money flows, how the political lies appeal, and how voters respond.

Political campaigns generally attract supporters by using as much personal data as possible to tailor and customize political messaging, whether those campaigns are chasing the support of constituents, voters, members, consumers, or any other group of people. Sometimes this data is used for what is called political redlining, which is itself a core process for managing citizens.11

Political redlining restricts our future supply of civic information by relying on assumptions about our demographics and present or past opinions. Redlining can occur in several ways. First, political consultants can delimit which population is less likely to vote and design a campaign strategy with only likely voters in mind. Second, redlining can occur when a campaign manager decides to filter political information—or pass along misinformation—to users who have signed up for specific content. Third, redlining can be self-induced when individual users privilege some information sources over others or set topical preferences that prevent their exposure to undesirable sources or topics. Political communication experts have long used the internet to sequester their supporters. From the point of view of campaign managers, political redlining is reasonable because politicians want to secure their base of supporters.12

Redlining allows political campaign managers to segment populations and perform a type of campaign triage. For example, if poor people from an ethnic minority rarely vote, or if they always vote for your opponent, it may not be worth spending time in their neighborhood trying to convince them to vote for you. If one city has consistently voted for one party for decades and there is no evidence that public sentiment is changing, why spend scarce campaign resources on advertising there?

Today’s computational propaganda is built using the demographers’ and statisticians’ toolkit. Advances in measuring and modeling public opinion allow a political consultant to do more than simply identify and ignore nonvoters and committed opponents. Consultants can test the messages that might anger nonvoters enough to get them to vote or turn one of your opponent’s voters into one of yours. A well-assembled lie machine builds in constant message testing, so that the most successful social media messages on one day get even wider distribution the next. This is why well-produced junk news can outperform real news in global circulation over social media.13

But can we demonstrate how lie machines work? Can we discover what metrics are used in constructing a mechanism for manipulating public opinion? It’s probably impossible ever to model, without cooperation from Twitter, Facebook, or Google, how any particular post or search result changes a voter’s thinking. The firms themselves can model these things. A few years ago, their staff and contract researchers showed off how they can influence their users in some academic articles. But their poor ethical choices—coupled with the dramatic effects they revealed—attracted bad press, and their in-house researchers have since stopped writing about their findings.14

From outside the firms, researchers can set up highly controlled experiments to try and model the effects of junk news on voters, but the results of such research rarely reveal much about real-world settings. The outcomes would be so inorganic and unreal as to have little external validity because lab models would rarely extrapolate to real voters, real countries, or real elections. Instead, the gold standard in explanation in social settings is sensible causal narratives built through carefully organized evidence. As with any engine, taking the whole apart and reassembling the components helps us understand the mechanism. We will do just this to explain the impact and influence of one of the earliest, biggest lie machines to run in a democracy: the United Kingdom’s Brexit campaign.

Understanding how the modern political campaign works requires some knowledge of the data-mining industry, because this is the industry that supplies the information that campaign managers need to make strategic decisions about whom to target, where, when, with what message, and over which device and platform.15 Most citizens do not know how much information about them is held, bought, and sold by campaigns, advertising firms, political consultants, and social media platforms. Sometimes political campaigns have clear sponsors and declare their interests, but on other occasions such disclosures are hidden. Sometimes the public can see what kinds of advertisements are produced and distributed during a campaign season, but at other times the advertising is discrete and directed and not archived anywhere. Sometimes campaigns deliberately spread misinformation, lies, and rumors about rivals and opponents.

Raw data is an industry term for information that has not been processed or aggregated in some way. To make political inferences about someone, you usually need to take several kinds of data and put together an index that makes people more comparable to one another. For example, you could label someone a liberal if you acquire a list of their magazine purchases and find that they subscribe to a magazine where liberal commentators sometimes publish essays. But if you can find more raw data and learn that they are registered with a conservative party, that they have only ever voted for such a party, and that all their friends also vote for conservative politicians, you can make more precise inferences that this person should really be labeled a conservative. So the raw data about many of our behaviors, such as magazine purchases, party registration, voting history, and community ties, must be aggregated and weighed before reasonable political inferences can be made. And the person in this example would probably be scored as pretty conservative once all the relevant behaviors were evaluated.

Credit card data often helps kick-start such labeling exercises. Even though the transactions are between a buyer and a seller, credit card companies sell access to the transaction data to many third parties, including advertisers, public relations firms, and political consultants. Some third-party companies pay for access to the raw data, which they then must analyze themselves. Others prefer to pay for the finished analysis, so they will hire consultants like the now-defunct Cambridge Analytica to process the data and report on the important trends. The advantage of working with data brokers is that they can merge data sets from multiple sources and make even more powerful inferences.

Data mining has been an active industry for decades, so there are many kinds of aggregate categories available from data brokers.16 The difference that social media makes is that these services provide new kinds of data that allow more detailed insight into how particular people think and feel.

For example, a traditional political consultant might have compiled data on voting history and magazine purchases and be able to provide a list of who in a district is liberal and who is conservative. Today, a consultant working with social media and device data will also be able to pull out data about the websites that individuals in the district have been visiting in the last week and merge that with existing demographic data from the district. If a small network of social media users has suddenly started trading links that betray a shift in political perspective or an openness to reconsidering their opinion on some issue, the consultant could work out what new message would encourage such thinking and advise a campaign on whom to send it to. If the consultant can tell the campaign what groups of people may be changing their opinions, highly targeted messages can be sent to those groups through social media. If the consultant can map these personal attributes onto a list of names, physical addresses, or social media profiles, very personal messages can be sent to named individuals.

It is extremely difficult to keep track of who is using either personal records or aggregated data about individuals. There are a few online services that convert the complex legal terms of service agreements that social media companies provide into more accessible language. For example, the website “Terms of Service; Didn’t Read” will tell you how long social media services such as Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube hold on to data about your browsing history, or if they have no clear policy on that.17 Terms of service agreements do not usually identify which specific third-party organizations are making use of your personal records.

Much of what we know about the qualities and quantities of both raw and aggregated data comes from the negative publicity around data breaches, court cases, and government inquiries. When a credit card company or consulting firm gets hacked and personally identifiable information is compromised, we can see the vast range of variables that are collected about people. For example, in October 2017, the large credit card company Equifax experienced a data breach that involved nearly 143 million customers in the United States and United Kingdom, and exposed email addresses, passwords, driving license numbers, phone numbers, and partial credit card details. In 2018, several massive hotel chains revealed that similar details on half a billion customers had been breached.18 Political consultants are rarely caught working with hackers to steal data or interfere with the information infrastructure of another campaign. Usually they simply pay for voter intelligence from other firms that have legally bought access to raw and core data.

My own research into incidents of compromised records demonstrates that most so-called leakage is the result of corporate malfeasance.19 Malicious hackers or foreign governments are not the ones who expose the most records. Rather, personal records are more likely to be compromised by dissatisfied employees or loose security guidelines. Typically, breach incidents involve organizational mismanagement: personally identifiable information accidentally placed online, missing equipment, lost backup files, and other administrative errors.

Sometimes people ask to see what data credit card companies or consulting firms keep on them. But companies usually share only the most obvious and least controversial variables and consider the rest to be their corporate intellectual property.

Consulting firms that work with political candidates, political parties, and lobbyists are reluctant to talk about what data they have and where they obtained it. Most people, most of the time, are shocked when they realize how much information such data brokers have. But because the data is politically sensitive, such firms tend to work with affinity groups where trust runs high. One consulting firm will develop a reputation for taking on liberal politicians and working on liberal issues, and another will gain a reputation for taking on conservative politicians and working on conservative issues. Because it takes significant work to merge data and make political inferences—this aggregated information becomes the intellectual property of the firm—most consulting firms will not reveal their information sources. They will usually tell clients only about big picture trends and aggregate findings, and they are unlikely to deliver any raw data.

In fact, both the firms that generate raw data and the consulting firms that aggregate it will stick to the letter of the law on privacy and data mining. By and large they interpret their obligations to customers very narrowly. If they can do some things with data in some jurisdictions but not others, it is common that they will strategically move data into the more permissive jurisdictions. If challenged by a customer, firms find it easier to rewrite a terms of service agreement and call an unethical practice a condition of service rather than consider some higher ethical or legal obligations to protect privacy or democracy.

Large numbers of voters in elections and referenda decide how they will vote in the final days of campaigns. One public opinion study of several years of voter decision making and voter psychology found that in every modern election, between 20 percent and 30 percent of voters either made up or changed their minds within a week of the vote. Half of those individuals did so on election day itself. This proportion can be higher in a referendum, where people tend to think that their vote is more significant. This appears to have been the case in the United Kingdom’s 2016 referendum on leaving the European Union; one of the researchers’ key findings was that 54 percent of respondents perceived the EU referendum as the most important vote in a generation, with 81 percent considering it to be among the top three.20

The Vote Leave campaign had an aggressive social media strategy that included not only spreading misinformation about the costs and benefits of EU membership but also overspending on its social media campaign. The misinformation strategy was identified during the campaign, but the overspending was not ruled illegal until months after the outcome had been decided. Fortunately, there are enough publicly available sources to present a picture of the campaign’s strategy on producing, distributing, and marketing politically potent lies.

Three critical resources provide insight into how a lie machine such as the one run by Vote Leave can have an impact. The first is All Out War: The Full Story of How Brexit Sank Britain’s Political Class, by the investigative journalist Tim Shipman. Though Shipman is not focused on analyzing the use of social media, his interviews of people with firsthand campaign knowledge reveal much about the digital strategy of Vote Leave. The second is a detailed account of Vote Leave’s digital strategy by campaign director Dominic Cummings on his personal blog, https://dominiccummings.com. The third source is the UK House of Commons Digital Culture, Media and Sport Committee’s investigative findings on disinformation and fake news after the referendum result. Disinformation and “Fake News”: Interim Report, published in July 2018, contains information that Facebook furnished the committee concerning advertising on its platform by both Vote Leave and another group, BeLeave, during the campaign.

Like many national-level, high-stakes political campaigns in modern democracies, Vote Leave’s digital strategy was ambitious and involved a global network of contractors and consultants. The campaign was largely conducted by the Canadian firm Aggregate IQ (AIQ). The firm began by building a “core audience” for Vote Leave’s advertisements by first identifying the social media profiles of those who had already liked Eurosceptic pages on Facebook. Vote Leave advertised to this core audience to try and bring them onto its website, where they would be invited to add their personal details to its database. Another advertising tool within Facebook that AIQ used is called the Lookalike Audience Builder, which takes what is known about a group to help identify others for whom there might be some elective affinity.

This larger group, which AIQ designated the “persuadables,” consisted of Facebook users with the same demographic features as the known, core audience of Eurosceptics. However, these persuadables had not previously expressed interest in Eurosceptic content on Facebook by “liking” Eurosceptic pages. This group of persuadables reportedly contained “a number of better-educated and better-off people.” Cummings states in one of his blog posts that the persuadables were “a group of about 9 million people defined as: between 35–55, outside London and Scotland, excluding UKIP supporters and associated characteristics, and some other criteria.”21

Vote Leave then began a process called onboarding in the industry, whereby sympathizers were turned into committed supporters of, donors to, and volunteers for the campaign. To do this, Vote Leave and AIQ deployed advertising targeting the persuadables and employed a three-step process. The first step was to invite the reader to click on an online advertisement, displayed on Facebook or other digital channels, so they could be taken to Vote Leave’s website. Once the reader was there, the second step was to invite him or her to provide personal details—information that would also populate Vote Leave’s database. The final step was to invite the reader to donate, share Vote Leave’s messages, or volunteer for the campaign. Having social media users volunteer to communicate for the campaign was especially valuable because it generated additional organic growth in impressions without any cost to Vote Leave.

At each step in the onboarding process, the advertisements and messages were tested on an iterative basis. Ads or messages that failed to convince enough users to take the next step were reworked or changed entirely until a success threshold was reached. This threshold is known as the conversion rate, which I describe below. In his book, Shipman cites an anonymous source who described how Cummings evaluated each ad: “[He] approached each ad as if it were its own unique poll or focus group, and would compare those results to what they had observed from the data they had already been gathering. He was seeing what was being said in the polling and focus groups, and wanted to test those assumptions online to see that everything was in agreement with everything else. And when there were things which weren’t, [Vote Leave would] exploit them or retool.” Different ads were developed for the core and persuadable audiences. Core readers were served more demonstrative advertisements, whereas the persuadables reacted better to ads that appealed to their curiosity in weighing the arguments. “Is this a good idea?” and “Do you want to know more?” are cited by Shipman as typical messages.22

In May 2016, approximately four weeks before the referendum polling day, Vote Leave launched a competition to gather voters for its database. The competition promised a £50 million prize to anyone who could correctly predict the winner of all fifty-one games at Euro 2016, the soccer tournament. The purpose was to attract people who did not normally follow politics. Participants were asked to provide their name, mobile telephone number, address, and email details during the entry process. This data was fed into Vote Leave’s database. More than 120,000 people entered the competition, and each of them received a reminder on June 23, 2016, to vote in the referendum.

Vote Leave also launched an app for smartphones. This app gamified the process of learning about Vote Leave’s talking points, sending text messages to friends, watching Vote Leave’s video material, and similar actions. On June 23, 2016, people reportedly sent seventy thousand messages via the app reminding their friends to vote.

Vote Leave’s focus groups revealed how confused and fungible some voters were, changing their mind in response to whatever campaign ad they had seen most recently. So Dominic Cummings designed a “Waterloo Strategy” to deliver a huge barrage of Vote Leave advertisements to swing voters as close to the referendum as possible. An unidentified source from Vote Leave described the Waterloo Strategy: “Basically spend a shitload of money right at the end. We tested over 450 different types of Facebook ad to see which were most effective. We spent £1.5 million in the last week on Facebook ads, digital ads and videos. We knew exactly which ones were the most effective.”23

In Shipman’s account, Cummings is quoted as saying, “We ran loads and loads of experiments for months, but on relatively trivial amounts of money. And then we basically splurged all the money in the last four weeks and particularly the last ten days.”24 Most political campaigns expend the bulk of their resources in the final days of the campaign. But social media algorithms allow for the constant testing and refinement of campaign messages, so that the most advanced techniques of behavioral science can sharpen the message in time for those strategically crucial final days.

In his blog, Cummings writes, “One of the few reliable things we know about advertising amid the all-pervasive charlatanry is that, unsurprisingly, adverts are more effective the closer to the decision moment they hit the brain.”25

The Vote Leave campaign decided to focus on consistent and simple political lies: first, that the United Kingdom was spending £350 million a week on the European Union, which it could spend instead on the National Health Service if it left the European Union; second, that Turkey, Macedonia, Montenegro, Serbia, and Albania were about to join the European Union; and third, that immigration could not be reduced unless the United Kingdom left the European Union. The £350 million claim was declared inaccurate by several experts, including Sir Andrew Dilnot, the chair of the UK Statistics Authority.26 Similarly, the “Turkey claim” was untrue: there were no imminent plans for Turkey, Macedonia, Montenegro, Serbia, or Albania to join the European Union. So the first two were simply falsehoods—what we have since come to call “fake news.” The third claim was simply a vague, controversial assertion: there is no evidence that countries must leave the European Union to affect their immigration rates. Nevertheless, Vote Leave pressed on with all these messages throughout the campaign, especially in the final days, and there were dozens of ads with such messages.27

Every advertising campaign has what is called a conversion rate, and political campaigns are a form of advertising campaign. The conversion rate is the proportion of the audience that clicks on an online advertisement. Before social media existed, campaign managers simply bought banner ads, and they found that 1 percent of the people who see an ad will click on it, regardless of the topic. Of the people who do that in response to political messages, 10 percent will believe the message, and another 10 percent of those will be passionate enough about the topic to engage actively by buying the product, telling their friends about it, or participating in some other way.28

These days, campaign managers don’t need to purchase and place banner ads because platforms like Facebook can serve up a purposefully selected sample of impressionable users. Because the social media firms can use their internal analytics to presort users, online political advertising goes directly to the people who are persuadable. Effectively, this compresses the process that involves a scattershot strategy of general banner ads. That is, Facebook users who see a political advertisement have already been preselected for being sympathetic, based on some prior analysis of data about them. Conservatively, we can estimate that 10 percent of those preselected users will click through to the website and believe the messages they read on the website to be true. A further 10 percent can then be expected to do something over and above believing the message: actively protesting, donating, or getting engaged in some other way.29

Shipman states in All Out War that Vote Leave was aiming for a 30 percent conversion rate from its advertisements and a 50 percent conversion rate from the messaging that the audience would receive on its website’s landing pages. We don’t know if they achieved these results, but constant A/B testing would help them achieve high conversion rates. That is, by randomly serving social media users two versions of an ad that differs only in one element—the choice of image or turn of phrase—ad designers can compare the conversion rates of each message. This gives a political communication expert even better information about how to refine and target future ads.

Shipman argues that Vote Leave was able to achieve these target conversion rates by regularly evaluating the advertisements’ and political messaging’s effects. If so, then Vote Leave was able to achieve an even higher conversion rate than 10 percent. This would mean that if, say, an ad had a reach of ten thousand people, Vote Leave could then expect three thousand viewers to click through the ad to arrive at its website, where it could expect fifteen hundred of those people to provide their personal data and get engaged with the campaign. However, the real conversion rate for Vote Leave’s third step—getting someone to do something—is known only by Facebook and the other social media platforms where ads were placed. For the purpose of modeling the impact of directed political misinformation, let’s proceed with the more conservative assumptions about what conversion rates may have been achieved.

It certainly helped that Vote Leave and BeLeave spent more than they were legally allowed. It is impossible to make a counterfactual judgement with certainty—spending the budget they were allowed might still have produced the same political outcome. Nevertheless, it is possible to estimate how many additional people the campaign reached, and converted, with the extra funding these campaigns used. And doing so reveals that the outcome of the referendum could have been affected, based on what we know about the Vote Leave campaign’s impact and influence.

The UK Electoral Commission found in its report of July 17, 2018, that both Vote Leave and BeLeave breached campaign finance law: Vote Leave spent £449,079 in excess of the statutory limit, and BeLeave knowingly spent £666,016 more than the legal limit. The commission decided that both organizations had coordinated their campaigns and operated under a common plan of action, and fined both.30 These spending offenses seem independent of each other because the funds came from different bank accounts. But it is very common for affinity campaigns with a shared agenda to develop the same spending and communications strategies. Effectively, the money used by both BeLeave and Vote Leave advanced the same campaign.

To determine whether these extra resources affected the referendum outcome, we need to compare Vote Leave’s actual campaign with the campaign it would likely have run with the legal—but smaller—budget. Most of this excess spending would have gone to social media advertising. So, what kind of impact and influence might £449,079 in advertising have had, and could this have given Vote Leave the edge needed to win?

One way to answer this is by illustrating how Vote Leave’s campaign would have been affected if it had spent £449,079 less than it did. As I have said, Vote Leave put great emphasis on the last five days of the campaign, as part of the Waterloo Strategy. This strategy is detailed in Dominic Cummings’s blog post of January 30, 2017, “On the Referendum #22: Some Basic Numbers for the Vote Leave Campaign,” in which Cummings provides helpful charts.

The strategist reveals four digital advertising methods: video, search, display, and Facebook. Advertising on Facebook appears to be the largest part of the net spending. The campaign had a particularly successful run in its last few days of social media advertising. Facebook measures impressions to track the effectiveness of its advertising system. These are simply the total number of times an ad or post is displayed on a user’s screen. In total, Vote Leave ads had 891 million Facebook impressions, with more than 30 million impressions per day in the last few days of the campaign. The campaign’s video content was viewed by twenty-six million users—for at least ten seconds—with the highest viewing rates in the final days.

With such detailed information on how many people saw which kinds of advertising and how much that advertising cost, it is possible to model how much impact the excess campaign expenditures may have had on voters. In other words, Vote Leave spent £449,079 more than allowed by law, and we can estimate how many people the campaign reached with those resources. Since the charts report on the amounts paid in US dollars to US social media platforms, it makes sense to think this through in US dollars—at the time, this amount converted to $664,412.31

For a start, we could assume that these resources were all spent on all four types of digital advertising. This $664,412 would have covered the whole of Vote Leave’s digital strategy for the last two days of the campaign, which the campaign said cost $525,000. Had they respected the spending rules, Vote Leave would have had to stop all its digital advertising sometime during the afternoon of Tuesday, June 21, 2016.

Because the vast majority of campaign spending was on Facebook advertising, it makes more sense to estimate how many days of Facebook campaigning this $664,412 would have bought. If Vote Leave had respected the referendum spending limits, the campaign would have had to give up ten days of Facebook advertising. Knowing how much the campaign was spending each day allows us to count backwards from voting day, June 23. The organization’s spending in the last ten days adds up to just under the $664,412. If all other spending remained constant, forgoing $664,412 of Facebook spending would have meant that Vote Leave’s Facebook ads would have ceased on Monday, June 13, 2016, ten days before the referendum vote.

Cummings stated in his blog that between June 7 and June 19 the campaign was achieving around 15 million impressions daily. These success rates rose over time, and over the last days the impressions topped 25 million, then 30 million, then 40 million, and ultimately 45 million, according to the campaign managers. Putting this together with Cummings’s calculations, the excessive spending would have brought the campaign just under 24 million extra impressions each day for the final ten days of campaigning.

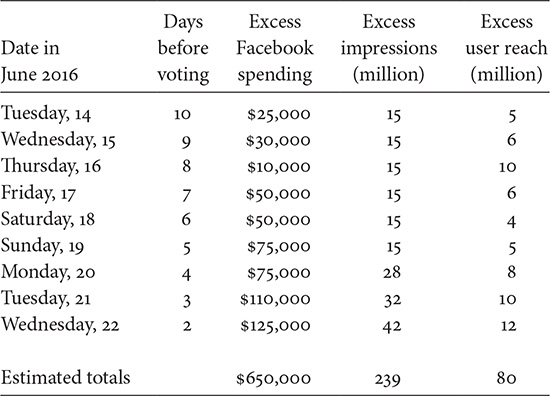

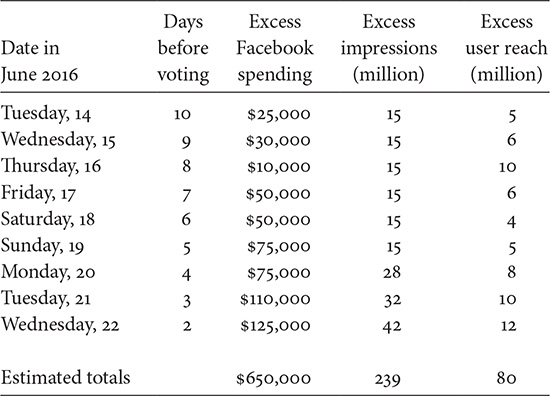

Conservative assumptions reveal that excess spending on social media advertising very likely resulted in 239 million extra impressions of Facebook ads (see table). If we take the low end of the campaign’s stated conversion rates, then 30 percent, or almost 80 million impressions, would have been clicked on by real users whom Facebook recommended as persuadable. Of those, at least eight million people would very likely have been persuaded by the messaging, and around eight hundred thousand people would very likely have been energized enough to donate time or money to the campaign.

Illustrative model of the impact of excessive spending on social media advertising

Source: Author’s calculations based on data available from multiple sources (Cummings, “On the Referendum #22”).

Note: The campaign spent $664,412 more than allowed by law; for the purpose of being conservative and for ease of calculation, this is rounded down to $650,000 and distributed equally over the final 10 days. In total this probably yielded 239 million impressions, or roughly 24 million impressions per day. But these impressions would probably have been distributed unevenly, with higher daily rates on weekdays and at the climax of the campaign. At its peak, the campaign may have been converting half of its user impressions into supporters, but this illustrative model makes a more conservative assumption that one in three of these persuadable users would have been converted.

Vote Leave’s social media advertisements would have reached millions of voters, but these ads were only one part of the overall leave campaign. Modern social media campaigning is often coordinated among affinity groups. Much of the overspending by Vote Leave was spent by BeLeave, which was equally effective. This is unsurprising given that BeLeave was also run by AIQ. Indeed, Vote Leave and BeLeave were affinity campaigns, meaning that their resources were spent with the same purpose. The Electoral Commission found, in its July 2018 report, that Vote Leave and BeLeave shared a common plan and that they both relied on AIQ’s services. The commission reported:

BeLeave’s ability to procure services from Aggregate IQ only resulted from the actions of Vote Leave, in providing those donations and arranging a separate donor for BeLeave. While BeLeave may have contributed its own design style and input, the services provided by Aggregate IQ to BeLeave used Vote Leave messaging, at the behest of BeLeave’s campaign director. It also appears to have had the benefit of Vote Leave data and/or data it obtained via online resources set up and provided to it by Vote Leave to target and distribute its campaign material. This is shown by evidence from Facebook that Aggregate IQ used identical target lists for Vote Leave and BeLeave ads, although the BeLeave ads were not run.32

The common messaging is evident in the choice of Facebook advertisements. BeLeave used some of the same kinds of misleading messages promoted by Vote Leave. For example, BeLeave wrote that “60 percent of our laws are made by from [sic] unelected foreign officials” (ad number 1430), and “We send £350m to the EU every week. Let’s spend it on our priorities instead” (ad number 155).33

In other words, BeLeave replicated the big lies crafted by the Vote Leave campaign, and in particular the £350 million claim. We can also model the impact BeLeave had using other kinds of data about that organization’s portion of the campaign strategy. All in all, Vote Leave paid £675,315 to AIQ, through BeLeave, for their common strategic campaign.34

The data released by Facebook to the Electoral Commission shows that BeLeave embarked on a Facebook advertising campaign on June 15, 2016, a day after the first transfer of some of these excess financial resources. Copies of these ads are now public because Rebecca Stimson, UK head of public policy at Facebook, provided them to the House of Commons Digital Culture, Media and Sports Committee in response to a question.35 In addition to providing the images and videos used in the advertisements themselves, Facebook revealed how well the different ads performed and broke down ad impressions by gender and region. This information not only allows for some modeling of the campaign but also reveals how some of Facebook’s microtargeting options are used by campaign managers.

According to Facebook, BeLeave bought 120 advertisements and started running them on June 15, 2016—the day after Vote Leave and BeLeave paid AIQ for their campaign strategy. For the most part, once an ad started to run, it was not discontinued entirely. Of the 120 ads, only 2 ended their run before voting day. In the public information we have about this part of the campaign, the number of impressions each ad achieved—that is, the number of times it was displayed to Facebook users, regardless of whether they had already seen it or other advertisements from BeLeave—is given in ranges. Some ads garnered under a thousand impressions, whereas the successful ads produced five to ten million impressions.

By combining the lower and upper limits of the impression ranges for each ad, it is possible to arrive at an overall lower and upper limit for all the ads that ran. In total, BeLeave’s ad campaign on Facebook resulted in between 47 and 105 million impressions.

In terms of reach, the Facebook records do not provide a total reach for each ad. The records do break down the reach for each ad group according to gender and age range, such as eighteen- to twenty-four-year-olds, as a percentage. For example, of one ad group’s total reach, 10 percent went to females between the ages of twenty-five and thirty-four. Reach data is also provided by region and includes both views by targeted users and views by friends and family who received the ads because of sharing patterns within their network. The reach data suggests that, initially, BeLeave may have been targeting its ads at people between the ages of eighteen and forty-four, without any discernible gender bias. However, later groups of ads do not appear to show age bias. The audience for these ads was in England, and only a few Facebook users in Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland were targeted. In this way, Facebook’s preselection process was consistent with what pollsters were saying about the limited appeal of Brexit to voters in those regions.

It appears from Facebook’s spreadsheet that BeLeave’s net return on its spending of £666,016 was not as successful as the other campaign, but it still reached millions of people. BeLeave garnered between 47 and 105 million impressions over eight days. Following the same conservative assumptions about conversion used above, we can estimate that between 4.7 and 10.5 million voters would have seen these ads and been persuaded, and between 470,000 and 1 million voters would have been energized enough to donate money or time to the campaign. Importantly, Northern Ireland’s Democratic Unionist Party and a group called Veterans for Britain were other affinity campaigns contributing to these ad networks in various ways.

Working on the other side of this referendum question was the Remain campaign, which spent its resources in a legal way and ended its digital advertisements on the day before voting. Campaign managers normally try to control spending to save resources for the final push. This would be consistent with best practices in political campaigning: you keep track of your legally allowed campaign budgets and time the purchase of ads so that the climax in ad spending coincides with the climax of the campaign period—right to the final hours—in which you are legally allowed to campaign.

In the final days before voting, the Vote Leave campaign’s political redlining of UK voters would have been most effective. Recall that between 20 percent and 30 percent of voters make up or change their minds within a week of the vote and that half of those individuals do so on election day itself. Vote Leave’s campaign engineer Dominic Cummings noted that “something odd happened on the last day, spending reduced but impressions rose by many millions so our cost per impression fell to a third of the cost on 22/6 which is not what one would expect and we never bothered going back to Facebook to ask what happened.”36 The early end to Remain’s advertising had two consequences. On the last day of voting, only the Brexit campaign’s messages would have been going out to the 10 to 15 percent of voters who had not decided how to vote. Simultaneously, the lack of competition would have caused the cost of each advertisement to drop. Facebook’s advertising prices are determined through an automated auctioning system, and prices are based on the competition between advertisers seeking the same or overlapping audiences. With the Remain campaign no longer bidding, the Brexit campaign’s illegal ad budgets would have gone much further in those final hours.

Measuring the impact of how political information is presented over social media is tough. The social media firms don’t admit much about how they can affect people when it comes to political opinion, though they certainly claim much about how they can affect people when it comes to consumer behavior. In one small study of voter turnout run by Facebook itself on its own users, one single tweak in platform design caused 340,000 more voters to vote on election day.37

It is important to remember that rich data on voters doesn’t just feed the complex learning algorithms of the social media firms. An important part of the mechanism is offline, and such data feeds the apps that advise campaign workers on whom to visit during the campaign period and with what message. Both Brexit and Trump campaign canvassers used apps that could identify the political views and personality types of a home’s inhabitants, allowing canvassers to ring only at the doors of houses that the app rated as receptive. Canvassers had scripts tailored to the personality types of residents and could feed reactions back into the app; that data then flowed back to campaign managers to refine overall strategy.38

In the end, the result of the 2016 EU referendum in the United Kingdom was that 48 percent of voters preferred to remain and 52 percent of voters preferred to leave. The Brexit campaign won by just over 1.2 million votes. A swing of about 600,000 people would have been enough to secure victory for Remain. Almost 80 million extra Facebook ads would have been served up to persuadable UK voters during the period of excess spending. The Brexit campaign machine was aiming for a conversation rate of 50 percent. But even taking the more conservative industry conversion rate of 10 percent, at least 8 million people would not only have accepted the messaging but clicked through to Brexit campaign content in that sensitive moment. More than 800,000 of those Facebook users would have accepted and consumed the content, which included several lies, but also would have been energized enough to engage more deeply with campaign activities. It is very likely that the misinformation campaign reached millions of voters throughout the campaign period and that the excessive spending helped secure a political outcome in the referendum result.

I have made some conservative assumptions about measuring the effects. First, these Brexit communication campaigns were targeting likely voters and, in the final days, were running after the Remain campaign had reached the statutory spending cap and stopped advertising. Second, this conclusion is based on Vote Leave data alone—better data from the other affinity campaigns would allow for a more refined estimate of the overall impact. Still, we can conservatively say that Vote Leave and BeLeave would have reached tens of millions of people over the final days of the campaign, only because they spent more than legally allowed on a savvy digital advertising strategy. Third, Vote Leave’s dynamic, iterative ad-testing system would have achieved rising success rates over time. In this breakdown I have worked with a conservative 10 percent conversion rate rather than the 50 percent rate that campaign managers aspired to and may have, on occasion, achieved. Fourth, these findings are based only on Facebook advertising data. The supplementary video, search, and display strategies would have reached additional voters and hit the persuadable voters many times over. Last, the cost of Facebook advertising decreased on the day of the referendum itself, meaning that Vote Leave’s excess spending would have afforded even more impressions than estimated in this conservative model. Much of what political communication scholars know about voter influence is generated from models of how US voters learn. So it is possible that UK voters would have had different conversion rates. Since both countries are English-speaking, advanced democracies with similar media environments, the comparison is probably safe.

While these simple calculations illustrate how a social media campaign was organized to influence voters, many other factors could have affected the outcome. But with the available evidence on the spending and strategy of these campaigns, we can reconstruct the influence models that campaign managers themselves use to shape political outcomes. Moreover, this evidence allows us to illustrate how the many components of a complex lie machine—systems of production, distribution, and marketing, especially misinformation and social media algorithms—can together make an impression on millions of voters.

Many kinds of politically motivated lies are easy to catch under scrutiny, but it isn’t always possible to get people to stop believing them. For philosophers, a lie involves telling people something you believe to be false with the intention that they believe what you say. Unfortunately, this understanding of what a lie is fails to capture many significant forms of deceptive behavior that we now see in complex political misinformation campaigns. The Brexit campaign used misleading images as well as words in messages that sowed doubt and confusion. And platforms such as Facebook may not care what its users believe so long as the false stories generate advertising revenue. Lie machines are a significant threat to democracy because they give us the wrong information, or poor-quality information, that prevents us from making informed decisions on policy issues or on election day. Fortunately, we’ve deconstructed and dismantled the complex mechanism of producing, distributing, and marketing big political lies, so in the next chapter we’ll explore the best options for protecting democratic institutions. How do we save democracy?