High Rollers

On April 9, 2012, Jann Wenner and Eric Bates, the publisher and editor of Rolling Stone magazine, interviewed Barack Obama. It was, they could not help but note, the “longest and most substantive interview the president had granted in over a year.” Before the interview began, Wenner and Bates gave Obama a gift. Obama knew immediately what it was. The last time Wenner had interviewed him, Obama had commented on his flashy socks. This time Wenner came prepared, giving Obama two pairs, one “salmon with pink squares” and one with “black and pink stripes.” Obama liked them—“These are nice”—but then seemed to hesitate. “These may be second-term socks,” he said.1

Soon after this interview, Obama’s chances of wearing those socks seemed to be decreasing. On May 4, the Bureau of Labor Statistics reported the monthly jobs numbers. The New York Times’s headline referred to an “ebb in jobs growth” and the leading paragraph noted, “The nation’s employers are creating jobs at less than half the pace they were when this year began.” Although the unemployment rate ticked downward, from 8.2 to 8.1%, this was only because so many Americans had essentially dropped out of the labor force and stopped looking for work. In sum, the report was “disappointing” and unemployed workers were “pretty discouraged.”2

A month later, the news got even worse. The initial jobs report for May found that even fewer jobs had been created than in April, and the unemployment rate increased slightly, back to 8.2%. CBS News called the report “rotten,” and the Huffington Post quoted an economist saying, “This is horrible.”3 Obama acknowledged the challenges the country faced but promised improvement: “We will come back stronger. We do have better days ahead.” Meanwhile, Mitt Romney pounced, calling the jobs report “devastating news for American workers and American families” and saying “the Obama economy is crushing America’s middle class.”4 With the economy wobbly and the presidential campaign beginning in earnest, the summer of 2012 seemed like it could provide a real turning point in the race—perhaps even vaulting Romney into the lead.

This was not to be. Obama had the lead as Romney clinched the nomination, and Obama would retain that lead as the party conventions were set to begin in late August. In many respects, his lead was predictable. Even with the wobbly economy, Obama was still forecast to win. The lead he retained throughout the summer was one he should have had based on economic conditions alone. Moreover, many voters were reliably partisan and did not appear to change their minds during this time. Partisanship rendered them immune from the events that captivated political observers during the summer of 2012, such as Obama’s advertising blitz and the string of “gaffes” committed by Obama and Romney. A small number of potentially persuadable voters may have responded to these events, but our data suggest that for most voters—more than 90%—their initial choice seemed like the right one.

The stability was also a direct consequence of the campaign itself. Stability is typically a feature of the competitive environment of presidential campaigns. Unlike candidates in many down-ballot races, the major-party presidential nominees are usually evenly matched. They tend to have roughly equivalent resources: lots of money, professional campaign organizations, and so on. In short, they are good at competing, most of the time, and this means their efforts neutralize each other, even though thousands of advertisements are being aired and tens of thousands of doors are being knocked on. In a tug-of-war, the flag in the middle of the rope does not move if both sides pull with equal force—even though both sides are pulling hard.

This is much different than the dynamic we described in the Republican presidential primary. There the candidates were not evenly matched. Some were well connected, well funded, and well prepared. Others were running campaigns out of their pickup trucks. Because voters were not familiar with many of them, new information gleaned from news coverage or electioneering could have a powerful effect—thus the cycle of discovery, scrutiny, and decline that we documented for Perry, Cain, Gingrich, and Santorum. In the general election, the effects of news coverage, campaign ads, and the like were much harder to see. Although the efforts of the candidates may have produced small shifts in the polls, in general the candidates were so evenly matched that their efforts canceled one another out.

A presidential general election campaign typically resembles a concept from the sciences called a “dynamic equilibrium.” In a dynamic equilibrium, things are happening, sometimes vigorously or rapidly, but they produce opposing reactions that are roughly the same size or magnitude and that occur at roughly the same rates. Thus, the entire “system”—populated by candidates, media, and voters—appears stable, or at a “steady state,” to use more scientific nomenclature, even though it is not static. Reams of news coverage and vigorous campaigning coincide with stable polls.

But the equilibrium can be thrown out of balance. If one candidate were not as good a campaigner, or adopted a poor strategy, or inexplicably decided to sit out the campaign, the polls would likely move toward the other candidate—just as the stronger team in a tug-of-war can move the flag tied to the rope. Lopsided campaigns can produce larger campaign effects. It is just that lopsided campaigns have been relatively rare in recent presidential general elections. This makes uncovering the effects of presidential campaigns challenging. Stability may actually be the result of two highly effective campaigns, not two dismally ineffective campaigns.

The summer of 2012 was interesting precisely because it seemed like it might disrupt the campaign’s equilibrium. Both candidates made big bets. Romney’s choice of Paul Ryan as a running mate seemed to signal a shift in Romney’s message from Obama’s handling of the economy to a debate about the size of government and the national debt. The Obama campaign bought a lot of advertising unusually early in the general election campaign, attacking Romney even before he officially had the nomination.

But neither of these gambits amounted to much—at least in terms of votes. Over the summer months, Obama and Romney fought hard, but largely fought to a draw. Voters were ambivalent enough about issues surrounding the economy and the size of government that neither candidate could clearly win the argument. Moreover, Obama’s early advertising advantage produced at best a short-lived boost. And though both candidates had good and bad news cycles—thanks in part to their assorted gaffes—these also proved temporary. News coverage of both candidates was actually quite balanced.

The summer of 2012 left Obama, the favorite, with a slim lead—one that was predictable but not entirely comfortable. He was probably right not to wear those socks. Meanwhile, Romney was hoping for a comeback that did not come.

The “Mathematically Impossible” Favorite

Since 1948, incumbent presidents running in growing economies have typically won elections, and those running in declining economies have typically lost. As we showed in chapter 2, even modest economic growth in an election year has been sufficient, as voters tend to weight recent trends most heavily. At the end of 2011, growth in 2012 was forecasted to be large enough to make Obama the favorite. One survey suggested that GDP would grow at a rate of 2.4% in 2012. Based on the historical relationship between election-year growth in GDP and presidential election outcomes, this growth rate would have predicted a 2- to 3-point Obama victory.5

The problem for Obama in the summer of 2012 was that this forecasted growth rate had not come to pass. Indeed, even when this forecast came out, it was already more pessimistic than the forecast before it (which predicted 2.6% growth). Actual economic growth would bear out this pessimism. In the first quarter of 2012, GDP grew at an annualized rate of 2.0%. In the second quarter, it grew at an annualized rate of 1.3%.6 Combined with the stagnant unemployment rate, the economic picture was darkening at precisely the wrong time for Obama.

Obama’s situation resembled that of previous Democratic incumbents. Democratic presidents seeking reelection have typically experienced lower rates of economic growth in their election year than in other years. For Republican incumbents, the opposite has been true: in election years, economic growth has increased at a faster rate than in other years. In other words, presidents of both parties have presided over economic growth, on average, but that growth has not occurred at the right time to maximize Democrats’ electoral advantage. Because voters weight election-year growth more heavily, this asymmetry has paid dividends for Republican presidential candidates, giving them 3 to 4 points more of the vote, on average.7

But even with the slowing economy, was Obama the underdog? Looking at isolated indicators, it was easy to believe he was. For example, growth in personal income was sluggish and, taken alone, forecast an Obama defeat.8 Moreover, consumer sentiment in the first half of 2012 plateaued as the economic news worsened. Had it continued on its previous trajectory, Obama’s chances would have looked good. Instead, consumer sentiment looked more like it did during George H. W. Bush’s first term than it did at the same point in the first terms of incumbents who, unlike Bush, were reelected.9

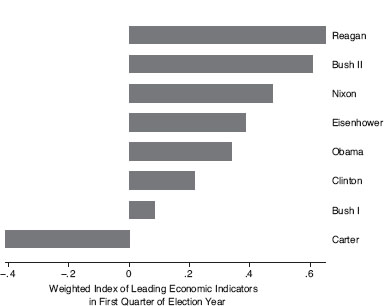

But other indicators did not tell this same story. Perhaps the most important of these was the inflation rate, which remained at historical lows. Analysts who surveyed a large set of economic indicators concluded that Obama was still the favorite, despite the slowdown in growth in early 2012. For example, political scientists Robert Erikson and Christopher Wlezien examined the Conference Board’s Leading Economic Index, which is comprised of ten different economic measures. Based on analysis of presidential elections from 1952 to 2008, the index suggested Obama was the favorite. Figure 5.1 shows why this was possible. For each elected incumbent president who was running for reelection, the figure presents the summed value of this economic index from inauguration through the first quarter of the reelection year, weighted so that more recent quarters count more heavily. The value of this index under Obama was higher than it was under the two incumbents who lost, Jimmy Carter and George H. W. Bush, and under Clinton in 1996, when he won.10

Figure 5.1.

Index of economic indicators for incumbent presidents.

The figure depicts the value of the Conference Board’s Leading Economic Index, summed across these incumbents’ first term until the first quarter of the election year for these incumbents. The index is weighted so that recent quarters count more heavily.

It was very difficult for some commentators to believe that an economy slowly recovering from a painful recession and financial crisis still favored the incumbent. In May, New York Times columnist David Brooks wrote, “Why is Obama even close? If you look at the fundamentals, the president should be getting crushed right now.”11 Election analyst Charlie Cook expressed a similar sentiment in August: “Incumbents generally don’t get reelected with numbers like we are seeing today.”12 In September, Politico’s Jonathan Martin wrote: “If it was true that winning elections is mostly a matter of numbers—as some political scientists and campaign operatives like to argue—Barack Obama’s reelection as president should be close to a mathematical impossibility.”13 Although it was true that certain economic indicators looked less favorable for Obama, a broader survey of indicators revealed the opposite. Moreover, a review of various election forecasting models—most of which used some combination of factors like economic indicators, presidential approval, and early trial heat poll numbers—found that, taken together, these models predicted that Obama had a 60% chance of winning.14 The election was far from a lock for Obama, but he was more likely to win than to lose. And even if this assessment seemed overly optimistic for Obama, 2012 was still not a year in which he should have been “crushed” or in which his reelection was an “impossibility.” If history were any guide, Obama was still likely to win.

Predictably Partisan

As the summer campaign got under way in earnest, it might have seemed as if Obama and Romney were in a similar, and unfortunate, position: suddenly unpopular within their own party. Reports suggested that the two parties were struggling—not with each other but internally. In Carl Cannon and Tom Bevan’s summary of the Republican primary, they wrote, “True, Mitt Romney ended up winning the nomination. But he did so with a split Republican base.”15 Meanwhile, Obama was said to face a “a growing rebellion on the left as he courts independent voters and Republicans with his vision for reducing the nation’s debt by cutting government spending and restraining the costs of federal health insurance programs.”16 Fights within political parties are often a tempting story for the news media, since intraparty squabbles are more unusual than fights between the political parties. New York Times columnist Gail Collins described one or both of the allegedly fractious parties as “rabid guinea pigs in a thunderstorm,” “a herd of rabid otters,” and “rabid squirrels” in 2009 and 2010.17

But presidential campaigns tend to pull each party together, not drive them to internal collapse, belying the many stories about these fractured, divided, rebellious parties—to say nothing of stories that suggest the possible obsolescence of political parties themselves.18 In presidential elections, partisanship reigns, and predictably so.

Among Americans, political partisanship is on the rise. This may seem counterintuitive on its face. Time and time again we are told that political independents are the “the vast middle ground” or the “the fast-growing swath of voters.”19 But this misses a crucial fact: most independents actually identify with a party, at least to some extent. When you ask survey respondents who identify as “independent” if they lean toward the Democratic or Republican Party, most in fact do. In 2008, only about 11% of Americans were true or “pure” independents, according to the canonical data in the American National Election Study (ANES), and this number was smaller among actual voters, since independents are less likely than partisans to vote.20 In fact, the fraction of pure independents has declined over time; it was 18% at its high point in 1974.

Identification with a political party, even if nudging is required to reveal it, is not only pervasive but consequential and increasingly so. Despite all of the ink spilled about fractured parties, in contemporary presidential elections the vast majority—typically near 90%—of partisans vote for their party’s candidate when there is no serious third-party candidate (and loyalty is still high when there is such a candidate). A similar rate of loyalty is evident even among independents who lean toward a party. They look much more like true partisans in terms of their voting behavior than they do pure independents. For example, in 2008, “pure independents” who reported voting in the presidential election split 51%–41% for Obama, with the remainder voting for another candidate. The vast majority of Democrats (90%) voted for Obama, and so did 90% of independents who leaned Democratic. Similarly, the vast majority (92%) of Republicans voted for John McCain, as did 78% of independents who leaned Republican. Independent “leaners” are certainly not identical to partisans in every respect, but they tend to act like loyal partisans in presidential elections.

These patterns are not unique to 2008. Party loyalty has increased generally. As the Democratic and Republican parties have taken ever more distinct positions on issues, partisans have better sorted themselves ideologically—with liberals increasingly identifying as Democrats and conservatives as Republicans.21 There is less and less reason for partisans to stray from the fold.

Even if they were tempted to stray, the campaign itself helps prevent that. Strengthening people’s natural partisan predispositions is one of the most consistent effects of presidential campaigns. Democrats or Republicans who initially feel a bit uncertain or unenthusiastic about their party’s nominee will end up dedicated supporters. Scholars have documented this for a long time. One of the earliest studies of presidential elections, which followed voters during the 1940 campaign, found this: “Knowing a few of their personal characteristics, we can tell with fair certainty how they will finally vote: they join the fold to which they belong. What the campaign does is to activate their political predispositions.”22

This is why a presidential nominee who emerges from a hotly contested primary can so readily consolidate support within the party. It may also explain why divisive primaries have not appeared to hurt the presidential nominee in the general election.23 The hotly contested 2008 primaries are a good example. In states where the primary was very competitive, Obama actually did a little bit better in the general election. One possible reason was that competitive primaries forced Obama to build up his campaign organization and actually made it stronger for the general election.24 Ultimately, despite the protracted battle between Obama and Hillary Clinton, supporters of Clinton or any of the other Democratic candidates tended to vote and to vote for Obama at high rates.25

What was remarkable about the 2012 election was just how quickly partisans gravitated to their party’s candidate. Democrats and Republicans were predictably partisan even before the general election campaign got under way—in fact, even before Romney sewed up in the nomination. Only days after Santorum dropped out, the very first Gallup tracking poll found that 90% of Republicans supported Romney in a head-to-head race with Obama, while 90% of Democrats supported Obama. Large majorities of both parties also said that they definitely planned to vote in November.26 This was true even though about a third of Republicans said they would have preferred another candidate to Romney.27 The divisive Republican primary did not make for hard feelings. In fact, it was not long before reporters on the ground were writing about the “newfound enthusiasm” for Romney among Republicans.28 The campaign was rallying partisans as usual.

The predictable partisanship of most American voters had one other important manifestation: it solidified their vote intentions, making preferences stable over time. This also was no surprise: studies of presidential elections have repeatedly found that most voters know who they plan to vote for early on and do not change their minds during the campaign. In 1940, for example, the presidential campaign “served the important purpose of preserving prior decisions instead of initiating new decisions.”29 In 1980 the same thing was true: “changes in political attitudes did take place during the presidential campaign, but the magnitude of these changes was not large enough to alter many individuals’ vote predictions.”30

This was also the norm in 2012. In December 2011, the polling firm You-Gov asked 45,000 Americans who they would vote for if the presidential election pitted Romney against Obama. Among all respondents, 45% chose or were leaning toward Obama and 41% chose or were leaning toward Romney. About 4% chose another candidate and 10% were not sure. (Among respondents who were registered voters, Obama led by a similar margin, and fewer, 6%, were unsure.) How many of these voters stuck with their initial choice into 2012? Every week, when YouGov reinterviewed a different set of 1,000 of the initial 45,000 people, an impressive number of them stuck with their initial choice.

Consider the people who were reinterviewed in April, at the same time that Gallup found such high rates of loyalty among Democrats and Republicans. As Table 5.1 shows, even though four months (and essentially the entire Republican primary) had elapsed, 92% of those who supported Romney in December still supported him in April. Similarly, 96% of Obama’s supporters stuck with him. Few voters switched their votes between interviews: 4% of Romney’s initial supporters defected to Obama, and 2% of Obama’s voters left him for Romney. Similarly, 2% of Romney’s and 1% of Obama’s supporters moved into the undecided category. Most everyone appeared to know who they were going to vote for long before Mitt Romney even became the Republican nominee. This kind of stability would ultimately constrain what Obama and Romney could hope to accomplish during the campaign that followed. The basic features of the election were in place: a slowly growing economy and a high degree of partisan loyalty. If things stayed the same, not very many voters were up for grabs.

Table 5.1.

The Stability of Vote Intentions from December 2011 to April 2012.

Note: Data consist of YouGov poll respondents who were interviewed at two points in time: December 2011 and April 2012. Percentages are within each group of December respondents and should be read across the rows. N = 3,594

The Misunderstood Undecided Voter

But what about the voters who were up for grabs? These voters, the proverbial “undecided voters,” are sought after by political campaigns but often mocked by pundits and commentators. The 2012 election was no exception. The Republican pollster Jan van Lohuizen called undecided voters “cave dwellers.”31 MSNBC’s Chris Matthews unleashed this diatribe:

People say, “this election’s hard for me to decide.” You’d have to be a bonehead not to be able to decide between these two guys. It is so easy. … People are still scratching their heads trying to decide what’s—well, gee, just don’t vote. Don’t bother if you have to think at this point. What’s your problem?32 Saturday Night Live aired a parody in which serious-looking “undecided voters” asked “meaningful” questions: “When is the election?” “What are the names of the two people running? And be specific.” “Who is the president right now? Is he or she running?” “Can women vote?” Actually investigating the prevalence of such stereotypes is hard. In a survey of 1,000 people during a typical presidential campaign, there will be only a few dozen undecided voters—too few for statistical analysis. But by combining ten different You-Gov surveys from May through July—a combined sample of 10,000 respondents—we took an unusually nuanced look at 592 respondents who declared themselves undecided.33

As with most great comedy, the Saturday Night Live skit contained a kernel of truth. Compared to voters who stated a preference for a candidate, undecided voters in the summer of 2012 were indeed less attentive to politics. Only a quarter of undecided voters said they were very interested in politics compared to 60% of “decided” voters. They were also less informed about the political world. Only 38% could correctly identify Speaker of the House John Boehner as a member of the U.S. House of Representatives, whereas 63% of decided voters could do this. Undecided voters did no better than guessing when asked whether the Republican Party or Democratic Party was more conservative, whereas 80% of decided voters knew it was the former. Undecided voters were also, and unsurprisingly, less likely to vote: 30% of them reported that they rarely make it to the polls, compared to 8% of those who had a candidate preference. That said, undecided voters were hardly the ignoramuses presented on Saturday Night Live. They may have followed politics less closely, but that did not mean they knew nothing about it.

Moreover, most of these undecided voters had political identities and opinions about political issues. Despite the common stereotype that undecided voters are independents who do not affiliate with a political party, only about 30% of them were independent and an additional 7% were not sure of their party identification. The remaining 63% identified with or leaned toward either the Democratic or Republican Party.

In fact, what most distinguished these undecided voters was not that they were independents but that they were disgruntled partisans. A more academic description of them is “cross-pressured”—that is, having political opinions that were in some tension with each other. That cross-pressured voters exist, and are often less interested in elections, has been well-known to scholars for more than sixty years.34 In 2012, cross-pressures were evident in various ways.

Undecided Democrats were unenthusiastic about Barack Obama—something relatively rare given the increasing partisan polarization in attitudes toward the presidents that we have described. Whereas 79% of decided Democrats approved of Obama, only 17% of undecided Democrats did. As one undecided voter who had supported Obama in 2008 put it, “he has not lived up to the ‘hope and change’ he professed. … He seems stuck.”35 Undecided Democrats tended to disapprove of the president’s performance on a range of issues—from the economy to the deficit to health care—and also expressed less favorable attitudes about the president’s personality.

Undecided Republicans were similarly uninspired by Romney. The majority, 64%, believed that he “says what he thinks people want to hear,” while only 8% believed he “says what he believes.” (Decided Republicans were more evenly divided between these alternatives.) In fact, undecided Republicans had a less favorable view of Romney in the summer of 2012 than they did in December 2011. Undecided Republicans were cross-pressured in another sense: their policy views were more at odds with those of their party. They were twice as likely as decided Republicans to support gay marriage but half as likely to favor repealing the Affordable Care Act.

The prevalence of cross-pressured partisans among undecided voters raised an interesting possibility: that they could be lured to the other side. In fact, presidential campaigns can make defection among cross-pressured voters more likely.36 At the same time, campaigns can also herd undecided partisans back into the fold. In 2012, little about the undecided Democrats and Republicans suggested that they were all that enthralled with the other guy: most undecided Democrats did not like Romney and most undecided Republicans did not like Obama. Ultimately, these undecided voters could have provided a significant boon if they broke for one candidate, and the candidates were crafting messages with this very much in mind.

Jobs, Jobs, Jobs

“4.3 million new jobs,” declared an ad for Obama. “President Romney’s leadership puts jobs first,” said an ad of Romney’s. As the general election campaign got under way, there was no doubt what issue was foremost on voters’ minds and in the messages of both candidates. In a May Washington Post/ABC News poll, 52% said that the economy and jobs were the “single most important issue” in their choice for president. No other issue attracted more than single digits. In 2012, Romney’s and Obama’s campaign teams took a look at the most salient issue—the state of the nation’s economy—and came up with the same answer: “the economy is on our side.” They both could not be right.

A candidate’s message is the argument for his or her election boiled down to a few sentences or even a few words. These messages are often developed well before the general election begins in earnest. They can be modified or recalibrated but are replaced wholesale with caution. The candidate changing his or her message is usually the candidate who is losing, and a new message is taken as further proof of the challenges this candidate faces.

Candidates design their messages around the context in which they find themselves—the hand they are dealt, as we called it in chapter 2. There are personal constraints. For example, an older candidate who has served in government for a long time cannot easily present him- or herself as a candidate of “new ideas.” He or she may be instead, as was Hillary Clinton in 2008, the candidate of “experience.” There are constraints that come from the issues that are salient to voters. As in 2012, candidates tend to emphasize the issues most important to voters, which means that opposing candidates are often discussing many of the same things.37 To do otherwise risks appearing inattentive or uncaring.

In a typical presidential campaign, the economy tends to benefit one party: the incumbent’s party when the economy is good and the challenger’s party when the economy is poor. The candidate who benefits from the state of the nation’s economy should emphasize the economy as a campaign issue. This candidate can take credit for good times, as Ronald Reagan did in 1984 when he called it “Morning in America,” or blame the incumbent party for bad times, as Barack Obama blamed George W. Bush in 2008. In The Message Matters, Lynn Vavreck calls this type of candidate a “clarifying” candidate—one who must clarify which party is responsible for the economy in order to win.38 Specifically, a clarifying candidate should take credit for the growing economy or blame the opponent for a shrinking economy. Not doing so can be a mistake. Al Gore’s 2000 campaign shows what can happen when clarifying candidates fail to attach themselves to the incumbent party’s strong economic record.

Candidates disadvantaged by the economy—the “insurgent” candidates in Vavreck’s framework—have a different, and arguably harder, task. They must shift the focus of the election to an issue other than the economy. Specifically, they must find an issue on which their position is more popular than their opponent’s and on which the opponent is committed to an unpopular position. Insurgent issues are often difficult for candidates to find. One reason for this is that their opponents sometimes can and do wriggle out of their previous position on the issue and simply adopt the same position as the insurgent candidate—effectively neutralizing the issue. The clarifying candidate must be truly stuck with his unpopular position for the insurgent issue to win votes.

Amid the weak economy in 1980, the incumbent Jimmy Carter was the insurgent candidate and chose to attack Reagan on nuclear weapons and arms control, suggesting that electing Reagan would only increase the likelihood of nuclear war. But Reagan, who was not irrevocably linked to the view Carter accused him of, simply took the same position as Carter, declaring his support for reducing the number of nuclear weapons and thereby neutralizing Carter’s attack.39 In fact, in presidential elections from 1952 to 2008, only four insurgent candidates have won: Kennedy, Nixon, Carter, and George W. Bush. For example, Kennedy did so by shifting the discussion to the New Frontier and to a Cold War competition with the Soviets over everything from nuclear missiles—the “missile gap” that Kennedy highlighted—to space exploration. Because there was no easy way to disprove the existence of the missile gap, it was difficult for Nixon, as a member of the administration who allegedly presided over this gap, to claim otherwise.

What made 2012 unusual was that, at the outset of the general election campaign, both candidates behaved like clarifying candidates—something that has happened in just one other postwar election (1992). To measure the prevalence of different issues in Romney’s and Obama’s campaign messages, we drew on campaign advertising data collected by the Campaign Media Analysis Group (CMAG). Figure 5.2 reports the percentage of the ads aired between May and July 2012 that mentioned various issues.40 During this time, Obama and allied Democratic groups aired the majority of ads (179,463 and 19,781, respectively), although Romney, the Republican National Committee (RNC), and allied Republican groups aired nearly as many (166,399 combined). These numbers are important to keep in mind when comparing the percentages in Figure 5.2, especially since Democratic groups aired relatively few ads.

That both Romney and Obama acted like clarifying candidates is evident in how much of their summer advertising mentioned jobs: 82% of ad airings for both candidates. This far outstripped any other theme, although both candidates devoted attention to the budget, government spending, and taxes, too. Obama’s advertising also mentioned several other issues, including Romney’s tenure at Bain Capital, while Romney focused on a smaller set of issues, including energy and health care. But clearly the economy dominated each candidate’s advertising. As Figure 5.2 shows, the economy also figured prominently in the ads aired by the RNC and by the outside groups on both sides. The economy was also the dominant issue in news coverage.41

But Obama and Romney framed their economic appeals very differently. The Obama campaign focused on the extent to which the economy had improved. One ad reminded voters that since Obama’s inauguration there had been “26 straight months of private sector growth” and “4.25 million jobs created.”42 An animated graphic showed job losses throughout 2008—colored in Republican red—and then job gains soon after Obama took office, which of course were colored Democrat blue. The ad’s tagline was, “Do we really want to change course now?” In another ad, Obama took a similar tack. He first reminded viewers of what he confronted when he took office: “We’re still fighting our way back from the worst economic crisis since the Great Depression.” While acknowledging that “we’re still not creating [jobs] as fast as we want,” he then cited the “4.3 million new jobs” that had been created, promoted his own plan for creating more jobs, and criticized Congress for failing to act on it.43 The Obama campaign’s message was simple: even if times were not great, they were at least getting better, and because of the incumbent.

Figure 5.2.

Issues mentioned in Obama and Romney advertising, May–July 2012.

The figure depicts the estimated percentage of Obama and Romney ad airings in May–July 2012 that mentioned each of these issues. Data from the Campaign Media Analysis Group.

Romney’s economic message committed him to jobs as well: “President Romney’s leadership puts jobs first,” said one early ad titled “A Better Day.”44 The difference, of course, was how Romney portrayed the health of the economy under Obama. After the May jobs report showed unemployment ticking up, Obama suggested at a June 8 press conference that the real issue was job losses in state and local government while “the private sector is doing fine.” Romney pounced. One ad consisted almost entirely of newscasters like Diane Sawyer reacting with concern to the jobs report, juxtaposed with Obama’s “private sector” comment.45 The tagline then read, “Has there ever been a president so out of touch with the middle class?” followed by a link to the webpage www.obamaisntworking.com. Another ad pivoted off Obama’s comment with testimonials from “middle-class workers” describing the challenges they were facing: layoffs, long-term unemployment, bankruptcy, no health care, a slashed pension. One man said, “Sometimes I feel like a failure.” Romney’s message was the opposite of Obama’s: the economy was still terrible, Obama was to blame, and only Romney could bring about that “better day.”

Within Romney’s messaging there were also hints of an insurgent campaign theme. The focus on the budget—present in 40% of Romney’s ads during May–July—shifted the subject from the economy to government spending and the size of the federal deficit. In other ads, Romney touted his own record of balancing the budget as Massachusetts governor and criticized Obama for his “broken promise” to rein in government spending and the deficit.46 Instead, Romney argued, Obama created a “debt and spending inferno.”47 This message was often linked to Romney’s broader message on the economy: In “A Better Day” the voiceover says, “From Day 1, President Romney focuses on the economy and the deficit.” Romney made the argument that the debt and government spending hurt the economy—for example, by requiring the United States to borrow more money from China, which Romney warned was taking away American jobs as firms relocated their operations to China where labor was cheaper.48 To Romney, smaller government—embodied in the “Cut the spending” banner that hung at his early campaign appearances—was an economic stimulus plan in its own right. This message set up a different kind of comparison to Obama, moving beyond just the employment numbers to implicate Obama’s domestic policymaking. But this message was still subordinate to Romney’s broader critique of Obama’s economic record.

Navigating Public Ambivalence about the Economy

Romney and Obama could not both win the argument about the state of the nation’s economy even if they thought they could. What were the promises and pitfalls that lay ahead as each centered his campaign on the economy? Why did they both think this was a winning strategy? Answering these questions means understanding the public’s ambivalence about the economy and issues related to it. Americans’ “on the one hand, but on the other hand” mentality presented opportunities and challenges for both Obama and Romney. As we have argued, the objective economy favored Obama. But public views of the economy did not depend wholly on statistics, and Obama faced a public concerned about the economy and his stewardship of it. That gave Romney an opening he could exploit. But Romney also faced a public that was not ready to embrace him as the alternative to Obama.

Americans’ concern about the economy was very evident in the summer of 2012. In a mid-May YouGov poll, respondents were asked about the condition of the economy both in the recent past and at that moment. When asked what the condition of the economy had been in 2008, most said that it had been “fairly bad” (36%) or “very bad” (49%). When asked about the economy “these days,” 42% said fairly bad and 28% said very bad—a positive trend, but one that still left 70% of the country dissatisfied with the economy. When asked directly about the trend in the economy, Americans did not seem optimistic. Among respondents in the May, June, and July YouGov surveys, 37% said the economy was getting worse and 36% said it was the same.49 Only 21% said that it was getting better, and the remainder was not sure. These assessments had barely changed from when these same respondents were interviewed in December 2011. At this point, the public’s pessimism seemed persistent.

Naturally these assessments were also colored by partisanship: only 17% of Democrats said that the economy was getting worse, compared to 60% of Republicans. But independents who did not lean toward either party were closer to Republicans: 43% said the economy was getting worse. Undecided voters also tilted toward pessimism. The plurality (45%) thought that the economy was the same, but many more said that it was getting worse (34%) than it was getting better (6%).

Given this pessimism, it is not surprising that voters tended to disapprove of Obama’s stewardship of the economy. Only 36% approved of Obama—and even fewer among independents (24%) and undecided voters (18%). The intensity of opinion was not in Obama’s favor either: independents and undecided voters were more likely to “strongly” disapprove than only “somewhat” disapprove.

There was one silver lining for Obama: people tended to blame the state of the economy less on him than on his predecessor, George W. Bush. In mid-April, as we reported in chapter 2, 43% of Americans said that Obama deserved a great deal or a lot of the blame, while 51% said this of George W. Bush. The same was true in May and June, according to other polls by the Washington Post and Gallup.50 But in a late July YouGov poll, Obama’s advantage waned: 46% blamed Obama and 48% blamed Bush. Independents and undecided voters still blamed Bush more, but the trend was not good news for Obama. His message about the economy—essentially, “it’s getting better, so leave me in charge”—confronted a skeptical public. It is not hard to see how Romney thought this was a plausible weakness to exploit.

However, Romney’s decision to focus on the economy was, in another sense, questionable. Objective economic conditions were not in his favor, and the four previous presidential candidates who focused on the economy despite this disadvantage lost: George McGovern, George H. W. Bush in 1992, Bob Dole, and John McCain.51 The Romney campaign’s point of historical reference, however, seemed to be Jimmy Carter in 1980.52 They apparently believed that although Obama led now, Romney would come from behind at the end, as they believed Reagan had. This was a mistaken view of the 1980 race; Reagan actually led for much of the fall.53 Moreover, as we have argued, economic conditions in early 2012 were much better than they had been in early 1980. Obama was also far more popular than Carter.

Another challenge for Romney was this: even if voters were pessimistic about the economy and frustrated with Obama’s stewardship of the economy, they were not yet ready to embrace Romney as an alternative. For one, Americans were somewhat uncertain as to how a President Romney would affect the economy and, among those who had an opinion, were no more confident in him than in Obama. In early June, a YouGov poll asked respondents how the economy would be affected if Obama or Romney were elected president. In Obama’s case, 30% thought that the economy would get better and 39% thought it would get worse. The remainder thought it would stay the same (15%) or did not know (16%). By contrast, 27% did not know how the economy would do under Romney. Among those who had an opinion, Romney was no more favored than Obama: 25% thought the economy would get better and 33% thought it would get worse. The pattern was similar among undecided voters.

Second, Americans were not convinced that Romney understood the challenges they faced. In a mid-June YouGov poll, 44% said that Obama understood “the current economic situation facing most Americans” either very or somewhat well, while 48% said he understood it not too well or not well at all. By contrast, fewer Americans (37%) believed that Romney understood what Americans were facing while 49% believed he did not. The difference, of course, was that twice as many Americans were not sure about Romney (14%) as about Obama (7%).

Even more fundamentally, Americans tended to believe that Romney was less likely to “care about” them than Obama was. They also saw Romney as more concerned about wealthier Americans than about the middle class and poor. Romney’s challenges in this domain began well before the general election was really under way. Right after the Iowa caucuses, in a January 7–10 YouGov poll, we asked respondents how well the following phrases described Obama and Romney: “is personally wealthy,” “cares about people like me,” “cares about the poor,” “cares about the middle class,” and “cares about the wealthy.”54 Respondents could answer very well, somewhat well, not very well, or not at all well.

Even in this poll, conducted at the outset of Gingrich’s and Perry’s attacks on Romney’s time at Bain Capital, Romney’s disadvantages were evident. The disadvantage was not so much about personal wealth: the vast majority of respondents thought that “personally wealthy” described Romney (89%) and Obama (84%) very well or somewhat well, although many more said “very well” in reference to Romney than Obama. More people described Obama as caring about the poor (62% said somewhat or very well versus 38% for Romney), the middle class (56% versus 49%), and “people like me” (51% versus 42%). But more, 84%, described Romney as caring about the wealthy. Only 58% said that of Obama. Among true political independents, who lack the party loyalties that shape such responses, there were similar gaps in views of Obama and Romney.

Romney faced an additional disadvantage: how these attitudes were structured. The more voters thought “personally wealthy” described Romney, the more they thought that “cares about the wealthy” described him. But people’s belief that Obama was personally wealthy did not translate as strongly into the belief that he cared about the wealthy.55 A similar contrast arose with regard to caring about the wealthy versus other groups. Voters who believed that Romney cared about the wealthy were less likely to think that he cared about “people like me,” the poor, or the middle class. But voters who believed that Obama cared about the wealthy were actually more likely to think that he cared about these other groups.56 Romney’s empathy gap was not just about which candidate was perceived to care more for average Americans, it was also about whether caring about the wealthy meant caring less about everyone else.

Some of Romney’s disadvantage was endemic to the Republican Party, which has traditionally been seen as aligned with wealthy interests. In 1953, a Gallup poll asked respondents, “When you think of a people who are Democrats, what type of person comes to mind?” About 38% selected words like “working class,” “middle class,” and “common people” while only 1% selected words like “rich” or “wealthy.” The opposite was true when asked about Republicans: 31% picked words like “wealthy” and “business executive” while only 6% chose “working class” and its kindred. Over forty years later, in a 1997 poll, the same findings reoccurred.57 In 2012 these same stereotypes were again in evidence. When asked which party would be “better for” different groups, majorities or pluralities of respondents said that the Democrats would be better for the poor and middle class, while the majority said that the Republicans would be better for Wall Street.58 Perhaps because of these images of the Republican Party, Republican presidential candidates have often faced an “empathy gap.” Voters have been more willing to say that the Democratic candidate “cares about people like me” than to say this of the Republican candidate in every presidential election from 1980 to 2008.59

So Romney’s situation was nothing new or even unusual. But it was not inevitable that the Republican Party and Romney would face an empathy gap. Rick Santorum showed that it was possible for a Republican candidate to be perceived as in touch with the middle class. In a February poll, voters perceived Santorum as more similar to Obama than Romney. For example, 49% said that Santorum cared about “people like me,” while 51% said that of Obama but only 35% said that of Romney.60

Of course, the point is not that Republicans should have nominated Santorum instead of Romney. There was no reason to think that Romney’s “empathy gap” would inevitably be fatal. Republican presidential candidates have routinely won without closing this gap.61 But the question was whether Romney could be one of those winners, especially when the Obama campaign would soon seek to magnify this image of Romney as a rich guy who cared more about the wealthy than the middle class. For while the Romney campaign believed that voters’ shrinking incomes were Obama’s pressure point, Obama believed that Romney’s income was his.

“What about Your Gaffes?”

Although political candidates try to have a disciplined message, unscripted moments happen. And when they do, commentators take note. “Here’s an unpopular opinion,” wrote the Washington Post’s Chris Cillizza on June 10. “Political gaffes matter.”62 He was writing right after Obama suggested the “private sector was doing fine.” Political gaffes often fascinate reporters and commentators. Most days on the campaign are repetitive, as candidates deliver the same speech in a different town. But once in a while something happens that is unexpected and, from the candidate’s point of view, undesired. These blunders almost always make the news, since they may be the only interesting thing that has happened on the campaign trail in a long time.

But do blunders matter to voters? Often not so much, and this election was no exception. The summer of 2012 saw a series of gaffes that received ample attention by the press and seemed likely to shape the race in critical ways, as voters might use them to make inferences about the candidates’ competence, empathy, and readiness to lead. But as it turned out, the gaffes in May, June, and July were largely non-events. Sometimes “unpopular opinions” are unpopular for a reason.

After Obama’s “private sector” comment, the summer provided several other opportunities to test Cillizza’s proposition. On July 13, Obama spoke his famous phrase “you didn’t build that” in a campaign speech in Roanoke:

There are a lot of wealthy, successful Americans who agree with me—because they want to give something back. They know they didn’t—look, if you’ve been successful, you didn’t get there on your own. You didn’t get there on your own. I’m always struck by people who think, well, it must be because I was just so smart. There are a lot of smart people out there. It must be because I worked harder than everybody else. Let me tell you something—there are a whole bunch of hardworking people out there.

If you were successful, somebody along the line gave you some help. There was a great teacher somewhere in your life. Somebody helped to create this unbelievable American system that we have that allowed you to thrive. Somebody invested in roads and bridges. If you’ve got a business—you didn’t build that. Somebody else made that happen. The Internet didn’t get invented on its own. Government research created the Internet so that all the companies could make money off the Internet.

The point is, is that when we succeed, we succeed because of our individual initiative, but also because we do things together. There are some things, just like fighting fires, we don’t do on our own. I mean, imagine if everybody had their own fire service. That would be a hard way to organize fighting fires.63

Obama was apparently making the case for the positive role of government in people’s lives. But Republicans accused the president of disrespecting small business owners and entrepreneurs. It was, said Romney in an e-mail solicitation, “a slap in the face to the American dream.”64

The tables were soon turned, however. In late July, Romney took a well-publicized trip to Britain, Israel, and Poland to demonstrate his foreign policy expertise. In London, just days before it would host the Olympic Games, Romney insulted the mayor by saying he had concerns over the city’s preparedness, provoking a British tabloid to call him “Mitt the Twit.”65 In Israel, Romney insulted Palestinians by suggesting that “cultural differences” explained why Israel was more economically prosperous than Palestinian areas. In Poland, a Romney staffer barked “kiss my ass” at a member of the traveling press who shouted, “What about your gaffes?” to Romney at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier. A CNN headline summed up the week: “Was Romney’s trip ‘a great success’ or gaffe-filled disaster?”66 No candidate wants that to be the question asked after a trip abroad.

Gaffes are supposed to matter because the twenty-four-hour news cycle and the opposing side’s eagerness to publicize gaffes make it nearly impossible for voters to avoid hearing about them. This was what Cillizza argued about Obama’s “private sector” comment: “Is there anyone paying even passing attention to politics who hasn’t seen the Obama clip five times at this point—which, by the way, is less than 96 hours after he said it? Answer: no.”67

The actual answer was yes. To be sure, gaffes can generate some news coverage, and that coverage may not be favorable. In Figure 5.3, we present the daily volume of news coverage of Romney and Obama for May through August. (We presented similar figures for the Republican primary candidates in chapters 3 and 4.) This includes the number of “mentions” of each (the gray line) as well as the volume weighted by the coverage’s tone (the black line). The graph is scaled so that the vertical axis could accommodate the spikes in news coverage that would come in the fall. This helps put the volume of coverage in the summer in perspective.

The question is whether any of these gaffes generated a spike in news coverage, visible in the gray line, and unfavorable coverage to boot, in which case the black line should dip below zero, where negative coverage outweighs positive coverage.

Neither of Obama’s gaffes produced much in the way of a spike in coverage or unfavorable coverage. The trend in Obama’s news coverage was driven more by a natural periodicity—coverage tended to drop off on Saturday—punctuated by spikes when he endorsed same-sex marriage and when the Supreme Court upheld the Affordable Care Act, a.k.a. “Obamacare.” For the most part, coverage of Obama in May and June was positive, except in early May when he traveled to Afghanistan and on May 20 and June 1, when first Newark mayor Cory Booker and then Bill Clinton contradicted the Obama campaign’s attacks on Romney’s experience at Bain Capital.68 The dip in the favorability of Obama’s coverage came in July, about three days after his “you didn’t build that” remark. This was driven in part by a Romney effort to push back against Obama’s attacks on his time at Bain Capital. Romney seized on Obama’s remark and argued that Obama wanted Americans to be “ashamed of success.”69 However, Obama’s remark was not the only reason for this less favorable news coverage, since Romney also accused him of rewarding supporters with federal grants and loan guarantees.

For most of the spring and early summer, coverage of Romney resembled coverage of Obama, rising and falling each week with the occasional spike around a notable event, such as a well-received speech Romney gave at Liberty University and his receiving enough delegates to clinch the nomination in late May.70 But in July, news coverage of Romney was more negative than positive most every day. Although Romney was already experiencing unfavorable coverage leading into his trip abroad, the trip did not help. Coverage of Romney was negative every single day he was traveling.

Figure 5.3.

Trends in Romney’s and Obama’s news coverage.

The gray line represents the volume of mentions of each candidate. The black line represents the volume of mentions, weighted by the tone of the coverage. When the black line is above 0, the coverage is net positive; when it is below 0, the coverage is net negative. The data span the period from May 1 to August 31, 2012.

However, this coverage did not necessarily penetrate quite as far as Cillizza believed. It is always easy for anyone who follows politics professionally—such as journalists and political scientists—to assume that everyone else does likewise. But many ordinary Americans, if not most of them, have better things to do than stay glued to cable news, and they may be oblivious to whatever the chattering classes are chattering about.

To illustrate, take Obama’s “private sector is doing fine” comment. In a June 16–18 YouGov poll—about a week after the press conference—we asked this question:

In a press conference last week, President Obama was asked about the state of the economy. How did he describe economic growth in the private sector?

• The private sector is doing fine.

• The private sector is struggling.

• The private sector is mostly the same as it was.

• I didn’t hear what he said.

In total, 47% of respondents gave the correct answer. Nine percent said “struggling” and 4% said “mostly the same.” About 39% said that they had not heard. More than half of Americans had not heard or did not know what Obama had said.

This leads to an even more important point: the people who are likely to have heard about a presidential candidate’s gaffe are the least likely to change their minds. People who are interested in politics enough to follow the news also tend to have stronger opinions about politics—ones they are reluctant to change. This is why undecided voters in this June poll were much less likely to know about Obama’s comment. And this is why the voters who did know about Obama’s comment expressed a preference for Obama or Romney that was no different than the one they expressed when they were originally interviewed in December 2011.71 Politically engaged people have stable preferences in presidential elections that cannot be easily shifted by gaffes.72

The same stability was evident in the national polls throughout the summer. Figure 5.4 depicts Obama’s and Romney’s standing in the polls, with demarcations for these gaffes and Romney’s selection of Paul Ryan as his running mate. We drew on polling averages developed by Stanford University political scientist Simon Jackman for the Huffington Post’s Pollster site.73 These averages not only helped separate true movement in the polls from random fluctuations due to sampling error, but they also took into account the systematic tendency for some polling firms to be a bit more “pro-Democratic” or “pro-Republican” than other firms.74 This tendency, sometimes called a “house effect,” usually has to do with idiosyncrasies in a polling house’s methodology, not a deliberate attempt to favor one party.

Figure 5.4.

Poll standing of Obama and Romney in spring and summer of 2012.

The figure presents averages from state and national polls developed and presented by the Huffington Post’s Pollster site.

There was little evidence of a notable shift after any of these gaffes. Apples-to-apples comparisons of individual pollsters showed the same thing. The Gallup poll conducted mostly the week before Obama’s “you didn’t build that” comment had Obama up 2 points. The Gallup poll conducted the week after had Obama up 1 point—a statistically insignificant shift. Rasmussen’s polling and the RAND American Life Panel also suggested little to no movement. YouGov polls actually suggested a small change in Obama’s favor. The same stability was evident before and after Romney’s foreign trip.75

Voters who were potentially persuadable were somewhat more sensitive to these events, but not in a way that produced a consistent trend in favor of either candidate. We considered voters as “potentially persuadable” if, when first interviewed in December 2011, they said that they were undecided or supported some other candidate besides Romney and Obama. This was about 20% of respondents. We have already described the attitudes of undecided voters and why this made them up for grabs. The same was true of those supporting a third-party candidate, since typically many of these voters end up supporting a major-party candidate. Although by the summer, some of these voters may have chosen Obama or Romney, their initial uncertainty in December 2011 suggests that those choices were not necessarily set in stone. Examining the opinions of these voters when they were interviewed again in the summer suggests whether these gaffes pushed susceptible voters either way. In particular, we investigate whether they changed their vote intention as well as whether they viewed Obama or Romney more favorably.76

At two moments in particular—Obama’s private sector comment and Romney’s foreign trip—there were small but temporary shifts in persuadable voters’ attitudes about the candidates but very little shift in vote intentions. After Obama’s “you didn’t build that” line, views of Obama and Romney shifted a little bit in Romney’s favor. For the sake of easy interpretation, imagine candidate favorability as a 100-point scale ranging from very favorable views of Romney and very unfavorable views of Obama at one end to very unfavorable views of Romney and very favorable views of Obama at the other end. Between the surveys conducted just before and after Obama’s speech, the views of these persuadable voters shifted in Romney’s favor about 4 points on this 100-point scale. However, among this group, actual vote intentions shifted little across these two weeks. Across the two surveys bracketing much of Romney’s foreign trip, there was an even smaller shift in candidate favorability—about 2½ points in Obama’s favor—but virtually no shift in vote intentions.77

Ultimately, gaffes did not move the large majority of “decided” voters and moved only this minority of persuadable voters a little. Why? Part of the reason is that these gaffes did not put either candidate at a significant disadvantage in news coverage. Even Romney’s trip, which did generate negative coverage of him, took place when coverage of Obama was equally if not more negative. This balance in news coverage is another feature of the tug-of-war or dynamic equilibrium in presidential general elections. Because news coverage was balanced in the summer and because the polls themselves were stable, there was little reason to expect either one to move the other. To provide some statistical confirmation of this, we examined the relationship between polls and news coverage for May through August—looking in particular to see whether one candidate’s advantage in news coverage (depicted in Figure 5.3) translated into gains in the polls for the electorate as a whole (depicted in Figure 5.4). We found no such relationship (see the appendix to this chapter). Any ups and downs in the news coverage, including after these gaffes, did not appear to change minds.

This finding is different than the process of discovery, scrutiny, and decline in the Republican presidential primary—but predictably so. In the primary, we often found evidence of a relationship between news and polls, particularly for surging candidates like Rick Santorum. But in the general election the dynamics were much different. The two candidates were more familiar to voters and reporters alike. So Obama and Romney did not surge from obscurity to prominence in news coverage the way that several Republican presidential hopefuls did. They had long ago been “discovered,” and coverage was never going to decline until after Election Day. The general election campaign was really just an extended period of scrutiny. Unlike in the primary, voters in the general election could also rely on their own party affiliation to form opinions about the candidates. This in turn made the opinions of most voters stable and thus the horse-race polls as well.

Obama’s Gamble: The Bain Attacks

Romney’s personal wealth and experience in private equity had been a fixture of the campaign even before the summer of 2012. Romney himself made various off-the-cuff remarks that highlighted his personal wealth: offering to bet Rick Perry $10,000 in a fall 2011 debate, noting that he had good friends who owned NFL and NASCAR teams, mentioning that his wife owned not one but “a couple of” Cadillacs, and so on. That Romney took so long to release his tax returns, and then released only two years of returns, was taken by his critics as suggesting he had something to hide. Romney’s tax returns and time at Bain Capital were the subject of attacks from Newt Gingrich and Rick Perry in the primary, as we discussed in chapter 4. Now the Obama team would renew this line of attack.

The Obama campaign and its affiliated super-PAC, Priorities USA Action, sought to “define” Romney in much the same way as had Gingrich and Perry: as a wealthy person who had little in common with ordinary Americans and as a businessman more concerned about profit than people. This argument was the corollary of Obama’s positive message on the economy: take one of Romney’s apparent strengths—his business experience—and turn it into a liability.

The attacks on Romney were two-pronged. The Obama campaign focused on how Bain Capital had allegedly engaged in outsourcing—sending American jobs to countries like China and India in order to boost the bottom line of the companies it acquired and to line Romney’s own pockets with the profits. Six different ads made this argument, citing a Washington Post story as evidence.78 In perhaps the most notable ad, “Firms,” a recording of Romney singing “America the Beautiful” played as a series of headlines was interspersed with images of empty factories. The headlines proclaimed that Romney had outsourced jobs to India and had millions in a Swiss bank account and in tax havens in the Bahamas and the Cayman Islands. The ad’s tagline was “Romney’s not the solution. He’s the problem.” Fact-checkers would later conclude that this argument was, at best, half true, but nevertheless commentators said that this ad “might be the most devastating TV ad of the campaign so far.”79

The second prong of these attacks, from Priorities USA Action, presented workers who had lost their jobs because Bain Capital had bought and then shuttered the businesses that employed them. Several workers were from a steel company that had closed several years after being purchased by Bain Capital.80 One worker, Donnie Box, said that Bain Capital “shut down entire livelihoods.”81 Another, Joe Soptic, recounted how he lost his health care, which he believed delayed the diagnosis of his wife’s fatal cancer. Soptic said, “I do not think Mitt Romney realizes what he’s done to anyone, and furthermore I do not think Mitt Romney is concerned.”82 In another ad, Mike Earnest, who was laid off from a paper plant, recounted how workers at the plant had built a temporary stage, from which company officials informed them that the plant was closing. Earnest said, “It turns out that when we built that stage, it was like building my own coffin, and it just made me sick.”83 These ads questioned two things. One was Romney’s skill as an economic steward. After alleging that, under Romney, Bain Capital had bought companies from which workers were subsequently laid off, one ad asked skeptically: “Now he says his business experience would make him a good president?”84 The other was Romney’s ability to understand the middle class. Donnie Box suggested a fundamental estrangement between people like him and people like Romney: “They don’t live in this neighborhood. They don’t live in this part of the world.”85 Perhaps most succinct was the tagline in these ads: “If Romney wins, the middle class loses.”

As we showed in Figure 5.2, ads referring to Bain Capital constituted about a quarter of Obama’s advertising during the summer and about two-thirds of Priorities USA’s. But the decision to advertise early, and to emphasize Bain Capital, becomes more evident if we examine advertising volume over time. Figure 5.5 presents the number of ads aired between January and August 2012 by Obama, Priorities USA Action, and the combination of Romney, the Republican Party, and various GOP-aligned groups. We scaled the vertical axis to anticipate the large increase in advertising that would come in September and October and dwarf these early ad buys.

Figure 5.5.

Volume of television advertising in early 2012.

The figure depicts the estimated weekly number of ads aired by Obama, Priorities USA Action, and Republicans from the week ending January 15, 2012, to the week ending August 26, 2012. Data from the Campaign Media Analysis Group.

The spike in Obama’s advertising in May and June is readily evident. During these months, Obama alone was airing more ads than Romney, the RNC, and the GOP groups combined. This was the push that Obama’s team intended, but it was not about Bain. The Bain Capital ads appeared in July, and during that month they constituted a substantial fraction of Obama’s advertising (38%). By contrast, the Priorities USA ads were aired much less frequently. This is perhaps unsurprising given Obama’s well-documented reticence to embrace super-PACs as a vehicle for electioneering and the concomitant challenges Priorities USA faced when fund-raising.86 In this period, Priorities USA aired a very small fraction of the total advertising on Obama’s behalf and less than half of the advertising about Bain Capital in particular. One final and important thing to note is that the Democratic advertising edge disappeared by the third week of July. The Republicans out-advertised the Democrats for the rest of July and most of August.

Of course, television ads are also intended to reach viewers indirectly: by generating coverage in the news media—or what political professionals often call “earned media.” So it may have mattered less how often the Bain ads aired and more how much news they generated. Figure 5.6 displays not only the number of mentions of Mitt Romney in the news media (the same quantity presented in Figure 5.3) but the number of mentions of “Mitt Romney” and “Bain Capital” combined, which captures stories that focused on Romney’s career at Bain. As it turned out, Bain Capital was in the news for a very brief time and not entirely for reasons having to do with the ads themselves.

Figure 5.6.

Trends in news coverage of Mitt Romney and Bain Capital.

The gray line represents the volume of mentions of Romney. The black line represents the volume of mentions of Romney and Bain Capital combined. The data span the period from May 1 to August 31, 2012.

Despite an advertising push that began in June, coverage of Romney and Bain Capital spiked only for about one week in July—from July 12 to July 20 (which was, perhaps not coincidentally, the day of the mass shooting in Aurora, Colorado). The initial catalyst for this spike was not a new ad but a widely discussed July 12 story in the Boston Globe detailing how Bain Capital had listed Romney as CEO on government documents three years beyond the date Romney had given as the conclusion of his employment at Bain.87 This potentially extended Romney’s control from 1999 to 2002, encompassing a period during which, the Obama campaign alleged, Bain Capital had engaged in specific instances of outsourcing or shutting down businesses. The Obama campaign then suggested that misrepresenting Romney’s role might constitute a felony, outraging the Romney camp.88 Rounding out the day was the release of a new Romney ad criticizing Obama’s outsourcing attacks as false.89 Coverage of Romney and Bain Capital increased on that day and even more on July 13, when approximately 50% of the mentions of Romney had to do with Bain Capital.

Coverage declined somewhat on July 14—in part due to the usual Saturday lull—which was when the Obama campaign released the “Firms” ad and Obama and Romney continued to joust over the Bain attacks.90 It picked up again on July 15 and 16 before tapering off. Several New York Times headlines convey the steady pace of stories: “Romney Ad Faults Tone of Obama Campaign’s Attacks,” “When Did Romney Step Back from Bain? It’s Complicated, Filings Suggest,” and “After Weekend of Attacks, Romney Campaign Shields Itself with Polls.”

There is no question that this week of news coverage was generally unfavorable to Romney. As Figure 5.3 showed, the coverage was net negative for Romney during most of this period, improving only at the very end before dropping off on July 20.91 Moreover, news coverage of Romney and Bain was more negative than coverage of Romney overall. Coverage of Obama also became more negative. During July 17–19, coverage of Obama was even more negative than Romney’s. This was when Romney began a counteroffensive that included attacks on Obama for his “you didn’t build that” comment and for alleged cronyism. Then Bain Capital receded from the news.

This episode illustrates the challenges of focusing on Romney’s experience at Bain Capital. Clearly the Boston Globe story plus the Obama campaign’s attacks generated negative press for Romney initially. But as Romney struck back, both candidates had to deal with negative press—not because the press itself was critical but because it was covering what the candidates were saying, and what they were saying was largely critical of each other. Obama could not escape attacks any more than Romney could. Thus the Romney campaign, even as it seemed to be back on its heels, helped neutralize the Bain attacks, at least in terms of the tenor of news coverage.

Perhaps, however, all of these attacks and counterattacks did not neutralize each other. Perhaps the attacks on Romney’s record at Bain Capital were more effective. If that were true, public opinion should have moved in Obama’s favor. But it did not. As Figure 5.4 shows, if anything, Romney’s standing in the polls increased in July, narrowing Obama’s lead. Among the potentially persuadable voters we discussed earlier, there was also no clear shift against Romney during this time: indeed he received more support from those voters at the end of July than at the beginning.

Other measures of what voters thought about the candidates showed few trends. For example, at the beginning of May, the percentage of voters with a favorable view of Romney was 40% in YouGov polling. This briefly increased to 44% at the beginning of July, even though this was at the peak of Obama’s advertising. But during July, the trend line was flat. At the end of July, the percentage of voters with a favorable view of Romney was 40%—the same as three months prior.92 The RAND data, which began July 11 and allow a fine-grained day-by-day analysis, also showed no change in the candidates’ standing during the period when Bain Capital was so much in the news. In fact, if anything, Obama’s lead over Romney was slightly higher before the Boston Globe story broke than it was a week later, after all of the controversy. Some small number of people may have shifted their preferences during this time, but if so, the shifts canceled one another out and produced steady poll numbers overall.

We can drill down even further to assessments of Romney’s specific qualities. During the summer months, there was no trend in whether people thought Romney was “likable” or whether he “says what he believes” (versus “what he thinks people want to hear”). And the indicators most intimately connected to the Bain attacks—which measured Romney’s empathy—were similarly stable. We noted earlier that Romney faced the disadvantage that many Republican presidential candidates have faced: the perception that he was less concerned about the poor and middle class than about the wealthy. The Bain attacks seemed designed to magnify this perception. But no such thing occurred. The percentage of the voters who thought that “cares about people like me” described Romney somewhat or very well was 42% in early January, 38% in early April, 42% in June, and 40% at the end of July. The same stability was evident in the other items: cares about the poor, cares about the middle class, and cares about the wealthy.

The relationships among these different items were also fairly stable. Earlier we noted two relationships in particular: between believing Romney was personally wealthy and believing he cared about the wealthy, and between believing Romney cared about the wealthy and believing he did not care as much about the middle class or “people like me.” The coverage of Romney’s time at Bain Capital could have made those relationships stronger. Certainly the Obama campaign was trying to connect Romney’s wealth and business practices (outsourcing, profits earned from Bain Capital deals, Cayman Islands tax havens, etc.) to an alleged lack of concern about the middle class (“If Romney wins, the middle class loses”). But these relationships were relatively static.93

The coverage of Romney and Bain Capital could have mattered in another way: by strengthening the connection between vote intentions and beliefs about Romney’s wealth and empathy. This, too, would be a plausible goal for Obama and Priorities USA. Given that Obama had the advantage in this domain—more people believed he cared about the middle class than believed that about Romney—the Obama campaign would have wanted this domain to become more central in people’s decision about which candidate to vote for. Many academic studies have documented how political campaigns can “prime” certain decision-making criteria in this way.94 We calculated the difference between evaluations of Obama and Romney on each of these empathy dimensions (cares about people like me, cares about the poor, cares about the middle class, cares about the wealthy, is personally wealthy) and looked to see if these differences became more strongly related to vote intention in July. They did not (see the appendix to this chapter).

Did the Early Ads Matter?

So far we have described a summer of feverish campaigning that produced mostly stable trends in public opinion overall. There are two possible explanations for this stability. One is that the ads and other electioneering simply had no effect on anyone—they were, to be frank, a waste of money. The other possibility is that the Obama ads shifted votes to Obama in places where Obama out-advertised Romney and, simultaneously, Romney ads shifted votes to Romney in places where he out-advertised Obama. The result was no net advantage for either candidate. If so, the money spent on ads was not wasted. Quite to the contrary, it was vital. If one candidate had stood down, the polls might have shifted to the other candidate.

Sorting out which of these two patterns was underlying the stability requires investigating the relationship between candidate advertising and people’s vote intentions. To identify whether and how the ads might have mattered, we could exploit variation in when and where Obama or Romney was airing more ads. Because both candidates focused their advertising in battleground states, with few national advertising buys, and because Obama and Romney each had the lead in different media markets at different times, this variation existed: voters outside the battleground states saw few if any ads, while voters in the battleground states may have seen more Obama ads or more Romney ads, depending on where they lived and when they were surveyed.

The advertising data that we analyzed were obtained from the Nielsen Company and were measured in “gross rating points” (GRPs), a metric that captures the expected penetration of ads in a given market.95 To measure advertising advantage, we calculated the difference in each candidate’s total GRPs for each day. We included not only candidate ads but ads paid for by the RNC—the Democratic National Committee (DNC) did not air its own advertisements in the presidential race—and by the major independent groups supporting one of the candidates: for Obama, Priorities USA Action; for Romney, Restore Our Future, American Crossroads, Crossroads GPS, and Americans for Prosperity.

Figure 5.7.

Difference in advertising GRPs during June and July in selected markets.