The House of Commons

The House of CommonsPREVIEW

The term ‘parliament’ comes from the French parler, meaning ‘to speak’. Parliament is therefore basically a debating chamber. Some even refer to it as the ‘debating chamber of the nation’. But Parliament is much more than a place where people talk. It is also the place where laws are made and where the government (or the executive) confronts the opposition. Parliament is the UK’s supreme law-making body, and it is the key institution within its ‘parliamentary’ system of government. This means that the government does not operate separately from Parliament, but rather it governs in and through Parliament.

And yet, the decline of Parliament has been a recurrent theme in the UK, dating back to the 19th century. Parliament, it seems, has lost power to many bodies – disciplined political parties, the executive, lobbyists and pressure groups of various kinds, the mass media, a ‘federal’ EU, and so on. For some, Parliament has simply become an irrelevance, a sideshow to the real business of running the country. But this image is an unbalanced one. Parliament does make a difference, even though it attracts less and less press coverage. The question is: does it make enough difference? A weak Parliament has implications for the effectiveness of democracy, the accountability of government, the quality of public policy – the list goes on. Although Parliament has changed significantly in recent years, there is continued and growing pressure for more radical change. How effective is Parliament? And how could it be made more effective?

CONTENTS

• The role of Parliament

- The make-up of Parliament

- Functions of Parliament

- Parliamentary government

• The effectiveness of Parliament

- Theories of parliamentary power

- Parliament and government

• Reforming Parliament

- Commons reform under Blair

- Commons reform under Brown

- Commons reform under Cameron and Clegg

- Reforming the Lords

THE MAKE-UP OF PARLIAMENT

Although Parliament is often treated as a single institution, it is in fact composed of three parts:

The House of Commons

The House of Commons

The House of Lords

The House of Lords

The monarchy (or, in legal terms, the ‘Crown in Parliament’).

The monarchy (or, in legal terms, the ‘Crown in Parliament’).

The House of Commons

Composition

The composition of the House of Commons is easy to describe as there is only one basis for membership: all Members of Parliament (MPs) win their seats in the same way. The composition of the House of Commons is as follows:

• The House of Commons consists of 650 MPs (this number is not fixed but varies each time changes are made to parliamentary constituencies. The intended reduction in the number of MPs to 600 was delayed by the calling of the 2017 general election).

• Each MP is elected by a single-member parliamentary constituency using the ‘first-past-the-post’ voting system (see p. 65).

• MPs are (almost always) representatives of a party and are subject to a system of party discipline.

• Most MPs are categorised as backbenchers, while a minority are categorised as frontbenchers.

Backbencher: An MP who does not hold a ministerial or ‘shadow’ ministerial post; so-called because they tend to sit on the back benches.

Frontbencher: An MP who holds a ministerial or ‘shadow’ ministerial post, and who usually sits on the front benches.

Powers

The House of Commons is politically and legally the dominant chamber of Parliament. This applies to such an extent that the Commons is sometimes taken to be identical with Parliament itself. However, a distinction should be made between the formal powers of the House, enshrined in law and constitutional theory, and its political significance (discussed later).

The two key powers of the House of Commons are:

• The House of Commons has supreme legislative power. In theory, the Commons can make, unmake and amend any law it wishes, with the Lords only being able to delay these laws. The legal sovereignty of Parliament is thus exercised in practice by the Commons (subject only to the higher authority of EU laws and treaties).

• The House of Commons alone can remove the government of the day. This power is based on the convention of collective ministerial responsibility (see p. 244). A government that is defeated in the Commons on a major issue or a matter of confidence is obliged to resign or to call a general election.

House of Lords

Composition

The composition of the House of Lords is both complex and controversial. It is complex because there are three distinct bases for membership of the House, meaning that there are four kinds of peers. It is controversial because none of these peers is elected. The current membership stems from the House of Lords Act 1999, which removed most (but not all) of the previously dominant hereditary peers, and from the 2005 Constitutional Reform Act, which removed the Law Lords from the House of Lords and set up a Supreme Court which came into existence in 2009.

The House of Lords consists of the following:

• Life peers. Life peers (as the title implies) are peers who are entitled to sit in the Lords for their own lifetimes. They are appointed under the Life Peerages Act 1958. Life peers are appointed by the prime minister, with recommendations also being made by opposition leaders. Since 2000, a number of so-called ‘people’s peers’ have been appointed on the basis of individual recommendations made to the House of Lords Appointments Commission (63 had been appointed by the end of 2014, although their lack of resemblance to ‘ordinary’ citizens has been a source of criticism). Life peers now dominate the work of the Lords. They account for the overwhelming majority of peers (688 out of a total of 804 peers (86 per cent) in April 2017).

• Hereditary peers. These are peers who hold inherited titles which also carry the right to sit in the House of Lords. In descending order of rank, they are dukes, marquises, earls, viscounts and barons, and their female equivalents. Once there were over 700 hereditary peers, but since 1999 only a maximum 92 are permitted to sit. The Earl Marshall and Lord Great Chamberlain remain by right, while the remainder are elected either by the hereditary peers in the ‘unreformed’ House of Lords or, as they die or are disqualified, by the parties.

• ‘Lords Spiritual’. These are the bishops and archbishops of the Church of England. They are collectively referred to as the ‘Lords Spiritual’ (as opposed to all other peers, the ‘Lords Temporal’). They are 26 in number, and they have traditionally been appointed by the prime minister on the basis of recommendations made by the Church of England.

The House of Lords’ legislative powers are set out in the Parliament Acts of 1911 and 1949. The Lords has the following powers:

• The Lords can delay bills passed by the House of Commons for up to one year. However, the Lords cannot delay ‘money bills ’ and, by the so-called Salisbury convention (also known as the Salisbury–Addison convention), the Lords cannot defeat measures that are outlined in the government’s election manifesto.

Money bill: A bill that contains significant financial measures, as determined by the Speaker of the House of Commons.

• The Lords possess some veto powers. These are powers that cannot be overridden by the Commons. They include:

• The extension to the life of Parliament – delays to general elections

• The sacking of senior judges, which can only be done with the consent of both Houses of Parliament

• The introduction of secondary, or delegated legislation.

The monarchy

The monarchy is often the ‘ignored’ part of Parliament. This is understandable because the role of the Queen is normally entirely ceremonial and symbolic. As a non-executive head of state, the monarch symbolises the authority of the Crown.

Head of state: The leading representative of a state, who personally embodies the state’s power and authority; a title of essentially symbolic significance, as opposed to the head of government.

The monarch is associated with Parliament in a number of ways:

• Appointing a government. The Queen chooses the prime minister who, in turn, appoints other members of the government. In practice, the Queen usually has little choice over this matter, as the leader of the largest party in the House of Commons is the only person who can command the confidence of Parliament.

• Opening and dismissing Parliament. The Queen opens Parliament through the State Opening at the beginning of the parliamentary year, usually in late October/ early November. At the request of the prime minister, she dismisses (or ‘dissolves’) Parliament in order to allow for a general election to be held.

• The Queen’s speech. This is a speech that is delivered at the beginning of each parliamentary session, which informs Parliament of the government’s legislative programme. The speech (known as the ‘gracious address’) is written by the prime minister. In July 2007, Gordon Brown initiated the practice of the prime minister pre-announcing draft proposals for the Queen’s Speech at the end of the previous parliamentary session.

• The Royal Assent. This is the final stage of the legislative process, when the Queen (or her representative) signs a bill to make it an Act. This, however, is a mere formality as, by convention, monarchs never refuse to grant the Royal Assent. In Walter Bagehot’s formulation, the monarchy is a ‘dignified’ rather than ‘effective’ institution.

FUNCTIONS OF PARLIAMENT

Parliament is sometimes classified as an ‘assembly’, a ‘legislature’ or a ‘deliberative body’. The truth is: it is all these things. Parliament has many functions within the political system. The key functions of Parliament are:

Legislation

Legislation

Representation

Representation

Scrutiny and oversight

Scrutiny and oversight

Recruitment and training of ministers

Recruitment and training of ministers

Legitimacy.

Legitimacy.

Legislation

Parliament makes laws. This is why it is classified as a legislature. Indeed, Parliament is the supreme legislature in the UK, in that it can make and unmake any law it wishes (subject to the higher authority of EU law), as expressed in the principle of parliamentary sovereignty (see p. 189). Parliament is not restricted by a codified constitution, and no other law-making body can challenge Parliament’s authority. Devolved assemblies, local authorities and ministers can only make laws because Parliament allows them to.

Legislature: The branch of government that has the power to make laws through the formal enactment of legislation (statutes).

However, Parliament’s effectiveness as a legislature has also been questioned:

• The bulk of Parliament’s time is spent considering the government’s legislative programme. Only a small number of bills, private member’s bills, are initiated by backbenchers, and these are only successful if they have government support.

Private member’s bill: A bill that is proposed by an MP who is not a member of the government, usually through an annual ballot.

• Party control of the House of Commons means that government bills are rarely defeated, and most amendments affect the details of legislation, not its major principles. It is more accurate to say that legislation is passed through Parliament rather than by Parliament.

• The Lords play a subordinate role in the legislative process. It is essentially a ‘revising chamber’; most of its time is spent ‘cleaning up’ bills not adequately scrutinised in the Commons.

A government bill has to go through the following parliamentary stages:

• Preparatory stages. Before bills are passed, their provisions may have been outlined in a White Paper or a Green Paper. Since 2002, most government bills have been published in draft for what is called prelegislative scrutiny, which is carried out by select committees (see p. 217).

• First reading. The bill is introduced to Parliament through the formal reading of its title and (usually) the setting of a date for its second reading. There is no debate or vote at this stage.

• Second reading. This is the first substantive stage. It involves a full debate that considers the principles (rather than the details) of the bill. It is the first stage at which the bill can be defeated.

• Committee stage. This is when the details of the bill are considered line by line. It is carried out by a public bill committee (formerly known as a standing committee), consisting of about 18 MPs, but it may be considered by a Committee of the Whole House. Most amendments are made at this stage, and new provisions can be included.

• Report stage. This is when the committee reports back to the full House of Commons on any changes made during the committee stage. The Commons may amend or reverse changes at the report stage.

• Third reading. This replicates the second reading in that it is a debate of the full chamber, enabling the House to take an overview of the bill in its amended state. No amendments may be made at this stage, and it is very unusual for bills to be defeated at the third reading.

• The ‘other place’. Major bills are considered first by the Commons, but other bills may start in the Lords. Once passed by one chamber, the bill goes through essentially the same process in what is referred to as the ‘other place’, before finally going to the monarch for the Royal Assent.

Representation

To represent means, in everyday language, to ‘portray’ or ‘make present’, as when a picture is said to represent a scene or person. As a political principle, representation (see p. 63) is a relationship through which an individual or group stands for, or acts on behalf of, a larger body of people. In modern politics, this relationship is seen to be forged through a process of election. This means that Parliament’s representative role is entirely carried out by its sole elected body, the House of Commons, and specifically by constituency MPs. MPs are therefore representatives in the sense that they ‘serve’ their constituents, a responsibility that typically falls most heavily on backbenchers, as they are not encumbered by ministerial or shadow ministerial responsibilities.

However, the effectiveness of parliamentary representation has also been criticised:

• As the House of Lords is unelected, it carries out no representative role and weakens the democratic responsiveness of Parliament (see ‘Debating … An elected second chamber’, p. 235).

• The ‘first-past-the-post’ electoral system undermines the effectiveness of representation in the House of Commons (see Chapter 3).

• There is no agreement as to how parliamentary representation is, or should be, carried out. In practice, there are a number of theories of representation.

• Delegation. A representative may be a delegate, in the sense that they act as a conduit conveying the views of others, without expressing their own views or opinions. Examples of delegation include sales representatives and ambassadors, but the notion of delegation has rarely been applied to MPs.

• Trusteeship. A representative may be a trustee, in the sense that they act on behalf of others, using their supposedly superior knowledge, better education or greater experience. This form of representation is sometimes called ‘Burkean representation’, as its classic expression is found in the speech that the Conservative philosopher and historian Edmund Burke (1729–97) gave to the electors of Bristol in 1774. He declared that, ‘Your representative owes you, not his industry alone, but his judgement; and he betrays, instead of serving you, if he sacrifices it to your opinion.’ Until the 1950s, it was widely held that MPs should think for themselves, using their own judgement, on the grounds that ordinary voters did not know their own best interests.

• Doctrine of the mandate. This is the most influential theory of representation in modern politics. It is based on the idea that, in winning an election, a party gains a mandate to carry out the policies on which it fought the election, the policies contained in its manifesto. This doctrine implies that it is political parties, rather than individual MPs, that discharge Parliament’s representative function. Such thinking provides a clear justification for party unity and party discipline. However, the idea that people vote according to the contents of party manifestos is difficult to sustain in practice, and the doctrine provides no clear guidance in relation to policies that are dissolved between elections.

• Descriptive representation. Sometimes called ‘characteristic representation’, this theory emphasises the importance to representation of people’s social characteristics and the groups to which they belong. It is primarily concerned to improve the representation of groups of people who have been historically under-represented in positions of power and influence in society – women, ethnic minorities, the working class, young people, and so on. It does this both in the belief that the views and interests of such groups will be more effectively represented and on the grounds that having a greater diversity of viewpoints will result in political bodies making better decisions for the common good (see ‘The social background of MPs’, p. 216).

Delegate: A person who is chosen to act for another on the basis of clear guidance or instructions; delegates do not think for themselves.

Trustee: A person who has formal (and usually legal) responsibility for another’s property or affairs.

Scrutiny and oversight

Parliament does not govern, but its role is to check or constrain the government of the day. Many therefore argue that Parliament’s most important function is to ‘call the government to account’, forcing ministers to explain their actions and justify their policies. It does this through scrutinising and overseeing what government does. This is the key to ensuring responsible government. In this role, Parliament acts as a ‘watchdog’, exposing any blunders or mistakes the government may make. Parliamentary oversight is underpinned by the conventions of individual responsibility (see p. 245) and collective responsibility.

Scrutiny: Examining something in a close or detailed way.

Responsible government: A government that is answerable or accountable to an elected assembly and, through it, to the people.

• Social class. MPs are predominantly middle class. Over four-fifths have a professional or business background, with the main professions being politics (23 per cent), business (22 per cent) and finance (15 per cent). The manual working class is significantly under-represented, even in the Labour party (10 per cent).

• Gender. Women continue to be under-represented in the Commons, but they have made substantial progress since the 1980s, when their numbers stood at only just over 3 per cent of MPs. The 2017 election saw the largest ever number of women MPs at 208 (32 per cent of the total). This increase was thanks largely to the 45 per cent of Labour MPs who are female.

• Ethnicity. Ethnic minorities remain under-represented. However, 2017 saw the highest number of non-white MPs being elected, at 52, or 8 per cent of the whole, up from 27 in 2010.

• Age. MPs are predominantly middle-aged: 70 per cent of them are between 40 and 59, with the average age in 2015 being 51.

• Education. MPs are better educated than most UK citizens. Over two-thirds are graduates. Also, 29 per cent of them have attended private schools, four times more than the population as a whole.

• Sexuality. There are 45 LGBT MPs (7 per cent), which is by some way higher than anywhere else in the world.

However, the effectiveness of Parliament in carrying out the scrutiny of government has also been questioned:

• As the majority of MPs in the House of Commons (normally) belong to the governing party, their primary role is to support the government of the day, not to criticise and embarrass it.

• Question Time is often weak and ineffective. Oral questions seldom produce detailed responses, and are used more to embarrass ministers than to subject them to careful scrutiny. Prime minister’s questions, in particular, often degenerates into a party-political battle between the prime minister and the leader of the opposition that generates more heat than light.

• Although select committees are widely seen as more effective than Question Time, they also have their disadvantages. These include that:

• The government has a majority on each of these committees (the committees reflect the composition of the House of Commons).

• Individual committee appointments are influenced by the whips, who ensure that loyal backbenchers sit on key committees, although committee chairs have been elected by the Commons since June 2010.

• Select committees have no executive power. At best, they can criticise government; they cannot change government policy.

• Question Time. The best known aspect of Question Time is Prime Minister’s Questions (PMQs), which takes place each Wednesday from 12.00 to 12.30. MPs ask one notified question of the prime minister and one (unscripted) supplementary question. PMQs are dominated by clashes between the prime minister and the leader of the opposition, who is able to ask four or five ‘supplementaries’. Question Time also extends to other ministers, forcing them to answer oral questions from MPs. Each department features in a four-week cycle.

• Select committees. Select committees scrutinise government policy (as opposed to public bill committees, which examine government legislation). There are 19 departmental select committees (DSCs), which shadow the work of each of the major government departments. They carry out inquiries and write reports, being able also to carry out question-and-answer sessions with ministers, civil servants and other witnesses, and to ask to see government papers.

• Debates and ministerial statements. Government policy can be examined through legislative debates and through emergency debates that are held at the discretion of the Speaker. Adjournment debates allow backbenchers to initiate debates at the end of the parliamentary day. Ministers are also required to make formal statements to Parliament on major policy issues.

• The opposition. The second largest party in the House of Commons is designated as ‘Her Majesty’s loyal opposition’. It is given privileges in debates, at Question Time and in the management of parliamentary business to help it carry out its role of opposing the government of the day. On ‘opposition days’ (sometimes called ‘supply days’), opposition parties choose the subject for debate and use these days as opportunities either to criticise government policy or to highlight alternative policies.

• Written questions and letters. Much information is provided to MPs and peers in answers to written questions (as opposed to oral questions in Question Time), and ministers must respond to letters they receive from MPs and peers.

Recruitment and training of ministers

Parliament acts as a major channel of political recruitment. In the UK, all ministers, from the prime minister downwards, must be either MPs or peers. Before they become frontbenchers, they ‘cut their teeth’ on the back benches. The advantage of this is that by participating in debates, asking parliamentary questions and sitting on committees, the ministers of the future learn their political trade. They gain an understanding of how government works and of how policy is developed.

However, the effectiveness of this recruitment and training role has also been questioned:

• Ministers are recruited from a limited pool of talent: mainly the MPs of the largest party in the House of Commons.

• Parliamentarians may acquire speechmaking skills and learn how to deliver sound bites, but they do not gain the bureaucratic or management skills to run a government department.

• Fewer and fewer ministers have experience of careers outside of politics.

Legitimacy

The final function of Parliament is to promote legitimacy. When governments govern through Parliament, their actions are more likely to be seen as ‘rightful’ and therefore to be obeyed. This occurs for two reasons:

• Parliament, in a sense, ‘stands for’ the public, being a representative assembly. When it approves a measure, this makes it feel as though the public has approved it.

• Parliamentary approval is based on the assumption that the government’s actions have been properly debated and scrutinised, with any weaknesses or problems being properly exposed.

However, Parliament’s ability to ensure legitimacy has also been criticised:

• Being non-elected, the House of Lords has no democratic legitimacy.

• Respect for Parliament has been undermined by scandals involving, for example, ‘cash for questions’ (MPs being paid for asking parliamentary questions) and ‘cash for peerages’.

PARLIAMENTARY GOVERNMENT

Not only does Parliament carry out a number of major functions within UK government, but it is also the lynchpin of the political system itself. The UK has a parliamentary system of government. This is why the UK system is often said to be based on a ‘Westminster model’ (see p. 19). But in what sense is the UK system of government ‘parliamentary’? And what does this imply about the role and significance of Parliament?

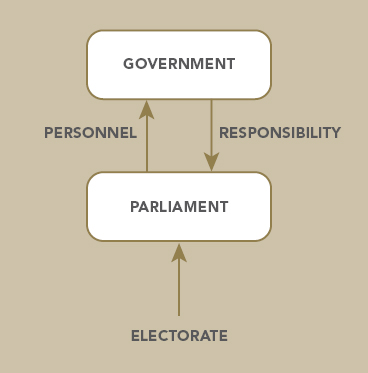

In a parliamentary system, government and Parliament form an interlocking whole, based on a ‘fusion’ of power between the executive and the legislative branches of government (see Figure 8.1). Government is ‘parliamentary’ in the sense that it is drawn from, and accountable to, Parliament. This implies that Parliament (or, in practice, the House of Commons) has the power to bring the government down. In theory, this should make Parliament the dominant institution – governments should only be able to act as Parliament allows. This, indeed, did briefly happen in the UK during Parliament’s ‘golden age’ in the 1840s. During this period, Parliament regularly defeated the government, meaning that policy was genuinely determined by the views of MPs. However, the development of modern, disciplined political parties changed all this. The majority of MPs in the House of Commons came to see their role not as criticising the government but as defending it. The primary function of Parliament therefore shifted from making government accountable to maintaining it in power. This is why parliamentary government is often associated with the problem of executive domination, or what Lord Hailsham called ‘elective dictatorship’ (see p. 194).

Figure 8.1 Parliamentary government

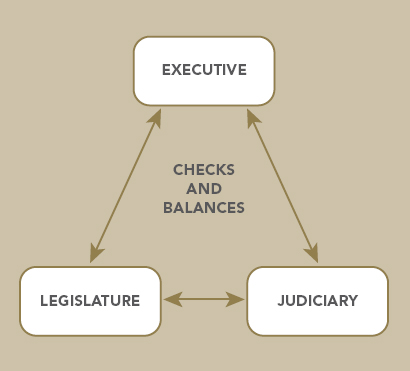

Figure 8.2 The separation of powers

Key concept … PARLIAMENTARY GOVERNMENT

A parliamentary system of government is one in which government governs in and through Parliament. It is based on a ‘fusion’ between the legislative and executive branches of government. Parliament and government are therefore overlapping and interlocking institutions. This violates the doctrine of the separation of powers in a crucial way.

The chief features of parliamentary government are as follows:

• Governments are formed as a result of parliamentary elections, based on the strength of party representation in the Commons

• The personnel of government are drawn from Parliament, usually from the leaders of the largest party in the House of Commons

• Government is responsible to Parliament, in the sense that it rests on the confidence of the House of Commons and can be removed through defeat on a ‘vote of confidence’

• Government can ‘dissolve’ Parliament, meaning that electoral terms are flexible within a five-year limit (although this has been restricted by the introduction of fixed-term Parliaments)

• Government has a collective ‘face’, in that it is based on the principle of cabinet government (see p. 248) rather than personal leadership (as in a presidency)

• As a parliamentary officer, the prime minister is the head of government but not the head of state; these two roles are strictly separate.

Differences between ...

Parliamentary and Presidential Government

Presidential systems, on the other hand, may produce more powerful and independent legislatures or parliaments. This is because the doctrine of the separation of powers (see Figure 8.2 and p. 279) ensures that the government and Parliament are formally independent from one another and separately elected. In the USA, for instance, this gives Congress a degree of independence from the presidency that makes it probably the most powerful legislature in the modern world (see ‘The US Congress’, p. 231).

THE EFFECTIVENESS OF PARLIAMENT

THEORIES OF PARLIAMENTARY POWER

Parliamentary power has been interpreted in three different ways:

The Westminster model

This is the classic view of Parliament as the lynchpin of the UK system of government. It implies that Parliament delivers both representative government (it is the mouthpiece of the people) and responsible government (it holds the executive to account). In this view, Parliament has significant policy influence. (This model was perhaps only realistic during the ‘golden age’ of Parliament.)

The Whitehall model

This model suggests that political and constitutional power have shifted firmly from Parliament to the executive. Parliament is executive-dominated, and acts as little more than a ‘rubber stamp’ for government policy. In this view, Parliament has no meaningful policy influence. (This model was widely accepted until the 1980s.)

The transformative model

This model provides an alternative to the ‘Westminster’ and the ‘Whitehall’ models of parliamentary power. It accepts that Parliament is no longer a policy-making body, but neither is it a simple irrelevance. In this view, Parliament can transform policy but only by reacting to executive initiatives. (This model has been generally accepted in recent years, not least because of recent changes within the parliamentary system.)

PARLIAMENT AND GOVERNMENT

How effective is Parliament in practice? There is no fixed relationship between Parliament and government. The principles of parliamentary government establish a framework within which both Parliament and government work, but, as was pointed out earlier, this does not determine the distribution of power between them. Parliament has huge potential power, but its actual ability to influence policy and constrain government may be very limited.

Four main factors affect Parliament’s relationship to government:

Extent of party unity

Extent of party unity

Size of majority

Size of majority

Single party or coalition government

Single party or coalition government

Impact of the Lords.

Impact of the Lords.

Party unity and its decline

Party unity is the key to understanding the relationship between Parliament and government. It is the main lever that the executive uses to control Parliament in general and the House of Commons in particular. The decline of Parliament stems from the growth of party unity in the final decades of the 19th century. By 1900, 90 per cent of votes in the Commons were party votes (that is, votes in which at least 90 per cent of MPs voted with their party). This was a direct consequence of the extension of the franchise and the recognition by MPs that they needed the support of a party machine in order to win elections. During much of the 20th century, MPs appeared to be mere ‘lobby fodder ’.

Lobby fodder: MPs who speak and vote (in the lobbies) as their parties dictate without thinking for themselves.

• The whipping system. The whips are often seen as ‘the stick’ that maintains party discipline. The job of the whips is to make sure that MPs know how their parties want them to vote, indicated by debates being underlined once, twice or three times (obedience is essential in the case of a ‘three-line’ whip). The whips:

• Advise the leadership about party morale

• Reward loyalty by, for example, advising on promotions

• Punish disloyalty, ultimately by ‘withdrawing’ the whip (suspending membership of the parliamentary party).

• The ‘payroll’ vote. Ministers and shadow ministers must support government policy because of the convention of collective responsibility. This ensures the loyalty of between 100 and 110 frontbench government MPs.

• Promotion prospects. This is the ‘carrot’ of party unity. Most backbench MPs wish to become ministers, and loyalty is the best way of advancing their careers because it gains them the support of ministers and the whips.

• Ideological unity. Most MPs, on most occasions, do not need to be forced to ‘toe a party line’. As long-standing party members and political activists, they ‘believe’ in their party or government.

This created the impression that government had nothing to fear from Parliament. The government could always rely on its loyal troops in the House of Commons to approve its legislative programme and to maintain it in power, creating an ‘elective dictatorship’.

However, this image of mindless party discipline is now outdated. Party unity reached its peak in the 1950s and early 1960s when backbench revolts all but died out. Since then, backbench power has been on the rise as party discipline has relaxed.

Backbench revolt: Disunity by backbench MPs, who vote against their party on a ‘whipped’ vote.

Notable examples of party disunity include:

• Labour governments of Harold Wilson and James Callaghan, 1974–79. During this period, 45 per cent of Labour MPs voted against the government at some stage, with 40 of them doing so on more than 50 occasions.

• Conservative governments under Margaret Thatcher 1979–90. Although the frequency of backbench revolts abated during this period, it was the failure of a sufficient number of MPs to support her in the 1990 party leadership election that caused Thatcher’s downfall.

• Conservative governments under John Major, 1990–97. This period was characterised by dramatic clashes between the Major government and a small but determined group of Eurosceptic backbenchers (see p. 226).

• Labour governments under Tony Blair and Gordon Brown, 2001–10. During Blair’s second and third terms, Labour backbenchers rebelled against the government on over 20 per cent of all divisions. Some of these rebellions were very large. On 64 occasions, 40 or more Labour MPs voted against the government, including major rebellions on high-profile issues, such as foundation hospitals (involving 65 MPs), university ‘top-up’ fees (72), the Iraq War (139) and the replacement of Trident nuclear submarines (94).

• Conservative–Liberal Democrat coalition under David Cameron, 2010–15. This was the most rebellious parliament since 1945. In its first four years, Coalition rebellions occurred in 37 per cent of divisions, with no fewer than 159 Conservatives (52 per cent of the parliamentary party) and 42 Liberal Democrats (74 per cent of the parliamentary party) defying the party whip at one time or another. The major issue over which backbenchers revolted was relations with the European Union.

• Conservative government under David Cameron, 2015–16. Significant backbench pressure forced the Cameron government into making U-turns on at least 24 policies. Among the policies abandoned were the proposal that all schools should become academies, cuts to tax credits, and pension tax relief reform. In addition, the Cameron government was defeated three times, most memorably in March 2016 on the proposed deregulation of Sunday trading rules.

• Conservative government under Theresa May, 2016–17. The May government continued the practice of Cameron, in seeking to head off backbench restiveness by modifying or reversing policies before they provoked open revolt and possibly led to parliamentary defeat. This is a tactic commonly employed by governments with slim majorities, which cannot afford to stand up to significant backbench pressure. Examples of policy ‘rethinks’ in these circumstances under May included the commitment in January 2017 to publish a White Paper on the government’s Brexit plan just days after ministers had ruled out this step; the promise in February 2017 to give MPs and peers a vote on the Brexit deal negotiated with Brussels before it is due to come into effect; and, most embarassingly, the withdrawal of the National Insurance hike for the self-employed one week after it had been announced in the March 2017 Budget.

Explaining declining party unity

Why has party unity declined? There are long-term and short-term answers to this question. The long-term answers are:

• MPs are generally better educated than they were in the 1950s and 1960s, coming overwhelmingly from professional middle-class backgrounds. This has made them more critical and independently minded.

• More MPs are now ‘career politicians’. As politics is their only career, they have the time and resources to take political issues more seriously. Many MPs used to have ‘second’ jobs, usually in business or as lawyers.

• Since the 1990s, the process of ‘modernisation’ in, first, the Labour Party and later the Conservative Party has focused on a bid for centrist support and alienated MPs in each party who hold more ‘traditional’ views (Labour left-wingers and Conservative right-wingers).

EUROSCEPTICS IN REVOLT

The rise of Euroscepticism on the Conservative back benches in recent decades has profoundly affected the balance between Parliament and the executive. This was first evident during 1992–3, when prime minister John Major sought parliamentary approval for signing the Maastricht treaty (Treaty on European Union). A small but determined group of so-called Maastricht rebels were able to exert disproportionate influence due to Major’s slim majority, which stood at 22 in 1992 but fell steadily following by-election defeats. Despite negotiating opt-outs for the UK on aspects of the Maastricht treaty related to monetary union and the Social Chapter, the government came close to defeat on three occasions. A hard core of rebels even defied Major when he threatened an early dissolution of Parliament, eight of them later having the whip withdrawn from them (another resigned the whip in sympathy). These divisions were to cast a dark shadow over the rest of Major’s premiership and contributed to the Conservatives’ 1997 election defeat (see p. 96) by damaging both the party’s image and the prime minister’s public standing.

Major’s 1997 defeat nevertheless marked the point at which Euroscepticism ceased to be the concern of but a handful of Conservative MPs and gained progressively wider influence, reflecting a trend of rising hostility towards ‘Europe’ among Conservative constituency associations since the 1980s. Nevertheless, when he was appointed Conservative leader in December 2005, David Cameron warned the party to ‘stop banging on about Europe’, arguing that splits over Europe had contributed to the party’s extended period in opposition. On becoming prime minister in 2010, Cameron therefore sought to neutralise the European issue in the party by persuading his coalition partners, the Liberal Democrats, to agree to hold a referendum in the event of a new EU treaty, effectively blocking any further European integration.

However, backbench Conservative Euroscepticism soon re-emerged on a scale that dwarfed anything that had confronted Major. No fewer than 81 Conservatives (27 per cent of the party’s MPs) defied a three-line whip in October 2011 to vote in favour of a motion calling for a referendum on membership of the EU. Having initially firmly rejected this demand, in January 2013 Cameron carried out a dramatic U-turn and pledged to hold an ‘in/out’ referendum on EU membership, should the Conservatives win the 2015 general election. Although Cameron feared being drawn into an intractable battle with backbench Eurosceptics that would sap his authority, the promise of a referendum was more a strategic concession on Cameron’s part, than the action of a prime minister who had run out of options. With an effective majority of 83, and the likely support of Labour on the issue, Cameron did not face the realistic possibility of a Commons defeat over Europe.

The short-term factors include the public standing of the government and the likelihood of it winning re-election, the personal authority of the prime minister and the radicalism of the government’s legislative programme. This helps to explain, for example, the difference between Blair’s first government (1997–2001) and his second and third governments (2001–07). In the latter period, Blair’s personal standing had dropped as a result of the Iraq War, the government’s majority and its poll ratings had fallen, and divisive issues such as anti-terror legislation, welfare reform and university ‘top-up’ fees had become more prominent.

Size of majority

If the party system is the single most important factor affecting the performance of Parliament, the second is that the governing party has traditionally had majority control of the Commons. This has occurred not because of voting patterns (no party has won a majority of votes in a general election since 1935), but because of the tendency of the ‘first-past-the-post’ voting system to over-represent large parties (see Chapter 3). This has happened very reliably: for example, until 2010 only one general election since 1945 (February 1974) had failed to produce a single-party majority government.

However, the size of a government’s majority has also been crucial. The larger the government’s majority, the weaker backbenchers will usually be. For instance, with a majority of 178 after the 1997 election it would have taken 90 Labour MPs to defeat the Blair government (assuming that all opposition MPs voted against the government). Once Blair’s majority had fallen to 65 after the 2005 election, this could be done by just 34 Labour MPs. The contrast between small and large majorities can be stark. The 1974–79 Labour government, which had at best a majority of 4 and was for some time a minority government, was defeated in the House of Commons on no fewer than 41 occasions. However, with landslide majorities in 1997 (178) and in 2001 (167), the Blair government suffered no defeats in the House of Commons in its first two terms.

Minority government: A government that does not have overall majority support in the assembly or parliament; minority governments are usually formed by single parties that are unable, or unwilling, to form coalitions.

The first – and, almost certainly, the most significant – implication of the formation of the Conservative–Liberal Democrat coalition in 2010 was that it led to the creation of a majority government despite the election of a ‘hung’ Parliament. The Coalition’s ‘official’ majority of 77 seats amounted, in practice, to an effective majority of 83, due to the fact that some Northern Ireland MPs never take up their seats. This helped to reduce the number of government defeats during the 2010–15 Parliament, although a number of other devices were also used for this purpose, including calling free votes on government bills. The Cameron government thus suffered just six defeats in five years, compared with the 1976–79 Callaghan government, which ended up with no majority, which was defeated 34 times. Although the Conservatives gained an overall majority in 2015, starting with a working majority of just 12 left the Cameron and May governments unusually vulnerable to backbench pressure.

Single-party or coalition government

There is a general expectation that coalition government will rejuvenate Parliament. This is based on the belief that a coalition will radically alter the dynamics of executive–Parliament relations. Single-party majority governments (the norm in the UK since 1945) were able to control the Commons so long as they maintained party unity, and, if their majorities were substantial, even backbench revolts had only a marginal significance. By contrast, coalitions are forced to manage the Commons not simply by maintaining unity in a single party, but by establishing and maintaining unity across two or more parties. The process of interparty debate, negotiation and conciliation that this inevitably involves is widely believed to make the legislature an important focus of policy debate. In short, coalition government means that the support of backbench MPs for government policy cannot simply be taken for granted.

In the case of the 2010–15 Conservative–Liberal Democrat Coalition, there was little evidence of such tendencies during its first year in office, possibly because MPs in both parties were keen to show that the Coalition could work and, being unfamiliar with coalition arrangements, were fearful of the consequences of dissent. However, this started to change, particularly after the failure of the AV referendum in May 2011, with backbench revolts becoming more common and, in some cases, spectacular. This eventually made the 2010–15 Parliament the most rebellious since the Second World War. Although there was a growing pattern of Liberal Democrat backbench disloyalty, fuelled, in part, by the desire to maintain the party’s distinctive identity within the Coalition, the most rebellious MPs tended to be right-wing Eurosceptical Conservatives.

However, in other respects, coalition government may be a recipe for a weak Parliament. This is because the process of interparty consultation and negotiation that coalition government inevitably involves is more likely to take place within the executive itself, and often at its highest levels, rather than within Parliament. In fact, most coalitions involve the centralisation, not the decentralisation, of decision-making processes (as discussed in Chapter 9). Furthermore, the image of a Conservative-led coalition government being pushed around by disgruntled backbenchers is, at best, a partial one. For one thing, the Coalition experienced relatively little difficulty in getting parliamentary approval for its radical programme of spending cuts, and even succeeded in getting deeply controversial NHS reforms onto the statute book.

Impact of the Lords

Although the House of Lords is clearly the subordinate chamber of Parliament in terms of its formal powers, it is often a more effective check on the executive than the Commons. Executive control of the Commons is normally secured through a combination of the voting system (creating a single-party majority) and the party system. By contrast, in the Lords:

• Party unity is more relaxed. This occurs because, being non-elected, peers do not need a party machine to remain in post. Once appointed, peers are there for life. This robs the government of its ability to discipline peers and so ‘enforce’ the whip.

• There was no guarantee of majority control. In fact, until 2000, the dominance of hereditary peers meant that the Conservatives effectively enjoyed an in-built majority in the Lords. Labour governments, on the other hand, confronted a consistently hostile second chamber. The House of Lords’ checking power was therefore used in a highly partisan way.

These factors were dramatically demonstrated by the fact that, while the Blair government suffered no defeats in the Commons during its first two terms in office, it was defeated in the Lords on no fewer than 353 occasions. By contrast, the average number of Lords’ defeats per session during the Conservative governments of 1979–97 was just over 13. However, the level of opposition that the Blair government encountered in the House of Lords was untypical, even by the standards of previous Labour governments. It involved fierce clashes over terrorism legislation, with a range of other measures being either amended or delayed as a result of Lords’ pressure, including the outlawing of hunting with dogs, the introduction of foundation hospitals, restrictions on jury trial and changes to pension regulations. As an indication of its continuing assertiveness the 2010–15 Conservative-led coalition was defeated on over 100 occasions. The ‘partially reformed’ House of Lords therefore appears to have become a more significant check on the government than the ‘traditional’ House of Lords had been. Why has this happened?

The greater impact of the Lords can be explained in a number of ways:

• No majority party in the Lords. In the ‘partially reformed’ Lords, there is a balance between Conservative and Labour representation, the parties having 256 and 204 peers respectively, out of a total of 809 (in 2017). All governments therefore have to seek support from other parties and from crossbenchers in order to get legislation passed (even the Coalition was supported by only 42 per cent of peers).

• Greater legitimacy. The removal of most of the hereditary peers has encouraged the members of the House of Lords to believe that they have a right to assert their authority. As peers now feel that the Lords is more properly constituted, they are more willing to challenge the government, especially over controversial proposals and legislation.

• Landslide majorities in the Commons. Some peers have argued that they have a particular duty to check the government of the day in the event of landslide majorities in the Commons that render the first chamber almost powerless (as in 1997 and 2001).

• The politics of the Parliament Acts. Although the Parliament Acts allow the Commons to overrule the Lords, their use is very time-consuming as it means that bills get regularly passed back and forth between the two Houses of Parliament (a process called ‘parliamentary ping-pong’). Governments are therefore often more anxious to reach a compromise with the Lords than to ‘steamroller’ a bill through using the 1949 Parliament Act. (This Act has, in fact, only been invoked on four occasions.)

FOR Effective coalitions. Much criticism of coalition government stems from misconceptions about how they operate elsewhere, often sustained by unrepresentative examples (Italy). Coalition governments are commonplace across continental Europe and, in most cases, they are stable and cohesive. This particularly occurs as political parties adjust to a culture of partnership and compromise. There is no reason why UK parties cannot adjust to such a culture, enabling them to form effective coalitions. Broad, popular government. As they are formed by two or more parties, coalitions represent a wider range of views and interests than do single-party governments. Similarly, there is a greater likelihood that the combined electoral support for all the coalition partners will exceed 50 per cent. This means that coalitions, unlike most single-party governments in the UK, can genuinely claim to have a popular mandate. End of adversarialism. Single-party government tends to operate in the context of a two-party system, in which politics degenerates into an ongoing electoral battle between government and opposition. Instead of incessant disagreement and conflict, coalitions allow for the emergence of the ‘new politics’. Released from adversarialism (so-called ‘yaa-boo’ politics), parties are able to form alliances and work together on matters of common concern. Wider pool of talent. One of the drawbacks of single-party government is that ministers can only be selected from the ranks of a single party’s MPs or peers. Coalition governments, by contrast, can access a wider range of talent, drawing on the expertise and experience of two or more parties. Coalitions therefore come closer to the ideal of a ‘government of all the talents’. |

AGAINST Weak government. Coalition governments cannot easily guarantee parliamentary approval for their programme of policies. Much of the government’s energies have to be devoted to resolving tensions and conflicts between coalition partners. More seriously, internal disagreement, in government or in Parliament, can lead to paralysis, making it perhaps impossible for a coalition government to exercise bold policy leadership. Unstable government. Coalition governments, generally, do not last as long as single-party governments. They are fragile because the defection of one coalition partner will usually bring the government down, and coalition parties are encouraged to threaten such defections in the hope of exerting greater influence. More frequent general elections, and more regular changes in government, risk creating a general climate of instability. Democracy undermined. Deals that are done after the election inevitably mean that coalition parties abandon some of the policies on which they fought the election and accept some policies they had criticised. Not only may some voters therefore feel betrayed, but no one has a chance to accept or reject the coalition’s eventual programme for government. There is also no guarantee that parties’ influence within the coalition will reflect their electoral strength. Confused ideological direction. Whereas individual parties attempt to develop coherent policy programmes based on clear ideological visions, coalition governments’ policy programmes are often unclear or inconsistent. They are shaped not by a single ideological vision but by the attempt to reconcile two (or more) contrasting visions. |

REFORMING PARLIAMENT

Debate about the reform of Parliament has been going on for well over 100 years. This debate has been fuelled, most of all, by anxiety about the growth of executive power and Parliament’s declining ability effectively to check the government of the day. However, support for parliamentary reform has by no means been universal. Some argue that the present arrangements have the advantage that they guarantee strong government, sometimes seen as one of the key advantages of the Westminster model. Nevertheless, as with the larger issue of constitutional reform (discussed in Chapter 6), there has been growing pressure in recent years to reform and strengthen Parliament. The following sections examine the reforms that have taken place in recent years in the House of Commons and the House of Lords. They also consider how each of these chambers could be further strengthened.

Strong government: A situation in which government can govern, in the sense of translating its legislative programme into public policy.

COMMONS REFORM UNDER BLAIR

The main reforms of Parliament introduced under Blair, between 1997 and 2007, concern the Lords rather than the Commons. However, a number of changes did take place in the Commons, although their net impact was modest, especially in view of the government’s large majorities in 1997 and 2001, and its emphasis on tight party discipline, particularly in its early years (seen as ‘control freakery’). The main changes were:

• Liaison Committee scrutiny. Introduced in 2002, this allows for twice-yearly appearances of the prime minister before the Liaison Committee of the House of Commons, which is mainly composed of the chairs of the departmental select committees (DSCs).The prime minister is thus subject to scrutiny by some of the most senior, experienced and expert backbenchers in the House of Commons.

• Freedom of Information Act 2000. Freedom of information was not a parliamentary reform as such. Rather, it was an attempt to widen the public’s access to information that is held by a wide range of public bodies, helping in particular to ensure open government. Nevertheless, the Act has strengthened parliamentary scrutiny by giving MPs and peers easier access to government information.

Open government: A free flow of information from government to representative bodies, the mass media and the electorate, based on the public’s ‘right to know’.

• Wider constitutional reforms. These, once again, are not reforms of Parliament, but they are reforms that have important implications for Parliament. The most significant ones in this respect were devolution, the introduction of the Human Rights Act (HRA) and the wider use of referendums. Devolution has meant that responsibility for domestic legislation in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland is now in the hands of devolved bodies, as opposed to Parliament (see Chapter 11). The HRA has helped to transfer responsibility for protecting individual rights from Parliament to the courts, as these rights now, in a sense, ‘belong’ to citizens (see Chapter10). Referendums have given the people, rather than Parliament, final control over a range of constitutional reforms (see Chapter 3). The net impact of wider constitutional changes under Blair was therefore to marginalise Parliament, rather than strengthen it.

COMMONS REFORM UNDER BROWN

On taking over as prime minister, Gordon Brown moved to give up or modify a number of powers that used to belong exclusively to the prime minister or the executive. In the main, this involved strengthening Parliament by improving the government’s need to consult with, or gain approval from, the House of Commons. Such moves would have brought Parliament more closely into line with the oversight and confirmation powers of the US Congress.

Parliament, and more specifically the Commons, would be consulted on the exercise of a variety of powers. These included the power to declare war, dissolve Parliament, recall Parliament, ratify treaties, and choose bishops and appoint judges. However, apart from the acceptance that Parliament’s right to be consulted before major military operations take place should be regarded as a constitutional convention, these proposals came to nothing.

The US Congress is a bicameral legislature, composed of the 435-member House of Representatives (lower chamber) and the 100-member Senate (higher or second chamber). Unlike Parliament, the chambers have equal legislative powers and both are elected (see ‘Elections in the USA’, p. 91). Congress is widely seen as the most powerful legislature in the world. It genuinely makes policy, whereas Parliament is a reactive and policy-influencing body. That said, most policy is initiated by the executive, so in the USA it is true to say that ‘the president proposes and Congress disposes’.

Congress is powerful for three main reasons:

• The US Constitution allocates Congress an impressive range of formal powers. These include the power to declare war, the ability to override a presidential veto on legislation and the power to impeach the president. The Senate has a range of further powers, notably to confirm presidential appointments (e.g. cabinet members and Supreme Court judges) and to ratify treaties.

• The president cannot count on controlling Congress through party unity because the two are separately elected. This means both that the opposition party may control one or both chambers of Congress, and that party unity is weaker than in Parliament. The primary loyalty of Congressmen and women and of Senators is to the ‘folks back home’ (their voters), rather than to their party.

• Congress has a powerful system of standing committees, which exert significant influence over US government departments and their budgets. These are the ‘powerhouse’ of Congress. The system of departmental select committees (DSCs) in the UK is largely modelled on congressional standing committees, but they are significantly weaker in practice.

COMMONS REFORM UNDER CAMERON AND CLEGG

The formation of the Conservative–Liberal Democrat coalition in 2010 led to the emergence of a bold and extensive programme of parliamentary reform. This was largely a consequence of the participation of the Liberal Democrats, the major party most deeply and consistently committed to political and constitutional reform. In general, the proposed Commons reforms sought either to strengthen government’s accountability to Parliament or to expand popular participation in the workings of Parliament. These reforms included the following:

• Fixed-term Parliaments. By trying to prevent prime ministers from calling general elections at a time most favourable to their party, fixed-term Parliaments were intended to reduce the size of government majorities and make changes of the party in power more frequent. Both tendencies were thought likely to enhance the influence of Parliament.

• Referendum on AV. Although rejected in 2011, AV promised to boost representation for ‘third’ parties such as the Liberal Democrats, and could have been expected to lead to more ‘hung’ Parliaments.

• Recall of MPs. This proposal was much delayed and eventually resulted in legislation more modest than originally intended. Under this, a recall petition can be triggered if an MP is sentenced to a prison term or suspended from the Commons for at least 21 sitting days. A by-election would then follow if the petition is signed by at least 10 per cent of eligible voters. This is intended to strengthen the representative function of the House of Commons.

• Public initiated bills. The public was given the ability to suggest topics for debate in Parliament through e-petitions that secure at least 100,000 signatures, which are then passed for consideration to the backbench business committee.

• Public reading stage. A ‘public reading stage’ was to be introduced for bills, giving the public an opportunity to comment on proposed legislation online. In the event, only a limited number of pilot public readings were introduced during the 2010–15 Parliament.

• Backbench business committee. Created in 2010, this select committee determines, on behalf of backbenchers, the business before the House for approximately one day a week. In addition to e-petition proposals, this includes selecting Topical Debates that last for one and a half hours.

However, it is by no means clear that such a reform programme would lead to a meaningful shift in the balance of power between Parliament and the executive. For example, in making general elections less frequent, five-year, fixed-term Parliaments may erode, rather than strengthen, the democratic legitimacy of Parliament, weakening its capacity to ‘speak for the nation’. Similarly, the opportunities these proposals created for private citizens to initiate bills, or to comment on bills, will not change the fact that Parliament primarily exists to consider the government’s legislative programme and that this is a process essentially controlled by the government itself.

REFORMING THE LORDS

The greatest attention in recent years in reforming Parliament has fallen on the Lords rather than the Commons. This is because the defects of the ‘unreformed’ Lords were so serious and so pressing. The most obvious of these were that:

• The majority of peers (if not of working peers) sat in the House of Lords on the basis of heredity.

• The Lords exhibited a strong and consistent bias in favour of the Conservative Party.

The fact that, despite this, major reform has been so long delayed is evidence of how difficult it is to reform the Lords. The major obstacles to reform have traditionally been the Conservative Party (concerned to introduce reform only to prevent more radical reform, as in the case of the Life Peerages Act 1958) and the Lords itself. Any attempt to abolish or reform the Lords would be likely to stimulate such a battle with the Commons that the government’s entire legislative programme would be put at threat. Moreover, Labour was often divided over the issue. Whereas some Labour MPs wished to abolish the Lords altogether, others favoured its replacement by a fully elected second chamber, with others even being happy with the status quo for fear of creating a stronger check on any future Labour government. Nevertheless, the Blair government began a phased process of reform in 1999.

‘Stage one’ reform of the Lords

In planning to reform the House of Lords, the Blair government learned the lessons of previous, unsuccessful attempts at reform. In particular, it recognised that, while there was general agreement about the central weaknesses of the Lords, there was substantial disagreement about what should replace it. Should the Lords be reformed or abolished? Should a reformed second chamber be wholly appointed, wholly elected or a mixture of the two? If the composition of the second chamber were to be altered, should its powers also change, and if so how? The solution was to introduce reform in two stages:

• Stage one. This would involve the removal of hereditary peers, without any further changes to the composition and powers of the chamber.

• Stage two. This would involve the replacement of the House of Lords by a revised second chamber.

The advantage of this approach was that difficult and divisive questions about the composition and powers of the second chamber could be put to one side while reforming energies focused on the ‘easier’ problem: ending the hereditary principle. Reform was duly brought about through the House of Lords Act 1999. To ease the passage of this bill, the government agreed to a compromise whereby a proportion of hereditary peers survived until stage-two reform took place. The number of hereditary peers was thus reduced from 777 to a maximum of 92.

However, stage two has proved to be far more difficult to deliver. In the first place, this reflected a declining appetite within the then Labour government to press ahead with further reform. The removal of most of the hereditary peers and the appointment of a large number of new Labour life peers had quickly put an end to Conservative dominance in the Lords. Furthermore, the new spirit of assertiveness in the partially reformed Lords made some ministers anxious about the prospect of a partially or wholly elected second chamber. Second, disagreement about the nature of any replacement chamber has continued.

The most concerted attempt to deliver stage two of Lords reform to date occurred during the 2010–15 Coalition. One of the key agreements under which the Conservative–Liberal Democrat coalition was formed was to bring forward proposals for a wholly or mainly elected second chamber on the basis of proportional representation. The cross-party committee set up for this purpose was chaired by Nick Clegg and was charged with developing a draft bill by December 2010. The fact that the draft bill did not emerge until May 2011 was a further indication of the difficulty of making progress on this issue. The key features of the proposals were that the new chamber would have 300 members, 80 per cent of whom will be elected using the single transferable vote system and who would serve for a single 15-year term. However, in common with the other attempts to make progress with ‘stage two’ of the reform of the Lords, this one also failed, when, facing stiff opposition from Conservative backbenchers, the legislation was abandoned in August 2012.

Key concept … BICAMERALISM

Bicameralism is the theory or practice of breaking up legislative power through the creation of two chambers. However, a distinction can be drawn between partial bicameralism and full bicameralism:

• Partial bicameralism is when the legislature has two chambers but these are clearly unequal, either because the second chamber has restricted popular authority or because it has reduced legislative power. The UK Parliament is a good example of partial (or deformed) bicameralism.

• Full bicameralism exists when there are two co-equal legislative chambers, each able to check the other. The US Congress is a good (if rare) example of full bicameralism.

FOR Democratic legitimacy. A second chamber, like all policy-making institutions, must be based on popular consent delivered through competitive elections. In a democracy, this is the only basis for legitimate rule. Appointed members simply do not have democratic legitimacy. Wider representation. Two elected chambers would widen the basis for representation. This could happen through the use of different electoral systems, different electoral terms and dates, and through different constituencies. This would significantly strengthen the democratic process. Better legislation. The non-elected basis of the House of Lords restricts its role to that of a ‘revising chamber’, concerned mainly with ‘cleaning up’ bills. Popular authority would encourage the second chamber to exercise greater powers of legislative oversight and scrutiny. Checking the Commons. Only an elected chamber can properly check another elected chamber. While the House of Commons alone has popular authority, the second chamber will also defer to the first chamber. Full bicameralism requires two co-equal chambers. Ending executive tyranny. The executive dominates Parliament largely through its majority control of the Commons. While this persists, the only way of properly checking government power is through a democratic or more powerful second chamber, preferably elected by PR. |

AGAINST Specialist knowledge. The advantage of an appointed second chamber is that its members, like life peers, can be chosen on the basis of their experience, expertise and specialist knowledge. Elected politicians may be experts only in the arts of public speaking and campaigning. Gridlocked government. Two co-equal chambers would be a recipe for government paralysis through institutionalised rivalry both between the chambers and between the executive and Parliament. This is most likely to occur if the two chambers are elected at different times or on the basis of different electoral systems. Complementary chambers. The advantage of having two chambers is that they can carry out different roles and functions. This can be seen in the benefits of the Lords’ role as a revising chamber, complementing the House of Commons. Only one chamber needs to express popular authority. Dangers of partisanship. Any elected chamber is going to be dominated, like the House of Commons, by party ‘hacks’, who rely on a party to get elected and to be re-elected. An appointed second chamber would, by contrast, have reduced partisanship, allowing peers to think for themselves. Descriptive representation. Elected peers may have popular authority but it is very difficult to make sure that they resemble the larger society, as the make-up of the Commons demonstrates. This can better be done through a structured process of appointment that takes account of group representation. |

In 2015, following a humiliating defeat by the Lords over planned cuts to tax credits, Cameron proposed a more modest and narrowly focused reform of the second chamber. Under plans devised by Lord Strathclyde, the Lords would have been stripped of the ability to veto statutory instruments, their power being reduced to the capacity to ask the Commons to ‘think again’ about proposed legislation. However, the proposal was shelved shortly after Theresa May took over as prime minister, both because it was unclear whether the reform was workable and because the government could not afford to pick a battle with the Lords with Brexit-related matters looming.

The future second chamber?

Much of the debate about Lords reform is about the composition of the second chamber with support being expressed for three different options: an appointed second chamber, an elected second chamber or some combination of the two. Nevertheless, the question of composition cannot be considered separately from the issue of powers. The restricted powers of the current House of Lords have usually been explained in terms of its non-elected status. Any largely or wholly elected second chamber could reasonably demand, and expect to be given, wider power if not equality with the first chamber.

Supporters of an elected second chamber tend to emphasise two key benefits. First, they stress the benefits of democracy, arguing that the only legitimate basis for exercising political power is success in free and fair elections. Second, they emphasise the benefits of full bicameralism, viewing a more powerful second chamber with popular authority as a way to combat ‘elective dictatorship’. By contrast, supporters of an appointed or nominated second chamber tend to stress the following two benefits. The first is that an appointed chamber could (rather like the present House of Lords) have greater expertise and specialist knowledge than the first chamber. The second is that partial bicameralism has undoubted benefits, in that it makes clashes between the two chambers less likely and does not lead to confusion about the location of popular authority. Those who back a mixture of elected and appointed members tend to suggest that such a solution offers the best of both worlds – a measure of democratic legitimacy but also expertise and specialist knowledge. However, any such solution can also be criticised for containing the worst of both worlds as well as for leading to confusion through creating two (or possibly more) classes of peer.

SHORT QUESTIONS:

1 What are the powers of the House of Commons?

2 What are the powers of the House of Lords?

3 Outline two functions of Parliament.

4 Outline the functions of the House of Commons.

5 Outline the functions of the House of Lords.

6 Briefly explain two features of parliamentary government.

7 Briefly explain two features of presidential government.

8 Define the principle of parliamentary sovereignty.

MEDIUM QUESTIONS:

9 In which ways does the composition of the House of Commons differ from that of the House of Lords?

10 What are the main functions of Parliament?

11 In which ways is Parliament representative?

12 Why has the UK system of government been considered to be parliamentary?

13 In which ways is Parliament sovereign?

14 How does parliamentary government differ from presidential government?

15 Explain three ways in which Parliament carries out its scrutinising role.

16 Why has it proved difficult to reform the House of Lords?

EXTENDED QUESTIONS:

17 To what extent does the House of Commons have greater power and influence than the House of Lords?

18 How effective is Parliament in carrying out its representative role?

19 How effective is Parliament in checking executive power?

20 How well does Parliament carry out its functions?

21 Has the UK Parliament become an irrelevant institution?

22 How, and to what extent, has the influence of the House of Commons changed in recent years?

23 Should the UK have a fully elected second chamber?

24 To what extent did coalition government alter the relationship between Parliament and the executive?