When you have completed this chapter you should be able to demonstrate an understanding of the following:

• the project control cycle, including planning, monitoring achievement, identifying variances and taking corrective action;

• the nature of and purposes for which project information is gathered;

• how to collect and present progress information;

• the reporting cycle;

• how to take corrective action.

Chapter 1 described the typical stages of a project that implements an information system. There we stressed the importance of controlling the project to ensure that it conforms to the plan. In Chapter 2, we explained the way in which the plan for a particular project is created.

This chapter explores the means by which a project is monitored and controlled so that it broadly fulfils its plan. The mechanism for this is the project control cycle.

The project control cycle involves the following sequence of steps:

a. producing a plan for the project to follow;

b. monitoring progress by collecting information about project performance;

c. comparing actual progress with the planned progress;

d. identifying variations from the plan;

e. applying corrective action if necessary.

Corrective action would usually involve changes to parts of the plan. These changes would have to be communicated to the project team and, where necessary, to stakeholders who might be affected by the changes.

Steps (b) to (e) are repeated to continue the control cycle, until the project is completed or abandoned.

Imagine a ship’s voyage across the Channel from Dover to Calais as your project. The plan would involve following a certain route, aiming to arrive in Calais at a certain time. As the voyage progressed, the navigator would check the ship’s progress against the planned course. If there was a difference, he or she could then decide that a change of speed or an alteration of course was necessary – this would be corrective action. The process would, of course, continue until the ship arrived at its destination. Without this control cycle, the ship could continue on a fixed course and speed, and would be very unlikely to arrive at the planned destination or at the expected arrival time.

Monitoring progress is less straightforward in an IT project than in the ship example. The first question, which we tackle in the next section, is how to identify things that should be monitored. We usually know what the final objective of the project is, but how do we know how well we are progressing towards that objective?

The most obvious thing to monitor is the progress in creating deliverables and other, intermediate, project products, and in reaching milestones or deadlines. Difficulties arise when you want to monitor progress of things that are partially complete. The simple solution is to break the products and deliverables into smaller components that can be assessed as complete at shorter and more frequent intervals of time – for example, software can be broken down into smaller, relatively self-contained modules.

Where this is difficult, an alternative is to assess the percentage completion of an activity or deliverable. This can be problematic. If someone is building a wall, it is easy to see when it is half finished, but, particularly in the case of software, most project products are less obviously visible than with a wall.

The project manager often finds that an activity which appears to be completed has in fact delivered a defective product that requires the activity to be reopened to carry out remedial work, which delays project progress. Hence, project control depends on effective quality processes that check the quality of the methods used to carry out each activity and the quality of the deliverables of each activity. This is covered in more detail in Chapter 5 on quality issues.

In Chapter 6, we describe size or effort drivers. These allow us to measure the size of the job to be done. In the case of building the wall, the number of bricks would be an obvious size driver: the bigger the wall, the more bricks it will need. The size/effort driver can be used to monitor progress. For example, if we know that the bricklayer will need to lay 200 bricks to build the wall but only 50 have been laid so far, then we can assume that the job is about 25 per cent complete.

In the end, the project’s deliverables need to be useful to the people who will have to interact with them. The deliverables also need to enable the hoped-for benefits that motivated the project sponsors to invest in the project. The project will have been planned with this in mind. During the implementation of the project, changes may be made – such as reducing the functionality to be produced – and the impact of this on the benefits of the project must be assessed. This will need the approval of the sponsor.

The use of resources also needs to be monitored, which in IT projects are mostly ‘human resources’ or staff time. Also, financial expenditure should be carefully monitored. In the scenario in Activity 3.1 below, allowing the installer to stay in an hotel between installations in the same region may save on travelling time (and fuel costs) and speed up the installation rate, but it would need to be balanced against the additional cost of accommodation. Surprisingly, however, financial expenditure on human resources is not always strictly monitored in IT projects if the project team are permanent employees in an IT department and therefore viewed as overheads.

ACTIVITY 3.1

There are 20 boatyards and marinas where Water Holiday Company customers collect and return their hired boats. As part of the new integrated booking system, online customers will be emailed an e-ticket, containing a barcode, which they will be expected to present at the relevant marina at the start of their holiday with evidence of their identity. The e-ticket requires new IT equipment to be installed at each boatyard/marina, and some additional training will be needed in other features of the new system – for example, recording the non-availability of boats for maintenance reasons.

It has been estimated that the installer will, on average, need a day to travel to a marina, install the new equipment and show local staff how it is used. Twenty days (or four working weeks) have been allocated for the installation of all the equipment.

However, at the end of the first week only three marinas have in fact been visited.

a. How long is it likely that the installation programme will now take?

b. What difference to the figure you have produced in (a) might be made by the following circumstances?

• The installer started two days late because some items of equipment had not been delivered.

• The installer started with the marinas furthest afield, and needed extra time to travel to the area and back.

As well as scope – essentially the amount of functionality being produced – being reduced to meet a deadline, functionality to be delivered could increase because new requirements are discovered. If these additions to the work are not monitored and controlled, costs and delivery time will be affected.

Thus time, cost and the scope of deliverables need to be balanced. For example, it may be possible to accelerate the progress of a late project by employing more staff, but this would increase the project cost. On the other hand, it may be possible to meet the deadline within the budgeted cost by reducing features in the application to be delivered – see Section 1.7.2, where timeboxing was described.

The systems that bring these different types of project information together for consideration are often referred to as dashboards.

Monitoring involves collecting information about actual project progress. This enables the comparison of actual project performance with what was envisaged in a plan. Formal monitoring methods include the use of written reports, email and progress meetings. The frequency, format and content of these communications should be laid down at the start of a project in the project management plan (see Section 1.8.1).

Formal monitoring establishes routines so that people periodically focus on progress and commit themselves in writing. However, preparing reports can be seen as an unproductive overhead. Staff need to be convinced of its value. Thus, timesheets can be effective in establishing the staff effort expended on distinct aspects of projects, but staff need to be persuaded to fill them in conscientiously.

Many phrases can describe informal monitoring: keeping one’s ear to the ground; management by walking about; open door policy. All these make the manager aware of what team members are experiencing. Project managers need ways of maintaining good informal lines of communication with all project staff. This often allows problems to be resolved before they would otherwise appear in a progress report. However, a pitfall to avoid is the alienation of team members by over-supervision.

There is no point in monitoring without control. This is done through the reporting cycle. Monitoring processes identify shortfalls in the progress of the project, that is variances between what has been planned and what has actually happened. To remedy variances, control needs to be applied to the project to bring it back on course. For example, staff might be transferred from non-critical work to critical activities that have fallen behind.

The reporting cycle defined in the project management plan identifies who should be producing progress reports, with what frequency and to whom they are sent. Remember that reporting is an overhead. Reports should therefore be concise, relevant and circulated only to those who need them. However, more concise reports require greater effort by the writer in order to save the time of the readers. As someone once apologised: ‘I am sorry this report is so long; I didn’t have time to write a shorter one.’

The reporting structure refers to the people involved in a project at various management levels. Generally, progress reporting starts at the level at which work is actually done and progresses up through a hierarchy.

In an IT context, team leaders gather progress information from their team and report up to their project manager. This may be done directly or through a project support office or other intermediary. The project manager then reports to the person or group that has been entrusted with overall responsibility for the project. This might be a project sponsor or executive supported by a project board, project management board or steering committee. This group could include representatives of the managers of the development team and the users as well as the project sponsor, who, as the provider of finance, inevitably has a decisive influence. They, not the project manager, have the authority to change the objectives of the project. They could allocate more resources to the project or reduce the scope of deliverables.

The report to the project board or steering committee is sometimes referred to as a highlight report. The intervals at which the reports are produced and the topics they report should meet the needs of the recipients and the importance of the information conveyed. It is important to obtain formal agreement with the reporting procedures laid down in the project management plan from all the major parties involved.

As far as the project manager is concerned, there are two aspects of reporting: the reports they receive from those who actually do the work, and the reports they write conveying progress information to higher management, including, most importantly, project sponsors. Reporting does not have to involve physical meetings, especially where projects are geographically dispersed.

The team leader might be able to obtain the progress information they need from team members without having a group meeting. However, meetings are not just about a team leader communicating with individual team members, but team members talking to one another. Where obstacles to progress have to be removed, a meeting can be a very efficient tool.

These are usually attended by team members, the team leader and possibly the project manager. On small projects with a single team, the project manager and team leader roles may be merged. A weekly frequency is usually appropriate (in some Agile projects there may even be daily ‘stand-up’ meetings). A report from the team leader to the project manager will be prepared. A typical agenda would include the following:

• each individual team member’s progress against their plans;

• reasons for variances;

• expected progress – which looks forward to what each team member is going to do;

• possible future problems – which may involve reviewing the risks recorded in the project risk register (see Chapter 7) that could affect this part of the project.

It is important that all those attending have a reason for attending and a contribution to make. These meetings are often referred to as checkpoint meetings and the progress report produced in this case is a checkpoint report. (In an Agile project, a backlog list identifying tasks completed and those still to be done would be updated.) As issues are identified, they may be recorded in an issues log, which will be updated as they are resolved.

The project manager receives the reports from team leaders and produces a summary report (sometimes called a highlight report) for the sponsors of the project. Where there are a number of teams, each with its own leader working in parallel on a project, the project manager may well hold project coordination meetings with the team leaders to review and remove obstacles to project progress.

The summary report typically includes the following information:

• details of the progress of the project against the plan;

• current milestones achieved;

• deliverables completed;

• resource usage;

• reasons for any deviation from the plan;

• new issues and unresolved issues;

• changes to risk assessments;

• plans for the next period and products to be delivered;

• graphical representations of progress information.

You will recall from Chapter 1 that the project sponsor is the individual responsible for safeguarding the interests of the client. The project sponsor might work through meetings of a steering committee or project management board. These meetings will be attended by designated representatives of users, suppliers and other stakeholders, with the project manager in attendance and with secretarial support perhaps provided by a project support office or project management office. The structure and responsibilities of the various roles in this structure are covered in Chapter 8.

The frequency of meetings will have been agreed and recorded in the project management plan. The exact timing depends on the project size: larger projects may have fewer and less frequent top-level meetings, but more meetings of managers at intermediate levels. Meetings can be timed to coincide with significant project events such as the completion of a particular project phase or stage (that is, a milestone) or other, external, triggers such as requirements for financial approvals.

Items for the agenda are similar to those for team meetings. The summary report described above, from the project manager to the board, is circulated prior to the meeting. The board is authorised to decide upon any necessary corrective action arising from progress information. This is fed back down the reporting chain and thus completes the reporting cycle.

Organisations sometimes group projects into programmes, where a number of projects all contribute to a set of over-arching objectives (see Chapter 8). In these cases a programme board may be set up, to which individual project boards would report. These boards would have less frequent, less detailed meetings related to programme management, but with essentially a similar agenda to those of the project boards. These would have more of a business focus than a project focus.

Here we will examine how corrective action can be applied in a controlled way. The project manager’s role is to manage on a day-to-day basis, applying minor corrections as required. However, corrections of a more major nature will need to be referred to higher authority.

This is the reason for allocating a tolerance within which the project manager has authority to make changes or apply corrective action. For example, you, as a project manager, may be allocated 10 per cent tolerance on time and cost on a project worth £100,000 and lasting 25 weeks. This means you are authorised to agree to changes incurring additional costs up to £10,000 or an overrun of two and a half weeks (see Chapter 4 on change control). If a situation occurred in which the project was expected to overrun by more than two and a half weeks, this would be an exception. In this case, you would need to prepare an exception report for submission to a special meeting of the project board, or equivalent. This exception report would describe a number of options designed to correct the overrun and the board would decide how to proceed.

Tolerance and contingency pools are sometimes distinguished. Tolerances can be assigned to individual activities within the project. The contingency pool is a set of resources that is controlled by the project manager and can be allocated at the discretion of the project manager wherever additional resources are needed. However, if the contingency is used to buy resources in one place, less will be available for other emergencies. These resources may be added to where activities are completed early and developer time is freed up. Where activities can be completed early, the opportunity should be seized as this will release staff to deal with unanticipated delays elsewhere.

An exception report typically includes the following information:

• background;

• reasons why the exception arose;

• options;

• exception plans showing how the project plans need to be amended in order to implement the suggested options;

• amended business case;

• recommendations.

When members of the project board (or equivalent) scrutinise the exception report, they will be particularly concerned to ensure that the business case for the project will be preserved: that is, that the costs of the project will not exceed the value of its eventual benefits. If the board are satisfied with the exception report, the project manager is given authority to proceed using the chosen option and its associated exception plan. Chapter 4, on change, describes an alternative approach where changes need to be made to systems that are already operational.

Where monitoring reveals a shortfall in the expected progress, control is applied to bring the project back on track. There are a number of standard control strategies, which may or may not require an exception report. These are considered below.

This may work to solve a short-term problem or to meet a critical deadline. It will fail if over-used. Staff will become tired, stressed and then demotivated. If overtime is paid, then project costs increase, but not by as much as with the next option.

Resources in this context mean people. Adding more staff can increase the amount of work done, but usually decreases productivity. The introduction of more staff involves a period of induction while they familiarise themselves with the work. The current staff may be involved in this process and the overall effect could be to delay progress. An exception report and plan are needed if the additional costs go beyond the tolerances agreed for the project.

Although some project activities have consumed more staff effort or taken longer than planned, others may have taken less effort or time. Internal movement of staff from tasks completed early can make up for delays elsewhere without extra cost. Some may unkindly attribute this to poor planning, but the truth is that there will always be uncertainty about exactly how long tasks will take.

Changes to deadlines need negotiation, usually through the exception reporting process described above. Extending the deadline is often seen as weak management or as allowing the project to get out of control, but can be the most sensible option. It increases costs, as staff are allocated to the project for longer; however, sometimes the reason a project is late is that it has not been possible to assign all the staff originally planned, and so budget may not be a problem. The negative impact of delay can be reduced by delivering more valuable functionality on time (or even earlier) while postponing less valuable functions.

This is an attractive option which also needs negotiation with management and drafting of an exception plan. Deliverables may be removed from the plan or delayed until after the planned project end date. This does not affect the originally planned cost or duration of the project, but the value of benefits to the user may be reduced. As noted in Chapter 1, this is the preferred solution of some Agile project management approaches.

If no acceptable alternative can be found, this may be the only remaining sensible action. Terminating the project would be justified if it is clear that the remaining costs of the project will exceed the projected value of its benefits when delivered. Despite this, terminating the project may be politically unacceptable.

ACTIVITY 3.2

In the Water Holiday Company integration project, activity G, ‘Write software’ (see Figure 2.11), has been outsourced to an external software development company, XYZ. XYZ find that the task ‘Code provisional booking function’ is going to take five weeks rather than four. Their contract with the Water Holiday Company states that they will have to pay a penalty of £500 for each week of delay in delivering the software.

The options considered by XYZ are:

a. Be a week late and pay the penalty.

b. Split the ‘Code provisional booking function’ into two subcomponents requiring three weeks of work each and bring in an extra developer to work in parallel with the one currently assigned to this function. Software developers cost £400 a week.

c. Get the Water Holiday Company to accept a delivered system on time but with some functionality missing. The supplier will agree to provide updates to implement the missing functionality at no extra charge, although this will require an additional week of coding work at a later date.

Which would be the most cost-effective option for the software supplier?

In Chapter 2 we produced a Gantt chart showing the activities needed in a project and the relationships between those activities. It also showed the resources – mainly developers – allocated to each activity. In some cases an activity could be delayed as a developer was not available to do the work. When the project is put into action, activities may in fact be longer or shorter than planned, and the staff available may change. The question tackled here is how project managers can get a picture of the current state of this complex ever-changing situation so that they can intervene to keep it on target.

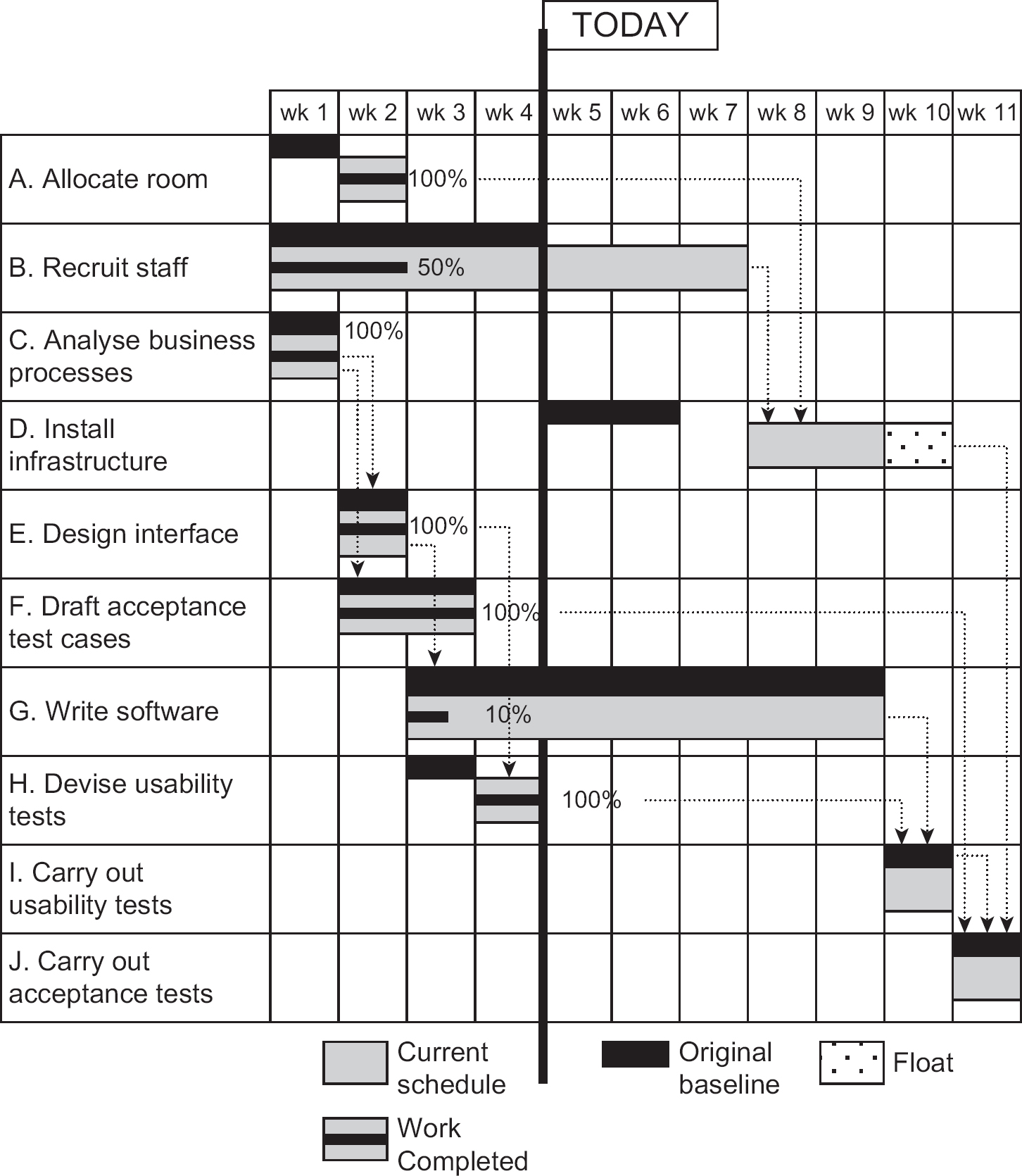

Progress information can be shown on a Gantt chart by putting a bar through an activity box showing the estimated percentage completion. Figure 3.1 shows the Gantt chart that was produced in Chapter 2 (Figure 2.13), updated to show the actual situation at the end of week 3 of the project. At this point the following information could be reported:

| Activity reference | Name | Progress |

| A | Allocate room | Started a week late, completed a week later |

| B | Recruit staff | Reported as 50% complete, but should be more like 75% at this point. An extra day is added to planned duration |

| C | Analyse business processes | Completed on time |

| D | Install infrastructure | This started a week late because of the late finish of activity A |

| E | Design interface | Completed on time |

| F | Draft acceptance test cases | Completed on time |

| G | Write software | 10% completed |

| H | Devise usability tests | Start delayed by one week |

We need to compare the current situation with the original plan. We said above that the project is always in a state of flux. To cope with this, we take a snapshot of the details on the Gantt chart. We call this a baseline. There can be several of these, but an important baseline will be the agreed schedule at the start of the project, before any work. This is shown in Figure 3.1 by the black boxes. The copy of the baseline is then marked up to show actual progress; for instance, to show that task A should have started in week 1, but actually started in week 2. We now have a baseline plus the changes to the baseline.

To reduce the amount of detail, at an agreed point, we can create a new baseline of the Gantt chart where all the activities are shown as starting and finishing on the new times, and the fact that these are changes is removed. This is effectively a new plan that can be used to record progress for the next period of the project.

Figure 3.1 A Gantt chart that has been updated with actual progress

ACTIVITY 3.3

In week 4, the following actions take place:

a. Activity B. Recruit staff. There have been difficulties with finding qualified staff and effectively no progress has been made. It is reported that two further weeks, in addition to those already scheduled, will be needed.

b. Activity G. Write software. There is a discrepancy in the requirements which means that progress has been held up for the week. Currently, it is hoped that the developers will be able to catch up over the next few weeks.

c. Activity H. Devise usability tests. This has now been completed.

Update the Gantt chart in Figure 3.1 to take account of these changes.

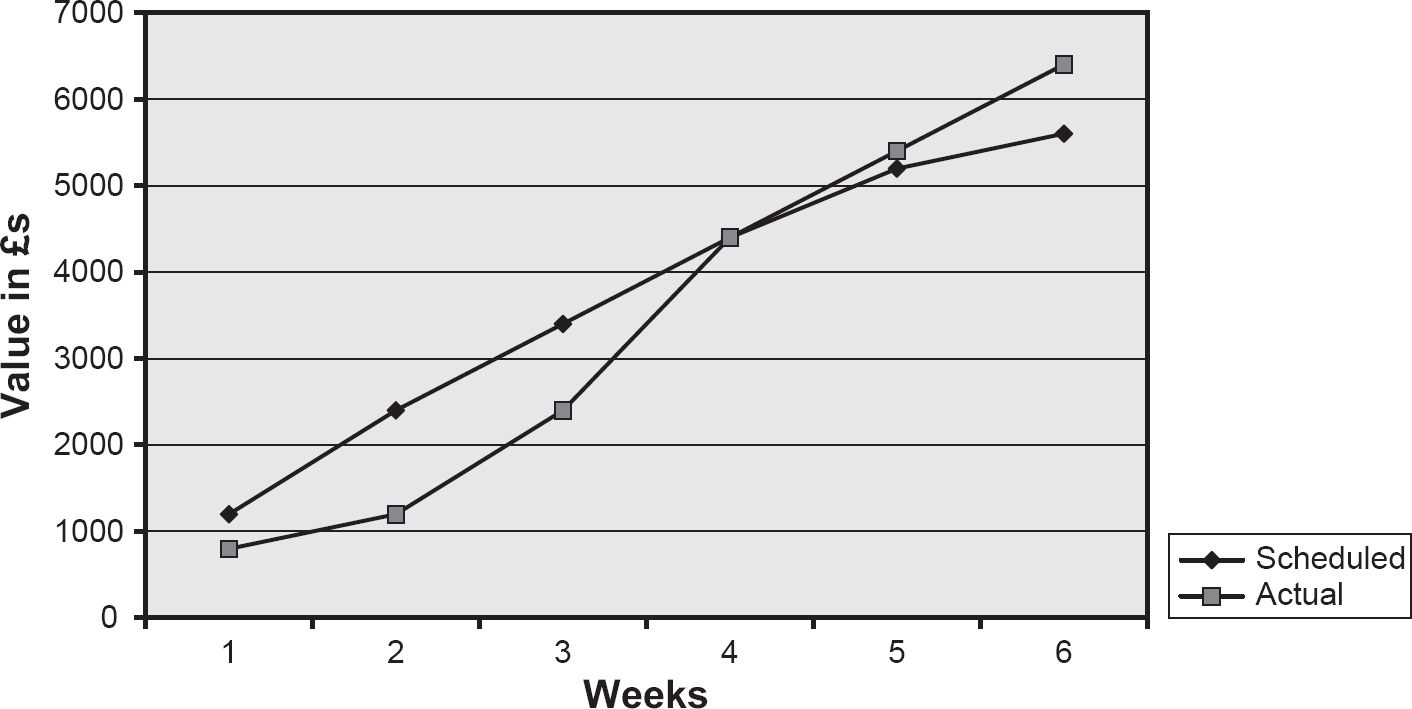

A cumulative resource chart can be used to present resource usage details (see Figure 3.2). This is sometimes called an S-curve chart, because the pattern of activity is that a project starts with a relatively low number of staff at the planning and requirements gathering stage. As the project progresses, more and more staff are needed as the development and implementation activities multiply. The demand for staff then decreases as the implementation proceeds – for example, software developers are not needed full-time once they have constructed their software components. This pattern of activity – a low demand for staff time which gradually builds up and then declines – leads to a cumulative resource chart where the line seems to have an approximate S-shape.

These charts normally have two sets of data points: one showing the expenditure that was planned and the other the actual expenditure for comparison.

Figure 3.2 A cumulative resource chart

This is a convenient visual representation of project progress suitable to show to management.

Figure 3.2 shows that for most of the project we were under-spending, but there has recently been a surge in expenditure, so that currently we have spent more than planned. However, we do not know whether this is due to poor productivity or whether we have actually produced more than was scheduled – work may have been completed early, leading to some expenditure also being incurred earlier.

The traditional S-curve chart does not show any of the following:

• whether the project is ahead or behind schedule;

• whether the project is getting value for money;

• whether problems are over or just beginning.

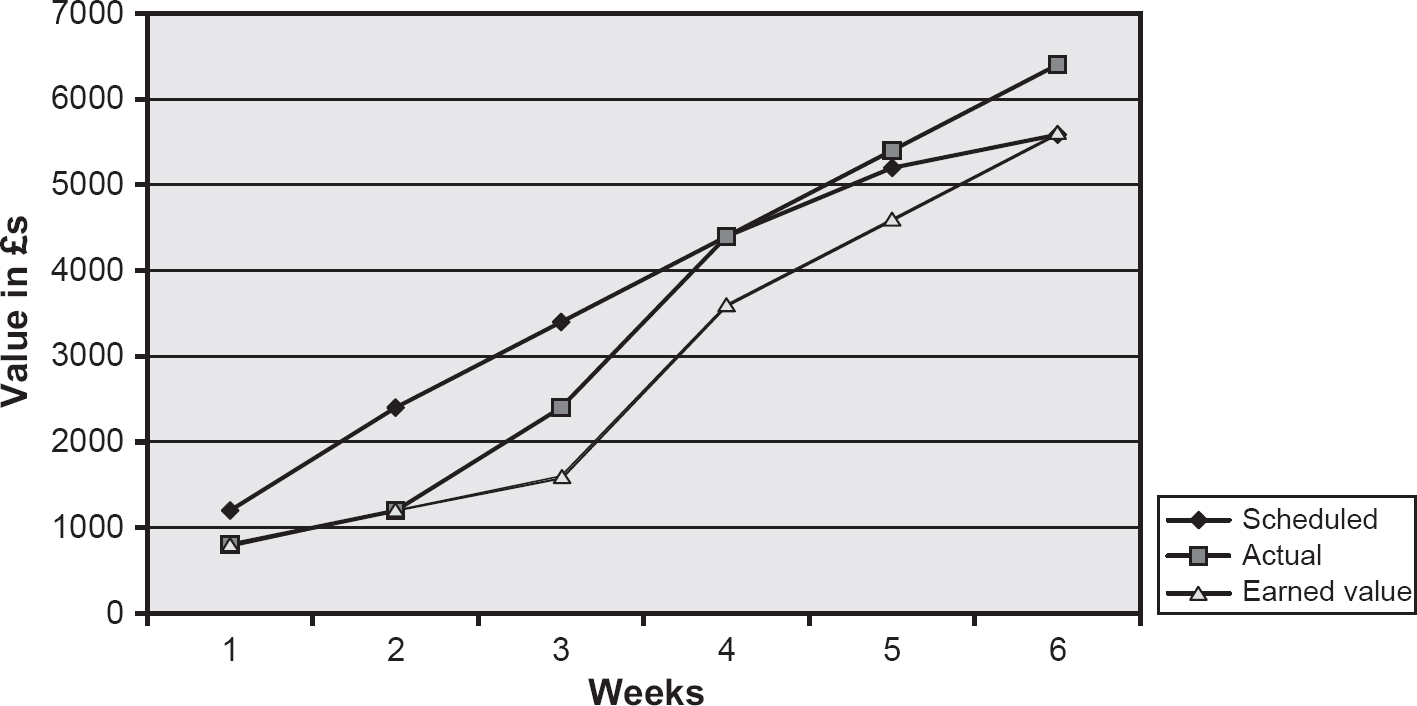

If we plot a third line, the earned value, then we can see if we are ahead or behind time, and above or below budget. Earned value analysis (EVA) shows the budget that was originally allocated to items of work that have been completed. When the work is finished, we can say that this value has been ‘earned’. If an external supplier is involved and had a contract with fixed prices to be paid on delivery of various products, they would see these payments as earned value.

As an example, activity G, ‘Write software’, is made up of a number of tasks that can be seen in Figure 2.11. To complete the overall activity within seven weeks, the supplier needs to have completed all the design work by the end of the second week of activity and all coding by the end of the sixth week. If the designers are priced at £400 a week, then at the end of the second week, four staff weeks of design work should have been completed. This means there is a planned value (PV) of £400 × 4 (that is, £1,600) at the end of the second week. Now if, for example, the task GA ‘Design provisional booking function’ is not completed, because that was originally planned as two weeks’ work, the earned value (EV) at this point in time would be only £400 × 2 for the work completed in tasks GC and GE (that is, £800).

Two ratios provide guidance on the progress of the project. The schedule performance indicator (SPI) is calculated by dividing the current EV by the corresponding PV. In the example above, this is £800/£1600, that is, 0.5. A ratio value below 1.00 means the project is behind schedule. The cost performance indicator (CPI) is the EV divided by the actual cost (AC) of the work completed. The £800 value earned by the completion of tasks GC and GE costs £800, so EV/AC is 1.00. This means that the costs are exactly those expected for the work done. An index value greater than 1.00 shows work costing less than expected, and a value less than 1.00 that there is a cost overrun.

In Figure 3.3, a line showing earned value has been added to the cumulative resource graph. This shows, for example, that at the end of week 6, the project is on schedule and has completed the work that was planned. However, it can be seen that expenditure is greater than planned. This may be a case where the project manager got the project back on schedule by buying in overtime.

Please note that candidates for the BCS Foundation Certificate in IS Project Management are not expected to know the details of how earned value is calculated.

1. Which of the following would you most expect to see in a routine report from a project manager to a project board?

a. Costs and benefits

b. Progress against plan

c. Configuration status information

d. Project staff appraisals

2. Which of the following is NOT involved in collecting progress information?

a. Team progress meetings

b. Timesheets

c. Comparing planned and actual costs

d. Informal monitoring

3. Which of the following would be most likely to give rise to an exception report?

a. A new issue being raised

b. A proposal to make a change to a deliverable

c. The unexpected loss of a key team member

d. Project tolerance being exceeded

4. What is the purpose of earned value analysis?

a. Assessing progress

b. Collecting progress information

c. Estimating the required effort

d. Calculating benefits

a. If we keep to the original planned installation rate of one marina/boatyard a day, 17 days (that is, about three to four weeks) are needed to complete installation, as there are 17 boatyards and marinas left. However, if we decide that the experience of the first week shows that the original installation rate was unrealistic, then we may project that three boatyards can be visited in a week. This would lead to between five and six weeks being needed to complete installation.

b. In the first scenario, the reason for only three boatyards being visited was simply a late start rather than a low installation rate. The remaining estimate of 17 days would seem to be reasonable.

In the second scenario, the reason for lateness was a lower installation rate. However, as the installation programme proceeds, the installation rate should improve as the nearer marinas and boatyards are dealt with, and journey times get shorter. Revising the planned time would be premature at this point.

This activity should illustrate how informal information gathering can help interpret more formal reports and the risk of extra learning time being needed if a new developer is added to the team who is unfamiliar with the application.

a. Option: be a week late and accept the penalty. The penalty would be £500, but there would also be the cost of an extra week’s work (£400). This would cost £400 + £500 in all – that is, £900.

b. Option: split the functionality into two components that can be developed in parallel. Currently £1,600 (4 × £400) has been allocated to the task. The new plan would increase this to £2,400 (6 × £400) – that is, an overall increase of £800.

c. Option: staggering delivery. There would be an extra week’s work for the delayed enhancement. This would cost £400.

Thus option (c) would appear to be the best. Note that this is a very simplified scenario, and does not take into account many issues such as the risk of possible loss of reputation with some of the options.

See Figure 3.4.

Figure 3.4 A Gantt chart that has been updated with actual progress up to week 4