When you have completed this chapter, you should be able to demonstrate an understanding of the following:

• relationship between programmes and projects;

• identification of stakeholders and their concerns;

• the project sponsor;

• establishment of the project authority (for example, project board, steering committee, etc.);

• membership of project board/steering committee;

• roles and responsibilities of the project manager, team managers and team leaders;

• desirable characteristics of a project manager;

• role of the project support office;

• the project team and matrix management;

• reporting structures and responsibilities;

• management styles and communication;

• team building and dynamics.

The aim of this book is to describe ‘best practice’ in project management. Unfortunately, not all organisations follow these good practices, which is one of the reasons why there are project failures.

Some of these good practices relate directly to the personal skills and qualities of the project manager, but others relate to the organisational structures within which the project manager and the project team works. In this chapter, we describe the elements of the project management structure and roles that should exist in an organisation planning and executing a project. These roles may be known by different names, so wherever possible we will give commonly used alternative names of which we are aware. We will also touch upon the management approaches that project managers might adopt and the strategies for effective communication within the project.

A programme is a collection or group of related projects. IT projects are often treated as individual and separate undertakings with their own distinct aims and objectives. However, sometimes grouping projects into programmes has advantages:

• Reduction of duplication – two projects may be developing a similar product.

• Coordination of resources – projects inevitably place demands on an organisation’s resources, and it is far better to coordinate than to compete for them.

• Management of interdependencies – if projects are dependent on one another, they have to be properly coordinated. In such circumstances, a change in one project may introduce a delay or a consequential change in another.

• Common objectives – sometimes several different projects need to be completed for a particular business objective to be achieved.

Typically, each project is assigned a project manager, while a programme is led by a programme director, who should be an influential member of the organisation’s senior management team acting as a champion for the programme. The senior status needed for this role means that it is usually only part-time. The role of programme manager is likely to be full-time and deals with the day-to-day coordination of the programme.

The integration of two businesses into one Water Holiday Company can illustrate the value of managing change as a programme of projects. The intention is to relocate the operations of the merged companies onto a ‘green-field’ site. In Chapter 7, we noted that the IT infrastructure installation would need to wait for the construction work to be completed. The construction work would use different sets of skills and resources to other integration activities, so could be usefully treated as a distinct project within a broader integration project.

The implementation team for the installation of the IT infrastructure would have their own concerns about having new premises suitable for the IT infrastructure. Thus coordination, particularly during the later stages of fitting out, would be needed that could be ensured through effective programme management.

A stakeholder is defined as anyone with a valid interest in an IT project or the products delivered by it. This group includes:

• all project personnel including managers, designers and developers;

• users, sponsors and other members of the organisation affected by the project;

• suppliers of software, hardware, consultancy and so on, to the project;

• contractors and subcontractors;

• members of the business community and, of course, financial backers.

Part of the project initiation process establishes who these people are and identifies their needs and concerns. Processes will have to be set up to ensure that their interests are represented and that they are consulted and kept informed. A simple table, identifying the major stakeholders, their interests, concerns and contributions, can be the basis of a communication plan – see Section 8.12 and Table 8.3.

ACTIVITY 8.1

List the main stakeholders in the Water Holiday Company integration project.

A formal management structure is needed with defined project roles:

• Named personnel should be allocated to the roles, but several people may share a role and a single person may have more than one role.

• Roles must carry appropriate authority, and responsibility. Accountability is sometimes distinguished from responsibility. Broadly, it refers to having a duty to ensure something is done to meet a project requirement. Those responsible for carrying out the practical tasks needed to fulfil the requirement are monitored by the accountable person.

• Individuals must carry out their roles correctly and willingly and must clearly understand the objectives behind their work.

• Status within the organisation is not sufficient qualification for a particular role. Previous experience and/or training in the role is needed.

At the top of the project organisation is a project sponsor. This person would be a senior person within the organisation where the new system will be implemented. They champion the project at an appropriately high and influential level – normally board level. They represent the ultimate authority for the project. Crucially, the sponsor controls the funds to pay for the project. Below the project sponsor are the following roles:

• project board (or steering committee or project management board);

• project manager;

• project team leader/manager;

• team member.

In parallel to this structure there could be other functions:

• project assurance team;

• project support office or project management office;

• configuration management team.

The roles that they represent should be present in all projects to a greater or lesser degree, although they may have different names. Where a project is small, for example, the project manager and project team leader roles could be carried out by a single person.

We noted earlier the role of the project sponsor who is guardian of the business case for the project. They represent the customer who supplies finance for the project to be completed in order to achieve the benefits that fulfil their needs.

The project board provides a forum in which critical issues can be discussed and decisions taken that are outside the remit and competence of the project manager. The same function may be served by a steering committee or a project management board. This group includes the project sponsor or their representative and representatives of other major stakeholders. The PRINCE2 standard explicitly identifies the need for a senior supplier and user to be present. The group is not democratic as the project sponsor (referred to sometimes as the ‘Executive’ or the ‘Senior Responsible Owner’) chairs the meeting and has the final say.

Members of the board must be able to agree decisions relevant for their areas of responsibility. If they cannot, they will have to refer decisions back to their managers, and thus delay the project. However, if they are at too high a level, they may attend meetings infrequently, leading to ineffective decision-making.

All projects should derive from the organisation’s business strategy and meet specific business and corporate objectives. It is therefore the role of the project sponsor, apart from looking after the money, to ensure that the project:

• stays in line with the corporate objectives;

• meets the business requirements;

• retains its business case (that is, that the benefits continue to outweigh the costs of the project).

The project board/project steering committee must have one or more representatives of the users. These should ensure that the user requirements are captured, and deliverables are signed off as acceptable. They must check that changes to requirements are in line with the business needs and do not jeopardise the overall project objectives. As was seen in Chapter 4, a volume of perfectly valid changes can delay the project to such an extent that it will not deliver the expected benefits.

Suppliers of technical resources, including skilled staff and the software and equipment to be supplied, should be represented. They should also support the development team and, when necessary, represent their interests as difficulties arise, for example in the face of continual change requests. Sometimes the project manager could carry out this role.

If all or part of the project is contracted to an external supplier, that organisation should be represented. If there are a number of contractors, then more than one supplier representative may be required. However, this could detract from the main purpose of the project board/steering committee and therefore it may be more effective to set up a separate group to manage the external suppliers.

The project assurance function could also have a representative on the board or could report via another member of the board, ideally the project sponsor.

Large, geographically dispersed projects may need several user representatives, but care must be taken that the board is not too big and thus ineffective. Subgroup meetings can give a voice to those who should have one without detracting from the efficient working of the board; smaller groups are usually more effective at decision-making.

The infrastructure management of the business, responsible for the platforms on which the delivered IT will run, may be represented. Development staff are more likely to be project-orientated with a single project as their priority, while the work of infrastructure support staff may be structured by job queues dealing with requests from many different users with different needs and priorities. These two valid outlooks need to be carefully reconciled.

The project board is a decision-making body. It holds the purse-strings through the project sponsor and therefore has ultimate control. The project manager will often be appointed by and report to the board. The board establishes the terms of reference and provides the management framework within which the project manager operates. It is the final arbiter on whether the project has met its objectives. In summary, the board initiates the project, controls its execution and eventually closes it down. Led by the project sponsor, it approves the following:

• project terms of reference (including the project initiation document);

• business case;

• budget;

• project plans;

• changes to project plans;

• quality plans, control and assurance processes;

• risk assessment and contingency plans;

• major changes to project requirements.

It receives feedback on the progress of the project from the project manager and also from the quality assurance function. The feedback enables them to sign off each stage of the project or other activity as defined in the plan, or require that it be reworked. It thus exercises overall control of the project.

In the following sections, references to the project sponsor usually mean the ‘project sponsor working through the project board/steering committee’.

The project manager is pivotal in the organisation of the project and has overall responsibility for the day-to-day management of the project. The role of the project manager is to ensure that the project is delivered on time, within budget and with the specified functions and quality.

The project manager produces, with the help of others, the various plans for the project (see Chapter 2). They monitor progress against the plan and make adjustments throughout the project. As milestones are reached, progress is reported to the board and team members (see Chapter 3). The project manager is set tolerances for activity completion and costs within which to work. Any deviation in the plans likely to take the project outside these tolerances should be reported to the board via an exception report with recommendations about the actions the project manager feels are necessary to correct the situation or to reduce its effect.

Inevitably, changes come along. The project manager assesses their impact on the project and reports to the board. It is the responsibility of the board to decide whether or not changes should be implemented, although, as seen in Chapter 4, this responsibility may be delegated, within constraints, to a change control board.

Should a risk materialise that is likely to affect agreed plans, the project manager will approach the board for permission to put into effect any agreed contingency plan. The project manager is accountable for keeping up-to-date logs of both change requests and risks (see Chapters 4 and 7, respectively).

Because project managers have to lead their projects, they must be able to set clear goals so that those who report to them are aware of what is required. The simple production of plans and schedules does not by itself achieve this – see Section 8.5.

The terms team leader and team manager are often used interchangeably. However, it is useful to distinguish between the two roles. Team leaders are each responsible for their own individual work team carrying out specific tasks needed to implement a work package. Team managers are in overall charge of a pool of specialist developers. They would have overall accountability for the execution of work packages authorised by the project manager.

Team leaders are close to the action. A team leader may be responsible for a specialist group of analysts, designers or programmers and hence work on a very specific part of the life cycle. Alternatively, on smaller projects, a team leader may lead a mixed team, in which case the responsibilities would encompass the whole of the life cycle. In the case of small projects, the project manager and team leader roles could be merged.

A team leader usually needs technical experience and knowledge. One specialised area is that of testing, where a team becomes expert at the creation of test data based on the requirements specification, which is then run through the software to see whether or not they meet those requirements.

Team leaders have the task of allocating the tasks needed to implement an authorised work package to specific individuals and helping them to complete the activities within the scheduled time scales. They also act as mentors or advisers when necessary. They must be aware of how well their part of the project is going. They should be able to quickly notify the project manager (perhaps through a team manager) of delays so that action can be started to bring the project back on course before it goes seriously adrift.

However good the structure may be, without competent team members the project will not succeed. Ideally, team leaders should be able to select their teams. This is rarely possible, so the team leader has to be familiar with the qualities of the staff allocated to them and assign them to the tasks which most match their capabilities.

As we will see in Section 8.8 on matrix management, specialist staff often have only a short-term project relationship with the team leader, while their longer term development and deployment is the responsibility of a separate technical head (who could be called a team manager).

This is usually a function rather than an actual team. The project sponsor and project board are accountable for project assurance; that is, they will be held to account for the good governance of the project. However, depending on the size and nature of the project, it is normal for responsibilities for project assurance to be delegated to one person or a small group. The tasks are the same; it is just the degree of activity that differs. Members of the project assurance function are appointed by and report directly to the project sponsor and the project board, not to the project manager. Their role is firstly project assurance (see Chapter 5), which focuses on ensuring that the project management procedures laid down in the project management plan are being followed effectively; for example, do the reports to the project board accurately reflect the true status of the project? Is risk management successfully controlling risks? Is the business case still relevant? They are responsible for checking that the quality control activities in the quality plan are carried out, standards are observed and procedures are followed. They will almost certainly not be carrying out quality control activities, such as testing, themselves. Being independent of the project manager, they can give an objective view on the quality of the products delivered and not just the timeliness of their arrival.

In the early stages of a project, the team would contribute to the setting of standards, the creation of procedures and the establishment of the quality review, quality assurance processes and the quality plan. This is particularly useful if the project is venturing into areas of technology that are new to the organisation.

A large, complex IT project may need several people for this activity, each with their own specialism, such as security. Three specific roles sometimes identified are:

• business assurance co-ordinator, who, for example, would make sure that the IT application under development is compatible with existing business procedures;

• technical assurance co-ordinator, who would ensure that the operational environment is not compromised by the new system;

• user assurance co-ordinator, who ensures the application meets user needs.

ACTIVITY 8.2

Identify two managers that you have reported to. It could be one was more effective than the other. What were their good qualities and defects as managers?

The role of the project manager is crucial. IT project managers traditionally progressed from technical areas such as software development through system design and team leadership to project management. However, this is changing as IT projects are perceived more and more as business change programmes. (Put another way, nearly every business change programme will have IT elements.) It is also the case that the project management role is increasingly involved in managing the external suppliers of services.

Thus, while it is useful to have familiarity with IT issues and concerns, it is not always essential in order to manage what may really be a business change project. It is more important to have other skills and characteristics. A key quality is good communication skills at all levels. The project manager often needs to present a convincing case for a course of action to higher management. Stakeholders have to be kept informed and the project teams must be motivated. To gain the respect and confidence of those around them, project managers have to be effective communicators, good managers and effective organisers.

They need to have skills in:

• leadership (which includes the ability to provide direction and guidance when needed);

• motivation;

• planning;

• negotiation (being firm, flexible and able to compromise where appropriate);

• delegation.

They need to be:

• responsible;

• reliable;

• available (not just for this project, but contactable at all reasonable times);

• intelligent;

• sociable (able to mix well);

• approachable (they should be good listeners);

• knowledgeable in the business area for the particular project.

These characteristics do not just arrive with seniority. A potential project manager must possess some of these attributes and will need development in deficient areas before becoming fully effective.

Although this list may seem daunting, the ability of people who seem quite ‘ordinary’ to become competent project managers through application, self-discipline and appropriate training is remarkable.

The qualities we have associated with project leadership seem heroic, but projects have many mundane clerical activities that have to be performed regularly, effectively and efficiently. The project manager is accountable for them, but, given the pressures on project managers, it is more effective to delegate these tasks. This gives rise to what has become known as the project support office (PSO).

The organisational structure described in Section 8.4 is usually set up for a specific project. This means that the project board and project manager are appointed for a single project. The PSO, on the other hand, may be a longer living entity that supports several, often interrelated, projects. Where projects are interrelated, they may be coordinated as programmes. In these cases, it is convenient to combine project support with programme support – hence, we have a programme and project support office (PPSO).

The largely clerical nature of many of these tasks means that they are often amenable to automation, and this may be reducing the importance of the PSO. Instead, the concept of the variously named project or programme management office (PMO) – or even programme and project management office (PPMO) – has been developed, which is more focused on the strategic aspects of projects, such as training and the identification of good project management practice. This could include portfolio management, which is concerned, among other things, with the prioritisation of project proposals.

The precise tasks this office undertakes will vary, but some typical PSO services are described below.

Time recording is essential for project control. In the past, clerical staff would collect and process the information required, but nowadays it is likely that project staff submit timesheet details online. Relieved of routine clerical work, project managers can focus on where effort expended varies from that expected and take necessary actions.

As details of progress are passed to the PSO, staff can use appropriate tools to update the plans and highlight problems to the team leader or project manager. In the event of changes to project team membership, the PSO can revise the plans so that the project manager is aware of the impact of such changes and can make any necessary modifications or alert the board to potential problems.

The PSO can maintain project logs. The project manager can be warned of approaching risks via the risk register (see Chapter 7). Risks that have passed can also be noted. Requests for change (RFC) are recorded as they arrive and then passed on for action (see Chapter 4). Once again, there are tools that facilitate online input and the automated processing of data.

A great deal of time, most of which involves finding dates and times at which all parties are available, can be spent on arranging meetings. Aids such as electronic diaries make this easier, but it can still be time-consuming. Delegation to the PSO is natural. Having agreed dates and times, the PSO can:

• organise the necessary room and other requirements such as catering;

• issue the agenda – most meetings have a set agenda and it is simple to check with the chair of the meeting to see if any changes are required;

• circulate other documents needed – the PSO may already carry out the configuration control function, which controls the versions of documents;

• record and distribute the minutes of meetings – the key thing is to ensure that all actions are identified, along with who is responsible for carrying them out and in what time frame.

The whole of Chapter 4 has been given over to change control and configuration management. The ability to keep track of documents and products to ensure that everybody is working with the latest version is very important to the success of the project. Like the PSO, within which it may function, configuration management has a life beyond the duration of the project, as the delivered IT system will continue to require amending and updating until it is finally replaced.

A project team is a small group of individuals with complementary capabilities working towards a common goal; they are responsible to and are guided and coordinated by a leader who is accountable to a project manager. We noted earlier that it was possible for the team leader and project manager roles to be merged.

A project team works in a different way from operational staff. It is brought together for the sole purpose of achieving the project objectives. On completion of the project, the project team can be disbanded. Team members are often drawn from specialist divisions within the organisation, such as the IT department, to work on the project and are assigned to other projects when it is over. Others may be selected from the user community as ‘super-users’ for their knowledge of the operational aspects of the application area and then return to their original jobs. The effect of being in a project team will be quite different for the two types of people, as will their expectations during and after the project.

Project team members are not always located together, although this is best; the team could be geographically dispersed. It may be possible to bring them together for short periods, but this would be expensive. Part of the solution to these problems could be matrix management.

So far it has been assumed that all staff report to the project manager, either directly or through team managers or leaders. This is the best way of managing a project but is not always practical, particularly if team members are drawn from a variety of departments.

Senior staff on a project – for example, team leaders – normally report to the project manager. On large projects there could be a hierarchy where more junior team leaders report to the project manager through more senior, higher-level leaders. Management control may be weakened if there is not a clearly defined reporting structure, to the detriment of the project.

In matrix-managed teams, an individual reports to more than one person. One example of matrix management can be found on board a naval ship. The captain of the ship is responsible for everything that happens on the ship when it is at sea. Its complement of sailors will include navigators, engineers, electricians, cooks, medical staff and others. Each specialised trade will also have a shore-based manager to whom they will report and who is responsible for their performance on the ship and their training when ashore.

In an IT environment, many part-time team members are juggling their time between projects and have a line manager outside the project. The project manager would want commitments from line managers that required staff will be made available when needed for a project.

Organisations generally have a number of projects under way at the same time, each requiring a range of different skills. For example, business analysts may elicit requirements from the users and ensure that they are clearly understood by the technical members of the project team. Analysts and designers would then need to convert the requirements into a design specification. They could come from a specialist department and normally report to a separate manager. Another department manages the IT infrastructure. They could second someone to the project to guide the designers so that the proposed solutions are compatible with the existing infrastructure.

Both software developers and testers could come from separate pools of specialists, or even come from a specialist group outside the organisation.

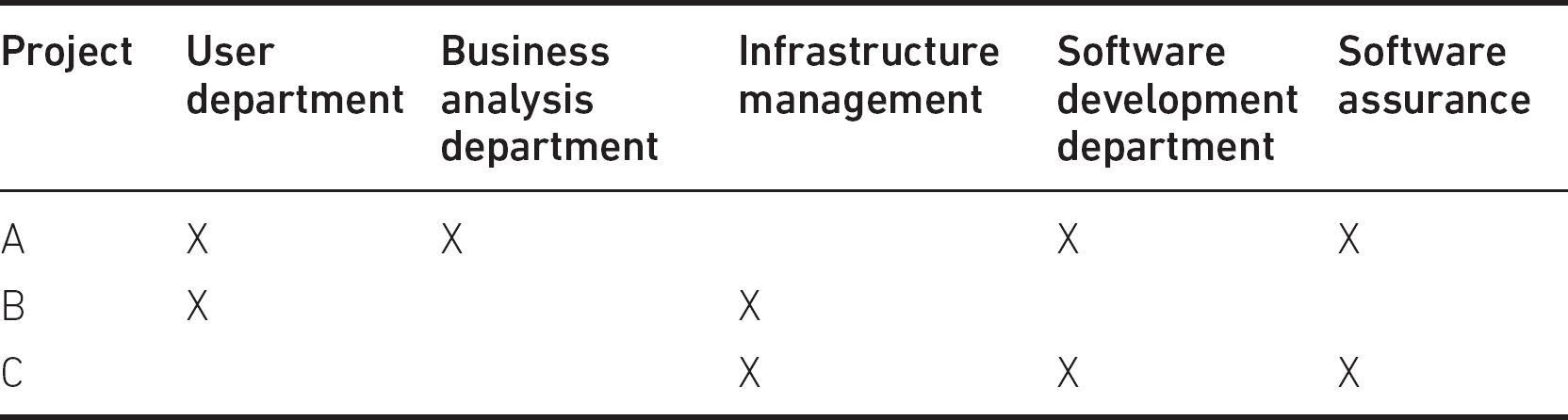

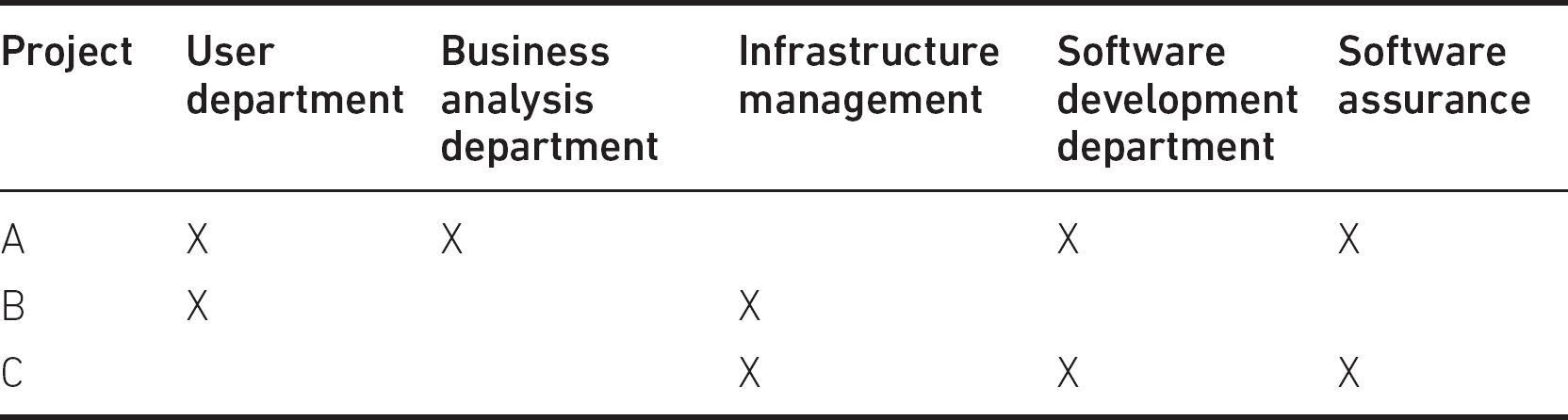

Putting all these together gives rise to a matrix structure as shown in Table 8.1.

Table 8.1 Example of a matrix organisation

This sort of structure has the advantage that the project manager has a team of specialists and can concentrate on the project in hand and not be concerned with issues such as the long-term development of the staff involved. A risk is that a line manager could call their staff off the project for some higher priority task, such as emergency maintenance on an operational system. These issues should be discussed at the beginning of the project and a strategy agreed by the project board, to which all line managers sign up.

Even where all staff, including the project managers, work for the same line manager, they could be allocated to more than one project. Each person may have their own perceived priorities and may put more effort into one project than another. This can lead to slippage on some projects, while others progress to schedule.

We noted in Section 8.2 that where many projects are carried out at the same time, particularly if they are related, there is often an umbrella organisation known as programme management. Where resources are limited, which is the normal situation, a programme director advised by a programme board would have the remit to make the final decisions about the allocation of resources between projects. While this may be irksome for the individual project manager, the organisation benefits as a whole. Obviously, plans have to be revised to take account of this situation and project managers cannot be held accountable for delays to their projects due to such changes.

With matrix management, the level of control that the project manager will have over the project team will vary. Where an individual is seconded to the project for its duration, then the project manager has greater control – as with the ship’s crew. This is in many ways the ideal, but it does have its drawbacks. With every project, the level of resource required will vary over time. For example, in the early, analysis stages of a project, several analysts but only one part-time designer may be required. However, as the analysis phase is completed, more designers may be required, but fewer analysts. If these staff were permanently with the project they would be underutilised at times, adding unnecessary costs to the project.

It is possible that a group of developers who already work together are employed on a project. However, as projects are by definition temporary organisations created to carry out one-off undertakings, it is often the case that a project will bring together people who have not all worked together previously.

A team in an IT project is usually a collection of specialists with a requirement to work together towards a common goal. The composition of the team is likely to be based on compromises and not be the ideal combination of skills and personal characteristics. There are many common-sense aspects and a number of theoretical approaches to developing an effective team.

The Tuckman–Jensen model describes four basic phases through which a team goes before it becomes fully effective:

• Forming: The group members have just been brought together and are probably hesitant about their new environment, unsure of their new colleagues and possibly nervous about future developments. Members are polite to one another, tend to accept authority and tread carefully. Some initial contact with colleagues reveals common ground and possible allegiances.

• Storming: Individuals within the group have started to assert themselves and to form alliances. Conflict may arise as ‘pecking orders’ become established. Aims and objectives are becoming clearer, but there are different views on how to proceed with the tasks ahead. Members now have a sense of belonging to a team, are gaining confidence and are likely to challenge the proposed methods of working.

• Norming: Internal conflicts are hopefully resolved, and the team members feel more comfortable and relaxed with their colleagues and their new surroundings. An acceptance of common values and behaviours develops, with open communication and constructive cooperation. The team starts to work as it should, with its overall capability being greater than the sum of its parts.

• Performing: The team is fully functional and has become a cohesive unit. Team morale is high, with good cooperation between members and a shared responsibility for the common goal. Team members are working hard and getting satisfaction as the team achieves its goals.

A fifth stage, adjourning, is sometimes added to describe when the team breaks up at the end of the project. The Tuckman–Jensen sequence of phases clearly represents the ideal team development. Good team leadership and people management are essential to allow the team to progress through the phases, and indeed the final stage may never be achieved if the personnel or the project circumstances are not right. It is quite possible to slip back a stage or two if unexpected developments are not well managed; for example:

• changes in team personnel – new arrivals can disrupt team morale and stability;

• a change in direction of the project, which means much team effort has been wasted;

• a change of leadership, which may mean the team needs to adapt to a new management style and could revert to the storming stage.

COMPLEMENTARY READING

The Thomas, Paul and Cadle (2012) book recommended as complementary reading at the end of this chapter gives more detail on the Tuckman and Jenson model with further references.

Building a team involves finding people with the appropriate skills who are available when you need them and are motivated to perform the tasks required of them. However, if the team is to work well together, a satisfactory mix of personality types and personal attributes is essential. A system for analysing and categorising people’s personal characteristics was developed by Meredith Belbin, who defined nine team roles:

• shaper – an energetic team member with a strong need for achievement who drives the team along;

• plant – a creative and innovative team member (the term ‘plant’ is used because it was found that planting such a person in an uninspiring team was a good way to improve its performance);

• resource investigator – a team member who makes contacts outside the group to bring in ideas and information and to acquire materials/resources;

• co-ordinator – a chairperson who promotes decision-making and delegates well (not necessarily the team leader);

• monitor evaluator – a team member who is analytical and able to assess ideas and options, but is not creative;

• team worker – a team member who helps to maintain team spirit and cohesion;

• completer finisher – a conscientious and painstaking team member who is concerned with getting things finished (this is a very important team trait);

• implementer – a team member who attends to details, is hard-working and organises the practical side of the project;

• technical specialist – someone who can provide the team with technical expertise.

COMPLEMENTARY READING

For further details, see Meredith Belbin, R. (2013) Management Teams: Why they succeed or fail, 3rd edn. Abingdon: Routledge.

It is not suggested that a team has to have one person of each type or that each team member falls into only one role. An individual can have attributes from a number of different roles. The idea is that a team needs a satisfactory mix of roles played by its members to perform well. A Meredith Belbin analysis may help to define a team weakness, or indeed to clarify the reasons why a team is not performing well or why conflicts keep arising in an otherwise skilled, competent team.

There are as many styles of management as there are managers. Much depends on the personality and capability of the manager (or leader) and the prevailing circumstances. The manager may have a natural preference for a certain style, but to be successful must vary their style to suit the circumstances.

For example, a task-orientated leadership style is sometimes distinguished from a relationship-orientated leadership style. Task orientation focuses on the technical aspects of the work, while relationship orientation emphasises such things as individual motivation and team morale. When a team is developing – the forming stage – it will need more direction than when it is fully functioning – the performing phase. A task-orientated approach would be more effective than a relationship-orientated approach because the team members are not yet familiar enough with the tasks to be carried out and the environment in which they are to be carried out.

Leadership often has two phases. The first is where events demand a response and the leader needs to decide upon an effective course of action. This is followed by the implementation of the chosen course of action. The general approaches to this have been analysed on two axes: autocratic versus democratic and directive versus permissive:

• directive autocrat: the leader makes decisions alone and closely supervises their implementation;

• permissive autocrat: the leader makes decisions alone, but subordinates have latitude in their implementation;

• directive democrat: the leader makes decisions participatively, but implementation is closely supervised;

• permissive democrat: the leader makes decisions participatively, and subordinates have latitude in their implementation.

Individual team members will react differently to these approaches. Some prefer to have clear direction and to leave decision-making to others, whereas other team members like to play a part in establishing the direction of the project.

Autocratic/directive management provides clear direction and quick decisions. The leader is seen to be decisive, firm and effective. It may well be that the leader genuinely has technical knowledge and expertise that exceeds that of their subordinates. However, it can be synonymous with an uncaring, remote, unapproachable, controlling or bullying management style, which can demotivate a team.

Democratic/permissive management shares responsibility for decision-making and for the team’s performance; thus, the team is likely to be more committed. However, this style can be perceived as weak and management can be seen as avoiding responsibility for difficult decisions. It may be difficult to enforce discipline if conflicts develop.

The ideal is a situational management style, which adapts to the demands of a situation. In some situations the task to be done is complex and needs to coordinate the efforts of different specialists. It could also be time-constrained – for example, when a critical operational system is being modified. In this case, the manager/leader would need to seek the advice of different specialists and consult on how they were going to work together. This would be ‘democratic’. The actual implementation would need tight discipline and would be ‘directive’.

In another example, there could be a central demand for compliance with a statutory requirement related, for example, to data security. The way the requirement is implemented might vary between the different systems in an organisation because of variations in their interfaces. Here, the autocratic demand for compliance could be tempered by a permissive approach about how the requirements are met.

Whichever approach is used, the project manager must be an accomplished communicator and have the ability to use the most appropriate methods of communication in order to be fully effective.

A project can be seen as a network of stakeholders or participants (including managers, users and developers) who each have particular needs to communicate with other stakeholders.

On the one hand, effective communication is needed so that, for example, co-workers are made aware of changes to project plans, requirements and designs that are the basis for their work. On the other hand, there is a risk of information overload when project participants are overwhelmed by information, much of which is not relevant.

Consideration must therefore be given to the information needs of project participants as well as the best methods to satisfy the needs. This leads to a communication plan.

ACTIVITY 8.3

It does not take long for the Water Holiday Company to realise that the integration of Canal Dreams and Minotours onto a single green-field site location and the transfer to a single booking system is going to take considerable time to implement. In the short term it is decided to keep the back-end booking functions of the two subsidiary companies separate and to retain the existing staff for at least two years. A single Water Holiday Company website is to be built with a common front end. The front end will conform visually to a style guide produced for the Water Holiday Company by a marketing consultancy. As far as booking is concerned, this should look as similar as possible for the two types of holiday, but may diverge to deal with differences with the products/services provided by Canal Dreams and Minotours. The new interface is to be designed and implemented by an external supplier, XYZ Systems. The work is to be treated as a project within the over-arching Water Holiday Company integration programme.

1. What information will XYZ need from the Water Holiday Company and its Canal Dreams and Minotours subsidiaries?

2. Where will the information come from and how will it be acquired?

3. What information would XYZ need to supply to the Water Holiday Company during the project?

Methods can be categorised as active or passive and as formal or informal. Active methods, such as a telephone conversation, require a response or reaction so that there is reinforcement or confirmation that the information or message has been received and understood. Passive methods such as a newsletter require no such confirmation. They leave to chance whether anyone reads or understands the material and should not be used for important messages.

Formal methods of communication have a set structure, such as a meeting of a project board, in contrast to informal methods such as a conversation, which carries no particular format and is not usually recorded.

It is also possible to categorise methods depending on whether the participants have to be available at the same time and/or in the same place for communication to take place (see Table 8.2).

By categorising methods in this way, it is possible to assess the suitability of possible methods of meeting a communication need. For example, you may decide that a short, weekly face-to-face meeting (an active, formal method that is same time/place) with the project sponsor would be better than an email (different time/place). This should be documented in the communication plan.

Table 8.2 Examples of same/different time/place communication

| Same place | Different place | |

| Same time | Face-to-face meetings | Telephone Video conferences Chat |

| Different time | Bulletin boards Pigeon-holes |

Documents Emails |

By setting out a detailed communications plan with all stakeholders, rather than leaving things to chance, you stand a much better chance of getting it right. Table 8.3 is an example of an entry for one of the types of communication selected for a project.

Table 8.3 Example of entry in a communication plan

| Name/description | Joint application development session |

| Target audience | User representatives and business analysts |

| Purpose | To elicit user requirements |

| Frequency/event | 23rd April |

| Method of communication | Away day |

| Responsibility | Ann Smith (Project Manager) |

ACTIVITY 8.4

A critical success factor of the Water Holiday Company’s integration is the customer experience at the boatyards and marinas where customers pick up and drop off hired boats. These establishments are also important to the booking system, as it needs accurate, up-to-date information on boat availability taking account of periods of non-availability for maintenance and other reasons. Historically, the boatyards in the UK have tended to be owned by Canal Dreams (the result of a policy of gradually extending its reach over the UK canal network through a programme of acquiring local boatyards); whereas the marinas in Greece, that service the needs of Minotours, tend to be locally owned.

Given the scenario described in Activity 8.3, outline the main communication events with boatyards that might be planned, giving the purpose and proposed methods of communication.

IT-based tools can support communication. Where work groups are small and collocated, simple, non-technological techniques such as moving around cards on a pin board can be an excellent way of showing the current state of the flow of work in the group. This approach can be digitised by using a tool such as Trello – just one example among many – which can extend its reach to workers at distant locations. In Chapter 3 the use of Gantt charts to monitor projects was discussed; while these can provide an accurate overall picture of the project as a whole, they are unwieldy as a way of reflecting the immediate status of work for individual developers.

This chapter has only been able to touch briefly upon some aspects of organisational behaviour as it relates to projects. A good book on the important issues of organisational behaviour that goes beyond the immediate demands of the BCS Foundation Certificate in Project Management for Information Systems is recommended in the complementary reading.

Thomas, P., Paul, D. and Cadle, J. (2012) The Human Touch: Personal skills for professional success. Swindon: BCS.

1. Which of the following is NOT a name given to the group that has responsibility for committing resources to the project and approving variations to the project’s objectives?

a. project board

b. project management board

c. project support office

d. steering committee

2. Which of the following terms is used to describe an organisational structure where staff are responsible to a project manager for the duration of a project, but also have a manager who is responsible for their long-term staff development and work programme?

a. the Tuckman–Jensen model

b. configuration management

c. matrix management

d. task orientation/relationship orientation

3. At which stage of team formation does a team become fully functional as a cohesive group?

a. performing

b. norming

c. storming

d. forming

4. Which of the following is an example of different time/different place communication?

a. a project board meeting

b. a progress report document

c. a telephone conversation discussing a problem a user has with an IT system

d. video conferencing with the supplier of a software application

Stakeholders affected by the Water Holiday Company integration project include the two sets of booking staff at Canal Dreams and Minotours, customer-facing staff at boatyards and marinas, the owners of the new business entity, existing customers, previous and current management including the managing director, marketing manager, central finance, human resources department (who will have to carry out the delicate tasks relating to staff redundancy and relocation), premises management, building construction and fitting out specialists, and suppliers of IT and software products and services.

Without doubt many other stakeholders can be found!

Your answer will of course depend on your own experience. My own experience of the feedback from IT students returning from a year’s IT work placement was that by far the most frequent management failing was lack of communication between managers and staff. Often this could be put down to the excessive workloads put on managers.

Communication tends to be important because IT projects require inputs from many different resources and this creates many opportunities for misunderstanding.

As far as good qualities were concerned, this was more nebulous, but often the rather vague quality of ‘friendliness’ was used.

This was very much a ‘worm’s eye’ view of project management.

1. To answer this question properly you would need to identify the system life cycle that XYZ is going to use and then look at the external inputs for each phase. Let’s assume a design/build/test cycle:

• Design: The inputs to this will include system requirements, which include both business requirements and technical requirements about the existing back-end systems components that the front end will interface with. It will also need to know whether the system they have designed will be acceptable to the clients.

• Build: This will use the designs produced above. The designs may be elaborated as they are built, and so further reassurance about their acceptability is needed.

• Test: If good interface design practice has been followed, then some informal testing with prospective users will have been done at the Build stage. This will be a formal acceptance test using, as far as possible, real transactions.

2. Information sources and gathering methods:

• Some requirements will have been defined in the supplier selection process as the basis for the contract for work.

• The style guide exists as a document.

• Representative users from Canal Dreams and Minotours could be interviewed to clarify lower-level requirements, particularly differences in the processes at the two subsidiaries.

• Requirements at operational level ought to be signed off at managerial level to ensure they are compatible with longer term Water Holiday Company aspirations.

• Details of the interface may exist in documentation, but there is a risk that this is not up-to-date. Access to actual code is desirable.

• As transactions are built, demonstrations to booking specialists can obtain information about their acceptability. Note that there is the need to ensure alignment between the requirements of Water Holiday Company operational staff and Water Holiday Company management.

• Integration testing will provide information about compatibility with existing back-ends.

3. Information needed by the Water Holiday Company:

The information needed by the Water Holiday Company will mainly be concerned with the completion date. If the agreement with XYZ is fixed price, then costs will not be an issue. However, the basis for payment could be ‘time and materials’, which means that XYZ staff working for the Water Holiday Company keep a record of hours worked and XYZ then submit an invoice for payment for those hours. In this case, the Water Holiday Company will want details functionality completed and the type of work the developers have been doing.

XYZ will be anxious to record any changes to previously agreed requirements in order to ensure the additional costs are recouped. They would also want issues where Water Holiday Company staff have delayed progress to be recorded and resolved.