“Among the blacks is misery enough, God knows, but no poetry … Religion, indeed, has produced a Phyllis Whately [sic]; but it could not produce a poet.”

—Thomas Jefferson, 1784

Boston, Massachusetts, 1773

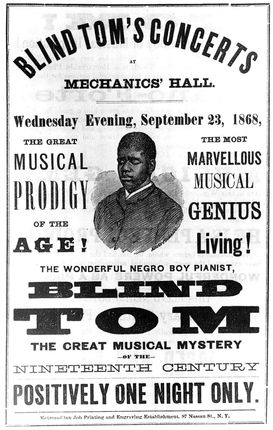

Only a very few slaves got a chance to develop their talents. Most who did were servants of liberal masters in the North, or slaves who had a special skill that whites found entertaining or worth money. A blind boy from Georgia known as Blind Tom showed such amazing talent as a composer and pianist that he was able to play his way to fame. Tom Molineaux, born a slave on a Virginia plantation, became a champion boxer. Onesimus, a slave owned by the Puritan minister Cotton Mather, helped find an inoculation against smallpox. Phillis Wheatley was a slim, shy, deeply religious girl. Born in Africa, she grew up in the home of wealthy Bostonians who taught her to read and encouraged her to write. In 1773, a collection of her poems, most written while she was in her teens, became the first book of poetry ever published by a black American. Many whites didn’t believe a slave girl could have written it. The poems spurred a hot debate about whether Negroes were actually capable of writing poetry at all.

A FAST LEARNER

“Without any assistance from the school of education, and by only what she was taught in her family, she, in sixteen months time from her arrival, attained the English language, to which she was an utter stranger before, to such a degree as to read any of the most difficult parts of the Sacred writings, to the astonishment of all who heard her.”

—John Wheatley

Phillis Wheatley’s real name is lost to history. She was born in 1753, probably near the Gambia River in the Senegal-Gambia region of Africa. Later she said that on the day she was captured, her “mother poured out water before the sun at his rising.” This may have meant that her people were Muslims, who pray when the sun rises. She was seven years old on the day she was taken from her family and village. Ships’ records show that her front baby teeth were missing.

After a march to the sea, the girl was probably chained and packed tightly into the hold of the schooner Phillis for a voyage to America. It is known that survivors reached Boston on July 11, 1761. Dressed only in a scrap of a rug, she climbed onto an auction block to be examined by buyers. She was bought by Susannah Wheatley, the wife of a rich Boston merchant, who wanted a girl to work in her house. When Mrs. Wheatley asked her name, the slave dealer answered with the name of his boat. The Wheatleys took Phillis to live in the servants’ quarters of their elegant home on King Street in Boston.

One day, not long after, Susannah and her eighteen-year-old daughter Mary came upon Phillis, her face screwed up in fierce concentration, marking the kitchen wall with a piece of chalk. They watched her silently for a while and finally realized she was trying to draw letters. Instead of punishing her, Mary Wheatley showed Phillis how to make them the right way and then began to teach her English. Phillis picked up the language with astonishing speed. A year later she could read the hardest passages in the Bible. By the time she was ten, Phillis was well on her way to mastering Latin and English literature.

Should you, my lord, while you peruse my song,

Wonder from whence my love of freedom sprung,

Whence flow these wishes from the common good,

By feeling hearts alone best understood,—

I, young in life, by seeming cruel fate

Was snatched from Afric’s fancied happy seat:

What pangs, excruciating must molest,

What sorrows labor in my parent’s breast!

Steeled was that soul, and by no misery moved,

That from a father seized his babe beloved:

Such, such my case. And can I then but pray

Others may never feel tyrannic sway?

Wonder from whence my love of freedom sprung,

Whence flow these wishes from the common good,

By feeling hearts alone best understood,—

I, young in life, by seeming cruel fate

Was snatched from Afric’s fancied happy seat:

What pangs, excruciating must molest,

What sorrows labor in my parent’s breast!

Steeled was that soul, and by no misery moved,

That from a father seized his babe beloved:

Such, such my case. And can I then but pray

Others may never feel tyrannic sway?

—Phillis Wheatley, 1772, from an untitled poem addressed to Britain’s William Legge, Earl of Dartmouth

With her own room, light duties, and the encouragement of her owners, Phillis Wheatley had a better chance to learn than many white colonial girls. But she still was not free, and her poems reflect her situation.

Like Phillis Wheatley, a sightless Georgia slave boy named Thomas Greene Bethune was given a chance to show his talent. An amazing pianist and on-the-spot composer, Thomas played his way to fame—and the fortune of a promoter who advertised him as “Blind Tom.”

The more Phillis learned, the more books and lessons the Wheatleys gave her. They let her read books by the great English poets of the time. Her favorite was Alexander Pope. The Wheatleys excused her from some chores to study and write. They even gave her a room of her own with a fireplace and a kerosene lamp by her pillow. She kept a pen and ink pot near her bed so she could write at night. Though she was a slave, Phillis was actually receiving a better chance to learn than most free children in Boston.

One night when Phillis was twelve, the Wheatleys invited a large group of friends over for dinner. As she served the guests, Phillis overheard two men recounting their adventure about having nearly drowned in a storm at sea off Cape Cod. After she cleared the table, Phillis rushed to her room, took her pen, and began to write the story in poetic verse. When she was finished, she showed it to Susannah Wheatley, who was so impressed that she got it published in a magazine.

After that, the Wheatleys began to take Phillis around to their friends to show her off. She lived in two worlds, not fully a part of either. She slept in a room of her own apart from the other slaves, so she had few black friends. Her life wasn’t hard, but she was still a slave; she wasn’t free. She recited poetry at the fine homes of wealthy white Bostonians, yet she wasn’t comfortable enough to eat at the main table with her hosts. She was baptized in the Wheatleys’ Congregational church, but she sat back in the gallery with other slaves during services. Her name was the same as the Wheatleys’, but her own family was in Africa, if they were still alive. There were mixed signals everywhere.

Phillis kept writing throughout her teens until she had composed thirty-nine poems—enough to make a book. Written in the style of great English poets, her poems were about freedom, faith, God, the growing tension between the colonists and Britain, and, sometimes, the death of children.

The Wheatleys took Phillis’s poems to publishers they knew, but no one would publish them because they didn’t believe that Phillis could have written them. In 1773, the Wheatleys persuaded eighteen leading Bostonians—including John Hancock, who later

signed the Declaration of Independence and would become the governor of Massachusetts—to write a letter to “the world” stating that they believed Phillis had written the poems. That was enough. Later that year her book, Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral, was published. The book sold well on both sides of the Atlantic.

But her poems made Phillis controversial. Thomas Jefferson refused to meet Phillis and called her poems “below the dignity of criticism.” On the other hand, George Washington visited with her for a half hour in 1776 and praised a poem Phillis had written about him. The problem was that poetry was considered the highest expression of the human imagination. Only superior people were supposed to be able to write poems good enough to be published. But Phillis was black, young, and African-born. She wrote most of her published poems as a teenager, a few when she was only twelve. Her elegant verses especially threatened slave-owning whites like Jefferson, who justified slavery by convincing themselves that blacks were inferior, maybe not even totally human. Jefferson argued that blacks couldn’t experience love in ways that inspired the imagination, and therefore couldn’t write poetry. But then here was this book—how could one explain Phillis Wheatley?

Phillis sailed with the Wheatleys to England, where publishers and critics praised her poems and pressured the Wheatleys to free Phillis. But soon the American Revolution against British rule destroyed the market for her poetry, especially in England. This cut off her income. Finally, in 1778, both Wheatleys died and Phillis was freed.

To those who opposed slavery, Phillis Wheatley’s poems proved that enormous talent, thought, and imagination were wasted by keeping Negroes from reading and writing. Though it was dangerous for Phillis to criticize slavery directly, she revealed her inner feelings in a few poems, such as the untitled poem on here, in which she imagines the pain her father must have felt when she was taken from him.

She married a man named John Peters. They had three children, who all died as babies. After her unhappy marriage ended, Phillis spent her final days in poverty, living in a boardinghouse and working as a maid. She died alone at the age of thirty-one. Even a hundred years after her death, Phillis Wheatley was still known as the “mother of black literature in America.” She was an important model for white female poets, too, since she used her own name when many other women writers of her time used men’s names in order to be published.

A LETTER TO DOUBTERS

“We whose Names are underwritten do assure the World that the Poems specified in the following Page were (as we verily believe) written by PHILLIS, a young Negro Girl, who was but a few Years since, brought an uncultivated Barbarian from Africa, and has ever since been, and now is, under the Disadvantage of serving as a Slave in a family in this Town. She has been examined by some of the best judges, and is thought qualified to write them.”

—Eighteen prominent Bostonians, including the governor and lieutenant governor

USING PHILLIS WHEATLEY TO SCOLD THE COLONIES

“We are much concerned to find that this ingenious young woman as yet a slave. The people of Boston boast themselves chiefly on their principles of liberty. One such act as the purchase of her freedom, would, in our opinion, have done them more honor than hanging a thousand trees with ribbons and emblems.”

—The Monthly Review of London, December 1773

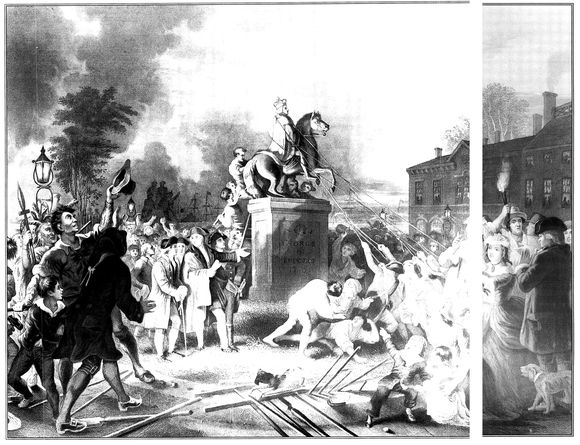

Patriots pulling down a statue of King George III in New York City

We have an old mother that peevish is grown

She snubs us like children that scarce walk alone

She forgets we’re grown up and have sense of our own

Which nobody can deny, deny

Which nobody can deny.

If we don’t obey orders, whatever the case

She frowns, and she chides and she loses all patience

And sometimes she hits us a slap in the face

Which nobody can deny, deny

Which nobody can deny.

She snubs us like children that scarce walk alone

She forgets we’re grown up and have sense of our own

Which nobody can deny, deny

Which nobody can deny.

If we don’t obey orders, whatever the case

She frowns, and she chides and she loses all patience

And sometimes she hits us a slap in the face

Which nobody can deny, deny

Which nobody can deny.

—Benjamin Franklin