![]()

Irreconcilable DifferencesIrreconcilable Differences

THE WAR OF 1812 was the result of a complicated mixture of politics, expansionism, economics, and idealism. At its root, the United States declared war on England because of constant violations of American rights at sea and English efforts to thwart American expansion to the Mississippi River. For the people living along the Chesapeake Bay in Maryland and Virginia, freedom of the seas resonated much more than did outcries over British actions in the west. From Baltimore to Norfolk, the sea was the lifeblood of the economy, and many families protested the loss of loved ones to British impressment.

As early as 1792, just nine years after the end of the Revolutionary War, American diplomats protested to their English counterparts about British impressment gangs seizing American seamen while they were in English ports.1 British warships were also stopping American merchantmen on the high seas and forcibly removing alleged Royal Navy deserters.2 Even U.S. warships were not immune to British impressment. U.S. Navy commanders complained bitterly about British efforts to entice American crewmen to desert when Yankee frigates arrived in British ports such as Gibraltar and Malta, and there were reports of British press gangs waiting by the docks to snatch American bluejackets.3

England earned even more enmity from America in 1807 when it adopted a European-wide blockade. Napoleon, who controlled most of the continent, had declared he would seize as a blockade-runner any vessel trading in English ports or with English allies or colonies. England, in a tit-for-tat economic move, adopted Orders in Council essentially declaring all of continental Europe off-limits to neutral shipping. The British began seizing American merchant vessels that ventured into European waters, selling the boats and cargo to help pay for the war and impressing the seamen into the Royal Navy.4

The United States viewed the Orders in Council as a direct attack on its economy, although enough American merchants did business with England to offset some of the losses. The British economic sanctions hit the merchants and shipowners of Baltimore particularly hard.

Hundreds of schooners, brigs, and ships sailed from Baltimore for the West Indies, South America, and the Mediterranean, and they often had to sneak past British ships blockading ports under French control. Italian ports were especially confusing as they changed hands between Austria (a British ally), Spain (first a French ally, then a British ally), France, and England. The American merchants who stocked the ships with raw materials and other goods coveted in Europe did not care who controlled the ports as long as their ship masters could land those goods, sell them, and then buy clothing, porcelain, spices, and other items in demand back home, which guaranteed a profit. Britain’s policies slowly put a stranglehold on business, however, and cost merchants and shipowners thousands of dollars in lost revenue. Many Americans blamed both the British and the French for their economic problems, with much of the blame falling on the British.5

President Thomas Jefferson answered the French and British actions with the Embargo Act of 1807, which outlawed foreign trade and further stifled the American economy. Exports plummeted from $108 million in 1807 to just $22 million in 1808. Imports plunged from $138 million to just $57 million over the same span. The only saving grace for the economy came from the coastal trade and the often-winked-at smuggling trade that quickly cropped up. American merchant vessels would find themselves “blown off course” and, in desperation, would seek shelter in a Caribbean port, where the locals just happened to want to buy the ship’s cargo.6 The Embargo Act lasted just two years, but its repeal did not provide the economic bounce-back newly elected president James Madison and his backers expected. Trade with England did rebound to nearly pre-1807 levels, but trade with France remained stagnant.7

Impressment, however, caused far more anger among Americans than did economic policies. Part of the dispute stemmed from how the United States and Great Britain viewed citizenship. American shipowners believed anyone who enrolled in the crew, no matter where he was born, could become an American by taking an oath of citizenship. Britain refused to recognize the legitimacy of a British citizen’s oath to another country and claimed the right to seize any British man serving on board vessels flying a flag other than the Union Jack. The British also claimed the right to remove Danes, Swedes, Portuguese, Spanish, or French sailors from neutral vessels on the grounds that they, at varying times, were enemies of the Crown and therefore legitimate prisoners of war.8

It was a policy that would not change as long as Great Britain remained locked in its life-or-death struggle with France, and it was this attitude that rankled Americans. Secretary of State Timothy Pickering, in a 1796 letter to the U.S. minister to London, Rufus King, expressed the frustration many Americans felt when he claimed:

The injustice of the British claim and the cruelty of the British practice, have tested, for a series of years, the pride and patience of the American government. . . . The claim of Great Britain, in its theory, was limited to the right of seeking and impressing its own subjects, on board of the merchant vessels of the United States, although, in fatal experience, it has been extended (as already appears) to the seizure of the subjects of every other power, sailing under a voluntary contract with the American merchant; to the seizure of the naturalized citizens of the United States, sailing, also, under voluntary contracts, which every foreigner, independent of any act of naturalization, is at liberty to form in every country; and even to the seizure of the native citizens of the United States, sailing on board the ships of their own nation, in the prosecution of a lawful commerce.9

A decade later the situation had only grown worse. War nearly broke out in 1807 after the frigate HMS Leopard attacked the U.S. frigate Chesapeake on the grounds that the American warship had numerous British deserters among her crew. After winning the presidency in 1808, Madison began making a case for war with England. In addition to what he called British transgressions at sea, Madison pointed out that Great Britain had yet to abide by the Treaty of Paris of 1783, which granted America its independence. Britain was supposed to abandon its forts along the Ohio River and in the Northwest Territory—Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, and Michigan—but instead kept many of its garrisons in place to forestall the westward growth of the United States. England also armed the Native Americans who resisted the American settlers as they pushed into new territories.10

The anger built in states such as Maryland, where commerce was the lifeblood of the local economy, and by 1811 had finally reached a boiling point. The Maryland state legislature, on November 26, 1811, issued a resolution condemning Great Britain and lauding President Madison, and sent it to the U.S. Congress:

Whereas, It is highly important at this eventful crisis in our foreign relations, that the opinions and feelings of every section of the union should be fairly and fully expressed; Therefore, we the legislature of Maryland do Resolve, That in the opinion of this legislature, the measures of the administration with respect to Great Britain have been honorable, impartial and just; that in their negotiations they have evinced every disposition to terminate our differences on terms not incompatible with our national honor, and that they deserve the confidence and support of the nation;

Resolved, That the measures of Great Britain have been, and still are destructive of our best and dearest rights, and being inconsistent with justice, with reason and with law, can be supported only by force; therefore if persisted in, by force should be resisted.11

Just six months later, fifty of the most prominent prowar businessmen in the state gathered at the Fountain Inn in Baltimore to adopt a resolution calling for war with England that was sent to the president: “The time has at length arrived when we must determine whether by tameness and submission we shall sink ourselves below the rank of an independent nation,” said businessman Joseph H. Nicholson, “or whether by a glorious or manly effort we shall permanently secure that independence which our forefathers handed down to us as the price of their blood and their treasure.”12 They got their wish on June 18, 1812, when James Madison became the first American president to ask Congress for—and to receive—a formal declaration of war on a foreign nation. The declaration divided the nation into pro- and antiwar camps.

Maryland, like much of the country, had a sizable antiwar population, but the most strident opposition came from New England, where ship and business owners feared a war with Britain would wreck the still-recovering economy. The Non-Intercourse Act of 1809, which had replaced the Embargo Act, allowed American merchants to conduct trade with any country except England or France but only slightly eased the pressure on the U.S. economy. Merchants, especially in New England, lobbied for complete freedom to resume their profitable trade with England.

The port town of Salem, Massachusetts, was one of the centers of New England antiwar sentiment. For the merchants of Salem, trade with England meant money not only for themselves but also for the country. Salem alone contributed more than $7 million of the $25 million in import duties the federal government collected in Massachusetts from 1801 to 1810.13 One ship from Salem, the 233-ton brig Leander, landed cargo from China that paid more than $179,000 in duties.14 Wealthy merchants in Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Charleston opposed the coming conflict for the same reasons as their New England counterparts.

The antiwar opposition was also highly politicized. Two parties dominated early American politics: the Democratic-Republicans, the party of Thomas Jefferson and Madison, and the Federalists. Aside from fundamental differences over what role the government should play in Americans’ daily lives, the two parties differed greatly on economic and diplomatic matters.

Federalist newspapers and members of Congress quickly presented a solid antiwar front. The tenor of the Federalists’ opposition was so strident that Democratic politicians threatened to treat opponents of the war as traitors. Robert Wright, for example, governor of Maryland from 1806 to 1808 and a U.S. representative in 1812, said in a speech prior to the declaration of war that if “the signs of treason and civil war discover themselves in any quarter of the American Empire the evil [will] soon be radically cured, by hemp and confiscation.”15

In Maryland, Federalist sentiment ran high among the residents of the Eastern Shore—the mostly agrarian part of the state between the Chesapeake Bay and Delaware—as well as in the state capital, Annapolis, and the farm country along the Patuxent and Potomac Rivers. There was also a small but extremely vocal Federalist minority in the radically Democratic city of Baltimore. The third largest city in the United States, after New York and Philadelphia, Baltimore had a large and unruly anti-British working class. City officials actually condoned periodic riots against the British and Federalists. Wright, as governor, once pardoned several people convicted of tarring and feathering a British shoemaker.16

The situation in Baltimore, with pro- and antiwar supporters clashing in the newspapers and sometimes on the streets, was something of a microcosm of the nation as a whole. The prowar supporters, in many cases, had very personal reasons for wanting war, whether it was trade, new land, or “sailors’ rights.” The antiwar supporters, who also loathed the practice of impressment, viewed war on a more national scale.17 If two men embodied these divisive forces in Maryland, they were Capt. Charles Gordon of the U.S. Navy and newspaper editor and lawyer Alexander C. Hanson.

![]()

There were likely few people in Baltimore as happy about the onset of the war as Gordon, who had a very personal grudge against England. Although he was a capable and well-respected naval officer, Gordon had not had an easy life, and he blamed his misfortunes on the British. Born in Chestertown, Maryland, in 1778, Gordon was one of the six children of Charles Gordon Sr., an English-born lawyer who immigrated to America in 1750. The elder Gordon married into the powerful Nicholson family of Maryland, but not even the Nicholsons could help their son-in-law when he expressed his unabashed support for England at the start of the Revolution. His Loyalist views were greatly at odds with those of the patriots of the Eastern Shore, and in 1780 the governor of Maryland ordered his arrest. The Nicholsons, staunch patriots, intervened, and the governor ordered Gordon’s exile. He left America, never to return.18

Gordon was two when his father left. Within two years of his father’s exile the Gordons had gone from being relatively wealthy to destitute. The state confiscated the family’s home and assets, forcing his mother to appeal to relatives for help. Gordon went to live with the Samuel Chew family in Chestertown. As he grew up, he had numerous fights with boys—his age and older—who accused him of being a Loyalist like his father. When his mother died in 1786, Gordon became a ward of the state.19 How he lived for the next thirteen years is a mystery, although he apparently received a better-than-average education, probably thanks to his powerful family connections. By the mid-1790s Gordon was a crewman on a merchant ship out of Baltimore, an experience that instilled in him a love of the sea. In 1794 a war scare with Algiers, one of the infamous Barbary States, goaded Congress into authorizing the creation of the U.S. Navy. Although another three years would pass before a single ship slid down the ways, Gordon applied for a warrant in the new force.

His connections to the Nicholson family helped Gordon secure an appointment as a midshipman in 1799, just in time to serve in the Quasi-War against France. He served first on the Insurgente, a captured French frigate, and then transferred to the frigate Constellation. Although he saw little combat action, Gordon impressed his superiors with his skill as a navigator and his seamanship. He earned a promotion to lieutenant within a year. Despite his lack of combat experience, Gordon was among the thirty-six lieutenants retained under the Peace Establishment Act that greatly reduced the size of the Navy at the end of the conflict with France.20

Gordon held a variety of posts over the next two years, serving on the frigates New York and Chesapeake in the first two years of the conflict with Tripoli that broke out in 1801. In 1803 he became the first lieutenant on the U.S. frigate Constitution and served in the squadron Edward Preble commanded. Gordon shined under Preble, earning the commodore’s commendation for his handling of the flagship and for bravery when Preble put him in command of a gunboat.

The campaign against Tripoli was the crucible that molded many young officers in the new navy. Gordon fought alongside Stephen Decatur, Charles Stewart, Isaac Hull, James Lawrence, Oliver Hazard Perry, Thomas Macdonough, and Richard Somers, and earned the respect of his peers. For perhaps the first time in his life, Gordon felt among equals. Like many of his brother officers he was from the Mid-Atlantic region, and he learned that no one cared about his father’s politics. All that mattered were his actions. He quickly won promotion to lieutenant commandant and then to master commandant.

In 1807 Gordon took command of the Chesapeake, then fitting out at Hampton Roads, Virginia, for a cruise to the Mediterranean.21 Although he commanded the frigate, Gordon found himself relegated to little more than a figurehead when Commodore James Barron claimed the Chesapeake as his flagship. Barron, not Gordon, would command the ship if she saw combat.

The Chesapeake was ill prepared for the cruise. Gordon took command of the frigate in April, and by June he was still working frantically to ready her for sea. The Chesapeake had been in ordinary—in mothballs—since 1805, and whole parts of the ship required reconstruction. Although the work was incomplete when Barron arrived in Norfolk in June, Gordon told the commodore the Chesapeake was ready for action. Barron, after a cursory inspection, agreed.22

Gordon also had the responsibility of recruiting the Chesapeake’s crew. Many Americans eagerly joined when offered an advance of a month’s pay but then promptly disappeared. Gordon believed he had no choice but to enlist men he knew were British. He likely tried to hide his misgivings about the crew as the Chesapeake pulled away from the dock on June 22, knowing the 50-gun Leopard was lurking off the coast. That ship’s commander, Capt. Salisbury Pryce Humphreys, had declared publicly he believed the Chesapeake had British subjects—including Royal Navy deserters—among her crew and had vowed to stop the American warship to retrieve them.

The two ships “met”—Humphreys was on the hunt for the Yankee frigate—off the Virginia coast. Humphreys ordered the Chesapeake to stop to allow a British boarding party to search her for British subjects. Barron, who outranked Gordon and held command of the Chesapeake, refused. The Leopard then fired four broadsides into the Chesapeake, killing three men and wounding eighteen (one died later from his wounds), and completely unnerving Barron. The commodore ordered the Chesapeake’s flag hauled down and offered to surrender. Humphreys refused. A British party boarded the Chesapeake and removed four crewmen—three of whom were in fact Americans.23

The incident touched off a firestorm of indignation in the United States. Citizens marched in the streets calling for war with England. The American people also demanded to know how one of their frigates could be so ill prepared for combat. Secretary of the Navy Robert Smith was just as incensed and ordered the court-martial of Gordon, Barron, and two other Chesapeake officers. Gordon faced charges of neglect of duty for not properly training (or “exercising”) his crew and for reporting the Chesapeake ready for sea when she was unfit for battle.24

In his defense, Gordon deflected the responsibility for the fiasco. He admitted the Chesapeake was poorly prepared for battle when he left the dock that June morning. Her guns were not fitted properly and he had not exercised the crew much prior to leaving Hampton Roads, but none of those problems was his fault, Gordon said. He had not exercised his crew on the guns because until June 19 the Chesapeake had only twelve cannon mounted. Moreover, he did not have his full battery until the very morning the frigate sailed. Lastly, the final decision on whether to sail was Commodore Barron’s, not his, Gordon said, and the commodore should have easily seen the poor state of readiness on the vessel.25 “Yes, gentlemen,” said Gordon,

if I had detained the ship but one second after she was able to cross the Atlantic, and have so reported, I should have been called to a severe account for it. My accuser would then have said, all this work was not the business of half an hour and might as well be done as you were crossing the Atlantic with but little else to do. Thus I am placed between Scylla and Charybdis. For reporting the ship ready, I am censured; for detaining her longer when she was ready I certainly should have been censured. The alternative I adopted in this situation, while it disproves the charge [of negligence], was that alone which I could safely adopt.26

The trial could have cost Gordon his career. Instead, the brunt of the blame fell on Barron. The court found Gordon guilty of negligence for not having the Chesapeake ready for battle but sentenced him only to a private reprimand.27

The incident did little to sidetrack Gordon’s career. If anything, it made him more attentive to detail than ever before. It also further ingrained in him a hatred of everything English. For the second time in his life, an authority figure, this time Commodore Barron, had let him down and left him open to ridicule. Just as it had been with his father, he saw the British as the root cause.

Following his court-martial Gordon received command of the brig Syren with orders to transport a diplomat to France on a “special mission.” On the warship’s arrival, the French, borrowing a page from the British, demanded to board her to search for alleged deserters. Gordon refused and ordered his crew to clear the brig for action. The French backed down.28 Paul Hamilton, the new secretary of the Navy, “fully approved” of Gordon’s actions and tagged him for higher command, saying Gordon had helped restore public faith in the Navy by standing up to the French.29 Gordon’s hatred of the English and his propensity to blame them for any setback, however, continued to shape his life.

Three months after the Chesapeake incident, in November 1807, Gordon resorted to pistols to gainsay the claim he had unfairly jettisoned the blame for the disaster onto James Barron. The duel was against a distant cousin of Barron’s, a Dr. Stark. Under the terms of the duel, if either man fired before the other, the other duelist and his second could return fire. After four missed shots, Stark fired early on his fifth, missing Gordon. Gordon’s second, Lt. William Crane, immediately fired, hitting Stark in the arm. Stark’s second then stepped in and challenged Gordon and winged him in the arm. The wound had no effect on Gordon’s service; nor was it the last time Gordon would fight to defend his actions on the Chesapeake.

![]()

Politically, Alexander Hanson was Gordon’s opposite—passionately against war with Britain. Hanson was born on February 27, 1786, in Annapolis, the grandson of John Hanson, the first president of the Continental Congress. He graduated from St. John’s College in Annapolis in 1802 with a law degree and practiced as an attorney for six years. His political views were well known in the state capital, and he soon became a leading voice among Maryland’s Federalists.

![]()

In 1808 he began publishing the Federalist Republican, a highly partisan newspaper that quickly drew the attention and ire of federal officials. In one of its first issues Hanson wrote a biting editorial condemning the Embargo Act. A year later he again drew fire when he wrote a series of articles called “Reflections” in which he accused President Madison of ignoring Britain’s attempts at reconciliation, a common theme among Federalists. Britain, Hanson said, did not want a second war, nor could it afford to lose access to American raw materials. It had offered—and paid—reparations for the attack on the Chesapeake and had begun looking at ways to either modify or repeal the Orders in Council to answer America’s demand for access to European ports. The British also knew of land-hungry Americans’ designs on Canada as well as the strong antiwar movement in New England. Although England did not see America as a powerful enemy, any conflict that would divert resources from its war against Napoleon was something Britain wanted to avoid.

Federalists were quick to point out Britain’s willingness to negotiate. They were just as quick to blast Madison and congressional “war hawks” for their increasingly belligerent tone. On January 1, 1810, Hanson penned an editorial about the Chesapeake-Leopard incident in which he ridiculed the administration, and Democrats in general, for their anti-British stance and their refusal—as Federalists saw it—to see reality: “Shall we go to war with England because she protests . . . and refuses to sanction our encouragement of British seamen to desert . . . these men, if we recollect right, were encouraged to desert from their ships . . . were paraded about the streets of Norfolk in defiance of and in the presence of their own officers, and their existence on board the Chesapeake was formally and officially denied.”30

The deep division in Maryland politics continued right up to the declaration of war. When Madison sent his declaration to Congress, six of Maryland’s nine representatives, all Democrats, voted in favor. The state’s two senators were divided. Samuel Smith of Baltimore, the former secretary of the Navy, voted for war; Philip Reed of the Maryland Eastern Shore, a Federalist, voted against it.31

Two days after the declaration of war, on June 20, 1812, Hanson wrote a scathing editorial condemning the war and laying out the roadmap for Federalist opposition.

Thou hast done a deed whereat valor shall weep. . . . As the consequences will soon be felt, there is no need in pointing them out to the few who have not the sagacity to apprehend them. Instead of employing our pen in this dreadful detail, we think it more apposite to delineate the course we are determined to pursue as long as the war shall last. We mean to represent in as strong colors as we are capable, that it is unnecessary, inexpedient and entered into in partial, personal and as we believe motives bearing upon their front marks of undisguised foreign influence, which cannot be mistaken. We mean to use every constitutional argument and legal means to render as odious and suspicious to the American people, as they deserve to be, patrons and contrivers of this highly impolitic and destructive war, in the fullest persuasion that we shall be supported and ultimately applauded by nine-tenths of our countrymen, and that our silence would be treason to them. We detest and abhor the attempts by faction to create civil contest through the pretext of a foreign war it has rashly and premeditatedly commenced and we shall be ready cheerfully to hazard everything most dear, to frustrate anything leading to the prostration of civil rights, and the establishment of a system of terror and proscription announced in the Government paper at Washington as the inevitable consequence of the measure now proclaimed. We shall cling to the rights of freemen, both in act and opinion, till we sink with the liberties of our country or we sink alone. . . . We are avowedly hostile to the presidency of James Madison, and never will breathe under the dominion, direct or derivative, of Bonaparte, let it be acknowledged when it may. Let those who cannot openly adopt this confession abandon us; and those who can, we shall cherish as friends and patriots worthy of the name.32

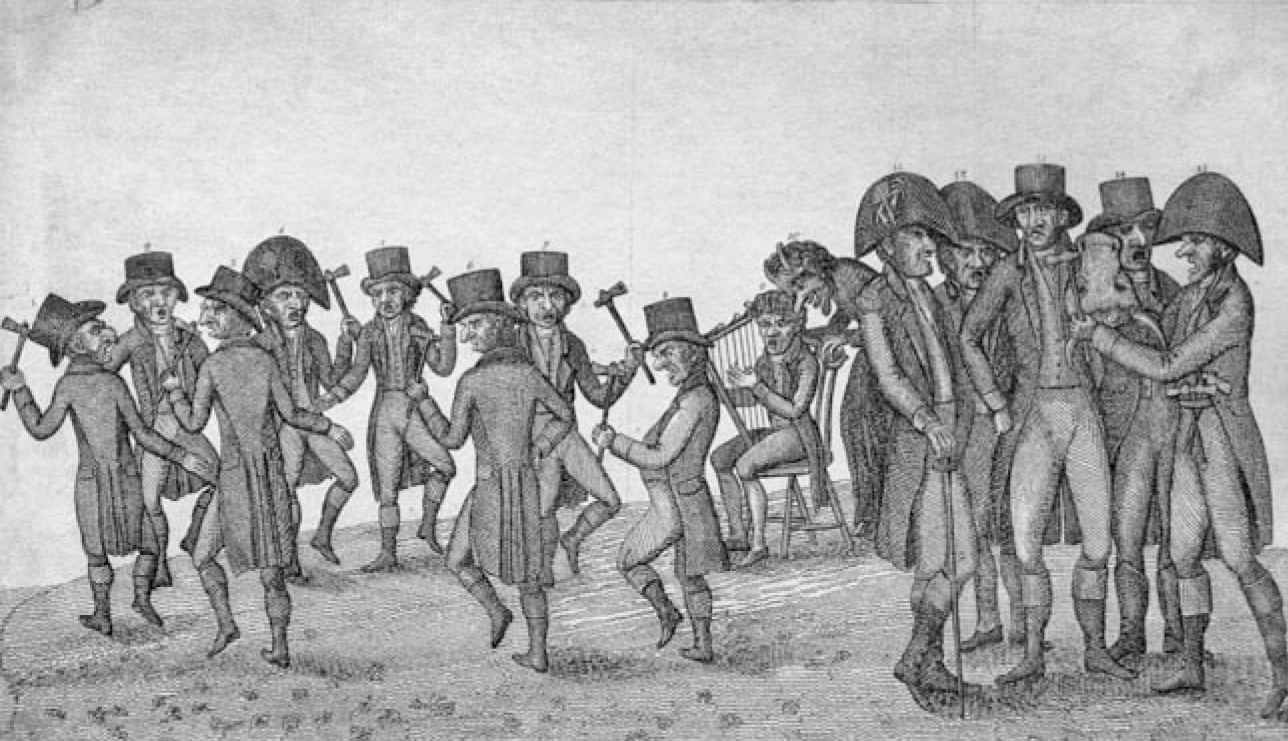

The editorial was the match that touched off a three-day firestorm in Baltimore as mobs took the debate over the war into the streets.

The Federalist Republican was based in downtown Baltimore. Two days after Hanson’s editorial appeared, a mob of Democrats gathered outside the newspaper’s office. Shouts of indignation quickly escalated to rock throwing. The mob smashed the windows, broke down the doors, and rushed in to destroy the printing press and set the building on fire. Local officials who responded to the disturbance did nothing to stop them.33

Hanson arrived at the ruins of his office the next day. Far from silencing the Federalist mouthpiece, the mob attack emboldened Hanson. He moved his newspaper office to Georgetown, in Washington, D.C., and made plans to start publishing once more. It took him roughly a month to get everything he needed, during which time anti-Federalist sentiment grew ever stronger in Baltimore.

Hanson opened a new office in Baltimore on July 26 in the Charles Street home of Jacob Wagner, one of his partners and a leading Baltimore Federalist. Wagner had vacated his house soon after the mob sacked the newspaper office, leaving his furniture behind, and agreed to lease the house and its contents to Hanson.34

The day he opened his office, Hanson released his first newspaper issue since June. He once more attacked the Democrats, blaming them for the destruction of his first office. He also railed against rival newspapers for fomenting the attack and heaped insults on the city officials who had done nothing to stop the mob on June 22, a group that he said included Mayor Edward Johnson, the city’s chief magistrate, and the police chief. He also slammed the mob that attacked his office, calling the rioters mindless tools of Democratic politicians.

![]()

The inflammatory editorial elicited an immediate response. A mob formed in Fells Point, on the city’s waterfront, and marched to Charles Street. They arrived at the Wagner house around 11 p.m. to find that Hanson was not alone; he had enlisted the help of several other Federalists to protect his new office. At first there were nine men, including former Continental Army generals James M. Lingham and the famed Henry “Light Horse Harry” Lee. Others included militia captain Richard Crabb, Dr. P. Warfield, Charles J. Kilgour, Otho Sprig, Ephraim Gaither, and John Howard Payne. According to those in the house, “Several others were to have gone, but were prevented; and on the night of the attack, the party was joined by three other volunteers from the county, who were not fully apprised by Mr. Hanson, of his determination, but received their information in confidence from others—Major Mesgrove, Henry G. Gaither, and William Gaither. On the evening of the attack, they were joined by about twenty gentlemen living in Baltimore, one or two only of whom were invited to the house by Mr. Hanson.”35 The defenders were determined to “meet force with force. . . . Reliance upon the civil authority they early perceived to be fruitless, for on application to the Mayor by the owner of the house, he peremptorily declined all interference and left town, as it was understood, to prevent his repose from being disturbed.”36

As the mob converged on the house, Hanson and his supporters brandished firearms. The mob responded with a fusillade of rocks. Subsequently, “an attempt was made to break down the street door, which was at length actually broken and burst open. All these acts of violence were accompanied by loud and reiterated declarations by the mob of a determination to force the house, and expel, or kill all those who were engaged in its defense.”37

Hanson and the others built a barricade of chairs and other furniture and prepared for the worst. Retreating to the second floor, they fired a volley over the heads of the rioters that sent them scurrying. The mob soon returned, however, with a Dr. Gale at its head. Gale exhorted the crowd to attack the house once more. With Gale in the lead, a number of rioters charged. The moment they crossed the threshold, Hanson and his men opened fire, killing Gale. The rioters returned fire and Ephraim Gaither dropped to the floor with a severe wound.

Just as the mob was about to charge again Mayor Johnson arrived with a group of militia. The mayor attempted—halfheartedly—to convince the mob to retire, but his words met with a chorus of boos and jeers. Johnson then asked Hanson and his men to surrender into his custody, promising he would protect them and remove them to a place of safety. By then it was 6 a.m. on July 27, and the standoff had gone on for nearly seven hours. Hanson and the others agreed to Johnson’s plan. They left the house under escort and walked to the jail.38

Later that day, the Democratic Baltimore Whig printed a caustic attack on Hanson in which it called him and the others in the house “murderous traitors” who should have been put to death. The editorial sparked off more rioting, and a mob headed for the prison. The party of militia Mayor Johnson had left to guard the jail was no longer on duty because the local commander had ordered the armed men to return to their homes. “The dismissal of the militia was instantly made known to the mob at the jail . . . and they regarded it, as was natural, as the signal for attack.” The mob stormed the jail and began battering down the doors to the cells that housed Hanson and his supporters. It took the rioters fifteen minutes to either knock down the doors or convince the jailor to unlock them—no one is quite sure which. Once they gained access to Hanson and his men, the mob dragged the Federalists outside and began to beat them. Hanson suffered a number of broken bones while Lee, a hero of the Revolutionary War, suffered so many blows that he remained an invalid until his death in 1818. James Lingham died of multiple stab wounds. In all, the mob beat a dozen Federalists, killing one and maiming the others.39

Federalists in Baltimore likened the riots to the worst excesses of the French Revolution, but Baltimore juries refused to convict any of the rioters. City authorities, however, indicted Hanson for manslaughter in the death of Dr. Gale, claiming Hanson had provoked the riots and he and his followers deserved the treatment they received. Hanson’s lawyer had the trial moved to the Federalist stronghold of Annapolis, where a jury acquitted Hanson of any wrongdoing.40 The “Baltimore Riots,” as newspapers dubbed the street battles between Hanson and the mob, shocked many in Maryland and deepened the rift between Federalists and Democrats in the state.

The rift the riots caused lingered throughout the war and had lasting effects on both Gordon and Hanson. The two met face-to-face just once—in a duel. Two years before the riot, Hanson, in his “Recollections” editorials, had claimed Barron and Gordon were directly to blame for what in 1810 seemed like an inevitable war with England. The two officers had willfully ignored the fact that the crew of the Chesapeake included many British nationals, hoping to precipitate an attack. The article incensed Gordon, who immediately challenged Hanson to a duel. The two met January 10, 1810, at the dueling grounds in Bladensburg, Maryland.

Hanson was a crack shot and, as a result of his vitriolic writings, an experienced duelist. Gordon had fought a duel only once before—back in 1807, when he missed his opponent four times. Hanson had the better aim and shot Gordon in the abdomen; Gordon’s shot missed Hanson altogether. The wound nearly killed Gordon. He was bedridden for more than a year, and only in March 1812 was he able to move around again, although he never completely recovered.41 Nevertheless, he assumed command of a small, ad hoc naval force somewhat grandly called the “Baltimore Squadron” in May 1812, just a month before the declaration of war.

When the news of the declaration reached Baltimore, Gordon wrote to his friend John Bullus about his burning desire to finally get back at the British and “send in a few large British prizes this summer.” Above all, Gordon told Bullus, he wanted to join with Stephen Decatur, Isaac Hull, and his close friend James Lawrence in commanding a frigate. “To be among them is the most ardent desire of my soul,” he said.42 He never would, and although he was frequently near the scene of battle, Gordon never engaged an English warship. He finally got to sea just as the war came to an end. His wound continued to plague him, and he died while on station in the Mediterranean on September 6, 1816.43

Hanson lived only slightly longer. He won election to the U.S. House of Representatives as a wave of Federalist sympathy swept through Maryland and served in the House from 1813 to 1816 and then in the Senate from 1816 to 1819. He never fully recovered from the injuries he suffered in the Baltimore Riot, and he died in 1819 at the age of thirty-three.44

Ultimately, the reasons behind the conflict that had brought the two men together mattered little. The gulf between Federalists and Democrats would continue to plague Maryland, and to a lesser extent Virginia, when the war entered the Chesapeake.