![]()

THE DAY’S EXERTIONS had taken a heavy toll on the British army that was now poised to enter Washington. The battle at Bladensburg ended around 5 p.m., when the heat of the day was still at its fiercest. Many British soldiers simply collapsed from heat exhaustion on the fields they had recently conquered. Ross allowed his men to rest for three hours. The soldiers buried their dead, tended their wounded, and readied for the final push.1

In the city, people grabbed whatever belongings they could carry and joined the bedraggled stream of militia and fellow citizens running from the city. First lady Dolley Madison oversaw the removal of belongings from the executive mansion. She was particularly insistent on saving the full-length portrait of George Washington by Gilbert Stuart. The first lady was a formidable presence. Unlike nearly everyone else in Washington, Dolley Madison remained calm, almost defiant, toward the impending occupation of the nation’s capital. She carefully managed the packing of the president’s valuables and removed as much silverware as she could carry and her personal copy of the Declaration of Independence. Then she took one look back at her home and boarded a carriage that would take her to Virginia and relative safety.2

Capt. Thomas Tingey, commander of the Washington Navy Yard, had no idea whether he should leave or remain at his post.3 The navy yard was full of supplies and housed two warships—the 44-gun frigate Columbia and the new sloop of war Argus—that were nearing completion. Three barges—two 75-foot boats and one 50-foot vessel—also bobbed at anchor. The workshops at the yard had sails, ropes, and lumber—everything needed to build and equip warships. Tingey had orders to ensure that none of the supplies fell into British hands.4 Just past 4 p.m. Tingey saw a portion of the Eastern Branch bridge blown up into “splintery fragments” as Captain Creighton and his small party of sailors blew up the second of the three bridges over the Eastern Branch leading to the city. Clerk Mordecai Booth volunteered to act as a scout to determine where the British were and to provide warning if they headed for the navy yard. Tingey agreed, and Booth rode off toward Bladensburg.5

Ross began rousing his tired soldiers as the last rays of sunlight faded. The British commander left his first two brigades, which had seen the bulk of the combat during the afternoon, at Bladensburg, where they could continue to rest and follow once Ross had secured the city.6 He pushed forward with Col. William Patterson’s third brigade of Patterson’s 1st Battalion, 21st Foot, and the Royal Marine battalion under Lt. Col. James Malcolm. Ross himself led an advance guard of two hundred men to the outskirts of the city. He met no resistance, nor did anyone answer his calls for parley as he apparently sought someone who could officially surrender the city.7

As Ross and his advance party approached a large, stately house within view of the Capitol, a group of unseen gunman opened fire on the British, killing one man and wounding two. The volley dropped Ross to the ground when a round killed his horse. Ross immediately ordered a squad from the 21st to envelop and attack the house, which had once belonged to Albert Gallatin. Although the soldiers found the house empty, Ross ordered them to burn it down as a warning to those still in the city.8 The flames were the first of the evening in the capital that the British started, but not the first flames. A glow from the southwest signaled the destruction of the Washington Navy Yard.

Tingey waited until Mordecai Booth returned to the navy yard around 8 p.m. with word that the British were in the city before he gave the order to set the yard ablaze. He and the few men left at the yard lit fuses leading to warehouses, sail lofts, and rope lockers. Tingey raced along the dock, setting the fuses to the Columbia and the Argus. Fire licked at every bit of wood in the yard, adding to the growing glow in the night sky. Within minutes the navy yard was burning brightly. The frigates New York, Boston, and General Greene were also at the yard, essentially rotting at the wharf. All three went up in flames, adding to the heat.9

Ross and Cockburn led their column toward the Capitol, which was clearly visible in the fading light atop its hill. Although it did not yet have a distinctive dome—that would not be built for another fifty years—the building was the centerpiece of the still-new city. Soldiers broke down the doors and Lt. James Scott entered the building. “It was an unfinished but beautifully arranged building,” Cockburn’s aide reported. “The interior accommodations were upon a scale of grandeur and magnificence little suited to pure Republican simplicity. We might rather have been led to suspect that the nation, whose councils were held beneath its roof, was somewhat infected with an unseemly bias for monarchial splendor.”10

That “grandeur” made perfect kindling. Soldiers and Royal Marines dragged furniture, books, papers, and anything else that would burn into large piles and set fire to them. The Library of Congress, then housed within the Capitol, provided even more fuel. When the flames had completely engulfed the Senate and House wings, the British moved to the Supreme Court. The court building was still new and had little furniture, but the redcoats made do. They hauled in furniture from other rooms and made another pile of kindling before setting it alight. The fires completely gutted but did not destroy the Capitol.

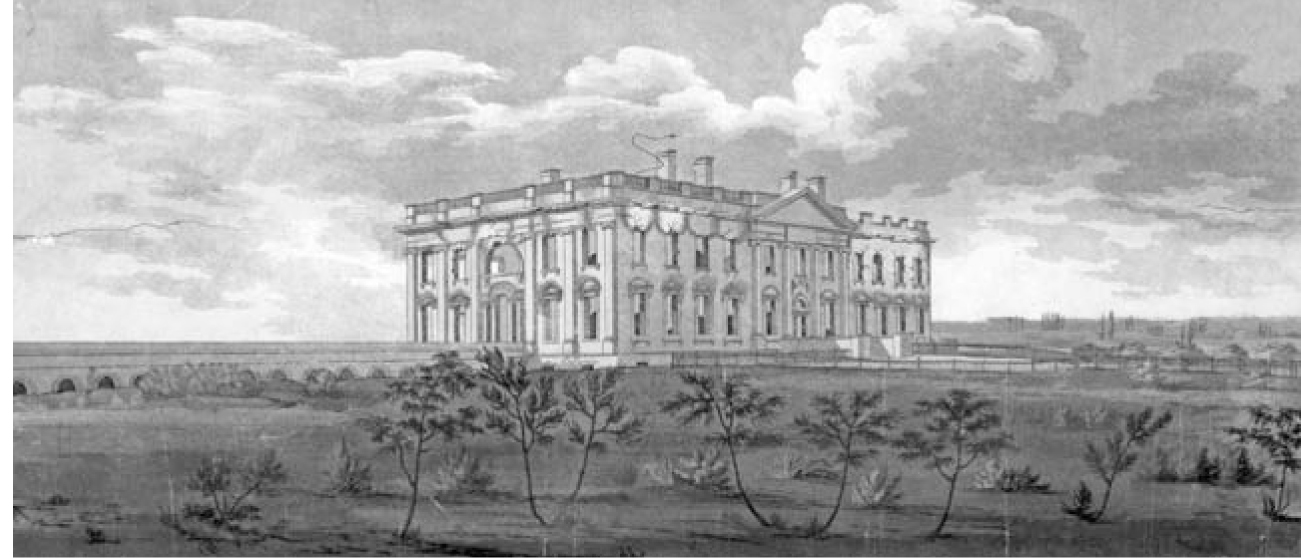

After setting fire to the Capitol, the British troops under Ross and Cockburn marched to the President’s House, a mile down Pennsylvania Avenue from the Capitol. The executive mansion was eerily quiet when they entered it sometime after 10 p.m. In the dining room, the table still held the sumptuous feast Madison had planned to serve that evening. Famished after the day’s exertions, the British gorged themselves. “Never was nectar more grateful to the palates of the gods than the crystal goblet of Madeira and water I quaffed at Mr. Madison’s expense,” Scott recalled.11

After eating, the British fanned out through the house to find souvenirs. Cockburn snatched up a cushion and a hat he believed belonged to President Madison. Someone took an ornate medicine chest. Scott grabbed clean shirts from the president’s bedroom while an officer from the 85th Foot spirited away an ornate sword. Another “saved” a portrait of the first lady. Their rummaging finished, the British turned to the business of setting the house on fire. As they had done at the Capitol, the redcoats used drapes, papers, and furniture for kindling. The fire quickly moved through the house, gutting the building.12

Cockburn’s next target was the Treasury Department building, which stood next to the executive mansion. Soldiers smashed the windows of the brick edifice then tossed in torches. Flames quickly engulfed the building. Cockburn wanted to continue the destruction by burning the War Department and State Department buildings, but Ross scuttled the idea, saying the soldiers and marines needed to rest. The British bedded down for the night with plans to continue the destruction of the city in the morning, although the vandalism continued.

When Cockburn passed by the offices of the National Intelligencer, he wanted to burn the building but stopped when neighbors begged him not to do it. Instead Cockburn ordered a party of sailors to literally tear down the building by passing ropes through windows and around the walls. Neighbors again pleaded, claiming the building did not belong to the newspaper’s owner and the British would be destroying private property. Cockburn again relented, and then ordered soldiers to remove all the furniture, type, and presses and burn them in the street.13 The redcoats finally settled down to sleep after they set the offices of the State Department on fire.

Soon after sunrise the redcoats went back to work. A party of sailors went to the War Department building and very quickly set it ablaze. Lieutenant Scott led a detail to the Tench Ringgold, John Chalmers, and Heath and Company ropewalks, private businesses that supplied rope and cordage to the military. The huge, long buildings contained bundles of hemp, which the British covered with tar and used as fire starters. Within thirty minutes the ropewalks were brightly burning.14

![]()

A column of eighty men marched to the Greenleaf Arsenal, where they destroyed cannon and shot. They spiked unmounted artillery barrels and tossed them into the Potomac along with cartridges and grenades. The destruction went according to plan until the men came across 130 barrels of gunpowder, which they began tossing one by one down a well. A freak spark triggered a massive explosion that killed or injured nearly every sailor, Royal Marine, and soldier at the arsenal. Thirty men died, buried beneath tons of dirt and debris, and forty-seven more were wounded. The blast presaged an even bigger explosion, this one natural.15

Just hours after the explosion at the arsenal, a storm blew in from the west. Summer thunderstorms were normal, but this storm packed tornadoes. Bolts of lightning lit the sky as the winds tore through the city, toppling trees, knocking over chimneys, and spreading terror. Rain came down in torrents, extinguishing any embers that remained from the fires and soaking exposed troops, who cowered in open fields. The storm raged for two hours. When it finally subsided, Ross and Cockburn determined their work was done and began to collect their troops on Capitol Hill. Just after nightfall the British began to leave the city, setting campfires first to make any American soldiers in the area believe they were still present. The British returned to their ships by marching first to Bladensburg, where they spent several hours resting before marching to Benedict to reembark.16 The invasion fleet spent two more days on the Patuxent before joining up with the Patuxent and Upper Chesapeake squadrons.

![]()

[Editor’s note: Stanley Quick created a daily diary for Royal Navy captain James A. Gordon describing his push up the Potomac River that coincided with Cockburn’s and Ross’ attack on Washington, D.C., and the subsequent American efforts to trap Gordon on the river on his return trip. Mr. Quick went into great detail about the British use of kedges and hawsers to literally pull their vessels up the Potomac as well as the numerous times the British grounded on shoals in the river. He provided no sources, although he did reprint the reports of the principal officers involved, from which his account apparently derives. The following is a condensed version of his chapter on Gordon.]

The same storm that hammered Ross’ troops as they left Washington lashed the squadron of Capt. James Gordon in the Potomac River. Gordon commanded one of the two diversionary forces that Cochrane set in motion when Ross set out for Washington. Gordon’s mission was to ascend the Potomac and either act in concert with Ross and Cockburn in reducing Fort Washington before attacking the capital city or act alone in running past the fort to attack Alexandria.

Gordon entered the Potomac in command of seven ships: his own 38-gun frigate, the Seahorse; Capt. Charles Napier’s 36-gun Euryalus; the bomb ships Aetna, Devastation, and Meteor; the rocket ship Erebus; and the tender Anna Maria. He started the one-hundred-nautical-mile journey toward Alexandria on August 17 and for a week worked his way up the river, dodging shoals, oyster banks, and sandbars. Each night Gordon placed a cordon of guard boats around his ships to prevent both attack and desertion.17 On August 24, the day Ross routed Winder at Bladensburg, Gordon and his squadron anchored off Maryland Point, about twenty-five miles south of Fort Washington. He was still preparing his ships to pass the shoals off Maryland Point when the storm struck.

“The squall thickened at a short distance, roaring in a most awful manner, and appearing like a tremendous surf,” Napier later wrote. The Potomac churned as the full force of the storm swept over the British ships. Lightning struck one of the guard ships of the Euryalus, sinking the boat. The Euryalus lost her bowsprit, jib boom, topmast, fore topgallant mast and foremast head, many sails, blocks, lines and running rigging. The Seahorse lost her mizzenmast and all of her cross trees and trestle trees. The Meteor grounded and lay on her side after the storm, losing her topgallant mast.18

![]()

After assessing the damage the following morning, Gordon was ready to abandon his mission and return to the Chesapeake. He believed the Euryalus was beyond repair, and the damage to his other ships was clearly extensive. His captains, however, assured him they could make the necessary repairs while under way, and Gordon agreed to continue. By the early afternoon on August 26 Gordon’s flotilla was again in motion, including the Meteor, which had been righted and pulled off the shoal with brute force.19 On August 27 the squadron arrived off Fort Washington.20

The fort should have presented a major impediment to Gordon’s so-far-unchallenged ascent of the river. On paper, at least, Fort Washington had a pair of 52-inch Columbiads, two 32-pounders, eight 24-pounders, five 18-pounders, and a collection of 12- and 6-pounder field guns. The magazine contained more than 3,000 pounds of powder, 899 cannon cartridges, several hundred rounds of grape and canister, muskets, flints, musket cartridges, and bayonets.21 What the fort’s commander, artilleryman Capt. Samuel Dyson, lacked was soldiers to man all that ordnance. Dyson had fewer than sixty men to work the more than twenty cannon at the fort and stave off a land attack.22 It was a nearly impossible situation.

As he retreated from Bladensburg on August 24, Winder, as commander of the military district that included Fort Washington, sent Dyson orders that “in the event of his being taken in the rear of the fort by the enemy,” he was “to blow up the fort and retire across the river.”23 Dyson apparently needed little urging. As the British squadron hove into view, he called a council of war with his officers to decide whether to fight or flee. In his official report Dyson claimed he had information that a two-thousand-man British brigade “was on their march to cooperate with the fleet.”24

Gordon ordered his mortar vessels to take up positions “just out of gunshot” from the fort at 5 p.m. At 6:30 the British lobbed their first shots. Gordon planned to shell the fort all night and attack with his frigates on the morning of August 28. Dyson, however, sped up that timetable. Within minutes of the first bombs landing, Napier, on the Euryalus, reported, “The garrison, to our great surprise, retreated from the fort.” Dyson had his men spike all the cannon and set a fuse in the magazine. At about 8 p.m. Fort Washington exploded.25

“We were at a loss to account for such an extraordinary step,” Napier later said. “The position was good, and its capture would have cost us at least fifty men, and more, had it been properly defended; besides, an unfavorable wind, and many other chances, were in their favor, and we could only have destroyed it had we succeeded in the attack.”26

The next morning Gordon sent ashore a party of sailors and Royal Marines, who wrecked the carriages of the spiked cannon and destroyed everything the explosion had missed.27 Dyson faced a court-martial for his actions and was eventually cashiered out of the Army.28

Gordon next set his sights on Alexandria. He set sail after completing his work at Fort Washington, and at 9 p.m. that night the bomb ship Aetna anchored off the town. Her captain, Lt. Thomas Alexander, reported finding several merchant vessels either dismantled or scuttled in the harbor. Officials in Alexandria were quick to seek terms from the British and offered to surrender the city. Gordon arrived with the remainder of the squadron at daylight on August 29 and dictated harsh terms: Alexandria and its merchants were to deliver to the British “all naval and ordnance stores, public or private”; surrender “all shipping, and their furniture must be sent on board by the owners without delay”; refloat the vessels either scuttled or dismantled; and, finally, hand over “merchandise of every description.”

Gordon spent the next two days stripping Alexandria of anything and everything of value, including slaves. His sailors raised the scuttled vessels so that Gordon could use them to haul off his booty. The British took twenty-one prize vessels—schooners and sloops of varying sizes—and stuffed them full of the material they took from Alexandria. On September 1 Gordon received information that the Americans were establishing batteries on both sides of the Potomac to oppose his return to the Chesapeake. While protecting private property as per the agreement, Gordon destroyed any military supplies and goods he could not load and, with his prize ships in tow, began to make his way back down the river.

![]()

The surrender of Alexandria without a shot upset Americans almost as much as the burning of their capital. Howls of anger arose, and Navy secretary Jones turned to three naval heroes who had just arrived in Washington to prevent either a second attack on the capital or an attack on Georgetown. Oliver Hazard Perry, David Porter, and John Rodgers were all in Baltimore at the end of August. Perry was assigned to ready the new frigate Java for sea, while Porter and Rodgers were tasked with assisting in the defense of Baltimore. Jones ordered the three captains to Washington to take on Gordon’s squadron, with Rodgers, the senior officer, in overall command.29 Jones asked Rodgers to rush to Washington with “650 picked men or more” who were to attack the British ships in small boats.30 He ordered Porter to the Virginia side of the river to take command of a party of sailors and Marines and five 18-pound guns.31 Perry received orders to set up a battery on the Maryland side of the Potomac.32

For the next week the Americans engaged the British squadron in a running battle from just below Alexandria down to Kettle Bottom Shoals. Porter twice came close to sinking enemy vessels when his big cannon blasted the brig Fairy and the rocket ship Erebus while both ships were guarding other vessels in a convoy that had run aground. Rodgers, who arrived in Alexandria on September 1, twice attempted to use fire ships to destroy the enemy flotilla. On September 3 Rodgers led fifty men in four boats in an effort to take both the bomb ship Devastation and a prize vessel. Rodgers had three fire ships, but boatloads of Royal Marines arrived from the squadron in time to beat off the attack.33

Porter had a chance the same day to attack the Erebus and the Euryalus when the British attempted to disrupt construction of his battery at White Horse, Virginia. Porter’s Marines and militia drove off a landing attempt while his big guns pounded the enemy rocket ship with grape and canister. Rodgers made a second attempt to attack with fire ships that night, but again without success.34 By September 8 the convoy had cleared Kettle Bottom Shoals, and the last chance to intercept the British in the Potomac was gone. The weeklong ordeal cost the British seven dead and thirty-five wounded, most of them on the Euryalus, which bore the brunt of Porter’s barrages on September 3.35

Gordon rejoined Cochrane’s main fleet on September 9, and the combined force set sail for Kent Island, where Cochrane planned to meet Sir Peter Parker and the second diversionary force before setting out for the ultimate target, Baltimore.

![]()

[Editor’s note: Stanley Quick wrote at length about the events surrounding Parker’s brief forays along the Eastern Shore of the Chesapeake. He went into great detail about the lives of the owners of the farms the British burned and even named the slaves who ran away to join the British. The following is a greatly condensed version of Mr. Quick’s account of the small battle at Caulk’s Field.]

Capt. Peter Parker, commander of the second diversionary force, and his ships, the frigate Menelaus and the tenders Mary and Jane, arrived off Rock Hall on the Eastern Shore on August 27 after reconnoitering Baltimore Harbor. Parker placed buoys and tested the city defenses, battling several gunboats before heading toward Annapolis. The Mary swamped during a storm, carrying with her muskets and ammunition.36 After anchoring off Poole Island, Parker reported to Cochrane that he observed “the Enemy’s Regular Troops and Militia in Motion along the whole coast,” and that they “had taken up a strong Position close to a large Depot of stores.”37

The storehouse was actually the farm of Henry Waller. When he saw the Menelaus at anchor off the farm, the local militia commander, Lt. Col. Philip Reed, marched three companies of the 21st Maryland militia to the farm to contest any landing that might occur. The presence of the militiamen convinced Parker the farm harbored war materiel, and “this induced me instantly to push on shore with the small arms men and Marines.”38 He dispatched all of his ships’ boats and covered the assault with gunfire from the Menelaus. Reed, who had stationed his men along a fence on the farm about eight hundred yards from the main house, decided not to contest the landing in the face of superior firepower. The British landed, took possession of the farm, and set fire to all of its buildings. Reed’s militia opened fire as they were leaving and wounded an officer.39

Waller recovered the casing of a spent Congreve rocket the British fired at his home that is now on display at the Fort McHenry museum. Years later, with the help of their attorney, Francis Scott Key, the family received full compensation from the federal government for the loss of their home.40

On the morning of August 30 Parker decided to make another landing, this time with the goal of rooting out the militia. Parker was particularly glum that day because his cocked hat had fallen overboard while he was inspecting rigging on the Menelaus. “My head will follow this evening,” he remarked to those around him. He prepared his will, destroyed his personal papers, and acted very much like a man going to his death.41 At 9 p.m. a force of 104 armed sailors and 30 Royal Marines embarked, bringing with them a Congreve rocket launcher.42

The boats moved with muffled oars under the protection of the Jane. On landing just after 11 p.m., Parker divided his sailors and Royal Marines into two sections and began to move inland. The advance guard moved out rapidly and within a quarter of a mile came upon three mounted pickets under a large tree, fast asleep astride their horses. The seamen approached within ten paces, took deliberate aim, and—foolishly breaking silence—fired, hitting neither man nor horse. The pickets, startled awake, fired back and headed off into the nearby woods. One of the fleeing sentries fired a pistol, and the British could hear answering volleys as the sentries alerted the militia.43

Nevertheless, Parker decided to press on. He had another chance to use secrecy when his guide told him he had arrived on the outskirts of the American camp and could use a nearby wood to come up on the rear of the militia. Parker, however, decided to launch an all-out frontal attack. He led his men into a defile of felled trees that allowed five men to march abreast. The defile led right to Caulk’s Field. The British nearly caught the Americans by surprise because Lieutenant Colonel Reed was expecting Parker to attack a nearby farm, not his camp. A sentry warned the militia just in time, and Reed set his men to greet the invaders.

He posted a company of twenty riflemen about sixty yards from where the defile met the field and established his main line two hundred yards behind the riflemen. His force numbered around three hundred men and included three artillery pieces.44 Reed completed his defensive preparations at 1 a.m. on August 31, just as Parker ordered his column to move out from the defile. The rash British advance showed the contempt Cockburn had instilled in his officers for militia. As the head of the column emerged, the American riflemen opened fire with a well-aimed and rapidly delivered fusillade. Seven attackers were hit. The first man killed carried the staffs for the rockets, which prevented the British from using them in the battle.45

![]()

Unable to back down or turn aside, the British had no option but to charge. They burst into the “open field” surrounded by a thick wood. At the summit of a gentle slope the three American fieldpieces pointed directly at the opening of the defile. As the British surged forward, Reed raced along the line and sent the riflemen to his right flank. The British headed right at the center of the line. A volley from the cannon killed a midshipman, forcing the British to change tactics.46

Lt. Henry Crease, second officer on the Menelaus, led his seamen and attacked Reed’s right while Parker, leading the Royal Marines, tried to turn the left flank. The marines fired with great speed, advancing at the double quick to close with the militia and finish the battle at bayonet point. The American left began to bend but did not break. At this instant Parker, who had been cheering on his marines with his ornate Turkish sword, suddenly collapsed into the arms of one of his officers, saying, “I fear they have done for me. . . . [Y]ou had better retreat, for the boats are a long way off.” A bugle sounded and the British backed off, a group of Royal Marines carrying their dying leader on their shoulders. Parker died from a thigh wound that cut his femoral artery.47

The British retreated to their boats, leaving the field in Reed’s hands. They suffered 11 dead, 24 wounded, and 6 missing out of a force of 136 men. The Royal Marines took the brunt of the casualties, with 7 dead and 11 wounded out of 32 officers and men.48 Reed’s force suffered just 3 wounded.49

The British flotilla rejoined Cochrane’s main fleet. After considering several options, including an attack on Rhode Island, it was decided to “make a demonstration” against Baltimore. The fleet set sail for the Patapsco River and Baltimore.