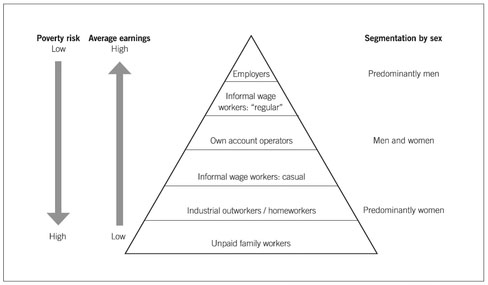

Figure 20.1 WIEGO model of informal employment: hierarchy of earnings and poverty risk by employment status and sex Source: Chen (2012: 9).

Prospects for well-being

Elizabeth Hill

The activities and processes that constitute what we call ‘the economy’ are typically characterized in formal terms based on strict definitions. This is true across mainstream and heterodox traditions alike. Many of these definitions and frameworks of analysis, however, sideline a large number of activities that contribute directly to the process of capitalist provisioning and human well-being.

Feminist and environmental approaches to economics have highlighted some of these problems and challenged orthodox conceptions of the economy in their work on reproductive labor, care, nature, and the environment. In this literature, mainstream economic ideas of ‘value,’ ‘work,’ ‘production,’ and ‘reproduction’ are contested and exposed as blind to essential economic processes and relations of capitalist accumulation (Mies 1986; Waring 1988; Daly & Cobb 1989; Beneria 2003). In the field of development economics, orthodox theories of capitalist development and economic growth in post-colonial economies have been challenged by studies on the livelihood strategies practiced in the new urban centers of the developing economies in Asia, Africa, and Latin America. These studies have produced a rich body of theoretical and empirical scholarship that focuses on economic activities that do not conform to mainstream understandings of the regular or ‘formal economy’

Scholars coined the concept ‘the informal sector’ to help them analyze these alternative economic activities and their relationship to the mainstream capitalist economy (Hart 1973). Since the 1970s scholarship on the informal sector and processes of economic informality has burgeoned as economic development in the post-colonial world has not produced widespread formalization of the economy and informal economic activities have become entrenched. Informality is also a nascent feature of the contemporary Chinese economy and other ex-communist states, and a growing phenomenon in many post-industrial economies, sparking the interest of academics outside the development economics community (Leonard 1998; ILO 2013a).

Scholars from orthodox and some heterodox traditions have contributed to the theoretical literature on informality,1 trying to explain the prevalence of informal economic activities and their contribution to employment, economic growth, and development. In recent years, scholarship on the reproduction and extension of informal employment and production relations has been linked to global processes of capital accumulation (Carr & Chen 2002; Chen 2006; Meagher 2013). However, expectations about the prospects of the informal economy differ: mainstream economists highlight the entrepreneurial potential of informal workers and their informal enterprises, while many heterodox scholars focus on the dynamics of exploitation and underdevelopment, which, they argue, define the informal economy. This chapter will explore the theoretical tensions that shape the debate on the informal economy and its role in economic and human development. It begins with a short account of the evolution of the informal economy as an analytical idea and the debates around definition and measurement. The chapter then explores the social relations that structure the informal economy including the relationship between informality, gender, and poverty. The final section provides a short analysis of the global policy debate about how economic security and well-being of informal workers can be improved. This is the critical issue given the prevalence of the informal economy around the world and its direct association with socio-economic insecurity and poverty.

The informal economy refers to economic activities, processes, and practices that are not organized according to the regular rules, customs, and norms of capitalist economic institutions. Instead, informal economic activities occur beyond the purview of the state and regulatory regimes. Informality within the economy was originally identified by economists working on theories of economic development and growth in the post-colonial era of the 1950s. The first theories of economic development were premised on dualistic models of the economy in which economic activities were divided into the ‘traditional’ and ‘modern’ sectors (Lewis 1954; Harris & Todaro 1970). Price incentives in the form of higher wages were expected to attract labor away from traditional economic activities and into the modern industrial sector. This shift in the allocation of labor out of marginal, unproductive, and survival-oriented activities and into formal processes of capitalist production would then provide the foundation for national economic growth (Lewis 1954). As labor relocated and capitalist economic development took hold in the newly independent nations in Africa, Asia, and Latin America, it was assumed the traditional, informal economy would slowly fade away and become an artifact of economic history. This has not occurred. Instead, economic informality has become a common and embedded feature of many developing countries, and is resurgent in some postindustrial economies.

Mainstream development economists were not only wrong about the transience of the informal economy, but also about the dynamism of informal economic activities, their contribution to livelihood and connection to the formal economy. Keith Hart’s (1973) study of Ghana was the first to challenge the underlying assumptions of orthodox dualistic approaches to economic development. Empirical data collected among urban migrants to Ghana’s capital, Accra, showed that many of the economic activities economists previously deemed ‘traditional’ or informal and hence marginal and unproductive constituted a dynamic and productive sector of the modern Ghanaian economy. Hart’s study established that inflation, low wages, and a surplus supply of labor in the urban labor market of Accra had led to the emergence of a high degree of informality in the economic activities of workers he defined as the ‘sub-proletariat.’ These empirical findings led to Hart’s coining of the ‘informal sector’ concept, based on an analytical distinction between workers employed in the ‘formal sector’ and those employed in the ‘informal sector’ of the economy.

According to Hart, the difference between the two sectors was the degree to which work was rationalized, controlled, and predictable. Workers recruited on a permanent and regular basis for fixed rewards were deemed to be part of the ‘formal sector’ and workers who were self-employed, unable to find work in the formal sector due to a lack of opportunities and training constituted the ‘informal sector’ (Hart 1973: 68). Hart found that workers in Accra were active participants in a range of informal economic activities that provided many of the city’s essential services, were productive, and generated growth and employment. Models of economic development, he argued, needed to recognize both informal and formal economic structures, and support the productive, employment, and growth-generating capacity of informal workers and their activities.

The ILO World Employment Program in Kenya was also studying the informal sector at this time, but from the point of view of the enterprise. The Kenya study differentiates between the characteristics of informal and formal enterprises2 and, similarly to Hart, concluded that the bulk of informal activities were productive, economically efficient, and profit making: “a sector of thriving economic activity and a source of Kenya’s future wealth” (ILO 1972: 5). The ILO’s focus on the employment and growth potential of informal enterprises challenged orthodox approaches to economic development and growth in post-colonial economies. While the dualists saw low productivity and residual survival-based strategies, Hart and the ILO saw productivity and innovation. They argued the state needed to change its approach to informal workers and their enterprises and instead of ignoring them, develop inclusive policies of economic support.

Hart and the ILO’s ground-breaking and upbeat studies of the informal economy as a hub of economic dynamism were disputed by many scholars working from a heterodox perspective. Drawing on Latin American dependency theory (Frank 1967) and world systems theory (Wallerstein 1974), micro-studies from across the developing world emphasized the structural nature of the relationship between informal and formal sector activities as one of dependence and exploitation (Leys 1973; King 1974; Obregon 1974; LeBrun & Gerry 1975; Breman 1976; Gerry 1978; Moser 1978; Davies 1979; Santos 1979; Portes et al. 1989). In these studies scholars argue that informal and formal economic activities are deeply integrated according to relations of structural exploitation which constrain the potential for growth and accumulation among informal activities. They conclude that, in a competitive global market place, it is the informal economy that provides the cheap goods and services that underwrite capital accumulation in the formal economy. Recent scholarship on global value chains has bolstered the appeal of this approach.

Contrary to this hypothesis is the work of scholars working in a socio-legalist tradition—an approach exemplified in the work of Hernando de Soto (1989, 2000). De Soto argues the informal economy persists and is becoming widespread because of the excessive transaction costs imposed on economic activities by ‘mercantilist-style’ government regulations and bureaucratic controls that serve the interests of wealthy elites and inflict excessive compliance costs on regular people wanting to make a living. According to this school of thought, bureaucratic constraints and high barriers to entry are the driver of expanded informality—the only logical, survival-based mass alternative form of economic organization. Legalists argue that governments should simplify the bureaucratic and regulatory system so informal workers can gain legal recognition and access to the productive resources that will enhance productivity and allow them to accumulate capital. This optimistic free market approach to the informal economy has been adopted by mainstream economic development institutions such as the World Bank and a number of governments in Latin America and Eastern Europe, who see private initiative and enterprise as the fundamental building blocks of economic development.

These competing approaches to understanding what lies behind the prevalence and recent growth in economic informality reflect different economic and ideological traditions. None of them, however, captures the vast heterogeneity that defines the informal economy. Informal work as a survival strategy has a long history in developing economies where formal jobs are rare. This is also becoming a strategy used in times of economic crisis such as the Great Recession of 2008 (Horn 2009). However, informal employment is not always the choice of the worker. Increasingly, informality is the choice of employers and companies wanting to avoid the regulatory costs associated with formally organized economic production and employment. Much of the current growth in informal wage labor is the result of formal jobs being informalized through processes of contracting out and the expansion of other non-standard production and employment relationships. The extension of global production chains and new trade relationships often rely upon competition between workers and can affect the shape of the informal economy and workers’ employment options (Standing 1999).

In the early twenty-first century, theoretical literature on the informal economy has taken a pragmatic turn with old ways of framing the debate giving way to more open, inclusive, and dynamic approaches that better capture the heterogeneity and dynamism of the informal economy across the development spectrum. These pragmatic responses are based on an acknowledgment that economic informality is not a historical anomaly but a ‘normal’ and regular feature of capitalist economies (Jutting & de Laiglesia 2009). It is now generally recognized that the informal economy provides employment for hundreds of millions of people around the world and that informal enterprises generate a significant amount of national Gross Domestic Product (GDP). It is also commonly accepted that the informal economy is integrated in complex ways into formal processes of production, distribution, and exchange, and that people who perform informal work are scattered across a myriad of occupations producing legal goods and services.

Within this more pragmatic approach informal employment has become the focus. This is captured in the ILO’s reformulation of informality as a continuum of economic relationships and activities organized according to the extent to which work is rationalized and employment is regulated. At one end of the continuum are highly formalized economic activities. At the other are those activities that are most informal (ILO 2002). Informal employment is problematized as unregulated, insecure, and mostly very poorly paid, with workers highly exposed to the risk of poverty. This approach has influenced policy makers who interpret worker vulnerability and the ‘gap’ in workers’ basic rights, legal protection, representation, and access to basic social security provisions as ‘problems’ in need of redress. In policy circles, this approach has culminated in the ‘formalization debate,’ which will be discussed in the final section of this chapter (ILC 2015).

Running parallel to the theoretical debate has been an international discussion about how to improve data collection on informal employment, the value of production in the informal economy, and its contribution to national economic growth (Charmes 2012). In 1993 the International Conference of Labour Statisticians (ICLS) passed a resolution on the informal sector to be included in national labor force and economic surveys. The definition focused on characteristics of the enterprise in which people worked, stipulating that:

These [informal] units typically operate at a low level of organization, with little or no division between labour and capital as factors of production and on a small scale. Labour relations – where they exist – are based mostly on casual employment, kinship or personal and social relations rather than contractual arrangements with formal guarantees. . . . Production units of the informal sector have the characteristic features of household enterprises. . . .

ILO 1993: Point 5

The definition provided a useful foundation but excluded a number of important economic activities including agricultural and related activities, households producing goods for their own use, domestic housework, care work, paid domestic work, and volunteer services. In 1997 the Delhi Group on Informal Sector Statistics was set up by the United Nations (UN) Statistical Commission to improve and develop the definition and data collection. This work culminated in a second resolution on the informal economy by the ICLS in 2003 and included an extended definition based on a conceptual framework that combines an enterprise-based concept of employment in the informal sector with a broader jobs-focused concept of informal employment. This expanded definition redefined the informal economy in terms of informal employment in which economic informality is determined by the level of protection and regulation of work, irrespective of the type of employment arrangement or whether the type of economic unit people operate or work for are informal enterprises, formal enterprises or households:

Employees are considered to have informal jobs if their employment relationship is, in law or in practice, not subject to national labor legislation, income taxation, social protection or entitlement to certain employment benefits (advance notice of dismissal, severance pay, paid annual or sick leave, etc.).

ILO 2003: 51

The expanded definition includes casual, short-term, and seasonal workers, own-account workers engaged in their own informal enterprise; employers in their own informal sector enterprises; contributing family workers; members of informal producers’ cooperatives; employees holding informal jobs; and own-account workers producing goods for their household use. It also includes workers in formal sector enterprises who are not entitled to basic protection and social security.

Improved statistical guidelines and increased interest in the informal economy by governments and policy makers have led to a rise in the collection and reporting of both the size of the informal economy and its contribution to national growth. A recent study by Vanek et al. (2014) shows that informal employment is growing. In developing economies, informality is expanding into new and unexpected places—including the formal economy. In India, for instance, growth in informal employment has been most pronounced in the formal sector as contracting out of what were previously secure, regular, public, and private sector jobs has become common. This reflects a broader trend towards informalization in many OECD economies where neoliberal policy approaches to production and human resource management have seen an escalation in the contracting out of key business services. This is prevalent in both the private and public sectors. Employment in the service economy has been particularly vulnerable to the development of fixed-term and increasingly insecure forms of employment.

In developing countries, informal employment is a prevalent feature of the economy even when the agricultural sector is not counted. In most regions, informality defines more than half of non-agricultural employment: 82 percent in South Asia, 66 percent in sub-Saharan Africa, 65 percent in East and South East Asia, and 51 percent in Latin America. In the Middle East and North Africa, informal employment makes up 45 percent of non-agricultural employment, while Eastern Europe and Central Asia have a low level of informality at only 10 percent reflecting a history of central planning. In China, 33 percent of non-agricultural employment is informal (Vanek et al. 2014: 8).

Statistics on informal employment are commonly limited to the non-agricultural economy. However, it is important not to lose sight of agricultural employment when evaluating the reach of the informal economy. The vast majority of agricultural work is informally organized—either as self-employment or as casual/daily waged labor—with no basic social security or labor protection measures available to workers. Temporary labor migrants employed informally in another country are also not normally included in informal labor statistics. The informal nature of much of temporary labor migration is particularly pronounced in the case of female domestic workers who work in countries where the employment conditions of domestic workers are informal, and regulation and social security is absent (ILO 2013b: 41–45).

The mapping and measurement of informal employment in OECD economies is only just beginning. It is complicated by different models of the welfare state in which some countries provide universal health and social protection benefits to all citizens, and others deliver social protection as a workplace entitlement, but only for those engaged in standard employment relationships. This has made identifying a set of employment categories that reflect the ICLS’s 2003 conceptual framework difficult. In the most recent data, the categories of non-standard employment, atypical jobs, temporary, and part-time work are considered proxies for informality because they tend to deliver low employment security and limited access to social protection entitlements. These forms of non-standard or informal work are becoming a regular feature in OECD economies (ILO 2013a).

The associated rise in labor insecurity or ‘precarious labor’ is an idea increasingly cited in the literature on changing employment in post-industrial economies. Guy Standing (2011) argues the conditions of ‘precarity’ are a structural feature of global capitalism in the early twenty-first century, and that the neoliberal turn in many OECD economies is producing a new social class of workers denied the social and economic benefits gained by organized labor during the twentieth century. In this, and other literature on the changing nature of work, the focus is on the political economy of growing informalization. Emergent forms of informal employment in rich countries may not directly mirror those in low- and middle-income countries, but they do share many features in common and are producing a new class of working poor (Shipler 2004; ILO 2013a).

In addition to the large number of jobs provided by the informal economy, informal economic activities also make an important contribution to national and global GDP. Calculating the value of informal work and production is complex and the available data is not as complete as that for employment, but recent estimates of the contribution of the informal economy to GDP are high. If agriculture is included in the calculation, then informal economic activities account for nearly two-thirds of GDP in sub-Saharan Africa, 54 percent in India, and nearly one-third of Latin America’s GDP. When agricultural activities are excluded, then informal economic activities contribute half of GDP in sub-Saharan Africa, 46 percent in India, and one-quarter of Latin America GDP (Charmes 2012: 128). Estimates are not available for OECD economies but given the rapid expansion of informal employment in many of these countries, it is expected that the economic value produced by these workers is also growing.

Why does the informal economy persist even as economic growth, improved education, and health have come to many developing countries? Why is it an emerging feature of developed economies? And why is informality a ‘problem’?

The persistent reproduction and expansion of the informal economy in many countries can be understood as a function of its capacity to meet both the needs of the low-skilled masses for employment and the interests of global capital for cheap labor. That is to say, the informal economy has a dual function. The mismatch between growth in the working age population and the number of formal employment opportunities in many developing economies leaves the unskilled masses with no option except to create their own employment opportunities as wage laborers or in self-employment. Much informal employment is a survival strategy, a form of employment of last resort.

At the same time as the need for employment pushes people into informal forms of work, there is also a pull factor operating in these markets. Capital, both local and global, is attracted by a large pool of low-wage and unregulated labor that can be easily integrated into local and global production. Many of these workers operate essentially as industrial outworkers, often in their homes across Asia, Africa, and Latin America doing piece-rate work for global sporting, electronics, or garment companies. Periodically, reports of unrestrained exploitation, devastation, or death in informal workplaces become global news (Doherty 2012). Nevertheless, global value chains remain an important feature of global production and trade. The relationship between trade and employment is complex with empirical research showing that trade does produce new employment opportunities for the unskilled, but many of these, at least in the short-term, tend to be informal and marked by associated forms of socio-economic insecurity and vulnerability (Carr & Chen 2002; Bacchetta et al. 2009).3

Informal employment is closely linked to economic insecurity, poverty, and inequality. While not everyone who is informally employed is poor, there is a strong correlation between poverty and participation in informal employment. This is due to the exploitative nature of the social relations that structure informal employment, production, and exchange (Hill 2010). In contrast to ‘normal’ capital-labor relations, informal labor is incompletely separated from the means of production and subject to a range of non-capitalist methods of surplus production and accumulation. In the informal economy, exploitation is enhanced by the absence of formal employment contracts that normally offer some protection. Instead, labor control is maintained via a complex web of social and cultural relationships that are superimposed on unregulated labor market structures and operate beyond the purview of the state.

The insecurities and vulnerabilities associated with informal employment are therefore derived from both the worker’s employment status, and the location of their work. Informal workers are located in all forms of industry including agriculture, retail, manufacturing, and a myriad of services. Within this complex array of economic activities, the economic insecurity and vulnerability that defines informal employment are closely linked to a worker’s status as self-employed, as wage labor, or a dependent contractor (Carre 2013). The following four categories capture the various employment modalities that structure the informal economy and mediate a worker’s relationship with formal institutional and regulatory systems.

The self-employed. This category includes employers, own-account workers, and unpaid contributing family workers. The self-employed are not formally employed by another person, and work ostensibly on their own behalf in either their own small enterprise or as an independent contractor in a longer production chain. Employment as an independent contractor or ‘micro-entrepreneur’ is often presented as an autonomous form of economic activity in which the worker maintains a level of control over the working day. However, as sole traders responsible for the entire production and distribution process, many self-employed workers enter into permanent relationships with contractors and retailers in an attempt to secure continuous flows of employment. Social relations of gender, class, ethnicity, and class shape these informal relationships, allowing contactors to set the terms of production and exchange in their own favor. Difficulties in procuring official licenses that allow the self-employed to trade freely in a secure and regular environment also hamper productivity and economic security. In the absence of appropriate documentation, workers remain vulnerable to harassment and exploitation by local authorities in the form of bribery or the confiscation of goods. These structural forms of economic insecurity and exploitation are intensified by a lack of access to social security provisions such as paid sick leave, unemployment benefits, life insurance, and paid parental leave.

Wage employment. This includes casual day laborers, and short-term piece-rate and contract workers. Wage laborers may be employed on a regular basis but without a contract of employment. Casual workers rely on labor contractors or individual employers for the provision of work and can be employed on a monthly wage, a fixed daily rate, or on a piece-rate where they are paid according to the number of times a specific task is completed. Informal wage employment is typically insecure, subject to seasonal variations, and transient. Without an official employment contract workers are not protected by national labor laws and have no workplace entitlement to social security. With no formal employment contract, workers are vulnerable to the nonpayment and under-payment of wages.

Dependent contractors. This category includes industrial outworkers. Dependent contractors are formally dependent workers who enter into a direct relationship with either the factory from where the worker collects the raw materials ready for processing, or with a sub-contractor who delivers the raw materials to the worker’s home. These workers are paid on a piece-rate basis, with the total wage determined by the employer/contractor after production has been completed. The contractor or factory representative assesses the quality of the product, and sets the wage. Products deemed to be of poor quality or spoiled are deducted from the total wage, even when the quality of the finished product is directly related to the low quality of the original raw materials supplied. Gender, class, ethnic, and caste hierarchies are deployed to maximize the subordination and exploitation of dependent contractors.

The spatial relations of informal production. Where informal workers perform their work has a substantial impact on the social relations of informal production and the reward for work. Many informal workers—self-employed, dependent contractors, and domestic and personal service workers—are located in private homes, either their own, or that of their employer. The private nature of the home-based setting contributes to the potential for exploitative work conditions, and constrains worker socio-economic security. Home-based workers are particularly vulnerable due to their social isolation and the lack of protective labor laws. The individualized work experience of home-based employment makes it very easy for contractors and employers to use personal threats and misinformation to exploit workers, as well as to keep wages at a minimum and the hours of work long. In most countries, industrial laws do not regulate work undertaken in the private space of one’s own home or that of an employer, leaving workers with no protective regulatory framework.

Informal work performed in public spaces is also problematic. Vendors, waste collectors, construction, and transport workers perform their jobs on the streets where they compete for physical space and legitimacy with formal economy enterprises, private cars, and citizens. Informal workers trading in public are often harassed by authorities and abused by members of the public for using communal spaces to trade, even as they provide many of the essential services of the city. Lack of essential infrastructure, such as secure market places, shelter, drinking water, and public amenities adds to worker vulnerability curbing productivity and income earned.

The social and spatial relations of the different structures of informal employment mean that the socio-economic security and well-being of workers is largely determined by their employment status. This produces a stratified effect on the relationship between informal employment and the risk of poverty, with marked differences in outcome for employers, ‘regular’ wage earners, own-account operators, casual wage-workers, home-based and industrial workers, and those engaged in unpaid family work (see Figure 20.1).

Figure 20.1 WIEGO model of informal employment: hierarchy of earnings and poverty risk by employment status and sex Source: Chen (2012: 9).

Employers engaging in the informal economy tend to receive the highest average earnings and be least prone to the risk of poverty because they are least exposed to productivity and income-limiting dynamics in their daily work lives. Regular wage earners employed informally are not as protected and are exposed to a range of exploitative practices that constrain their earnings and put them at some risk of poverty. Own-account operators and or casual/daily wageworkers are much more vulnerable, as they face systemic forms of exploitation as discussed above. But variation in the relations of exploitation associated with different employment relationships causes the wages of regular wage earners to be higher than those of own-account workers who are more highly exposed to the risk of poverty.

The workers most vulnerable to exploitative and productivity-limiting practices are industrial outworkers and other ‘self-employed’ home-based workers. Vulnerability is reflected (and reproduced) in the low wages they receive and the associated risk of poverty. For all informal workers, limited access to protective labor laws and social security entitlements means that misadventure or natural disaster has a compounding negative impact on socio-economic security and wellbeing, leaving many informal workers vulnerable to chronic poverty. The link between informal employment and poverty has been observed in India: for example, informal workers are twice as likely (20.5 percent) as formal workers (11.3 percent) to be poor (NCEUS 2007: 24).

Gender is another stratifying feature of informal employment and its economic returns. In Latin America, sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia, and China, informal employment is a greater source of non-agricultural work for women compared to men (Vanek et al. 2014: 8).4 Moreover, within the informal economy, women tend to be disproportionately concentrated in the less secure, lower-paid types of employment as informal wage-workers, casual, and home-based workers. Men dominate the relatively more secure higher-waged forms of informal employment.

This is not only the result of direct discrimination, but also a reflection of the prevailing sexual division of labor (UN Women 2015). Across both developing and developed economies, women are assumed to be the primary carers of dependent family members and primarily responsible for the labor of social reproduction. This limits their capacity to perform paid work and a lack of supportive social infrastructure such as childcare and aged care services mean that the majority of women have limited choices about the type of paid work they do. In most cases, women seek employment that enables them to combine caring and household reproduction with paid work. This inevitably limits women’s productivity and hence economic security.

These structures of gender inequality are reflected in the very high rates of self-employed women in the informal economy, and their concentration in home-based forms of work— both of which severely limit productivity and wage-earning capacity. In all developing regions, self-employment constitutes a greater share of informal employment (non-agriculture) than wage employment, representing nearly one-third of total non-agricultural employment worldwide (ILO 2013a). Furthermore, women in all regions (except Eastern Europe and Central Asia) are more likely than men to be self-employed (ILO 2013a). Gendered hierarchies mean women are doubly exposed to the risk of poverty: they are more likely than men to be employed in the informal economy which typically delivers lower rates of pay than formal employment; and, women’s employment status locates them disproportionately towards the bottom of the informal labor market pyramid performing work that is highly vulnerable to exploitation, low wages, and poverty. This makes the informal economy and employment a key domain for researchers and policy advocates interested in women’s poverty, gender equity, and empowerment.

Since the 1990s, scholarship on the informal economy has burgeoned. Most of the research has been focused on improving data collection and policy initiatives. National labor force survey tools have been developed to improve the enumeration of the size and value of the informal economy, and informality has become a regular feature of policy debates on economic development and women’s workforce participation in developing countries in particular. An international consensus—at least in policy circles—on what defines ‘informality’ has also been settled, with a focus on the relationship between employment and social security.

Informal workers have established their own membership-based organizations and lobbied for new forms of social security and workplace rights. Street vendors around the world advocate for their interests through global organizations such as StreetNet International. Home-based workers organize through HomeNet South East Asia and HomeNet South Asia. Domestic workers have organized the first global union run by women—the International Domestic Workers’ Federation (IDWF). These and other national, regional, and local level informal worker organizations have successfully joined with other policy advocacy forums to secure, among other things, two international labor conventions directly aimed at improving employment and livelihoods of some informal workers: the ILO Convention on Home Work No. 177 (1996) and the ILO Domestic Workers Convention No. 189 (2011). Both conventions provide guidelines for countries to recognize, protect, and regulate informal workers.

These statistical, conceptual, organizational, and regulatory initiatives are supported by an international consensus that economic growth must be inclusive and that such inclusivity relies fundamentally on the availability of decent employment. The most recent articulation of this view is the UN Sustainable Development Goal 8, which aims to ‘promote inclusive and sustainable economic growth, employment and decent work for all’ (SDG 8).5 This follows up the ILO’s 2013 declaration that formalizing the informal economy is one of the Organization’s eight areas of critical importance.

The International Labour Conference’s ‘Recommendation 204’ sets out a coherent agenda for global action promoting transition from the informal to the formal economy along three pathways: the transition of workers and economic units from the informal to the formal economy; the creation of enterprises and decent jobs in the formal economy; and, preventing the informalization of formal jobs (ILC 2015). The Recommendation provides guidelines on mainstreaming economic formalization through appropriate legal and policy frameworks, employment policies, rights and social protection, good governance, social dialogue, and worker organization.

The Recommendation highlights the need for a policy framework that promotes informal worker access to the formal conditions of employment, including social security, maternity protection, decent working conditions, minimum wage, and affordable quality childcare. For small informal enterprises, the focus is on policies that reduce the barriers to and costs of formal registration and compliance, and that improve access to credit and insurance products and business training and skill development programs. Guidelines for improving industrial relations are also included and emphasize freedom of association and collective bargaining. It is important to note that Recommendation 204 is not directed solely at developing economies. The policy measures directly challenge the shift towards contracting-out, casualization, and other forms of precarious informal models of employment that have become so pervasive in OECD economies.

In many respects, the UN’s SDG 8 and the ILC’s Recommendation 204 call for the maintenance and extension of the post-World War II industrial relations compact that underwrote widespread prosperity and well-being in the industrialized countries. Achieving this type of policy shift will be a complex and difficult task, both practically and politically. Policy advocates argue that formalization needs to be understood as “a gradual, ongoing process of incrementally incorporating informal workers and economic units into the formal economy through strengthening them and extending their rights, protection and benefits” (WIEGO 2014). What is not discussed is the controversial nature of the formalization/decent work agenda. Formalization of the informal economy would support inclusive growth, but it would also threaten current global dynamics of capitalist development and accumulation in which the informal economy is a fundamental but subordinate feature. It is not certain if global capital would stand by while the conditions of informality that currently underwrite global competition and capital accumulation are challenged.

The formalization agenda is also likely to be politically difficult. Policies to formalize the informal economy through increased regulation and social security provision challenge the prevailing neoliberal culture of governance in both rich and poor countries, including ideas of small government, free markets, and limited social spending. The contradiction between the demands of the international policy agenda and the logic of global structures of capital accumulation and governance suggests that transformation in the socio-economic security and well-being of informal workers will not be a simple matter of technical or administrative change. Instead, access to decent formal employment will require worker organization and struggle beyond what has already been achieved through global labor conventions, national bills for social security, and provincial level agreements for improved wages and conditions for informal workers. The informal workforce is vast and continues to grow. Perhaps contemporary concerns about the negative relationship between inequality and economic growth will provoke increased impetus for global change.

1 The language used to describe ‘informality’ in the economy varies across the literature and includes the informal sector, the informal economy, informal enterprises, economic informality, and informal employment. In the statistical literature the terminology used has very specific meanings. In much of the general literature these terms are often used interchangeably and refer to economic activities and processes that are not bound by formal regulations of the state.

2 Informal sector enterprises were characterized by ease of entry into the market; a reliance on indigenous resources; family ownership of the enterprise; small scale of operation; dominance of labor-intensive production processes by workers who acquired their skills outside of formal training institutions; and operation in unregulated and competitive markets. Formal sector enterprises were characterized by difficulty of entry into the market; their reliance on foreign resources; corporate ownership; large-scale operations in regulated markets protected by tariffs, quotas’ and trade licenses; and the use of capital-intensive and imported technology by workers who were formally trained (ILO 1972).

3 A recent analysis of the literature on the relationship between trade openness and economic informality concludes that while in most cases “trade reforms increase the incidence of informal employment, . . . [the] impact on informal sector wages is ambiguous and depends on circumstances and country specificities” (Bacchetta et al. 2009: 67).

4 This varies across regions but is most marked in sub-Saharan Africa where 74 percent of women nonagricultural workers are informally employed compared to 61 percent of men; and in Latin America where 54 percent of women non-agricultural workers are informally employed in comparison to 48 percent of men.

5 http://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-development-goals/

Bacchetta, M., Ernst, E., & Bustamante, J.P. 2009. Globalization and informal jobs in developing countries . Geneva: ILO-WTO co-publication. Available from https://www.wto.org/English/res_e/booksp_e/jobs_devel_countries_e.pdf [Accessed August 21, 2015]

Beneria, L. 2003. Gender, Development, and Globalization: Economics As If All People Mattered. New York: Routledge.

Breman, J. 1976. ‘A dualistic labour system? A critique of the ‘informal sector’ concept.’ Economic & Political Weekly, 11: 1870–1876, 1905–1908, 1939–1944.

Carr, M. & Chen, M.A. 2002. Globalization and the informal economy: how global trade and investment impact on the working poor. Working Paper on the Informal Economy 2002/1. Geneva: International Labour Office.

Carre, F. 2013. Defining and categorizing organizations of informal workers in developing and developed countries . WIEGO Organizing Brief No. 8, September. Cambridge, MA: WIEGO.

Charmes, J. 2012. ‘The informal economy worldwide: trends and characteristics.’ Margin: The Journal of Applied Economic Research, 6 (2):103–132.

Chen, M. 2006. ‘Rethinking the informal economy: linkages with the formal sector and the formal regulatory environment,’ in: B. Guha-Khasnobis, R. Kanbur, & E. Ostrom (eds.), Linking the Formal and Informal Economy: Concepts and Policies. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 77–92.

Chen, M. 2012. The informal economy: definitions, theories and policies. WIEGO Working Paper No. 1 . Cambridge, MA: WIEGO. Available from http://wiego.org/sites/wiego.org/files/publications/files/Chen_WIEGO_WP1.pdf [Accessed February 18, 2016]

Daly, H.E. & Cobb, J.B. 1989. For the Common Good: Redirecting the Economy Toward Community, the Environment, and a Sustainable Future. Boston: Beacon Press.

Davies, R. 1979. ‘Informal sector or subordinate mode of production? A model,’ in: R. Bromley & C. Gerry (eds.), Casual Work and Poverty in Third World Cities. New York: John Wiley & Sons, 87–104.

De Soto, H. 1989. The Other Path: The Invisible Revolution in the Third World. London: I.B. Tauris.

De Soto, H. 2000. The Mystery of Capital: Why Capitalism Triumphs in the West and Fails Everywhere Else. New York: Basic Books.

Doherty, B. 2012. ‘Poor children made to stitch sports balls in sweatshops.’ Sydney Morning Herald, September 22.

Gerry, C. 1978. ‘Petty production and capitalist production in Dakar: the crisis of the self employed.’ World Development, 6 (9–10): 1147–1160.

Frank, A.G. 1967. Capitalism and Underdevelopment in Latin America. New York: Monthly Review Press.

Frank, A.G. 1975. On Capitalist Underdevelopment. Bombay: Oxford University Press.

Harris, J.R. & Todaro, M. 1970 ‘Migration, unemployment and development: a two sector analysis.’ American Economic Review, 60 (1): 126–142.

Hart, K. 1973. ‘Informal income opportunities and urban employment in Ghana.’ The Journal of Modern African Studies, 11 (1): 61–89.

Hill, E. 2010. Worker Identity, Agency and Economic Development: Women’s Empowerment in the Indian Informal Economy. London: Routledge.

Horn, Z. 2009. No cushion to fall back on: the global economic crisis and informal workers. WIEGO Inclusive Cities Study . Available from http://wiego.org/sites/wiego.org/files/publications/files/Horn_GEC_Study_2009.pdf [Accessed August 20, 2015]

International Labour Conference (ILC). 2015. Recommendation 204 concerning the transition from the informal economy, adopted by the Conference at its one hundred and fourth session, Geneva, 12 June. Available from http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—ed_norm/—relconf/documents/meetingdocument/wcms_377774.pdf [Accessed August 21, 2015]

International Labour Organisation (ILO). 1972. Employment, Incomes and Equality: A Strategy for Increasing Productive Employment in Kenya. Geneva: International Labour Office.

International Labour Organisation. 1993. Report of the Conference. The XVth International Conference of Labour Statisticians. January 19–28, Geneva: International Labour Office.

International Labour Organisation. 2002. Decent Work and the Informal Economy: Report VI. International Labour Conference, 90th Session. Geneva: International Labour Office.

International Labour Organisation. 2003. Report 1: General Report. Seventeenth Conference of Labour Statisticians. November 24–December 3. Geneva: International Labour Office.

International Labour Organisation. 2013a. Women and Men in the Informal Economy: A Statistical Picture, 2nd edn. Geneva: International Labour Office

International Labour Organisation. 2013b. Domestic Workers Across the World: Global and Regional Statistics and the Extent of Legal Protection. Geneva: International Labour Office.

Jutting, J.P. & de Laiglesia, J.R. (eds.) 2009. Is Informal Normal? Towards More and Better Jobs in Developing Countries. Paris: OECD.

King, K. 1974. ‘Kenya’s informal machine makers: a study of small scale industry in Kenya’s emergent artisan society.’ World Development, 2 (4–5): 9–28.

LeBrun, O & Gerry, C. 1975. ‘Petty producers and capitalism.’ Review of African Political Economy, 2 (3): 20–32.

Leonard, M. 1998. Invisible Work, Invisible Workers: The Informal Economy in Europe and the US. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Lewis, A.W 1954. ‘Economic development with unlimited Supplies of labor.’ The Manchester School, 22 (2): 139–191.

Leys, C. 1973. ‘Interpreting African development: reflections on the ILO report on employment, incomes, and inequality in Kenya.’ African Affairs, 72 (289): 419–429.

Meagher, K. 2013. Unlocking the informal economy: a literature review on linkages between formal and informal economies in developing countries. WIEGO Working Paper 27, Cambridge, MA: WIEGO.

Mies, M. 1986. Patriarchy and Accumulation on a World Scale: Women in the International Division of Labour. London. Zed Books.

Moser, C. 1978. ‘Informal sector or petty commodity production: dualism or dependence in urban development?’ World Development, 6 (9/10): 1041–1064.

National Commission for Enterprises in the Unorganized Sector (NCEUS). 2007. Report on Conditions of Work and Promotion of Livelihoods in the Unorganized Sector. New Delhi: Government of India.

Obregon, A. 1974. ‘The marginal pole of the economy and the marginalised labour force.’ Economy & Society, 3 (4): 393–428.

Portes, A., Castells, M., & Benton, L. (eds.) 1989. The Informal Economy. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Santos, M. 1979. The Shared Space: Two Circuits of the Urban Economy in Underdeveloped Countries. London: Methuen.

Shipler, D.K. 2004. The Working Poor: Invisible in America. New York: Vintage.

Standing, G. 1999. Global Labour Flexibility: Seeking Distributive Justice. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Standing, G. 2011. The Precariat: The New Dangerous Class. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

UN Women. 2015. Progress of the World’s Women 2015–2016: Transforming Economies, Realising Rights. Available from http://progress.unwomen.org/en/2015/pdf/UNW_progressreport.pdf [Accessed August 20, 2015]

Vanek, J., Chen, M.A., Carre, F., Heintz, J., & Hussmanns, R. 2014. Statistics on the informal economy: definitions, regional estimates & challenges. WIEGO Working Paper (Statistics) No. 2, April. Cambridge, MA: WIEGO.

Wallerstein, I. 1974. The Modern World System I: Capitalist Agriculture and the Origins of the European World-Economy in the Sixteenth Century. New York: Academic Press.

Waring, M. 1988. Counting for Nothing: What Men Value and What Women are Worth. North Sydney: Allen & Unwin.

WIEGO. 2014. WIEGO Network Platform: transitioning from the informal to the formal economy in the interests of workers in the informal economy. Available from http://wiego.org/sites/wiego.org/files/resources/files/WIEGO-Platform-ILO-2014.pdf [Accessed on August 15, 2015]