Figure 21.1 The process of human development

Marcella Corsi and Giulio Guarini

It will be seen how in place of the wealth and poverty of political economy come the rich human being and rich human need. The rich human being is simultaneously the human being in need of totality of human life—activities—the man in whom his own realization exists as an inner necessity, as need.

Karl Marx, The Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844

A unanimously agreed idea of what heterodox economics is and where its borders are does not exist. So far, after decades of debate, opinions remain divided on the subject (Lee 2012; Elsner 2013). Thus, in dealing with inequality and poverty, we define here heterodox economics on the basis of the relationship with classical economics, on the one hand, and the attention to ‘diversity,’ on the other. Generally, the contemporary mainstream economic literature assumes that economic behavior can be explained through the same process applying to all individuals, at most exhibiting quantitative differences in the extent of certain individual properties (the approach of heterogeneity). Some heterodox approaches, as well as other social science disciplines, assume instead that individuals can be grouped into aggregates for the sake of analysis, and each group is subject to its own laws of behavior, fundamentally influenced by the socio-economic environment: the approach of diversity (D’Ippoliti 2011). By drawing on the classical economists, an approach based on the concept of diversity, we base our discussion on the consideration that individuals are characterized by different income levels, and are subject, some more than others, to the risks of social exclusion and poverty.

Social exclusion affects the most vulnerable individuals more severely, creating treacherous social traps; the effects of which can only be mitigated through social institutions. This implies a potential capacity for social innovation on the part of public institutions, in initiating inclusive actions adapted to address the persistent problems of social reality.

This chapter consists of two main sections. In the first section, we consider income inequality, with particular reference to the stochastic approach to the distribution of personal income. Then, in the second section, we discuss social exclusion, focusing on some theoretical and empirical dimensions of poverty, namely in the labor market, financial market, and the education system.

In this broad framework, we mostly refer to the contributions made by classical economists and by Amartya Sen, the founder of the capability and human development approach. We integrate these contributions with specific complementary perspectives, such as that of feminist economics. The main thread linking this discussion is an objective to achieve social justice within the capitalistic economic system. According to the classical viewpoint, economics is a social science, intrinsically interconnected with social, cultural, and political contexts (Martins 2011, 2012). Inequality and social exclusion represent two of the main economic aspects that can negatively influence economic and civil development. On the one hand, for a given level of poverty, a significant worsening of income distribution can generate social insecurity and political instability. On the other hand, for a given level of income distribution, an increase in poverty makes the economic system unable to ensure basic social conditions in terms of health and education. For this reason, the classical economists, although from different theoretical and political positions, evaluate inequality and poverty as two separate and distinct topics, but belonging to the same framework of economic development.

The nature, causes, and consequences of economic inequality have been widely investigated by economists; the first notable analysis of these topics was by Adam Smith. In The Wealth of Nations, Smith states that personal income distribution is affected by the institutional aspects of society but is independent of the economy; in this sense, as a result of economic growth, individual incomes move upwards rather proportionally (Smith [1776] 1976: 80, 159). In contrast, in the Principles of Political Economy, John Stuart Mill (1848: 699) addresses a concern that economic progress could change the income shares accrued to the middle classes, without improving the economic condition of the poorest sections of the population. However, it is with David Ricardo, and later with Karl Marx, that the distribution of income becomes a central theme of classical political economy, focusing on the social antagonisms within the process of distribution of the surplus in society and among its classes.

Income distribution remains important in Jean-Baptiste Say’s work who explicitly considers personal income distribution as an indispensable element of the analysis of the demand for a good. According to Say, if a product price decreases in relation to individual incomes, more and more consumers will demand it, while less and less will demand it as it becomes more expensive (Say 1836: 272–273).

The same approach characterizes the work of Vilfredo Pareto, who for the first time describes the shape of the income curve as the basis of his analysis of aggregate demand (Pareto [1897] 1964). Even if different from the original Paretian one, the hypothesis that the frequency distribution of earners could be considered a stable relationship, and of general validity, subsequently stimulated a large number of analyses aimed at providing an adequate description of the phenomenon and/or at identifying its determining variables.

The degree of inequality in the distribution of personal incomes can be considered the result of a conflict between two sets of forces:

The forces of diversification: (i) institutional and social norms that tend to favor wealthy people and their heirs, guaranteeing a monopoly of certain occupations and certain properties; and, (ii) the impossibility of acquiring those qualifications that give access to certain income levels (age, race, gender, etc.).

The forces of assimilation: (i) progressive taxes, (ii) inheritance taxes, and (iii) social services, which together provide those on the lowest income with better opportunities to increase their standard of living and limit the tendency of the rich and their heirs to become richer (Champernowne l973: 190).

There are some forces of change that modulate the distribution of income to make it converge towards equilibrium; however, “for the presence of pulses to change (which act for a short period of time) and for the gradual modification of the same forces of change, such an equilibrium distribution is never reached” (Champernowne 1973: 9).

The Pareto approach, and more generally the stochastic approach to income distribution also discussed by Gibrat (1930) and Champernowne (1973), among others, has made a significant contribution to the understanding of income differentials with its analysis of the empirical laws of income distribution. All models have, as a common starting point, the observation of the existence of inequality seen as an asymmetry of income distribution, in which a large portion of total income goes to a small portion of the population. This empirical observation can be explained by assuming that every individual gets income by virtue of his or her own characteristics. The distribution of income depends on the distribution of the qualifications necessary to obtain such income: income differences between individuals in a community reflect their different qualifications. The characteristics normally taken into account are individual skills, personal wealth, and occupation, which are by assumption considered freely tradable between income earners. However, these characteristics must be complemented by other qualifications that are not sold but significantly affect the opportunities of an individual to receive a certain income level: age, sex, social status, race, and disability (defined as grounds for disadvantage or prejudice).

Moreover, it should be borne in mind that individual qualifications are not independent of the social structure of the community in question, as well as the contingent economic conditions. In particular, economic factors influence the distribution of income, which in turn influences access to qualifications and their relative value. Inertial phenomena (habits, conventions, and institutional factors) are at the basis of the strong dependence of the distribution of current income from that of the past. In these terms, income distribution is both malleable (could be different) and persistent. Economic structures as well as collective values recognized by society create such a lack of flexibility in income distribution (Sen 1992).

Within the heterodox literature on inequality, an original and important contribution focused on gender inequality is offered by feminist economics. According to Robeyns (2003), the feminist viewpoint introduces three relevant elements to the analysis of inequality. The first general point is that every economic issue is gender-conditioned. While mainstream economics considers inequality, and in particular the gender gap, to be an ‘accident’ in respect of the theoretical hypothesis of equilibrium and socio-economic harmony, the feminist view affirms that the economy is not gender neutral, and gender inequality can represent both the cause and the effect of most economic processes. Thus, an inequality analysis that does not take into account gender is not neutral, but de facto follows a masculine perspective and this creates false gender neutrality (Okin 1989).

Second, feminist studies explore the issue of inequality within the household. While mainstream works assume that the household represents a homogeneous and compact unit of analysis, feminists argue that a good level of household income can hide relevant economic discrimination among its members, especially women, which generates serious economic exclusion. Thus the mainstream assumption of an equal income distribution among household members is theoretically incorrect and politically pernicious.

Finally, feminist analyses take into account economic relations outside of formal market exchange. In fact, different forms of discrimination and inequality can be found in informal economic contexts. The investigation of activities, such as care work and household labor, enlarges the field of research, offering a new spectrum in which to consider gender inequalities.

Thus, the feminist view enriches the inequality debate not only by considering gender inequality, that is one of the pillars of social injustice, but also by introducing the aforementioned elements of analysis that are also useful to evaluate other kinds of inequality, such as intergenerational inequality or ethnic inequality within informal markets.

In the era of globalization, the international dimension of inequality is becoming more and more fundamental. According to Milanovic (2013), the increasing movement of people, financial capital, and technologies make the generation of individual income dependent on global dynamics. Furthermore, the perception and the satisfaction deriving from individual economic status are strongly influenced by the globalization of information and faster flows of persons and commodities. In the world of today where economic borders are becoming more and more opaque, inequality among individuals should be analyzed with an international approach that combines inter-state inequality with intra-state inequality. To this end, Milanovic (2013) indicates three kinds of inequality: the first considers inequality across nations, the second integrates the first one by measuring population sizes, while the third, called ‘global inequality,’ is individual-centered, and is calculated on the basis of individual income without accounting for nationality.

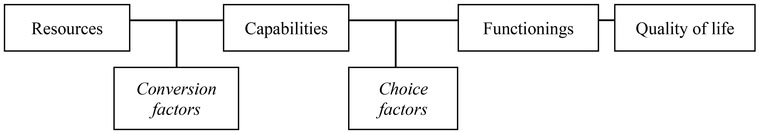

The human development approach is the main reference point for policy development at national and international levels. Human development, according to Amartya Sen, is the process of determining individual and collective well-being. It is a process in which each person turns the resources at his or her disposal to acquiring the constituent elements of well-being and quality of life. These elements, otherwise known as ‘states of being and doing,’ are called ‘functionings.’ The effective freedom to acquire functionings is a capability; the transformation of resources in capabilities depends on conversion factors that are both subjective and linked to the social, economic, and institutional context, as well as on choice factors that intervene in the passage of the set of capabilities to that of functionings. Figure 21.1 illustrates the aforementioned process of human development.

Each person participates in this process both as an individual and as a member of a community. Capabilities have an intrinsic value because the very fact of having the freedom to pursue all opportunities offered by the economic and social system is an element that improves the quality of life. They also have an instrumental value because they are the precondition for improving one’s quality of life. Each individual may acquire resources independently of his or her wellbeing, and this ability is called freedom of agency, that is the ability of the individuals “to promote their own well-being, but also to bring about changes in their community” (Sen 1999: 19). It may involve either resources related to the individual (weak agency) or resources that concern the welfare of others (strong agency) (Sen 1999).

Figure 21.1 The process of human development

The role of institutions is to provide the instrumental freedoms that fall in the conversion factors. According to Sen (1999), these are: political freedoms, such as direct and indirect participation in political life; economic infrastructure that allows for production, consumption, and the exchange of goods and services; social opportunities, understood as goods and services that help to improve the quality of life; guarantees of transparency concerning the rules of the game in the market but also in institutions; and, social security against the risks linked to poverty.

According to Robeyns (2003), this approach can be integrated into a feminist study of gender inequalities both by considering the human development process as a specific gender conversion factor, and/or by re-interpreting the human development process as gendered capabilities and functionings.

The concept of social exclusion is complex and difficult to define. The discourse on social exclusion offers operational definitions that highlight important aspects that facilitate its analysis. Sen does not formulate a precise definition of social exclusion, but outlines several of its characteristics. According to Sen (1999), poverty is capability deprivation, meaning the inability to live a minimally decent life, while social exclusion can be understood as the permanence of this condition. For example, we can define social exclusion as a permanent deprivation of those capabilities needed in order to be fully integrated in society.

For the definition of these capabilities, we can refer to some of their constituents. First of all, these capabilities involve the element of social justice, which implies,

[h]aving the social bases of self-respect and non-humiliation; being able to be treated as a dignified being whose worth is equal to that of others. This entails provisions of nondiscrimination on the basis of race, sex, sexual orientation, ethnicity, caste, religion, national origin.

Nussbaum 2003: 42

A second element is that of active participation that can be defined as the ability “to relate to others and to take part in the life of the community” (Sen 2000: 13). Finally, social exclusion can be defined as the deprivation of social capabilities, that is,

to be integrated in networks; to commit oneself to a project within a group, aimed at serving a common good, a social interest; to take part in decision making in a political society; to have specific attachments to others (friendship, love); to try to value others’ objectives, considering them as ends.

Sen 2000: 13

Social exclusion affects both individual and collective agency, and in particular self-help, defined as “the ability of the people to help themselves and to influence the world” (Sen 2000: 13). Social exclusion can reduce agency and self-help through the reduction of “the critical consciousness of the poor to express their social discontent, think critically about their problems and actively resolve these problems” (Sen 1999: 18). This greatly reduces the quality of life of individuals because self-help interacts positively with instrumental freedoms. In fact, it allows individuals to be able to perform voice actions to promote their own needs; it is an economic facility because it can generate income by creating new social opportunities and reducing the imbalance of powers; it can improve transparency in the community bringing out trust and reciprocity; and, it can strengthen social protection.

Social capital, defined “as the set of social relations and networks enabling the poor to form and sustain self-help groups” (Ibrahim 2006: 409), can positively influence collective action in several ways: it spreads trust and reciprocity, helps in making collective decisions (regarding the objectives and the distribution of benefits), allows the dissemination of information and coordination of activities, and protects community members from possible economic shocks. Furthermore, it encourages participation in local decision-making processes and helps to ensure new individual and collective rights. Social capital may be the only real resource for vulnerable people, “because poor people (by definition) have little economic capital and face formidable obstacles in acquiring human capital (that is education), social capital is disproportionately important to their welfare"(Putnam 2000: 18).

The generators of the process of social exclusion are the so-called ‘drivers of exclusion,’ that is, the inputs that convert personal and context vulnerability into actual social exclusion. There are three different drivers of social exclusion: active exclusion, passive exclusion, and self-exclusion.

Active exclusion occurs due to discriminatory actions by powerful public or private groups concerning policy decisions that victims are not able to prevent or counteract. These power groups are socially and culturally identifiable. Passive exclusion occurs due to changes in the structure and organization of society and institutions. Specifically, there may be social, cultural, and economic changes that lead to such exclusion. Finally, self-exclusion occurs when individuals or groups self-marginalize due to their natural attitudes, behaviors, and values. They are thus responsible for their own exclusion.

Social exclusion involves complex processes in which drivers may be central or residual with respect to structural changes, or may depend on the ineffectiveness of policies (structural dislocation ). Furthermore, social exclusion may be regarded as an integral part of capitalist development: in this case, the policy will aim to transform the structural causes (structural dualism), rather than reabsorbing them. Finally, social exclusion can be seen as a result of the ineffectiveness of community policies due to the separation between economic and social policies, as well as due to the gap existing between community institutions and the needs of citizens, and the content of economic policies such as excessive flexibility of the labor market (institutional exclusion).

Globalization is a phenomenon that affects directly and indirectly both the drivers of social exclusion and vulnerability factors. It is therefore appropriate to analyze the relationship between social exclusion and globalization. Globalization may be defined as:

a process (or set of processes) which embodies a transformation in the spatial organisation of social relations and transactions – assessed in terms of their extensity, intensity, velocity and impact – generating transcontinental or interregional flows and networks of activity, interaction and the exercise of power.

Beall 2002: 43

From this definition, three typical effects of the globalization process emerge. First, there is a widening of social, economic, and political relationships beyond national borders. In addition, there is an intensification of the interconnection between financial, trade, and migration flows, due to the development of communication systems and transportation. Finally, the local impact of global events becomes more remarkable as the boundary between the global and the local level becomes more fluid.

Following McGrew (2000), we can identify some interpretations of the link between globalization and social exclusion. From the neoliberal view, what prevails is an optimistic view that general welfare is achieved, with the end of the so-called Third World, through the establishment of a single global market and a steady thinning of public interventions in the organization of the economic system. International institutions, such as the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank, and the World Trade Organization, are the only institutions that can facilitate the formation of a single global system, while nation states are entities with less and less powers and organizational capacities to regulate global phenomena. In this context, social exclusion is an unpleasant but inevitable side effect to the global economic process. In rich countries, the excluded belong to those who are directly affected by trade liberalization, with the ensuing reduction in privileges and social security.

From a radical view, globalization reinforces transnational capital resulting in global inequalities and marginalization of poor countries; the world is divided into smaller blocks, in which the OECD countries are the main leaders. In this context, attention to the new concept of social exclusion is a way to reduce economic inequality produced by the global mechanisms.

Finally, from the transformationalist view, globalization is seen as a period of major structural changes across the world, which witnesses the formation of new global systems, new hierarchies, and new mechanisms of inclusion and exclusion. From this perspective, it becomes essential to study the distribution of power between regions and groups in terms of methods, tools, distribution of income, and organization. Social exclusion is analyzed by studying social relations present in the formal and informal institutions and their changes with developments in international relations, their social impacts, and their reactions. Castells (1998) argues that “globalization proceeds selectively, including and excluding segments of economies and societies in and out of the networks of information, wealth and power that characterize the new dominant system” (Castells 1998: 161–162).

Another element that affects the process of social exclusion and the degree of vulnerability of individuals is social stratification. Social stratifications vary in different aspects: in the number of layers, in the difference between the first and the last layer, in the dimension of each layer, in the layer composition (in terms of gender, social, economic, cultural, ethnic characteristics), and in the degree of movement between the layers of the individuals. In this context, social mobility is defined as the passage of a proportion of individuals from a layer to another, in ascending or descending direction. It is intergenerational if the comparison is between parents and children; intragenerational, if the comparison is between two different periods with respect to the same individual. Social exclusion can thus be a form of downward social mobility or social immobility.

Poverty can be classified into two main categories: absolute and relative. Absolute poverty means that people lack a minimum amount of income that satisfies basic needs for survival. Relative poverty refers to a condition of people not receiving enough income to maintain an average standard of living measured for a particular society and time. A measure of relative poverty can be converted into a measure of inequality and of social exclusion.

The transition from the concept of poverty to that of social exclusion involves the passage from a one-dimensional to a multi-dimensional vision, from a pre-eminence of social elements over economic ones to an interest in the quality of social relations. Social exclusion is not an alternative concept of poverty, but it is a way to clarify its understanding. According to Jackson (1999), social exclusion and poverty are interrelated, albeit distinct, concepts: poverty often results from social exclusion. According to Atkinson (1998), social exclusion is due to poverty and/or inequality. Some people may be excluded without being poor while others, although poor, may not be excluded (especially in depressed areas, where they can live under a minimum threshold, but still participate in social life).

There is a strong interaction between social exclusion and poverty. And there may be a cumulative vicious circle whereby poverty and social exclusion feed each other. The transition from poverty as deprivation of means to poverty as deprivation of capabilities involves shifting attention from the lack of means to their inadequacy in respect to capabilities and to the conversion of means into substantial freedoms.

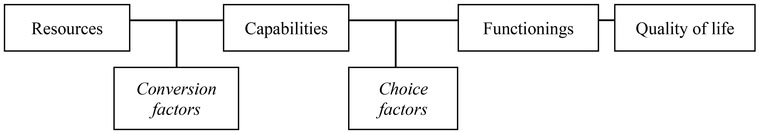

The prevalence of unemployment, especially long-term unemployment, is perhaps the single most important contributor to the persistence of social exclusion on a large scale. According to Sen (1996), we can consider three aspects of the link between unemployment and social exclusion: income aspects, recognition aspects, and production aspects.

As to income aspects, unemployment is directly linked to economic deprivation. Sen (1997) argues that it is inappropriate to affirm that non-participation in the labor market is not a major problem because there is a welfare system that can guarantee social benefits and a minimum income. In fact, this approach is not sustainable in the long-run, since being out of the labor market has a fiscal cost for society. Moreover, the exclusion from the labor market can be a real deprivation of capabilities, making the individual unable to participate in economic life.

As to recognition aspects, unemployment can cause severe psychological damages: some empirical studies emphasize the positive correlation between suicide rates and conditions of permanent unemployment (see Boor 1980; Platt 1984). Moreover, there may be related health effects, with a subsequent negative impact on social relations: there is a loss of social relations, starting within the family.

Finally, concerning production aspects, there is a negative effect on education. On the one hand, there is a loss of learning, since we learn by doing, and we therefore unlearn by not doing. On the other hand, there is a decline in cognitive ability caused by mistrust and resignation. When it becomes difficult to be employed, competition between workers emerges, directly affecting those most vulnerable. Long-term unemployment may cause the individual to develop negative feelings against the society that does not include them, leading, in some cases, to the risk of illegal activity. Figure 21.2 illustrates the relationship between the aforementioned concepts.

Figure 21.2 The relationship between unemployment and social exclusion

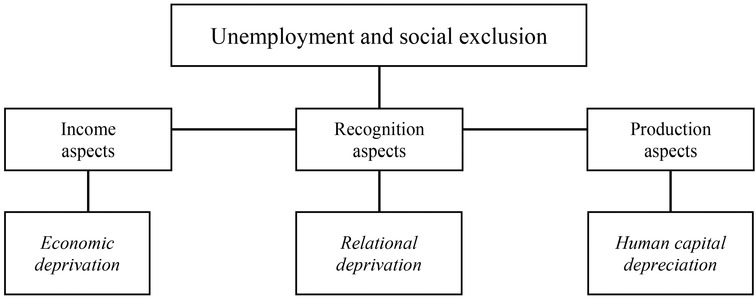

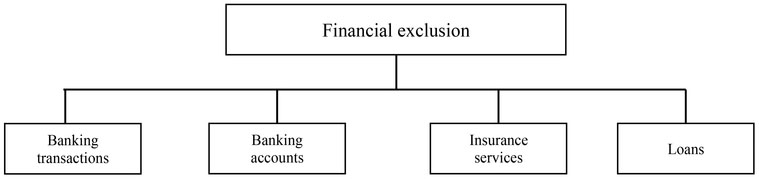

Financial exclusion can be defined as “a process whereby people encounter difficulties accessing and/or using financial services and products in the mainstream market that are appropriate to their needs and enable them to lead a normal social life in the society in which they belong” (European Commission 2008: 9).

It is in fact difficult to estimate those who are excluded from the financial system and in particular those who have no access to credit because exclusion can have different temporal (temporary and permanent) dynamics, and because the supply of financial services is typically very complex. There are different types of financial services, the exclusion from which can be indicative for our analysis (see Figure 21.3). For example, exclusion from banking transactions, such as receiving regular payments (salaries, pensions, public subsidies), the ability to cash checks, to pay utilities electronically, to pay goods without cash, and to send remittances (in the case of migrants). Such financial exclusion, being inherent in the basic economic activities of a developed society, causes economic and social marginalization. Moreover, it implies the exclusion from all other financial services and it reduces security in the management of money.

Another form of financial exclusion is an inability to access a bank account due to a low income and a lack of proper identification documents in the case of immigrants. The ‘unbanked’ are those individuals who do not have an account in a bank. In the case of businesses, the same problem is manifested in a lack of access to credit. This results in the exclusion from credit, such as loans, from the possession of a credit card, and from overdraft banking. This exclusion often leads ‘unbanked’ individuals (and businesses) to rely on risky informal and illegal channels as a source of funds.

Finally, there is the exclusion from insurance services. It is important to consider this exclusion with regard to poverty because private insurance services are increasingly replacing social welfare benefits. Therefore, such exclusion creates the risk of failing to meet a minimum standard of living.

The causes of financial exclusion can be both exogenous and endogenous. For individuals, exogenous causes are employment instability, poor health, low levels of education, and gender or migrant status. For example, families are in a vulnerable position when they are not owners of their home, when they live in a marginal geographical area with dependent people such as children and elderly people, and when they are single-parent (especially single-mother) families. Finally, exogenous causes of financial exclusion for companies can be: their small size, the economic vulnerability of the owner, the local character of the goods or services sold, an inadequate infrastructural context.

Figure 21.3 The dimension of financial exclusion

Below we analyze the main causes of financial exclusion that are endogenous to the financial market. The first is credit rationing due to the phenomenon of ‘enforcement’: the higher the cost of compliance with the contract terms for reasons related to the national legal system or to local regulations, the greater the tendency of the creditor to avoid low-income individuals, who require very small financing and mostly reside in areas where the cost is higher (for formal and informal rules). Another factor of credit rationing is the costs of transaction, that is, the costs associated with contract preparation, access to information, trading, and the monitoring of compliance with the contract. Obviously, with the same transaction costs, individuals requesting a small amount of credit do not generate a profitable lending. Another endogenous element of financial exclusion is the inadequate geographical distribution of creditors: the lower the spread, the more difficult is the adaptation of credit offers to customer requests, especially for the most marginalized clients. Another element is the cost of the loan, the price, and other conditions of lending (such as evaluation time, documentation, amount and duration of the loan, repayment frequency, possibility of re-negotiation), which can make a loan too onerous and then make access to credit impossible for vulnerable people or businesses.

Financial crime and the associated social problems have a negative impact on the banking sector too, which can in turn induce further credit rationing. The negative effects of crime on banks are twofold: an increase in the cost of trading and an increasing difficulty for banks to assess the financial conditions of their customers due to asymmetric information. As a result, credit rationing in many crime-affected areas becomes a characteristic phenomenon of the banking system. A high level of crime involves higher interest rates, but does not seem to affect the supply of revolving credit. In general, the negative impact of crime on credit suppliers decreases as the size of the debtor increases.

The importance (in terms of quality and quantity) of collaterals in credit contracts is higher in areas of high criminal intensity because both conditions of businesses are more opaque, and banks want to protect their own investments from the high risk of insolvency. Crime generates greater information asymmetry between banks and their customers; in the case of banks, it increases the chance of adverse selection in the time of evaluating the financing plans for customers, while in the case of customers there is an increase of moral hazard in fulfilling contracts. As to loans to large companies, these problems tend to present lesser information problems since they are relatively more transparent and efficient.

Education is an effective tool of social inclusion. With regard to the acquisition of education, according to the credentialist approach, a higher education degree reflects an individual’s skill. In the labor market, under conditions of incomplete information, the demand for labor relies on qualifications as an indication of the ability of workers. The worker, in turn, tries to obtain a higher level of education so as to secure a greater probability of receiving a higher salary. In this case, the differences in education levels reflect differences in the innate capacities of individuals.

According to the mainstream economic approach, it is possible to take action to reduce inequalities in education by lowering costs and, therefore, obstacles to accessing education. On the other hand, for the credentialist approach, it is inefficient to intervene in educational inequalities if the educational system rewards the best ones. While mainstream policies focus on access to education to give everyone the chance to earn more in the future, according to the credentialist approach, institutions must focus on making the education system efficient so that it rewards merit.

Empirical analyses have estimated the different factors that influence the acquisition of education; among the main ones are family background, the effectiveness of the education system, as well as the labor market in relation to the opportunity to train during their working career. A very topical element of social exclusion is the intergenerational effect of education. Income inequality leads to inequality in education levels. Beyond that, there is the persistence of intergenerational deprivation of education: deprivation of a parent increases the likelihood of deprivation of the children. In essence, the deprivation of education carries a lower expected income, a lower probability of children’s education, and a lower probability of employment. Deprivation of education or skills causes harm to individuals by predisposing them to social exclusion, but also hampers economic growth, as it limits the expansion of education, which is one of the main means to economic development.

The minimum level of education under which exclusion occurs is in fact dependent on both internal factors, such as the degree of development and the degree of inequality of the territory concerned, and on exogenous factors, such as socio-economic change at the global level. Certainly, the two types of factors interact, but it is good to consider them separately from the point of view of policy actions because the acquisition of an adequate level of education is a fundamental prerequisite for social inclusion.

In discussing inequality and poverty, this chapter has first focused on income inequality, following a classical approach complemented by a stochastic approach to the distribution of personal income. It has then devoted attention to the link between human development, social exclusion, and poverty, focusing on some theoretical and empirical dimensions of exclusion such as exclusion from labor market, financial market, and education.

In analyzing the process of human development, we have referred to Sen’s capability approach, examining a process of expanding resources that can be transformed into real opportunities available to individuals and communities. The transformation of resources in real freedoms to achieve desired objectives depends on factors of individual and social conversion, as well as on factors of choice leading each individual to actually implement available opportunities.

Social exclusion, as a condition, is characterized by being multi-dimensional, involving social and economic factors that affect both individuals and entire social groups. In summary, social exclusion and poverty appear to be an inability of individuals to participate in economic and civil life and gain access to social services. It is the result of the interaction between emerging factors of potential exclusion, the so-called drivers of exclusion, which may have a structural, institutional, and behavioral nature, and pre-existing vulnerability factors. This process tends to be cumulative, meaning it can create traps; drivers of a type of exclusion can become vulnerability factors for other types of exclusion (for instance, unemployment is certainly a driver of exclusion, but can also become a risk factor for financial exclusion). Traps can also occur because of the negative externalities that the social exclusion of an individual or a community can generate in relation to other subjects. If an individual resides in an area of high social disadvantage, s/he may have difficulty in accessing credit, while not having any personal risk factor. In this context, social exclusion seems to strike repeatedly and in a multi-dimensional way the most vulnerable subjects and regions.

Many thanks are due to the Handbook editors for their useful comments. The usual disclaimer applies.

Atkinson, A.B. 1998. ‘Social exclusion, poverty and unemployment,’ in: A.B. Atkinson & J. Hills (eds.), Exclusion, Employment and Opportunity. London: Centre for Analysis of Social Exclusion, London School of Economics, 1–20.

Beall, J. 2002. ‘Globalization and social exclusion in cities: framing the debate with lessons from Africa and Asia.’ Environment and Urbanization, 14 (1): 41–51.

Boor, M. 1980. ‘Relationship between unemployment rates and suicide rates in eight countries, 1962–1979.’ Psychological Reports (Missoula, MT), 47 (3):1095–1101.

Castells, M. 1998. End of the Millennium. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

Champernowne, D.G. 1973. The Distribution of Income Between Persons. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

D’Ippoliti, C. 2011. Economics and Diversity. New York: Routledge.

Elsner, W. 2013. ‘State and future of the ‘Citadel’ and of the heterodoxies in economics: challenges and dangers, convergences and cooperation.’ European Journal of Economics and Economic Policies: Intervention, 10 (3): 286–298.

European Commission. 2008. Financial Services Provision and Prevention of Financial Exclusion. Brussels: European Commission.

Gibrat, R. 1930. Les Inégalités Economiques. Paris: Librairie du Recueil Sirey.

Ibrahim, S.S. 2006. ‘From individual to collective capabilities: the capability approach as a conceptual framework for self-help.’ Journal of Human Development and Capabilities, 7 (3): 397–416.

Jackson, C. 1999. ‘Social exclusion and gender: does one size fit all?’ The European Journal of Development Research, 11 (1): 125–146.

Lee, F.S. 2012. ‘Heterodox economics and its critics.’ Review of Political Economy, 24 (2): 337–351.

Martins, N.O. 2011. ‘The revival of classical political economy and the Cambridge tradition: from scarcity theory to surplus theory.’ Review of Political Economy, 23 (1): 111–131.

Martins, N.O. 2012. ‘Sen, Sraffa and the revival of classical political economy.’ Journal of Economic Methodology, 19 (2): 143–157.

McGrew, A. 2000. ‘Sustainable globalization? The global politics of development and exclusion in the New World Order,’ in: T. Allen & A. Thomas (eds.), Poverty and Development into the 21st Century. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 345–364.

Milanovic, B. 2013. ‘Global income inequality in numbers: in history and now.’ Global Policy, 4 (2): 198–208.

Mill, J.S. 1848. Principles of Political Economy. London: Longmans, Green and Co.

Nussbaum, M.C. 2003. ‘Capabilities as fundamental entitlements: Sen and social justice.’ Feminist Economics, 9 (2–3): 33–59.

Okin, S. 1989. Justice, Gender and the Family. New York: Basic Books.

Pareto, V. [1897] 1964. ‘ Cours d’économie politique, ’ in: G. Busino (ed.), Oeuvres Complètes. Genève–Paris: Droz.

Platt, S. 1984. ‘Unemployment and suicidal behavior: A review of the literature.’ Social Science and Medicine, 19 (2): 93–115.

Putnam, R. 2000. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Robeyns, I. 2003. ‘Sen’s capability approach and gender inequality: selecting relevant capabilities.’ Feminist Economics, 9 (2–3): 61–92.

Say, J.-B. 1836. Cours Complet d’Économie Politique Pratique. Bruxelles: Dumont.

Sen, A.K. 1992. Inequality Re-examined. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Sen, A.K. 1996. ‘Employment, institutions and technology: some policy issues.’ International Labour Review, 135 (3–4): 445–471.

Sen, A.K. 1997. ‘Inequality, unemployment and contemporary Europe.’ International Labour Review, 136 (2): 155–171.

Sen, A.K. 1999. Development as Freedom. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Sen, A.K. 2000. Social exclusion: concept, application and scrutiny. Social development papers 1. Available from http://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/29778/social-exclusion.pdf [Accessed July 26, 2016]

Smith, A. [1776] 1976. An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, in: R.H. Campbell, A.S. Skinner, & W.B. Todd (eds.), The Works and Correspondence of Adam Smith, Vol. II, Oxford: Oxford University Press.