Figure 26.1 Non-linear multiplier-accelerator

Matías Vernengo

The discussion of economic fluctuations dates back to the nineteenth century, to the classical political economists. However, these scholars were essentially concerned with the process of capital accumulation, and did not develop a proper theory of cycles. Arguably, economic fluctuations in most pre-capitalist societies were irregular and highly related to shocks to agricultural production. Most discussions related to what eventually would become part of business cycle theory were related to the acceptance or rejection of Say’s law and the possibility of a general crisis. The marginalist revolution that brought the neoclassical model to the center of the economics discipline, in contrast, suggested that the system did have a tendency to the full utilization of resources, including labor. In this view, crises and eventually cycles were either deviations from the optimal output level or changes to the optimal level itself, caused by shocks in both cases—monetary in the former and real in the latter.

Keynesian economics resurrected the classical political economy notion that the system was prone to crises, and that it could settle at a stable and sub-optimal position in the long-run. Keynes did not advance a theory of the economic cycle in the General Theory (GT), and his discussion in that book suggests that shocks were central for him, particularly shocks that he referred to as the ‘marginal efficiency of capital’ (MEC) (Keynes 1936: 313). However, Keynesian scholars developed a family of models that incorporated Keynes’ principle of effective demand, in which business cycles occurred in the absence of shocks. Further, the trend, and fluctuations of economic growth were intertwined, and it was impossible to disassociate the process of economic growth and cycles.

The economic system, in this sense, was prone to fluctuations, and economic policy had to be geared towards reducing the negative effects of the downward phase of the cycle and to stimulate the boom. Shocks, both real and monetary, can still play a role in heterodox models of the cycle, but they essentially exacerbate the tendencies of an already unstable economy. These heterodox views of the economic cycle, based on endogenous mechanisms that generate fluctuations, were essentially abandoned by the mainstream of the economics discipline after the rise of monetarism in the 1960s and new classical economics and real business cycles in the 1970s. Nevertheless, heterodox scholars remain of the view that an endogenous theory of cycles is necessary to understand the inherent instability of capitalism.

The rest of this chapter is structured in three sections. The following section analyzes the contributions of the classical political economists, with an emphasis on the works in the Marxian tradition, which have been the most influential development within this framework. Particular attention is paid to the role of the predator-prey model in generating economic fluctuations. The following section looks at heterodox Keynesian models, starting with Keynes, and then with his followers. They emphasize the relevance of the interaction of the multiplier and accelerator mechanisms, and the role of structural instability, as the main sources of business fluctuations. A brief conclusion forms the final section.

Classical political economy discussions of crisis can be seen as the impetus for theories of economic fluctuations. David Ricardo and Robert Malthus famously debated the possibility of a general glut, with the former denying its possibility. The Ricardian view was that in the long-run a generalized over-production crisis could not occur, since supply created its own demand. For Ricardo this basically meant that generally production resulted from the desire to consume. In other words, supply by definition was the result of demand. Hence, for Ricardo, while crises could occur in the short-run since some products would not meet demand, in the long-run producers would learn from their mistakes and supply only goods which were socially useful, and that would provide them with the purchasing power to fulfill their own consumption desires. Ricardo suggested that nobody would continue to produce something for which there is no demand over the long-run. Note that while in Ricardo’s view capitalists re-invested all their savings, and capital was fully utilized, the same was not true for labor. The level of output was fixed in this classical model.

Marx was critical of Say’s law, and for that reason is probably the first relevant author to discuss the possibilities of recurring crises as an inherent feature of capitalist societies. The Ricardian view is grounded in what Marx referred to as the ‘simplest form of the circulation of commodities,’ or simple exchange, where commodities were produced for exchange for commodities, with money being just an intermediary, C-M-C′ (commodity-money-new commodity). In this case, Say’s law was operative, since it was true that production occurred as a result of a desire to consume. Yet, Marx suggested that, in capitalist societies, accumulation, and not consumption, is the basis of material production. In other words, capitalists produce to accumulate profits in monetary terms, or M-C-M′, and realization crises, the problem in the last leg of the transition from commodity to money (C-M′), might be a feature of the economy. While Say’s law would be valid in a simple reproduction system, it would be invalid in a capitalist economy.

By the middle of the nineteenth century, there was a more widespread understanding that economic crises are periodical in industrialized economies.1 Several scholars criticized Say’s law, most notably Malthus, Sismondi, and Rodbertus. These criticisms developed into what is sometimes referred to as under-consumptionist theories of crises. The most famous of the under-consumptionist theories was that of John Hobson, an anti-imperialist British economist who argued that as the process of accumulation accelerated and profits became concentrated in fewer hands, the opportunities for profitable investment were reduced, and the lack of demand would make it impossible to increase production on a larger scale. Both the role of under-consumption, particularly with Rosa Luxemburg and later Paul Sweezy, and of monopoly capital, with Rudolf Hilferding and afterwards with Paul Baran and Sweezy, would contribute to Marxian theories of crises. Marxian scholars have been, for the most part, the ones extending the old and forgotten tradition of classical political economy.

Marxian theories of the business cycle have a common thread—that is, the role of the rate of profit is the main variable to understand fluctuations. Profit squeeze theories, which became popular in the 1960s, suggest that in booms the reserve army of the unemployed shrinks, the bargaining power of workers will increase, and higher wages will tend to squeeze the profits of the capitalists, who will refrain from investing as a result. The crisis that ensues will also contain the seeds of the recovery, since as higher unemployment reduces the bargaining power of the labor force, wages will tend to fall behind, and the profit rate will recover, leading to a renewed process of accumulation.2

The main difference between alternative Marxian explanations of business cycle fluctuations is the mechanism by which the rate of profit changes over time. In addition, it is important to understand that these theories differ from long-term arguments about the effects of a profit squeeze on accumulation, and on the possibility of a generalized crisis of capitalism.3

Richard Goodwin’s contribution is one of the most idiosyncratic and probably one of the most important developments of Marxian ideas on the business cycle. Goodwin ([1967] 1982), adapting an idea from biological sciences, the so-called predator-prey model, notes that the fluctuations of the profit rate that are central to the explanation of cycles are also intrinsically connected to the process of economic accumulation and growth. The Goodwin model provides an example of cyclical growth—that is, the notion that the process of economic growth is highly unstable, and that fluctuations of economic activity are intrinsically connected to the process of capital accumulation and growth.

In Goodwin’s model investment is a function of profits, and in a booming economy with profits increasing, capital accumulates, and output and employment increase as well. However, as employment increases the economy moves towards full employment, and the share of wages in total income rises, reducing profits, and eventually has a negative impact on investment and employment. As profits fall, investment is reduced, and output and employment also decline. Yet, as unemployment increases, wage pressures diminish, and the whole cycle starts anew. The wage share acts as a predator, preying on profits,4 so to speak, which is the fuel of the economy.

Central to Goodwin’s argument is that savings out of profit determine investment. In a classical political economy fashion, all wages are consumed, while profits are saved and used for investment. Additionally, employment grows with output which, in turn, follows investment. Employment grows with capital accumulation, adjusted by the increase in labor productivity and the growth of the labor force. In other words, employment is directly related to profits, and inversely related to the wage share. In fact, Goodwin’s view of the labor market is perfectly compatible with mainstream marginalist views, in which firms demand more labor as it becomes less expensive. The wage share grows with real wages, and in the steady-state economy the wage share is constant, and the real wage grows with productivity, as in marginalist models. In Goodwin’s view, real wages increase in the proximity of full employment, which would be seen as the upper limit of the cycle.

In addition, in a downturn the wage share falls, not because the bargaining power of workers is reduced and real wages fall, but because real wages do not grow at the same pace than labor productivity, and that is what allows for the restoration of profitability; a very ‘un-Marxian’ result as noted by Goodwin ([1967] 1982: 169). The Goodwin model represents a hybrid of Marxian and neoclassical views, or what might be termed a Marxian-marginalist theory of the business cycle. The idea of the predator-prey, however, might be preserved in models in which the idea of distribution determined by marginal productivities and the tendency to full employment are abandoned, and in which the role of the bargaining power of the labor class assumes a more determinant role.5

One last family of Marxian theories warrants noting as part of the classical political economy tradition on the economic cycle, namely, Nikolai Kondratieff’s long cycles. This would be roughly 50-year cycles, longer than the decennial business cycles on which most theories concentrate. Like other theories, the basis for the cycle is that the process of replacing capital goods is not smooth. But Kondratieff suggested that major innovations tended to cluster and to lead to long cycles. Most economists find the empirical evidence for Kondratieff cycles to be weak, and sometimes the weaker notion of Kondratieff waves is used instead.6 The long wave theories of Kondratieff influenced the development of the Social Structure of Accumulation (SSA) approach, which emphasizes a broader set of variables to understand the process of economic development. In this sense, fluctuations are not only explained by changes in the rate of profit movements, but more importantly by the set of institutions that fosters capitalist accumulation.7

It is important to emphasize that classical political economy views on the cycle in general tend to assume that investment behavior, driven by the rate of profit, is the essential driving force of the economic cycle. In this view, investment is profit-led; in other words, firms increase or decrease capacity utilization on the basis of the rate of profit, or the returns to investment.8 However, many modern Marxian models assume that this is the actual rate of profit, while for classical political economy investment was related to the normal rate of profit. In that view, as noted by Garegnani (1992), firms would invest if the actual profit is above the normal rate of profit, which is equivalent to say that they need additional capacity to adjust to demand requirements. In other words, firms must adjust their capacity to demand, and there is a normal level of capacity utilization. In this view, expected demand might have a role in the determination of investment and, hence, the cycle. This view was later developed in Keynesian models in which an expansion in the wage share might be stimulating to the economy. In the alternative view, which was followed by certain Marxian scholars like Kalecki, the system would be wage-led, even though the effects of income distribution on output, employment, and growth may be ambiguous.

Keynesian theories of the business cycle start from the notion that changes in income equilibrate savings to investment ex post, and the level of economic activity is determined by effective demand. Further, the system does not have a tendency towards full employment. In that sense, the economy can fluctuate in the long-run, with wage and price flexibility, around a normal position that is below full utilization of labor and capital. Unemployment is the norm. Keynes was not directly concerned in the GT with business cycles per se, even though he discussed the issue towards the end of the book. His main concern was with what he referred to as ‘unemployment equilibrium.’

Keynes ([1936] 1964) argues that autonomous investment decisions are central for the determination of the level of output, and these are taken in an environment of true non-probabilistic uncertainty about the future. Investment is governed by long-term expectations, which could be interpreted as being affected by the prospects of future demand. The fluctuation of investment, associated with what Keynes referred to as animal spirits, leads to the fluctuation of the level of output and employment, basically following the multiplier process. Keynes suggested that it was the cyclical changes in investment, which he associated with the marginal efficiency of capital that determined business cycle fluctuations.9 Keynes ([1936] 1964: 317) thought, also in conventional fashion, that to revive investment was not easy, in particular because of “the uncontrollable and disobedient psychology of the business world” and also since the return of confidence was “insusceptible to control in an economy of individualist capitalism.” But he did not rely completely on ‘confidence fairies,’ to use a more modern expression.

The socialization of investment, by which Keynes ([1936] 1964: 375–376) meant basically public investment, was necessary to get the economy out of the crisis, but would, in his view, “be quite compatible with some measure of individualism, yet it would mean the euthanasia of the rentier.” The rentier class, to which Keynes belonged, lived from financial returns, and the idea of the euthanasia of rentiers basically meant maintaining relatively low rates of interest. Although Keynes’ reasons were essentially conventional, associated with stimulating investment which according to marginalist theory occurs at low rates of remuneration, the euthanasia of the rentier meant that debtors, in general, but in particular the state, would be less burdened and that would allow for the economy to be maintained closer to a permanent boom. After all, Keynes ([1936] 1964: 322) argued in Chapter 22 of the GT that the: “right remedy for the trade cycle is not to be found in abolishing booms and thus keeping us permanently in a semi-slump; but in abolishing slumps and thus keeping us permanently in a quasi-boom.” It is important to note, however, that cycles, in Keynes’ conception, depend on shocks, which are associated with the state of long-term expectations and the state of confidence, meaning that business cycles are essentially exogenous.

There is no explanation of the shocks, and of the reasons why advanced capitalist economies seem to go through persistent fluctuations. In that sense, mainstream economists suggest that demand shocks to either the goods market equilibrium or the monetary market can be seen as reasonably within the scope of what Keynes suggested caused the cycle. However, that would be a model in which there is no tendency to full employment as a result of income distribution and debt-deflation effects, and more in line with heterodox Keynesian views.10 It would fall to Keynes’ followers in Cambridge and Oxford to develop an endogenous theory of the cycle, that is, one that did not depend on external shocks.

Kalecki ([1933] 1971), who advanced the principle of effective demand independently of Keynes, and Harrod (1936), a disciple of Keynes, developed an early theory of the cycle based on the interaction of Keynes’ multiplier process with the concept of the accelerator. The American institutionalist economist John Maurice Clark developed the idea of the accelerator.11 The accelerator resulted from the institutionalists’ preoccupation with empirical evidence on business cycles, pioneered by Wesley Mitchell, the founder of the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER). The notion is relatively simple: firms will invest, that is, buy equipment and installations and increase the stock of capital, to the extent that future demand is expected to increase. In other words, firms will try to maintain a desired or normal capacity utilization level, which will mean a desired ratio of output to capital. Capacity or supply will adjust to demand, and investment will be dependent on expectations of future income, or derived demand.

The interaction of the multiplier and the accelerator provides a simple explanation for economic cycles that are endogenous, and that under certain conditions can be persistent and for that reason might not require external shocks to explain economic fluctuations, even if shocks do occur and are frequent. Kalecki ([1933] 1971) emphasized the role of time lags between the placing of investment, the demand for new equipment, and the delivery of the new equipment, indicating the dual role of investment as part of demand, but as creating productive capacity in the future. Further, Kalecki suggested that investment orders are a positive function of autonomous demand and a negative function of the existing capital stock. In other words, if demand is growing firms will add capacity and invest, but if capacity is already built and the existing stock of capital is large, they will not. Investment requires the maintenance of a particular ratio of the flow of income to the stock of capital. Note that capital goods depreciate, and, as a result, a certain amount is demanded just for replacement.

Assuming that expectations about future demand are high, then investment will increase and through the multiplier effect it will have a reinforcing effect on income. The increase in income, in turn, will lead, according to the accelerator, to an increase in investment, leading to an economic boom. However, as investment increases, eventually new investment orders will exceed the replacement requirements, and the capital stock will also rise. This will have a negative effect on the rate of increase in investment, and new investment orders will slow down first, and then decrease. The decreasing orders will have a negative impact on demand, and through the multiplier, lead to a reduction in the level of income, creating the conditions for a recession. Falling income will imply lower investment, following the accelerator, and even further collapse of income. In a depression, investment orders will collapse and at some point they will fall below the replacement requirements associated with depreciation, leading to a reduction in the stock of capital. Finally, the falling stock of capital will make the need for investment inevitable, and this will lead to more demand and a recovery.

The essential mechanism of the business cycle in the Kaleckian model is connected to the lags between the demand effect and the capacity effect of investment. Kalecki (1954) assumed that shocks will provide the initial spark for the business cycle, and the multiplier-accelerator mechanism will keep it going.12 He noted also that only under very specific circumstances will the cycle recur, and that additional shocks will be necessary to avoid a dampened cycle. Further, fluctuations will occur around levels of output which imply an average rate of unemployment considerably below the peak reached in the boom, and the existence of what he referred to as the reserve army of unemployed, following Marx, will be a characteristic of the cycle. In other words, fluctuations will occur around a normal position that involves significant unemployment, as Keynes argued.13

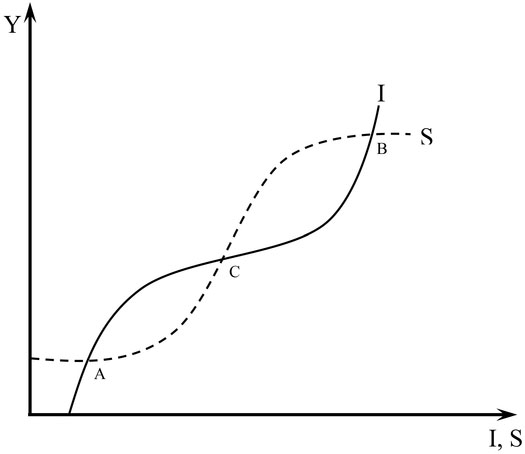

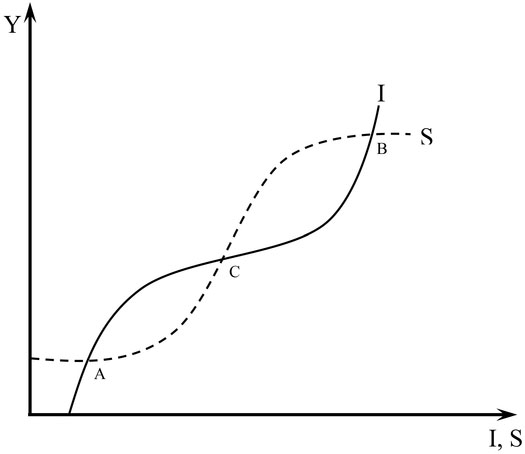

Kaldor (1940) developed a model, later formalized by Hicks (1950) and Goodwin (1951), which allowed for the economic cycle to recur even in the absence of external shocks. The central difference in the Kaldorian model was the introduction of non-linear investment and savings functions. The idea was not to deny the existence of stochastic shocks or time lags, but to demonstrate that the economic system will also fluctuate in their absence, and that in a broad sense the capitalist system was inherently unstable. In other words, Kaldor introduced a nonlinear accelerator and multiplier. At low levels of income, investment will not change much with an increase in income, since the large amount of spare capacity will preclude additional investment. Also, at high levels of income, investment will be insensitive to changes in income, since the capital goods sector that produces investment goods will be close to full capacity. The investment schedule is shown in Figure 26.1.

Further, the savings function too will be non-linear, with a high propensity to save—the inverse of the multiplier—at low and high levels of income, and a lower propensity to save at intermediate levels of income. The idea is that at low levels of income, the propensity to save is low, since consumption cannot fall below a certain minimum that is socially acceptable, and at higher levels of income the savings rate increases, and at very high levels of income the savings rate increases explosively, since the rich can save almost all their additional income. The nonlinear multiplier follows from different patterns of consumption associated with income distribution. The savings function will resemble the S-curve depicted in Figure 26.1.

Figure 26.1 Non-linear multiplier-accelerator

In this case, there may be multiple equilibria between investment and savings, and some will be unstable. Whenever investment (I) is bigger than savings (S), the multiplier process will imply higher income, and vice versa when investment is smaller than savings. In Figure 26.1, A and B will be stable equilibria, while C will be unstable, since whenever the income level is above A and B investment is smaller than savings, and income will decrease, while the opposite is true above C.

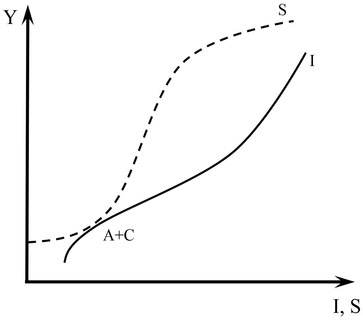

Further, Kaldor (1940) assumed that an initial shock would move one of the schedules. That is, both the investment schedule (I) and the savings curve (S) will shift generating the initial instability. Assume that the economy starts at the high output equilibrium at point B. Then the exhaustion of investment opportunities will lead to a shift of the investment curve upwards, meaning less investment (I) for the same level of income (Y). At the high level of income, consumption patterns will also change and the S schedule will move downward, implying less savings (S) at the same level of income (Y). The high income equilibrium level becomes unstable in a downward direction (B+C), as depicted in the graph on the right of Figure 26.2; for a given level of income above the equilibrium between I and S, I will be smaller than S as income will be decreasing. As the level of income decreases, however, and income collapses, the fall in investment leads to a situation in which the purchase of new equipment is insufficient to cover capital replacement needs. A shift of the whole investment schedule down and to the right, until it is tangent to the savings curve, as shown in the left-hand graph in Figure 26.2, will take place. In this situation, at the original level of income S will be smaller than I, and income will be increasing in the direction of the new equilibrium. The low level of income equilibrium will become upwardly unstable (A+C equilibrium), and the original situation will be re-established, with a continuous cycle.14

In the Kaldorian non-linear cycle model, once the economic system is perturbed, fluctuations will inherently recur as a result of the interaction between the multiplier and the accelerator. The system will be in perpetuum mobile. Goodwin’s (1951) limit-cycle model showed that the non-linear interaction between the multiplier and accelerator leads to regular fluctuations without the need for exogenous shocks, time lags, or particular parameter values.15 These models were essentially abandoned by the mainstream in the 1970s, not because they have theoretical or methodological flaws, or because of the empirical evidence favoring the multiplier and accelerator effects. The models were discarded with the rediscovery of the notion of the natural rate of unemployment, and the notion that the economic system is self-adjusting to full employment.16

Figure 26.2 Cyclical instability

Even though the multiplier and accelerator effects seem to be empirically relevant and point to the role of demand in economic fluctuations, it is important to understand that the Keynesian notion of the instability of capitalism is not completely illuminated by the models discussed so far. It is also important to note that the heterodox Keynesian business cycle models imply that the forces explaining fluctuations are also directly and intrinsically connected to structural changes and economic growth. Trend and cycle are to some extent inseparable.

The interaction of the multiplier and accelerator means that the trend, which depends on the accelerator, that is, on the adjustment of capacity (supply) to demand, is intrinsically connected to fluctuations. In this sense, one cannot separate cycles and growth, and Keynes’ notion that, to avoid the worst types of recession, policy should aim at maintaining a quasi-boom all the time makes sense. Note that demand forces, not supply conditions, determine the maximum level of output, below which the economy fluctuates.17

In addition, the Keynesian approach to the cycle based on the interaction of the multiplier and the accelerator suggests that the economic system is dynamically unstable—that is, not only does it regularly fluctuate around a sub-optimal level of activity, but also the system is within certain conditions that are structurally stable. This is the reason that Keynes ([1936] 1964: 249) suggests: “it is an outstanding characteristic of the economic system in which we live, that, whilst it is subject to severe fluctuations in respect to output and employment, it is not violently unstable.” Keynes emphasized the role of monetary and financial factors in the characterization of instability.

Vercelli (1984) argues that Keynes’ theory must be re-interpreted in light of the difference between the concepts of dynamic and structural instability. Dynamic instability is simply the divergence from equilibrium, while stability will be convergence. Harrodian knife-edge instability is the most evident example. Structural instability, on the other hand, is associated with the qualitative change in behavior of the system after being disturbed. The Minskian financial instability hypothesis (FIH) exemplifies the idea of structural instability. Vercelli (2000) argues that the degree of financial fragility can be measured as the minimum threshold of the shock required for inducing a firm into insolvency and leading it to bankruptcy.18 The behavior of the system is such that a small shock is able to change the qualitative behavior of firms, from stable to unstable, following Minsky’s (1986) notion that ‘stability is destabilizing.’ The behavior of the system is characterized by fluctuations that are cyclical although not regular, and this results from the endogenous properties of the system rather than exogenous shocks.19

Alternatively, the differences between the inter-war Gold Standard and the so-called Bretton Woods period (often referred to as the Golden Age of capitalism for its high rates of economic growth around the globe) are a good example of the difference between dynamically and structurally unstable economic systems. In both cases, the economy fluctuates around a demand-determined average level of output and employment. However, the inter-war Gold Standard system, with no clear hegemonic leader, forced countries to maintain relatively high rates of interest, and created a burden on indebted agents, including governments and thus reducing their ability to expand demand. On the other hand, during the Bretton Woods period, the existence of capital controls, which allowed for lower interest rates without fear of capital flight, and central banks committed to full employment policies, the economies of advanced countries fluctuated around positions that were closer to the full utilization of the labor force.

In both cases, the economy is dynamically unstable, within certain margins, but dynamically stable from a general perspective. Yet, in the inter-war Gold Standard system the change in the hegemonic center from the United Kingdom to the United States (US) led to a change in the qualitative behavior of the economy and to significant structural instability, leading to the Great Depression.20 In that sense policy regimes, in particular the functioning of the international monetary system are central to the Keynesian view for the determination of whether the economy will fluctuate around a position that is closer, or not, to full employment. In this sense, heterodox Keynesian theories of the cycle, like Marxian views reflected in the SSA approach, suggest that business cycles are not always the same in different historical circumstances.

Heterodox views of the business cycle build on the old classical political economy notion that the economic system is inherently unstable. Contrary to the mainstream view that the cycle is a result of shocks, either monetary or real, which affect the economy, heterodox scholars suggest that the system has mechanisms by which fluctuations are inherent and will occur even in the absence of shocks. Shocks obviously do occur, and demand or monetary shocks tend to be more common than real shocks. But it is difficult to explain the relative regularity of cycles if shocks are their only source.

Also, since the economy fluctuates around a normal capacity utilization that is only by chance the maximum level of capacity utilization, in fact a rare phenomenon, the shocks are non-mean reverting, that is, the economy does not necessarily return to the same trend. This accounts for the fact that Gross Domestic Product follows a random path that is not explained by real shocks affecting the optimal output level, as implied by real business cycle scholars.

Marxian models of the cycle emphasize the role of profits in the explanation of economic fluctuations. An important mechanism that allows for recurrent fluctuations is based on the predator-prey mechanism. The behavior of investment, which is dependent on the profit rate, and the effects of a growing economy on the bargaining power of workers and the wage share, are combined to create the conditions for cyclical movements. In the heterodox Keynesian view, output fluctuates because investment is affected by expected demand, leading through the accelerator to an adjustment of capacity to demand, but investment affects actual income through the multiplier. Higher than expected demand leads to higher income, and higher income leads to more demand, and vice versa when expected demand falls.

Both Marxian and heterodox Keynesian scholars tend to emphasize the broader institutional framework that makes capitalism unstable. While Marxian authors emphasize the relevance of what has become known as social structures of accumulation, Post Keynesian authors tend to emphasize the monetary and financial elements that produce instability. In many ways, these views remain compatible, even if some specific models are not and they emphasize different elements of the capitalist system.

Finally, the heterodox view of economic cycles suggests that cycles and growth are intertwined. That is, the process of growth and the wealth of nations occur concomitantly with booms and recessions. Cycles can be smoothed out by appropriate economic policy but they cannot be completely eliminated.

The author thanks the comments of the editors on a preliminary version of the paper.

1 For the most part, the pioneers of business cycle analysis were marginalists or proto-marginalists. Clément Juglar, among the proto-marginalist authors, is normally considered the pioneer of business cycle theory. Juglar emphasized the role of monetary factors in explaining crises and, in particular, the speculation and the up- and down-swings of business confidence. There is little theoretical discussion in his analysis of why prices increase during booms, and what causes over-production and sudden collapse.

2 There is a myriad of models in this vein with applications to the US and several other advanced capitalist economies. Sherman (1979) summarizes these views. An important contribution by Weisskopf (1979) argues that cyclical declines in the profit rate are central to explaining economic crises. For a more recent analysis along these lines see Bakir & Campbell (2006). Bakir & Campbell (2013) expand the analysis to encompass the effects of the rate of profit in the financial sector, which in their view becomes more relevant in the more recent fluctuations of the US economy.

3 Besides the cyclical profit squeeze, and the secular decline in the profit rate, associated with the rising organic composition of capital, the third type of crisis that can lead to a Marxian model of crises, and to a theory of business cycle, will be under-consumption. For Marxian models that try to adapt the Keynesian idea of effective demand, see Shaikh (1989).

4 Alternatively, one can think of wages being predatory to employment, which is how the Goodwin model is often portrayed. For a contemporary discussion applied to the US economy, see Barbosa-Filho & Taylor (2006) and see Taylor (2011) for an extended version including financial aspects.

5 Palley (2009) develops a Keynesian model in which the predator-prey dynamics plays a role.

6 Shaikh (1992) suggests that Marx’s theory of the secular decline of the profit rate is at the basis of long wave fluctuations. There is an extensive literature on the validity, or not, of Marx’s tendency of the falling rate of profit and the so-called Okishio Theorem, which is beyond the scope of this chapter.

7 Gordon et al. (1994: 18) argue, regarding the post-war social structure of accumulation, that: “The prosperity of the 1960s undermined the postwar capital-labor accord by giving labor and other non-capitalist groups greater economic and political power, thereby destabilizing one of the principal institutional arrangements that had made the long boom possible.” So the relative strength of the labor force, and the institutions associated with the international monetary regime of Bretton Woods, that included capital controls and allowed for low interest rates were all central elements of the relatively benign cycles of this era. The classic discussion of SSA is Bowles et al. (1983), and the contributions in Kotz et al. (1994). For a recent discussion of the collapse of the neoliberal SSA and its consequences for the last crisis in the US see Kotz (2013).

8 In a sense, if causality comes from profits, which correspond to savings, to investment, then essentially the logic of Say’s law prevails.

9 On the necessity of breaking with the marginalist theory of distribution in order to show that the system does not have a tendency to full employment see Camara-Neto & Vernengo (2012).

10 Traditional marginalist arguments based on Keynes and Pigou effects, the so-called real balance effects, show that the economic system can have a tendency to full employment with flexible prices. In Chapter 19 of the GT, Keynes shows that a reduction in wages and prices might lead to worsening income distribution, lower spending, and lower output and employment, as well as bankruptcy of debtors and the collapse of investment. In both cases, the system will not tend to full employment, and wage flexibility can make things worse.

11 For a discussion of Clark’s views on the multiplier-accelerator interaction see Fiorito & Vernengo (2009). The interaction of the multiplier and the accelerator as the main mechanism for explaining the cycle was at some point accepted by proponents of the neoclassical synthesis, like John Hicks and Paul Samuelson. For a recent application of the multiplier-accelerator model to the US economy see Baghestani & Mott (2014).

12 The shocks will be propagated by the multiplier-accelerator mechanism. The methodology of separating the impulse that leads to the cycle from the propagation mechanism was devised by Ragnar Frisch and Eugene Slutzky and is dominant in mainstream economics, even though the propagation mechanism rarely includes the multiplier-accelerator mechanism. In mainstream models, shocks to demand or to supply lead to a readjustment to equilibrium; in the case of the latter, that is, real shocks, the actual equilibrium of the economy moves. In that sense, models that emphasize demand shocks suggest that cycles are deviations from the optimal level, while real business cycles (RBC) imply that the cycle is a change of the optimal level itself. For monetary and real mainstream cycle models see Erceg (2008) and McGrattan (2008), respectively.

13 Kalecki ([1943] 1971) would additionally suggest in his famous ‘Political Aspects of Full Employment’ that political economy factors are all central in determining whether an economy will fluctuate around full employment. In his view, capitalists have a vested interest in maintaining a certain amount of unemployed workers in order to reduce their bargaining power. This has led to a prolific literature within the mainstream on political business cycles. In heterodox circles, the Kaleckian idea has been seen as more relevant to understand the social basis of sound finance, and austerity policies, than as the basis for understanding output fluctuation.

14 For a detailed presentation of the model and the further theoretical developments of the Kaldorian non-linear cycle see Targetti (1992). The Kaldorian model can be seen as a simple prototype of more complex non-linear models.

15 For a modern presentation of heterodox Keynesian models of the business cycle, extended to deal with debt issues, and emphasizing both multiplier-accelerator and predator-prey mechanisms see Palley (2009).

16 The mainstream, on the contrary, suggests that supply conditions determine the capacity limit, often associated in modern macroeconomics to Milton Friedman’s natural rate of unemployment. Friedman (1968: 2) cites the Pigou effect, but none of the replies to its limitations like, for example Kalecki (1944), the basis for his argument to be the tendency to a natural rate of unemployment. Probably the most important development in this respect was the development of RBC theories, and the notion that cycles are equilibrium reactions to stochastic shocks to the economy, and the evidence presented by Nelson & Plosser (1982) that output follows a random path. This has created a notion that cycles are better understood as stochastic shocks, and deviations of the optimal level, that is, a changing natural rate. Note, however, that this is predicated on the notion that the relevant shocks are supply-side shocks, but it is very hard to believe that the Great Depression, or the more recent Great Recession were caused by supply-side shocks. It would be more reasonable to assume that demand shocks affect an economy that fluctuates around sub-optimal levels, and that the very idea of the natural rate should be abandoned (Galbraith 1997). In that sense, while shocks play a role, it is clear, given their continued empirical relevance, that multiplier and accelerator effects do matter.

17 In this case, the interaction of the multiplier and the accelerator is used to obtain the normal level of output, in a supermultiplier model. These models bring together elements of the old classical political economy tradition with the ideas of heterodox Keynesians. For these, see Serrano (1995) and Bortis (1997).

18 In his pure flow model, this financial fragility measure is simply associated with a fall in profits or an increase in interest rates. For firms there is a threshold of financial fragility beyond which they do not wish to go. More importantly, following Hyman Minsky, Vercelli (2000: 146) suggests that firms that are in a safe zone regarding financial fragility will, as a result of competition, invest and incur more fragile financial structures, moving from hedge, to speculative, and from that to Ponzi situations. This view is central within Post Keynesian theories of the cycle.

19 Vercelli suggests that the model has similarities with Keynesian accelerator-multiplier models, in particular with the Goodwin non-linear cycle. It is worth noticing that Minsky’s PhD dissertation did rely on the interaction between the multiplier and accelerator mechanisms (Minsky 2004). Regarding the endogenous nature of fluctuations, Minsky (1986: 324) argues that: “A sophisticated, complex, and dynamic financial system . . . endogenously generates serious destabilizing forces so that serious depressions are natural consequences of noninterventionist capitalism.” Most discussions of Minsky’s model are related to financial crises rather than as part of a theory of the business cycle. For a short exposition of Minsky’s crisis theory see Wray (2011).

20 Kindleberger’s ([1973] 1986) hegemonic stability theory suggests that the absence of a clear hegemon— being able to act as an international lender of last resort and as a source of demand in distress conditions— causes instability. This can be seen as an example of structural instability, and a broader explanation for the Great Depression.

Baghestani, H. & Mott, T. 2014. ‘Asymmetries in the relation between investment and output.’ Journal of Post Keynesian Economics, 37 (2): 357–365.

Bakir, E. & Campbell, A. 2006. ‘The effect of neoliberalism on the fall in the rate of profit in business cycles.’ Review of Radical Political Economics, 38 (3): 365–373.

Bakir, E. & Campbell, A. 2013. ‘The financial rate of profit: what is it, and how has it behaved in the United States?’ Review of Radical Political Economics, 45 (3): 295–304.

Barbosa-Filho, N.H. & Taylor, L. 2006. ‘Distributive and demand cycles in the U.S. economy – a structuralist Goodwin model.’ Metroeconomica, 57 (3): 389–411.

Bortis, H. 1997. Institutions, Behaviour and Economic Theory: A Contribution to Classical-Keynesian Political Economy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bowles, S., Gordon, D., & Weisskopf, T. 1983. Beyond the Wasteland: A Democratic Alternative to Economic Decline. Garden City, NY: Anchor Press/Doubleday.

Camara-Neto, A.F. & Vernengo, M. 2012. ‘Keynes after Sraffa and Kaldor: effective demand, accumulation and productivity growth,’ in: T. Cate (ed.), Keynes’s General Theory: Seventy-Five Years Later. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar, 222–237.

Erceg, C. 2008. ‘Monetary business cycle models (sticky prices and wages),’ in: S. Durlauf & L. Blume (eds.), The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics, 2nd online edn. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Fiorito, L. & Vernengo, M. 2009. ‘The other J.M.: John Maurice Clark and the Keynesian Revolution.’ Journal of Economic Issues, 43 (4): 899–916.

Friedman, M. 1968. ‘The role of monetary policy.’ American Economic Review, 58 (1): 1–17.

Galbraith, J.K. 1997. ‘Time to ditch the NAIRU.’ Journal of Economic Perspectives, 11 (1): 93–108.

Garegnani, P. 1992. ‘Some notes for an analysis of accumulation,’ in: J. Halevi, D. Laibman, & E. Nell (eds.), Beyond the Steady State: A Revival of Growth Theory. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Goodwin, R. 1951. ‘The nonlinear accelerator and the persistence of business cycles.’ Econometrica, 19 (1): 1–17.

Goodwin, R. [1967] 1982. ‘A growth cycle,’ in: R. Goodwin, Essays in Economic Dynamics. London: Macmillan.

Gordon, D., Edwards, R., & Reich, M. 1994. ‘Long swings and stages of capitalism,’ in: D. Kotz, T. McDonough, & M. Reich (eds.), Social Structures of Accumulation: The Political Economy of Growth and Crisis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Harrod, R. 1936. The Trade Cycle: An Essay. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Hicks, J.R. 1950. A Contribution to the Theory of the Trade Cycle. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kaldor, N. 1940. ‘A model of the trade cycle.’ Economic Journal, 50 (197): 78–92.

Kalecki, M. [1933] 1971. ‘Outline of a theory of the business cycle,’ in: Selected Essays on the Dynamics of the Capitalist Economy, 1933–1970. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1–14.

Kalecki, M. [1943] 1971. ‘The political aspects of full employment,’ in: Selected Essays on the Dynamics of Capitalist Economies, 1933–1970. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 138–145.

Kalecki, M. 1944. ‘Professor Pigou on “The Classical Stationary State”: a comment.’ Economic Journal, 54 (213): 131–132.

Kalecki, M. 1954. Theory of Economic Dynamics. London: George Allen and Unwin.

Keynes, J.M. [1936] 1964. The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

Kindleberger, C.P. [1973] 1986. The World in Depression, 1929–1939. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Kotz, D. 2013. ‘Social structures of accumulation, the rate of profit, and economic crises,’ in: J. Wicks-Lim & R. Pollin (eds.), Capitalism on Trial: Explorations in the Tradition of Thomas E. Weisskopf. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

Kotz, D., McDonough, T., & Reich, M. 1994. Social Structures of Accumulation: The Political Economy of Growth and Crisis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

McGrattan, E. 2008. ‘Real business cycles,’ in: S. Durlauf & L. Blume (eds.), The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics, 2nd online edn. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Minsky, H. 1986. Stabilizing an Unstable Economy. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Minsky, H. 2004. Induced Investment and Business Cycles. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

Nelson, C.R & Plosser, C.I. 1982. ‘Trends and random walks in macroeconomic time series: some evidence and implications.’ Journal of Monetary Economics, 10 (2): 139–162.

Palley, T. 2009. The simple analytics of debt-driven business cycles. Political Economy Research Institute, University of Massachusetts at Amherst Working Paper No. 200.

Serrano, F. 1995. ‘Long period effective demand and the Sraffian supermultiplier.’ Contributions to Political Economy, 14 (1): 67–90.

Shaikh, A. 1989. ‘Accumulation, finance, and effective demand in Marx, Keynes, and Kalecki,’ in: W. Sem-mler (ed.), Financial Dynamics and Business Cycles: New Perspectives. Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe, 65–86.

Shaikh, A. 1992. ‘The falling rate of profit as the cause of long waves: theory and empirical evidence,’ in: A. Kleinknecht, E. Mandel, & I. Wallerstein (eds.), New Findings in Long Wave Research. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 174–195.

Sherman, H. 1979. ‘A Marxist theory of the business cycle.’ Review of Radical Political Economics, 11 (1): 1–23.

Targetti, F. 1992. Nicholas Kaldor: The Economics and Politics of Capitalism as a Dynamic System. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Taylor, L. 2011. ‘Growth, cycles, asset prices and finance.’ Metroeconomica, 63 (1): 40–63.

Vercelli, A. 1984. ‘Fluctuations and growth: Keynes, Schumpeter, Marx and the structural instability of capitalism,’ in: R. Goodwin, M. Krüger, & A. Vercelli (eds.), Nonlinear Models of Fluctuating Growth. Berlin: Springer-Verlag, 209–231.

Vercelli, A. 2000. ‘Structural financial instability and cyclical fluctuations.’ Structural Change and Economic Dynamics, 11 (1): 139–156.

Weisskopf, T. 1979. ‘Marxian crisis theory and the rate of profit in the postwar U.S. economy.’ Cambridge Journal of Economics, 3 (4): 341–378.

Wray, L.R. 2011. ‘Minsky crisis,’ in: S. Durlauf & L. Blume (eds.), The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics, 2nd online edn. Palgrave Macmillan.