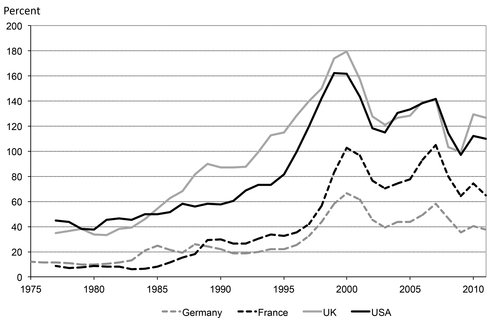

Figure 28.1 Stock market capitalization as a share of GDP: Germany, France, UK, and US, 1975–2011 Source: Beck et al . (2000; updated in 2013) author’s calculation.

Petra Dünhaupt

Marx highlighted the contradictions of capitalism, and argued that capitalism is but a stage on the way to a final societal form (Wallerstein 1974). Despite its contradictions and potential limits, capitalism continues to survive, by periodically redesigning and renewing its structure. Followers of Marx categorized these developments within capitalist history into different stages or periods, elaborating on the weaknesses of the system. Thus, the tendency of crisis plays a central role in Marxian tradition, exposing the limitations of the system and forcing new periods of capitalist development (Clarke 1994). The theory of capitalism can be approached by three different levels of analysis, one of which is a stage theory that analyzes the structural manifestations of the law of value in the stages of mercantilism, liberalism, and imperialism (Albritton 1986).1 The analysis of different stages of development is also of central importance in the Post Keynesian tradition. Institutions have a profound impact on economies and hence economies need to be regarded from a historical perspective (Kriesler 2013).

Since the 1980s, the financial sector and its role have increased significantly. This development is often referred to as financialization. Authors working in the heterodox traditions have raised the question whether the changing role of finance manifests a new era in the history of capitalism.

The first section of the chapter provides some general discussion on the term financialization and presents some stylized facts, which highlight the rise of finance. The second section begins with a brief review of the Marxian argument that capitalism is prone to crisis. Also reviewed are two schools of thought in the Marxian tradition—the Social Structure of Accumulation (SSA) approach and the Monthly Review school—which consider financialization as the latest stage of capitalism. Both highlight the contradictions imposed by financialization that disrupt the growth process as well as the fragilities imposed by its growth regime.2 The third section examines Post Keynesian theory, which emphasizes potential destabilizing factors that are germane to the phenomenon of financialization and the finance-led growth regime. The last section provides a comparative summary.

As stressed by Epstein (2005), financialization is one of three terms often used to characterize the past three decades of capitalism—the other two being neoliberalism and globalization. He defines financialization as “the increasing role of financial motives, financial markets, financial actors and financial institutions in the operation of the domestic and international economies” (Epstein 2005: 3). According to Dore (2008: 1097),

‘Financialization’ is a bit like ‘globalization’—a convenient word for a bundle of more or less discrete structural changes in the economies of the industrialized world. As with globalization, the changes are interlinked and tend to have similar consequences in the distribution of power, income, and wealth, and in the pattern of economic growth.

Financialization has many dimensions and relates to numerous different economic entities (Stockhammer 2013; Epstein 2015). One key dimension is the spectacular rise of the financial sector. Greenwood & Scharfstein (2013) report a massive growth of the financial sector over the past 30 years in the United States (US), measured either by the financial sector’s share of Gross Domestic Product (GDP), the volume of financial assets, employment, and average wages in the financial sector. But the growth of finance is not specific to the US; similar developments can also be found in other OECD countries although not as extreme as in the US (Philippon & Reshel 2013). The rise of the financial sector also manifests itself through profit shares. In the US, the share of total profits attributable to financial corporations has risen constantly: its share amounted to 13 percent on average in the 1960s, in the 2000s it increased to an average of 28 percent, and reached a peak in 2002, of 37 percent.3 Recent research shows a similar trend for many OECD countries,4 though with a few exceptions—for example, Germany (Detzer et al. 2013).

Figure 28.1 Stock market capitalization as a share of GDP: Germany, France, UK, and US, 1975–2011 Source: Beck et al . (2000; updated in 2013) author’s calculation.

The rise of the financial sector is also mirrored by the rise in financial activity compared to real productive activity (Stockhammer 2013). Figure 28.1 shows the stock market capitalization as a share of GDP for Germany, France, the UK, and the US for the period from 1975 to 2011. Stock market capitalization has grown rapidly in all countries since the mid-1980s, and even more so since the mid-1990s. In the UK and US, since the early or mid-1990s, stock market capitalization has outpaced GDP significantly.5

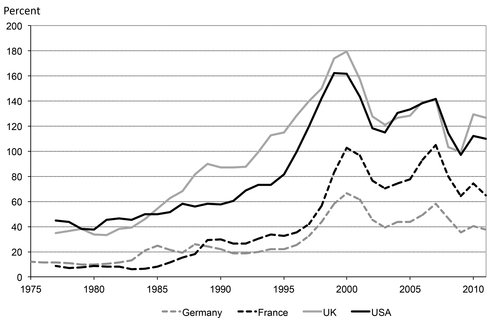

Figure 28.2 presents the stock value traded as a share of GDP for the same countries and time period. The change in this indicator is even more pronounced: since the mid-1990s, it has risen in all countries. In the UK and especially in the US, the trading activity has picked up tremendously, exceeding GDP over three (the UK in 2008) or four times (the US in 2009).

A further dimension of financialization relates to the rise in financial activity and financial orientation pursued by non-financial corporations. The rise in the shareholder value movement as a concept of corporate governance changed managerial focus from the long-term growth objective of the firm to the short-term objective of favoring shareholders’ interests (Stockhammer 2004; Lin & Tomaskovic-Devey 2013; Epstein 2015). The increase in non-financial corporations’ engagement in financial activities is also reflected in the following data.

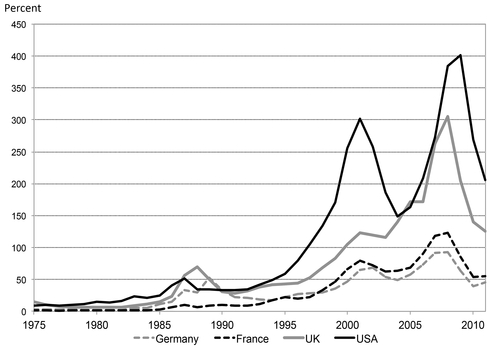

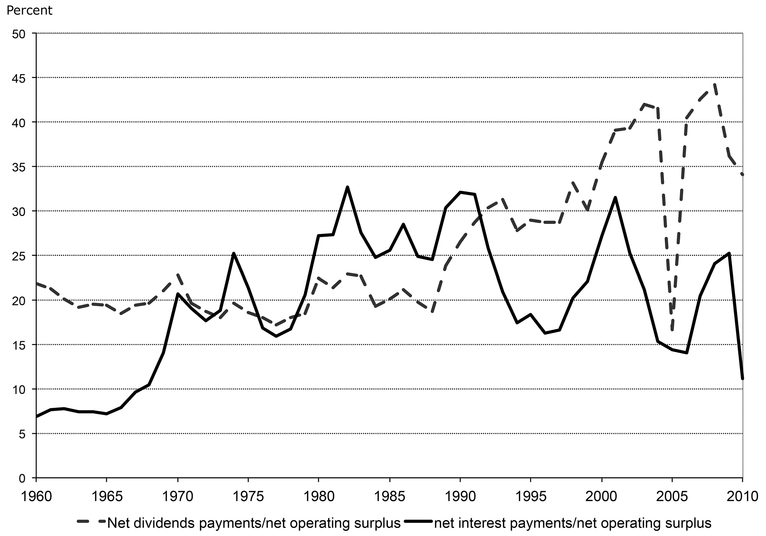

Figure 28.3 shows net dividends and net interest payments as a share of net operating surplus for US non-financial corporations from 1960 to 2010. Until the mid-1980s, dividend payments as a share of net operating surplus fluctuated around 20 percent; yet, by the mid-2000s it was over 40 percent. In contrast, net interest payments as a share of the net operating surplus has followed a downward trend since the early1990s—this is partly attributed to the high interest rate policy in the US. However, in 2000, the proportion of net interest payments recovered temporarily, reflecting high debt levels related to the ‘new economy boom’ (ECB 2012).

Figure 28.2 Stock value traded as a share of GDP: Germany, France, UK, and US, 1975–2011 Source: Beck et al. (2000; updated in 2013) author’s calculation.

Moreover, non-financial corporations heavily relied on stock repurchases to increase stock prices. According to Lazonick (2010, 2011), between 2000 and 2009 S&P 500 companies spent 58 percent of their net income to repurchase their own stocks and disbursed 41 percent as dividends. According to the European Central Bank (ECB 2007), the increase in dividend payments and stock buybacks are also a common practice undertaken by firms in the Euro area. Moreover, it is reported that those non-financial companies investing in their own equity curtailed real investment in productive capacity. Taken together, non-financial corporations have replaced the old strategy of ‘retain and invest’ with ‘downsize and distribute’ (Lazonick & O’Sullivan 2000).

Finally, another aspect of financialization that appears in many OECD countries is the rise in debt in different sectors (Epstein 2015). Particularly household debt relative to disposable income has risen sharply, as illustrated in Table 28.1 for Germany, Greece, Japan, the UK, and the US for the years 1995, 2000, 2005, and 2010. All countries considered here have a tendency of rising debt ratios from the mid-1990s to the Great Recession. High household debt ratios are potential sources of instability, since in a recession it might be difficult to service debt (Stockhammer 2013).

Figure 28.3 Net dividends and net interest payments as a share of net operating surplus of non-financial corporations: US, 1960−2010 Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA), NIPA tables; author’s calculation.

Table 28.1 Household debts as a per centage of net disposable income

Though Marx himself never developed a full-fledged crisis theory, he seems to “associate crises with the tendency for the rate of profit to fall, with tendencies to overproduction, underconsumption, disproportionality and overaccumulation with respect to labour” (Clarke 1994: 7). Central to Marxian macrotheory are the capitalist mode of production and the ‘circuits of capital.’ The mode of production is made by the forces and social relations of production, whereas the circuits of capital describe the stages of the capital accumulation process (Crotty 1986; Foley & Duménil 2008).

In the beginning of a production process (circuit one), the capitalist invests a certain amount of capital consisting of constant capital (M), the means of production, and variable capital, labor. During the production process (circuit two), the invested capital is transformed, creating surplus value—the value of the created commodity (C) exceeds the original value by a surplus. Finally, the commodities are sold and turned into money (M′ and M′ > M) (circuit three) (Marx 1887). From this follows Marx’s famous short schema: M-C-M′.

Marxian crisis theories address the variables in the circuits of capital framework as well as the institutional foundations of the circuits (Kenway 1983; Crotty 1986; Evans 2004). There are three major mechanisms that supposedly lead to a crisis. The first mechanism relates to the tendency of the falling rate of profit. Following Marx’s reasoning, during the capital accumulation process the organic composition of capital, which is defined as the ratio of constant capital to variable capital, increases. This, however, leads to a decline in the rate of profit, which is defined as the ratio of surplus value to total capital. Therefore, in the long-run, a rise in the organic composition of capital results in a fall in the rate of profit. The second mechanism potentially leading to a crisis relates to the distribution of income and under-consumption. Generally, workers spend all of their income on consumption. Hence, a redistribution of income at the expense of labor leads to a decline in demand for the produced commodities and, given the mismatch in supply and demand, ultimately to a failure to realize surplus value. The third mechanism potentially contributing to crisis relates to power relations. Here, a decline in the ‘industrial reserve army’ strengthens workers’ bargaining power vis-à-vis capitalists, probably leading to higher wages. A rise in the share of labor income potentially contributes to a decline in the rate of profit—that is, a ‘profit squeeze’—and hence to a fall in the rate of accumulation (Weisskopf 1992).

In the following, two schools of thought in the Marxian tradition, which consider financialization as the latest stage of capitalism, are examined in detail.

SSA theory conceptualizes capitalism in consecutive cycles, each lasting about 50–60 years. These cycles, or stages, are divided into phases of growth and stagnation. A crisis follows from stagnation; it constitutes the beginning of a new SSA (McDonough et al. 2010). SSA theory seeks to identify the institutional arrangements that support economic expansion. Here, institutions refer to a set of transnational and international organizations or customs—for example, the World Bank or the bargaining power of trade unions (Lippit 2010). SSA theorists describe their conceptualization as a mixture of Marxian and Keynesian economics. In line with Marxian economics, crisis tendencies emerge as a result of class struggle—that is, conflicts between capitalists and workers or within the capitalist class—and become an obstacle to further accumulationn. Similarly to Keynesian economics, SSA theory acknowledges that volatile investment decisions are shaped by expectation.

Recent work defines “SSA as a coherent, long-lasting institutional structure that promotes profit-making and serves as a framework for capital accumulation” (Kotz & McDonough 2010: 98). Based on this definition, Kotz & McDonough (2010) argue that since the early 1980s a new SSA—global neoliberalism—is in place. The neoliberal institutional structure is characterized by a free market ideology, which involves the demise of state regulatory structures and a shift of power from labor to capital. At a global level, the neoliberal SSA is characterized by a tremendous rise in cross-border movements of goods and capital, and the geographical extension of global production chains. At a domestic level, the neoliberal SSA changes the capital-labor relation; above all, the weakening of trade union bargaining power, while labor relations also change considerably. A further defining feature is a reconfiguration of the role of the state. The belief in the self-adjustment of markets has led to the dismantling of the welfare state, reducing tax rates, deregulation, and privatization of state-owned enterprises.

Kotz (2011) elaborates on historical circumstances that enabled the emergence of neoliberalism. The previous SSA is often referred to as ‘regulated capitalism’6 in which the state played an active role in regulating economic activity, both at the domestic and global level. Moreover, while welfare states were developing, there was a compromise between capital and labor (Kotz 2011). This SSA fell into a crisis in the 1970s. Consequently, it was replaced by the neoliberal SSA. According to Kotz (2011), the crisis of the ‘regulated capitalism’ SSA together with the rise in global economic integration, the belief in the free market doctrine, and the declining threat from the socialist countries are all key causes for the global neoliberal SSA to emerge. Further, he argues that the neoliberal institutional environment served as a favorable setting for financializa-tion to develop.

Though neoliberalism and the deregulation of the financial sector paved the way for financialization, it is argued that “financialization is an ever-present tendency in corporate capitalism” (Kotz 2011: 15). In this view, financialization refers to the rise of the financial sector and its changing role. In the past, the financial sector’s core business involved activities supporting the non-financial sector—for example, the provision of loan-based finance. During the neoliberal SSA, the financial industry detached itself from its core business and increasingly engaged in financial market-based activities. As a result, financial corporations increased their share in corporate profits.

SSA theory suggests that each stage of capitalism has a main contradiction with respect to economic growth, which eventually leads to a crisis (Kotz 2008, 2011). The contradictions of the neoliberal SSA are in one way or another related to financialization.

The institutional structure of the neoliberal SSA provides on the one hand a favorable environment for the creation of surplus value, while on the other hand it creates a problem for its realization, given the redistribution of income from labor to capital and the rise in income inequality. Two features that relate to financialization resolved the realization problem: first, the financial sector’s increasing engagement in speculative and risky financial market activities, and second, the rising occurrence of asset price bubbles. The redistribution of income towards profits and the increase in top income shares resulted in a vast amount of investable funds, which exceeded available productive investment opportunities and hence contributed to the emergence of asset bubbles. In light of these asset bubbles, households’ consumption was increasingly financed through debt and was based on the wealth effect (Kotz 2009).

Turning back to traditional Marxian crisis theories, at first glance the realization problem of surplus value during the neoliberal SSA appears as a crisis of under-consumption. However, the lack of demand was compensated by debt-financed consumption. Thus, the structural crisis of the neoliberal SSA can be considered as a crisis of over-investment (Kotz 2012). Over-investment refers to an excess demand for fixed capital in relation to the level of aggregate demand and can be prompted by asset bubbles. In light of rising debt-financed consumption by households, firms’ investment in capital stock rises to match the increase in consumption demand. Further, firms’ excess expectation regarding future profitability might also lead to a rise in investment spending. However, when the bubble bursts, firms’ capacity to repay debts diminish and consumption spending declines, but excess fixed capital remains (Kotz 2013).

During the neoliberal SSA, economic growth was generated, on the one hand, by the rise in debt-financed consumption to compensate for wage stagnation caused by neoliberalism and, on the other hand, by financial speculation and asset bubbles. That said, economic expansion in the neoliberal era depends on debt and asset bubbles (Kotz 2008) and the world economic crisis seems to mark the end of the neoliberal SSA (Kotz 2011).

The Monthly Review school relates financialization to economic stagnation. Inspired by Kalecki’s work on monopolization and investment, Steindl (1952) seeks to explain economic stagnation by linking the emergence of oligopolistic industries to a reduction in investment expenditure and, hence, to a decline in overall economic activity. Baran & Sweezy (1966) further elaborate on the stagnation thesis. In their view, the emergence of large corporate enterprises in oligopolistic and monopolistic industries leads not only to widening profit margins but also to a rise in the overall profit share and economic surplus.7 However, corporations face a dilemma. On the one hand, they seek to maximize profits and accumulate capital. On the other hand, they face problems in maintaining their profit margins and hence avoiding over-production and price reductions. Such a tendency results in a reduction in capacity utilization (Foster 2007). Ultimately, the economy falls into stagnation. Though monopolistic corporate enterprises generate huge surpluses, investment in capital stock remains low.

According to Foster & McChesney (2009), since the early 1970s, a crisis of over-accumulation and stagnation has appeared repeatedly, while at the same time the ‘financial superstructure’ has been growing. From the 1970s onwards, corporations started to channel surpluses into financial products instead of investing in fixed capital goods (Magdoff & Sweezy 1987). The money that was channeled into financial markets contributed to asset price inflation. Due to low investment in capital stock, growth was mainly generated through the debt-financed consumption of the household sector via the ‘wealth effect.’ Debt levels of other sectors of the economy increased as well, which led to a rise in instability of the economy as a whole (Foster 2008).

Foster (2006, 2007, 2008, 2010a, b) argues that by the late 1970s, capitalism entered a new phase, which he calls ‘monopoly-finance capital.’ The defining features of this phase are, among others, the accelerating increase in financial bubbles and financial speculation. Though profits of financial corporations have risen as a share of total corporate profits, Foster argues that the divide between financial and non-financial corporations has become less clear, given the increasing reliance of non-financial corporations on financial activities. Moreover, he observes the rise in income inequality as another defining feature, which generates a rise in households’ indebtedness induced by stagnating or falling real wages. According to Foster (2007), a more unequal distribution of income is a prerequisite for the functioning of monopoly-finance capital, given the “demand for new cash infusions to keep speculative bubbles expanding.” Foster (2007) thus regards neoliberalism as “the ideological counterpart of monopoly-finance capital” reflecting “to some extent the new imperatives of capital brought on by financial globalization.”

In summary, the main argument brought forward by the Monthly Review school is that it is stagnation that generates financialization. The genuine problem from this perspective is “the system of class exploitation rooted in production” (Foster 2008). Recalling Marx’s schema, it appears that M leads to M′, leaving out the production of commodities (Foster & McChesney 2009).

Post Keynesian economics rests on the principle of effective demand, which determines the level of output and employment. Fundamental uncertainty and expectations are defining features of the capitalist monetary production economy, which is shaped by social norms and institutions. Class and power relations determine income and wealth distribution (Arestis 1996; Stockhammer 2015b). With these core theoretical and methodological commitments, it follows that there are three main forces that can potentially destabilize the economy (Goda 2013): an increase in uncertainty, the endogeneity of money and financial fragility, and changes in income distribution.

In a world of fundamental uncertainty, entrepreneurs’ investment decisions are subject to expectations about future profitability. In an uncertain monetary production economy, individuals might restrain from consumption and investment and hold their money in liquid assets (Ferrari-Filho & Camargo Conceicao 2005).

Hyman Minsky (1986) developed the financial instability hypothesis that links the role of pro-cyclical credit to the business cycle, and that increasing instability renders an economy prone to crisis. When an economy is booming, investors become more optimistic about their future investments and, therefore, they are keen to borrow and credit expands. The lenders also have positive expectations about the future and become more willing to lend, even for high-risk investment projects. Minsky emphasizes the behavior of borrowers who increase their debts during the boom to buy assets. The underlying motive is to exploit short-term capital gains that result from the difference in increasing asset prices and the interest rates paid on the borrowed funds. However, the investors’ sentiments change when the economy slows down, because the interest paid on the borrowed funds might possibly exceed the increase in asset prices. Borrowers start to sell off their assets. During an economic downturn, the demand for credit decreases as the investors’ expectations of the future become more pessimistic. This causes both borrowers and lenders to proceed with greater caution (Kindleberger & Aliber 2005). Consequently, financial fragility might arise and an economy moves from ‘hedge finance’ through ‘speculative finance’ and finally ends with ‘Ponzi finance’ (Minsky 1986).

Further disruptions might emerge from changes in the distribution of income. In Post Keynesian models of distribution and growth, the redistribution between wages and profits feeds back on consumption demand, given different propensities to save from rentiers’, managers’, and workers’ income, thereby, affecting overall aggregate demand and growth (Hein 2010; Hein & van Treeck 2010a, b; Onaran et al. 2011). However, redistribution also impacts on firms’ investment through different channels, either directly or indirectly via profits or capacity utilization. Based on these contradictory effects of redistribution between capital and labor, Bhaduri & Marglin (1990) argue that aggregate demand and long-run growth may either be ‘wage-led’ or ‘profit-led.’ In recent years, multiple studies based on this framework show that in the medium-to long-term, demand in most OECD countries seems to be wage-led (see, for example, Naastepad & Storm 2007; Hein & Vogel 2008). Therefore, a decline in labor’s income share partially causes a reduction in aggregate demand and growth.

Like Marxian theories delineated above, a view that capitalist development is divided into historical stages is inherent to the Post Keynesian approach. The most recent phase of capitalism is often referred to as ‘finance-dominated’ or ‘money manager’ capitalism. In this framework, financialization is defined as a combination of three phenomena: a rise in shareholder value orientation of the firm, redistribution of income and wealth in favor of shareholders and managers at the expense of ordinary workers and employees, and more opportunities for debt-financed consumption (van Treeck 2012).

On theoretical grounds, it is argued that financialization might impact investment, consumption, and distribution. With regard to firms’ investment in capital stock, it is argued that an increase in shareholder value orientation might have two effects on the management. First, given shareholders’ increasing demand for higher dividends, internal funds necessary for investment purposes decline. Moreover, investment is increasingly financed through debt, leading to rising obligations in interest payments.8 Second, the alignment of shareholders’ and managers’ interests through variable remuneration in the form of stock options changes managerial preferences from high growth rates to high short-term profitability. Thereby, financialization depresses management’s animal spirits (Hein 2010). In regard to consumption, financialization has opened up the possibilities for consumption based on the wealth effect and financed by debt. Finally, it is argued that financialization impacts on the distribution of income. Regarding functional income distribution, it is argued that at least in the medium-term, shareholders’ rising demand for dividend payouts come at the expense of the share of wages in national income. This notion is based on Kalecki’s mark-up pricing theory, which assumes that in the medium-term the markup is dividend-elastic. Hence firms are able to increase dividend payments, which constitute an increase in overhead costs and in the mark-up (Hein 2014).

With regard to investment, empirical evidence lends support to the hypothesis that financialization has indeed contributed to a slowdown in accumulation through the ‘preference channel’ and ‘internal means of finance channel.’ Firms that pursue short-term profits substitute financial investment for real investment in capital stock (Stockhammer 2004; Orhangazi 2008). Moreover, real investment is also dampened by a rise in interest and dividend payments (Orhangazi 2008; van Treeck 2008). However, the negative impact of financialization on real investment seems to concern larger firms rather than small firms (Davis 2013).

Empirical studies also show that the ‘wealth effect’ of either stock market or housing price changes substantially alters consumer spending (Slacalek 2009; Sousa 2009). However, regional differences exist. The wealth effect from changing house prices appears to be more relevant in Anglo-Saxon countries compared to countries like France, Germany, Spain, and Japan (Girouard et al. 2006).

There seems to be a consensus in the literature that rising household indebtedness is related to income inequality (Kumhof & Ranciere 2010; Rajan 2010). In times of stagnating or declining incomes, households increasingly go into debt to maintain their standard of living (Goldstein 2012) and to finance conspicuous consumption in order to ‘keep up with the Joneses’ (Frank 2007). At the same time, households took advantage of new financial opportunities to finance consumption. It is argued that the rise in borrowing reflects a broader transformation in household behavior towards more risk taking. Empirical evidence suggests that household indebtedness and the use of financial products has risen among all income recipients (Fligstein & Goldstein 2015).

Empirical studies suggest that financialization also has an impact upon income distribution. First, in most OECD countries, financialization favors property owners, which is measured by a rise in rentiers’ income shares (Power et al. 2003; Epstein & Jayadev 2005; Dünhaupt 2012). Moreover, it appears that financialization has also contributed to the decline in labor’s share of income (Lin & Tomaskovic-Devey 2013; Köhler et al. 2015; Stockhammer 2015a; Dünhaupt 2017) and to the rise in personal income inequality (Kus 2012; Dünhaupt 2014).

Post Keynesians have incorporated elements of financialization into macroeconomic models of distribution and growth. The crux of their analysis is the development of functional income distribution and the responsiveness of consumption out of labor and rentier income, and the investment activity of corporations.9 According to Post Keynesian theory, different growth regimes can emerge under financialization with more or less favorable outcomes (Boyer 2000; Hein 2012). In a ‘finance-led growth’ regime, the spread of the shareholder value doctrine has a positive effect on growth—although redistribution from labor to rentier income takes place, consumption remains strong due to a high propensity to consume out of rentiers’ income and due to debt-financed consumption related to a strong wealth effect. Moreover, investment is stimulated via the accelerator mechanism. The second growth regime is called ‘profits without investment’ that resembles the first regime with the only difference being that there is no stimulation of investment. The third growth regime is called the ‘contractive’ regime. As the name suggests, the rise in firms’ payout ratio has a negative effect on capacity utilization, profit, and capital accumulation. Moreover, consumption remains low in this regime (Hein 2014).

Empirical studies suggest that before the 2007 crisis many OECD countries pursued a ‘profits without investment’ regime, which is characterized by rising levels of profits in spite of weak real investment (van Treeck et al. 2007; van Treeck & Sturn 2012; Hein & Mundt 2012; Hein 2014). From a macroeconomic perspective, a ‘profits without investment’ regime is only possible if demand is generated by another component—that is, consumption, government deficits, or export surpluses. This becomes apparent from Kalecki’s (1965: 49) famous profit equation:

Gross profits net of taxes = Gross investment + Export surplus + Budget deficit – Workers’ saving + Capitalists’ consumption

Since the early 1980s in the US GDP growth has been mainly driven by private consumption, whereas investment in capital stock has increased rather moderately, except during the New Economy boom in the late 1990s. Hence, until the Great Recession, US growth relied mainly on debt-led consumption, expansionary fiscal policy, and capital imports. According to Palley (2009), Minsky’s financial instability hypothesis can be considered an explanation as to why the US economy did not end up in stagnation much earlier: the tremendous rise in borrowing was enabled by financial innovation and deregulation, which increased financial fragility.

However, the debt-led consumption boom growth model was practiced by not only the US but also other countries, such as the UK, Spain, Ireland, and Greece. Falling labor income shares and low investment in capital stock are associated with another growth model, ‘exportled mercantilist,’ which emerged in other countries. Countries that relied on this growth model experienced only weak domestic demand and were strongly dependent on international trade, running current account surpluses. Here, Japan and Germany are prominent examples (Hein 2012).10

Both growth models contributed to the rise in global imbalances until the beginning of the Great Recession in 2008–09. Enabled by the liberalization of international capital markets and the removal of capital controls, countries that pursue the ‘debt-led consumption boom’ strategy depend, on the one hand, on global markets’ credit supply resulting in current account deficits. On the other hand, those countries also depend on domestic demand through borrowing by households against rising house and asset prices. ‘Export-led mercantilist’ countries, however, run current account surpluses and depend strongly on global demand.

Many Post Keynesians argue that in light of falling labor shares and rising income inequality, financialization fostered the emergence of these highly fragile growth regimes through its effects on investment and consumption (see, for example, Hein 2012; Hein & Mundt 2012; van Treeck & Sturn 2012; Stockhammer 2013). The world economic and financial crisis that started in the US in 2007 has undermined the sustainability of both systems. Apparently, the debt-led consumption boom came to a halt, as household indebtedness became unsustainable. On the flipside, export-mercantilist countries were affected as well, given the decline in global demand and the devaluation of their capital exports (Hein 2014).

The topic of financialization encompasses many themes and can be addressed from a number of angles. The purpose of this chapter has been to review and introduce the literature focusing on financialization as the latest stage of capitalism. All heterodox approaches considered here agree that since the late 1970s or early 1980s capitalism has entered a new stage—‘global neoliberalism,’ ‘monopoly finance capitalism,’ or ‘finance-led capitalism.’ It is apparent that each heterodox approach has a special focus of attention.

The basic narrative in all approaches draws on the same elements. First, in the era of neoliberalism and financialization, wages stagnate and income is redistributed from labor to capital. However, the rise in income inequality does not lead to a decline in consumption demand and a crisis of under-consumption. Second, consumption demand is debt-financed along with asset price inflation. At the same time, the financial sector is liberalized and deregulated and financial speculation increases.

While the basic narrative is quite similar, major differences stem from both the relationship between neoliberalism and financialization and the question of whether financialization can be considered as a cause or effect.

Proponents of the SSA theory argue that neoliberalism is the main characteristic of the recent phase of capitalism. According to this view, neoliberalism fosters the emergence of inequality, the shift in financial practices, and asset bubbles. While a crisis of under-consumption could be avoided by the rise of debt-financed consumption, a crisis of over-accumulation of fixed capital emerges. The latter can be considered as a crisis of capitalism in general. Furthermore, it is argued that “financialization is an ever-present tendency in corporate capitalism and, once neoliberalism released the constraints against it, it developed rapidly in the favorable neoliberal institutional context” (Kotz 2011: 15). Even though neoliberalism is identified as the root problem which allowed financialization to appear and which furthered a structural crisis of capitalism, it is argued that a reversal towards a more social-democratic form of capitalism is insufficient, since it is capitalism as an economic system per se that is inherently unstable.

The position of the Monthly Review school is reminiscent of the position taken by SSA theory in the sense that the contradictions of capitalism are considered the main problem. In the era of monopoly-finance capitalism, the high degree of monopolization and industrial maturity result in deep-seated stagnation tendencies. Consumption and investment are not sufficient to absorb the high surpluses that are generated. These surpluses are channeled into debt-leveraged speculation. It is argued that capitalist economies are trapped in a circle of stagnation and financialization. In contrast to proponents of the SSA School, the Monthly Review school argues that it is financialization that leads to neoliberalism. Financialization is a response to a stagnation-prone economy, while neoliberalism is the ideological counterpart of monopoly-finance capitalism. More importantly, there is no cure to the system, since “the fault is in the system” (Foster & McChesney 2010).

For Post Keynesians, financialization and neoliberalism are two complementary concepts. According to Palley (2013: 1),

financialization corresponds to financial neoliberalism which is characterized by domination of the macro economy and economic policy by financial sector interests. According to this definition, financialization is a particular form of neoliberalism. That means neoliberalism is the driving force behind financialization and the latter cannot be understood without an understanding of the former.

In this view, the rise of finance emanates from the deregulation and liberalization of the financial (and economic) system. That is to say, financialization is the cause rather than the effect. Financialization affects the macroeconomy via four channels—income distribution, investment in capital stock, household debt, and net exports and current account balances. In light of falling labor income shares and depressed investment in capital stock, Post Keynesians argue that ‘profits without investment’ regimes emerged, which are either driven by debt-led consumption or rising export surpluses. Both regimes, however, are prone to crisis. As a remedy, it is argued that economic structures dominated by financialization should be addressed on four dimensions: re-regulation and downsizing of the financial sector, redistribution of income from top to bottom and from capital to labor, re-orientation of macroeconomic policies towards stabilizing domestic demand at non-inflationary full employment levels, and re-creation of international monetary and economic policy coordination.11

1 As highlighted by Albritton (1986), there are many more categorizations of capitalist history; for example, the classification into competitive and monopoly capitalism or laissez-faire, monopoly, and state monopoly capitalism.

2 For an excellent review of the French Régulation, Social Structure of Accumulation, and Post Keynesian approaches, see Hein et al. (2015). See also Lapavitsas (2011, 2013) for a review of economic and sociological literature on financialization and his own analysis of financialization, which draws on classical Marxism.

3 BEA NIPA Table 6.16. Available at http://www.bea.gov/national/nipaweb/DownSS2.asp. See also Crotty (2007).

4 See FESSUD Studies in Financial Systems. http://fessud.eu/studies-in-financial-systems/

5 Part of this rise can be attributed to the increase in financial innovation and the introduction of new financial instruments (see Grabel 1997).

6 The regulated capitalist SSA, which is also called ‘post-war SSA,’ lasted from the end of World War II until the late 1970s. Many authors (Gordon et al. 1987; Wolfson & Kotz 2010) argue that the crisis of the post-war SSA was one of profit squeeze, brought about by a relative rise in labor’s power and rising real wages.

7 Economic surplus is defined as the difference between “what a society produces and the costs of producing it” (Baran & Sweezy 1966: 9).

8 This theoretical claim is called into question by recent research. See, for example, Jo (2015) and Kliman & Williams (2015).

9 Certainly, financialization might also impact on aggregate demand and growth via its direct effects on consumption and investment behavior. Further influences are related to macroeconomic policies, government demand management, and the overall macroeconomic policy regime (see Hein & Mundt 2012).

10 A very good overview and a range of specific country studies on this topic are provided by Hein et al. (2016).

11 Compare Hein (2016) and the literature quoted in the document.

Albritton, R. 1986. ‘Stages of capitalist development.’ Studies in Political Economy, 19 (Spring): 113–139.

Arestis, P. 1996. ‘Post-Keynesian economics: towards coherence.’ Cambridge Journal of Economics, 20 (1): 111–135.

Baran, P. & Sweezy, P. 1966. Monopoly Capital. New York: Monthly Review Press.

Beck, T., Demirgüç-Kunt, A., & Levine, R. 2000. ‘A new database on financial development and structure.’ World Bank Economic Review, 14 (3): 597–605.

Bhaduri, A. & Marglin, S. 1990. ‘Unemployment and the real wage: the economic basis for contesting political ideologies.’ Cambridge Journal of Economics, 14 (4): 375–393.

Boyer, R. 2000. ‘Is a finance-led growth regime a viable alternative to Fordism? A preliminary analysis.’ Economy and Society, 29 (1): 111–145.

Clarke, S. 1994. Marx’s Theory of Crisis. Basingstoke, UK: Macmillan Press.

Crotty, J. 1986. ‘Marx, Keynes and Minsky on the instability of the capitalist growth process and the nature of government economic policy,’ in: D. Bramhall & S. Helburn (eds.), Marx, Keynes and Schumpeter: A Centenary Celebration of Dissent. Armonk, NY: M.E Sharpe, 297–326.

Crotty, J. 2007. If financial market competition is so intense, why are financial firm profits so high? Reflections on the current ‘golden age’ of finance. PERI Working Paper No. 134.

Davis, L. 2013. Financialization and the nonfinancial corporation: an investigation of firm-level investment behavior in the U.S., 1971–2011. University of Massachusetts Amherst Working Paper 2013–08.

Detzer, D., Dodig, N., Evans, T., Hein, E., & Herr, H. 2013. The German financial system. FESSUD Studies in Financial Systems No. 3.

Dünhaupt, P. 2012. ‘Financialization and the rentier income share-evidence from the USA and Germany.’ International Review of Applied Economics, 26 (4): 465–487.

Dünhaupt, P. 2014. An empirical assessment of the contribution of financialization and corporate governance to the rise in income inequality. IPE Working Paper 41/2014.

Dünhaupt, P. 2017. ‘Determinants of labor’s income share in the era of financialisation.’ Cambridge Journal of Economics, 41 (1): 283–306.

Dore, R. 2008. ‘Financialization of the global economy.’ Industrial and Corporate Change, 17 (6): 1097–1112.

ECB. 2007. ‘Share buybacks in the Euro area.’ European Central Bank Monthly Bulletin, May: 103–111.

ECB. 2012. ‘Corporate indebtedness in the euro area.’ European Central Bank Monthly Bulletin, February: 87–103.

Epstein, G. (ed.) 2005. Financialization and the World Economy. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

Epstein, G. 2015. Financialization: there’s something happening here. PERI Working Paper No. 394.

Epstein, G. & Jayadev, A. 2005. ‘The rise of rentier incomes in OECD countries: Financialization, central bank policy and labor solidarity,’ in: G. Epstein (ed.), Financialization and the World Economy. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar, 46–74.

Evans, T. 2004. ‘Marxian and post-Keynesian theories of finance and the business cycle.’ Capital & Class, 28 (2): 47–100.

Ferrari-Filho, F. & Camargo Conseicao, O.A. 2005. ‘The concept of uncertainty in Post Keynesian theory and in institutional economics.’ Journal of Economic Issues, 39 (3): 579–594.

Fligstein, N. & Goldstein, A. 2015. ‘The emergence of a finance culture in American households, 1989–2007.’ Socio-Economic Review, 13 (3): 575–601.

Foley, D. & Duménil, G. 2008. ‘Marxian transformation problem,’ in: S.N. Durlauf & L.E. Blume (eds.), The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics, 2nd online edn. Palgrave Macmillan.

Foster, J.B. 2006. ‘Monopoly-finance capital.’ Monthly Review, 58 (7). Available from http://monthlyreview. org/2006/12/01/monopoly-finance-capital [Accessed April 26, 2016]

Foster, J.B. 2007. ‘The financialization of capitalism.’ Monthly Review, 58 (11). Available from http://monthlyreview.org/2007/04/01/the-financialization-of-capitalism/ [Accessed April 26, 2016]

Foster, J.B. 2008. ‘The financialization of capital and the crisis.’ Monthly Review, 59 (11). Available fromhttp://monthlyreview.org/2008/04/01/the-financialization-of-capital-and-the-crisis [Accessed April 26, 2016]

Foster, J.B. 2010a. ‘The age of monopoly-finance capital.’ Monthly Review, 61 (9). Available from http://monthlyreview.org/2010/02/01/the-age-of-monopoly-finance-capital [Accessed April 26, 2016]

Foster, J.B. 2010b. ‘The financialization of accumulation.’ Monthly Review, 62 (5). Available from http://monthlyreview.org/2010/10/01/the-financialization-of-accumulation [Accessed April 26, 2016]

Foster, J.B. & McChesney, R.W. 2009. ‘Monopoly-finance capital and the paradox of accumulation.’ Monthly Review, 61 (5). Available from http://monthlyreview.org/2009/10/01/monopoly-finance-capital-and-the-paradox-of-accumulation [Accessed April 26, 2016]

Foster, J.B. & McChesney, R.W. 2010. ‘Listen Keynesians, it’s the system! Response to Palley.’ Monthly Review, 61 (11). Available from https://monthlyreview.org/2010/04/01/listen-keynesians-its-the-system-response-to-palley/ [Accessed April 26, 2016]

Frank, R. 2007. Falling Behind: How Rising Inequality Harms the Middle Class. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Girouard, N., Kennedy, M., van den Noord, P., & André, C. 2006. Recent house price developments: the role of fundamentals. OECD Economics Department Working Paper, No. 475.

Goda, T. 2013. The role of income inequality in crisis theories and in the subprime crisis. Post Keynesian Economics Study Group Working Paper 1305.

Goldstein, A. 2012. Income, consumption, and household indebtedness in the U.S., 1989–2007. Department of Sociology, University of California. Unpublished Manuscript.

Gordon, D., Weisskopf, T., & Bowles, S. 1987. ‘Power, accumulation and crisis: the rise and demise of the postwar social structure of accumulation,’ in: R. Cherry, C. D’Onofrio, C. Kurdas, T. Michl, F. Moseley, & M.I. Naples (eds.), The Imperiled Economy: Book I: Macroeconomics from a Left Perspective. New York: Union for Radical Political Economics, 43–58.

Grabel, I. 1997. ‘Savings, investment, and functional efficiency: a comparative examination of national financial complexes,’ in: R. Pollin (ed.), The Macroeconomics of Saving, Finance and Investment. Ann Arbor, MI: The University of Michigan Press, 251–297.

Greenwood, R. & Scharfstein, D. 2013. ‘The growth of finance.’ Journal of Economic Perspectives, 27 (2): 3–28.

Hein, E. 2010. ‘Shareholder value orientation, distribution and growth: short- and medium-run effects in a Kaleckian model.’ Metroeconomica, 61 (2): 302–332.

Hein, E. 2012. The Macroeconomics of Finance-Dominated Capitalism – And Its Crisis. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

Hein, E. 2014. Distribution and Growth after Keynes: A Post-Keynesian Guide. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

Hein, E. 2016. Causes and consequences of the financial crisis and the implications for a more resilient financial and economic system. IPE Working Paper 61/2016.

Hein, E. & Mundt, M. 2012. Financialisation and the requirements and potentials for wage-led recovery: a review focusing on the G20. Conditions of Work and Employment Series No. 37, International Labour Organisation.

Hein, E. & van Treeck, T. 2010a. ‘‘Financialisation’ in post-Keynesian models of distribution and growth: a systematic review,’ in: M. Setterfield (ed.), Handbook of Alternative Theories of Economic Growth. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar, 277–292.

Hein, E. & van Treeck, T. 2010b. ‘‘Financialisation’ and rising shareholder power in Kaleckian/post-Kaleckian models of distribution and growth.’ Review of Political Economy, 22 (2): 205–233.

Hein, E. & Vogel, L. 2008. ‘Distribution and growth reconsidered: empirical results for six OECD countries.’ Cambridge Journal of Economics, 32 (3): 479–511.

Hein, E., Detzer, D., & Dodig, N. (eds.) 2016. Financialization and the Financial and Economic Crisis: Country Studies. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

Hein, E., Dodig, N., & Budyldina, N. 2015. ‘The transition towards finance-dominated capitalism: French Regulation School, Social Structures of Accumulation and post-Keynesian approaches compared,’ in: E. Hein, D. Detzer, & N. Dodig (eds.), The Demise of Finance-dominated Capitalism: Explaining the Financial and Economic Crises. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar, 7–53.

Jo, T.-H. 2015. ‘Financing investment under fundamental uncertainty and instability: a heterodox microeconomic view.’ Bulletin of Political Economy, 9 (1): 33–54.

Kalecki, M. 1965. Theory of Economic Dynamics, 2nd edn. London: George Allen and Unwin.

Kenway, P. 1983. ‘Marx, Keynes and the possibility of crisis,’ in: J. Eatwell & M. Milgate (eds.), Keynes’s Economics and the Theory of Value and Distribution. New York: Oxford University Press, 149–166.

Kindleberger, C & Aliber, R. 2005. Maniacs, Panics, and Crashes. A History of Financial Crises, 5th edn. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Kliman, A. & Williams, S.D. 2015. ‘Why ‘financialization’ hasn’t depressed US productive investment.’ Cambridge Journal of Economics, 39 (1): 67–92.

Köhler, K., Guschanski, A., & Stockhammer, E. 2015. How does financialization affect functional income distribution? A theoretical clarification and empirical assessment. Kingston University Economics Discussion Paper 2015–5.

Kotz, D. 2008. ‘Contradictions of economic growth in the neoliberal era: accumulation and crisis in the contemporary U.S. economy.’ Review of Radical Political Economics, 40 (2): 174–188.

Kotz, D. 2009. ‘The financial and economic crisis of 2008: a systemic crisis of neoliberal capitalism.’ Review of Radical Political Economics, 41 (3): 305–317.

Kotz, D. 2011. ‘Financialization and neoliberalism,’ in: G. Teeple & S. McBride (eds.), Relations of Global Power: Neoliberal Order and Disorder. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Kotz, D. 2012. Social structures of accumulation, the rate of profit, and economic crises. PERI Working Paper No. 329. University of Massachusetts Amherst.

Kotz, D. 2013. ‘The current economic crisis in the U.S.: a crisis of over-investment.’ Review of Radical Political Economics, 45 (3) 284–294.

Kotz, D. & McDonough, T. 2010. ‘Global neoliberalism and the contemporary social structure of accumulation,’ in: T. McDonough, M. Reich, & D. Kotz (eds.), Contemporary Capitalism and its Crises: Social Structure of Accumulation Theory for the 21st Century. New York: Cambridge University Press, 93–120.

Kriesler, P. 2013. ‘Post-Keynesian perspectives on economic development and growth,’ in: G.C. Harcourt & P. Kriesler (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Post-Keynesian Economics, Volume 1: Theory and Origins. New York: Oxford University Press, 539–555.

Kumhof, M. & Ranciere, R. 2010. Inequality, leverage and crises. IMF Working Paper 10/268.

Kus, B. 2012. ‘Financialisation and income inequality in OECD nations: 1995–2007.’ The Economic and Social Review, 43 (4): 477–495.

Lapavitsas, C. 2011. ‘Theorizing financialization.’ Work, Employment and Society, 25 (4): 611–626.

Lapavitsas, C. 2013. ‘The financialization of capitalism: ‘profits without producing’.’ City: Analysis of Urban Trends, Culture, Theory, Policy, Action, 17 (6): 792–805.

Lazonick, W. 2010. ‘The explosion of executive pay and the erosion of American prosperity.’ Entreprises et Histoire, 57: 141–164.

Lazonick, W. 2011. The innovative enterprise and the developmental state: toward an economics of ‘organizational success.’ Paper presented at the conference of the Institute for New Economic Thinking, Bretton Woods, NH, April 10.

Lazonick, W. & O’Sullivan, M. 2000. ‘Maximizing shareholder value: a new ideology for corporate governance.’ Economy and Society, 29 (1): 13–35.

Lin, K.-H. & Tomaskovic-Devey, D. 2013. ‘Financialization and US income inequality 1970–2008.’ American Journal of Sociology, 118 (5): 1284–1329.

Lippit, V. 2010. ‘Social structure of accumulation theory,’ in: T. McDonough, M. Reich, & D. Kotz, (eds.), Contemporary Capitalism and its Crises: Social Structure of Accumulation Theory for the 21st Century. New York: Cambridge University Press, 45–71.

Magdoff, H. & Sweezy, P.M. 1987. Stagnation and the Financial Explosion. New York: Monthly Review Press.

Marx, K. 1887. Capital: A Critique of Political Economy, Volume 1. Moscow: Progress Publisher.

McDonough, T., Reich, M., & Kotz, D. 2010. ‘Introduction: social structure of accumulation theory for the 21st Century,’ in: T. McDonough, M. Reich, & D. Kotz (eds.), Contemporary Capitalism and its Crises: Social Structure of Accumulation Theory for the 21st Century. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1–8.

Minsky, H. 1986. Stabilizing an Unstable Economy. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Naastepad, C.W.M. & Storm, S. 2007. ‘OECD demand regimes (1960–2000).’ Journal of Post Keynesian Economics, 29 (2): 211–246.

OECD. 2015. Financial indicators. Available from https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=FIN_IND_FBS [Accessed April 26, 2016]

OECD. 2014. ‘Household debt,’ in: Nationals Accounts at a Glance 2014. Paris: OECD Publishing, 80–81.

Onaran, Ö., Stockhammer, E., & Grafl, L. 2011. ‘Financialization, distribution, and aggregate demand in the US.’ Cambridge Journal of Economics, 35 (4): 637–662.

Orhangazi, Ö. 2008. ‘Financialisation and capital accumulation in the non-financial corporate sector: a theoretical and empirical investigation on the US economy: 1973–2003.’ Cambridge Journal of Economics, 32 (6): 863–886.

Palley, T. 2009. The limits of Minsky’s financial instability hypothesis as an explanation of the crisis. IMK Working Paper 11/2009.

Palley, T. 2013. Financialization: The Economics of Finance Capital Domination. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Philippon, T. & Reshel, A. 2013. ‘An international look at the growth of modern finance.’ Journal of Economic Perspectives, 27 (2): 73−96.

Power, D., Epstein, G., & Abrena, M. 2003. Trends in rentier incomes in OECD countries. 1960–2000. PERI Working Paper No. 58a.

Rajan, R. 2010. Fault Lines: How Hidden Fractures Still Threaten The World Economy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Slacalek, J. 2009. What drives personal consumption? The role of housing and financial wealth. ECB Working Paper, No. 1117.

Steindl, J. [1952] 1976. Maturity and Stagnation. New York: Monthly Review Press.

Sousa, R. 2009. Wealth effects on consumption: evidence from the Euro area. ECB Working Paper, No. 1050.

Stockhammer, E. 2004. ‘Financialisation and the slowdown of accumulation.’ Cambridge Journal of Economics, 28 (5): 719–741.

Stockhammer, E. 2013. ‘Financialization and the global economy,’ in: M. Wolfson & G. Epstein (eds.), The Handbook of the Political Economy of Financial Crises. New York: Oxford University Press, 512–525.

Stockhammer, E. 2015a. ‘Determinants of the wage share: a panel analysis of advanced and developing countries.’ British Journal of Industrial Relations. doi: 10.1111/bjir.12165.

Stockhammer, E. 2015b. Neoliberal growth models, monetary union and the Euro crisis: a Post-Keynesian perspective. Post Keynesian Economics Study Group Working Paper 1510.

van Treeck, T. 2008. ‘Reconsidering the investment-profit nexus in finance-led economies: an ARDL-based approach.’ Metroeconomica, 59 (3): 371–404.

van Treeck, T. 2012. ‘Financialization,’ in: J. King (ed.), The Elgar Companion to Post Keynesian Economics, 2nd edn. Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar.

van Treeck, T. & Sturn, S. 2012. Income inequality as a cause of the great recession? A survey of current debates. Conditions of Work and Employment Series No. 39, International Labour Organisation.

van Treeck, T., Hein, E., & Dünhaupt. P. 2007. Finanzsystem und wirtschaftliche Entwicklung, neuere Tendenzen in den USA und in Deutschland. IMK Studies 5/2007.

Wallerstein, I. 1974. ‘The rise and future demise of the world capitalist system: concepts for comparative analysis.’ Comparative Studies in Society and History, 16 (4): 387–415.

Weisskopf, T. 1992. ‘Marxian crisis theory and the contradictions of late twentieth-century capitalism.’ Rethinking Marxism, 4 (4): 368–391.

Wolfson, M & Kotz, D. 2010. ‘A reconceptualization of social structure of accumulation theory,’ in: T. McDonough, M. Reich, & D. Kotz (eds.), Contemporary Capitalism and its Crises—Social Structure of Accumulation Theory for the 21st Century. New York: Cambridge University Press, 72–90.